2.1. The SSL Teachers’ Scaffolding of Advanced Content

In our fieldwork, we collected fieldnotes from the SSL classes of three teachers (Sandra at Pine, Stephen at Rowan, and Wera at Birch) and audio-recordings of interviews during the course of more than 1.5 years (in total, 58 lessons, with 20–25 students for each lesson). In these three schools, a majority of the students studied SSL; thus, SSL was not an exception. Of the 15 students who were interviewed, several chose to do so in pairs or triads; each interview lasted approximately one hour. A majority of the students (10) had arrived in Sweden during middle or secondary school, and five were born in Sweden. Both researchers conducted the interviews in a separate room at the schools. The teachers were interviewed individually by both researchers.

In one paper, we focused specifically on the students (

Hedman and Magnusson 2020a), as learner perspectives in SSL are largely lacking (see, however,

Bjuhr 2019;

Siekkinen 2021). We conducted the student interviews with individuals or as pairs or groups with 15 students in SSL in their final or penultimate year of upper secondary school. Our main inquiry was both why the students had chosen SSL, as opposed to the more prestigious subject Swedish, and why they had continued to study SSL throughout upper secondary. We found this to be of interest since (1) the students are entitled to make these choices themselves at the upper secondary school level, as opposed to the compulsory school where the school decides on this matter, and (2) there are reasons to gain insight into why students choose SSL over SWE, considering the possible stigmatization of studying SSL, a subject of lower prestige (

Fridlund 2011;

Torpsten 2008).

A prominent reason for choosing SSL was the opportunities afforded for extensive pedagogical scaffolding of advanced academic content (

Hedman and Magnusson 2020a). To situate SSL in an international context, we believe it to be important to point out that the teaching was directed toward meaningful language use in writing, classroom interaction and the reading of fiction and factual texts, as opposed to decontextualized basic reading and writing. In Sandra’s SSL course, in the final year of upper secondary school, we followed a theme on social class. A focus was on the teaching of the expository genre, one of the genres addressed in the SWE and SSL syllabi. For this theme, a short text on Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of capital was central, exploring the idea of cultural rather than economic capital. They also read two articles illustrating the theoretical concepts: the first by a journalist describing her experiences as a working-class child entering a new world as an art student, and the second by the football player Zlatan Ibrahimović, rendering his experiences of growing up in a low-status neighborhood in Malmö.

Excerpt 1 exemplifies how Sandra strived to scaffold a girl in the final year of upper secondary school to make a stronger case through coherent argumentation (see

Appendix A for original transcripts in Swedish). The excerpt also illustrates how Sandra’s feedback moved between the academic content, the textual level and individual wordings, including grammar. The excerpt begins in the midst of a discussion on the economic and cultural side to the notion of capital.

| Excerpt 1. Fieldnotes from Pine (15 March 2017). |

| Sandra: | Here you have mixed it up a bit I think. First you’re supposed to give an example of her discovering class, which was when she attended an art school. And then we wonder what happened there? We want examples. What happened, what did she experience? Because now we’ve got an introduction, what’s the difference? It’s not only about economy. |

| Student: | Knowledge. |

| Sandra: | Yeah, and the right kind of knowledge. There are examples in the text. But she also tells us that in some other context when she was in a store, then she felt more prosperous, the others read about love, she read art magazines. So, here we want to look at examples, show the differences (WRITES). Show the difference between the art school and the extra job… have you experienced that… if your family thinks you’re good at football but if you get somewhere else perhaps football is not considered important. Have you experienced that? |

| Student: | No but I understand. |

| Sandra: | Perhaps you’re good at computing. |

| Student: | I’m good at body building. |

| Sandra: | Yes and if you’re somewhere where exercise is important you’ll have status but here perhaps no one cares, there’s different status in different contexts. |

| Student: | Mm /…/ |

| Sandra: | And then you don’t gather it here. And then I’m thinking about the wording and tense. The tense of the verb. “He doesn’t buy that now” how do you decline that? |

| Student: | bought. |

| Sandra: | Yes… and still, here you’re influenced by English, “spend time”, “spend” (Sw. SPENDERA) is for money but for time I think you should say “spend” (Sw. TILLBRINGA) … “He feels a bit funny”, what do you mean… That it was fun? Look what’s in the text… OK. |

In their explorations of capital and social class, Sandra and the student acknowledge that what is considered valuable knowledge differs between contexts. This is exemplified both in one of the articles and the student’s own experiences (such as the value of being good at body building). The excerpt illustrates Sandra’s recurring efforts to anchor the idea of social class and cultural capital in the students’ realities. The excerpt also includes a correction of grammar and expansion of lexical knowledge, when Sandra asks for the idiomatic morphology of köpa (‘buy’) in the past tense, as well as remarks on the choice of verb for “spending time” in Swedish, suggesting tillbringa instead of spendera. Sandra’s scaffolding was built on her knowledge of the needs of each student, and the level of handover of responsibility to the students thus varied. In the case illustrated in excerpt 1, the handover is not very prominent.

The students participating in the interviews expressed, in particular, an appreciation of their teachers’ interactive scaffolding, and they explained in various ways what constituted this support. For example, the SSL teacher was found to be more student oriented and tended not to leave the students until it was clear that they understood the task: “so everybody understands, that’s guaranteed”, as expressed by one student in Sandra’s class (

Hedman and Magnusson 2020a, p. 9). The SSL teacher’s meaning-making is further illustrated in an incidence at Rowan (building on an extended memo from fieldnotes, 12 December 2016, cf.

Emerson 2004), where all final year students were summoned by the “first teacher” in Swedish for a lecture on how the upcoming National Tests in Swedish should be assessed by the teachers. We noted how the SSL teacher Stephen, who was also present, was called upon by the students to clarify details. From the reactions of the students, he seemed to convey and elaborate on this information in comprehensible ways. We find this to be indicative of a broader pattern in our data, regarding the SSL teachers’ “explanatory force”.

Stephen’s pedagogical scaffolding was further evident in analyses of audio-recorded examining literary talks on the ancient novel

The tale of a manor by Selma

Lagerlöf (

1899), through the use of a graphic novel (

Ivarsson 2013). These dialogues were characterized by verbal elaborations instigated by Stephen and reflected the significance of using multimodal resources as a means for making meaning of advanced texts. A focus on meaningful language use, in tandem with advanced content, was thus evident also in the reading of literary texts. In excerpt 2, Zara, from Birch, describes how interaction with her teacher Wera resulted in an understanding of the novel

One Eye Red by Jonas Hassen Khemiri (

Khemiri 2003; see

Hedman and Magnusson 2020a, p. 8).

| Excerpt 2. Interview with student Zara at Pine. |

| Zara: | Um in Swedish, don’t know, well the teachers expected us to know what is written, and I had difficulties with reading comprehension and still it like didn’t help, we were expected to know it all but, now since I came to Wera [the SSL teacher], she said, then she went through like even more in detail and it got much clearer so now I understand things better. For example, we read this “An Eye Red” and um we read the book, Wera had already read it before I think. So when we didn’t understand things we went to her, so she said “well yes he says this and that, what do you think he says, he said this before”, um tried to connect them like that and so, she used to give us clues, how clues, how we can understand the text. |

| Researcher: | Does it work? |

| Zara: | Yes it worked very well, I understood, it was the first book that I understood fully [laughter] yes well I usually understand when I read books too. (Hedman and Magnusson 2020a, p. 8) |

Excerpt 2 reflects the fact that students do not get enough support in the classroom to negotiate and understand literary texts. To Zara, this was a new experience in Wera’s SSL classroom.

In sum, the insights outlined so far highlight the teaching of both language and literature, and also show that extensive pedagogical scaffolding can make literature accessible without using simple texts. This pedagogical scaffolding was also reflected in the students’ portrayals of SSL as a space that afforded them opportunities to understand advanced literacy and academic content, as well as literature (

Hedman and Magnusson 2020a). These positive evaluations could further be understood in relation to the local status of the SSL teachers at the schools. Both Sandra and Stephen were also teachers of SWE, and

förstelärare4 (

first teacher, see above) of SSL. Their expertise on teaching and assessing second language development was thus formally recognized among colleagues, and they both found SSL to have a high prestige locally. We found the teachers’ expertise to be frequently called for by teachers of other subjects (

Hedman and Magnusson 2020b). These findings differ from those realized in other second language learning contexts, such as Steven Talmy’s fieldwork on ESL for recently arrived students in Hawaii (e.g.,

Talmy 2015). They were subjected to undemanding and age-inappropriate content outside of the curriculum taught by unqualified teachers and were, in addition, addressed in pejorative terms (see also

Hedman and Magnusson 2020a, p. 3).

2.2. The Role of Curricular Multilingual Aspects in SSL

The subject contributes to strengthening students’ multilingualism and confidence in their own language ability […] The students shall also be given the opportunity to reflect on their multilingualism and their prerequisites to conquer and develop a functional and rich second language in Swedish society. […] Multilingualism is an asset for the individual as well as for society, and by comparing language knowledge and language experiences with others the students shall be given the opportunity to develop a better understanding of what function language has for communication, thinking and learning.

Some students referred to these goals as a primary reason for studying SSL, as evident in excerpt 3 (see

Hedman and Magnusson 2019, pp. 10–11).

| Excerpt 3. Interview with student Fjodar at Birch. |

| Researcher: | And then we wonder why you chose Swedish as a second language? |

| Fjodar: | Ehm, well, Swedish as a second language and Swedish as a first language do differ to large extents, and in SSL it is part of the course to sort of connect with your mother tongue. |

| Researcher: | Yes, okay. |

| Fjodar: | Well, to be able to connect to that somehow, it is after all part of one’s identity to know from where you come, and I sort of value that and want to keep it. |

| Researcher: | Yes. |

| Fjodar: | That’s why I chose SSL. (Hedman and Magnusson 2019, pp. 10–11). |

Fjodar’s statement expresses how he relates the multilingual aspects of the SSL syllabus to “one’s identity” and sense of belonging. Other students also related to experiences working with language comparison tasks, as part of the SSL syllabus, as an important learning task (

Hedman and Magnusson 2019, p. 8). For example, Dana, a student at Rowan, emphasized how the language comparison tasks had made her more “aware” of her own language learning process. She also pointed out that this type of metalinguistic awareness was not taught in SWE, as it is not part of the SWE syllabus (interview, see

Hedman and Magnusson 2019, p. 8).

During the course of our visits, multilingual aspects emerged in the classrooms with different emphasis and orientation. As is the case with the Swedish curriculum in general, the overarching goals on multilingual development are loosely formulated, and may thus be applied by the teachers to various degrees and in different ways. However, work on contrastive linguistic tasks occurred in all three schools, as knowledge derived from such tasks forms part of the SSL course requirements, which are graded. Nevertheless, two of the teachers, Wera and Stephen, extended their focus on multilingualism beyond this specific curricular requirement. At Birch in particular, Wera was found to engage extensively in her students’ multilingual repertoire as an asset, through a teacher discourse that oriented towards empowerment of the students (

Hedman and Magnusson 2019). Wera used, for example, her own multilingualism and that of her students to illustrate different aspects of the curricular content in a theme on sociolinguistics. In this theme, she emphasized her and the students’ shared experiences of immigration and Swedish language learning in classroom interaction. She also applied an inclusive

we/us with the students by which being multilingual was targeted as something desirable and enviable (

Hedman and Magnusson 2019, p. 10). Although Swedish was never contested as the language of instruction, the multilingual repertoires became most salient in her classes (

Hedman and Magnusson 2019).

At Rowan, Stephen explicitly acknowledged the importance of the students’ languages other than Swedish, as a means for learning subject content in Swedish. Wera, however, also stressed that the students’ multilingual competencies were a resource and an asset

per se. As a corollary, students in Wera’s and Stephen’s classes expressed the value of their multilingualism and saw SSL as a place for recognition of and connection with their “mother tongues” (excerpt 3).

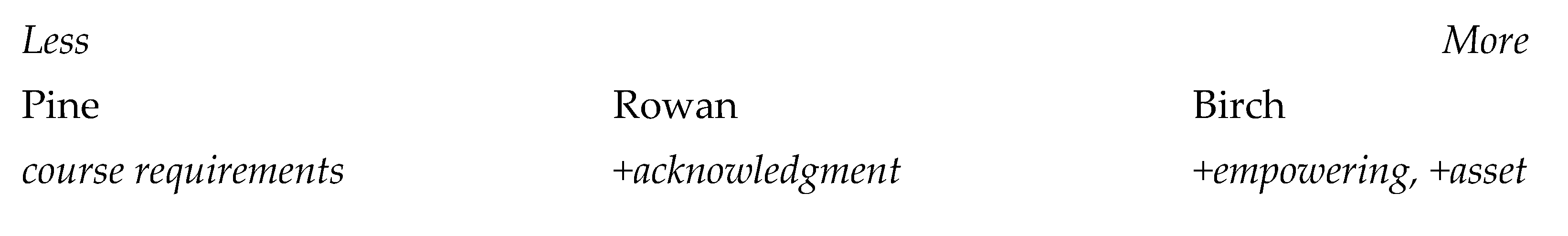

Figure 1 depicts how these curricular goals on multilingualism were interpreted and implemented to various degrees, and in different ways, in the three schools.

In sum, the curricular multilingual goals explored in

Hedman and Magnusson (

2019) were found to be enacted through empowering discourses in Wera’s classrooms–seemingly of importance for the students–and in opportunities of

learning about language, and, thus, to some extent also of

learning language (

Halliday 1993).

Learning through language (

Halliday 1993) by contrast, occurred through Swedish in all three schools (

Hedman and Magnusson 2019). When relating to the performative functions of these curricular goals, as in

Hedman and Magnusson (

2019), we also foreground the potentials of a widened curricular space for multilingualism (cf.

Hornberger 2005) to be better able to include the students’ multilingual repertoire in SSL as well as in other subjects.

2.3. Policy Friction and Ideologies on “Swedishness” and First and Second Languages

SSL as an ideologically charged educational practice also came to the fore when discussing the initial choice of opting for SSL or SWE (cf.

Leung 2019). Some of the students in our project expressed previous initial concerns regarding this choice, for example, regarding possible stigmatization of being an SSL student in terms of a hindrance for future prospects, such as future employment (cf.

Siekkinen 2021). In the three schools, there were, however, opportunities to discuss this initial choice with SSL and SWE teachers as well as study guides, on the basis of initial Swedish proficiency assessments (

Hedman and Magnusson 2020a). This initial procedure seemed to have been important for the students’ choices, along with the fact that they were free to switch to SWE if they did not want to stay in SSL. Although it was clear from our fieldwork that students sometimes shuttled between the subjects, all of the students in our study chose to stay in SSL throughout their second or third year in upper secondary school.

One essence of policy friction (cf.

Jaspers 2015) noted in our data (

Hedman and Magnusson 2020b) seems to relate to dominant societal ideologies on “Swedishness”, and to what extent students in SSL are part of this social categorization. Wera discussed whether students in SSL were perceived as “real Swedes” and expressed that it was a failure on behalf of the educational system when students born in Sweden studied SSL throughout their schooling (p. 10). Sandra, on the other hand, referred to a specific vulnerability for students in SWE who did not get appropriate support and would benefit from SSL instruction (

Hedman and Magnusson 2020b). Another aspect of policy friction concerned the related but not identical issue of who should be considered a first language speaker of Swedish and who a second language speaker, as actualized by the name of the school subject. In Wera’s teacher discourse (see excerpt 4), the complexity of the issue appeared; the excerpt begins with a student reading aloud the curricular goal requiring comparisons “between Swedish and your own mother tongue”.

| Excerpt 4. Fieldnotes from Birch (12 May 2016). |

| Student: | [reading the knowledge requirements aloud] ”in addition you are able to account for differences between Swedish and your own mother tongue”. |

| Wera: | That is where your dilemma comes now, which is my mother tongue, which is your first language? Now you know Swedish as well as you know your first language–people can learn English, different languages, okay. |

Wera problematizes the distinction between a mother tongue and Swedish, which, according to her, imposes a “dilemma” for them. As was generally the case, she marks an inclusive stance by including herself among those for whom mother tongue is ambiguous (“which is my mother tongue”). Also, she acknowledges the students’ command of Swedish as equal to that of their “first language”. By affirming the possibility of learning languages, she seemingly acknowledges a potential of language learning in which the level of command is not necessarily the key issue. Such an attitude is in line with a more dynamic view on multilingual practices and may be seen to challenge the clear-cut division implied by the upper secondary SSL syllabus.

The first/second language division also appeared in the student interviews. For example, one student claimed a self-evident second language status as a motive for her choice of SSL: “But still, well, I am convinced that Swedish is my second language so that [short laughter]” (

Hedman and Magnusson 2020a, p. 6). However, among other students who had lived in Sweden since an early age, we found a tendency to dissociate from the category of newly arrived students in the same classroom. One of these students claimed, for example, a high command of Swedish and different educational needs than theirs, and maintained that what SSL offered him was support (“language help”) in writing and giving speeches, which he distinguished from knowledge of Swedish as such (

Hedman and Magnusson 2020a, p. 9). For this student, while recognizing the advantages of SSL instruction, the prospect of being associated with beginner users of Swedish was not a welcome one. The different approaches to students’ multilingualism and the multilingual goals of the SSL syllabus, as illustrated in

Figure 1, represent an additional kind of policy friction, including different ideologies manifested in teachers’ discourses and practices.

In the following, we present our findings from the primary school, Chestnut, where we focus on our observations from the introductory classes and Swedish as a second language.