1. Introduction

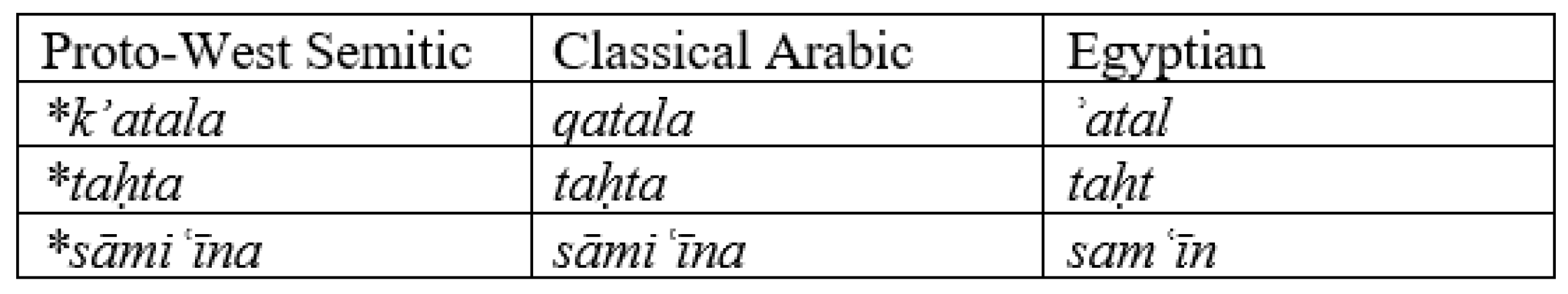

It has been widely recognized that the diverse forms of spoken Arabic today do not descend in a linear manner from the literary Arabic of medieval prose and poetry—conventionally termed Classical Arabic—or the language of the Quranic Consonantal Text (QCT), Old Ḥigāzī (for the most recent appraisal, see

Holes 2018a, pp. 1–28;

Al-Jallad 2020b, chps. 4 and 5). Indeed, when viewed through the lens of the comparative method, many modern Arabic vernaculars exhibit features that are more archaic than their Classical Arabic counterparts. Na’ama

Pat-El (

2017) has skillfully identified a number of such features in her 2017 article “Neo-Arabic and Comparative Semitics”. Clive Holes has also done pioneering work on pre-Islamic relics in the modern vernaculars of the Gulf, especially in the realm of the lexicon (

Holes 2018b, pp. 112–32).

Van Putten and Benkato (

2017) isolated relics of an earlier stratum of Arabic in loans in Awjila Berber that is distinct from the present-day dialects of Libya. And I have suggested that the phonology of the emphatics of pre-Hilalian Maghrebian Arabic may be connected to the pre-Islamic dialects of the Levant (

Al-Jallad 2015). The existence of these features implies that an unidentified stratum of Arabic that failed to achieve written form in the early Islamic period contributed to the formation of modern vernaculars.

This essay explores the possibility that such ancestors may be attested in the pre-Islamic epigraphic record. Before approaching this question, however, it is important to recognize two things. The modern vernaculars never existed in a vacuum; they have experienced considerable contact with the literary register, which has contributed significantly to their lexicons and to their grammatical structure. In addition to this, interdialectal contact has led to an amalgamation of grammatical features in living speech, ones that originate in different times and places. An obvious example of this is the verb

šāf “he saw”, which is nearly pan-Arabic today.

šāf, although presently widespread in the Maghreb, was likely a late introduction through inter-dialectal contact (

Aguadé 2018, p. 57). It is absent in Maltese, which became isolated from the Arabic sprachraum by the 13th century, and is not used in several pre-Hilalian dialects. These only know

ṛa. The same applies to the Levant. There,

šāf is the primary verb used to express “to see” in Lebanon, yet Cypriot Arabic, which originates on the Levantine coast and became isolated from the Arabic-speaking world by the 13th c. CE, does not use this etymon. Instead, it employs two verbs for “to see”—

ra (Proto-Arabic *raʾaya; Classical Arabic raʾā;

Borg 2004, p. 214) and

kišʿe (Qəltu qašaʿ;

Borg 2004, p. 388). The latter is fossilized as a presentative in Damascene Arabic,

šaʿ (

Souag 2016). While it is clear that Cypriot Arabic shares a common ancestor with the dialects of the Levant, in the intervening centuries since its isolation, a new verb for “to see” spread as a result of contact with other dialects, in this case perhaps northern Arabian ones.

Likewise, Cypriot Arabic does not know the pseudo-verb

bVdd- “to want” and instead makes use of a verb derived from the root

rwd,

piri (< *birīd “he wants”;

Borg 2004, p. 256; cf. Classical Arabic yurīdu). This it shares in common with the Qəltu dialects, while the modern dialects of the Levantine coast employ

bVdd. The latter may also find its source in the North Arabian dialects, where “to want” can be expressed with the prepositional phrase, (

i)b-widd-pn, or simply with

widd-pn, literally meaning “in

pn’s wish” and “

pn’s wish”, respectively. If we employ an archaeological metaphor, a dialect area, such as the Levant, can be regarded as an archaeological section. The layers would reflect different chronological strata of contact-based features and local innovations. While

šāf and

bVdd may reflect relatively late layers, this paper is interested in identifying the very earliest linguistic strata in the modern vernaculars.

Almost all who have discussed Arabic’s past begin its historical period with the Quran and the nearly contemporary oral poems, passed on traditionally from

rāwī to

rāwī until achieving written form in the 8th–9th centuries at the earliest. The Quran itself is far from a linguistic unity. It minimally comprises a consonantal text,

rasm, which reflects the local dialect of the Ḥigāz, while the reading traditions imposed upon it draw on various 7th and 8th c. varieties. The combination of these two linguistic types sometimes produces features that may never have been used in spoken language (

Van Putten 2021, §3.4;

Al-Jallad 2020b, pp. 57–72). Likewise, the oral poems can provide us with a glimpse of the performance language of that particular tradition, but we cannot know how much the odes changed over time as they were passed from generation to generation. Finally, their linguistic unity is little more than an assumption rather than a demonstrable fact. No one has yet, as far as I know, engaged in a truly comparative examination of the poetic tradition’s language on its own terms.

Another corpus suitable for comparison exists: pre-Islamic epigraphy.

1 These texts, which are carved in nearly half a dozen scripts, offer both advantages and disadvantages. To begin with the latter, the inscriptions do not belong to a living tradition. While the researcher has the work of early Islamic philologists to rely upon when approaching the Qaṣīdah odes and the Quran, the meaning of the pre-Islamic inscriptions must be reconstructed. However, with a proper comparative approach, and with due attention to archaeological and historical contexts, one can be confident about the meaning and grammar of a large part of the corpus. Nevertheless, the consonantal Semitic scripts that encode these ancient Arabic vernaculars provide us with a very limited view of their phonologies and morphology.

These materials come with advantages as well. We can be sure that their language was not filtered through later, Classicizing traditions. They reflect a register of Arabic used at the time they were produced, and since many are simple graffiti, they likely reflect something close the vernacular of their writers. The pre-Islamic inscriptions, moreover, stretch much further into the past than the pre-Islamic odes, as far back as the middle of the first millennium BCE if not earlier, and cover a wider geographic area, spanning from the Syrian desert to the Yemeni frontier.

As such, how can this corpus aid in the understanding of the linguistic history of the Arabic vernaculars? The answer is not straightforward. In some cases, we may posit a direct developmental trajectory between a phenomenon attested in the ancient sources, but in others, similarities may point towards parallel developments in the history of the language. The following pages will identify three features that the modern dialects share with the ancient epigraphy to the exclusion of normative Classical Arabic. I would suggest that these are reflective of the earliest linguistic layer of present-day vernacular Arabic.

2. Wawation

Proto-Arabic inherited the Proto-Semitic case system with only a few changes, including the emergence of a new declension (

Huehnergard 2017;

Al-Jallad and van Putten 2017;

Al-Jallad, forthcoming a), but the case system began to disappear in several ancient dialects of Arabic at approximately the turn of our era, mainly concentrated in the Nabataean realm (

Corriente 1976;

Blau 2006). The first stage of this process appears to have been the loss of final short vowels and then the loss of

nunation (tanwīn), which resulted in a new set of final vowels in triptotic nouns. While a couple of inscriptions attest a functional declensional system in this state, the majority situation generalizes the nominative ending in all syntactic positions.

2 This feature—conventionally termed

wawation—is encountered not only in the Nabataean inscriptions, but wherever one finds triptotic Arabic names in the Aramaic inscriptions of the first millennium BCE and the first half of the first millennium CE. Perhaps the earliest attestation of this feature in the Aramaic script is found in the 5th c. BCE votive inscription of Qaynu son of Guśam king of Qaydar at Tell Maskhūṭah, Egypt (

Rabinowitz 1956). Wawation is attested continuously throughout the centuries in northern Arabic dialects, appearing on the anthroponyms and tribal names in the Namārah inscription and even in 6th c. CE Arabic inscriptions from Syria and North Arabia (

Al-Jallad, forthcoming b).

Tell Maskhūṭah (5th c. BCE)

C zy qynw br gšm mlk qdr qrb l-hnʾlt

“That which Qaynu son of Guśam has offered to han-ʾIlat (the goddess)”

Namārah inscription (S. Syria) (328 CE)

w-mlk ʾl-ʾšryn w-nzrw w-mlwk-hm w-ḥrb mdḥgw

“He ruled the two Syrias and Nizāru and their kings and waged war upon Maḏḥigu”

Ḥarrān inscription (S. Syria) (568 CE)

ʾnʾ šrḥyl brṭlmw

“I am Šaraḥīl son of Ẓālimu”

The distribution of ancient

wawation is as follows: with a few exceptions, it appears on triptotic anthroponyms and on Arabic proper nouns. It does not attach to names terminating with the feminine ending

-at, nor does it attach to diptotic names belonging to patterns such as

fuʿal, ʾafʿal, and

fVʿlān or names defined by the article. It is reasonable to assume that this distribution applied to nouns as well, although it is impossible to prove as there are so few examples of Arabic prose written in the Classical Nabataean script. JSNab 17, an Arabic inscription carved in the Nabataean script from Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ (dated 267 CE;

see Macdonald’s contribution to Fiema et al. 2015 for the latest edition of the text), marks all triptotic nouns with wawation, including definite forms:

ʾlḥgrw = ʾal-Ḥiǧr, the ancient name of Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ,

ʾlqbrw = ʾal-qabru ‘the grave’ (

Macdonald, in Fiema et al. 2015). While wawation does not apply to anthroponyms with the definite article—for example, the name

marʾalqays (=imruʾulqays) is always written

mrʾlqys and never

mrʾlqysw—its application appears to have been extended in the realm of nominal morphology, at least in some varieties.

The

u termination is also encountered in the modern Arabic vernaculars of southwest Arabia, concentrated in the Yemeni Tihāmah, extending as far north as the dialect of Balqarn (

Behnstedt 2016, p. 81;

Greenman 1979;

Alqahtani 2015). Nouns terminating in a non-etymological

u have a distribution virtually identical to anthroponyms terminating in

waw in the ancient inscriptions: it is restricted to triptotic nouns and does not occur on nouns with the feminine ending -

at. The striking congruence of both of these systems motivated

Blau (

2006) to compare them directly. While he stops short of suggesting a genealogical relationship between the dialects of Southwest Arabia and the ancient North Arabian dialects, the particular sequences of changes required to produce a nearly identical distribution at both ends of the ancient Arabic sprachraum does suggest that the feature may share a common ancestor.

The Southwest Arabian dialects, however, attest an important difference. There are some dialects where wawation is in complementary distribution with tanwīn. The former appears in pause and the latter in context. Nöldeke was the first to hypothesize that the Nabataean

w had developed from

-un, but in these Tihāmī dialects we see the process in action. The asymmetric situation is rare, isolated to a few dialects of the ʿAsīr (

Behnstedt 2016, p. 81). Rather, most dialects of the area have generalized one form. Those on the Tihāmī coast have generalized

u while most in the ʿAsīr have only the nunated ending, either

un or

in. Thus, as

Blau (

2006) suggested, the following relative chronology appears secure (

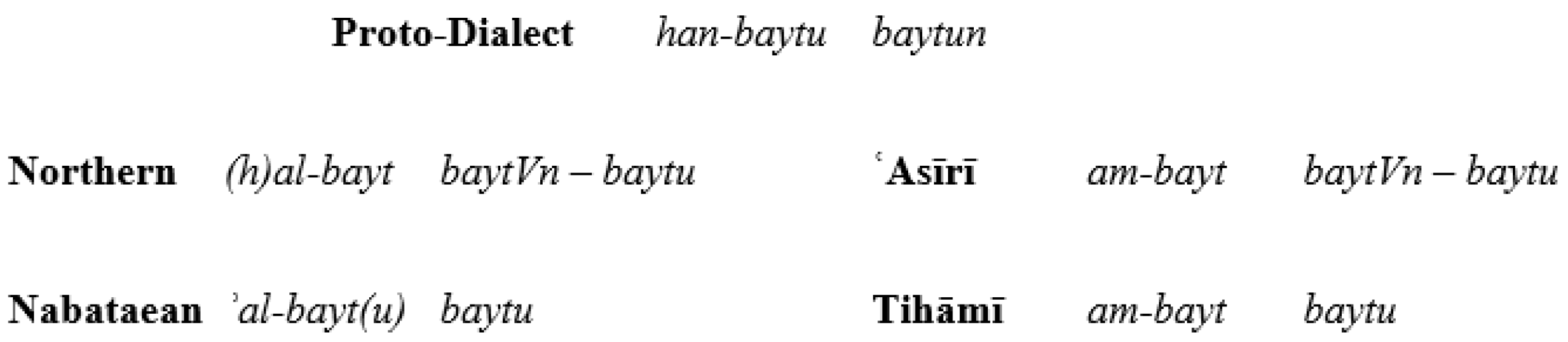

Figure 1):

Those dialects exhibiting the

baytu/baytVn opposition appear to be more archaic than the Nabataean situation at first glance, but this may simply be an accident of attestation. Since most of the nouns attested in Nabataean occur in an Aramaic linguistic setting, it may be the case that their attested forms are pausal. While there is no direct evidence for the preservation of nunation in Nabataean inscriptions, a clue might be found in the Nahal Hever papyri, which are first c. CE legal documents from the Dead Sea area. The Arabic noun for “contract” is attested with an otiose final

nūn,

ʿqdn. Although

Yardeni (

2014) suggested that this could possibly be a first person pronominal suffix, it would make little sense in this context. Rather, one could carefully hypothesize that it be interpreted as the ad-hoc writing of context form, with nunation. An even earlier example of functional nunation is attested in a widely known yet unpublished inscription from the Taymāʾ area. The text—carved in an oasis North Arabian alphabet—was authored by the king of Dūmat (mod. Dawmat al-Jandal) and can be dated to the middle of the 6th c. BCE based on its reference to the Babylonian king Nabonidus. All non-pausal, non-construct, and non-diptotic nouns terminate in a

nun.

3The Bsrn inscription

ʾn : bsrn : ʿbd : nbwnʾd : mlk : bbl : nẓrt : h-ġnm : b-mʾtn : frsn : w-mʾtn : rkb : ʾbl

‘I am Bsrn servant of Nabonidus king of Babylon; I have guarded the spoils with a cavalry unit and a unit of cameleers’

The phrase

mʾt frs “cavalry unit” is widely attested in the Safaitic inscriptions, which are about half a century later (

Macdonald 2014). The appearance of

nūns in this inscription suggest that the two words do not form a genitive construction but rather a noun and adverb,

bi-miʾatin farasan. The final word of the inscription,

ʾbl, lacks a

nūn, perhaps suggesting that it is a pausal form.

This distribution could indicate that both the ancient northern Arabic dialects and those of southwest Arabia share a common ancestor that had undergone the changes described above. Over the passage of time, each group altered the asymmetric pausal vs. context distribution by generalizing one form. The u termination was eventually favored in Nabataean and the Tihāmah while the nunated form was favored elsewhere. Some varieties of Nabataean further generalized wawated forms to the definite declension as well, producing the situation we find in JSNab 17.

If the genealogical connection between these two dialect groups is correct, then it may suggest that an ancient dialect of Arabic similar to what is attested in the Bsrn inscription moved south sometime in the first millennium CE and replaced the pre-Arabic languages of the ʿAsīr and Tihāmah.

4 We should further note that Nabataean Arabic and the dialects of southwest Arabia differ in the form of the definite article,

al and

am respectively. Thus, it is possible that the definite article of the ancestral dialect to both was

han-, as attested in the Tell al-Maskhūṭah inscription. This morpheme split into

ʾal- in the north and

ʾam in the south (on the chronology of the Arabic article, see

Al-Jallad 2021) (

Figure 2).

Wawation is today not only attested in southwest Arabia. It is also found in the Levant and Mesopotamia, where it is realized as

u or

o, depending on the dialect. It has a much more restricted distribution: the feature is found on high frequency kinship terms, such as Levantine Arabic

ʿammu “paternal uncle”,

ḫālu “maternal uncle”,

sīdu “grandfather”,

ǧaddu “idem.”, and on feminine nouns,

ḫāltu “maternal aunt”, etc. In northern Mesopotamia the

u/o-termination applies only to masculine kinship terms, while feminine nouns terminate in

-a; in Mardin, feminine vocative nouns terminate in -

e. This distribution speaks against viewing the suffix as a third person masculine singular clitic; there would be no reason that it should be restricted to masculine nouns.

Grigore (

2007, p. 203) suggested that, at least for the dialect of Mardin, the termination could have a Kurdish source, but Procházka favors a Semitic origin as its distribution extends far beyond the areas in which Persian or Kurdish influence would seem possible (

Procházka 2020, pp. 95–96). If I may go further, I would suggest, given the broader Arabic context, that the

u/o-termination is a reflex of wawation as attested in Nabataean and in the southwestern Arabic dialects. The distribution in the Mesopotamian dialects matches the situation in Nabataean—it does not apply to nouns terminating in the feminine ending. The etymology of the feminine

-a remains unclear. Perhaps

Grigore (

2007, p. 203) is correct to see a connection with Kurdish. While the masculine wawated form would have had an Arabic origin, speakers could have understood it as the same morpheme as the Kurdish vocative ending in a bilingual setting. The absence of any marking on feminine kinship terms perhaps motivated the borrowing of the Kurdish feminine ending to produce an etymologically mixed paradigm nearly identical with the Kurdish vocative paradigm.

The Levantine dialects appear to have extended the domain of wawation through analogy, appending the suffix to the female counterparts of male kinship terms; a similar extension of nunation occurred in Classical Arabic as

Van Putten (

2017) convincingly reconstructs the feminine ending as diptotic in Proto-Arabic.

The Levantine situation may, therefore, reflect a continuation of ancient Nabataean-type wawation, which survived marginally while the rest of the nominal system shifted—either through contact or through internal development—to favor the non-wawated paradigm. The early 6th century CE Arabic inscription from Jebel Usays

5 already demonstrates that the local Levantine dialects of Arabic had dispensed with wawation on personal names and nouns; thus, it is already possible at this point that the feature was restricted to kinship terms. It is not surprising that kinship terms would preserve older layers of morphology, and so this solution, if correct, would provide a unified analysis of wawation across Arabic.

To conclude, the linguistic stratum of wawation in the Levantine and northern Mesopotamian dialects, the ancient dialects of the southern Levant, and the modern Tihāmī and ʿAsīrī dialects would appear to share a non-Classical Arabic common ancestor with this distinct declensional profile.

3. 1CS Genitive Clitic Pronoun

The next feature I would like to consider is the 1CS genitive clitic pronoun. In all forms of Arabic, the shape of this pronoun is dependent upon the termination of the noun to which it attaches, as in other Semitic languages, but its distribution can vary from dialect to dialect. The pronoun has two allomorphs:

-ī and

-ya.

| *ī | |

| | Classical Arabic: conditioned—following short vowels or consonants: kitāb-ī

Ugaritic: conditioned—ø = /ī/on nominative singular + fem. pl. nouns

Phoenician: conditioned—ø = /ī/, nominative + accusative |

| *ya | |

| | Classical Arabic: conditioned—following long vowels and diphthongs: ʿalay-ya

Gəʿəz: unconditioned—hagaré-ya

Ugaritic: conditioned—y = /ya/, gen + acc singular, and other nouns; on prepositions

Phoenician: conditioned—y = */ya/, genitive nouns |

Some contemporary Arabic dialects, most notably those spoken in North Africa, employ the *ya allomorph following certain prepositions: Maghrebian liya “to, for me”; biya “in/by me”, in contrast to normative Classical Arabic lī and bī, respectively. This distribution may in fact not be innovative. Various Quranic reading traditions produce such forms, but perhaps more importantly, the rasm itself demonstrates that this allomorph was in existence and had a much wider distribution.

Quran

69:19 |

| فَأَمَّا مَنْ أُوتِىَ كِتَـٰبَهُۥ بِيَمِينِهِۦ فَيَقُولُ هَآؤُمُ ٱقْرَءُوا۟ كِتَـٰبِيَهْ |

faʾammā man ʾūtiya kitāba-hū bi-yamīni-hī fa-yaqūlu hāʾumu qraʾū kitāb-iyah

“and whosoever has received his record in his right hand will exclaim—Behold! Read aloud my record” |

| 69:20 |

| إِنِّى ظَنَنتُ أَنِّى مُلَـٰقٍ حِسَابِيَهْ |

ʾinnīḏ̣anantu ʾannī mulāqinḥisāb-iyah

“I had thought that I would surely face my doom” |

| 69:28 |

| مَآ أَغْنَىٰ عَنِّى مَالِيَهْ |

mā ʾaġnā ʿannī māl-iyah

“My wealth has not availed me” |

In Sūrat al-Ḥāqqah, the termination

iyah, where the final

h should be understood as

hāʾu s-sakt, i.e., a pausal

h following a short vowel, is used on nouns that are syntactically nominative (

māliyah) and accusative (

kitābiyah and

ḥisābiyah). The employment of the

ya allomorph in these contexts is certainly motivated by rhyme, but there are other places in the Quran that demonstrate that its conditioning environment was slightly different from normative Classical Arabic. The vocative expression in Quran 12:84, ىاسڡى, is read by Ḥafṣ as

yā ʾasafā and by al-Kisāʾī as

yā ʾasafē, translated as “woe to me” (lit. O my woe). Q 5:31 attests a similar construction, ىوىلىى, Ḥafṣ

yā waylatā, al-Kisāʾī

yā waylatē. The

alif maqṣūrah, read by Ḥafṣ as

ā and al-Kisāʾī as

ē, reflects the outcome of an original triphthong, *

yā ʾasafa-ya >

yā ʾasafē (Old Ḥigāzī; al-Kisāʾī) and

yā ʾasafā (Ḥafṣ) (

Al-Jallad and van Putten 2017, pp. 113–14). Thus, these expressions preserve a situation where Arabic deployed the

ya suffix following a short /a/, the accusative. Finally, in agreement with the modern North African varieties, the first person clitic following the preposition

li- is sometimes realized as

ya, depending on the reading tradition. Ḥafṣ reads لى as

liya, for example, in Q 36:22.

The pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions also attest a different distribution of the -

ya allomorph. The Safaitic inscription BES15 799 attests a construction that is identical to the Quranic use of the -

ya allomorph in the vocative.

6BES15 799

wgd sfr bny f ṯql ʿl-bny w qlḫbly

“he found the inscription of Bonayy and was weighed down (by grief) on account of Bonayy and said: woe to me (ḫabla-ya lit. O my woe)”

The use of the

-ya allomorph following the short high vowel /i/ is also attested in the pre-Islamic corpus. A Thamudic D inscription from the northern Ḥigāz attests this allomorph following the preposition

bi.

7UdhThamD 1 = JSTham 213

rbt śq by ʾ{l} kn ʾmt śkrn

‘There is much longing in me (biya) for Kn the maidservant of śkrn.’

Finally, the Dumaitic inscription WDum 3 = WTI 23 attests the

-ya allomorph on a noun which is syntactically in the genitive case. Its presence implies that the genitive ending was still productive in this stage of the language.

8WDum 3; WTI 23

h rḍw w nhy w ʿtrsm sʿd-n ʿl-wdd-y

‘O Ruṣ́aw and Nuhay and ʿAttarsamē, help me in the matter of my wish (widādiya)’

The combination of these facts indicates that the Proto-Arabic distribution of the

ī and

ya allomorphs of the 1CS genitive pronoun was different from normative Classical Arabic. Rather, its appearance following the accusative in vocatives /a/, and short /i/, following prepositions like

li and

bi, and the genitive in Dumaitic, indicates a distribution similar to Ugaritic. Thus, we can reconstruct the Proto-Arabic situation as such:

| Nouns |

| Nom: *gamal-ī |

| Gen: *gamali-ya (Attested: Dumaitic; relics: QCT) |

| Acc: *gamala-ya (Relics: vocative in QCT and Safaitic) |

| i-vowel prepositions: |

| *li-ya |

| *bi-ya |

| Long vowels + diphthongs |

| *ʿalay-ya |

| *yadā-ya |

In this light, modern vernaculars that exhibit forms such as biya and liya continue the ancient situation, while Classical Arabic is innovative in its generalizing of the -ī ending to these propositions. As one reviewer of this paper pointed out to me, the quality of the vowel of the preposition in the Maghrebian varieties suggests that its immediate ancestor was long, liya < *līya. Maghrebian Arabic generally loses etymologically short vowels, except in unstressed function words, where they are reanalyzed as long, e.g., the third masculine plural pronoun hūma < hum. Thus, an original *liya would have plausibly yielded līya; the same applies to the form biya.

The vocative form may also be attested in some modern dialects. In some Levantine dialects, the expression yābāye is used in situations of distress. It translates literally as “O my father.” If the expression goes back to *yā ʾabā-yah, with hāʾu s-sakt, then it would parallel similar constructions in the Quran and Safaitic.

Hāʾu s-sakt must be reconstructed for the ancestor of the forms

liya and

biya as well. The presence of a final

a in these cases is anomalous, as final-short vowels, including

a, have generally been lost in the modern vernaculars (

Figure 3).

Thus, the survival of the vowel suggests the presence of a final h, protecting it from apocope. In other words, the antecedent of dialectal biya was not *biya but rather *biyah, as attested in Sūrat al-Ḥāqqah.

To conclude, both the distribution and form of the 1CS genitive clitic pronoun in the modern dialects speaks against a Classical Arabic origin, but should rather be connected with phenomena attested marginally in the QCT and in the ancient inscriptions.

4. Relative Pronoun

The relative pronoun

ʾallaḏī is restricted to southwest Arabia today (

Behnstedt 2016, p. 74), but in former times it was much more widely distributed (

Holes 2018a, p. 13). It is the primary form attested in Middle Arabic texts, even those that are quite close to the vernacular. It is attested in the Damascus Psalm Fragment as ελλεδι (8th–early 9th c.; Al-Jallad 2020b, p. 26). If this form was common in medieval vernaculars, it has today given way to the virtually pan-Arabic relative pronoun *

ʾalli (

Stokes 2018). Yet

allaḏī seems to have spread at the expense of an earlier relative pronoun

ḏVː. To the Arabic Grammarians,

ḏVː was characteristic of the dialects of southwest Arabia, where it can still be heard today, and the Najdi dialect of Ṭayyiʾ (

Rabin 1951, chps. 3 and 14). In the modern dialects,

ḏ-base relatives are common in Southwest Arabia (

Behnstedt 2016, p. 74) and in the Maghreb (

Aguadé 2018, p. 54). The genitive particles

ḏīl and

ḏēl (lit. “that which is for”) in the Qəltu dialects and marginally in the Levant also suggest that at one point the relative pronoun of those dialects was a simple

ḏ-base form (

Procházka 2018, p. 280;

Lentin 2018, p 195).

The relative

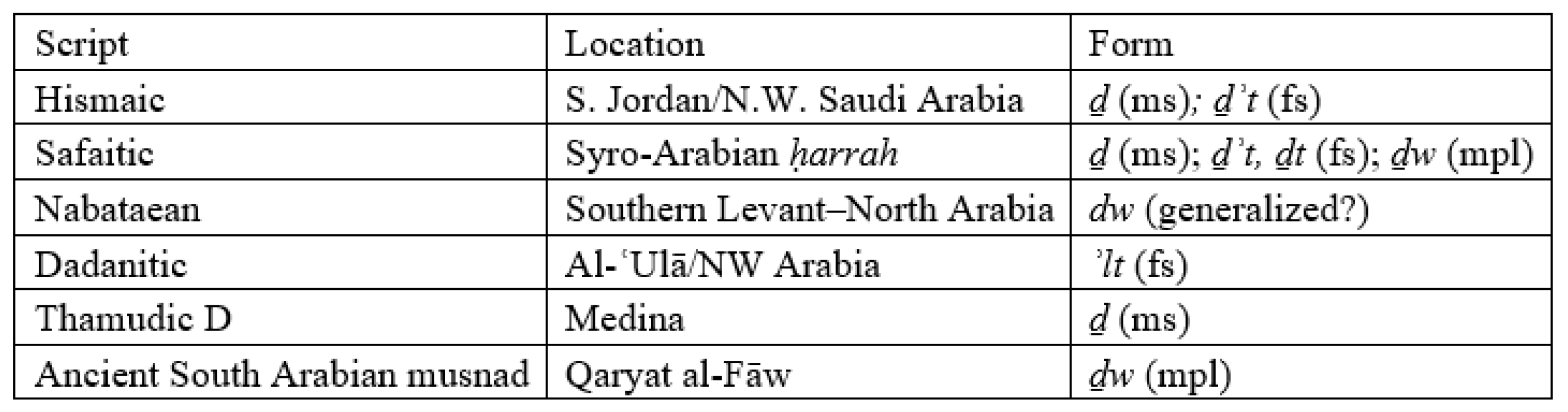

ḏVː is attested across the pre-Islamic Arabic Sprachraum (

Figure 4)—indeed, the form

ʾallaḏī has not yet appeared in the pre-Islamic epigraphic record, although its feminine counterpart

ʾallatī has been attested once in the Ḥigāz.

In at least Safaitic and Hismaic it seems to inflect for case, gender, and number, with the plural form appearing as

ḏw /ḏawū/ or /ḏawī/). Even as far south as Qaryat al-Faw, in the linguistically mixed inscription from the site, the Rbbl bin Hfʿm grave inscription, the plural form is attested as

ḏw (

Beeston 1979;

Al-Jallad 2014). In Safaitic the relative may rarely agree in definiteness with its antecedent, producing

hḏ /haḏḏī/.

The presence of the

ḏ-base relative pronoun in all other branches of Semitic permits its secure reconstruction to Proto-Arabic, although there is not enough information to determine the details of its inflectional paradigm (

Huehnergard 2017, pp. 16–17). This in turn indicates that the *

ʾallaḏī and later *

ʾalli forms are innovative, and spread at a later period, similar to

šāf and

bVdd discussed in the introduction.

Since

ḏVː is an archaism it cannot be used to argue for a shared genealogical relationship between the dialects that preserve traces of it. It does, however, demonstrate that these dialects do not descend linearly from Classical Arabic, which had replaced this form with the

allaḏī-type relative. Moreover, its presence throughout pre-Islamic Arabic prevents us from assuming that the

ḏ- base relative pronoun in the modern vernaculars is a result of “South Arabian” influence, as has been previously suggested (

Corriente 2007). The relative was not bound to a single geographic area in pre-Islamic times, but was in use from Yemen to Syria. Rather, it was the

allaḏī-type relative that appears to have had a specific geographic distribution, restricted to the Ḥigāz. Today’s dialect geography reflects a reversal of the pre-Islamic situation. The

allaḏī-type relative, including *

alli, has spread at the expense of the older

ḏ-type, which is today restricted to the periphery of the Arabic

sprachraum.