1. Introduction

Raising to Object (henceforth RtoObj), like other types of Raising configurations, features a determiner phrase (DP) in a dual-clausal relationship with both the matrix and the embedded clauses. Consider Example (1).

| 1. | John believes Mary to be intelligent. |

In (1), Mary is thematically linked to the infinitival complement—‘Mary’ is an argument of ‘being intelligent’. At the same time, it has the grammatical function of object in the matrix clause, as is revealed using common tests, such as passivization or case morphology:

| 2. | a. | Mary is believed to be intelligent. |

| | b. | She believes him to be intelligent. |

RtoObj is possible in English and a few other languages, most famously, Icelandic. RtoObj appears very infrequently in corpora (

Heil 2015). The set of verbs that allow RtoObj is small but coherent: ‘accept’, ‘affirm’, ‘assume’, ‘believe’, ‘conclude’, ‘confirm’, ‘consider’, ‘guess’, ‘imagine’, ‘presume’, ‘proclaim’. They have in common that they denote an epistemic state and cannot select infinitivals consisting of bare dynamic predicates (see

Heil 2015 for detailed description). However, RtoObj is not possible in many other languages, such as Spanish. Example (3) shows this:

1| 3. | * | Juan cree | a María ser | inteligente. |

| | | Juan believes | acc Maria be.inf | intelligent |

The contrast between (1) and (3) raises the question of what feature or features differentiate Spanish from English and give(s) rise to the distinct acceptability judgments. As far as we can tell, insight into what licenses RtoObj is largely speculative. Additionally, RtoObj has limited cross-linguistic distribution, which creates additional difficulty to further investigate the question of licensure. The main goal of this paper is to limit the range of possible hypotheses by pinpointing the source of the cross-linguistic difference.

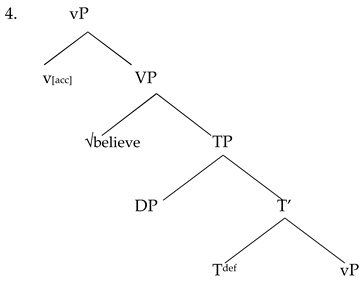

The licensing of a RtoObj structure requires the presence of two features in the syntactic structure: a feature in the matrix clause and a feature in the infinitival complement. Let us use the abstract tree in (4) to illustrate the discussion:

![Languages 06 00172 i001]()

RtoObj involves a functional feature in the matrix clause that establishes a dependency with an argument in the lower clause—hence, the accusative case and the object-like property of the raised DP. This functional feature must be able to probe into a subordinate clause. In our structure in (4), and following a tradition that begins with

Chomsky (

1995), we take it that the head that assigns accusative case to the argument of the lower clause is

v.

Additionally, RtoObj requires a feature in the infinitival complement that makes it transparent for a probe in the matrix clause. Following a line of thinking that originates in

Chomsky (

1995), we assume that English epistemic verbs can select a deficient T phrase (T

defP) that is unable to license an overt or covert DP, with the consequence that the thematic subject of the infinitival complement must establish a dependency in the matrix clause.

Since RtoObj requires two features in the structure, the absence of RtoObj in Spanish could come about due to the absence of one of these features in the Spanish inventory. One possibility is that the Spanish v does not have the ability to probe lower than a TP barrier. Alternatively, the absence of RtoObj in Spanish would suggest that epistemic verbs cannot select for Tdef or that Spanish lacks this category altogether.

Thus, the question that this article addresses is: What makes English and Spanish distinct—is it the matrix

v or the subordinate T

def? In order to extricate the feature or features that yield RtoObj, we propose using code-switching data. As we shall show, code-switching by deep bilinguals—those that acquired both languages from a very early age and continued to develop both languages into adulthood (see

López 2020 for discussion of the concept of ‘deep bilingual’)—helps us set the laboratory conditions to investigate alternative hypotheses.

Let us say a few words about intra-sentential code-switching. For starters, let us introduce an example that appeared in the Facebook feed of one of the authors of this article:

| 5. | Antes de que se vaya, thank President Obama for everything he’s achieved. He’s worked hard to protect and defend nuestros terrenos, nuestro aire, nuestras aguas, nuestras comunidades, y nuestra madre tierra. Add your name to our thank you letter today! |

| | (“antes de que se vaya” = “before he leaves”) |

| | (“nuestros terrenos, nuestro aire, nuestras aguas, nuestras comunidades, y nuestra madre tierra” = our land, our air, our waters, our communities and our mother earth”) |

As you can see, constituents from both English and Spanish find their way into the structure of the clause. For deep bilingual speakers, code-switching should be regarded as an integral component of their linguistic competence. Consequently, there are rule-governed instances of code-switching and unacceptable instances and deep bilingual speakers can provide acceptability judgments on code-switched sentences just like they do with monolingual sentences.

Many linguists who focus on code-switching assume the

No Third Grammar Approach (

MacSwan 1999). Under the No Third Grammar approach, any unacceptability that arises in code-switching is due to restrictions inherent to the two languages themselves rather than a separate, code-switching-specific rule system. We fully endorse this assumption, which is foundational in our code-switching work.

In light of the previous discussion, consider the following fabricated code-switching sentences:

| 6. | I believe John | serinteligente. | Eng/Span | |

| | | be.inf intelligent | | |

| 7. | Creo | a | Juan to be intelligent. |

| | believe.1 | acc | |

In the first sentence, the matrix predicate is in English while the subordinate clause is in Spanish. In the second sentence, it is the other way around. Will these sentences be acceptable to Spanish/English bilingual code-switchers? The No Third Grammar Approach informs our understanding of RtoObj and, therefore, we expect that certain combinations will be acceptable to code-switchers, whereas others will not be only on the basis of the features that appear in the structure (4). If a property of the matrix predicate licenses RtoObj, (6) should be acceptable because the matrix clause is in English and, therefore, so is the matrix v. On the other hand, if a property of the subordinate clause licenses RtoObj, then (7) should be acceptable, because the subordinate clause is in English.

In this article, we present data that support the second option: English/Spanish bilinguals accept (7) and reject (6). We find that early Spanish/English bilinguals overwhelmingly prefer code-switched RtoObj samples when the infinitival complement is in English and they reject RtoObj when the complement is a Spanish infinitival. Consequently, English TdefP is linked to the licensing of RtoObj. This suggests that Spanish Tdef is either different or altogether missing as a grammatical ingredient.

The paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we discuss RtoObj more formally, and we introduce two related phenomena: Raising to Subject and Object Control.

Section 3 discusses code-switching as a means of analyzing the nature of RtoObj and introduces our research questions.

Section 4 presents the study, including methods, and results. The discussion and conclusions appear in

Section 5 and

Section 6, respectively.

2. Raising

Raising to Subject (RtoSubj) (8) and RtoObj (9) are characterized by having a non-finite complement and a DP that is simultaneously in a thematic relationship with a predicate in the subordinate clause and in a grammatical dependency with a predicate in the matrix clause.

| 8. | Raising to Subject |

| | Ludwig seems to be talented. |

| 9. | Raising to Object |

| | Wolfgang believes Ludwig to be talented. |

In both the RtoSubj (8) and RtoObj (9) examples above, the DP in a dual-clausal relationship is Ludwig, which receives its θ-role from the adjective in the small clause that belongs to the non-finite complement. In this way, the proposition of the complement in both (8) and (9) is that Ludwig is talented.

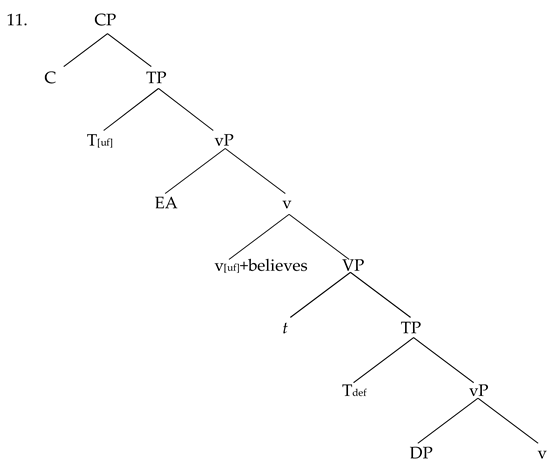

What differs for the DP between (8) and (9) is its relationship with the matrix clause. To make our discussion more explicit, we adopt a fairly standard view on clause structure, the one in

Chomsky (

2000) and represented in (10) and (11):

![Languages 06 00172 i002]()

![Languages 06 00172 i003]()

That is, we assume two relevant functional categories in the clause, T and

v. Both of them can establish dependencies with a DP argument. In Case Theory terms, we say that T assigns nominative case and

v accusative case. Additionally, we adopt the broad outlines of the Agree (p,g) framework of

Chomsky (

2000). The idea is that syntactic dependencies are established when a functional category with a bundle of unvalued features (the probe) finds in its c-command domain a constituent with matching valued features (the goal). If the probe bears an EPP feature, it can attract the goal and form a spec position.

Both examples in (8) and (9) have in common that the non-finite T of the subordinate clause does not have any φ-features that would establish a dependency with the DP argument in the subordinate clause. This is what we called Tdef above. This lack of φ-features on Tdef makes the DP available to a higher probe. Examples (10) and (12) represent a RtoSubj structure. The v in the matrix predicate is an intransitive v without φ-features. The DP eventually establishes a dependency with the φ-features of the matrix T. If Case Theory is assumed, the DP receives the nominative case. Examples (9) and (13) represent RtoObj. Here, the v of the matrix clause is a transitive v in full possession of φ-features, which are valued against the φ-features of the DP: it is said that the DP receives accusative case.

English clearly has an EPP feature in T acting in conjunction with Agree. As a result, the DP of the subordinate clause in a RtoSubj structure raises and merges with T, forming a spec. This is shown in (10) and again in (12). As for RtoObj, we are not certain that

v triggers movement of the DP (despite some arguments in

Bowers 1993) and, therefore, we provide two choices, (13a) and (13b). In (13a),

Ludwig has raised out of the subordinate clause; in (13b), it stays in situ. The assumption that the argument in RtoObj constructions stays, in fact, in the subordinate clause was predominant in the 1980s and led to the alternative moniker, Exceptional Case Marking (ECM). For our purposes, the decision between (13a) and (13b) is not crucial.

| 12. | Raising to Subject |

| | Ludwigi seems [TdefP ti to be talented] |

| 13. | Raising to Object with (13a) and without (13b) movement |

| | a. Wolfgang believes Ludwigi [TdefP ti to be talented] |

| | b. Wolfgang believes [TdefP Ludwig to be talented] | “ECM” |

As mentioned, RtoObj is not possible in Spanish (15). However, RtoSubj is fine (14).

| 14. | Ludwigi parece | ser | talentoso. |

| | Ludwig seems | be.inf | talented |

| 15. | *Wolfgang cree a Ludwig ser talentoso. |

| | Wolfgang believes ACC Ludwig to be talented |

The unacceptability of (15) poses an interesting puzzle for syntactic theory. What is the property or properties that leads to the difference between (9) and (15)? Now we have the tools to pose this question a little more formally than in the introduction. One possibility is that matrix

v has different properties in English and Spanish: the English

v can establish a dependency long distance, while Spanish

v cannot. The other possibility is that the subordinate T has different properties. The complement of epistemic verbs in Spanish does not select a T

def: the non-finite T projects a minimality barrier that prevents an outside probe to reach inside the TP. Notice that this second solution leads to another question: why is (14) grammatical? Is the absence of a T

def a property of epistemic verbs only or is it a general property of Spanish? If the second, should the Spanish lack of T

def also not prevent RtoSubj? There is in fact a proposal along these lines in

Ausín (

2001). He argues that RtoSubj in Spanish involves, in fact, raising out of a vP and not out of a TP

def. If so, then T

def simply does not exist in Spanish and verbs such as

creer ‘believe’ select a CP, like regular attitude verbs. We leave the question open at this point and go back to it in

Section 5.

3. Code-Switching as a Tool

One way to learn about languages is to study speakers’ I-languages via elicited judgments of acceptability. The intuitions used in the study of I-languages are typically monolingual intuitions on the consultants’ native language, but deep bilinguals can also provide consistent acceptability judgments about code-switched stimuli (see

González-Vilbazo et al. 2013 for further discussion). We assume that code-switching judgments reflect the I-language of bilinguals in the same way that monolingual intuitions reflect the I-language of monolinguals.

Additionally, we assume a No Third Grammar approach (

González-Vilbazo and López 2012;

MacSwan 1999;

Woolford 1983), which states that there is no code-switching-specific rules and restrictions. Instead, code-switching restrictions emerge as a result of the interaction of the properties of the participating languages as well as common universal properties.

In this article, we expand the use of code-switching to better understand RtoObj as well. Recall the fundamental question that we posed above: What property or set of properties allows RtoObj in English, and how is it disallowed in Spanish? Recall also that we proposed two possible accounts: either a property of the matrix

v or a property of the T in the subordinate clause teases the two languages apart. In code-switching contexts, the two options lead to distinct predictions. Consider the following two sentences:

| 16. | I believe John ser inteligente. | Eng/Span |

| 17. | Creo a Juan to be intelligent. | Eng/Span |

In sentence (16), the matrix

v is English while the subordinate T is Spanish. In sentence (17), the reverse is the case:

v is Spanish and non-finite T is English. These yield the following two predictions, which we now state formally:

| 18. | Prediction 1: English Matrix Clause Preferred |

| | If RtoObj is licensed by a property of the matrix clause, code-switched RtoObj with an English matrix clause should be preferred. Example (16) should be judged as better than (17). |

| 19. | Prediction 2: English Complement Preferred |

| | If RtoObj is licensed by a property of the non-finite complement, code-switched RtoObj with an English complement (17) should be judged as better than (16). |

Notice that the predictions in (18) and (19) arise due to the impossibility of RtoObj in Spanish.

In order to tighten up our argument, we included Object Control (ObjC) sentences in our study. ObjC sentences are superficially similar or identical to RtoObj sentences, but their underlying syntax is very different. ObjC structures are available in Spanish as well as English. Example (20) is an ObjC in English, (21) in Spanish, and (22) represents the syntax of an ObjC sentence:

| 20. | Mary persuaded John to be honest. |

| 21. | Maria persuadió | a Juan de | ser | honesto. |

| | Maria persuaded | acc Juan of | be.inf | honest |

| 22. | Mary persuaded John [PRO to be honest] |

As indicated in (20), the object of an ObjC verb is in fact a member of the θ-structure of the matrix predicate; this is the major difference with RtoObj, where the DP that plays the role of the object receives no θ-role from the matrix predicate. By hypothesis, the non-finite T of ObjC sentences includes a silent subject whose reference is dependent on the controlling object. This realization is what led to the analysis of ObjC as in (22), where the subordinate predicate has a silent argument referred to as PRO.

2We decided to include ObjC in our study as a necessary contrast with RtoObj. Since ObjC is possible in both English and Spanish, no code-switching configuration is predicted to result in unacceptability—mutatis mutandis. Thus, switches with English matrix clauses and English infinitival complements should provide equivalent acceptability judgments. Both English matrix (23) and English complement (24) are expected to be equally acceptable.

| 23. | I persuade John ser honesto. |

| 24. | Persuado a Juan to be honest. |

Switches with English matrix clauses and English infinitival complements should provide equivalent acceptability judgments for (23) and (24). Thus, testing the acceptability of ObjC in code-switching grounds our analysis and provides additional evidence that the methodology employed here is on the right track. In sum, we propose the following research question (25) and hypotheses (26) and (27) with regard to the whether the matrix clause or the complement is in English.

| 25. | Research Question |

| | Do deep Spanish/English bilinguals rate code-switched sentences differently by whether the English clause is matrix (CP1) or embedded (CP2) for RtoObj or ObjC? |

| 26. | Hypothesis 1—Raising to Object |

| | There will be a difference in rating between English CP1 and English CP2 because RtoObj exists in only one of the languages, resulting in lacking some property or properties in one or more combinations. |

| 27. | Hypothesis 2—Object Control |

| | There will be no difference in rating between English CP1 and English CP2 because Object Control exists in both languages, allowing its necessary properties to be available in all combinations. |

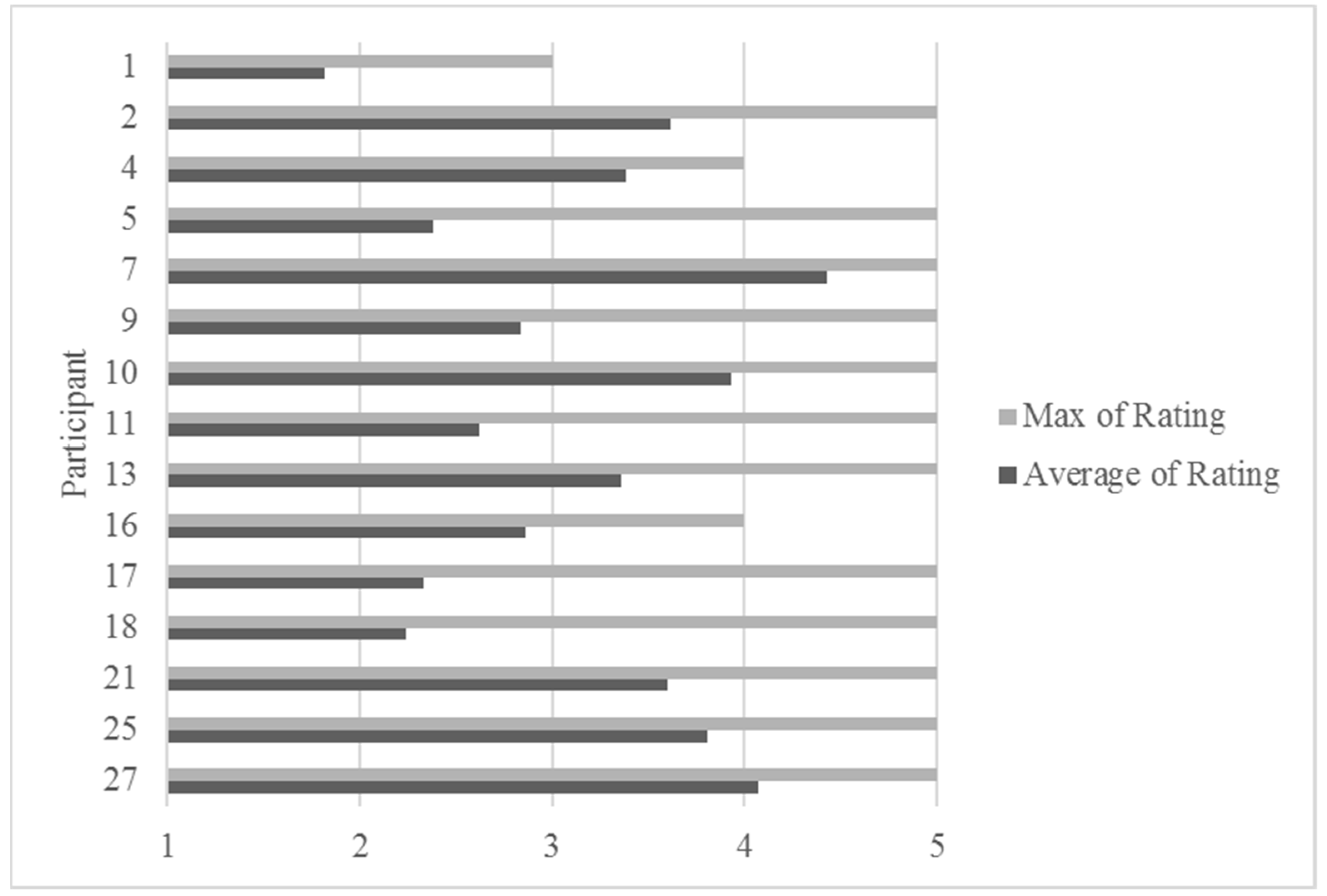

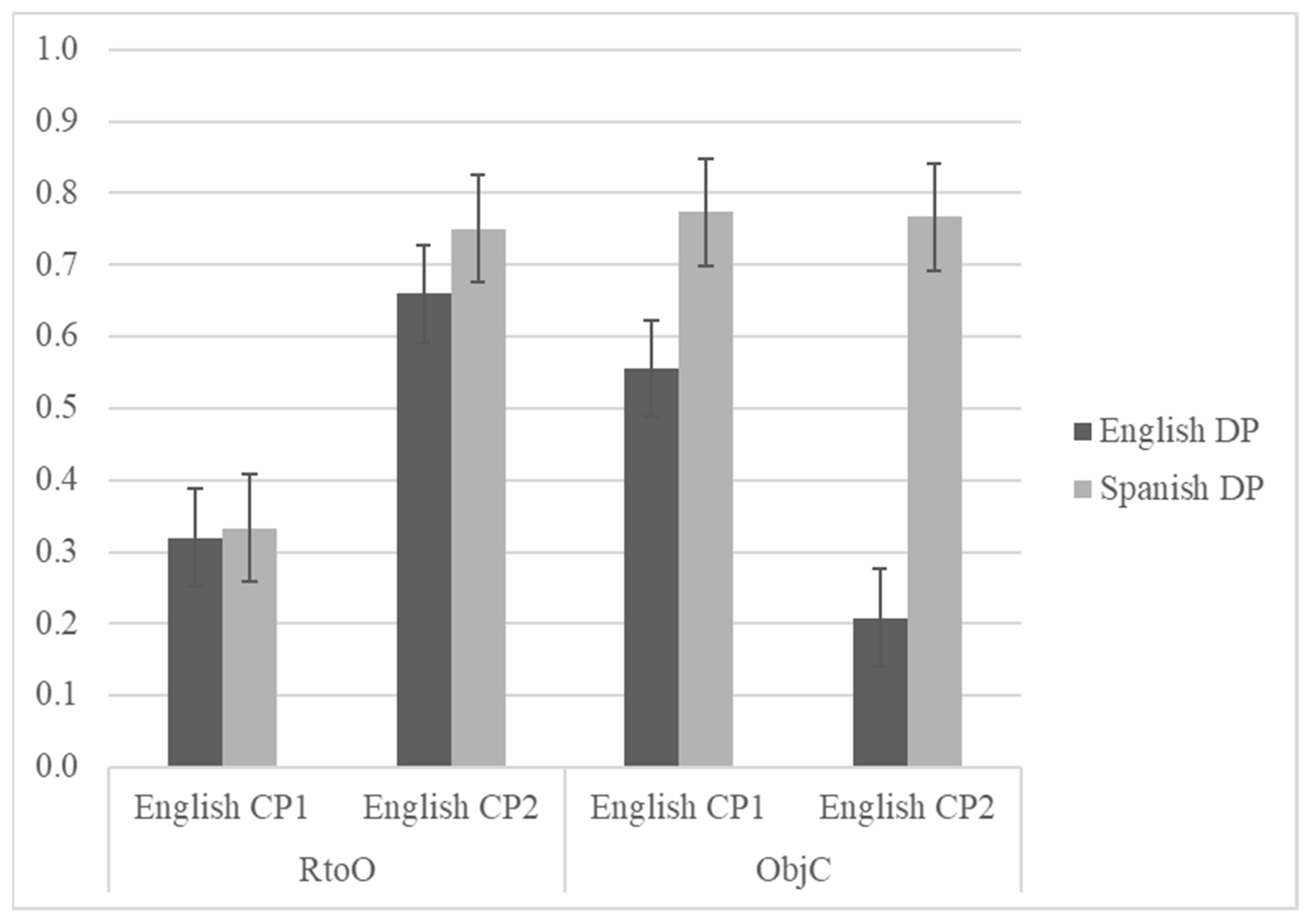

5. Discussion

It is not surprising that an effect for English CP1/2 was only found for Raising to Object. We put forth two predictions, repeated as (32) and (33) below.

| 32. | Prediction 1: English Matrix Clause Preferred |

| | If Raising to Object is licensed by a property of the matrix clause, code-switched Raising to Object with an English matrix clause should be preferred. |

| 33. | Prediction 2: English Complement Preferred |

| | If Raising to Object is licensed by a property of the non-finite complement, code-switched Raising to Object with an English complement should be preferred. |

Prediction 2 (33) was corroborated: structures with a Spanish matrix and an English non-finite complement were accepted more than twice as often (M = 0.707) as the structures with an English matrix complement (M = 0.329) and a Spanish subordinate clause. The same is not true of ObjC, with similar acceptance rates for English complement (M = 0.629) and English matrix clause (M = 0.700). The OC data confirm that the difference in acceptability between an English subordinate clause and a Spanish subordinate clause in RtoObj is indeed linked to a property of T that is specific to raising constructions and not of control constructions.

As we see above, RtoObj in code-switching contexts is very much preferred when the non-finite T is English. We take it then that the property that makes RtoObj grammatical in English and ungrammatical in Spanish resides in the complement clause and not in the matrix

v. This result is consistent with

Chomsky’s (

1981) proposal that RtoObj should be analyzed as resulting from transparency of the non-finite T to external government, what he called Exceptional Case Marking, which became reanalyzed as the T

def property of

Chomsky (

1995). However, this result leads to another puzzle. As shown in Example (14), Spanish allows what appear to be RtoSubj sentences. It is commonly assumed that RtoSubj sentences should require a T

def in the subordinate clause as well. If T

def is part of the repertoire of Spanish grammar, we need to explain why T

def is not available with epistemic predicates to form RtoObj sentences.

Here, are the options. Option 1 would be to stipulate this property of verbs such as

creer ‘believe’,

considerar ‘consider’,

esperar ‘expect’: they simply cannot select for T

def. Option 2 is the more intriguing one: despite appearances, there is no T

def in Spanish at all. What appear to be instances of RtoSubj in Spanish actually do not involve a TP at all but a Small Clause structure consisting only of a vP, as in (34). Epistemic verbs select a regular complement clause (TP or CP).

| 34. | María parece [vP t ser lista] |

| | ‘Maria seems to be clever.’ |

To our knowledge, the only proposal that assumes no T

def in Spanish is

Ausín (

2001), and Ausín’s proposal is controversial (see, e.g.,

Gallego 2007). The evidence against T

def in Ausín is due to his analysis of RtoSubj verb

parecer. In particular, he argues that

parecer + infinitive is a modal construction.

Ausín analyzes

parecer with infinitivals, such as (30), as a modal verb based on observations from

Fernández-Laboranz (

1999). First, neither

parecer nor typical modals such as

deber (‘should’) and

poder (‘can’) can pseudo-cleft (31–32).

| 35. | *Lo que {puede, debe, parece} Juan, es saber la noticia. |

| | ‘What Juan {can, must, seems to}, is to know the news.’ |

| 36. | Lo que {pretende, desea} Juan, es saber la noticia. |

| | ‘What Juan {hopes (for), desires}, is to know the news.’ | (Ausín (2001): (98)) |

Further, modals cannot be the only verb in simple matrix questions (33–34).

| 37. | *¿Qué parece/puede/debe Juan? | |

| | what can/must Juan | (Ausín (2001): (99)) |

| 38. | ¿Qué pretende /desea Juan? | |

| | What hopes for/desires Juan? | |

| | ‘What does Juan hope (for)/desire?’ | |

Based on the evidence in (35)–(38), Ausín concludes that

parecer + infinitive is a modal verb, and he proposes that its complement is a VP/vP in examples such as (34).

7 We can adopt Ausín’s insights to account for the results found in this investigation: The reason why there is no RtoObj in Spanish is because there is no Tdef in this language. Epistemic verbs select a regular clause structure.

6. Conclusions

This study has shown that code-switching can be used to provide evidence for or against existing theoretical proposals. This particular study investigated the possible grammatical factors that give rise to RtoObj. We pointed out that the crux could be found either in a feature of the matrix clause—by hypothesis, associated with little

v—or with a feature of the subordinate clause—a feature in T that makes it transparent for external probes. By using code-switching, we were able to limit the scope of our search for the necessary properties that give rise to RtoObj, a search that now is restricted to the infinitival complement. At this point, two options were presented: one that requires a stipulation that epistemic verbs such as ‘think’ and ‘consider’ do not select for Tdef and one that proposes an absence of T

def in Spanish altogether, following

Ausín’s (

2001) analysis of the RtoSubj verb

parecer. We tentatively adopt the second option because it seems to provide a more parsimonious understanding of Spanish syntax. Further study is needed to corroborate this analysis, including a potential avenue via a code-switching study of Raising to Subject.

The subjects that participated in the study were described as “deep bilinguals”, that is, people who acquired both languages since birth or early childhood and who have been able to develop both languages into adulthood. A reviewer for

Languages wonders about the generalizability of our results, given that the participants are heritage speakers. The grammars of heritage speakers indeed diverge from those of monolingual speakers in all kinds of interesting ways (see

Polinsky and Scontras 2020 for an overview), which can indeed pose challenges for generalizability. However, we think that our result can be generalized beyond this particular group of subjects on the grounds of existing asymmetries between English and Spanish with respect to Raising. As mentioned above, we have argued that the code-switching experiment shows that the feature that is responsible for the absence of RtoObj in the Spanish of our bilingual subjects must be found in the subordinate clause—be it a TdefP or a

vP. It could be the case that the rejection of RtoObj among monolingual speakers is due to something else—such as the matrix

v. Or it could also be that both the matrix

v and the subordinate TdefP or

vP contribute to the rejection of RtoObj among monolingual Spanish speakers but not among the bilingual ones. However, a sensible application of the Ockam’s Razor heuristic leads us to think that these scenarios are less plausible than the one presented in these pages.