Bailando, me paso el día bailando y los vecinos mientras tanto no paran de molestar. Parar de + inf as an Interruptive Verbal Periphrasis in Spanish

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Paró de cenar porque se le hacía tarde para ir al teatro.‘He/she stopped having dinner because he/she would be late for the theatre.’

- (2)

- Por fin ha parado de llorar.‘He/she has finally stopped crying.’

- (3)

- Acabó de cenar a tiempo para ir al teatro.‘He/she ended her dinner in time to go to the theatre.’

- (4)

- ?Ahora ha acabado de llorar.‘He/she has just now ended his/her crying.’

- (5)

- ¿Qué? ¿Ya has acabado de llorar?‘What? Have you stopped crying yet?’

2. What Do We Know about the parar de + inf Construction?

- (6)

- El tronco en la chimenea no para de arder. (Olbertz 1998, p. 110)‘The log in the fireplace does not stop burning.’

- (7)

- *Le hacían tantos encargos que parecía que nunca iban a parar de eso. (Olbertz 1998, p. 111)

se usa preferentemente cuando se quiere transmitir la idea de que el evento verbal no va a volver a reanudarse. Por el contrario, cuando puede haber alguna posibilidad de que el evento prosiga más adelante, la perífrasis que suele elegirse es <dejar de + inf> .

‘is preferred when wishing to convey the idea that the verbal event will not resume. In contrast, when the possibility exists that the event will continue sometime in the future, the choice of verbal periphrasis tends to be <dejar de + inf>.’

- (8)

- Cuando dejaba de nevar, salían las máquinas quitanieves.‘When it stopped snowing, the snowploughs came out.’

- (9)

- Cuando paraba de nevar, salían las máquinas quitanieves.‘When it stopped snowing, the snowploughs would come out.’

Si bien <dejar de + VInfinitivo>, al igual que <parar/cesar de + VInfinitivo>, denota el abandono (interrupción) del camino antes de llegar a la meta, creemos que las perífrasis <parar/cesar de + VInfinitivo> añaden algún matiz a la manera en cómo se lleva a cabo dicha interrupción: en este caso, el empleo de una dinámica de fuerza (df) más intensa que la que se utiliza en la perífrasis <dejar de + VInfinitivo>.

‘Although <dejar de + VInfinitive>, like <parar/cesar de + VInfinitive>, denotes the act of leaving (interrupting) the path before arriving at the goal, we believe that the verbal periphrases <parar/cesar de + VInfinitive> add a further nuance in meaning as to the way in which said interruption has been effectuated: in this case, the use of a force dynamic (fd) that is greater than that used in the verbal periphrases <dejar de + VInfinitive>.’

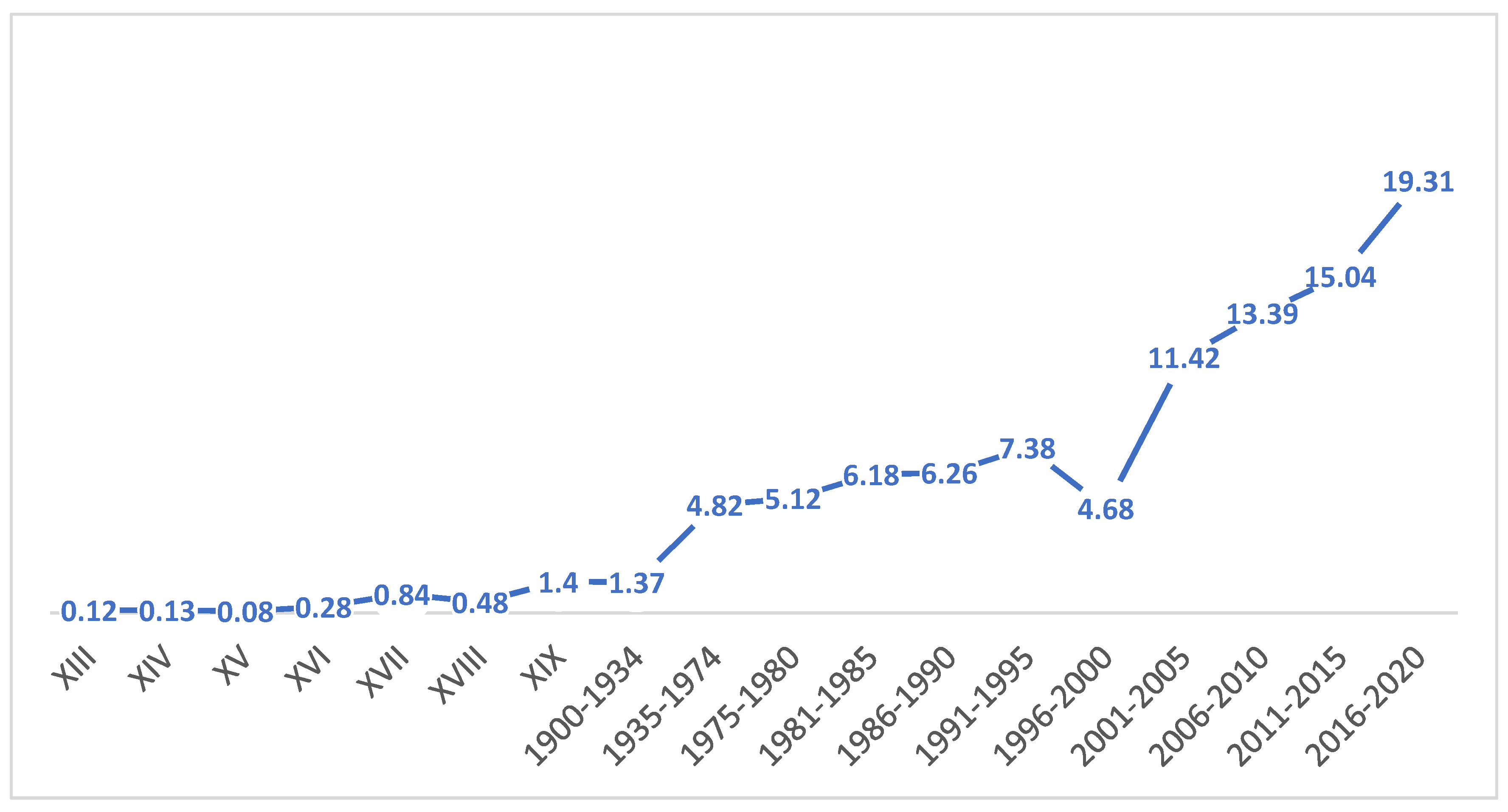

3. Parar de + inf, a Verbal Periphrasis of Contemporary Language

- (10)

- DaylicaYa deja de ser tan lindo conmigo.‘Come on stop being so nice to me.’AldrichCuando tú pares de serlo conmigo. Te quiero puerquita. (Twitter, 14 September 2020)‘[only] when you stop [being nice] to me. I love you my little piglet.’

- (11)

- porfa puede Shein parar de enamorarme de todos los vestidos que tiene. (Twitter, 27 April 2021, 11:53 p.m.)‘please Shein stop making me fall in love with all the dresses you have.’

- (12)

- “Tourist, go home”, “Gaudí hates you” or “Parad de destrozar nuestras vidas” ‘Stop ruining our lives’.Estos son algunos de los mensajes que se encuentran muchos visitantes extranjeros pintados en las fachadas de algunos barrios de Barcelona, en España. (“El turismo no es bueno en todos lados”. Available online: http://castillosenlinea.blogspot.com/2017/06/el-turismo-no-es-bueno-en-todos.html (accessed on 8 May 2021))

- (13)

- rrrrosalía@nidepuntillasno puedo parar de ser una persona súper feliz en sant jordi. (Twitter, 23 April 2021)‘I can’t stop feeling so happy on San Jordi.’

4. Parar de + inf in the Perspective of Construction Grammar

4.1. Parar de + inf As an Interruptive Verbal Periphrasis

- (14)

- -¡Ya paren de discutir que son casi las ocho! —gritó con su voz de pajarraco. (Isaac Goldemberg, El nombre del padre, Perú, 2001, corpes xxi)‘“Stop arguing now, it’s almost eight!” He yelled with his ugly bird voice.’

- (15)

- Estoy seguro de que Isabel se encontró con él para decirle que pare de molestar. (Marcelo Birmajer, Historia de una mujer, Argentina, 2007, corpes xxi)‘I am sure that Isabel met with him to tell him to stop bothering her.’

- (16)

- En la cocina, Leocadia paró de cortar. (Cristina Sánchez-Andrade, Bueyes y rosas dormían, España, 2001, corpes xxi)‘In the kitchen, Leocadia stopped cutting.’

- (17)

- Ibai@IbaiLlanosSi tenéis que estudiar por qué cojones estáis en Twitter podéis ser responsables por favor.

- (18)

- a. Dejó de hablarme en cuanto supo que yo no le iba a votar.‘He stopped speaking to me when he found out I wasn’t going to vote for him.’b. ?Paró de hablarme en cuanto supo que yo no le iba a votar.‘He stopped talking to me when he knew I wasn’t going to vote for him.’c. Solo paró de hablar cuando se lo supliqué.‘He only stopped talking when I begged him [to stop].’d. Dejó de hablar cuando acabó su charla.‘He/she stopped speaking when he/she ended his/her talk.’e. Paró de hablar cuando acabó su charla.‘He/she stopped talking when he/she ended his/her talk.’

- (19)

- MaRiA cAnDeL@mariacandel05Quiero parar de ser dislexica (sic) dios dios dioss aaaaa. (Twitter, 23 April 2021)‘I want to stop being dyslexic god god godddd aaaaaa.’

- (20)

- Durante 73 segundos el mundo tuvo que esperar que Obdulio parara de hablar con dos británicos en su castellano estragado en suburbios montevideanos y devolviera el balón. (Jorge Valdano, El miedo escénico y otras hiervas, Argentina, 2002, corpes xxi)

- (21)

- Yo creo que Aznar ya va//ya va a parar de salir en la tele y en todas esas partes/ahora/nos va/eeh vamos a ver mucho a Rajoy. (Corales, La ventana: la tertulia de los niños, 30.October.2003, Cadena Ser, corpes xxi)

- (22)

- a. Paró de estudiar para ponerse a trabajar.‘He stopped studying to work.’b. Dejó de estudiar para ponerse a trabajar.‘He abandoned studying to work.’

- (23)

- a. Tengo que pensar en todo eso. Tengo muchas dudas. Tal vez pare de estudiar. (Rodrigo Rey Rosa, Carta de un ateo guatemalteco al Santo Padre, Guatemala, 2020, corpes xxi)

- (24)

- El riesgo de desarrollar un cáncer siempre disminuye si se para de fumar, dice Jorge García. (La voz de Galicia 17.04.2016. Available online: https://www.lavozdegalicia.es/noticia/extravozok/2016/04/17/esperas-dejar-tabaco/0003_201604SO17P2991.htm (accessed on 8 May 2021))‘The risk of developing cancer always decreases if you stop smoking.’

- (25)

- No podía parar de reír.‘He/she couldn’t stop laughing.’

- (26)

- ¿Quieres parar de llorar?‘Do you want to stop crying?’

- (27)

- a. ¿Algún día pararás de fumar? (Si es que fumas). (Twitter, 7 April 2015)‘One day will you stop smoking? (If you do smoke).’

- (28)

- Ilan sonríe y se va. Los soldados le esperan. Las plumas paran de caer. (Aurora Mateos, El suicidio del ángel, España, 2006, corpes xxi)‘Ilan smiles and leaves. The soldiers wait. The feathers stop falling.’

- (29)

- Te prestaría algo, no voy a mojar mis prendas porque sí, espera a que pare de llover. (Isaura Contreras, La casa al fin de los días, México 2007, corpes xxi)

4.2. Parar de + inf As a Verbal Periphrasis Expressing Repetition or Continuity

- (30)

- a. Llevo todo el día sin parar de pensar en esto. (Twitter, 22 April 2021)‘All day long I have not stopped thinking about this.’b. @NicolasLemesÉl no paraba un momento de recordar sus labios. (Twitter, 28 December 2016)‘He did not stop for one moment recalling her lips.’

- (31)

- Ya cállate, Mica. Nomás despiertas y no paras de hablar. (Silvia Peláez, Acorazados, México, 2008, corpes xxi)‘Shut up, Mica. You wake up and don’t stop talking.’

- (32)

- Yo es que tengo la negra. No paro de tener accidentes. (Francisco Nieva, El Cíclope, España, 2009, corpes xxi)‘I have the black [a jinx]. I don’t stop having accidents.’

- (33)

- No sabemos nada. Y sin embargo no paramos de escribir. (Miguel Ángel Hernández, No (ha) lugar, España, 2007, corpes xxi)‘We don’t know anything. And still, we do not stop writing.’

- (34)

- Pero los habitantes de Leningrado no han parado de sufrir esa situación desde que fue cercada en otoño. (Jorge M. Reverte, La división azul. Rusia 1941–1944, España, 2011, corpes xxi)

- (35)

- (…) no paramos de correr hasta que llegamos a Postrer Valle. (Juan Ignacio Siles del Valle, Los últimos días del Che, Bolivia, 2007, corpes xxi)‘(…) we did not stop running until we arrived at Postrer Valle.’

- (36)

- Contigo nada es serio, nena. ¿No ves que casi causas un desastre? Y encima no paras de reírte. (Amaya Ascuncé, En la cocina con la drama mamá. El libro de recetas que no conseguí escribir, España, 2013, corpes xxi)

- (37)

- Los mensajes privados de Greenfluencers están “colapsados”, según Burque. “No paramos de recibir mensajes de gente que nos pide consejos para cuidar sus plantas”. (Emilio Sánchez Hidalgo, Verne. El país, España 2019, corpes xxi)

- (38)

- Tras observar el vídeo, los reporteros, que nos visitan en esta ocasión de Miss Universo, no pararon de aplaudir, pues quedaron fascinados con la riqueza de esta nación. (La hora, 2004, Ecuador, corpes xxi)

- (39)

- Al año siguiente, el entonces presidente azulgrana Joan Laporta le entregó las riendas del primer equipo y, desde los dos primeros sustos en la Liga, Guardiola no ha parado de dar alegrías a los barcelonistas tras acumular victorias y títulos. (Anonymous, Sport.es, España, 2010, corpes xxi)

- (40)

- a. No podía parar de pensar y de desearle lo peor. (Alejandro López, La asesina de Lady Di, Argentina, 2001, corpes xx)‘He/she could not stop thinking and wishing the worst for him/her.’

- (41)

- SIRENA. ¿Podés parar de mover los brazos?... ¡Me mareás! (Liliana Heker, La crueldad de la vida, Argentina, 2001, corpes xx)‘SIRENA: Could you stop moving your arms? You’re making me dizzy!’

- (42)

- Debemos parar de darnos palmaditas cuando esporádicamente alguno de nuestros deportistas tenga una buena figuración. (Alejandro Bermúdez, El tiempo, Colombia, 2009, corpes xxi)

- (43)

- Dice Calamaro: ¿Es razonable querer parar de hacer el amor? (Toni Segarra, Desde el otro lado del escaparate, España, 2009)‘Calamaro says: Is it reasonable to want to stop making love?’

- (44)

- No quiero parar de estudiar. (Sarai Cabral, El universal, México, 2011, corpes xxi)‘I don’t want to stop studying.’

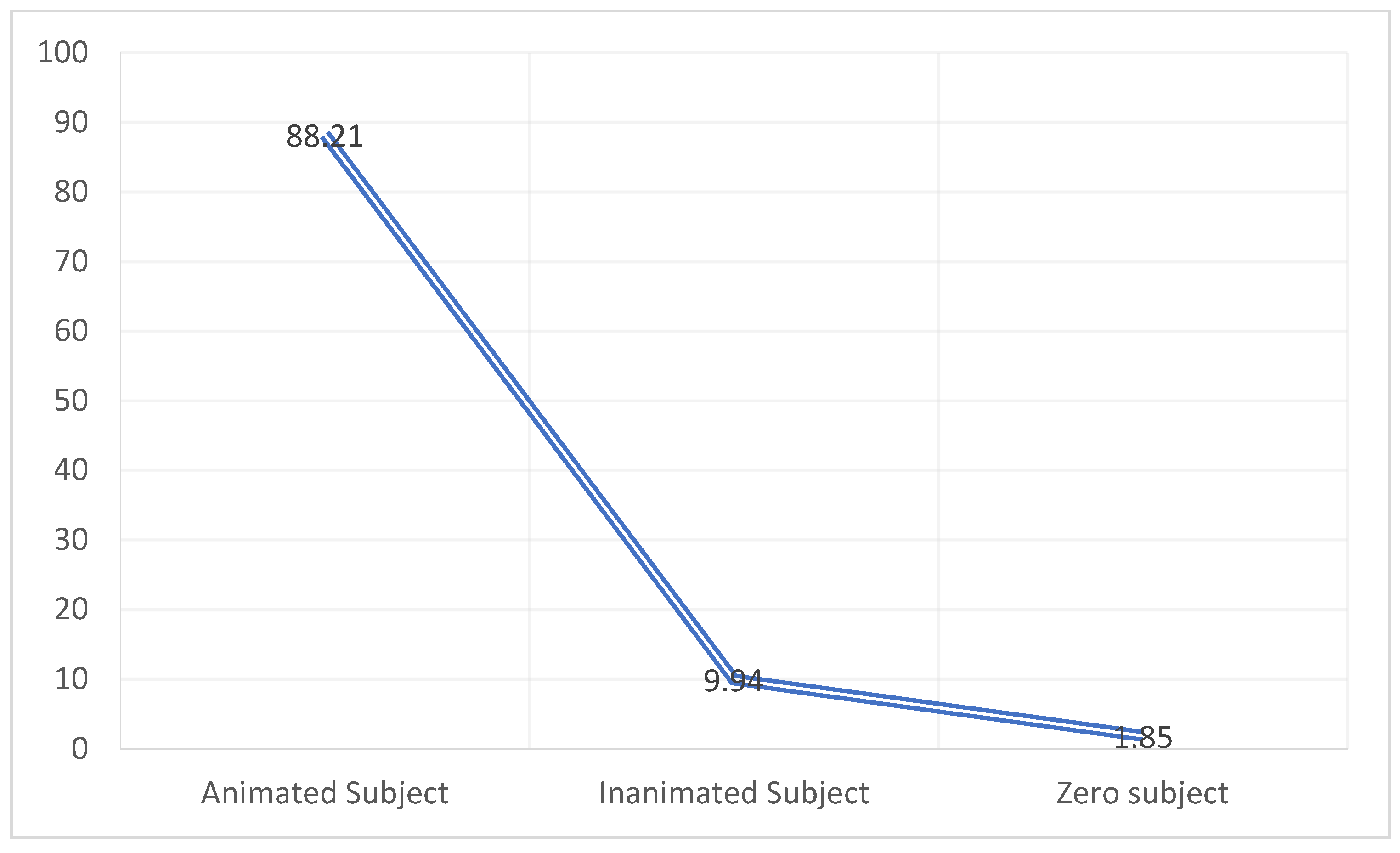

4.3. Verbal Forms Associated with the Infinitive in Parar de + inf Constructions

- (45)

- Para de ser tan pesado, niño.‘Stop being such a pest, boy.’

- (46)

- Para de estar nervioso.‘Stop being nervous.’

- (47)

- Se para de vivir cuando se para de leer. (https://www.diariodenavarra.es/participacion/cartasaldirector/contenidos/se-para-vivir-cuando-para-leer-8085-109.html (accessed on 8 May 2021))‘One stops living when they stop reading.’

- (48)

- No puedo parar de ser yo misma.‘I can’t stop being myself.’

- (49)

- No puedo parar de entrar y salir.‘I can’t stop entering and leaving.’

- (50)

- ?A ver cuándo paras de vivir con tu madre.‘Let’s see when you stop living with your mother.’

- (51)

- ?No para de morir.‘He/she can’t stop dying.’

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Suplemento is used in some Spanish functional grammar approaches to refer to adverbial complements. |

| 2 | The concept of force dynamics was coined by Talmy (1988, 2000). According to this author, the experience of humans in their environment can be applied to language and cognition. Thus, the physical experience of forces that are required in order to cause a particular action can be mapped onto the cognitive plane and used to express different concepts. The force dynamics model involves some participants (those who exert forces and others in charge of containing it), tendencies in terms of force (referring to movement or rest) and the equilibrium of forces (the entity exerting the greatest force tips the balance in its favour), and a resulting interaction of forces (which is translated into movement or keeping the entity at rest and means that some entities are successful and others fail). In the case of the verbal periphrasis parar de + inf in its interruptive sense, the subject of the predicate exerts a force in order to detain the event expressed by the infinitive. This force uses energy. |

| 3 | We use the concept of communicative proximity in keeping with the theoretical considerations of Koch and Oesterreicher (1990/2007), who opt for a characterisation of communicative situations in terms of a continuum ranging from genres typically associated with communicative proximity or immediacy (e.g., a colloquial conversation) to others where greater communicative distance prevails (e.g., legal texts). |

| 4 | Our use of the concept of grammatical construction is the same as that used in the field of construction grammar. Here, a grammatical construction is a conventionalised pattern that relates a form with a particular meaning. Constructions are much more than a combination of words: a construction is a clause or syntactic phrase just like a word or morpheme. Furthermore, constructions are formulated at different levels of abstraction. Thus, there are constructions that are maximally saturated, such as Salomé hizo matar a Juan (‘Salome had Juan killed’), and others that are maximally schematic (e.g., causative constructions (X verb Y Z ‘X makes Y do Z’)). Between the schematic causative construction and the one explicitly formulated with words, one can find others that are more or less saturated, such as ‘X had Y killed’ or ‘X made Y inf’. For more information, see Goldberg (1995) and Goldberg and Casenhiser (2006), and for Spanish, see Gras Manzano (2011) and Garachana (2021). |

| 5 | As one of the reviewers points out, both of the constructions share an important dose of expressivity. |

References

- Aparicio Mera, Juan. 2016. Representación computacional de las perífrasis de fase: De la cognición a la computación. Barcelona: Universidad de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo Martín, Ana, and Luis García Fernández. 2016. Perífrasis verbales. In Enciclopedia lingüística hispánica, vol. I. Edited by Javier Gutiérrez-Rexach. Londres: Routledge, pp. 785–96. [Google Scholar]

- Camus Bergareche, Mario. 2006. Parar de + infinitivo. In Diccionario de perífrasis verbales. Edited by Luis García Fernández. Madrid: Gredos, pp. 206–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cornillie, Bert, Giulia Mazzola, and Miriam Thegel. 2021. Las Tradiciones Discursivas en tiempos de lingüística cuantitativa: ¿corrección epistemológica o deconstrucción metodológica? Leuven: K.U. Leuven. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Castro, Félix. 1999. Las perífrasis verbales en el español actual. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Garachana, Mar. n.d. Evolución de las verbales interruptivas en español. Dejar de + INF, Parar de + INF y Cesar de + INF. In Construcciones Verbales Aspectuales. Precedentes Latinos y diacronía en español de las Construcciones Fasales. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Garachana, Mar. 2008. En los límites de la gramaticalización. La evolución de encima (de que) como marcador del discurso. Revista de Filología Española 88: 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garachana, Mar. 2021. Gramática de construcciones. In Sintaxis del español/The Routledge Handbook of Spanish Syntax. Edited by Guillermo Rojo, María Victoria Vázquez and Rena Torres. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- García, Erica. 1967. Auxiliaries and the criterion of simplicity. Language 43: 853–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Fernández, L. 2006. Diccioinario de perífrasis verbales. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Adele. 1995. Constructions: A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Adele, and Devin Casenhiser. 2006. English Constructions. In Handbook of English Linguistics. Londres: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 343–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Manzano, Pilar. 1992. Perífrasis verbales con infinitivo. Madrid: UNAM. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Torrego, Leonardo. 1988. Perífrasis verbales. Sintaxis, semántica y estilística. Madrid: Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Torrego, Leonardo. 1999. Los verbos auxiliares. Las perífrasis verbales de infinitivo. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, pp. 3323–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gras Manzano, Pedro. 2011. Gramática de Construcciones en Interacción. Propuesta de un modelo y aplicación al análisis de estructuras independientes con marcas de subordinación en español. PhD. Barcelona: University of Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Havu, Jukka. 2011. La evolución de la perífrasis del pasado reciente acabar de + infinitivo. In Estudios sobre perífrasis y aspecto. München: Peniope, pp. 158–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul. 1991. On some Principles of Grammaticalization. In Approaches to Grammaticalization, Vol. 1. Edited by Elizabeth Closs Traugott and Bernd Heine. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub Co, pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kabatek, Johannes. 2013. ¿Es posible una lingüística histórica basada en un corpus representativo? Iberoromania 77: 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, Peter, and Wulf Oesterreicher. 1990/2007. Lengua Hablada en la Romania: Español, francés, italiano, 2nd ed. de la versión española de Araceli López Serena. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Laca, Brenda. 2002. Spanish «aspectual» periphrases: Ordering constraints and the distinction between situation and viewpoint aspect. In From Words to Discourse: Trends in Spanish Semantics and Pragmatics. Edited by J. Gutiérrez-Rexach. Amsterdam-Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 61–93. [Google Scholar]

- Morera, Marcial. 1991. Diccionario crítico de las perífrasis verbales del español. Fuerteventura: Servicio de Publicaciones del Cabildo Insular de Fuerteventura. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española and Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Español. 2009. Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa. [Google Scholar]

- Olbertz, Hella. 1998. Verbal Periphrases in a Functional Grammar of Spanish. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Carlota. 1991. The Parameter of Aspect. Dordrech Boston-Londres: Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Talmy, Leonard. 1988. Force dynamics in language and cognition. Cognitive Science 12: 49–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmy, Leonard. 2000. Towards a Cognitive Semantics I: Concept Structuring Systems. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

| Country | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Affirmative | Negative | |

| Argentina | (38/386) 9.8% | (348/386) 90.15% |

| Bolivia | (3/52) 5.76% | (49/52) 94.23% |

| Chile | (19/176) 10.79% | (159/176) 89.20% |

| Colombia | (39/314) 12.42% | (275/314) 87.57% |

| Costa Rica | (6/23) 26.08% | (17/23) 73.91% |

| Cuba | (7/84) 8.33% | (77/84) 91.66% |

| Ecuador | (5/76) 6.57% | (71/76) 93.42% |

| El Salvador | (1/36) 2.77% | (35/36) 97.22% |

| Spain | (89/1936) 4.59% | (1847/1936) 95.40% |

| USA | (4/20) 20% | (16/20) 80% |

| Guatemala | (6/36) 16.66% | (30/36) 83.33% |

| Equatorial Guinea | (1/21) 4.76% | (20/21) 95.23% |

| Honduras | (6/48) 12.5% | (42/48) 87.5% |

| Mexico | (23/253) 9.09% | (230/253) 90.9% |

| Nicaragua | (11/31) 35.48% | (20/31) 64.51% |

| Panama | (0/11) 0% | (11/11) 100% |

| Paraguay | (7/49) 14.28% | (42/49) 85.71% |

| Peru | (4/104) 3.84% | (100/104) 96.15% |

| Puerto Rico | (5/35) 14.28% | (30/35) 85.71% |

| Dominican Republic | (4/38) 10.52% | (34/38) 89.47% |

| Uruguay | (7/85) 8.23% | (78/85) 91.76% |

| Venezuela | (10/110) 9.09% | (100/110) 90.90% |

| Total | (295/3924) 7.51% | (3629/3924) 92.48% |

| Polarity | DEBER ‘must’ | Hacer (‘do’) Causative Value | Hay Que (‘need to/must’) | Ir a (‘go’) | (‘Manage’) | Poder (‘can’) | QUERER (‘want’) | Saber (‘know’) | Tener Que (‘have to’) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 6 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Negative | 3 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 103 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Total | 9 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 109 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Verb | Absolute Frequency | Frequency per Million Words | Aktionsart |

|---|---|---|---|

| hablar (‘to talk’) | 361 | 9.1 | activity |

| llorar (‘to cry’) | 244 | 6.15 | activity |

| reír (‘to laugh’) | 234 | 5.89 | activity |

| hacer (‘to do’) | 138 | 3.47 | activity |

| dar (giros que significan molestar) (‘to turn out, creating an annoyance’) | 125 | 3.15 | activity |

| crecer (‘to grow’) | 113 | 2.84 | activity |

| llover (‘to rain’) | 93 | 2.34 | activity |

| mover (‘to move’) | 85 | 2.14 | activity |

| mirar (‘to look’) | 77 | 1.94 | activity |

| trabajar (‘to work’) | 71 | 1.78 | activity |

| sonar (‘to ring’) | 67 | 1.68 | activity |

| decir (‘to say’) | 65 | 1.63 | activity |

| gritar (‘to yell’) | 56 | 1.41 | activity |

| comer (‘to eat’) | 56 | 1.41 | activity/accomplishment |

| pensar (‘to think’) | 54 | 1.36 | activity |

| correr (‘to run’) | 50 | 1.26 | activity |

| preguntar (‘to ask’) | 47 | 1.18 | accomplisment |

| tocar (instrumentos) (‘to play an instrument’) | 40 | 1 | activity |

| bailar (‘to dance’) | 41 | 1 | activity |

| repetir (‘to repeat’) | 36 | 0.9 | activity |

| sonreír (‘to smile’) | 34 | 0.85 | activity |

| beber (‘to drink’) | 32 | 0.8 | accomplishment |

| escribir (‘to write’) | 32 | 0.8 | accomplishment |

| llamar (‘to call’) | 30 | 0.75 | activity |

| llegar (‘to arrive’) | 26 | 0.65 | accomplishment |

| leer (‘to read’) | 24 | 0.6 | accomplishment |

| toser (‘to cough’) | 22 | 0.554575 | repeated achievement |

| tomar (beber, tomar fotos, tomar el pelo) (‘to drink’, ‘to take photos’, ‘to pull someone’s leg’) | 21 | 0.529367 | activity |

| fumar (‘to smoke’) | 21 | 0.52 | activity |

| quejarse (‘to complain’) | 20 | 0.504159 | activity |

| subir (‘to go up’) | 20 | 0.504159 | accomplishment |

| temblar (‘to tremble’) | 19 | 0.478951 | activity |

| jugar (‘to play’) | 19 | 0.47 | activity |

| recibir (‘to receive’) | 18 | 0.453743 | achievement |

| salir (‘to go out’) | 18 | 0.453743 | achievement |

| entrar (‘to come in’) | 18 | 0.45 | achievement |

| besar (‘to kiss’) | 16 | 0.403327 | activity |

| buscar (‘to look for’) | 16 | 0.403327 | activity |

| aumentar (‘to increase’) | 16 | 0.4 | activity |

| discutir (‘to argue’) | 16 | 0.4 | activity |

| saltar (‘to jump’) | 15 | 0.378119 | achievement |

| meter (‘to put’) | 15 | 0.378119 | achievement |

| cantar (‘to sing’) | 14 | 0.35 | activity |

| remover (‘to stir’) | 13 | 0.327704 | activity |

| sangrar (‘to bleed’) | 13 | 0.327704 | activity |

| viajar (‘to travel’) | 13 | 0.327704 | activity |

| ladrar (‘to bark’) | 13 | 0.327704 | activity |

| caer (‘to fall’) | 13 | 0.32 | achievement |

| sufrir (‘to suffer’) | 12 | 0.302496 | state |

| imaginar (‘to imagine’) | 12 | 0.302496 | activity |

| lanzar (‘to throw’) | 12 | 0.302496 | achievement |

| pedir (‘to ask for something’) | 12 | 0.302496 | achievement |

| sacar (‘to remove’) | 12 | 0.302496 | achievement |

| recordar (‘to remember’) | 11 | 0.277288 | state/achievement |

| ver (‘to see’) | 11 | 0.277288 | state |

| rascarse (‘to scratch oneself’) | 10 | 0.25208 | activity |

| rezar (‘to pray’) | 10 | 0.25208 | activity |

| vomitar (‘to vomit’) | 10 | 0.25208 | activity |

| saludar (‘to greet/to wave to someone’) | 10 | 0.25208 | activity |

| girar (‘to turn’) | 10 | 0.25 | activity |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garachana, M. Bailando, me paso el día bailando y los vecinos mientras tanto no paran de molestar. Parar de + inf as an Interruptive Verbal Periphrasis in Spanish. Languages 2021, 6, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040171

Garachana M. Bailando, me paso el día bailando y los vecinos mientras tanto no paran de molestar. Parar de + inf as an Interruptive Verbal Periphrasis in Spanish. Languages. 2021; 6(4):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040171

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarachana, Mar. 2021. "Bailando, me paso el día bailando y los vecinos mientras tanto no paran de molestar. Parar de + inf as an Interruptive Verbal Periphrasis in Spanish" Languages 6, no. 4: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040171

APA StyleGarachana, M. (2021). Bailando, me paso el día bailando y los vecinos mientras tanto no paran de molestar. Parar de + inf as an Interruptive Verbal Periphrasis in Spanish. Languages, 6(4), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040171