Monitoring 21st-Century Real-Time Language Change in Spanish Youth Speech

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1. RE2F7: pues me lié con un chaval ¿no? y ahí negro to’ guapo tía yo qué sé súper majo y con mucha labia ¿sabes? y y me enamoré tía me enamoré que flipas

(‘well I hooked up with a guy no? and he was black really handsome girl I don’t know super nice and with a lot of lip you know? and and I fell in love with him girl I fell in love like crazy’)(CORMA: RE_AM2_F_03)4

2. General Background Information on the Observed Phenomena

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Corpus Data

3.2. Parameters of (Recent) Language Change

4. Monitoring Recent Language Change within the Intensifier Paradigm

4.1. General Overview

4.2. Configuration of the Paradigms

4.3. Stability and Shifts within the Paradigms

2. IR2F20: eee—es una hija de puta(‘yeah she’s a son of a bitch’)

IR2F19: mazo (‘really’)(CORMA: IR_AM2_F_09)

3. MALCC2J01: ya pero que tenía que estudiar(‘yeah but I had to study’)

MALCC2J03: has estudiado mucho estos días(‘you’ve been studying a lot these days’)

MALCC2J01: al final no he estado toda fumada(‘in the end no, I was completely/very stoned’)

MALCC2J03: de porros (‘of joints’)(COLAm: malcc2-14)23

4. RE2F3: pensaba que iba a decir <¿pero eres Claudia?>(‘I thought he was going to say <but are you Claudia?>’)

RE2M2: ¿eres Claudia o el (())?(‘are you Claudia or the (())?’)

RE2M1: ostia sería to’ to’ cringe (‘fuck it would be really really cringe’)(CORMA: RE_AM2_02)

5. Monitoring Recent Language Change within the Vocative Paradigm

5.1. General Overview

5.2. Configuration of the Paradigms

5. IR2F16: (drinks water, chokes and coughs loudly)

IR2F17: hostia tía puta tragona trágatelo yaa (both laugh) (‘damn girl fucking gannet swallow it now’)(CORMA: IR_AM2_F_08)

6. MS2F4: pero escúchame a mí nos ha jodido la vida el año pasado y este(‘but listen to me he fucked our lives last year and this year’)

MS2F3: a mí a mí sí (()) (())(‘mine mine yes (unintelligible)’)

MS2M7: y este porque tenemos eh hay una desnivel monumental(‘and this year because we have uh there is a huge discrepancy’)

MS2F3: eh guapos a mí también ¿vale?(‘eh beautiful people mine too right?’)

MS2M7: ya maja pero tú primero bachillerato ya vas a ir con un buen nivel a segundo (‘right pretty but you the first year in high school you will already go with a good level to the second year’)(CORMA: MS_AM2_03)

5.3. Stability and Shifts within the Paradigms

7. IR2F25: e-el día de su cumple le dijo esta ah ay dios eh felicidades no sé qué y este se empezó a quejar de que la gente era mazo falsa que le decían-le decía cosas-o sea eso-tío y que se le puso a Carmen eh (‘th- the day of his birthday she told him she ah oh god uh congratulations whatever and he began to complain that people are so false and that they told him- he told her things- that is that- dude and that he wrote to Carmen uh-’)(CORMA: IR_AM2_F_11)

8. MALCC2G02: joder qué frío tronco (‘damn it’s so cold dude’)(COLAm: malcc2-03)

9. MALCC2J03: di di rin ti ti ti

MALCC2G02: voy a fumar allí tron(‘I go smoke over there dude’)

MALCC2J01: y yo chaval (‘me too boy’)(COLAm: malcc2-03)

10. IR2M4: es que tío es que tío es que de verdad Dani mírate lo del partido que te lo del grupo que te he dicho, anda qué falso tú qué falso qué falso qué falsedad tú aaaa qué risa vete a ajustes de grupo (‘it is dude it is dude it is really Dani look to that of the game that you that of the group that I told you, come on how fake you how fake how fake what a lie you aaaa that’s so funny go to group settings’)(CORMA: IR_AM2_M_02)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Intensifiers TYPE | Literal Translation | Idiomatic Translation |

| adefesio | hideous | butt-ugly |

| asco | nausea | disgusting |

| -azo | huge, massive | nice, great |

| bien | well | really |

| cacho | piece, slice | bloody |

| castaña | chestnut | annoying |

| como un enano | like a dwarf | a lot |

| coñazo | big pussy | a pain in the ass |

| de puta madre | mother i like to fuck/milf | fucking great |

| del culo | from the head to the ass | really, absolutely |

| hostia | communion waffer | awful, amazing |

| huevo | egg | a lot, as shit |

| -ísimo | very | very, really |

| jodido | messed up | fucking |

| más | more | really |

| mazo | big hammer | really, a lot |

| menudo | small | what a… |

| mierda | shit | shitty |

| mogollón | a lot | a shitload, loads |

| montón | a pile | a lot |

| -ón | big, large | awful, nice |

| -ote | big, large | huge |

| pimiento | pepper | a damn |

| puñetero | annoying | bloody |

| puto | whore | fucking |

| que (lo) flipas | that freaks you out, like crazy | extremely |

| que te cagas | that you shit yourself | extremely, very well |

| super- | super | super |

| to(do) | whole | very |

| tope | limit | very, really |

| Vocatives TYPE | Literal Translation | Idiomatic Translation |

| aventado | brave | brave |

| cabrón | male goat | bastard |

| capulla | cocoon | prick, stupid, idiot |

| cariño | darling | darling |

| cerda | sow | dirty woman, slut |

| cerda marrana | sow sow | dirty woman, slut |

| chaval/chavala | boy/girl | lad/lass |

| che | hey, listen | hey, listen |

| chico/chica | boy/girl | kid/girl |

| chino | Chinese | fool, strange |

| chulo | cool, pimp | cool, pimp, dude |

| colega | colleague | buddy |

| coño | pussy | pussy, fuck |

| gilipollas | asshole | asshole |

| gorrina | piglet | piglet, dirty |

| guapos | beautiful people | beautiful people |

| hermano | brother | bro |

| hijo/hija | son/daughter | kid/girl |

| hijo/hija de puta | son/daughter of a bitch | son/daughter of a bitch |

| hombre | man | man, dude |

| idiota | idiot | idiot |

| imbécil | stupid idiot | stupid idiot, moron |

| jai | attractive young woman | hottie, chick |

| joven | young | young |

| loco | crazy | crazy |

| macho | male animal | buddy, masculine man |

| machote | big male animal | buddy, very masculine man |

| majo/maja | pretty | friendly |

| muchacho de marca | boy of style | snob |

| negro | black person | nigga, dark skinned person |

| nena | girl | girl, baby |

| niño | boy | boy |

| panzón | potbelly | potbelly |

| payaso | clown | clown |

| pedazo subnormal | subnormal piece | stupid |

| pirula | dick | dick |

| pobre | poor | poor thing |

| pobrecito | little poor | little poor thing |

| primo | nephew, cousin | buddy, dude |

| puta ameba | fucking ameba | fucking idiot |

| puta tragona | fucking gannet, greedy | fucking gannet, greedy |

| señores | gentlemen | gentlemen |

| tío/tía | uncle/aunt | dude/girl |

| tolai | foolish, incredulous | foolish, incredulous |

| tonto/tonta | fool, silly | fool, silly |

| toro | bull | man |

| tronco/tronca/tron | trunk | dude/girl |

| tú | you | you |

| 1 | See also the role of Madrid’s youth, and in particular, la Movida Madrileña in the years after Franco’s death (e.g., (Algaba Pérez 2020)). |

| 2 | In this paper, the concept of ‘teen language’ is defined as the language spoken by teenagers between 12 years (the start of adolescence) and 18 years (when adolescents become legally major in most countries) (Eisenstein 2005). |

| 3 | It goes without saying that both phenomena are situated at the interface with syntax and pragmatics, but in this study we are mostly interested in their use as lexical strategies. |

| 4 | Example taken from the Corpus Oral de Madrid (CORMA) (cf. Section 3). Each speaker received a codified name according to different variables. The initial letters refer to the communicative context (e.g., AM = amigos (‘friends’), PEL = peluquería (‘hair salon’)) or the educational institution where the teenagers were recruited (e.g., in this case RE). The first number gives more information about the generation to which the speaker belongs (e.g., 2 = Gen2: 12–25 y; 3 = Gen3: 26–55 y; for more details, see Section 3). The following letter informs about the gender (e.g., M = male, F = female) and the last number (e.g., 7 in RE2F7) indicates that the speaker was the seventh female speaker of the second generation of her specific school to participate in the recordings. |

| 5 | Rodríguez González (2002, pp. 47–48) refers to the obsolescence of certain terms of address under specific sociopolitical circumstances, especially those expressing deference such as don (‘sir’), which are substituted by other, more informal terms of address, such as the second person pronoun tú (at the expense of formal usted) and the nominal terms amiga (‘friend’), mujer (‘woman’), and compañera (‘colleague, buddy’). |

| 6 | It is noteworthy that, from a generational viewpoint, the participants from COLAm are (late) Millennials, born between 1980 and 1996, while the youngsters from CORMA belong to Generation Z, born between 1996 and today (Dimock 2019). This implies that the data under analysis document a generational shift. |

| 7 | The concept of intensifiers often embraces all expressions of degree modification, both scaling upwards and downwards from an assumed norm (Quirk et al. 1985). In this study, we only considered intensifiers that increase the degree or expressive power of the modified item. |

| 8 | Note that the scope is not restricted to cases in which the modified element is an adjective (i.a. (Aijmer 2018; Bauer and Bauer 2002; Lorenz 2002; Tagliamonte 2008)) but also includes other categories such as adverbs, nouns, and verbs. For more details on this broader scope, see Roels and Enghels 2020. |

| 9 | In some languages, vocatives are morphologically marked as a case through affixation or declension, as for instance in Latin (Janson 2013). However, its case status has been debated because of its particularities which differentiate the vocative from the other canonical cases: as extra-predicative constituents, vocatives are not governed by a verb or a preposition, and from a morphological angle, they tend to lack case markings in most modern languages, including Spanish (Daniel and Spencer 2009; Moyna 2017). This explains why the phenomenon is most properly defined as a pragmatic-functional category and no longer as a case. |

| 10 | The sample selected for this comparative study only includes the speech of adolescents ranging from 13 to 19 years old. |

| 11 | As the number of words of the selected conversations was not equal for COLAm and CORMA with, respectively, 46,744 and 27,949 words, the frequency was proportionally calculated per 10,000 in each subcorpus. |

| 12 | More specifically, in COLAm, we selected four multiparty (32,107 words) and six one-to-one conversations (14,637 words), while in CORMA, six multiparty conversations (16,353 words) were chosen, as opposed to three one-to-one interactions (11,596 words). |

| 13 | The identification of the vocative expressions is guided by a number of well-established formal operational criteria: (1) the vocative’s extra-propositional and non-argument (thus optional) status; (2) its prosodic autonomy, that is, set-off from the rest of the clause by pauses; and (3) their optional combination with other vocatives or pragmatic markers. |

| 14 | In addition to these general linguistic variables, we also took into account relevant sociolinguistic variables such as (1) speaker’s gender (male, female), (2) addressee’s gender (male, female) in case of the intersubjective vocatives, or (3) neighborhood, as further indication of the social class they belong to (Meyerhoff 2006). Note, however, that a detailed account of the impact of these extralinguistic variables exceeds the boundaries of this paper and is kept for a follow-up study. |

| 15 | A previous study conducted in the entire CORMA corpus (thus, data of all generations) showed a quite different picture, with suffixation as the most frequent strategy (n = 245; 55%) followed by lexical items (n = 131; 29%), and prefixation (n = 70; 16%) (Roels and Enghels 2020). |

| 16 | The types are considered as morphological or lexical items that can fulfill the linguistic function of intensification. However, one type might include morphological (e.g., -azo, -aza) or syntactic (tope pesado/el tope de raro) variation. |

| 17 | We consider the one-offs as signs of creative language use within the corpus, which does not necessarily mean that those one-offs/forms could not have existed in an earlier language stage outside of our corpora. We are well aware of the fact that a comparative corpus study based on two samples has its limits. Needless to say, the fact that a vocative or intensifier does not occur in a corpus does not necessarily mean that it is non-existent in language. |

| 18 | In Appendix A, the two tables present both the literal and the idiomatic meaning of, respectively, the intensifiers and vocatives under scrutiny. |

| 19 | Bearing in mind the small sample, it is still noteworthy that the five observed one-offs were all produced by female teenagers. |

| 20 | In the minimizing construction, the negation denotes the absence of a minimal quantity and hence the presence of no quantity at all (Horn 1989). |

| 21 | Due to overlaps and interruptions, the young girl cannot complete her sentence. However, the context guides the analysis toward the interpretation of the modification of a noun: MS2F3 Obviamente iba a faltar el puto viernes porque me tenía que ir hasta tomar por culo para el sábado tener el puñetero (()) hm- de la com- compe- MS2M7 A un amigo mío […]. The fact that an analogic intensifying mechanism (el puto viernes ‘fucking Friday’) precedes in the left context strengthens this analysis. |

| 22 | The canonical synthetic superlative derives from the Latin form -issimus. In medieval Spanish, the form disappeared but was reincorporated in classical Spanish (Serradilla Castaño 2018). |

| 23 | Example extracted from the Corpus Oral de Lenguaje Adolescente de Madrid (COLAm) (cf. supra Section 3). Parallel to CORMA, the codified names in COLAm also display different social variables. The initial letters reflect the social class of the speaker (e.g., MALCC in this particular case indicates a lower-class teenager of a particular school that received this code), followed by the number of the recorded conversation (e.g., 2). The next letter informs about the gender (e.g., G = male and J = female), and finally, the last number denotes, for instance in this case, the second male speaker of the MALCC school involved in this specific conversation. |

| 24 | The spatial meaning of ‘being beyond or over a given point in space’ was metaphorically reinterpreted as ‘being higher in gradation than a given point’ (Napoli and Ravetto 2017). |

| 25 | In COLAm, no less than 93.4% (n = 127) of the total number of proper names are uttered in multiparty conversations, while in CORMA, this tendency levels up to 97.4% (n = 37). This clearly confirms the functional specialization of proper names of identifying and selecting unique addressees, thanks to its semantic specificity. |

| 26 | The capital letters in the figures represent the lemmas of the different vocative types included in the paradigm. These include distinct morphological variants. For instance, TÍO is the lemma that refers to all generic and numeric variants (tío(s), tía(s)). Moreover, since all proper names share the same semantic-pragmatic characteristics, including their semantic specificity and unique deictic potential to individualize addressees, they are treated as one type. |

| 27 | Although coño cannot be considered a prototypical term of address given its non-human referential meaning (‘pussy’), coño as well as many other more or less grammaticalized forms display a multifunctional behavior, which makes the interpretation of its deictic anchoring very tenuous at times. Still, from a methodological viewpoint, it is pertinent to include also more grammaticalized vocative markers such as coño or hombre (‘man’, also used toward women or a group of interlocutors), also because of their interactive functions, similar to more prototypical vocatives. |

| 28 | Nevertheless, it should be highlighted that the feminine singular form tía is still the default variant to be used toward girls, and all feminine singular tokens are, without exception, used toward a girl, in both COLAm (n = 106; 52.2% of all tío tokens) and CORMA (n = 328; 75.1% of all tío tokens). |

| 29 | Spanish is a pro-drop language, which implies that the use of the subject pronoun is optional (Bernal 2007). According to the criteria applied for the selection of vocatives in this study, the tú-vocatives fulfill the following characteristics: they (1) are extra-propositional and non-argumental, (2) display prosodic autonomy, and (3) may be combined with other vocatives or pragmatic particles, and even verbs that are not in the second-person singular. |

References

- Aarts, Bas, Joanne Close, Geoffrey N. Leech, and Sean Wallis, eds. 2013. The Verb Phrase in English. Investigating Recent Language Change with Corpora. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aijmer, Karin. 2018. That’s well bad: Some new intensifiers in spoken in British English. In Corpus Approaches to Contemporary British English. Edited by Vaclav Brezina, Robbie Love and Karin Aijmer. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 60–95. [Google Scholar]

- Alba de Diego, Vidal, and Jesús Sánchez Lobato. 1980. Tratamiento y juventud en la lengua hablada. Aspectos sociolingüísticos. Boletín de la Real Academia Española 60: 95–130. [Google Scholar]

- Alba-Juez, Laura. 2009. ‘Little words’ in small talk: Some considerations on the use of the pragmatic markers man in English and macho/tío in Peninsular Spanish. In Little Words. Their History, Phonology, Syntax, Semantics, Pragmatics and Acquisition. Edited by Ronald P. Leow, Hector Cámpos and Donna Lardiere. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 171–81. [Google Scholar]

- Albelda Marco, Marta. 2007. La Intensificación como Categoría Pragmática: Revisión y Propuesta: Una Aplicación al Español Coloquial. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Algaba Pérez, Blanca. 2020. A propósito de la Movida madrileña: Un acercamiento a la cultura juvenil desde la Historia. Revista de Historia Contemporánea 21: 319–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce Castillo, Ángela. 1999. Intensificadores en español coloquial. Anuario de Estudios Filológicos 22: 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiadou, Angeliki. 2007. On the subjectivity of intensifiers. Language Sciences 29: 554–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baayen, Rolf Harald. 2009. Corpus linguistics in morphology: Morphological productivity. In Corpus Linguistics. An International Handbook. Edited by Anke Lüdeling and Merja Kytö M. Berlin: Mouton, pp. 900–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Laurie, and Winifred Bauer. 2002. Adjective boosters in the English of young New Zealanders. Journal of English Linguistics 30: 244–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarten, Nicole. 2021. Love as a term of address in British English: Micro-diachronic variation. Contrastive Pragmatics 1: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, Nuria. 2007. Funciones pragmalingüísticas del pronombre personal sujeto tú en el discurso conflictivo del español coloquial. Revista Internacional De Lingüística Iberoamericana 5: 183–99. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Suárez, Zeltia. 2010. On the Origin and Grammaticalisation of the Intensifier Deadly in English. Paper presented at Langwidge Sandwidge, Manchester, UK, October 12. [Google Scholar]

- Blas Arroyo, José Luis. 2005. Sociolingüística del Español: Desarrollos y Perspectivas en el Estudio de la Lengua Española en Contexto Social. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Bolinger, Dwight. 1972. Degree Words. The Hague and Paris: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Brandimonte, Giovanni. 2011. Breve estudio contrastivo sobre los vocativos en el español y el italiano actual. In Del Texto a la Lengua: La Aplicación de los Textos a la Enseñanza-Aprendizaje del Español L2-LE. Edited by Javier de Santiago-Guervós, Hanne Bongaerts, Jorge Juan Sánchez Iglesias and Marta Seseña Gómez. Salamanca: Asociación para la Enseñanza del Español como Lengua Extranjera, pp. 249–62. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Friederike. 1988. Terms of Address. Berlin, New York and München: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Briz Gómez, Antonio. 1998. El español Coloquial en la Conversación: Esbozo de Pragmagramática. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2003. Mechanisms of change in grammaticization: The role of frequency. In The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Edited by Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 602–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2010. Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Richard. 2011. Age, aging and sociolinguistics. In The Handbook of Hispanic Sociolinguistics. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos. Oxford: Willey-Blackwell, pp. 207–29. [Google Scholar]

- Catalá Torres, Natalia. 2002. Consideraciones acerca de la pobreza expresiva de los jóvenes. In El Lenguaje de los Jóvenes. Edited by Félix Rodríguez González. Barcelona: Ariel, pp. 123–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cianca Aguilar, Elena, and Emilio Gavilanes Franco. 2018. Voces y expresiones del argot juvenil madrileño actual. Círculo De Lingüística Aplicada a La Comunicación 74: 147–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuenca, Maria Josep, and Marta Torres Vilatarsana. 2008. Usos de hombre/Home y mujer/dona como marcadores del discurso en la conversación colloquial. Verba 35: 235–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, María Josep. 2004. El receptor en el text: El vocatiu. Estudis Romànics 26: 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, Michael, and Andrew Spencer. 2009. The vocative: An outlier case. In The Oxford Handbook of Case. Edited by Andrej Malchukov and Andrew Spencer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 626–34. [Google Scholar]

- De Latte, Fien. 2021. ’Hola guapa, ¿cómo estás?’: Usos vocativos del adjetivo de belleza guapo en el español peninsular contemporáneo. Oralia 24: 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dimock, Michael. 2019. Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Research Center 17: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, Evelyn. 2005. Adolescência: Definições, conceitos e critérios. Adolesc Saude 2: 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Enghels, Renata, Fien De Latte, and Linde Roels. 2020. El Corpus Oral de Madrid (CORMA): Materiales Para El Estudio (Socio) Lingüístico Del Español Coloquial Actual. Zeitschrift fur Katalanistik 33: 45–76. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanella de Weinberg, María Beatriz. 1999. Sistemas pronominales de tratamiento usados en el mundo hispánico. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, vol. 1, pp. 1399–426. [Google Scholar]

- García Dini, Encarnación. 1998. Algo más sobre el vocativo. In Lo Spagnolo d’oggi: Forme Della Comunicazione (Atti del XVII Convegno AISPI). Roma: Bulzoni, vol. 2, pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- García Palacios, Joaquín, Goedele De Sterck, Daniel Linder, Nava Maroto García, Miguel Sánchez Ibáñez, and Jesús Torres del Rey, eds. 2016. La Neología en las Lenguas Románicas. Recursos, Estrategias y Nuevas Orientaciones. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- García Platero, Juan Manuel. 1997. Sufijación apreciativa y prefijación intensiva en español actual. Lingüística Española Actual 19: 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Grandi, Nicola. 2017. Intensification processes in Italian. In Exploring Intensification: Synchronic, Diachronic & Cross-Linguistic Perspectives. Edited by Maria Napoli and Miriam Ravetto. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gutzmann, Daniel. 2019. The Grammar of Expressivity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haverkate, Henk. 1994. La cortesía Verbal. Estudio Pragmalingüístico. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, Berndt. 2013. On discourse markers: Grammaticalization, pragmaticalization, or something else? Linguistics 51: 1202–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilpert, Martin. 2013. Constructional Change in English: Developments in Allomorphy, word Formation, and Syntax. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hilte, Lisa, Reinhild Vandekerckhove, and Walter Daelemans. 2018. Expressive markers in online teenage talk. Nederlandse taalkunde 23: 293–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelmann, Nikolaus. 2004. Lexicalization and grammaticalization: Opposite or orthogonal? In What Makes Grammaticalization: A Look from Its Fringes and Its Components. Edited by Walter Bisang, Nikolaus Himmelmann and Björn Wiemer. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul, and Elizabeth Closs Traugott, eds. 1993. Grammaticalization. Cambridge: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, Laurence. 1989. A Natural History of Negation. Standford: CSLI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Janson, Tore. 2013. Vocative and the grammar of calls. In Vocative! Addressing between System and Performance. Edited by Barbara Sonnenhauser and Patricia N. Aziz Hanna. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 219–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2009. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, Annette Myre, and Eli-Marie Drange. 2012. La lengua juvenil de las metrópolis Madrid y Santiago de Chile. Arena Romanistica 9: 74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, Annette Myre, and Juan Antonio Martínez. 2009. ‘Tronco/a’ usado como marcador discursivo en el lenguaje juvenil de Madrid. In Actas del II Congreso de Hispanistas y Lusitanistas Nórdicos. Edited by Lars Fant, Johan Falk and María Bernal. Stockholm: Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, Annette Myre. 2007. COLA: Un corpus oral de lenguaje adolescente. Oralia 3: 225–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, Annette Myre. 2008. Tío y tía como marcadores en el lenguaje juvenil de Madrid. In Actas del XXXVII Simposio Internacional de la Sociedad Española de Lingüística (SEL). Edited by Inés Olza Moreno, Manuel Casado Valverde and Ramón González Ruiz. Pamplona: Universidad de Navarra, pp. 387–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, Annette Myre. 2013. Spanish teenage language and the COLAm corpus. Bergen Language and Linguistics Studies 3: 151–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kleinknecht, Friederike, and Miguel Souza. 2017. Vocatives as a source category for pragmatic marker. From deixis to discourse marking via affectivity. In Pragmatic Markers, Discourse Markers and Modal Particles. New Perspectives. Edited by Chiara Fedriani and Andrea Sansó. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 257–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinknecht, Friederike. 2013. Mexican güey—From vocative to discourse marker: A case of grammaticalization? In Vocative! ADDRESSING between System and Performance. Edited by Barbara Sonnenhauser and Patricia N. Aziz Hanna. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 235–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kluge, Bettina, and María Irene Moyna. 2019. It’s Not All about You: New Perspectives on Address Research. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- König, Ekkehard. 2017. The comparative basis of intensification. In Exploring Intensification: Synchronic, Diachronic & Cross-Linguistic Perspectives. Edited by Maria Napoli and Miriam Ravetto. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William. 2007. Transmission and Diffusion. Language 83: 334–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landone, Elena. 2009. Los Marcadores del Discurso y la Cortesía Verbal en Español. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Lara Bermejo, Víctor. 2017. El superlativo absoluto en el español peninsular del siglo XX. Rilce. Revista de Filología Hispánica 34: 225–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lázaro Carreter, Fernando. 1979. Una jerga juvenil: ‘el cheli’. ABC 16: 118. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, Geoffrey N. 1999. The distribution and functions of vocatives in American and British English conversation. In Out of corpora: Studies in honour of Stig Johansson. Edited by Hilde Hasselgård and Signe Oksefjell. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 107–18. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, Geoffrey N. 2014. The Pragmatics of Politeness. Oxford Studies in Sociolinguistics. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, Christian. 1985. Grammaticalization: Synchronic variation and diachronic change. Lingua Stile 20: 303–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, Christian. 2002. Thoughts on Grammaticalization. Erfurt: Seminar für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität. [Google Scholar]

- Llopis Cardona, Ana, and Salvador Pons Bordería. 2020. La gramaticalización de macho y tío/a como ciclo semántico-pragmático. Círculo De Lingüística Aplicada a La Comunicación 82: 151–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, Gunter. 2002. Really worthwhile or not really significant? A corpus-based approach to the delexicalization and grammaticalization of intensifiers in Modern English. In New Reflections on Grammaticalization. Edited by Ilse Wischer and Gabriele Diewald. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 143–61. [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay, Ronald. 2006. Pure grammaticalization: The development of a teenage intensifier. Language Variation and Change 18: 267–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhoff, Miriam. 2006. Introducing Sociolinguistics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Molina Martos, Isabel. 2010. Difusión social de una innovación lingüística: La intensificación en el habla de las jóvenes madrileñas. Oralia 13: 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Moyna, María Irene. 2017. Voseo vocatives and interjections in Montevideo Spanish. In Contemporary Advances in Theoretical and Applied Spanish Linguistic Variation. Edited by Colomina Alminana and Project Muse. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, pp. 124–47. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli, Maria, and Miriam Ravetto. 2017. Ways to intensify: Types of intensified meanings in Italian and German. In Exploring Intensification: Synchronic, Diachronic & Cross-Linguistic Perspectives. Edited by Maria Napoli and Miriam Ravetto. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 327–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs, Elinor. 1996. Linguistic resources for socializing humanity. In Rethinking Linguistic Relativity. Edited by John J. Gumperz and Stephen C. Levinson. Cambridge: CUP, pp. 407–38. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios Martínez, Ignacio, and Paloma Núñez Pertejo. 2014. Strategies used by English and Spanish teenagers to intensify language: A contrastive corpus-based study. Spanish in Context 11: 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, Heike. 2010. Methods in discourse variation analysis: Reflections on the way forward. Journal of Sociolinguistics 14: 581–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Potts, Christopher. 2007. The expressive dimension. Theoretical Linguistics 33: 165–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey N. Leech, and Jan Svartvik. 1985. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Rendle-Short, Johanna. 2010. Mate as a term of address in ordinary interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 42: 1201–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez González, Félix, ed. 2002. El Lenguaje de los Jóvenes. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Ponce, María Isabel. 2002. La Prefijación Apreciativa en Español. Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, González Félix, and Anna-Brita Stenström. 2011. Expressive Devices in the Language of English-and Spanish-Speaking Youth. Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses 24: 235–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roels, Linde, and Renata Enghels. 2020. Age-Based Variation and Patterns of Recent Language Change: A Case-Study of Morphological and Lexical Intensifiers in Spanish. Journal of Pragmatics 170: 125–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serradilla Castaño, Ana. 2018. De «asaz fermoso» a «mazo guapo»: La evolución de las fórmulas superlativas en español. In Actas del X Congreso Internacional de Historia de la Lengua Española: Zaragoza, 7–11 de septiembre de 2015. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico, pp. 913–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shoeni, Anna, Katharina Roser, and Martin Röösli. 2015. Memory performance, wireless communication and exposure to radiofrequency electromagnetic fields: A prospective cohort study in adolescent. Environment International 85: 343–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sonnenhauser, Barbara, and Patrizia N. Aziz Hanna, eds. 2013. Vocative!: Addressing between System and Performance. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Stenström, Anna-Brita. 2005. He’s well nice—Es mazo majo: London and Madrid teenage girls’ use of intensifiers. In The Power of Words: Studies in Honour of Moira Linnarud. Edited by Solveig Granath, June Miliander and Elisabeth Wenno. Karlstad: Karlstad University, pp. 207–16. [Google Scholar]

- Stenström, Anna-Brita. 2008. Algunos rasgos característicos del habla de contacto en el lenguaje de adolescentes en Madrid. Oralia 11: 207–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali. 2008. So different and pretty cool! Recycling intensifiers in Toronto, Canada. English Language and Linguistics 12: 361–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, Sali. 2016. Teen Talk: The Language of Adolescents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, Peter. 2020. Sociolinguistic typology and the speed of linguistic change. Journal of Historical Sociolinguistics 6: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urichuk, Matthew, and Verónica Loureiro-Rodríguez. 2019. Brocatives: Self-reported use of vocatives in Manitoba (Canada). In It’s Not All about You—New Perspectives on Address Research. Edited by Bettina Kluge and María Irene Moyna. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 355–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zeldes, Amir. 2012. Productivity in Argument Selection. From Morphology to Syntax. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Zeschel, Arne. 2012. Incipient Productivity: A Construction-Based Approach to Linguistic Creativity. Berlin and New York: Mouton De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, Klaus. 2002. La variedad juvenil y la interacción verbal entre jóvenes. In El Lenguaje de los Jóvenes. Edited by Félix Rodríguez González. Barcelona: Ariel, pp. 137–64. [Google Scholar]

| COLAm | CORMA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Class | High Class | Total | Low Class | High Class | Total | |

| boys | 7 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| girls | 8 | 7 | 15 | 6 | 7 | 13 |

| Total | 15 | 16 | 31 | 13 | 14 | 27 |

| # Absolute | # Normalized | |

|---|---|---|

| COLAm | 191 | 40.9 |

| CORMA | 240 | 85.9 |

| Total | 431 | 57.8 |

| COLAm | CORMA | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | # norm. | % | # | # norm. | % | # | % | |

| prefixes | 21 | 4.5 | 11 | 22 | 7.9 | 9.2 | 43 | 10 |

| suffixes | 39 | 8.3 | 20.4 | 30 | 10.7 | 12.5 | 69 | 16 |

| lexical items | 131 | 28 | 68.6 | 188 | 67.3 | 78.3 | 319 | 74 |

| Total | 191 | 40.8 | 100 | 240 | 85.9 | 100 | 431 | 100 |

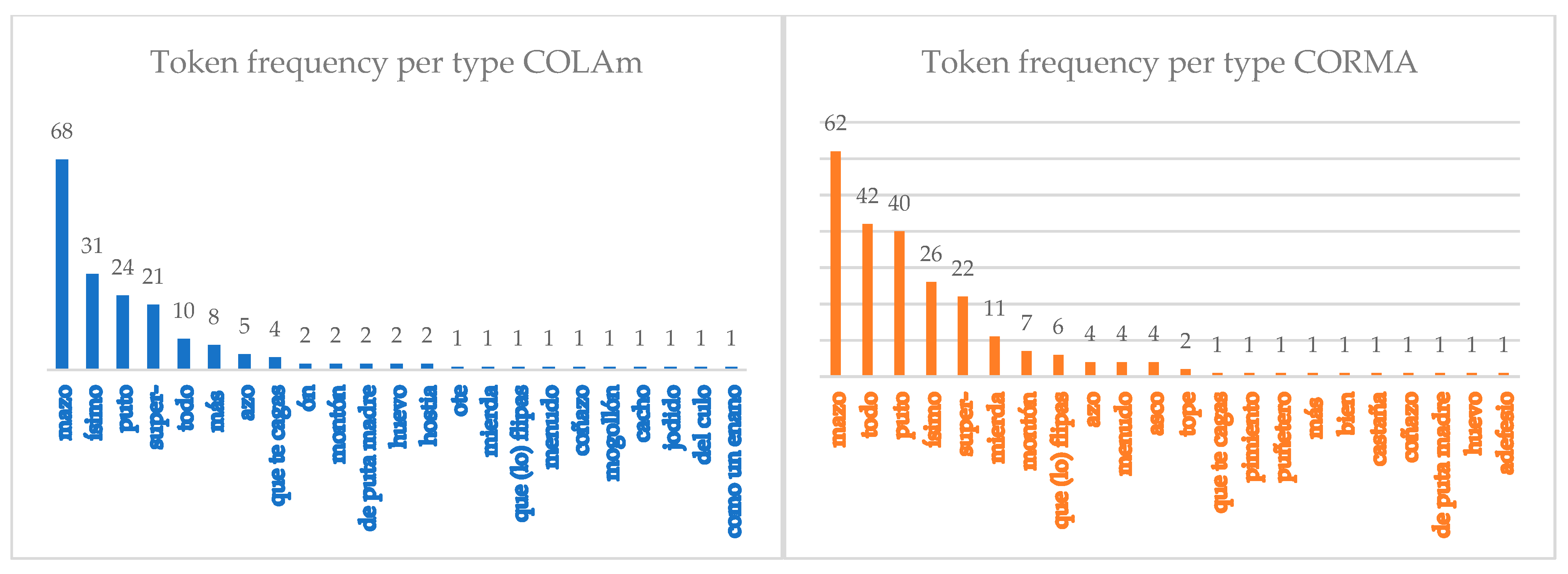

| Types (15) | COLAm | CORMA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | # norm. | % | # | # norm. | % | |

| mazo ‘really, a lot’ | 68 | 14.6 | 35.6 | 62 | 22.2 | 25.8 |

| -ísimo ‘very’ | 31 | 6.6 | 16.2 | 26 | 9.3 | 10.8 |

| puto ‘fucking’ | 24 | 5.1 | 12.6 | 40 | 14.3 | 16.7 |

| super- ‘super’ | 21 | 4.5 | 11 | 22 | 7.9 | 9.2 |

| to(do) ‘very’ | 10 | 2.1 | 5.2 | 42 | 15 | 17.5 |

| más ‘most’ | 8 | 1.7 | 4.2 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| -azo ‘nice, great’ | 5 | 1 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| que te cagas ‘extremely, very well’ | 4 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| montón ‘a heap, a lot’ | 2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 7 | 2.5 | 2.9 |

| de puta madre ‘fucking great’ | 2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| huevo ‘as shit’ | 2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| mierda ‘shitty’ | 1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 11 | 3.9 | 4.6 |

| que (lo) flipas ‘extremely, like crazy’ | 1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 6 | 2.2 | 2.5 |

| menudo ‘what a …’ | 1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 4 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| coñazo ‘a pain in the ass’ | 1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Total | 181 | 38.7 | 94.5 | 229 | 82 | 95.4 |

| # Absolute | # Normalized | |

|---|---|---|

| COLAm | 607 | 129.9 |

| CORMA | 586 | 209.7 |

| Total | 1193 | 159.7 |

| COLAm | CORMA | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | # norm. | % | # | # norm. | % | # | % | |

| proper names | 136 | 29.1 | 22.4 | 38 | 13.6 | 6.5 | 174 | 14.6 |

| nominal ToA | 440 | 94.1 | 72.5 | 510 | 182.5 | 87 | 950 | 79.6 |

| 2nd-pers. pron. | 31 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 38 | 13.6 | 6.5 | 69 | 5.8 |

| Total | 607 | 129.9 | 100 | 586 | 209.7 | 100 | 1193 | 100 |

| Types (11) | COLAm | CORMA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | # norm. | % | # | # norm. | % | |

| TÍO ‘dude’ | 203 | 43.4 | 33.4 | 437 | 156.4 | 74.6 |

| TRONCO ‘dude’ | 100 | 21.4 | 16.5 | 6 | 2.1 | 1 |

| tú ‘you’ | 31 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 38 | 13.6 | 6.5 |

| CHAVAL ‘boy’ | 31 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 3 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| hombre ‘man’ | 29 | 6.2 | 4.8 | 15 | 5.4 | 2.6 |

| coño ‘pussy’ | 18 | 3.9 | 3 | 8 | 2.7 | 1.4 |

| HIJO ‘son’ | 15 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| CHICO ‘kid’ | 3 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 6 | 0.7 | 1 |

| macho ‘dude’ | 2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| HIJO DE PUTA ‘son of a bitch’ | 2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| cabrón ‘bastard’ | 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 7 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| Total | 435 | 93 | 71.7 | 525 | 187.8 | 89.6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roels, L.; De Latte, F.; Enghels, R. Monitoring 21st-Century Real-Time Language Change in Spanish Youth Speech. Languages 2021, 6, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040162

Roels L, De Latte F, Enghels R. Monitoring 21st-Century Real-Time Language Change in Spanish Youth Speech. Languages. 2021; 6(4):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040162

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoels, Linde, Fien De Latte, and Renata Enghels. 2021. "Monitoring 21st-Century Real-Time Language Change in Spanish Youth Speech" Languages 6, no. 4: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040162

APA StyleRoels, L., De Latte, F., & Enghels, R. (2021). Monitoring 21st-Century Real-Time Language Change in Spanish Youth Speech. Languages, 6(4), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040162