The source languages of Light Warlpiri encode reflexivity and reciprocity in different ways—English and Kriol use pronominal forms, and for the most part, have different forms for reflexives versus reciprocals. Warlpiri uses a single clitic in the auxiliary to express both types of events. How do these play out in Light Warlpiri? The structural encoding of reflexives and reciprocals in Light Warlpiri is described first, followed by semantic scope.

5.1. Structural Encoding: Light Warlpiri

Light Warlpiri uses a single form for both reflexive and reciprocal expressions. The form is an affix -selp, derived from English -self. The affix attaches to English- and/or Kriol-derived pronominal subject forms for each person and number, forming the construction PRO-REFL/RECIP. The pronominal forms agree with the clausal subject, which need not be overtly expressed in the clause. The weak pronominal forms for 2nd (yu, yumob) and 3rd person (i, de(m)), are the same as those in non-coreferential clauses. The 1st person form, mai ‘1SG.POSS’ also occurs as a possessive, but the 1st person form au ‘1PL.POSS’ does not usually occur in Light Warlpiri. This suggests that there is a reflexive–reciprocal unit comprised of PRO-REFL/RECIP. The phonetic realisation of the final consonant in -selp is a bilabial plosive [p], represented orthographically here as ‘p’. The vowel quality was not analysed for this study; it appears to be in the range from a low front to mid-front vowel, /æ/ to /ε/.

The PRO-REFL/RECIP complex occurs within a verbal word. Evidence for this is that it occurs between the lexical verb stem (with or without progressive and/or transitive marking) and the verbal iterative affix

-pat ‘ITER

’, derived from Kriol

-bat ‘ITER’. The orthographic representation of

-pat is due to the auditory impression that the initial consonant is a voiceless plosive, supported by inspection of several tokens in Praat (

Boersma 2001). There is a single example in the corpus of a reflexive marker following iterative

-pat, in (23). It is not clear whether it represents a switch to Kriol or is a possible construction in Light Warlpiri. Other Light Warlpiri speakers did not replicate the structure in discussions, so we conclude that this is not a stable structure in Light Warlpiri.

| 23. | de | kliin-im-pat | de-selp | na |

| | 3PL | clean-TR-ITER | 3PL-REFL | DIS |

| | ‘They’re cleaning themselves now.’ |

| | (LAC58_CircleOfDirt) |

Examples of reflexive marking are given in (24) and (25), and of reciprocal marking in (26) and (27).

| 24. | a=m | wash-mai-selp-pat | ngapa-nga |

| | 1SG=NFUT | wash-1SG-REFL-ITER | water-LOC |

| | “I washed and washed myself in the water.” |

| | (Elicit_LA21_2020) |

| 25. | i=m | puk-im-i-selp-pat | every | minute | niidil-kurlu-ng |

| | 3SG=NFUT | poke-TR-3SG-REFL-ITER | every | minute | needle-COM-ERG |

| | “She poked herself over and over with the needle.” |

| | (Elicit_LA21_2020) |

| 26. | a | nyampu-rra-ng | de=m | slap-de-selp-pat |

| | DIS | DEM-PL-ERG | 3PL=NFUT | slap-3PL-RECIP-ITER |

| | “Ah these, they are slapping each other.” |

| | (Recip_LAC58) |

| 27. | a | de=m | jis | gib-de-selp-pat | ebrithing |

| | DIS | 3PL=NFUT | just | give-3PL-RECIP-ITER | everything |

| | “Ah they are just giving each other everything.” |

| | (Recip_LAC58) |

The reflexive–reciprocal affix can also occur following a progressive marker derived from English

-ing ‘PROG’, as in (28).

| 28. | Nyampu-rra-ng | de | slap-ing-de-selp-pat |

| | DEM-PL-ERG | 3PL | slap-PROG-3PL-RECIP-ITER |

| | “These are slapping each other.” |

| | (Recip_LAC58) |

The construction of reflexive–reciprocal

PRO-selp occurring between a lexical verb stem and aspectual

-pat raises a question of the status of

-pat in Light Warlpiri. In Kriol,

-bat functions as an aspectual marker, associated with continuous and iterative actions (

Hudson 1985, p. 40;

Schultze-Berndt et al. 2013, p. 7), and of plural participants (

Hudson 1985, pp. 39–40). In the Light Warlpiri data, the affix

-pat only occurs on verbs, not in any position that could be construed as nominal, and does not have other nominal properties, for instance, hosting nominal affixes. The affix

-pat is present in events where an action is performed repeatedly and sequentially, often by more than one actor, and for most speakers, involves more than two participants in the event. While not all repeated, sequential actions with plural participants are encoded with aspectual

-pat, only two instances of

-pat out of 19 occurrences encode a non-repetitive, non-sequential action with fewer than three participants, and the event in both instances is one of continuous ‘leaning’, where two people lean against each other, back-to-back (see the image in

Appendix A). This is in line with a link between iterativity and continuity. In conclusion,

-pat is a verbal aspectual affix indicating iterative, continuous actions and/or plural participants, glossed as

-pat ‘ITERATIVE’.

In terms of prosody, impressionistically the main stress in the verbal word occurs on the first and last syllables, i.e., on the first syllable of the lexical stem and on iterative -pat, if present. When iterative -pat is not present the main stress is on the first syllable. Iterative -pat appears to be realised with relatively long vowel duration and relatively greater amplitude. This supports the analysis of a multimorphemic verbal word, perhaps with an emphasis on the peripheral syllables as word boundaries. However, an acoustic analysis of prosody remains for future work.

Although the verbal construction with

-pat present provides evidence of the verbal nature of reciprocal and reflexive marking, the constructions with occurrences of

-pat account for only 12% of the instances of the morphological reflexive–reciprocal. Examples of reflexive marking for each person and number where

-pat is not present are given in (29–34), and of reciprocal marking in (35–37).

| 29. | A=m | puk-mai-selp | niidil-kurlu-ng |

| | 1SG=NFUT | poke-1SG-REFL | needle-COM-ERG |

| | “I poked myself with a needle.” |

| | (Elicit_LA21_2020) |

| 30. | wi | meik-au-selp | fal-dan | jalpi |

| | 1PL | make-1PL-REFL | fall-down | self |

| | “We make ourselves fall down, on our own.” |

| | (Elicit_LAC10_2020) |

Interestingly, example (30) shows the use of a different form also derived from English ‘self’,

jalpi ‘self’, but the meaning is not reflexive. The meaning of

jalpi ‘self’ is that of ‘by one’s self’ or ‘on one’s own/alone’. All of the instances of

jalpi in the data have this meaning, and are distinct in pronunciation and surrounding morphosyntactic structure from the reflexive–reciprocal affix

-selp.

| 31. | ngaka-jala | yu | garra | luk-yu-selp | nganayi | vidia-ngka |

| | later-EMPH | 2SG | FUT | see-2SG-REFL | something | video-LOC |

| | “You’ll see yourself on the video later.” |

| | (CO2_8a) |

| 32. | go | swim | meik-yumob-selp | fresh |

| | go | swim | make-2PL-REFL | fresh |

| | “Go and swim and refresh yourselves.” |

| | (Elicit_LAC10_2020) |

| 33. | i=m | hurt-i-selp |

| | 3SG=NFUT | hurt-3SG-REFL |

| | “He hurt himself.” |

| | (2008ERGstory_LA62) |

In transitive sentences, the reflexive pronominal expression attaches to the verb stem, and an allomorph of the transitive marker,

-im ‘TRANS’ is not present. There is a single occurrence of a reflexive form occurring independently of a pronoun, as part of a prepositional phrase headed by the English-derived preposition,

with, as in (34), however, this may be an instance of a slip-of-the-tongue type error.

| 34. | De=m | get | api | with | selp | na |

| | 3PL=NFUT | INCHO | happy | with | reflex | DIS |

| | “They are happy with themselves.” |

| | (2008ERGstoryLA62) |

Examples of reciprocal marking for each person and number are given in (35)–(37).

| 35. | wi | ag-ing-au-selp |

| | 1PL | hug-PROG-1PL-RECIP |

| | “We are hugging each other.” |

| | (Elicit_LAC10_2020) |

| 36. | yumob | garra | panj-yumob-selp | ngana | mayi |

| | 2PL | FUT | punch-2PL-RECIP | who | Q |

| | “You will all punch each other, I don’t know who.” |

| | (C03_14) |

Example (36) shows that, as with reflexives, the reciprocal expression attaches to the verb stem, and the transitive marker allomorph,

-im ‘TR’ is not present.

| 37. | a | nyampu-rra-ng | dei | gib-ing-de-selp |

| | DIS | DEM-PL-ERG | 3PL.S | give-PROG-3PL-RECIP |

| | kardiya-wati-ng | | ebrithing | |

| | non.Indigenous-PL-ERG | everything |

| | “Ah, these non-Indigenous people are giving each other everything.” |

| | (Recip_LAC58) |

The reflexive–reciprocal affix can occur following a progressive marker derived from English -ing ‘PROG’, as in (35) and (37). If the progressive verb is transitive, transitive -it attaches to -ing, and the reflexive–reciprocal follows, as in (38). There are no instances of -ing following the reciprocal in the data. The pronoun dei ‘3PL.S’ in (37) is a pronominal allomorph that occurs when there is no overt TMA marking in the auxiliary, and the verb is marked with a progressive affix. Reflexive–reciprocal marking does not change the valency of the verb, as shown in (37), where the transitive subject argument nyampu-rra ‘DEM-PL’ is marked with an ergative case-marker.

There are three instances in the data of English each other, from two speakers, suggesting that this is possible, but not the conventional expression of reciprocals. It is not clear if this should be categorised as a switch to English or as Light Warlpiri. For this reason, this encoding is not discussed further here.

Reflexive and Reciprocal Encoding for Dative Arguments

In a clause with two nonsubject arguments, the reflexive–reciprocal element can follow a dative affix, as in (38).

| 38. | De | pass-ing-it-bo-de-selp-pat |

| | 3PL | pass-PROG-TR-DAT-3LP-RECIP-ITER |

| | ‘They’re passing it to each other.’ |

| | (Recip_LAC41) |

Dative

bo ‘DAT’ is derived from English ‘for’ in word-shape, and combines with Warlpiri dative semantics to function as a dative marker, that can be glossed in English as ‘to, for’ (cf.

O’Shannessy 2016). Five of the six speakers produce the dative construction, and they account for 15% of expressions of reciprocal events in the data. Only one speaker produced a verb like that in example (38), where both dative and iterative affixes are present. Dative

bo ‘DAT’ has previously been documented as being external to the verb (

O’Shannessy 2016, p. 89), but new data in this paper, in (38), show that it is internal to the verb, as it occurs between the verbal transitive marker and reflexive–reciprocal affix, which in turn occurs before the iterative affix. A dative element occurring within a verb complex suggests the influence of Warlpiri, where dative cases can be marked both in the auxiliary and on NPs. For instance, in a Warlpiri clause with the verb,

wangka- ‘talk, speak’, the dative case is registered in the auxiliary and on the overt nonsubject nominal, as in example (39).

| 39. | wati | ka=rla | wangka-mi | nyanungu-parnta-ku |

| | man | PRES=DAT | speak-NPST | 3SG-partner-DAT |

| | “The man talks to his partner.” |

| | (2010ERGstory_YWA04) |

Events for which speakers use a dative affix in Light Warlpiri are encoded either by verbs whose translational equivalents in Warlpiri select a dative nonsubject argument, or by dative-marked nominals.

| 40. | wanti-ja=ø=rla | leda-ju | jarntu-ku |

| | fall-PAST=3SG=DAT | ladder-TOP | dog-DAT |

| | “The ladder fell on the dog.” |

| | (O’Shannessy 2016, p. 89) |

Example (40), in which the dative case appears in an adjunct construction in Warlpiri, illustrates that in the phonological realisation the dative appears to attach directly to the verb. In Warlpiri, this occurs when the auxiliary pronominal affix has no phonological realisation, because the verb form is past tense and the grammatical subject is third person singular. We speculate that this may have influenced the Light Warlpiri structure of a dative element occurring in the verb.

In Light Warlpiri,

tok ‘talk, speak’ takes a dative nonsubject argument, under influence from Warlpiri (cf.

O’Shannessy 2016). Other Light Warlpiri verbs that select a dative nonsubject argument include ditransitive verbs, e.g., ‘give’, and ‘pass’, as in ‘pass x to y’, and an inchoative verb

get ‘INCHO’ modeled on Warlpiri.

An example of dative marking both within the verb and on a nominal in Light Warlpiri is given in example (41). In (41) the English-derived verb

get ‘INCHOATIVE’ shows Warlpiri-derived inchoative meaning, under influence from a Warlpiri structure involving a pre-verbal element and an inchoative inflecting verb,

-jarrimi ‘INCHO’.

| 41. | De | get-bo-de | api | olot-ik-juk |

| | 3PL | INCHO-DAT-3PL | happy | whole.lot-DAT-yet |

| | “They become happy with themselves/each other.” (LIT: ‘they become-for-them happy whole.lot-for-yet’) |

| | (Recip_LAC04) |

A reflexive–reciprocal marker is not obligatory when expressing a reflexive–reciprocal event. The object pronoun

dem ‘3PL.O’, also in a contracted form,

de ‘3PL.O’, attached to the dative marker but without a morphological reciprocal affix, is used by three speakers to refer to reciprocal events, as in (42). This type of construction accounts for 3.7% of encodings of reciprocal events.

| 42. | De=m | gib-bo-de | rdaka | jirrama-ng |

| | 3PL=NFUT | give-DAT-3PL | hand | two-ERG |

| | “They give each other a handshake.” (LIT: ‘they give-for-them hand two-ERG’) |

| | (Recip_LAC04) |

The encodings of reflexivity and reciprocity in Light Warlpiri are summarised in

Table 5.

5.3. Semantic Encoding of Reciprocity in Light Warlpiri and Warlpiri

The reciprocals elicited production task was undertaken by six Light Warlpiri speakers and one Warlpiri speaker (and the Warlpiri speaker is not a speaker of Light Warlpiri). There is both variation and agreement across speakers in terms of the semantics of events that are encoded using a reciprocal construction. Some reciprocal events elicited responses from some speakers that did not include the reciprocal affix, -selp, so the construction with -selp is here called a morphological reciprocal construction. Statistical analyses are not run on the data because of the small number of tokens, yet the numbers are sufficient to identify tendencies in how speakers encode the events.

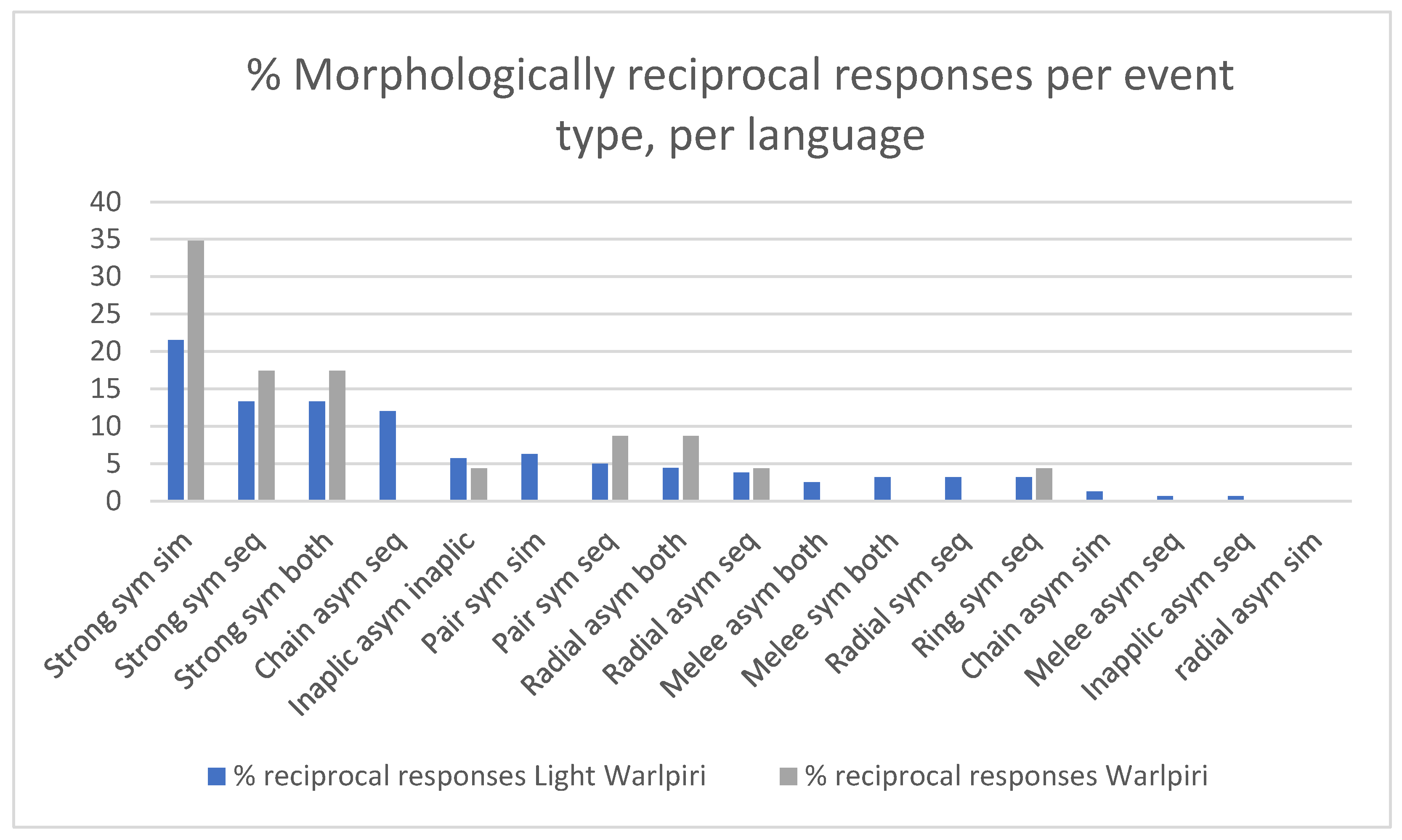

The events that elicited the most tokens of morphologically reciprocal constructions are those categorised as strong, which includes symmetrical action. Strong events account for 48% (

n = 76) of all reciprocal responses in Light Warlpiri and for 70% (

n = 16) of them in Warlpiri. Strong simultaneous events elicited more morphological reciprocal expressions than strong sequential events did. For all other types of events, the responses are spread fairly evenly in Light Warlpiri, less so in Warlpiri. In Light Warlpiri chain events received the next most responses with a morphological reciprocal (13%,

n = 21), while in Warlpiri pair and radial events did (9% each,

n = 2 (pair),

n = 3 (radial)). The percentages of event types that received morphological reciprocal responses in Light Warlpiri and Warlpiri are summarised in

Figure 1.

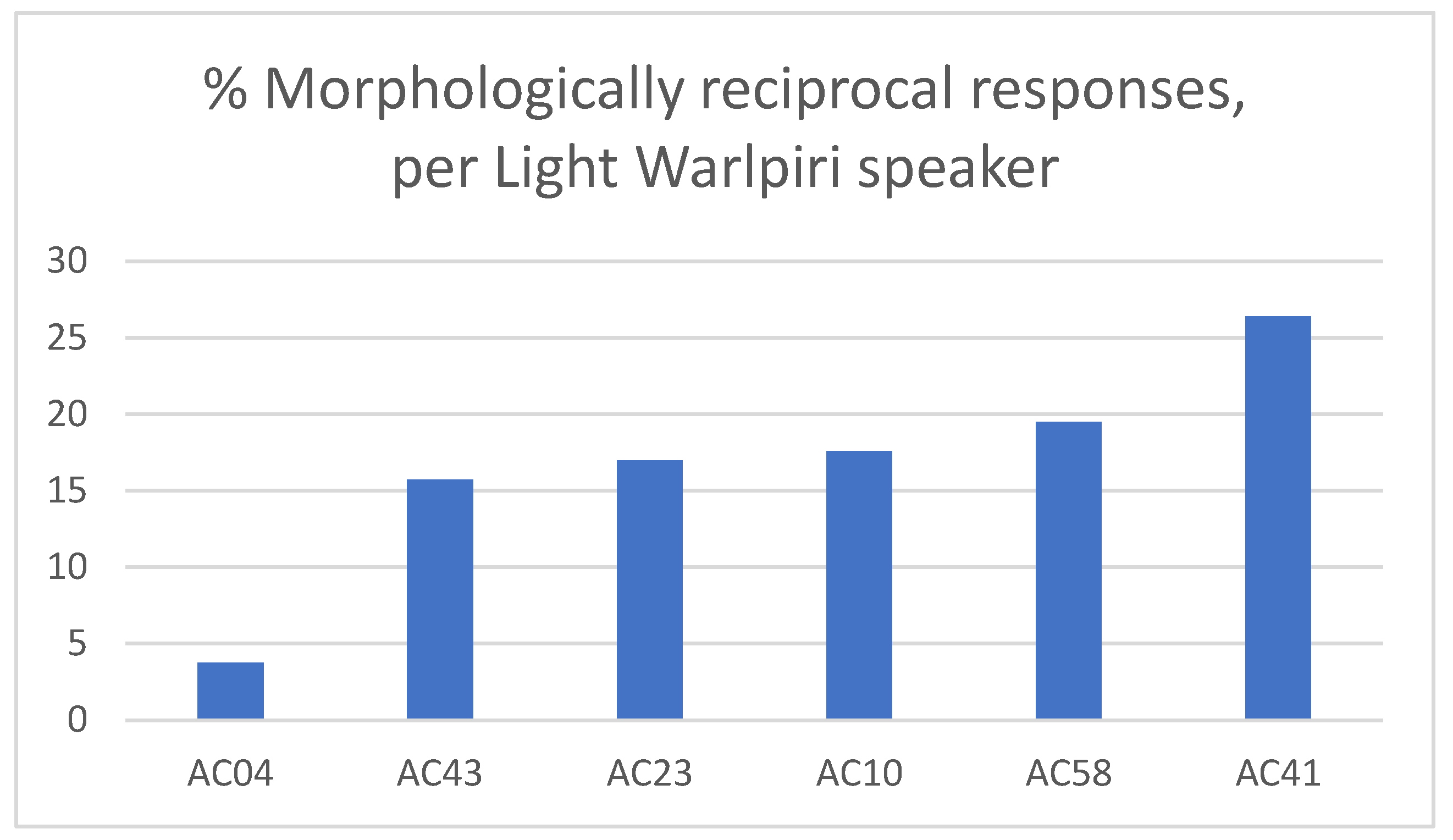

The responses in Light Warlpiri show considerable individual variation, with five speakers along a cline of how often an event receives a reciprocal expression, and one speaker using morphological reciprocal expressions much less often than the others (see

Figure 2). This speaker also produced more dative expressions without a morphological reciprocal marker than other speakers did, e.g.,

bo de(m) ‘DAT 3PL’, as in example (42) above. The speaker who diverges from the others produced only 4% of all morphologically reciprocal responses in Light Warlpiri, and the other five speakers each produced between 16–26% of responses. The number of morphologically reciprocal responses for these five speakers ranges from 25 to 42 responses each. For comparison, the Warlpiri speaker produced 26 responses using the morphological reciprocal marker. All six Light Warlpiri speakers have lived in the Lajamanu community all of their lives, but the speaker with divergent patterning has spent more time visiting the major centre, Darwin, than the other speakers have, and therefore has had more exposure to ways of talking other than Warlpiri and Light Warlpiri. It is hypothesised that this may be the reason for the difference, but there may be other sociolinguistically motivated reasons unknown to the authors.

The clearest agreement across speakers is seen when an event is not encoded with a morphological reciprocal. Fourteen events were not encoded with a morphological reciprocal by any speaker, either in Light Warlpiri or Warlpiri. Of these, twelve involve asymmetrical actions, and ten do not involve simultaneous actions. Seven are events in which one person acts on another but the action is not reciprocated.