Abstract

This paper focuses on the way in which small and medium-sized businesses in Flanders adapted communication with their customers during the economic lockdown in March–May 2020. It documents, more specifically, how shops tried to maintain, re-establish, or even re-invent communication with their customers during this two-month period. Based on pictures of shop windows in a Flemish city, we analyze the (semi-)commercial messages that appeared in this setting during this period. This analysis adopts an interdisciplinary perspective, in which a cognitive linguistic approach is integrated with analyses and practical advices by marketing agencies. Despite their orientation towards distinct, theoretical and practical goals, both approaches share an analytical interest in mapping participants and their mutual relationship as part of a communicative interaction. In the period of economic lockdown, marketers urged shop owners to ‘humanize’ their business strategy by downplaying content-related issues in favor of maximal social outreach towards customers. Considering this advice, it was hypothesized that under these circumstances participants in commercial transactions would be construed much more prominently, presenting themselves and each other as unprecedented empathetic business personas. Much of our data comply with this expectation, thus providing empirical evidence of a subjectified communicative ground, in which both buyer and seller personas figure with augmented prominence as parts of the object of conceptualization. Messages include, among other things, expressions of empathy, solidarity, combativity, but also creativity and humor thus incorporating a new type of humanized business communication. With respect to the analysis of marketing strategies, the collected data at the same time instantiate and legitimize marketers’ communication advice about humanizing one’s business exchange.

1. Introduction

Early March 2020, Belgium, just like major parts of Europe and the world, faced a rapid increase of infections with the COVID-19 coronavirus among its population. To prevent an uncontrolled outbreak of the virus, the Belgian government ordered an almost general lockdown of its society, allowing only essential entities like food and retail businesses, (air)ports, medical services etc. to remain open. All so-called ‘non-essential’ shops were closed between 18th March and 18th May 2020. This study focuses on the way in which small and medium-sized non-essential businesses in Flanders tried to make sense of the fact that they were cut off from their customers for two months. More specifically, we analyze the way in which businesses attempted to maintain, re-establish, or even re-invent communication with their customers during this two-month period. In line with the methodological steps laid out by modern linguistic landscape research (Gorter 2018), our approach is based on multiple pictures of shop windows in the Flemish city of Leuven, in which we analyzed the (semi-)commercial messages that appeared in this specific setting during this period. In our aim to uncover the socio-cognitive meaning of these creative messages along with the underlying construal mechanisms, our analytical focus adopts an interdisciplinary perspective integrating both a cognitive linguistic approach and practical advice of marketing agencies. Despite their orientation towards distinct, both theoretical and practical goals, these two analytical models share a common interest in carefully mapping participants and their interactional relationship as part of the so-called communicative ground.

Already during the economic lockdown, marketers gave out warning signals about an unmistakable seismic shift shaking up consumer behavior because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, companies were urged to fundamentally revise their so-called buyer personas, which are commonly defined as highly elaborated, semi-fictional representations of a business’ ideal customer(s). At the core of their advice, marketers argued in terms of humanizing one’s business strategy by downplaying content-related issues in favor of maximizing social outreach hence expressing genuine involvement in empathetic, supportive, engaged, trustworthy and credible behavior.

Considering this advice, it might be expected that compared to the pre-coronavirus period, both buyer and seller personas—mutually assumed key participants in the business process and as such members of the communicative ground in this type of interaction—be construed much more prominently, thus revealing themselves as empathetic business personas. Interestingly, most of the examples in our data comply with this expectation. Several aspects of both buyer and seller personas do indeed appear as objects of their conceptual content. For instance, messages include, among other things, expressions of empathy (we care for you), solidarity (together we shall overcome this), combativity (let’s beat corona), but also creativity and humor. Messages like these draw our attention because under regular, non-COVID conditions we are not used to this type of content in a commercial setting. Elements of the communicative ground like the business participants (buyer and seller) as well as material aspects of the message itself (marked, for instance, by vintage technology and materials used) are being highlighted as parts of the conceptualized content, thus embodying the humanized aspect of this type of interaction (Androutsopoulos 2020, pp. 295–98; Ramjaun 2020; Dancygier et al. forthcoming). This interdisciplinary study provides empirical support for the linguistic analysis of this type of communication in terms of (inter)subjective construal, which categorizes the operation of pulling elements of the ground towards the center of an expression’s conceptualized meaning. On the content level, our data at the same time seem to instantiate and legitimize the marketers’ COVID-related strategic advice of humanizing business communication.

In line with these observations, this paper pursues both a content-related and a methodological objective. On the level of marketing-driven business communication, first, our case study aims to demonstrate that under drastically changed societal circumstances, as is the case with the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses’ marketing and communication processes cannot be continued as if it were ‘business as usual’. On the level of local, off-line shops and businesses, our small-scale study provides empirical evidence demonstrating a fundamental shift in business communication at an early stage of the first lockdown in Spring 2020. It shows, more precisely, how in this specific period of time product-oriented brand communication, considered the mainstream type of business communication in pre-COVID days, is relieved by a different type of communication, which plays on general human values like empathy and solidarity, which in pre-COVID times instantiated an atypical model of business communication.

Our second objective relates to the interdisciplinary nature of this study as it involves the integration of a cognitive linguistic methodological approach into a marketing-related analysis. We will show, more specifically, that the operationalization of two ground-related mechanisms of cognitive construal, objectification and subjectification, serves the goal of obtaining a more fine-grained analysis of the creative variation in this type of communication. At the same time, a close-reading analysis of these (semi-)commercial messages in terms of construal operations makes complex theoretical constructs like common ground assumptions, intersubjectivity, theory of mind etc. very tangible in the ways they are being applied in a highly elaborate and realistic usage event.

The paper is structured in six main sections. Section two describes the complementary framework of cognitive linguistics (Section 2.1) and marketing analysis (Section 2.2). Section three elaborates on the empirical set-up of this study along with the resulting corpus of pictures. In section four, we describe eighteen cases illustrating this humanized business communication and which in technical terms of underlying linguistic construal operations can be identified as instances of subjectification or—in case the increased focus on the communicative ground is reflected by linguistic sanctioning—objectification. In section five, we reassemble the linguistic and marketing perspectives for a final reflection over the empirical data followed by, in section six, a description of what may be some of the wider implications of this interdisciplinary study. We conclude this paper in Section 7 by wrapping up its major findings.

2. Mapping Participants in Business Interaction

Despite their orientation towards distinct theoretical and practical goals, both cognitive linguistics and strategic marketing analysis share a common interest in mapping participants in their mutually dynamic relationship as part of the communicative interaction under scrutiny. On the background of what both theoretical models characterize as regular and unmarked shop window-communications, it will be interesting to observe along which dimensions of construal the (potential) participants of this new and distant type of commercial interaction—buyers and sellers but other people as well—will be represented.

2.1. Construing the Ground in Cognitive Linguistics

2.1.1. Meaning is Conceptualization

Cognitive linguistics qualifies as a usage-based account of meaning, according to which meaning is not a system-inherent value sticking to a linguistic form. Instead, meaning is said to emerge from the rich conceptual structure of our encyclopedic knowledge as well as from our embodied, attitudinal, contextual, and other experiences that are constitutive of any usage event. Within this complexity of conceptual and situational resources, not all elements are activated with equal prominence. In every communicative event, participants are joined together in their common focus on the conceptual entity being designated by a linguistic expression, and which is referred to as the expression’s profile or its onstage region of conceptualization. Meaning, then, is said to reside in the tension between what is verbalized as the profile and the so-called base, which represents the profile’s background, where all sorts of conceptual elements linger with different degrees of prominence. Among the elements of the base, the so-called offstage region gathers those conceptual entities that are the most prominent ones in the background and thus immediately conceivable during a usage event (Langacker 2008, p. 77; Feyaerts 2013, p. 206). Depending on all sorts of situational and personal circumstances, gesture, mimicry, prosody and many other things, the same formal utterance may mean different things as in each usage event a different conceptual background may be highlighted. It makes quite a difference indeed whether an utterance like for this I need my red pencil pertains to an evaluative situation in a classroom, or a pen that looks red on the outside, but writes in black ink, or to a ritual-like habit for writing down the negative revenue of one’s business at the end of the month, or a reference to an oversized souvenir pencil with kitschy Lenin-decoration from my trip to the Soviet Union in the early eighties of the previous century etc. In all these usage events, the same wording is being used and reference is made to a pencil, but its relation to different conceptual backgrounds leads to different meanings in each of these usage events.

2.1.2. Engaging the Communicative Ground

Among the many elements that constitute an expression’s meaning there is one conceptual dimension, the so-called communicative ground, which in the context of this paper requires specific attention. As the central aspect of any utterance, the ground consists of the communicative event itself, including all participants in their roles of producers or receivers/consumers of a message, the specific temporal and spatial circumstances of a usage event as well as the symbolic structure of the utterance itself in terms of its form/meaning pairing (Langacker 2008, p. 259). Under unmarked circumstances, the ground and object of conceptualization figure in a highly asymmetrical relation since “subjects are mostly submerged in the process of conceptualization, focused on the object of conceptualization and hence not aware of their role as viewers or conceptualizers” (Feyaerts 2013, p. 208).

Regarding the specificity of the data in our present paper, the relative prominence with which the ground is represented as part of the object of conceptualization will prove to be a distinctive feature in our empirical analysis. Under regular, non-pandemic circumstances, messages in and on shop windows are not only scarce but also small, leaving as much free surface on the window as possible in order to allow maximal and undistracted visual contact with the products on the inside of the shop window. Further, normally, the few messages that do appear on shop windows hardly show any traces of the ground, restricted as they are to announcing product-related or practical information like price offers, brand logos, opening hours and closing day, a no-dogs-allowed sign, obtained quality labels etc. Apart from obvious counter examples like taglines underneath brand names, positioning the companies as family businesses (Fourth generation of shoemakers) or publicity campaigns that call to action (Come in and share our excitement!), elements of the ground like the message’s producer and addressees are excluded and kept at maximal distance from the object of conceptualization, thus allowing only minimal, if any, awareness of their presence. As a result, by default people processing conventional shop window communication, either as producer or addressee, are largely absent from the conceptual structure of the corresponding usage event, as their presence might blur the envisaged clear alignment between potential customers and the products on display.

In our daily communication, we constantly make use of grammatical and lexical elements to connect the content of our utterances with the ground. Think of the use of tense morphemes to specify a temporal reference point or the use of the definite article (the product) to indicate familiarity, and thereby establish an implicit link with the speaker. For various communicative reasons, as the examples in (1)–(3) show, elements from the ground can be dragged towards or even into an expression’s conceptual profile (or ‘onstage region’) with even greater prominence. In (1) the modal verb must turns the utterance into an epistemic predication, revealing (but not explicating) the producer behind this utterance as the source of this cognitive process of deduction. In (2) the pronouns we, you and our openly refer to participants assumed to take part in this trading interaction, even when the referential meaning of these elements is generic (we as sellers, you as customers). When displayed in a shop, the pronoun us in a call to action like (3) puts the staff (employees or owners) onstage as a prominent (and visible) part of this utterance’s meaning. We will refer to the latter construal operation, in which an element from the ground is brought onstage and thus verbally coded as in (2)–(3), as objectification. Cases in which elements from the ground clearly enter the offstage region of the conceptually prominent elements without however being verbally sanctioned, as in (1), will be characterized in terms of the construal operation subjectification.

- She must have seen how it happened.

- We want you to come in and smell our coffee.

- Looking for a different color? Ask us!

2.1.3. A Socio-Cognitive Model of Meaning

From the previous description one might draw the conclusion that in cognitive linguistics the process of meaning construal is an individual matter with a single participant ultimately deciding how an experience in a particular usage event will be represented hence interpreted. Although traditionally the social dimension of interaction was relegated to the periphery in cognitive research (Barlow and Kemmer 2000, p. ix), nowadays studies in cognitive and interactional linguistics explore both the cognitive structure and the interpersonal dynamics of a usage event, commonly referring to it in terms of intersubjective aspects of meaning (Langacker 2001; Verhagen 2005, 2008; Dancygier and Vandelanotte 2017, among others). According to a socio-cognitive model of linguistic analysis, meaning involves a constant coordination process among interlocutors as members of the ground (Brône 2010, p. 399ff). People engaging in interaction, be it a face-to-face conversation or a distant written exchange, do not produce their utterances in a social-interactional vacuum, but design them for an addressee.

This socio-cognitive view identifies language use, both in terms of production and interpretation, as a constant process of intersubjective coordination among interlocutors. Clark (1996) describes it as a joint activity comparing it to dancing a tango: dancers like interlocutors need to be able to adjust to their partners as much as they both need to be able to anticipate their partners’ movements or utterances (Feyaerts 2013). This mutual coordination process very much relies on what interactants assume to be in the hearts and minds of their interaction partners, the so-called common ground (Clark 1996), so that they can align their construal with it. Communicative interaction can therefore be characterized as a process requiring constant alignment and negotiation among intersubjective viewpoints. This view on intersubjectivity is very much in line with the theory of mind (Whiten 1991; Givón 2005), which evolves around our ability to conceptualize thoughts, ideas, emotions, attitudes, beliefs etc. in other people’s mind (Brône 2010, pp. 91–92)1. This intersubjective take at any stage of the communication process is of major importance for an adequate analysis of our dataset. With regard to the specificity of our data, we will demonstrate that, much in parallel to expressions of creativity (Feyaerts 2013; Veale et al. 2013), most of the COVID-related shop window messages are (like) stance-taking acts, the interpretation of which integrates construal processes of objectification and subjectification into a subtle choreography of intersubjective meaning coordination, in which multiple elements of the communicative ground are engaged. With respect to the paradigm of linguistic landscape research, this perspective on the relatively prominent construal of elements of the ground in messages like these tackles one of the new, yet still under-investigated research topics in the field, where only a “very limited number of studies focus on cognition” (Shohamy 2018, p. 35).

2.2. Modelling Business Personas in Marketing

One of the major questions in modern professional marketing advice concerns the strategic adaptation of so-called buyer personas, which are commonly defined as highly elaborated, semi-fictional mappings of a business’ ideal customer(s) (Revella 2015; Bianchi 2015). Interviewed by J. Harris (2020), Adele Revella, CEO and founder of the Buyer Persona Institute, specifies that these representations are based on market research, select educated speculation and real data about a company’s existing customers. Since they are supposed to tell the story of the dynamic behavior patterns, shared pain points, and universal goals of a company’s potential and customer(s), buyer personas cannot just be reduced to traditional static (sub)categories labeling target markets or specific real people. Developing buyer personas—if necessary, more than one within a single firm—helps companies to get into the mindset of their prospects to attract and reach them in the right way (Chemko 2016; Lee 2017; Dongleur 2020; Arts 2018; von Schmeling 2020; Phelan 2020).

2.2.1. A Pin-Up on the Wall

In the early days of the new millennium the concept of a buyer persona entered the world of commerce—its foundation and methodological elaboration being claimed by strategists like Tony Zambito. It was designed to assist businesses in keeping a close eye on their target market(s) on the background of ever-changing economic and societal circumstances. In 2013, a now widely quoted study (Sutton 2013) by MarketingSherpa into the impact of a targeted persona strategy revealed an increase of sales leads by 124% for companies engaging in this type of marketing research. Among the explanations for this success rate and therefore also the major reasons why companies should be engaging in this kind of strategy, experts indicate that having access to elaborate and quarterly updated customer profiles adds a huge amount of agility to one’s business allowing to make fast and well-founded strategic decisions, aligned with changing circumstances. Companies willing to develop one or more buyer personas are required to take multiple resources into account including market studies but also data from interviews and questionnaires involving real and potential customers. Moreover, in order to get a realistic and sustainable access to customers’ habits, attitudes, motivations, concerns, frustrations, intentions and goals, a buyer persona must become what it pretends to be, which is a ‘real’ person characterized by all relevant features one can think of. Accordingly, companies are invited to construe for every of their buyer personas a full-fledged personality, including information about their gender, education, generation, age, style, hobby’s, political preferences, aversions, etc. right up to a name and even a visual representation in a picture, ready to be used as an omnipresent pin-up in the office space. Importantly, dressing up a buyer persona should not be limited to a static inventory of personality features along with a focus on the specifics of the products or services to be sold. Of even greater importance is the contextualization of these features in the buyer’s so-called customer journey (Alvarez et al. 2020, pp. 5–8), which maps all possible ‘touch points’ a business might have with the customer. This constructed, empirically grounded journey consists of multiple scenarios, in which the buyer persona is actively involved, as they occur at various stages of the commercial transaction process. It leads from the buyer’s preparatory scanning of the market (Where do people gather information? Which communication media do they use?) over the circumstances, in which the purchase is embedded (Which sources of information do people use in the period leading up to the purchase? In what type of shop do people buy our products?) to questions about what products and services the buyer persona prefers or avoids, where their loyalty lies, which goals they pursue etc. (Arts 2018). Interestingly for the purpose of our study, the process of developing an adequate buyer (or seller) persona as an idealized, empirically grounded depiction of one’s business partner(s), represents a highly elaborated and successful application of the aforementioned ‘theory of mind’.

2.2.2. Pandemic Advice: Humanize Your Business

Already at an early stage of the pandemic, marketing researchers agreed that “the COVID-19 pandemic represents one of the most significant environmental changes in the modern marketing history, which could potentially have a profound impact on corporate social responsibility (CSR), consumer ethics, and basic marketing philosophy” (He and Harris 2020, p. 176). Vis-à-vis the unprecedented impact of this crisis on every sector in our society, marketers appealed to entrepreneurs and shop owners to seriously reconsider their business communication along with (some of) characteristics of the business personas. In order to stay aligned with shifting social, emotional, and commercial attitudes favoring local, online, and sustainable shopping, businesses were advised to abandon rigid content-centered sales strategies and take the face, instead, of a seller persona who, among other things, reaches out on a social level, for instance by genuinely engaging with customers’ personalities, problems and needs (Majercakova and Rostasova 2021, p. 2). Accordingly, regarding the market’s unpredictability in the first months of this lockdown period, entrepreneurs were told to build trust, credibility, and authority in the relation with their clients (Tom Wardman, 17 March on the blog of MMGrowth). In her blog entry for Fronetics on 19th May, Ulrika Gerth (2020) summarized her advice in a powerful way: “Humanize the company (…) Think tactful and empathetic. Stay active and engaged”. A scan through the advice of several marketing blogs during the months March–June 2020 about how to adjust business personas, pictures a clear tendency towards adopting an empathetic and human-inspired marketing and communication strategy. A year later, these early views appear to have further stabilized in mainstream marketing research. On 10th March 2021 in the Harvard Business Review, Balis (2021, p. 8) projects as one of the outcomes of the crisis “a mindset of marketing agility that is likely to be permanent. This includes continuous consumer listening and demand sensing, not only for the benefit of marketing but for the full company to capture the zeitgeist of consumer sentiment.” Next to quality, convenience and price as relatively stable consumer factors, she notes that features like “sustainability, trust, ethical sourcing, and social responsibility are important to how consumers select their products and services” (Balis 2021, p. 8). In light of a large-scale Kantar (2020) survey, which reveals that no less than 92% of the customers expected firms to continue advertising during the COVID-19 pandemic (Demsar et al. forthcoming, p. 5), businesses are warned not to drop their marketing activity completely during a major crisis like this. Instead, they need to maintain their brand’s voice and presence, be it in an adjusted and more agile, customer-oriented way (Ross 2020, p. 30).

Along with the observations of marketers being able to give adequate advice based on early readings of new societal trends and developments, the major hypothesis of this study was that compared to pre-COVID days, communication by shops and other businesses during the first lockdown of March and April 2020 was expected to profile less product-related content while at the same time unveiling more of the human characteristics of every business participant. In more technical terms of the construal operations involved, according to this hypothesis we expected to find mechanisms like subjectification and objectification operating quite frequently on elements of the communicative ground, drawing one or more participants and/or aspects of the message itself towards or even into the onstage region of conceptualization. For the domain of business communication, any empirical evidence for this would amount to further investigating the sustainability of this phenomenon in terms of a new trend or even a ground-braking shift.

In the next section, we take a closer look at our data. First, we describe the features of the data set, after which we focus on the analysis of a selection of eighteen examples.

3. Data and Method

The empirical part of this study is based on a small data set of about 30 authentic pictures taken in the Flemish city of Leuven during the first period of economic lockdown between 13th March and 13th May 2020. Over these two months regular life came to a standstill, people and companies had to work online, schools were closed for several weeks offering online teaching, and pubs, restaurants sports infrastructure as well as all non-essential shops and businesses were kept closed. The pictures we analyze here focus on the messages, which soon after the lockdown was installed, started appearing on and inside shop windows. Right away, many of them expressed messages of personal involvement, empathy, and concern, hardly referring to products and business and as such revealing a distinct perspective compared to pre-pandemic commercial communication. Apart from shop owners and employees exposing themselves, passersby reading these messages may have wondered what person or instance was behind them, who could be meant as addressee and how the unusual message should be interpreted properly. Already these reflections taken by themselves, as the very fact that questions are raised about the identity and the role of the participants in this communicative exchange, reflect a major shift in the construal constellation of this type of communication. Moreover, in this respect, quite a few messages, especially those appearing in small autonomous shops during the first weeks, appeared as messages with a high degree of self-made or vintage craftmanship: messages hand-written or home-printed on household writing paper, attached to the window or some object inside the shop using adhesive tape etc. (see also Ramjaun 2020 on visual COVID-related communication in UK retail outlets). These striking material characteristics draw attention to the message as such, which by consequence is then conceptually staged as yet another element of the communicative ground. Although we realize that we base our analysis on a very limited set of data points, our specific interest in documenting and analyzing the aforementioned qualitative aspects of this humanized commercial communication motivated us to adopt a close-reading description of these very first tokens, which inevitably were scarce and had to be hand-picked on walks through the city.

4. Empirical Analysis

Considering the observations made above, we now present a series of pictures of shop window messages, whose analysis will demonstrate in what ways these early lockdown messages align with the marketing advice to humanize one’s company. At the same time, we dig into the various specific construal constellations a linguistic analysis of these messages will reveal.

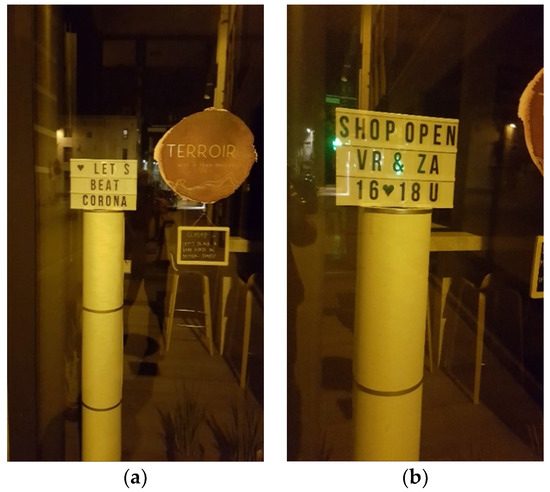

A first picture (Figure 1a) shows an English message Let’s beat corona together accompanied by a heart-shape symbol2, as it appeared in a Leuven delicacies shop. The second picture (Figure 1b) is taken a few months after the lockdown, and it demonstrates how the message in (Figure 1a) was created on the same spot using the same material elements as in pre-COVID times the shop’s opening hours were announced. Already this first example nicely illustrates the marked character of this shop-based interaction, in which no commercial message is being communicated. Instead, the one-liner appeals to passersby through its human message of combativity and caring solidarity—symbolized by the heart shape at the beginning—against corona as the common enemy. Next to the reinterpretation of the communicative space and materialities, this non-commercial content is another aspect of incongruity, which inevitably draws attention to the communicative situation itself (Who produced this? the shop owner? an employee? Is it meant for me?). Through both incongruities and especially the interpretational effect of de-automatization that comes with them, the communicative ground is drawn towards the onstage region of conceptualization. The use of the enclitic pronoun (u)s provides the clearest illustration of this process of objectification.

Figure 1.

(a,b): Let’s beat corona.

The picture in (Figure 2) shows a note which is taped to a terrace fence just outside a restaurant. Unlike the previous example in (Figure 1a), the message itself, which informs about the restaurant’s closure but also about the possibility to buy take-away dishes as of 16 March, is quite neutral and unmarked in this commercial context. In terms of marketing strategy, it does comply with the advice to engage with the customers on the level of general human needs. The negative message about being closed is cleverly countered by the announcement of the take-away dishes, which already at the earliest stage of the lockdown meets the customers’ needs. What stands out in this message, rather, is the improvised material character of the note, which is a home-printed message, taped to the glass of the terrace fence with one corner of the paper coming off. Along with the typographic highlighting of positively connotated words (especially the adverb gelukkig (’luckily’) and the adjective heerlijke (‘delicious’) next to meeneemgerechten, the Dutch equivalent for ‘take-away dishes’), these characteristics draw people’s attention. As far as the participants are concerned, apart from the customer being addressed explicitly by the pronoun u (polite variant of ‘you’) as part of this regular commercial announcement, no construal of the communicative ground can be noted.

Figure 2.

The restaurant will be closed until 3rd April. But luckily starting from 16 March you can drop by for delicious take-away dishes.

The following picture is another illustration of the way, in which shops have improvised about the way to communicate with their customers during the first weeks of the lockdown period. In (Figure 3) we notice a four-fold message by the local Neckermann traveling agency, which is printed on four separate A4-pages and then visibly taped one right next to the other on the shop window. The result is a remarkable mixture of slogans (dream with Neckermann; we are ready for you), practical information (e-mail, URL, telephone number), wordplay (sea/see you soon), symbols (hearts, flower leaves), an emotional one-liner (we have a heart for you) and all of that in different typographic styles, colours as well as font types and sizes (see Stöckl 2005; Forceville 2020, among others, on the relevance of analyzing the visual dimensions of the written-verbal mode). As such this communicative assemblage draws immediate attention as an overdone customer-oriented reaching-out. It seems like every employee in the office could put up their personalized message with this uncoordinated result in the middle of the shop window. In terms of construal, both the message’s material form and inconsistent content make the communicative message in all its aspects to an object of interpretation. Along with it comes the inevitable question about who acted as the producer(s) of this communication, embedded in some sort of stance-taking act through which the message is evaluated as more or less appropriate and successful. In three one-liners, finally, the potential customers are being objectified as addressees using the deictic pronouns je/jou (the informal object-forms of the personal pronoun je (‘you’) and even the English pronoun you).

Figure 3.

Sea you soon.

Figure 4 shows an extreme example of the way in which shop owners, in this case of a sandwich shop, may humanize their business by reaching out in solidarity to other people outside the shop. The message consists of a drawing made and captioned by a child showing two cheerful figures separated by two arrows and one of them asking the other to stop at 1.5 m. The caption above reads as Keep enough distance while the one below the picture is essentially commercial, as it promotes good lunch and then mentions the name of the shop (de Pandora). All letters are in multiple colours. The A4-page with the message on it is taped to the glass of the shop window. In this hybrid message, in which the business-related information looks sweet-awkward, the shop owners reveal themselves as parents of a child thus downplaying their institutional role as sellers in a commercial transaction. Through this drawing, all participants of the communicative ground, which include the shop owners putting up this message as well as the passersby reading it, are being highlighted—yet without any verbal objectification—as part of the conceptual structure of this semi-commercial communicative act.

Figure 4.

Keep enough distance.

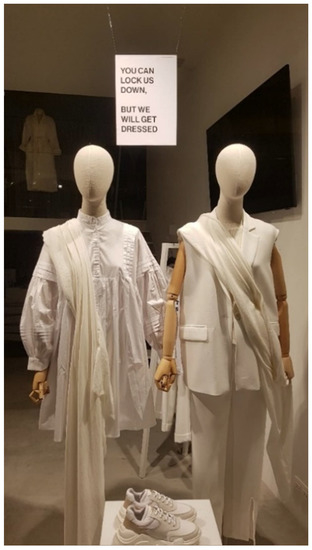

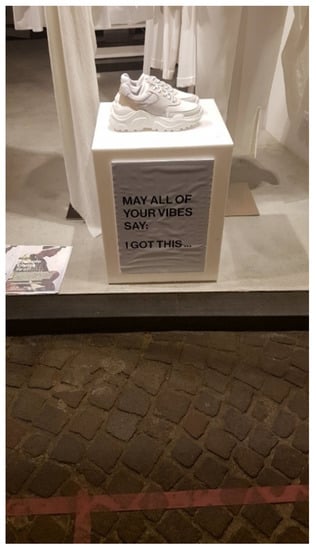

As the following pictures show, putting more than one message on display does not necessarily lead to material, stylistic or content-related chaos as in (Figure 3). The Figure 5 and Figure 6 were taken on the same day of the same shop window. Both messages share the same language (English), style, colors, font type and size, paper format as well as the hardboard onto which the A4-page is glued (see, among others, Stöckl 2005; Forceville 2020). Apart from the enclosed air bubbles below in Figure 5, giving away its status of a handmade item, the messages look quite professional and well-designed as they blend in nicely amidst the white tones of the shop interior. So, as far as formal and material features are concerned, these messages do not draw any specific attention to their producers. When we look at the wording, it is striking that both messages are expressed in English, which may deviate from pre-pandemic rules and circumstances, and which may be an indication of the generic, humanized character their meaning was intended to convey. More likely, however, may be that the use of English expresses a corporate marketing communication strategy according to which a buyer persona is a global citizen, who speaks English as a globally widespread lingua franca.

Figure 5.

You can lock us down, but we will get dressed.

Figure 6.

May all of your vibes say: I got this…

Regarding their content, these messages clearly differ from the unmarked commercial discourse a shop window would require under normal circumstances. In their reference to the actuality of the lockdown, both slogans depart from regular commercially driven shop window communication. In both cases their expressive meaning hinges on a perspectival shift, in which one or more deictic elements are involved, but which clearly differ from one another (Dancygier and Vandelanotte 2017). In Figure 6, the possessive pronoun your is embedded in a powerful wish expressing inner strength and self-control thus orienting the message at anyone reading it. Within the message another perspective is adopted as I got this implies taking on the perspective of the person referred to in the first part by means of the possessive pronoun. Passersby reading this message can hardly avoid interpreting it as being aimed at themselves and by consequence feeling highly involved in it3. In that plausible sense, both the possessive and the first-person personal pronoun operate as a grounding predication through which especially the customer as addressee is brought onstage. In case of the possessive pronoun, the addressee is explicitly mentioned and therefore put onstage in the conceptual scene, along with, by implication (who formulates this wish?), the shop owner as this message’s assumed producer. In the case of using the pronoun I as part of the direct speech in this quoted utterance, the customer is objectified as the idealized agent of an (also idealized) desirable action.

The slogan in Figure 5 also involves the deictic pronoun you as in Figure 6, yet here it serves another function as it refers to the national authorities imposing the lockdown. More interestingly though, depending on the interpretation of the first-person pronouns us and we, this scene can be interpreted in two ways. A first reading arises from the interpretation of both pronouns as referring to ‘every citizen’. The mannequins, then, metonymically4 stand for the population as a whole, their missing faces emphasizing that the referential meaning does not align with them but, rather, with other entities beyond them. What this scene depicts, then, is the mannequins acting and protesting on behalf of the entire population as it were.

Yet, a second interpretation is plausible as well. In order to get that right, we need to get a closer look at the local constellation in which the verbal message is being displayed. Of crucial importance is the immediate proximity of the message to the two mannequins, which upon closer inspection, appear to pose hand in hand. Because of this direct proximity, the semi-concessive, provoking message (you can lock us down…), can also be interpreted as a materialized text balloon thus aligning the referential meaning with the (personified) mannequins themselves, who ultimately might be seen as metonymically standing for the shop owners. Further, in this multimodal link between the message and the mannequins, the second clause (we will get dressed) still makes perfect sense: even in closed fashion shops, mannequins (we) get dressed. What we see here, then, resembles a screen shot or a panel in a comic, whose interactional dynamics is driven by the text balloon.

In either interpretation, the construal of the mannequin as an acting person, gaining identity and protesting for being locked down by the government, involves a personification metaphor. Moreover, in both interpretations, the message motivates the marked pose of holding hands as a symbolic gesture of solidarity, the mannequins metonymically standing for either ‘their’ shop owners or for all people being shut down. The entire scene appears as a subtle interplay of different perspectives and other construal operations being integrated into a highly intersubjective scene, which appeals to at least three strong feelings of human involvement. First, the scene expresses solidarity among all people struck by the lockdown, second, the concessive clause expresses a subtle protest against the drastic measures that were taken, and third, the wish in the second message sends out a message of encouragement. Overall, the messages in this shop window engage in a remarkably diverse and sophisticated manner with all humans behind the participants of the commercial transaction process. In doing so, here also the communicative ground has taken center stage in the interpretation of this interaction.

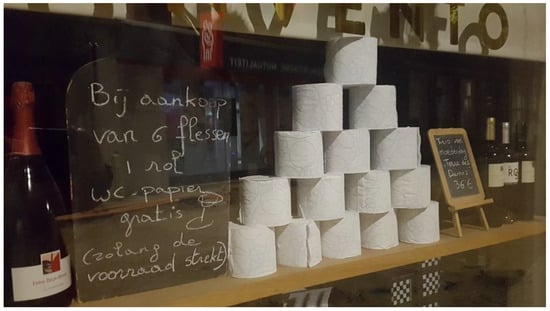

Whereas the previous examples have revealed a good deal of creativity involved in the production of these messages, the picture in Figure 7 comes with plain humor. Very prominent in the middle of its shop window, an exclusive wine shop has a pyramid of toilet paper rolls on display along with a hand-written message on a chalkboard promising one roll of toilet paper for free upon the purchase of six bottles of wine. The motivation behind this incongruous juxtaposition of wine and toilet paper lies in the earliest days of the lockdown period, when people feared supply chains would break down leading to shortages of consumer goods. As a consequence, people started hoarding all kinds of basic goods, the most iconic and mediatized example of which are images (later on memes as well) of people leaving supermarkets with huge amounts of toilet paper. The discrete comment at the bottom of the chalkboard (while supplies last) is a subtle reference to this irrational behavior. On the background of this situation, the incongruous display in this shop window reads as a strong parody, which is a quite unusual phenomenon to encounter in the context of a business.

Figure 7.

One roll of toilet paper for free when you buy six bottles of wine.

As with all types of interactional humor, the look of toilet paper in a wine shop heavily de-automatizes the regular interpretation process of customers and passersby interested in the goods this particular shop has to offer. As a consequence, people inevitably wonder how this particular set-up ought to be interpreted and, also, who may have come up with this humorous act. As such, these considerations clearly mark a shift of the communicative ground towards the center of the interpretation process, where it becomes part of the conceptual structure of this communicative exchange. In technical terms of the construal operations involved, since no element of the ground gets verbally coded in this scene, the conceptual constellation qualifies as an example of subjectification. Addressee (and producer) very much become aware of their respective roles in this communicative exchange, also questioning and mutually evaluating them and as such making that reflection a prominent part of the process of meaning making.

In this respect, the introduction of humor in this business-related setting qualifies as a stance-taking act (Feyaerts et al. 2017), which can be described as a prototypical process of intersubjective meaning coordination. In embarking on humor in this context, the shop owners heavily rely on their assumed common ground that most or even all passersby will experience a positive appreciation in response to interpreting the scene in the shop window.

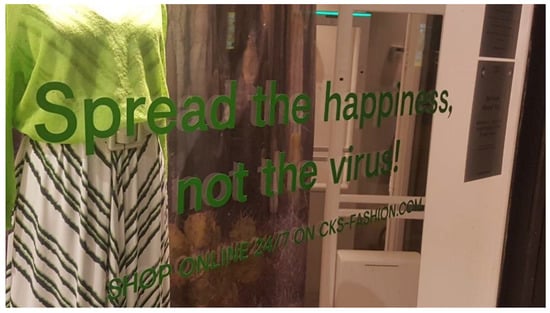

The examples discussed so far all express a high degree of DIY craftmanship, which especially becomes clear in the materials that were used for producing and displaying the message. However, this observation does not hold true for all the messages that surfaced in shop windows in this period. Based on our limited data corpus, we had the impression that the further we got into the lockdown, the more professionally looking messages appeared. A nice illustration is the message in (Figure 8) on the window of this fashion shop. It is a hybrid message with both socially sensitive and commercial content, whose relative position to one another along with the different font sizes gives a clear indication of the relative prominence of each content type. The human-interest message, in English, appears on top in the biggest and bold font size, closed by an exclamation mark. Below it, smaller and thinner comes all practical information about online shopping (shop online 24/7 on cks-fashion.com). Overall, the message looks quite professional showing no flaws in either positioning, materials, style, or colors. The content of the message is a powerful call-to-action as well, encouraging people to cheer up (individually) without contaminating each other. The use of the imperative in combination with the exclamation mark grants the one-liner an even stronger interpersonal appeal. The message directly addresses every passerby, clearly pulling the ground into the so-called offstage region of the conceptual structure. Since no element of the communicative ground is being verbally coded, this construal operation would qualify as an instance of subjectification.

Figure 8.

Spread the happiness, not the virus!

Interestingly, next to this generally human interpretation, which is accessible to everyone, the message in (Figure 8) also appeals to the regular customers of CKS-Fashion in a specific and refined way. The call-to-action on the shop window is creatively construed around the brand name’s tagline Happiness is a way of life, which is at the core of the company’s transformational (or expressive) positioning strategy, along the lines of which CKS-Fashion does not primarily sell fashionable clothing, but happiness instead5. In light of this strategy, the message on the shop window appeals to this element of common ground, which is shared with the (regular) customers, thus acquiring a different, more coherent and also more commercially profiled reading. In this perspective, then, the use of the definite article the, which is normally used to ground an element in its intersubjective status of being known or familiar to both producer and receiver of a message, becomes fully transparent as it clearly refers to the aforementioned tagline. Anyone familiar with CKS-Fashion knows which happiness is being referred to. Accordingly, the message in its entirety now coherently reads as an encouragement to ‘Continue spreading ”our” happiness (…) by shopping online at the following internet address…’, suggesting that the ‘people around you will get contaminated by your happiness, which is achieved by you wearing our clothes…’. All in all, in this message CKS-Fashion nicely demonstrates the fine art of elegantly integrating the key notion of one’s long-standing commercial strategy into a situationally pertinent, wordplay-like message of general human concern.

Another example of a professionally designed message expressing basic human values is the heart-shaped sticker in Figure 9 saying Together we stand stronger. Because of the corporate color as well as the #JBCfamily company hashtag this sign also has a hybrid character (see, among others, Stöckl 2005; Forceville 2020 on the role of visual elements in multimodal analyses). Compared to the previous example, the emotional content in (Figure 9) seems to be construed a bit stronger because of the heart-shaped sign as well as the inclusive pronoun we, thus putting the communicative ground onstage. At the same time the commercial information is presented relatively weak here. The sign does mention some practical information about the shop’s opening hours as well as information about online shopping alternatives. However, quite subtly, the #JBCfamily hashtag adds a business-related equivalent of the message of togetherness to the message. In connection with the company name, the ‘family’ concept operates as what marketers label a ‘community-building’ feature, which is to be understood as the buyer and seller community gathered under the JBC label. Because of its relative appearance, lower, shorter, and smaller than the general message, the commercial meaning clearly stands back as secondary, but it is there already, and it finds itself elegantly embedded in the bigger picture of human concern.

Figure 9.

Together we stand stronger.

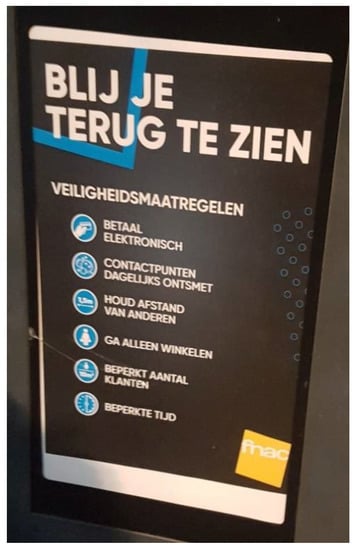

Once the announcement was made, after a few weeks into the lockdown, when businesses would be allowed to reopen, many shops, most of them bigger companies, anticipated this moment with messages welcoming all customers back. The Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18 show some of the variations, by which customers were greeted back. Whereas some of these messages highlight the shop keeper’s endured emotion of ‘having missed’ the customers, as in Figure 12 and Figure 14, most of the messages express the interpersonal perspective of ‘welcoming back’ everybody. All messages reach out to passersby expressing a human desire to reconnect. In some cases, the verbal message is supported by visual elements like the heart shape as a symbol for love in Figure 11 and Figure 16 or the smiling faces of real people (Figure 13) or brand-related characters (Figure 16). Some have a hybrid character as they juxtapose welcoming words with business-related information like security issues as in Figure 14 and Figure 15, or price reductions as in (Figure 12). Another variable in the realization of this message concerns the prominence by which the addressees as well as others are included in the message. In most cases, addressees are mentioned explicitly by the deictic pronoun you or its Dutch informal equivalent je as in Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 17 and Figure 18. In a few cases, this deictic reference is accompanied by the first-person plural pronoun we, as in Figure 12, Figure 14 and Figure 18, which puts the perspective of the humanized seller persona onstage, at the center of the expression’s conceptual structure.

Figure 10.

We meet again! Please do come in.

Figure 11.

HEMA Welcome back.

Figure 12.

Welcome back, we’ve missed you!

Figure 13.

So good to see you again!

Figure 14.

We have missed you!

Figure 15.

Happy to see you again.

Figure 16.

Welcome back! From Woody with love.

Figure 17.

Happy to see you again!

Figure 18.

You’re back We’re back Happy to #reconnect.

The pronoun we is also present in Figure 10, yet not with the same referential meaning as in the cases mentioned so far. Here, as the subject of the verb meet, the pronoun we refers to both perspectives involved in the (commercial) interaction. The line in Dutch (kom gerust binnen), which can be paraphrased as ‘feel free to come in’, directly appeals to the customer—not mentioning them though—in a very inviting and comforting way using the down-toning particle gerust in combination with the imperative. Finally, the English opening line of this message, which was put up at the door of the same fashion shop already discussed for the examples in Figure 5 and Figure 6, may be containing one final intertextual wink as We meet again! seems to evoke the historic one-liner and song title by British singer Vera Lynn—We’ll meet again—and which enjoyed a media-driven revival during the lockdown period of Spring 2020.

One final observation in this subset of welcoming messages concerns the language being used. Of the nine cases presented here, four are entirely in English (Welcome back, we’ve missed you! So good to see you again! Happy to see you again! You’re back, we’re back, happy to #reconnect!) while in three additional messages—Figure 10, Figure 14 and Figure 16—Dutch is being mixed with English, leaving only two entirely in Dutch. This observation is in line with what we have seen in the other messages as well. Of the nine pictures already described before this welcoming subset, five were (partially) in English.

5. Discussion

In the previous chapter we have presented eighteen examples of the way in which companies, shop owners and employees have dealt with the unprecedented situation of being locked down with their business. Despite the limited set of data, the close-reading of the examples in our study revealed some interesting preliminary findings about what appears to be a shift in the nature of the on-site communication of local shops during the first 2020 lockdown. Interestingly, our findings show remarkable parallels with the results of similar small- and medium-scale case studies for Hamburg (Androutsopoulos 2020), Bournemouth (Ramjaun 2020) and Vancouver (Dancygier et al. forthcoming). In particular, all studies reveal a new type of humanized business communication involving both linguistic (like modal, deictic etc.) and material phenomena (like non-professional design and production etc.) as well as corresponding content messages, through which contextually ‘atypical’ messages of interpersonal, empathetic relations are being expressed.

At this point in time, more than a year after the outbreak of the pandemic, it looks like the phenomena small case studies like ours have documented, were the first signs of a major change, which is about to leave permanent traces in current and future marketing strategies and business communication. In light of the growing impact of digital and remote transaction formats—a development which had already started before the COVID-19 crisis but now has generated strong and global momentum (Demsar et al. forthcoming, p. 7; Clapp 2020)—the market share for offline sales is gradually diminishing. By consequence pressure on shops and businesses operating in this shrinking segment increases to dramatically step up their marketing agility and consumer-oriented efforts in an attempt to remain in touch with their core customers (Sheth 2020). On the ground this means facing the challenge of ever more frequently updating customer segments and buyer personas (Balis 2021, p. 2): “brands must communicate in very local and precise terms, targeting specific consumers based on their circumstances and what is most relevant to them. (…) [M]arketing messages need to be personally relevant, aligned to an individual’s situation and values, as opposed to demographics, such as age and gender.”

In line with these observations, our close-reading analysis has revealed a great deal of creative variety among the different messages on shop windows. This could be observed most clearly in the messages that were put on display in the smaller shops and also during the earliest weeks of the lockdown. In that sense, our data, limited in number as they may be, tell a more nuanced story than the “sea of sameness” pictured by Demsar et al. (forthcoming, p. 9) about advertising in times of COVID-19 as being “all so laughably similar” (Diaz 2020). Although on a high level of schematic description, from where at a later stage in the pandemic one might look back at the numerous occurrences of particular words and slogans (‘unprecedented’, ‘we’re all in this together’) thus discovering quite a lot of similarity (see also Dancygier et al. forthcoming; Ramjaun 2020), a case-by-case analysis of the both situationally and contextually embedded usage-events reveals a more subtle picture. Indeed, a great number of shops and businesses exhausted themselves in expressing overall human values like solidarity, empathy, comfort etc., which in the light of the global ‘unprecedented’ pandemic might not even be too surprising. Yet, it may be somewhat rushed to derive a conclusion about customers’ qualitative judgements in terms of a negative experience like ‘boredom’ from an observation made on a highly schematic, decontextualized level of quantitative generalization. No real customer ever experiences all these similar messages together, materially detached and juxtaposed to one another. In that sense, the disturbing effect of observed ‘sameness’ may be held within analytical limits. Of course, as documented in our data analysis, a process of imitation may set in once bigger firms start the professional mass-production of humanized messages along the lines of their regular corporate colors and design. At that point, the ingredient of authentic creativity on the side of the shop owner or employee may get lost, possibly along with the interest or confidence on the side of the customer. In the light of that threat, we do side with Demsar et al. (forthcoming, pp. 5–9) in identifying a set of strategic, creative and media-related guidelines, which on the level of the production process may serve to secure positive alignment with the envisaged customer segment.

Through our focus on intersubjective aspects of construal (subjectification, objectification), we provide additional, linguistic technicality to this strategy, which at all times may be exploited in the process of creative communication (Feyaerts 2013). On the level of analyzing the marketing and communication strategies of the messages that have already been used on the ground, we believe that a close-reading of a relatively small set of tokens, situated within a single temporal and spatial unit of analysis (in our case, shops in Leuven in March–May 2020), provides a relevant complementary perspective to a more quantitively oriented method of data analysis. Only by descending on this basic level of descriptive analysis, we have been able to uncover a great deal of variation and evolution in these messages with regard to their content, the materials being used, the professionality of the production process as well as the conceptualized status of the communicative ground. Acting so has resulted in some sort of early-warning description, which apparently has been able to capture the first signs of what increasingly turns out to be a new trend or even a new standard in the field of strategic marketing and business communication.

On the background of the advice made by marketers to drastically ‘humanize the business’ and realign traditional content-centered business communication towards a genuinely human social exchange, this analysis has presented limited but clear empirical evidence for this communicative shift. All eighteen examples discussed above incorporate what may be labeled a new, probably temporary type of ‘humanized business communication’, which centers around an increased attention for the empathetic, interpersonal dimension of the business personae and their mutual interaction. As demonstrated by our examples, this shift can most clearly be observed on the content level of the messages themselves, which have been shown to express general human values like empathy (stay safe; …), solidarity (together we stand stronger), love (from Woody with love), greeting and welcoming (good to see you again), care (we’ve missed you), doing good (spread the happiness, not the virus), combativity (let’s beat corona), wishing-well (may all of your vibes say: I got this), happiness (happy to reconnect), hospitality (we meet again; feel free to come in), relatedness (#JBCfamily), mutual interaction (we meet again) etc. On the verbal level, deictic elements like personal and possessive pronouns which openly refer to participants in the communicative exchange, also trigger a more humanized, non-commercial interpretation of these messages.

The question how these examples relate to the marketers’ advice may not be that straightforward. In fact, there are two ways, in which the empirical validation of the central hypothesis may be motivated. A first and most probable explanation may be that our examples have brought to the surface what was already there in the first place, before marketers started collecting input for their advice. Our pictures, then, would be early original pieces of evidence, of the kind marketers stumbled on when investigating the circumstances to base their COVID-related advice on. On the other hand, second, some of the messages, especially the later and more professional ones, may have been produced by entrepreneurs and shop owners having learned about this humanizing market strategy and then complying with it.

Apart from the omnipresent topics on the content level as well as the objectification of the ground through verbal elements such as pronouns, the relative prominence of the interpersonal relation between the interaction partners also derives from other, communicatively much more subtle aspects of these messages. Unlike deictics, these phenomena do not directly profile elements of the ground in the onstage region of conceptualization. Instead, their unconventional and marked presence in the usage event leads to a de-automatization in the interpretation process, which in turn raises attention for the communicative ground, dragging (some of) its elements into the offstage region as a highly prominent yet not verbally sanctioned part of the conceptual structure. In our data we have encountered this construal mechanism of subjectification in multiple phenomena, through which various aspects of the communicative scene were highlighted.

A first illustration lies in the use of creative and humorous expressions or intertextuality, as three prototypical instances of linguistic elements with a layered meaning (Clark 1996; Feyaerts and Oben 2014, pp. 278–79). Both in the production and interpretation of these expressions, participants become aware of their mutual presence and interaction, wondering what their role as producers or interpreters in the communicative process, but also their status, actions and intentions might be. Both in producing and interpreting creative and humorous expressions, the ‘other’ participant is always very much present in the processing of the expression. A shop owner deciding to place toilet rolls next to exclusive bottles of wine will invoke some or most of their customers wondering whether they would appreciate them doing that. Passersby, on the other hand, will undoubtedly stop and wonder about the incongruous toilet rolls in the shop window and who would have gotten this funny, weird, or lame idea. Regardless of their specifics, it is the outline of these reflections towards the ‘other’ participant, which pulls the ground into the focus of attention.

Other examples of subjectification apparent in our data set involve lexical elements, which, again, do not make any direct reference to participants or other elements of the ground but instead evoke them by a strong association. So, if the JBC company uses the hashtag #JBCfamily in its welcoming message, as in (9), both sellers and—particularly—(potential) customers are gathered as all related and belonging to the same (commercial) family. Although nobody has been designated or pointed at, this community-building concept—along with the other verbal and visual elements—puts all parties involved in the offstage region of close attention. A similar effect is achieved using more functional and grammatical elements like (deleted) imperatives as in Welkom! Spread the happiness; kom gerust binnen; houd genoeg afstand etc., or downtoning particles like gerust in (10), which softens the imperative (kom binnen) from the speaker’s perspective, which in this case clearly coincides with the shop owner’s.

Apart from verbal elements, also material and circumstantial resources can trigger an interpretational shift in favor of a more humanized interpretation of business-situated communication. In our data, we encountered quite a few examples where a message was produced with materials that do not answer today’s standards of commercial shop window communication. The same observation holds true for the ways and places, in which the message was attached. Regardless of the specific realization, be it a child’s drawing or an improvised juxtaposition of four different messages, the unconventionality and markedness of these material and formal aspects lead to a de-automatization in the interpretation process as well, with people wondering and evaluating who might have produced these messages. Finally, the use of non-verbal elements like heart shapes or pictures of smiling people, or a curved line suggesting a smiley as in example 13 adds a multimodal dimension involving symbols and icons to the realization of this subjectification (see Stöckl 2005 and Forceville 2020 for an encompassing multimodal account of the visual dimensions of the written-verbal mode of expression). These elements as well enhance the conceptual prominence of the participants and their mutual relation as central elements of the communicative ground. Our focus on these subject-related construal phenomena, in which mostly only one of the participants, either the seller (or shop owner) or the buyer (or passerby) is involved, should not blind us for the fundamentally intersubjective nature of these construals. Shop owners figuring out the wording of a one-liner or putting up a particular sign do not just act by and for themselves in some interactional vacuum. Instead, in their commitment to the multiple elements in this production process, they actively construe a common ground with distant interlocutors, constantly elaborated by assumptions about what these customers and passersby might need, think, or feel etc. The same holds true for passersby observing and attempting to interpret these unconventional messages. They do not just absorb and interpret the message for themselves without also wondering who is behind it or taking some (dis)approving stance towards them.

Considering the advice formulated by marketing agencies about giving center stage to human values like empathy, solidarity and genuine interaction, the question can be raised, who the ‘participants’ are, who are being highlighted in this COVID-related communication: the business personas or, rather, the real human beings behind them? This may not always be easy to tell, but from the examples we have analyzed, it appears that the more a message expresses a hybrid character regarding product- or price-related content, or the more corporate colors and style are being used, the more business personas seem to be involved. However, when hardly any sign of commerce or publicity is involved, the more a message seems to breathe the characteristics of a real person behind the shop owner of employee. The examples with the child drawing in Figure 4, the failed coordination of four separate messages in Figure 3 or the toilet rolls in Figure 7 are optimal illustrations of messages, in which a real shop owner or employees are highlighted, which from a marketing point of view may not always be supposed to happen. Finally, as we have seen in the subset of welcoming messages in Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18, messages produced towards the end of the lockdown period tend to be more balanced in terms of their hybrid character: reaching out for people and empathizing with them while at the same time inviting them back into the shop.

6. Wider Implications

On a more theoretical level of linguistic analysis, the eighteen examples discussed in this context have made clear that an adequate analysis of this, like any, process of meaning making requires several types of resources to be considered. As such, the linguistic focus on verbal forms and meanings needs to be extended by a multimodal dimension, in which also non-verbal elements must be taken into account (see, for example, Stöckl 2005; Forceville 2020). In this type of distant, non-spoken interaction, the latter pertains to material aspects of both the message-as-object and the process of producing it. Moreover, the examples in our study have demonstrated that circumstantial aspects of time and place also are crucial dimensions of an accurate description of these usage events. It does matter where in the shop window or where relative to another message a message or sign is placed. The relevance of the temporal dimension is most apparent in the delineation of this new genre as being temporally bound by the prevailing conditions of the economic lockdown. Moreover, other temporal aspects like the lockdown’s approaching end seem to impact both the content and formal appearance of the messages with the commercial and professional characteristics regaining the shop as their natural habitat. Our analysis of the way in which different construal mechanisms (objectification, subjectification) are deployed in support of the envisaged interpretation of connecting with other people, demonstrates that an adequate analysis of meaning also requires the inclusion of the socio-cognitive dimension of intersubjective conceptualization, along the lines of which participants in an interaction model their contribution on the basis of different types of assumed common ground, linking them with their interactive counterparts.

Finally, considering its interdisciplinary nature, we look at the implications of this study for each of the disciplines involved, wondering whether both (cognitive) linguistics on the one hand and marketing analysis and business communication on the other benefit in any way from this cooperation. In the field of linguistics, our cognitive approach with its focus on the intersubjective articulation of construal mechanisms and therefore including the communicative ground as an inherent part of the analysis, meets the demand put forward in linguistic landscape research (Shohamy 2018) for integrating a socio-cognitive perspective in its research dynamics. Yet, by far the biggest impact of this study in linguistics concerns the overwhelming empirical support and ultimate instantiation derived from consumer-oriented marketing analysis for any model of intersubjective meaning coordination (Clark 1996; Langacker 2001, 2008; Verhagen 2008; Brône 2010; Feyaerts 2013, among others), according to which mutual assumptions about other people’s knowledge, intentions, attitudes and evaluations compose an inherent part of the interactive process of meaning coordination6.

With regard to marketing analysis and business communication, our study has shown that the field may benefit from the integration of cognitive mechanisms of intersubjective construal as a means to more accurately map the communicative ground as an essential part of any specific commercial usage event. Doing so will allow marketers and communication experts to arrive at a more fine-grained analysis of the ways in which any envisaged buyer persona or consumer segment may be optimally approached, thus avoiding the risk of being submerged in a sea of communicative sameness. On the level of empirical analysis, our close-reading of the shop window messages has captured the first signs of an augmented empathy-factor in business communication, which from the present point of view of marketing research appears to remain a powerful force in the process of adequately reaching out to customers, not just to sell products but to align with the human being behind the customer. With regard to similar future situations of commercial or societal crisis, the present project both in its method and interdisciplinary design, may serve as an inspiring pilot study for designing an early-warning survey modelling the degree, to which elements of the communicative ground move closer or onto the stage of conceptualization. It may turn out in future large-scale research that the degree, to which this conceptual shift happens, will be indicative of the strength by which a (commercial) society gets hit by a crisis.

7. Conclusions

This study engages with the advice formulated by multiple marketing agencies to drastically ‘humanize one’s business’ in order to be able to cope with the fundamental attitudinal shift that could be observed throughout society during the COVID-lockdown in Spring 2020. In the face of a common external threat, people got together and embraced social values like solidarity, empathy, and mutual support. Regarding business communication, this focal shift was expected to directly affect the relative prominence of otherwise hidden business personas, which would be profiled more strongly, as part of the object of conceptualization. Based on a small data set of authentic examples, we were able to empirically validate this expectation. Although the reliability of this study would benefit from a bigger dataset, we believe to have documented a new type of written urban communication, in which due to the restrictive measures that were taken to fight back the corona pandemic, shop windows were transformed into communication platforms for both transmitting and receiving messages of a genuinely human concern. This distant communication has all the characteristics of a glocal genre, in which a global societal crisis along with a global need to promote genuine togetherness among people, is creatively translated into both locally and temporally determined setting of shop window messages during the first lockdown in Spring 2020.

In order to be able to dig up the conceptual mechanisms underlying these expressions, we complemented the initial practical perspective of marketing research with the theoretical underpinnings of a cognitive linguistic analysis. Interestingly, both analytical paradigms converge in adopting a view which may be labeled as a theory of mind, according to which human beings are able to model someone else’s knowledge, thoughts, assumptions, feelings etc. Applied in the framework of marketing studies, this unique human ability is explored to the full of its potential. Apart from this socio-cognitive dimension, which directly pertains to enhanced prominence of the communicative ground, we have also observed the critical impact of both local and temporal circumstances like the materials being used, the position with regard to other elements in the shop window, the point in time a message appeared just like the duration of being displayed etc., onto the interpretation. In sum, this study has empirically demonstrated the necessity of taking into account a broad range of situated resources, which are brought to bear in the process of meaning making underlying these unique messages of empathetic business discourse.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.F. and G.H.; methodology, K.F.; validation, K.F. and G.H.; formal analysis, K.F. and G.H.; investigation, K.F. and G.H.; resources, K.F. and G.H.; data curation, K.F. and G.H.; writing—original draft preparation, K.F.; writing—review and editing, K.F. and G.H.; visualization, K.F.; supervision, K.F.; project administration, K.F. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All pictures represented and analysed in this paper were taken by Kurt Feyaerts, who further manages their being archived and disclosed to third parties upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alvarez, Juliana, Pierre-Majorique Léger, Marc Fredette, Shang-Lin Chen, Benjamin Maunier, and Sylvain Senecal. 2020. An Enriched Customer Journey Map: How to Construct and Visualize a Global Portrait of Both Lived and Perceived Users’ Experiences? Designs 4: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2020. Die Sprachlandschaft im Dispositiv der Pandemie. Aptum 16: 290–99. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, Marleen. 2018. Frankwatching. Zo Maak je de Ideale Buyer Persona. Available online: https://www.frankwatching.com/archive/2018/06/12/zo-maak-je-de-ideale-buyer-persona/ (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Balis, Janet. 2021. 10 Truths about Marketing After the Pandemic. Harvard Business Review, March 10, 10p. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, Michael, and Suzanne Kemmer. 2000. Usage-Based Models of Language. Stanford: CSLI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Claudine. 2015. Chief Marketer. Why Buyer Personas are the Core of Content Marketing. Available online: https://www.chiefmarketer.com/buyer-personas-core-content-marketing/ (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Brône, Geert. 2010. Bedeutungskonstitution in Verbalem Humor: Ein Kognitivlinguistischer und Diskurssemantischer Ansatz. Frankfurt: Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Chemko, Jannelle. 2016. Unami Marketing. You Know about Buyer Personas… But What about Seller Personas? Available online: https://umamimarketing.com/blog/you-know-about-buyer-personas-but-what-about-seller-personas/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Clapp, Rob. 2020. Global advertising spend to fall by 8.1% in 2020. WARC. Available online: https://www.warc.com/content/paywall/article/global-advertising-spend-to-fall-by-81-in-2020/132699 (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Clark, Herbert H. 1996. Using Language. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, Neil. 2020. Who Understands Comics? Questioning the Universality of Visual Language Comprehension. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Dancygier, Barbara, and Lieven Vandelanotte. 2017. Viewpoint phenomena in multimodal communication. Cognitive Linguistics 28: 371–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancygier, Barbara, Danielle Lee, Adrian Lou, and Kevin Wong. Forthcoming. Standing together by standing apart: Distance, safety, and fictive deixis in the COVID-19 storefront communication.

- Demsar, Vlad, Sean Sands, Colin Campbell, and Leyland Pitt. Forthcoming. Unprecedented, “extraordinary,” and “we’re all in this together”: Does advertising really need to be so tedious in challenging times? Business Horizons. in press.

- Diaz, A. 2020. See all the COVID-19 Cliche’s in One Big Fat Supercut. Advertising Age. Available online: https://adage.com/creativity/work/microsoft-sam-every-covid-19-commercial-exactly-same/2251551 (accessed on 18 February 2021).