Abstract

This paper investigates gender agreement mismatches between nominal expressions and the targets of agreement they control in two groups (adults and adolescents) of Heritage Greek speakers in the USA. On the basis of language production data elicited via a narration task, we show that USA Greek Heritage speakers, unlike monolingual controls, show mismatches in gender agreement. We will show that the mismatches observed differ with respect to the agreement target between groups, i.e., noun phrase internal agreement seems more affected in the adolescent group, while personal pronouns appear equally affected. We will argue that these patterns suggest retreat to default gender, namely neuter in Greek. Neuter emerges as default when no agreement pattern can be established. As adult speakers show less mismatches, we will explore the reasons why speakers improve across the life span.

1. Introduction

This paper investigates gender agreement mismatches between nouns and the targets of agreement they control in Heritage Greek. Following Rothman (2009, p. 156), “a language qualifies as a Heritage Language if it is a language that is spoken at home or otherwise readily available to young children, but, crucially, this language is not a dominant language of the larger (national) society.” The speakers that participated in our study qualify as such on the basis of this definition. It is widely acknowledged that the study of Heritage Speakers and their grammar provides a unique research field to further our understanding of the language faculty and to approach issues of language variation and change, see Benmamoun et al. (2013), Montrul (2016), Polinsky (2018), and Lohndal et al. (2019) for a recent overview.

In the spirit of this research, we compare two different age groups, adults and adolescents, of Heritage speakers (HSs) of Greek in the USA. As illustrated in (1), the variety of Greek spoken in the USA shows novel gender agreement patterns in comparison to Standard Modern Greek (SMG):

| 1 | a. | Adult Male US Bilingual speaker, informal written task | ||||

| Ke to skili | ide tin bala | ke | to | kiniguse | ||

| And the dog | saw 3SG the ball-FEM | and | it-NEUT | chase-IMP.PAST.3SG | ||

| ‘And the dog saw the ball and it was chasing it’. | ||||||

| a′. | SMG Ke to skili | ide tin bala | ke | tin | kiniguse | |

| And the dog | saw-3SG the ball-FEM | and | cl-FEM | chase-IMP.PAST.3S | ||

| ‘And the dog saw the ball and it was chasing it.’ | ||||||

| b. | Adolescent Female US Bilingual speaker, informal spoken task | |||||

| itan ena | mikri | ikogenia | ||||

| was a-NEUT | small-FEM | family-FEM | ||||

| ‘There was a small family.’ | ||||||

| b′. | SMG itan mia | mikri | ikogenia | |||

| was a-FEM | small-FEM | family-FEM | ||||

| ‘There was a small family.’ | ||||||

In (1a), the antecedent of the clitic bears feminine gender, but the clitic itself bears neuter. In (1b), the adjective closer to the noun agrees in gender with it, but the numeral exhibits neuter marking. In SMG, in both cases full formal agreement in gender is present within the DP, as shown in (1a′–b′). We will see that such mismatches are more pronounced within the adolescent group. We will compare these patterns to the gender agreement patterns produced by monolingual controls and to gender agreement mismatches that have been reported for other varieties of Greek in language contact situations.

In a recent comprehensive overview of the agreement patterns in heritage speakers’ production, Polinsky (2018, p. 206) reports that gender agreement shows effects of vulnerability in heritage speech independently of the gendered vs. un-gendered nature of the language these speakers are dominant in. It has been reported that gender undergoes ‘erosion’ in contact with English, a language that lacks gender, as in, e.g., American Norwegian (Lohndal and Westergaard 2016). Nevertheless, cases of erosion have been reported also for contact situations with a gendered language, e.g., Norwegian-dominant Russian speakers (Rodina and Westergaard 2013). Montrul et al. (2008, p. 515) state that “gender agreement appears to be a strong candidate for language loss in a language contact situation.” As further noted in Polinsky (2018), heritage speakers and L2 learners have great difficulties in computing gender agreement and this difficulty increases when the two constituents that enter agreement are separated, i.e., when they are non-adjacent.

The literature on gender in heritage grammars leads us thus to expect certain types of gender agreement mismatches in language contact situations involving Greek, a language that makes a three-gender distinction, especially under the influence of English, an un-gendered language. This has been discussed in the context of L2 Greek, e.g., Agathopoulou et al. (2010), and from the perspective of bilingual acquisition, see, e.g., Kaltsa et al. (2017). In this study, we will report on production data by Greek HSs and the gender agreement patterns that can be observed in these. Next to monolingual controls, we investigated two different age groups (adults vs. adolescents) of Heritage Greek speakers in the USA in two different levels of formality, formal and informal, and two distinct modes: oral and written. Our aim was to answer the following questions: what types of novel grammar patterns can be observed in the production of HSs of Greek? Do US Greek speakers behave differently from their monolingual counterparts? Do we find differences related to age, level of formality, or modality? To the extent that differences can be detected, are they due to cross-linguistic influence from English, an un-gendered language?

We were generally interested in novel, non-canonical, patterns in the production of Greek HSs and gender agreement mis-matches are one striking finding observed in our corpus. Our study adds to the previous literature empirically as it considers adolescent and adult speakers and also looks at a wider variety of agreement targets and asks the question to which extent the mismatches found conform to Corbett’s (2003, 2006) Agreement Hierarchy, thus testing the role of distance between agreement targets and the agreement controller in these mismatches.

As far as we are aware of, there is no other production study focusing on these issues and especially on Greek USA HSs. Kaltsa et al. (2017) were interested in the development aspects of gender in bilingual acquisition as well as on the role of cross-linguistic influence of a gendered language (German) vs. an un-gendered language (English). In Section 4.2, we will compare our results to theirs, although ours is a corpus study and theirs an elicited experimental one, by briefly also discussing preliminary results from Greek HSs in Germany. We will also compare our results to Seaman’s (1972) study, who interviewed Greek speakers in the area of Chicago in the 1970s, where some of our speakers are located, and to Paspali’s (2019) experimental study of adult HSs of Greek in Germany. We will also consider Karatsareas’s (2011) discussion of Asia Minor Greek dialects, which looks at gender re-analysis in these dialects from the perspective of the Agreement Hierarchy.

We will show that there is a difference between adult and adolescent speakers, meaning that the latter show quantitatively more patterns of gender agreement mismatches. We will further show that USA adolescents show more inconsistencies with respect to DP internal agreement, while DP external agreement is equally affected in both groups, surfacing with neuter gender. Specifically, with respect to DP external agreement both speaker groups resort to neuter gender, which, as we will see, is the default in Greek. The higher frequency of inconsistent patterns of DP internal agreement produced by the adolescent group suggest vulnerability with respect to concord and un-interpretable features, which will support our analysis of the overall patterns as the emergence of neuter gender as default, see, e.g., Tsimpli and Hulk (2013). We will also point out that declension class information seems to be relatively intact, albeit speakers may produce errors in case marking pointing to the independence of gender and declension class information in Greek. Our data do not reveal a difference with respect to the level of formality or modality. Since our adult speakers show mismatches but to a lesser degree, we will explore paths to understand why speakers improve across the life span. As our speakers do not belong to different generations, the factors that contribute to this change will be discussed at length.

The paper is structured as follows: in Section 2, we offer some information about our data collection. In Section 3, we offer some background about gender and declension classes in Greek and English. In addition, we present our assumptions concerning the structure of the DP (in Greek) and the gender agreement system of Greek and outline our predictions. In Section 4, we present our novel data, which we compare to other Greek contact varieties and previous literature on Greek. In Section 5, we offer our statistical analysis. In Section 6, we turn to a detailed discussion of our results. In Section 7, we conclude.

2. Materials and Methods

The USA Greek data discussed in this paper come from research carried out within the frame of the project AL 554/12-1 Nominal morpho-syntax and word in Heritage Greek across majority languages, part of the Research Unit 2537 Emerging grammars. The overall aim of this project was to build a corpus of Heritage Greek by collecting data from HSs of Greek in the USA and in Germany in different formal situations and to include monolingual controls in comparable age groups and situations. The current size and constitution of the corpus is as follows: The group of Greek HSs was recruited in New York City, NY and Chicago, IL in the USA and it consists of adults (N = 32, females: 18, mean age: 30.2, number of tokens: 10,629) and adolescents (N = 32, females: 16, mean age: 16.2, number of tokens: 10,327) Greek HSs. We have also collected data from monolingual controls, matched for age: 32 adults (females: 16, mean age: 27.4, number of tokens 14,954) and 32 adolescents (females: 16, mean age: 15.3, number of tokens 14,419). The monolingual controls have been raised by Greek parents in mainland Greece (Athens). They have not lived abroad for more than 6 months in a row. Their everyday and work language is predominantly Greek. We have also collected data from HSs of Greek in Germany: 27 adults (females: 17, mean age: 28.4, number of tokens 11,420) and 21 adolescents (female: 7, mean age: 16.5, number of tokens: 8200). Approximate total number of tokens of all sub-corpora: 69,589. The narration corpus is available online, see Supplementary Materials, https://zenodo.org/record/3236069#.XnoI1C1oTKI. While the USA and monolingual part of the corpus are complete, the collection of the German data is ongoing.

The detailed information on the participants in our corpus is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant information.

Table 2.

Information about our participants’ generation.

In the elicitation task, all participants after watching the video involving a car crash, had to narrate in Greek what happened both as a text message and as an audio message to a close friend in the informal register condition, and to the police via a written testimony and a message to the voice mail of the police station in the formal register condition.

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the German Linguistic Society (Project Identification Code: 2017-06-171120).

3. Background Assumptions

3.1. Background on Gender (Agreement) in Greek and in English

Corbett (1979, 1991) pointed out that in languages with grammatical gender systems, nouns can be divided into two groups for the purposes of gender agreement: so-called ordinary nouns can be assigned to a gender and any type of agreement target they control will show the same gender. On the other hand, so-called hybrid nouns behave differently, and their agreement specification varies depending on the depending on the target (Corbett 2006, p. 225). Corbett (2006) uses the terms syntactic vs. semantic agreement to refer to these patterns. Semantic agreement is agreement with the gender assigned to a noun by semantic rules, while syntactic/formal agreement is agreement with the gender assigned to a noun on the basis of formal rules.2 Corbett, furthermore, noted that cross-linguistically agreement targets may not all show the same patterns of agreement. Specifically, Corbett (2003, pp. 114–15), referring to examples involving more than one agreement target, states the following “there is a pattern in these and similar examples, and it concerns the target involved. The agreement specifications do not vary randomly with the targets. For instance, we find semantic agreement in the predicate, but not in attributive position. We never find the reverse situation, where semantic agreement would be required in attributive position but not in the predicate.” This led Corbett to propose the Agreement Hierarchy in 2 and to furthermore propose that possible agreement patterns are constrained as in 3, whereby the further target will show semantic agreement; (3) is syntactically defined by Corbett and is referred to as the Distance Principle (Corbett 2006, p. 235). The way to understand 2–3 is as follows: targets that appear outside of the controller noun phrase are the first to show semantic agreement, e.g., pronouns and clitics. Within the noun phrase, the adjectives closer to the noun agree formally, while those further away from the noun will show semantic agreement. We will come to a more specific structural implementation of this in Section 3.2:

| 2 | attributive > predicate > relative pronoun > personal pronoun |

| 3 | For any controller that permits alternative agreement forms, as we move rightwards along the Agreement Hierarchy, the likelihood of agreement with greater semantic justification will increase monotonically (that is, with no intervening decrease). |

Our understanding of the Hierarchy can be represented as in (4) below, following and extending Nübling’s (2015, p. 245) adaptation, and illustrating both DP internal and DP external targets:

| 4 | a. attributive > predicate > relative pronoun > personal pronoun |

| (article, adjective) adjective, verb | |

| formal/close agreement distant/semantic agreement | |

| b. Article > Adj 1 > Adj 2 > Adj 3 > Noun | |

| distant/semantic agreement formal/close agreement |

The Russian example in (5) illustrates how this hierarchy works: (5a) contains a hybrid noun, and the low adjective agrees in formal gender, while the high adjective agrees in semantic gender. As is shown in (5b), the reverse is not allowed, Pesetsky (2013, p. 17):

| 5 | a. | ?U menja očen’ | interesn-aja | nov-yj | vrač |

| by me very | interesting-F.NOM.SG. | new-M.NOM.SG. | doctor-NOM.SG. | ||

| b. | *U menja očen’ | interesn-yj | nov-aja | vrač | |

| by me very | interesting-M.NOM.SG. | new-F.NOM.SG. | doctor-NOM.SG. | ||

| ‘I have a very interesting new (female) doctor.’ | |||||

SMG has a three-gender system and all nouns in the language are classified into one of the three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. Ralli (2002) proposes that nouns are assigned gender on a basis of a mixture of morphological and semantic (sex) criteria. Specifically, animate nouns denoting male entities are masculine, while animate nouns denoting female entities are feminine, see (6).

| 6 | SMG | ||

| a. | o | pateras | |

| the-MASC | father-MASC | ||

| b. | i | mitera | |

| the-FEM | mother-FEM | ||

However, not all inanimate nouns are neuter; in fact, inanimate nouns are distributed to all three classes on the basis of formal criteria. Moreover, there are some animate nouns that are neuter, e.g., agori ‘boy’ and koritsi ‘girl’. The formal criteria can be roughly described as follows: inanimate nouns that end in -s are masculine, those in -a are feminine and those ending in -o or -i are neuter.

SMG has also a rather complex system of declension classes (DCs), 8 in total, according to Ralli (2000), but there is no one to one relationship between DCs and gender, see Table 3 from Alexiadou and Müller (2008), based on Ralli’s classification.

Table 3.

Standard Modern Greek (SMG) Declension Classes.

There are several nouns, the so-called profession nouns, that are unspecified for gender. These nouns nearly all belong to the same DC, namely Ralli’s DC 1, and there are some in DC 2. These nouns receive a gender specification via agreement with their referent, see Alexiadou (2004, 2017).3

| 7 | SMG | ||

| a. | o/i | jatr-os | |

| the-MASC/the-FEM | doctor-DC1 | ||

| b. | o/i | epihirimatia-s | |

| the-MASC/the-FEM | businessman-DC2 |

In SMG, nouns control agreement on the following set of agreement targets (Karatsareas 2011, p. 139): adjectives, definite and indefinite articles, demonstratives, a small number or cardinal numerals (‘one’, ‘three’ and ‘four’), all attributive numerals (ordinal, multiplicative, proportional), participles and pronouns. Formal agreement is required between the noun and stacked adjectives within the DP but also elements DP externally, e.g., predicative adjectives and clitics. Moreover, as there is no one to one mapping between DCs and gender the only way to actually view and test gender assignment in the language is via the use of the determiner, see also Kaltsa et al. (2017):

| 8 | SMG | |||||

| a. | i | megali | bala | |||

| the-FEM | big-FEM | ball-FEM | ||||

| ‘the big ball’ | ||||||

| b. | i | bala | ine | megali | ||

| the-FEM | ball-FEM | is | big-FEM | |||

| ‘The ball is big.’ | ||||||

| c. | tin | ida | ti | megali | bala | |

| cl-FEM | saw-1SG | the-FEM | big-FEM | ball-FEM | ||

| ‘I saw it, the big ball.’ | ||||||

Third person object clitic pronouns are identical to the definite determiners and bear gender, case and number information, apart from the fact that clitics lack a nominative from, see Table 4. Demonstratives and relative pronouns follow the pattern of nominal DC1masc, DC3fem and DC5neut:

Table 4.

SMG definite articles and clitic pronouns.

Typically, gender agreement is formal agreement (Chila-Markopoulou 2003; Holton et al. 1997, p. 498; Karatsareas 2011). In the case of nouns that exhibit a mismatch between their semantic and syntactic gender, Chila-Markopoulou (2003, pp. 148–49) notes that pronouns agreeing with koritsi ‘girl’ may appear in the feminine gender, and thus exhibit semantic agreement, as shown in (9) from Spathas (2010, p. 222). Karatsareas (2011) observes that this noun is the only exception in a system that is guided by a strictly formal agreement mechanism:4

| 9 | SMG | |||||

| a. | To | koritsi | ine | omorfo/ | *omorfi | |

| the-NEUT | girl-NEUT | is | pretty-NEUT/ | pretty-FEM | ||

| ‘The girl is pretty.’ SMG | ||||||

| b. | Pira | tilefono | to | koritsi | ||

| took-1SG | telephone-ACC | the-NEUT | girl-NEUT | |||

| ke tu/ tis | zitisa | na | vjume | |||

| and it/ her | asked-1SG | subj | go-out-1PL | |||

| ‘I called the girl and asked her out.’ | ||||||

However, gender unspecified nouns which receive gender specification from their referent show semantic agreement and not formal agreement, (see 10). In this case, SMG is different from Russian,5 which allows for syntactic agreement between ‘low’ adjectives and the noun, as we saw in (5):

| 10 | SMG | ||

| i Maria | ine kali/ | *kalos | |

| the Mary | is good-FEM/ | good-MASC | |

| ‘Mary is a good doctor.’ | |||

Several authors have proposed that neuter is the default gender in SMG. Specifically, Tsimpli and Hulk argue that since neuter is the value that is chosen when no agreement relation can be established, neuter serves as default in SMG. In support of this, consider (11) from Tsimpli and Hulk (2013, p. 133): in (11), the definite neuter determiner is used to nominalize clauses (Roussou 1991). In this case, the complement of the determiner does not bear any gender features, and neuter appears as the default on the determiner.

| 11 | SMG | |||||||

| To / | *o / | *i | oti | paretithike | simeni | oti | kurastike | |

| the-NEUTER/ | *the-MASC/ | *the-FEM | that | resigned-3SG | mean-3SG | that | got-tired-3SG | |

| ‘That he resigned means that he got tired.’ | ||||||||

As Tsimpli and Hulk further point out, neuter pronominal clitics are used resumptively in cases of clause-dislocation or doubling as in (12), concluding that “both D and pronouns show the use of default neuter when local (in DP) and non-local (CLLD) gender agreement cannot be established”, Tsimpli and Hulk (2013, p. 134).

| 12 | SMG | |||

| To thimame | (to) oti tha | erthis | noris | |

| It-remember-1SG | the that will | come-2SG | early | |

| ‘I remember it, that you will come early.’ | ||||

The neuter as default view receives support from acquisition studies, Mastropavlou and Tsimpli (2011), Tsimpli and Hulk (2013), as neuter is the preferred gender by young monolinguals (Mastropavlou 2006) and L2 learners of Greek. As has been shown in the literature, different groups of learners overgeneralize to neuter (Varlokosta 1995; Tsimpli 2003; Konta 2013). Studies on gender development report early target-like acquisition after a period of neuterization. For instance, Stephany (1997) reports that gender is acquired early on by the age of 2;3; Mastropavlou (2006) states that a target-like gender system is achieved at the age of 3;6, see also Marinis (2003), Stephany and Christofidou (2008).

As just mentioned, neuter emerges as default when no agreement can be established. There is a second type of gender default discussed in the work of Kazana (2011), Anagnostopoulou (2017) and Markopoulos (2018) that leads to a refinement of the view presented in Tsimpli and Hulk (2013). Specifically, there is a second type of default, which is actually the unmarked gender that emerges in, e.g., coordinated noun phrases containing both animates and inanimates. Coordinated noun phrases show a resolving form of gender agreement: in Greek, the target surfaces with masculine morphology, when the controller is human, (13), and with neuter morphology when the controller is inanimate, (14), and see Kramer (2015) for a cross-linguistic survey:

| 13 | SMG | |||||

| a. | O andras | ke | i gineka | ine | eksipni | |

| The man-MASC.SG | and | the woman-FEM.SG | are | intelligent-MASC.PL | ||

| ‘The man and the woman are intelligent.’ | ||||||

| b. | I gineka | ke | to pedi | ine | eksipni | |

| The woman-FEM.SG | and | the child-NEUT.SG | are | intelligent-MASC.PL | ||

| ‘The woman and the child are intelligent.’ | ||||||

| 14 | SMG | |||||

| a. | O pinakas | ke | i karekla | ine | vromika | |

| The blackboard-MASC.SG | and | the chair-FEM.SG | are | dirty-NEUT.PL | ||

| ‘The blackboard and the chair are dirty.’ | ||||||

| b. | I platia | ke | to pezodromio | ine | vromika | |

| The square-FEM.SG | and | the pavement-NEUT.SG | are | dirty-NEUT.PL | ||

| ‘The square and the pavement are dirty.’ | ||||||

With animals, both types of agreement are possible, see (15).

| 15 | SMG | |||||

| O skilos | ke | i gata | ine | agrii/ | agria | |

| The dog-MASC.SG | and | the cat-FEM.SG | are | wild-MASC.PL/ | NEUT.PL | |

| ‘The dog and the cat are wild.’ | ||||||

The refined and revised picture on gender values in SMG suggests that the language has two types of defaults, as Adamson and Šereikaitė (2019) propose for Lithuanian: (a) gender-default forms which are the unmarked gender forms. As Anagnostopoulou (2017) and Markopoulos (2018) argue, these forms are relativized to human-ness in Greek. Specifically, neuter is the default value for [-human] nouns, while masculine is the default value for [+human] nouns. (b) Neuter is the default value that emerges when no agreement can be established, i.e., it is the non-agreement default, as proposed in Tsimpli and Hulk (2013), see (11) above.

The inflectional patterns of adjectives are similar to those of nouns in Greek. Stephany (1997) observed that gender agreement between the determiner and the noun occurs early (around age 1;10), while agreement between the adjective and the noun is exhibited later, around age 2;4. Importantly, DP internal agreement is target-like although the occasional gender error with attributive adjectives is observed. Mastropavlou (2006) also noted a contrast between DP internal and DP external agreement: while DP internal agreement is target-like, external agreement is vulnerable especially for younger children.

As is well known, English has three genders, but only in the pronominal system, and gender agreement is purely semantic: in the case of animate targets, pronouns agree with their antecedents. Specifically, as stated in Siemund (2008) the agreement pattern in English follows the individuation hierarchy, Silverstein (1976), (Audring 2009, p. 127):

| 16 | human > animal > object > specific mass > unbounded abstract/unspecific mass |

| boy horse book my tea love/snow |

3.2. Background on the Structure of the (Greek) Noun Phrase and the Modeling of Gender Agreement

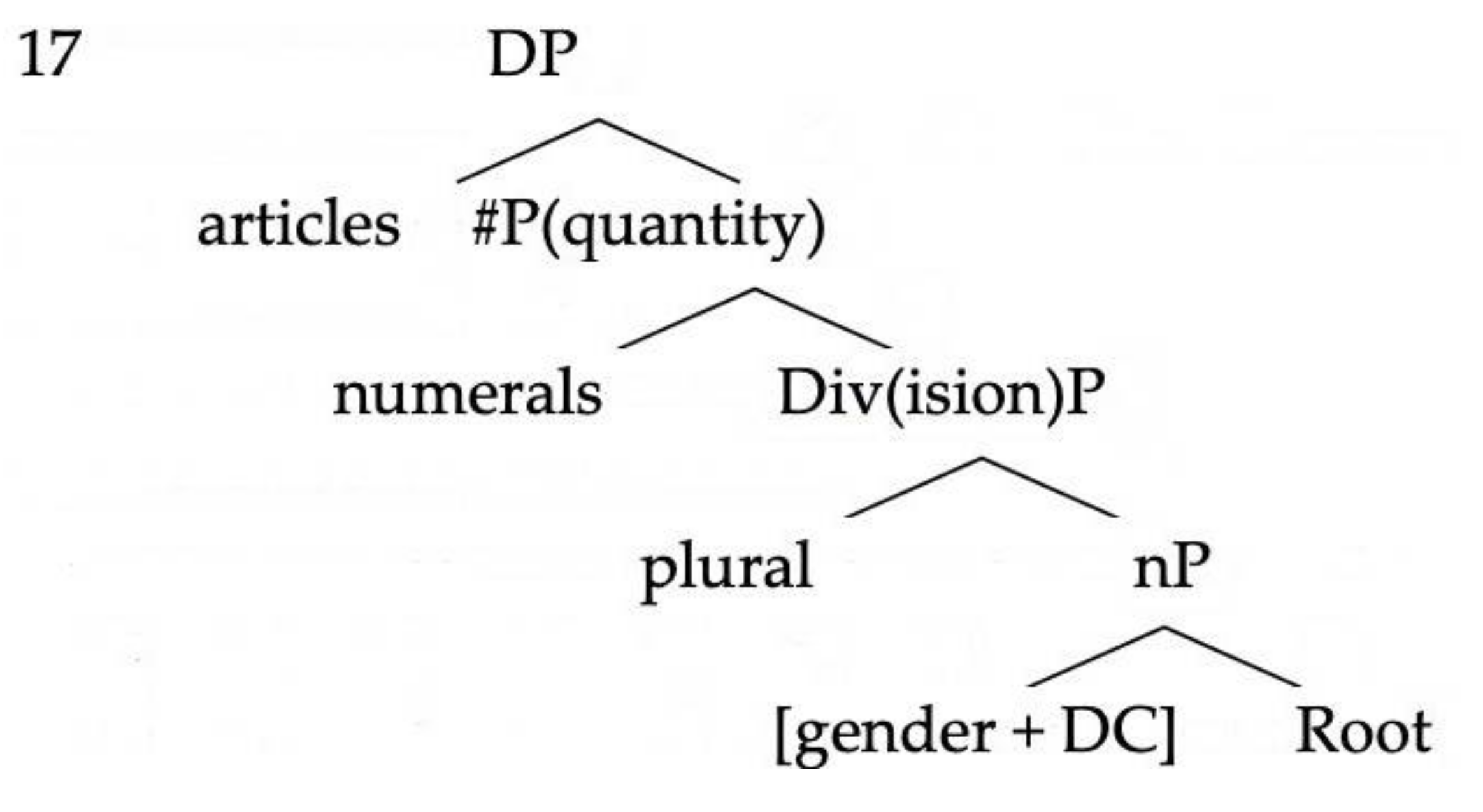

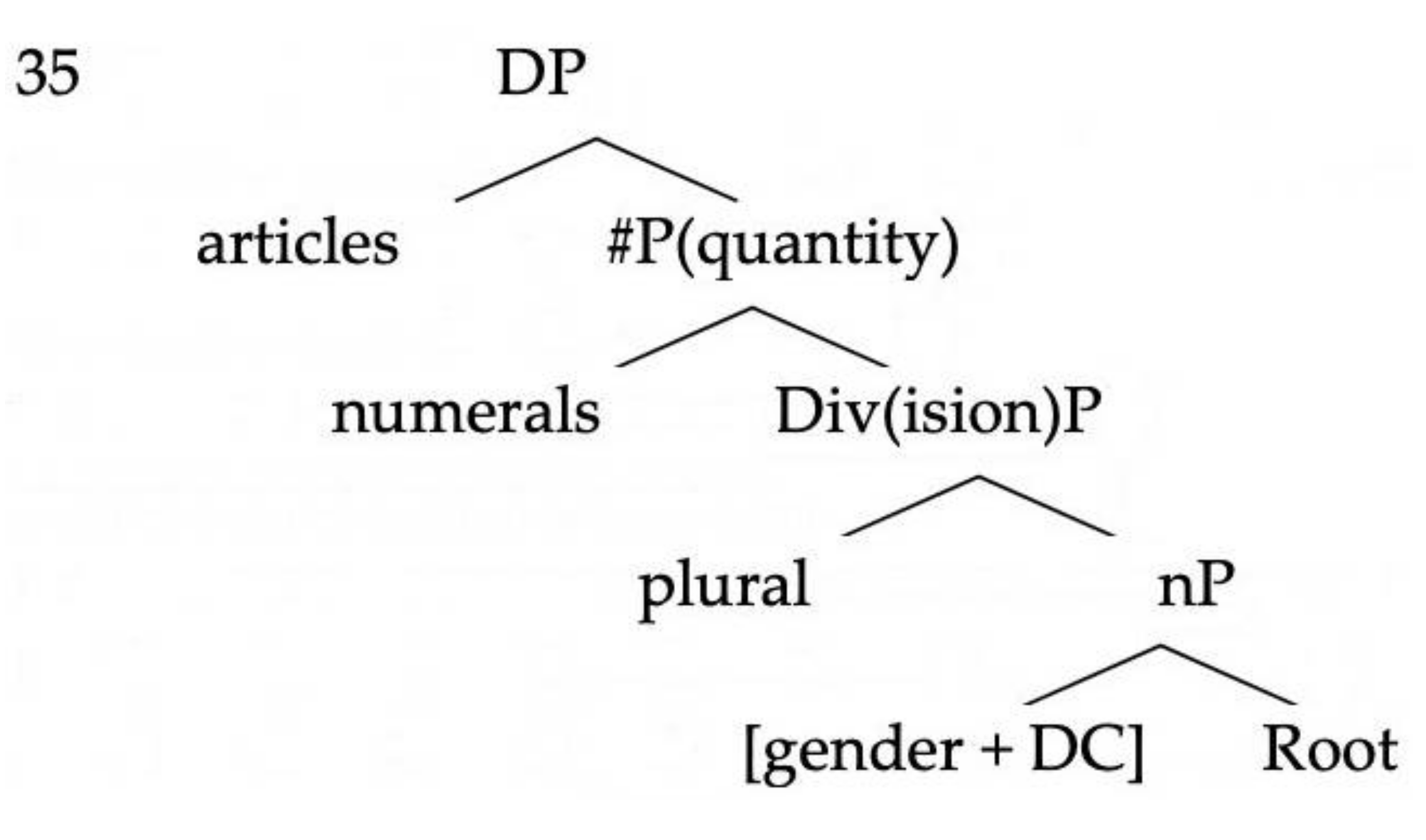

Our theoretical assumptions are couched within the framework of Distributed Morphology. Distributed Morphology is a theoretical framework that is characterized by two main features, summarized in Bobaljik (2017): (i) the internal hierarchical structure of words is syntactic, i.e., complex words are derived in the syntax, and (ii) syntax operates on abstract morphemes and the realization (exponence) of these morphemes takes place after syntax. Syntactic word formation manipulates acategorial roots that receive categorial specification in combination with so-called categorial heads, such as n and v, see Embick (2010). Recent work on gender in general and on Greek in particular has adopted this view, see, e.g., Kramer (2015), Alexiadou (2017), and Markopoulos (2018). Adopting these insights and the hierarchical nominal structure put forth in Borer (2005), we assume the nominal structure in (17):

In this structure, D hosts the definite article, #P introduces quantity readings and is responsible for the emergence of ‘individual’ interpretations, DivP is the locus of plurality and divides undivided mass, while nP is the locus of gender and DC features. Following Ralli (2000) and Alexiadou (2004), we assume that gender is a feature of nouns, specifically n + root combinations in (17). The same holds for DC. As in SMG all nominal morphology appears on n, i.e., there is no separate realization of gender, number and case features, we attribute this to Div-n fusion that leads to insertion of the one exponent (vocabulary item) realizing all these features, Alexiadou and Stavrou (1997):

| 18 | [Div PL [n DC]] -> [Div- n] Fusion |

Fusion is a process in Distributed Morphology that “takes two terminal nodes that are sisters and fuses them into a single terminal node. Only one Vocabulary item may now be inserted, an item that must have a subset of the morphosyntactic features of the fused node, including the features from both input terminal nodes.”, Halle and Marantz (1993, p. 116). To illustrate this, consider how Greek differs from Spanish. While in Spanish plural morphology is distinct from DC information leading to the insertion of two exponents for the two features as in muchach-o-s = boy-DC-PL ‘boys’, in Greek, there is no such separation. Thus, the plural form of, e.g., books contains one element, namely -a realizing all nominal features, as in vivli-a ‘books’.

With respect to gender in particular, we make the following assumptions: We assume the feature distribution of SMG gender in (19), see Anagnostopoulou (2017), and more specifically Markopoulos (2018). As Markopoulos argues in detail, the [±human] dimension corresponds to Kramer’s (2015), interpretable (i) gender features, while the [±feminine] dimension to her non-interpretable (u) gender on n, see Pesetsky and Torrego (2007). In this system, “underspecified features [+human] and [–human] are assigned by default to masculine and neuter respectively”, Markopoulos (2018, p. 52):6

| 19 | [+human, +feminine] → feminine |

| [+human, −feminine] → masculine | |

| [+human] → masculine | |

| [−human] → neuter | |

| [+feminine] → feminine | |

| [−feminine] → masculine |

With respect to gender agreement DP-internally, we assume that determiners and adjectives have uninterpretable and unvalued gender which are valued via Agree with the nominal head, as proposed by, e.g., Carstens (2000), and Tsimpli and Hulk (2013), Anagnostopoulou (2017) for Greek, cf. Norris (2014). From this perspective, DP-internal agreement (nominal concord) is treated as further type of agreement captured under the feature sharing system put forth in Pesetsky and Torrego (2007).7 In the case of hybrid nouns, n lack gender features. We hold that Greek hybrid nouns receive gender values from their referent, thus they do not carry any gender information, Alexiadou (2004). In fact, as also shown for Russian in Steriopolo (2018), the default gender for Greek hybrid nouns is masculine, which follows from Markopoulos’s (2018) feature system. For such nouns, we assume that gender specification takes place in D (Alexiadou 2004). Following the implementation in Kučerova (2018), and see also Steriopolo (2018), as the gender feature on D and the gender feature on n are part of the same Agree chain, D and n cannot undergo gender feature valuation independently of each other. Valuation via D is possible only if the gender feature on n has not been valued. In the case of hybrid nouns, the gender features on D are valued from the context and then those on n are valued as being part of the same link. This analysis holds, as it is generally the case, that there is one Agree chain, which includes both D and n. This ensures syntactic agreement for all DP internal elements.

We mentioned that Greek is unlike Russian in that it lacks mixed DP internal agreement. As we did find mixed agreement patterns in our Heritage Greek data, we will outline our assumptions about this here. Landau (2016) discusses cases of mixed DP-internal agreement from a variety of typologically unrelated languages, which all conform to Corbett’s “Distance Principle” (Corbett 2006, p. 235), repeated below:

| 20 | For any controller that permits alternative agreement forms, as we move rightwards along the Agreement Hierarchy, the likelihood of agreement with greater semantic justification will increase monotonically (that is, with no intervening decrease). |

As already pointed out in Section 3.1, distance involves both DP internal and DP external (clitics) targets. DP internally what we find cross-linguistically is pattern in (21a), from Landau (2016, p. 1018): the adjectives closer to the noun show syntactic agreement, while the ones further away show semantic agreement, see (5) above. This is a universal pattern and (21b) has, according to Landau, zero frequency.

| 21 | Mixed adjectival agreement |

| a. [Adj[Agr-Sem] [Adj[Agr-Syn] [N]]] | |

| b. *[Adj[Agr-Syn] [Adj[Agr-Sem] [N]]] |

To account for this, Landau proposes that the DP is divided into three zones, cf. Steriopolo (2018): Zone A shows syntactic agreement; Zone B may contain semantic agreement. Finally, zone C is where external agreement takes place it is the exclusive “contact point” between external probes (like v and T) and any nominal φ-feature. In Landau’s model, the head that is crucial in splitting the DP internal domain in zones is Number. Once this head is introduced, it functions as an intervener, and elements above this head are not able to value their phi-features with N. Thus, if an adjective attaches above Number it is not able to access the features of the noun and, thus, shows only semantic agreement. As an illustration, consider mixed gender agreement patterns in Russian, (5) repeated below. According to Landau, the higher adjective accesses semantic agreement, while the lower adjective has access to purely formal agreement, cf. Steriopolo (2018). This asymmetry is, according to Landau, made possible by the intervening number and, importantly, it is absolute:

| 5 | a. | ?U menja očen’ | interesn-aja | nov-yj | vrač |

| by me very | interesting-F.NOM.SG. | new-M.NOM.SG. | doctor-NOM.SG. | ||

| b. | *U menja očen’ | interesn-yj | nov-aja | vrač | |

| by me very | interesting-M.NOM.SG. | new-F.NOM.SG. | doctor-NOM.SG. | ||

| ‘I have a very interesting new (female) doctor.’ | |||||

In this case, the higher adjective, the one that is above number, will not be able to access the formal features of the nominal head. According to Landau, mixed patterns of agreement emerge if semantic, gender features are not specified on n. From this perspective, an important ingredient in the parametrization of agreement is the location of gender features, D or n. In Greek, the absence of gender features on n can lead to two default strategies, either the emergence of neuter, if no agreement can be established, or the emergence of masculine for human referents. In the former case, as in Tsimpli and Hulk (2013), as no agreement can be established a default realization will kick in. In other words, default values emerge when the computation proceeds as if the element with u features were not there, following (Bošković 2009, p. 472). In view of our discussion here, we expect this value to be neuter in Greek.

Landau also discusses cases in which the gender agreement mismatches involve external targets, e.g., the verb or in our case pronominal clitics, which we adopt here. Following Danon (2011), Landau (2016, pp. 996–97) assumes that D is the only head accessible for agreement from outside. Since in his system, D mediates only semantic agreement, Corbett’s hierarchy, repeated in 4a below, predicts that clitics will show semantic agreement as they are further removed from the agreement target:

| 4 | a. attributive > predicate > relative pronoun > personal pronoun |

| (article, adjective) adjective, verb | |

| formal/close agreement distant/semantic agreement |

This covers the cases of pronoun-antecedent agreement involving a controller noun phrase in one clause and the target of agreement, i.e., the clitic, in a subsequent clause. In our data we also find mismatches in clitic-doubling constructions, where the clitic and the full noun phrase are within the same clause. The treatment of clitic-doubling is controversial, see Anagnostopoulou (2006) for a comprehensive overview. Anagnostopoulou (2003) analyzes clitics in Greek clitic-doubling constructions as instances of the formal features of their associate DPs. Others view clitic-doubling as syntactic agreement, see, e.g., Preminger (2019). Anagnostopoulou’s (2003) analysis did not distinguish between formal and semantic features on DPs. In principle, one could assume that clitics enter both formal and semantic agreement with their associate DPs. If clitic-doubling is indeed an instance of agreement, and clitics move away from their associate DPs as is standardly assumed in the literature, we expect this agreement relationship to be affected by (4a).8

3.3. Research Questions and Predictions

Our aim in this study is to answer the following questions: do we find agreement mismatches in the production of Heritage speakers of Greek? If we do find such mismatches, do they conform to Corbett’s (2003, 2006) Agreement Hierarchy, (2–4), and Landau’s (2016) modeling of this hierarchy? Do USA Greek speakers behave differently from their monolingual counterparts? Do we find differences related to age, level of formality, or modality? To the extent that differences can be detected, are they due to cross-linguistic influence from English, an un-gendered language? We mentioned in our overview on gender that in Greek this is a phenomenon that is early acquired. Thus, to the extent that we find age differences the question is what these can be attributed to: if for instance adult speakers show more mismatches than younger speakers, attrition might be an explanation. If this is not the case, a different account must be established.

In Section 3.1, we pointed out that common to both English and Greek are agreement targets involving pronouns. For this reason, we focused on this distribution. If the structure of the English system plays a role in determining the system in heritage Greek, then we expect to see effects of gender re-analysis, since the English system is based on purely semantic [+human] features for controlling agreement. Moreover, we expect lack of agreement on attributive modifiers, as English lacks such agreement targets. With respect to articles, we expect that English Greek speakers may show agreement mismatches, see also Kaltsa et al. (2017).9

Moreover, if Corbett’s distance principle and Landau’s universal structure in (21a) are truly universal, then we might expect heritage grammars to also conform to them in that, see also Laleko (2018) and Fuchs (2019) on Heritage Russian and Heritage Polish, respectively: (a) if agreement mismatches occur these are to be found with clitics and pronouns, as they are distant targets; (b) to the extent that mixed agreement patterns are found DP internally, we expect low adjectives to formally agree with their target, while higher adjectives may only show semantic agreement, as they are distant from the target. These predictions are also formulated on the basis of two other studies that have discussed gender re-analysis in language contact situations, namely Dolberg (2019) on Old English–Old Norse contact, and Karatsareas (2011) on Greek–Turkish language contact, cf. Gillon and Rosen (2018) for Michif. These authors point out that the re-analysis of the gender system in English and Greek respectively proceeds as follows: more distant targets show semantic agreement first. In other words, if we observe changes in the English Greek data, again we expect them to affect distant controllers, i.e., clitics and higher adjectives/determiners.

Since gender is an early acquired phenomenon in Greek, as shown by Stephany (1997), Marinis (2003), Mastropavlou (2006), Stephany and Christofidou (2008) and our younger speakers are adolescents, a priori attrition cannot be excluded; should we, however, find differences between the two age groups, this will inform our analysis in terms of incomplete acquisition vs. attrition, as there is no generation gap between our participants, see Table 2. We will deal with this extensively in Section 6. Finally, since gender is a core grammatical phenomenon, and our nouns belong to the everyday vocabulary, we do not expect to find differences with respect to level of formality and mode of communication.

4. Results

4.1. Gender Agreement Mismatches in Heritage Greek in Our Corpus

Below, (22) illustrates some examples of mismatches involving clitics from US Greek, where the target is underlined10. While in (22a–d), the clitic and its antecedent are in different clauses, (22i) involves a possessor clitic, and (22e–h) are instances of clitic doubling:

| 22 | a. | Adult Female US bilingual speaker, informal written task | |||||||||

| i | bala | tu | ksafniase | ena skilo | ke | pige | ja na | to | piasi | ||

| the | ball-FEM | his | surprised-3SG | a dog | and | went-3SG | so that | it | catch-3SG | ||

| ‘His ball surprised a dog who ran to catch it.’ | |||||||||||

| b. | Adolescent Male US bilingual speaker, formal spoken task | ||||||||||

| tu | efige | i | bala | ena skili | apendi | to | ide | ||||

| him | left-3SG | the | ball-FEM | a dog | across | it | saw-3SG | ||||

| ‘He dropped the ball and a dog across the street saw it.’ | |||||||||||

| c. | Adult Male US bilingual speaker, formal written task | ||||||||||

| O andras | ehase | ti | bala | ke to skili | petahtike | na | to pari | ||||

| the man | lost-3SG | the | ball-FEM | and the dog | ran-3SG | SUBJ | it take-3SG | ||||

| ‘The man lost the ball and the dog ran to catch it.’ | |||||||||||

| d. | Adult Female US bilingual speaker, informal spoken task | ||||||||||

| ide | to | skilaki… | ke | stamatise | ke | de | ton | htipise | |||

| saw-3SG | the | dog-DIM | and | stopped-3SG | and | NEG | him | hit-3SG | |||

| ‘He saw the dog and stopped in order not to hit it.’ | |||||||||||

| e. | Adolescent Male US bilingual speaker, formal spoken task | ||||||||||

| to | skilaki | pidikse | na | to | pari | ti | bala | ||||

| the | dog-DIM | jumped-3SG | SUBJ | ti | take-3SG | the | ball-FEM | ||||

| ‘The dog jumped to catch the ball.’ | |||||||||||

| f. | Adolescent Female US bilingual speaker, informal spoken task | ||||||||||

| pige | na | to | akoluthisi | ti | bala | ||||||

| went-3SG | SUBJ | it | follow-3SG | the | ball-FEM | ||||||

| ‘It went to follow the ball.’ | |||||||||||

| g. | Adolescent Female US bilingual speaker, informal spoken task | ||||||||||

| ke | tora | tha | to | parun | tin | astinomia | |||||

| and | now | FUT | it | call-3PL | the | police-FEM | |||||

| ‘and now they will call the police.’ | |||||||||||

| h. | Adult Male US bilingual speaker, formal spoken task | ||||||||||

| pige | na | to | pari | ti | bala | ||||||

| went-3SG | SUBJ | it | take-3SG | the | ball-FEM | ||||||

| ‘He went to catch the ball.’ | |||||||||||

| i | Adolescent Male US bilingual speaker, formal spoken task | ||||||||||

| i. | gineka | epese | ta | pragmata | tu | ||||||

| the | woman | fell-3SG | the | things | his-MASC?/NEUT? | ||||||

| ‘The woman dropped her stuff.’ | |||||||||||

Example (22d) is illustrative of the mixed status animals have in Greek, where actually both a masculine and a neuter form of the word corresponding to dog is possible o skilos vs. to skili, respectively. The pronoun referring back to the NP bears neuter. In several of our examples the mis-match is found also in clitic-doubling structures (e–h).

In (23), we illustrate DP internal mismatches:

| 23 | a. | Adolescent Female US bilingual speaker, informal spoken task | ||||||

| ke | ena | ali | gineka pu itan apendi sto aftokinito tis | |||||

| and | one-NEUT | another-FEM | woman that was across in car hers | |||||

| ‘and another woman who was across the street in her car…’ | ||||||||

| b. | Adolescent Female US bilingual speaker, informal spoken task | |||||||

| itan | ena | mikri | ikogenia | |||||

| was | a-NEUT | small-FEM | family-FEM | |||||

| ‘There was a small family.’ | ||||||||

| c. | Adolescent Male US bilingual speaker, formal spoken task | |||||||

| apo | to | ali | meria | tu | dromu | |||

| from | the-NEUT | other-FEM | side-FEM | the | street-GEN | |||

| ‘from the other side of the street’ | ||||||||

| d. | Adolescent Male US bilingual speaker, formal written task | |||||||

| ke | afton | to | aftokinito | stamate | ||||

| and | this-MASC | the | car-NEUT | stopped-3SG | ||||

| ‘and the car stopped.’ | ||||||||

| e. | Adolescent Female US bilingual speaker, informal written task | |||||||

| na | htipisi | mia | aspro | aftokinito | ||||

| subj | hit-3SG | one-FEM | white-NEUT | car-NEUT | ||||

| ‘to hit a white car.’ | ||||||||

| f. | Adolescent Male US bilingual speaker, formal written task | |||||||

| ehi | mia | allo | gineka | me | a | skeli | ||

| has | one-FEM | other-NEUT | woman | with | a | dog | ||

| ‘There was one other woman with a dog.’ | ||||||||

In the above examples, DC information on nouns is preserved. As we wanted to see which parts of Corbett’s hierarchy are affected and to which degree, we present the mismatches in three different categories, DP internal agreement, clitic pronoun and pronoun agreement in, e.g., relative clauses. As is shown in Table 5 and Table 6, monolingual speakers basically show no mis-matches, while the picture is very different for the US HSs of Greek. We will discuss this in detail in Section 5 where we present the statistical analysis of our findings. Basically, USA HSs speakers of Greek show mismatches in the category of DP internal agreement and clitic agreement, and the adolescents seem to produce more such mis-matches:

Table 5.

Results. US Greek Heritage speakers (HSs), illustrating percentage of errors.

Table 6.

Results. Greek monolingual controls, illustrating percentage of errors.

4.2. A Comparison with Agreement Mismatches in Other Studies

Agreement mismatches of the type described in the previous section have been reported for other Greek contact varieties. Karatsareas (2011) discusses four such varieties, namely Cappadocian, Pharasiot, Pontic, and Rumeic that have been in contact with an ungendered language, namely Turkish. The overall pattern he found can be summarized as follows: “two major developments emerge from the description of the gender agreement patterns in Cappadocian, Pharasiot, Pontic and Rumeic: semantic agreement in Pontic and Rumeic, and neuter agreement in Cappadocian and Pharasiot. In the former case, inanimate and/or animal masculine and feminine nouns trigger agreement in the neuter on the various targets controlled by them. Targets controlled by human masculine or feminine nouns appear in their masculine and feminine forms. In the latter case, masculine and feminine nouns trigger agreement in the neuter on their targets, irrespective of their meaning. Both developments are clear innovations of the dialects compared to SMG syntactic agreement”, see Karatsareas (2011, pp. 160–61).

The four varieties differ from one another in that, in Cappadocian, the tripartite gender system has been lost. In this case, all nouns behave as if they were neuter. By contrast, Pharasiot preserves a three-gender system, which however is only visible in the case of the definite article. Pontic preserves a three-gender system. Finally, Rumeic gender assignment operates on the basis of semantic criteria: nouns denoting male human entities are masculine, those denoting female human entities are feminine, and all other nouns are neuter. The overall conclusion Karatsareas offers is that the development of semantic agreement is evidence that the semantic core of the Modern Greek gender assignment system plays a central role in gender assignment and agreement in these dialects.

Karatsareas (2011) then proposes that the picture we observe in these dialects cannot solely be the result of language contact with Turkish, a genderless language, as some instances of semantic agreement were present prior to the extensive contact with Turkish. The patterns observed follow a generalization of semantic agreement to all targets, beginning with the personal pronoun that happens in five stages, according to Karatsareas (2011). In stage 1, we have a three-gender system and a purely syntactic agreement, (24a), which is the system of SMG. We then find re-semanticization of gender in the sense that the basic distinction is animate vs. inanimate followed by restructuring, i.e., semantic agreement with targets far away from the controller. Re-semanticization involves the emergence of the gender default in the sense of unmarked gender relativized to animacy. In stage 2, personal pronouns show semantic agreement, while all other targets show syntactic agreement, (24b). In stage 3, semantic agreement extends rightward and pronouns as well as predicates show semantic agreement, (24c). In stage 4, all targets with the exception of determiners show semantic agreement, (24d), and finally in stage 5 all targets show semantic agreement (24e), from Karatsareas (2011, pp. 189–90):

| 24 | a. | I | aspri | i | porta | ine | klisti | ego | tin | eklisa. |

| the.FEM | white.FEM | the.FEM | door.FEM | is | closed.FEM | I | her | closed. | ||

| ‘The white door is closed. I closed it.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | I | aspri | i | porta | ine | klisti | ego | to | eklisa. | |

| the.FEM | white.FEM | the.FEM | door.FEM | is | closed.FEM | I | it | closed. | ||

| c. | I | aspri | i | porta | ine | klisto | ego | to | eklisa. | |

| the.FEM | white.FEM | the.FEM | door.FEM | is | closed.NEUT | I | it | closed. | ||

| d. | to | aspro | i | porta | ine | klisto | ego | to | eklisa. | |

| the.NEUT | white.NEUT | the.FEM | door.FEM | is | closed.NEUT | I | it | closed. | ||

| e. | to | aspro | to | porta | ine | klisto | ego | to | eklisa. | |

| the.NEUT | white.NEUT | the.NEUT | door.NEUT | is | closed.NEUT | I | it | closed. | ||

Karatsareas’s discussion showed that the reorganization of gender is better captured under a language internal explanation that has its beginning in the ancestor dialect of all these varieties, which predates the intensive language contact with Turkish. Importantly, his study provides us with the tools to distinguish between processes of re-semanticization, as retreat to an unmarked form, as opposed to emergence of neuter as default strategy, which is the result of the lack of agreement. We will discuss this in Section 6.

Turning to studies of HSs of Greek, the results from our USA HSs align with the errors reported in Seaman (1972), who identified a general neuterizing tendency in the speech of Greek-Americans.11 Seaman (1972, p. 156) observed several cases of gender mismatches, shown in (25–27), where we see that his speakers produced neuter determiners even with human referents:

| 25 | Masculine > neuter | |||||

| a. | apo | to | amo | (2nd generation) | ||

| from | the-NEUT | sand | ||||

| ‘from the sand’ | ||||||

| b. | ine | ena | anthropo | (2nd–3rd generation) | ||

| is | a-NEUT | man | ||||

| ‘there is a man’ | ||||||

| 26 | Feminine> Neuter | |||||

| a. | fuskes | ta | leme elinika | (2nd generation) | ||

| balloons-FEM | them-NEUT | call in Greek | ||||

| ‘We call them balloons in Greek.’ | ||||||

| b. | pedia | ki | ena | mama | (3rd generation) | |

| children | and | a-NEUT | mother | |||

| ‘children and a mother’ | ||||||

| 27 | edo ine | ena, | mia | gineka | (2nd–3rd generation) |

| here is | one-NEUT, | one-FEM | woman | ||

| ‘There is a woman here.’ | |||||

Seaman’s study just reports errors thus, we are not able to see what these speakers can actually produce correctly. Nevertheless, he states (Seaman 1972, p. 157) “that many of the first- and second-generation speakers retain the correct non-neuter Greek gender for many nouns”. However, Seaman does provide us a with a full list of differences between the generations of speakers he interviewed. Assuming that he is correct with respect to his observations about the 1st generation immigrants in his survey, we can conclude that his speakers do not show the effects of gender attrition. If these speakers provide the input to the 2nd and 3rd generation speakers of our study, we can speculate that these have been exposed to a rather intact gender system.

Kaltsa et al. (2017) deal with the acquisition of gender assignment and agreement with Greek–English and Greek–German bilinguals. In our study, we did not control for gender assignment. However, we do observe that several US Heritage speakers omit articles, a fact which we take to suggest that they have problems with gender assignment as well. Specifically, Kaltsa et al. (2017, p. 24) note: “in the gender agreement tasks, on the other hand, neuter and masculine are discriminated since the former shows significantly better scores compared to masculine and feminine shows the lowest performance. Note also that both bilingual groups performed similarly in the gender agreement tasks and were significantly more accurate with neuter than with masculine and feminine suggesting that neuter is treated as the default value, giving rise to fewer errors.”

Paspali (2019) tested gender agreement with adult HSs of Greek in Germany. In total, 52 participants (mean age 21.6) were presented with pictures and listened to the preselected questions constructed by the experimenter to elicit gender on adjectival predicates and pronominal reference. Her group of speakers performed at ceiling in both structures and was not statistically different from the monolingual controls. This is surprising, as, German, like Greek, has a three-gender system, but its system of gender agreement works rather differently: predicates are not marked for gender, and attributive adjectives carry gender marking only in the case of indefinite noun phrases. Pronouns are marked for gender. Unlike English, German shows formal agreement even with inanimates. However, German Mädchen ‘girl’ may show semantic agreement on pronominal targets, as was shown above for Greek, see Corbett (1991).

Although our data collection in Germany has not been completed yet, we do have a sub-corpus with data from German Heritage speakers of Greek, as outlined in Section 2. Example (28) illustrates some of these data. It is interesting to note that the mismatches in (28) occur with personal and relative pronouns; (28a) is again suggestive of the mixed status of gender on animals.

| 28 | a. | Adult Female German bilingual speaker, formal written task | |||||

| ihe | ena | skilo | mazi tis | afto | gagvise | ||

| had | a | dog-MASC | with her | this-NEUT | barked | ||

| ‘She had a dog with her. It barked.’ | |||||||

| b. | Adult Female German bilingual speaker, formal written task | ||||||

| ipirhe | mia | sigrusi… | to opio | egine | |||

| there was | a | collision-FEM | the which-NEUT | took place | |||

| ‘There was a collision which took place.’ | |||||||

Table 7 below shows the agreement mismatches found currently in our corpus.

Table 7.

Preliminary Results. German HSs (DE), illustration of percentage of errors.

At first sight, the above data suggest the gender agreement pattern DP internally is intact; to the extent that we find mismatches these seem to be with pronouns and clitics, although the adult group shows two errors in DP internal agreement. Moreover, we are led to conclude that cross-linguistic interference might not be the reason why the USA heritage group behaves differently: while German, like English, lacks DP internal gender agreement, our German speakers behave similarly to monolinguals. Interestingly, here the picture is the reverse with respect to DP internal agreement in the sense that the adults produce some errors, but the adolescents are error free. We leave this for future research.

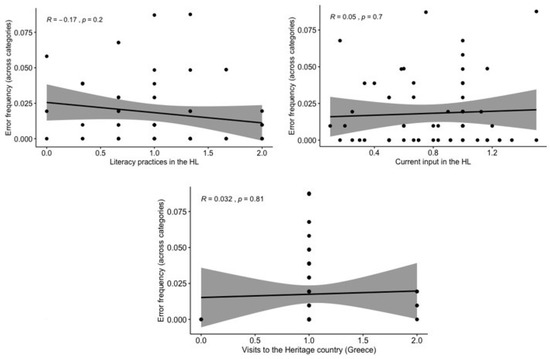

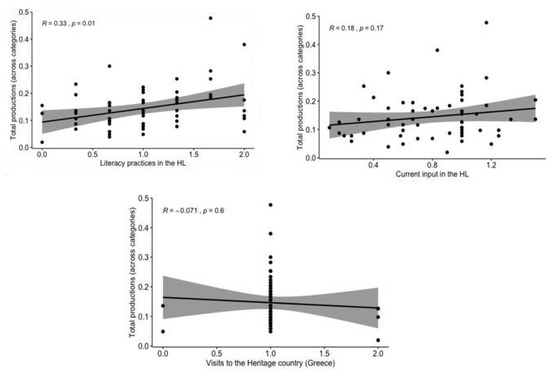

5. Statistical Analysis

In view of the fact that our sub-corpora, see Section 2, differ in the number of tokens they contain, we carried out a normalization process in order to be able to perform a statistical analysis. The normalization procedure was conducted before the analysis by calculating a per basis frequency, here the frequency per hundred (100) tokens for errors and total productions for each participant in each of the three agreement categories. The (normalized) frequencies (dependent variables) are per participant and agreement category. This leads to a bigger amount of available data and allows us to take into consideration the variability among speakers, which is not possible when analyzing frequency data averaged over groups.

The statistical analysis was conducted in R (R Core Team 2019) using the lme4 package to fit linear mixed models on normalized frequencies of errors and total productions. Regarding random effects, only subjects (Subject) were included in all models applied. Age Group with two levels (adult, adolescent), Agreement Category with three levels (Clitic, DP internal, Pronoun) and their interaction (2 × 3) were used as fixed effects.

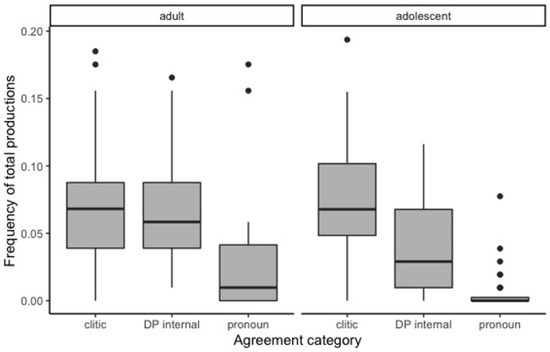

Total productions. Two different models were constructed: one with an interaction between the two predictors (Age Group, Agreement Category), and one without. A likelihood ratio test between these models revealed that the interaction between Age Group and Agreement Category reached significance (χ2(2) = 9.46; p = 0.009).

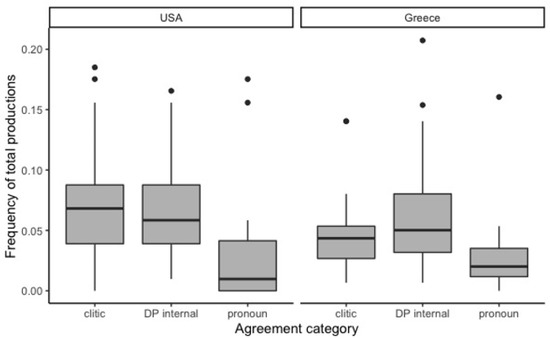

Within groups. Adults. The mixed-effects model detected a significant difference between Clitic and Pronoun, with the latter indicating a lower frequency of total productions (β = −0.04; SE = 0.01; t = −4.55; p < 0.0001). The difference between the DP internal and the Pronoun categories also reached significance, as instances in the latter were produced less frequently by adult HSs in the USA (β = −0.04; SE = 0.01; t = −4.36; p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference between the Clitic and the DP internal levels in this subgroup (β = −0.002; SE = 0.01; t = −0.19; p = 0.85) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Normalized frequency of total productions for each agreement category (clitic, DP internal, pronoun) per age group (adult, adolescent) within the USA group.

Adolescents. The model revealed a significant difference between the Clitic and the Pronoun (β = −0.07; SE = 0.01; t = −8.26; p < 0.0001), as well as between the Clitic and the DP internal conditions (β = −0.04; SE = 0.01; t = −4.48; p < 0.0001), with Clitic indicating the highest frequency of productions in both cases. The difference between the DP internal and the Pronoun categories was also proven significant, with total productions in the latter being less than those in the former category (β = −0.03; SE = 0.01; t = −3.78; p = 0.0003), (see Figure 1).

Between groups. The difference between adults and adolescents was revealed significant in the DP internal condition, with adolescents showing fewer total productions than adults in this category (β = −0.03; SE = 0.01; t = −2.94; p = 0.004). In the Pronoun condition, adolescents also produced significantly less instances than adults (β = −0.02; SE = 0.01; t = −2.18; p = 0.03). However, no significant difference between adults and adolescents was observed in the Clitic category (β = 0.007; SE = 0.01; t = 0.75; p = 0.46), (see Figure 1).

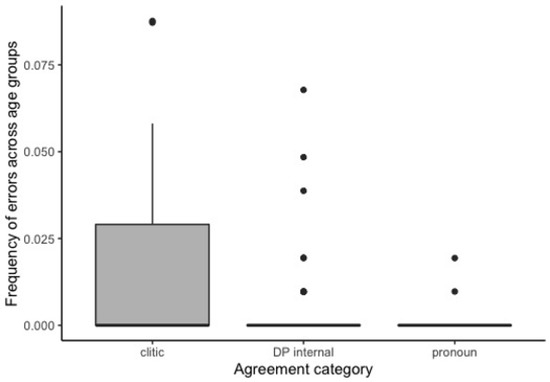

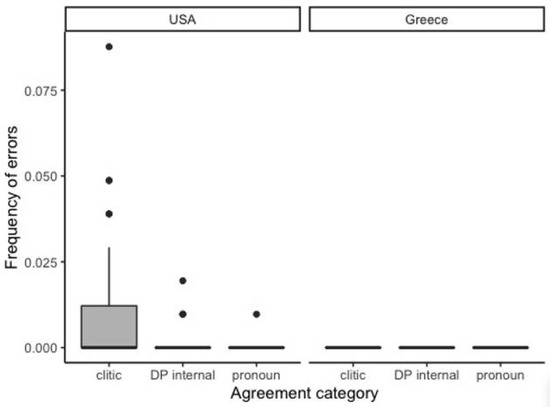

Errors Two different models were constructed: one with an interaction between the two predictors (Age Group, Agreement Category), and one without. A likelihood ratio test between these models revealed that the interaction between Age Group and Agreement Category did not reach significance (χ2(2) = 1.04; p = 0.59). Agreement Category was the only predictor with a significant effect in this analysis (F(2, 172) = 13.42; p < 0.0001).

Across groups. The mixed-effects model detected a significant difference between the Clitic and the DP internal conditions, with the latter showing less errors (β = −0.009; SE = 0.003; t = −3.59; p = 0.0004). The difference between Clitic and Pronoun, which indicated a much lower frequency of errors, also reached significance here (β = −0.013; SE = 0.003; t = −5.02; p < 0.0001), (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Normalized frequency of errors for each agreement category (clitic, DP internal, pronoun) across age groups (adult, adolescent) within the USA group.

We compared both age groups in the USA to their monolingual peers. Beginning with the adults, the same procedure was followed in the statistical analysis, but with different predictors, Country with two levels (USA, Greece), Agreement Category with three levels (Clitic, DP internal, Pronoun) and their interaction (2 × 3) were used as fixed effects.

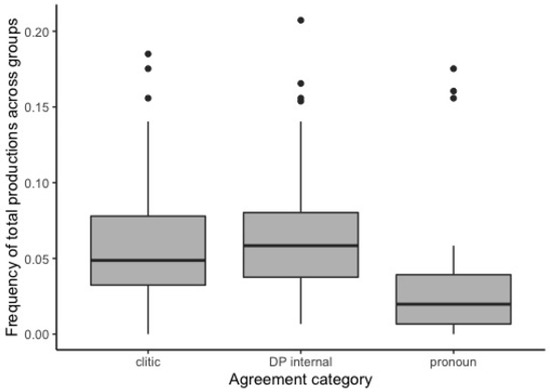

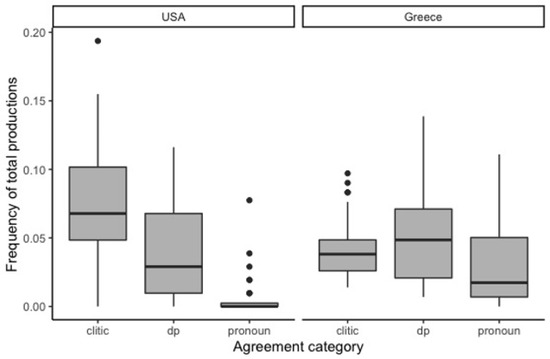

Total productions. Two different models were constructed: one with an interaction between the two predictors (Country, Agreement Category), and one without. A likelihood ratio test between these models revealed that the interaction between Country and Agreement Category did not reach significance (χ2(2) = 3.81; p = 0.15). Agreement Category was the only predictor with a significant effect in this analysis (F(2, 118) = 24.01; p < 0.0001).

Across groups. The model detected a significant difference between the Pronoun and the DP internal conditions, with more instances produced in the latter category (β = 0.04; SE = 0.01; t = 6.46; p < 0.0001). The difference between the Pronoun and the Clitic categories also reached significance, where the frequency of total productions in the latter was higher than in the former (β = 0.03; SE = 0.01; t = 5.40; p < 0.0001), (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Normalized frequency of total productions for each agreement category (clitic, DP internal, pronoun) across countries (USA, Greece) within the adults’ group.

Within groups. Greece. The model detected a significant difference between Clitic and Pronoun, with the latter indicating a lower number of total productions in this subgroup (β = −0.03; SE = 0.01; t = −5.40; p < 0.0001). The difference between the DP internal and the Pronoun categories also reached significance, as instances in the latter were produced less frequently than instances in the former category (β = −0.04; SE = 0.01; t = −6.46; p < 0.0001). The difference between DP internal and Clitic was not proven significant here (β = −0.01; SE = 0.01; t = 1.05; p = 0.29), (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Normalized frequency of total productions for each agreement category (clitic, DP internal, pronoun) per country (USA, Greece) within the adults’ group.

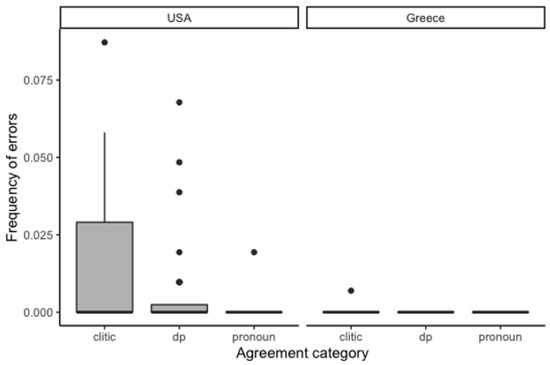

Errors: Two different models were constructed: one with an interaction between the two predictors (Country, Agreement Category), and one without. A likelihood ratio test between these models revealed that the interaction between Country and Agreement Category reached significance (χ2(2) = 18.74; p < 0.0001).

Within groups. Greece. No differences were detected between agreement categories, since error rates in this group were consistently at zero.

Between groups. The results of the mixed-effects model revealed a significant difference between adults in the USA and adults in Greece in the Clitic condition, with HSs in the USA showing more error instances than their monolingual peers (β = 0.01; SE = 0.002; t = 5.72; p < 0.0001). No significant differences were detected in the DP internal (β = 0.001; SE = 0.002; t = 0.62; p = 0.54) or the Pronoun category (β = 0.0003; SE = 0.002; t = 0.16; p = 0.88), (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Normalized frequency of errors for each agreement category (clitic, DP internal, pronoun) per country (USA, Greece) within the adults’ group.

USA vs. Monolingual group (adolescents)

Turning now to a comparison of the USA and monolingual adolescent group, the same fixed effects as in the adults’ analysis were used.

Total productions. Two different models were constructed: one with an interaction between the two predictors (Country, Agreement Category), and one without. A likelihood ratio test between these models revealed that the interaction between Country and Agreement Category reached significance (χ2(2) = 29.78; p < 0.0001).

Within groups. Greece. The mixed-effects model detected a marginally significant difference between the Clitic and the Pronoun conditions, with the latter indicating a lower number of total productions (β = −0.01; SE = 0.01; t = −1.87; p = 0.06). The difference between the DP internal and the Pronoun categories also reached significance, as instances in the latter were produced less frequently than instances in the former (β = −0.03; SE = 0.01; t = −3.17; p = 0.002), (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Normalized frequency of total productions for each agreement category (clitic, DP internal, pronoun) per country (USA, Greece) within the adolescents’ group.

Between groups. The difference between adolescents in the USA and adolescents in Greece was revealed significant in the Clitic category, with HSs in the USA producing more instances in this category than their monolinguals peers (β = 0.04; SE = 0.01; t = 4.36; p = 0.00002). In the Pronoun condition, adolescents in the USA produced significantly less instances than adolescents in Greece (β = −0.02; SE = 0.01; t = −2.77; p = 0.006), (see Figure 6).

Errors: Two different models were constructed: one with an interaction between the two predictors (Country, Agreement Category), and one without. A likelihood ratio test between these models revealed that the interaction between Country and Agreement Category reached significance (χ2(2) = 11.86; p = 0.003).

Within groups. Greece. No differences were detected between agreement categories, since error rates in this group were consistently at zero.

Between groups. The difference between adolescents in the USA and adolescents in Greece was revealed significant in the Clitic category, with HSs in the USA producing significantly more errors in this category than their monolinguals peers (β = 0.01; SE = 0.003; t = 5.08; p < 0.0001). A similar pattern was detected in the DP internal condition (β = 0.01; SE = 0.003; t = 2.42; p = 0.02), (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Normalized frequency of errors for each agreement category (clitic, DP internal, pronoun) per country (USA, Greece) within the adolescents’ group.

To summarize, the patterns observed in the US Greek data show a systematic pattern that relates to the behavior of the clitics; we also observe that adolescent speakers show a lot of variation when it comes to DP internal agreement, i.e., attributive modifiers. The novel patterns emerging seem to affect the right part of Corbett’s hierarchy and Landau’s implementation thereof, repeated below, in a non-canonical way: we have more mismatches with personal pronouns, which is expected, and attributive modifiers, which is unexpected. Moreover, the latter do not occur in a systematic way and importantly do not conform to the expected pattern discussed above in (21a) in connection to the hierarchy in (4a–b).

| 4 | a. attributive > predicate > relative pronoun > personal pronoun |

| (article, adjective) adjective, verb | |

| formal/close agreement distant/semantic agreement | |

| b. Article > Adj 1 > Adj 2 > Adj 3 > Noun | |

| distant/semantic agreement formal/close agreement |

We note here that the very low number of errors observed with respect to relative pronouns, is due to the very low production of relative clauses introduced by pronouns marked for gender by our speakers. Lithoksoou (2019) investigated a sub-part of our US adolescent groups and noted that there is only one such production in a corpus of 40 texts and observed that these speakers prefer to use the indeclinable complementizer pu ‘that’ instead. Moreover, the high production of clitic pronouns is favored by the setting of the narration: participants had to refer back to entities introduced in the context by employing clitics.

Finally, as we do not find any sensitivity to the level of formality and/or modality (oral vs. written), we will not discuss these aspects here any further. As is shown in our examples, the data are produced in both formal and informal contexts and in oral and written mode.

6. Discussion of Our Results

Let us now turn to the two mismatches observed in the US data form the point of view of our discussion in Section 3.3, Section 4 and Section 5. We noted that the mismatches that are more frequent with both age groups are those involving clitics. Recall that in Karatsareas’s study the process of re-semanticization of gender proceeded as follows: first, the basic distinction is animate vs. inanimate, i.e., retreat to an unmarked form, followed by restructuring, that is semantic agreement with targets further away from the controller before it generalizes. Is this that we see in the USA data?12

The fact that pronoun agreement is the area that appears most vulnerable in our data could indeed be a sign of restructuring, as argued for by Karatsareas. We saw that USA Greek speakers, as already pointed out in Seaman’s study, assign different gender values to nouns than the SMG grammar. Recalls that in Greek, the only way to test gender assignment is via the use of the determiner. In (29) we see that our speaker first omits the determiner, and then she uses the neuter form. Examples such as (29) are interesting as they come from an adolescent speaker, who consistently avoids determiners, and they point to wrong gender assignment but preservation of the DC information,13 as has been noted for American Norwegian by Lohndal and Westergaard (2016). As the neuter form appears on the determiner, our speaker assigns neuter gender to this inanimate noun instead of the canonical feminine:

| 29 | Adolescent Female US bilingual speaker, formal spoken | |||||||

| pu | epeze | me | bal-a | ke otan epeze | me | to | bal-a | |

| that | played-3SG | with | ball-DC3 | and when played-3SG | with | the-NEUT | ball-DC3 | |

| ‘that was playing with a ball and while he was playing with the ball.’ | ||||||||

We can thus hypothesize that, in the grammar of Greek US adolescents, formal gender is undergoing re-analysis, as observed by Karatsareas (2011). This is supported by the following facts: We have speakers who do not resolve gender assignment by avoiding using the determiner as in (30) or use default neuter as in (29). In (30a) we see that our speaker also uses a non-appropriate case in spite of assigning the correct DC to the noun.

| 30 | a. | Adult Female US bilingual speaker, informal spoken task | ||||

| fovithike | skilo | |||||

| got scared-3SG | dog-ACC? | |||||

| ‘The dog got scared.’ | ||||||

| b. | Adolescent Female US bilingual speaker, formal written task | |||||

| ble aftokinito | kondepse | na | tus | htipisi | ||

| blue car | reached-3SG | subj | them | hit-3SG | ||

| ‘The blue car almost hit them.’ | ||||||

However, with respect to DP internal agreement, we note the following unsystematic patterns, see example (31). Note that the nouns in these examples are not hybrid nouns, i.e., they are not gender underspecified nouns:

| 31 | a. | Adult Female US bilingual speaker, informal spoken task | ||

| itan ena | mikri | ikogenia | ||

| was a-NEUT | small-FEM | family-FEM | ||

| ‘There was a small family.’ | ||||

| b. | Adolescent Female US bilingal speaker, informal spoken task | |||

| mia | alo | gineka | ||

| one-FEM | other-NEUT | woman-FEM | ||

| ‘one other woman’ | ||||

| c. | Adolescent Female US bilingual speaker, informal written task | |||

| mia | aspro | aftokinito | ||

| one-FEM | white-NEUT | car-NEUT | ||

| ‘a white car’ | ||||

In (31a) the low adjective agrees in formal gender, feminine, while in (31b) the numeral agrees in formal gender, feminine, but the intervening adjective appears in neuter. As this is a noun that is assigned gender on the basis of semantic criteria (sex), the presence of neuter on the adjective is surprising on several counts: re-semanticization would lead us to expect masculine, the default gender for animates in Greek. Moreover, it is something that Landau’s system does not predict, see (21b) above. In (31c), the determiner bears a gender which is not the appropriate default one for inanimates, i.e., the speaker uses feminine instead of neuter. In fact, the same speaker who produced (31c) later in the narration uses the correct determiner for car, but the wrong one for dog, namely feminine, again not expected under the re-semanticization point of view, see (32):

| 32 | Adolescent Female US bilingual speaker, informal written task | |||||

| to | ble | stamatise | ja | mia | shilo | |

| the-NEUT | blue | stopped-3SG | for | a-FEM | dog-DC1 | |

| ‘The blue car stopped because of a dog.’ SMG | ||||||

Similar contrasts are observed in data collected by Gavriilidou and colleagues, see Gavriilidou and Mitits (2019):14

| 33 | a. | se mia | mikros | kalathi | |

| in a-FEM | small-MASC | basket-NEUT-DC6 | |||

| ‘in a small basket’ | |||||

| b. | ena | gida | |||

| a-NEUT | goat-FEM-DC3 | ||||

| ‘a goat’ | |||||

| c. | pefti | se ena | petra | ||

| fall-3SG | on a-NEUT | stone-FEM-DC3 | |||

| ‘He fell on a stone.’ | |||||

| d. | ine | katsika | afto | pu ehi | |

| is | goat-FEM | this-NEUT | that has | ||

| ‘it is a goat that he has.’ | |||||

In (33), DC information is preserved, but both DP internal (33a–c) and DP external agreement in (33d) are non-target. While (33b–c) show the default gender for inanimates and animals, namely neuter, (31a) involves a close target surfacing with masculine gender. Such contrasts suggest to us that we have an unsystematic breakdown of the agreement system, as also observed in American Norwegian by Lohndal and Westergaard (2016), which might eventually lead to total loss of grammatical gender. Patterns such as (33) or (31c) also contradict the pattern (21b), which is supposed to have zero frequency in natural language.

In most agreement mismatches in the adult group, the situation is as in, e.g., (34), in which case formal agreement between D and n takes place as described above, but semantic agreement in phi-features is observed with external targets, namely clitics.

| 34 | i | bala | tu ksafniase | ena skilo… | ke pige ja na | to piasi | |

| the | ball | his surprised | a dog… | and went so that | it catches | ||

| ‘His ball surprised a dog who ran to catch it.’ | |||||||

To conclude, our data show that, as in the Asia Minor dialects, and acquisition studies, DP external agreement is vulnerable, and we find instances of semantic agreement. This is expected from Corbett’s Distance Principle and Landau’s syntactic implementation thereof. The DP internal patterns, however, are not systematic and do not conform to the hierarchy. Most importantly, they actually contradict the predictions made in Section 3.3.

As we pointed out, if the restructuring of the gender system follows the Distance principle, as, e.g., Dolberg (2019) and Karatsareas (2011) suggest, then we expect semantic agreement first with targets far away from the controller, and then DP internally with the adjectives that are further away from the noun. While the patterns we find with remote targets are consistent with that, the instances of mixed agreement DP internally do not provide a coherent picture and actually support the development of a system without gender agreement and the emergence of neuter as default. This could well happen under the influence of a gender-less language, namely English. If re-semanticization was taking place, we would expect sensitivity to [±human] features, which we do not observe. Moreover, we do not find consistent semantic agreement DP internally and importantly, often the most remote adjective/article formally agrees in gender with the noun, while the one closer to the noun bears semantic agreement. Taking these two together, we believe that they support the neuter as default strategy that emerges when no agreement can be established, as explained in Section 3.3. In other words, in the case of DP external agreement both groups resort to the unmarked/default option in the language, namely neuter. However, the inconsistency of DP internal agreement supports the emergence of the neuter as default strategy, because, in fact, more systematic patterns DP internally would be observed, if re-semanticization were the answer. As we saw, it is mainly our adolescent speakers who are not able to establish matching agreement chains.

Let us briefly discus some random patterns, which appear DP internally in case more than one target is used: we assume that numerals are inserted as specifiers in #P and other adjectives occupy specifier positions in DivP and nP. For each adjective, an Agree chain has to be established between the noun and the adjective. When a single target is contained, the establishment of agreement is rather effortless. As certain speakers do not resolve to the default strategy in this case, we conclude that indeed the problem is one of matching of features within the same chain, see Tsimpli and Hulk (2013), Prentza et al. (2019). When more than one element is contained, linear distance between the noun and the other targets affects the production of our speakers as argued for by Johannessen and Larsson (2015) for Heritage Scandinavian and has been acknowledged for L2 studies as well:15

Finally, we noted that DCs are preserved even in the adolescent grammar, even though English lacks DCs. We think that as in the case in American Norwegian, DC information seems relatively stable, suggesting that perhaps these are forms acquired together with the noun, as argued for by Stephany (1997) and Anderssen (2006) for Norwegian. In view of the fact that the nouns used are nouns that belong to everyday vocabulary, our speakers do not have problems with these forms.

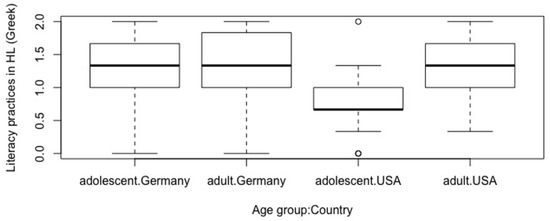

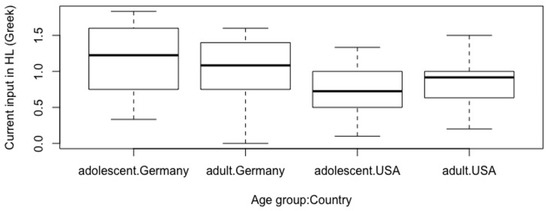

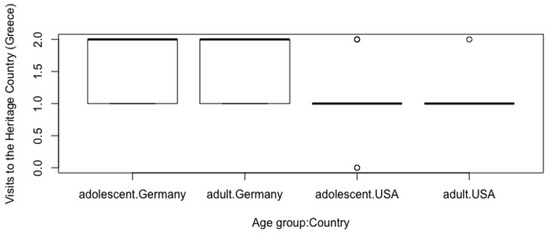

We now turn to the question of what lies behind the age group differences within the USA group, and why we do not we find practically any mismatches in the German data. Could it be related to the input for our heritage speakers? Usually, the baseline is taken to be the language of first-generation immigrants (see, e.g., Polinsky and Scontras 2020). In our study we did not test first generation immigrants, but we pointed out that if the speakers in Seaman’s study provide the input to the 2nd and 3rd generation speakers of our study, we can speculate that the baseline grammar our speaker have been exposed to is one with a rather intact gender system. We do acknowledge, however, that this is a certain limitation to our study.