Abstract

Motion events are almost absent in the course syllabus of L2 German as a formally addressed structure in the classroom. Learners have merely receptive contact with this type of structure in reading texts or in aural activities. The occurrence of motion events with the so-called “double particles” is even less frequent. These are composed of the deictic morphemes hin- and her- denoting the speaker’s perspective and Path morphemes (-ein-, -aus-, -auf-, etc.). The main goal of the present study is to test a group of Portuguese L3 learners of German regarding their knowledge of double particles, and to apply VanPatten’s Processing Instruction (PI) model (VanPatten 2004; VanPatten and Williams 2015), which rests on an input-based focus-on-form approach for teaching grammar. The theoretical framework is based on Talmy’s typology of motion events (Talmy 2000a, 2000b). The empirical component of this study was divided into three parts: first, I tested the participants by means of a pretest; then, I conducted a pedagogical intervention based on the PI model; finally, a posttest determined the successful effects of PI in the participants’ knowledge of the target forms, both in interpretative and productive contexts.

1. Introduction

In Portugal, learners of L2 German at university level demonstrate ongoing difficulties in learning the language for various reasons: their limited contact with German in non-classroom contexts, the lack of exposure to the language in their everyday lives, and the occasional deficient acquisition of certain domains of grammar. The last reason is what motivates the present study: if the traditional method is sufficient for some students to achieve a reasonable amount of linguistic knowledge but still leaves them with large proficiency gaps, even at intermediate or more advanced levels, what other methods can help the learners pull away from these acquisitional deficits and ensure better linguistic competence? Since these acquisitional problems and grammatical deficits are mostly due to the lack of contact with the target language, they are likely to form at the input level and should therefore be handled at this stage.

With this in mind, I selected an input-based pedagogical model to test the learners’ knowledge about a very specific grammatical form. VanPatten’s Processing Instruction (PI) model (VanPatten and Cadierno 1993a, 1993b) is an input-based pedagogical model that aims at correcting processing difficulties manifested by learners in a certain grammatical form. PI originated from VanPatten’s Input Processing (IP) Theory (1993, 2004, 2015), a theoretical model of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) in which the author outlines a series of processing principles related to the students’ grammatical deficits.

To test the PI model, I selected a problematic grammatical form that the learners may be able to recognize but have had very little contact with and that is not explicitly addressed in the DaF (Deutsch als Fremdsprache—German as a foreign language) curriculum. This form is a double particle used in movement structures and consists of the combination of the perspective particles hin- (‘thither’) and her- (‘hither’) with trajectory particles, e.g., -ein- (‘into’), -aus- (‘out of’). To explain the cognitive and semantic features of this specific form and its occurrences in various syntactical environments, I resorted to Talmy’s (1985, 2000a, 2000b) theoretical studies on motion events and his typological framework for event integration that divides languages into two typologically distinct groups according to motion expression: satellite-framed and verb-framed languages.

Therefore, the main goals of this study are: to see to what extent the learners recognize the target form and are able to interpret and produce it; to identify the acquisitional problems related to their faulted acquisition or non-acquisition of said form, and to determine if or in what way the PI model can be efficient in the acquisition of this form.

The present work will be structured as follows: first, I will outline the main characteristics of VanPatten’s IP Theory and PI model (Section 2); secondly, I will present a brief characterization of the structures at hand in German and Portuguese under the scope of Talmy’s theoretical framework of motion events (Section 3); then, I will present the group of participants of the present study, as well as the main research questions and hypotheses and the methodology used (Section 4); after that, I will report the results of the conducted tests (Section 5); and lastly, I will discuss the results of the tests (Section 6) and draw my final conclusions on the observed phenomena (Section 7).

2. VanPatten’s Input Processing (IP) Theory

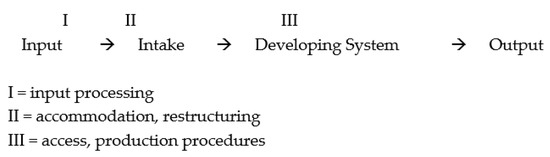

VanPatten’s Input Processing Theory (1993, 2004, 2015) has been widely used in SLA research as a means of detecting the flawed strategies learners resort to when handling grammatical information in the input. According to this theory, for a certain grammatical unit to be correctly acquired by an L2-learner, he or she must initially process it in working memory before accommodating it in the developing system to make it available for access in production. This model draws on input processing as the first of three sets of processes in SLA that comprise the transition from input to output (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Three sets of processes in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) (VanPatten 2004, p. 26).

Although VanPatten’s model of input processing has been relatively popular in the last few years and given rise to a great deal of research, there has also been some criticism that his approach leaves no room for output. VanPatten (2004) argued that his model of input processing “is not per se a model or theory of acquisition” (VanPatten 2004, p. 5) in the sense that factors related to learners’ restructuring mechanisms as well as their production of language for communicative purposes do not fall within its scope. His model targets realizing the conditions under which learners make connections between surface expression and meaning in the input and the processes they make use of to acquire grammatical data. Furthermore, the author emphasized that a focus on input does not mean that output is not relevant for acquisition. In fact, input and output “play complementary roles” in the process of Second Language Acquisition, although input represents the main source of linguistic data, since it occurs at the initial stage of acquisition.

Taking these clarifications into account, IP aims at better understanding (1) what kind of linguistic data learners attend to in the input and why, (2) what strategies lead to their form–meaning connections, and (3) why they make certain form–meaning connections before others (Wong 2004).

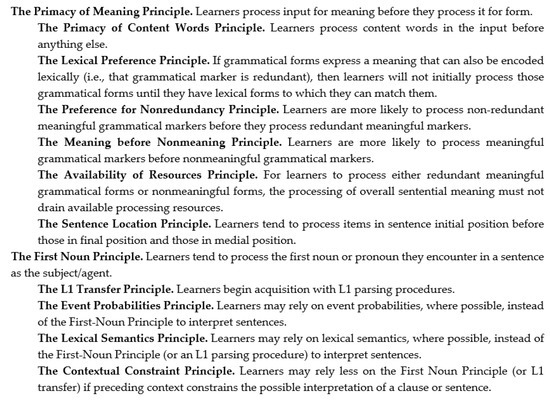

VanPatten (1997) developed a series of processing principles to illustrate the learners’ faulty strategies when processing grammatical information. These principles have since been reviewed and expanded (VanPatten 2004, 2015) and are listed in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Sets of Input Processing (IP) principles (VanPatten 2004, 2015).

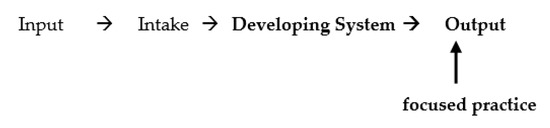

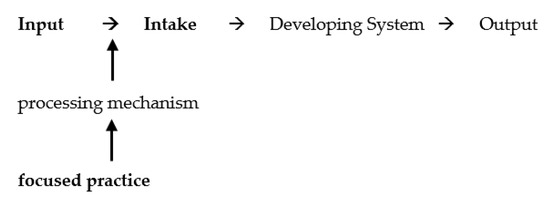

To complement his theory, VanPatten developed a pedagogical model named Processing Instruction (VanPatten and Cadierno 1993a, 1993b; VanPatten and Williams 2015; Wong 2002, 2004). Processing Instruction (PI) consists of a grammatical instruction model focused on input, which aims at driving learners away from their nonoptimal processing strategies and pushing them to make better form–meaning connections. While traditional explicit grammar instruction focuses practice at the stage of active production (see Figure 3), PI aims to train input information to convert it into intake (see Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Traditional explicit grammar instruction in foreign language teaching (VanPatten and Cadierno 1993b, p. 46).

Figure 4.

Processing instruction in foreign language teaching (VanPatten and Cadierno 1993b, p. 46).

The traditional PI approach consists of three steps: (i) the first step relies on the identification of the IP principle(s) the learners resort to when trying to process said form; (ii) the second step involves developing explicit information about the target form; (iii) the third and last step is the creation of Structured Input (SI) activities, which consist of manipulated tasks especially designed to push learners away from the previously identified processing problem(s).

Some research (Farley 2004; Fernández 2008; VanPatten and Oikkenon 1996; Wong 2004) showed that explicit information is not fundamental for the success of PI. The SI activities seem to be enough for the adequate processing of grammatical forms. However, other studies (e.g., Culman et al. 2009; VanPatten and Borst 2012; VanPatten et al. 2013) showed that explicit information can indeed be beneficial. Since the form selected for this study is mostly unknown to the learners, I chose to uphold the original framework and draw on explicit information besides the SI activities.

The first step in creating SI activities is to recognize the processing problem learners attend to when trying to process a certain form. As soon as the processing principle is identified, the limits of the SI activities are already outlined, and any SI activities created to overcome these problems have to be manipulated in order to push the learners away from resorting to said problems. In PI, we can distinguish between two types of SI activities: (i) referential, which require learners to deliver an answer that can be judged right or wrong, and (ii) affective, which aim at triggering learners’ communicative skills with regards to the target form. Some authors (Marsden and Chen 2011) claimed that referential activities are the only type of activities needed for PI to be successful, while others (Henshaw 2012) reinforced the importance of affective activities in PI. In the present study, I made use of both referential and affective activities.

3. German Double Particles in the Expression of Motion Events

Consistent with Talmy’s typology (1985, 2000a, 2000b), which aims at presenting lexicalization patterns for the expression of motion events in the world’s languages, German is considered an S-framed language, since it typically conflates Path information in a satellite element, in the form of a preposition, a prefix, or a verb particle:

| FIGURE | MOTION/MANNER | PATH | GROUND | PATH | |||

| 1 | Die | Flasche | schwebte | in | die | Höhle | (hinein) |

| The | bottle | floated | in(to) | the | cave | (thither-in) | |

| The bottle floated into the cave | |||||||

As seen in Example 1, in German, Motion and Manner information are conflated in the verb stem schwebte (‘floated’), while Path is encoded in the preposition in (‘in(to)’) or the redundant double particle hinein (‘into’). The Figure die Flasche is the entity that moves and the Ground die Höhle is the element with respect to which the Figure moves. The Ground element can be either a Goal (as in (1)), when the Figure moves towards it, or a Source, when the Figure moves away from it.

Altmann (2011) described four categories of verb particles in German. Two of these categories were later merged by Harr (2012) into one single category. The final categorization consists of three groups: (i) particle-prefixes (2a); (ii) particles derived from adverbs (2b); and (iii) the so-called double particles (2c):

| 2. a | Die | Frau | eilte | dem | Jungen | nach |

| The | woman | hurried | the | boy | ||

| The woman hurried after the boy | ||||||

| b | Der | Bergsteiger | kletterte | den | Berg | hoch |

| The | alpinist | climbed | the | mountain | up | |

| The alpinist climbed up the mountain. | ||||||

| c | Das | Mädchen | rannte | die | Treppe | hinauf. |

| The | girl | ran | the | stairs | thither-up | |

| The girl ran up the stairs | ||||||

The present study focuses only on double particles, which deliver two different kinds of information: (i) deictic information related to the speaker’s perspective, i.e., the Figure either moves away from (hin- (‘thither’)) or towards (her- (‘hither’)) the speaker; and (ii) Path information related to the trajectory of the Figure with regards to an existing Ground (e.g., -ein- (‘in’), -aus- (‘out’), -auf- (‘up’), -unter- (‘down’), -ab- (‘down’, ‘off’) and -über- (‘over’, ‘across’). Poitou (2003) suggested three construction types in which double particles can occur:

| 3. a | Constructions without Noun Phrase (NP) | ||||

| Er | geht | hinauf. | |||

| He | goes | thither-up | |||

| He goes up. | |||||

| b | Constructions with an accusative-NP | ||||

| Er | geht | den Berg | hinauf. | ||

| He | goes | the mountain-ACC | thither-up | ||

| He goes up the mountain. | |||||

| c | Pleonastic constructions with a Prepositional Phrase (PP) | ||||

| Er | geht | [hinauf] | auf den Berg | [hinauf]. | |

| He | goes | [thither-up] | on the mountain-ACC | [thither-up] | |

| He goes up on the mountain. | |||||

Contrary to German, Portuguese presents a different conflation pattern for motion events. As a V-framed language, Portuguese tends to lexicalize Path information in the verb stem, while Manner of motion is conveyed by means of a gerundival or adverbial adjunct:

| 4 | FIGURE | MOTION/PATH | GROUND | MANNER |

| A garrafa | entrou | na caverna | (a flutuar)1 | |

| The bottle | went-in | in-the cave | (to-float) | |

| The bottle floated into the cave. | ||||

This lexicalization pattern is particularly interesting for the languages of this study. At first, learners are expected to have some difficulties conveying this kind of information because their L1 has a typical lexicalization pattern that differs from that of the target language. However, since German is their L3—their L2 being English—it is expected that they establish some relation to their L2, since both English and German manifest similar conflation patterns for motion events.

4. The Present Study

4.1. Research Questions

Based on previous research on motion events and the effects of PI in classroom intervention, I put forward the following research questions:

- Can the PI model develop learners’ knowledge of the lexical–semantic properties of the target forms to a level where they are able to produce and interpret them correctly?

- Will learners have more difficulty processing the deictic information conveyed by hin- and her- or Path information expressed by -ein-, -aus-, -auf-, -über-, -unter- and -ab-?

- Is the PI effective in developing learners’ lexical–semantic knowledge, especially with regards to a form with which the learners had little to no contact?

In accordance with previous research, the group in question, and the reasons already mentioned, I put forward the following predictions to the research questions:

- The PI model is expected to be beneficial in the interpretation of the double particles and will most likely drive the learners towards attempting to produce them. However, eximious production at sentence level is not expected, since other grammatical problems (e.g., case declension, word order, prepositional selection) underlie this group’s linguistic competence.

- Learners should reveal more difficulty processing the deictic information conveyed by hin- and her- than processing Path information (-ein-, -aus-, -auf-, -über-, -unter-, -ab-), since the latter share morphological and lexical–semantic properties with other lexical elements (e.g., prepositions, adverbs) with which the learners are already familiar.

- The PI model is expected to have the positive results of other PI studies on lexical–semantic properties (e.g., Cheng 1995, 2002; Collentine 1998). Since the learners had no previous instruction in the target forms, some degree of explicit information is expected to factor into their understanding of double particles. However, since exposure to input is, in this case, reduced, learners will likely only perform well in the interpretation task.

The present study distinguishes itself from other PI research in that the target forms are of quite a different nature than those typically explored in those studies. For that reason, it contributes to the research on PI as well as on the acquisition and processing of lexical semantics.

4.2. Participants

The participants were a group of 26 students (M = 20.55; SD = 1.36) in both the second and third years of studies in Applied Languages and European Languages and Cultures at the University of Minho, Portugal. All participants in the study were completing the B1 level of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) at the time of testing.

An adapted Bilingual Language Profile (BLP)2 (Birdsong et al. 2012) was used to assess the participants’ language dominance in the languages tested, which were their L2, English, and their L3, German. The BLP determined that most of the participants started studying German at university level, while some started in high school. Only one participant had lived in a German-speaking country, having returned in early childhood.

The BLP also provided some insight about the language dominance of the participants. In the scoring system of the BLP, the participants can achieve a maximum total of 218 points in each language and the language dominance index consists in the subtraction of the total score of one language from the other. The mean score in English was 138.4 (SD = 18.1) with a minimum individual score of 113.6 points and a maximum individual score of 174 points. In German, the participants had a mean score of 60.9 (SD = 22.3) with minimum and maximum individual scores of 25.7 and 109.9 points, respectively. The mean language dominance score was 77.41 (SD = 29.58), which means that the participants had a considerably higher competence level in English than in German.

Further analysis of the questionnaire showed that the participants considered themselves to have great difficulty with German at a production level, in comparison with their L2. It should be noted that these students had very limited contact with German in their daily lives. Virtually none of the participants used the language in environments other than classroom contexts. However, most participants revealed an interest in learning German for academic and professional purposes due to its present socioeconomical status, and showed some identification with the German-speaking cultures.

4.3. Methodology

The empirical approach of the present study was threefold: (i) a pretest consisting of a lexical decision task, a production task, and a multiple-choice recognition task; (ii) a PI classroom intervention consisting of three sessions; and (iii) a posttest consisting of a production task and a binary-choice recognition task.

4.3.1. Pretest and Posttest

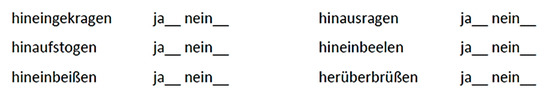

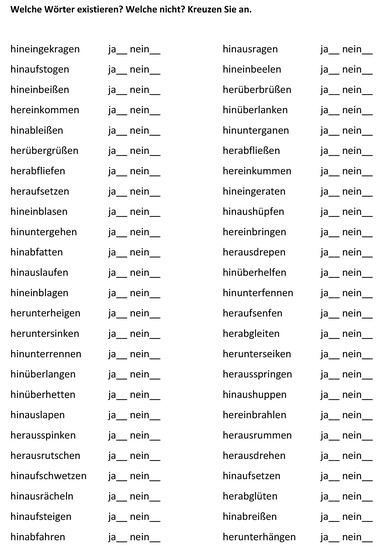

The lexical decision task was solely used in the pretest and aimed at assessing the level of language proficiency of the participants by means of determining their vocabulary size with regards to the target form. The task consisted in a modified version of the Dialang Vocabulary Placement Test (see Alderson 2005) and presented 50 verbs with double particles, 25 of which were invented. For the non-existing words, only the verbs were invented, the particles remained correct (see Figure 5). The group was, therefore, meant to determine whether the word existed or not (see Appendix A).

Figure 5.

Example from the lexical decision task.

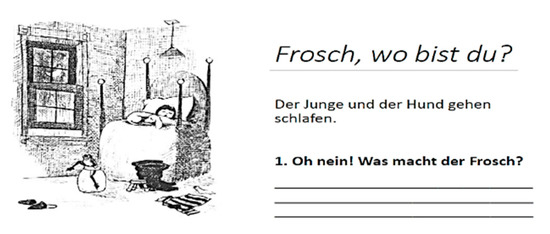

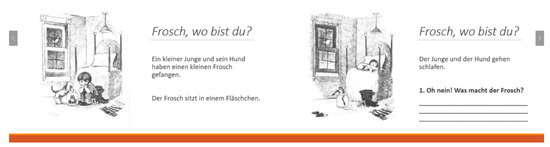

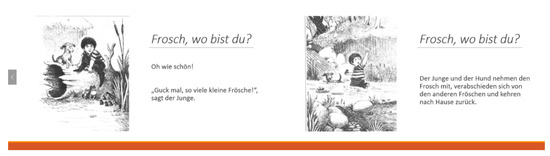

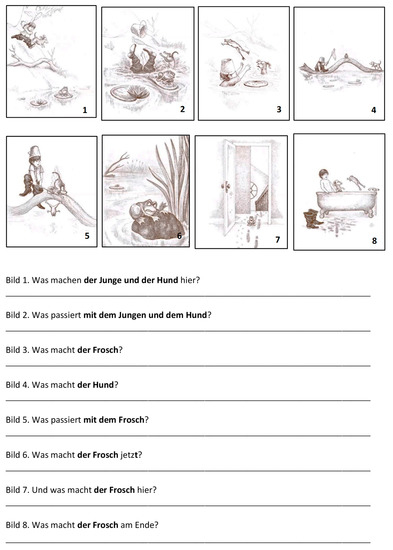

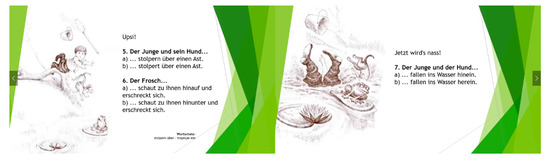

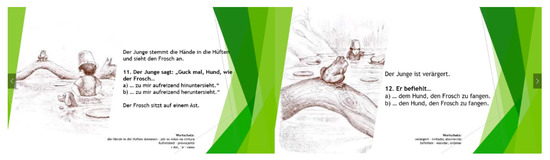

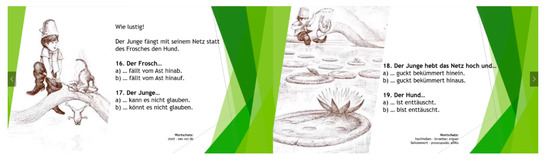

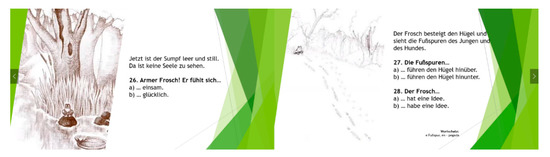

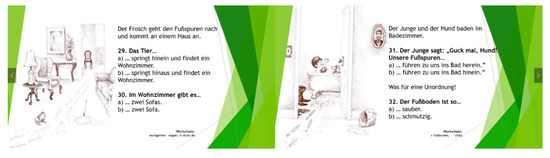

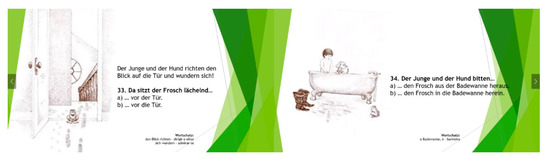

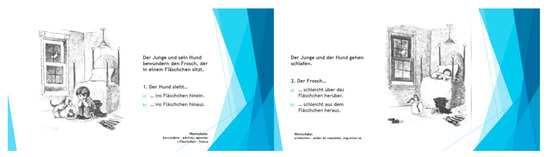

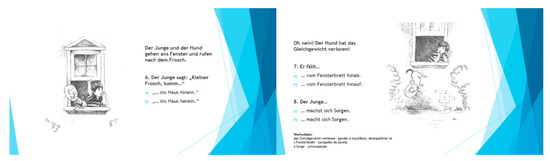

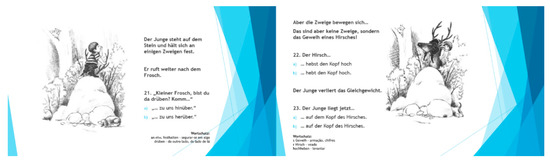

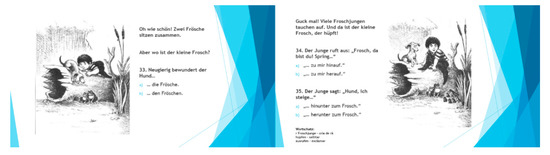

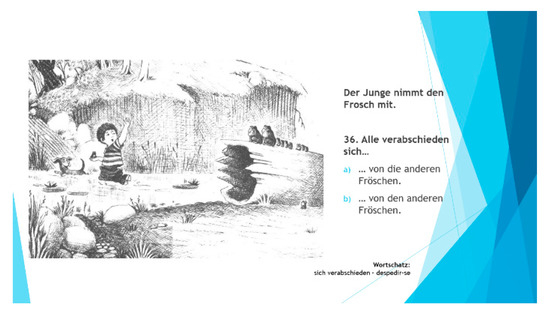

To test their production of the double particles in both the pretest and the posttest, the participants were presented with an image-induced production task based on the volumes Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer 1969) in the pretest (see Figure 6), and A Boy, a Dog and a Frog (Mayer 1967) in the posttest, from Mercer Mayer’s acclaimed series Frog Stories3. The task consisted of eight questions related to several illustrations from the book in which the participants were prompted to produce movement structures to describe the events happening in the pictures (see Appendix B). The notion of perspective (hin- and her-) was ignored in this task, since it rests on the speaker’s viewpoint and is not clear in indirect speech:

Figure 6.

Example from the production pretest.

As for interpretation, a binary-choice recognition task was applied to verify if the participants recognized the semantic value of the double particles in both the pretest and the posttest. The participants were prompted to answer a question or complete a sentence with one of two choices. As a reviewer pointed out, this assessment method is not ideal because it sets the participants’ accuracy at 50%. However, given the learning background of the group under study, a regular Grammaticality Judgment Task would not deliver very clear results either, as far as the pretest goes. Despite skepticism, this methodology proved quite successful in the posttest, when the participants were already familiarized with and had already been instructed on the target forms.

Of the two choices, the incorrect choice could be fully ungrammatical or simply unsuited to that given context. The visual aid was deemed essential to deliver the notions of speaker’s perspective and Path in the task items. To that end, I swapped the picture stories of the production task and used A Boy, a Dog and a Frog (1967) in the interpretation pretest and Frog, Where Are You? (1969) in the interpretation posttest. Direct speech was also occasionally used in order to avoid ambiguity in terms of the speaker’s perspective.

The interpretation tasks consisted of two conditions and six subconditions with three binary-choice items per subcondition, which made up a total of 18 items with 18 distractors. In sum, there were 36 answer possibilities for the target items. In Table 1, I outline the conditions of the interpretation task and present some examples used in the pretest (see Appendix C for the complete tasks).

Table 1.

List of conditions/subconditions of the binary-choice recognition task with examples from the pretest (correct answers highlighted in bold).

The results of the pretest and the posttest were analyzed using the IBM SPSS 25 software for statistical treatment. Upon collection, data were tested for normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Afterwards, parametric or non-parametric difference tests within subjects were used for the various conditions, based on whether data distribution was normal or not.

4.3.2. PI Classroom Intervention

The classroom intervention consisted of three modules: (i) the first intervention outlined the morphological characteristics of the double particles, including the semantic information of perspective and Path they encode; (ii) the second intervention focused on the combinations of said particles with verbs of motion and other verbs that acquire this trait; and (iii) the third and last intervention presented their syntactic properties in sentential environment.

Each module lasted one hour to one hour and thirty minutes and consisted in an initial explanation of the target form and the faulty strategies learners resort to when trying to process it, and a set of SI activities. The modules were conducted in three separate sessions for the approximate period of two weeks.

As pointed out by some authors (Farley 2004; Fernández 2008), the most important step for the success of the PI intervention is the SI activities. Upon analysis of the pretest (see Section 5.2), I verified that the participants did not produce double particles in active contexts, even when they were prompted to do so. This came as no surprise, since double particles are rarely present in the German curriculum for foreign learners and are mostly used in formal contexts. In my search for potential processing principles for the SI activities, I resorted to the interpretation task to determine what strategies learners may have attended to when trying to interpret the target form.

I was able to narrow them down to three possible processing principles: the Preference for Nonredundancy Principle, the Availability of Resources Principle, and the Sentence Location Principle. The examples (5) to (7) are items from the recognition task that show how learners resorted to these principles when interpreting the sentences. The parts indicated in bold are the answers erroneously selected by some participants in the binary-choice items.

| 5 | The Preference for Nonredundancy Principle | ||||||||||

| *Mittlerweile | legt | der | Junge | seine | Hand | und | seinen | Fuß | auf | ||

| Meanwhile | puts | the | boy | his | hand | and | his | foot | on | ||

| den Ast | und | versucht | aus | dem Wasser | hereinzukommen | ||||||

| the branch | and | tries | out-of | the water | hither-in-to-come | ||||||

| 6 | The Availability of Resources Principle | ||||||||||

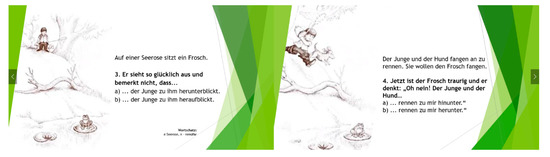

| *Jetzt | ist | der | Frosch | traurig | und | denkt: | Oh nein! | Der | |||

| Now | is | the | frog | sad | and | thinks | oh no | the | |||

| Junge | und | der | Hund | rennen | zu | mir | hinunter. | ||||

| boy | and | the | dog | run | to | me | thither-down | ||||

| 7 | The Sentence Location Principle | ||||||||||

| *Der | Frosch | fällt | vom | Ast | hinauf. | ||||||

| The | frog | falls | from-the | branch | thither-up | ||||||

In (5), we observe that the preposition aus (‘out of’) already expresses outward motion and, therefore, the use of the double particle is redundant. The participants who failed to make the connection between the preposition and the particle heraus- (which conveys outward movement towards the speaker) selected the option herein- (which, on the other hand, conveys inward movement). What pushed learners to make this decision may have something to do with the Preference for Nonredundancy Principle, since they chose to ignore the redundant grammatical value of the double particle. The fact that the target form appeared in the final position in most items of the recognition test could have also driven the learners to pay less attention to it, which meets the Sentence Location Principle, present in items (5)–(7). According to this principle, items that appear in medial or final position are less likely to be correctly processed by the learners. Another important processing problem ties in with the Availability of Resources Principle exemplified in (6). Items with too much information seemed to drain participants’ processing resources.

It should be noted that these processing principles are interdependent and do not operate alone. Although three main problems were identified, it is possible that some learners resorted to other less salient faulty strategies to make sense of the sentences. Likewise, since the learners showed some unfamiliarity with the target forms at first, it is also possible that some of their answers were arbitrary or derived from contextual cues (e.g., the deictic values of the verbs kommen (‘to come’) and gehen (‘to go’), as mentioned above). Since the interpretation task was applied by means of binary-choice items, this cannot be precisely concluded in the pretest.

The SI activities developed for the three sessions included a consistent set of adventures with the same main character, Anna. The following examples show how the guidelines for the PI interventions were carefully followed for the focused practice to be as efficient as possible in circumventing defective strategies. The task demands presented here are translated. The original activities were described in the participants’ L1, Portuguese, to drive them away from possible misinterpretations:

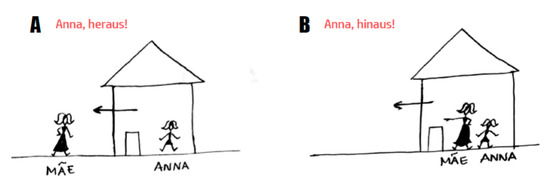

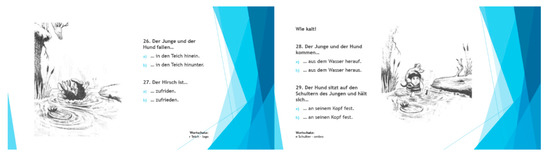

Activity A. Anna and her mother. Anna’s mother is angry and commands her to do things. Look at the pictures and listen to the mother’s commands. Which picture corresponds to each command?

| MODEL: | (you hear) | Anna, heraus! |

| (you say) | Picture A. |

The first activity was a picture-driven referential aural task. The instructor said aloud the mother’s command and the learners were presented with two pictures and said which picture corresponded to said command (A or B). The learners had to pay attention to the form of the double particle and establish the right form–meaning connections, according to the stimuli prompted by the images. Primarily, they had to consider the deictic component of the target form and afterwards pay attention to the Path component of the particle in order to assign the command to the right picture. Notice that the activity involved the recognition of an interjection, which meant that the learners did not need to produce the target form, but simply make the right form–meaning connections between the utterance and the movement depicted in the corresponding picture (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Example of the pictures used in Activity A of the first module.

Using the same pictures, learners were driven to distinguish Path information in Activity B. This was a written referential binary-choice task in which learners had to make the same form–meaning connections by associating the image with the corresponding option. Notice how the previous short interjections from Activity A moved to simple imperative sentences (Activity B). Double particles were also the first and only element the learners encountered in each point, which made it easier for them to pay attention to the lexical–semantic features of the target form.

Activity B. Anna’s mother. Anna’s mother keeps on commanding her to move. Look at the pictures and tick the right option, according to what you think she might be telling her.

| Anna, komm bitte… (Anna, please come…) | |

| A. a. ___ heraus | b. ___ herein |

| B. a. ___ herein | b. ___ herunter |

| (…) | |

| Anna, geh bitte… (Anna, please go…) | |

| E. a. ___ hinunter | b. ___ hinauf |

| F. a. ___ hinüber | b. ___ hinauf |

| (…) | |

Activity C. Anna und Benjamin. Step 1. Benjamin describes Anna’s path when they were playing in his house. Pay attention to the particle and complete with “Anna geht” (‘Anna goes’) or “Anna kommt” (‘Anna comes’), according to his perspective.

| __________________ hinein. |

| __________________ hinauf. |

| __________________ heraus. |

| (…) |

As observed, the input moved from interjections in Activity A to short sentences in Activity B and C. In the first step of this activity, learners needed to pay attention to the speaker’s perspective expressed by the morphemes hin- and her- in the double particles in order to complete the sentences. This deictic notion was also expressed by the verbs gehen (‘to go’) and kommen (‘to come’), which helped the learners make the appropriate form–meaning connections. The particle was the first and only element the learners encountered when attempting to solve the task, which ties in with the Sentence Location Principle, meaning that learners could dedicate their processing resources to the target form only. Thereby, learners only had to complete the sentence with Anna geht (‘Anna goes’) or Anna kommt (‘Anna comes’), according to Benjamin’s perspective of Anna’s movement. Notice that no Ground element was expressed to avoid the use of redundant elements in the sentence, which could elicit the Preference for Nonredundancy Principle or drain the learner’s processing resources.

Activity D. Anna’s Routine. Read the following sentences related to some of Anna’s daily trajectories. Are your daily trajectories the same as hers?

| Anna ist in ihrem Zimmer. (Anna is in her bedroom.) | ||

| Sie geht… (She goes…) | Yes | No |

| 1. hinaus zum Flur. (out to the hallway.) | ____ | ____ |

| 2. hinauf zum Bad. (up to the bathroom.) | ____ | ____ |

| (…) | ||

| Anna ist vor der Schule. (Anna is in front of the school.) | ||

| Sie kommt… (She comes…) | Yes | No |

| 1. herein zur Halle. (inside to the hall.) | ____ | ____ |

| 2. herauf zum 2. Stock. (up to the second floor.) | ____ | ____ |

| (…) |

Activity D of the first set of SI activities was an affective activity, which meant that learners were not required to give right or wrong answers, but rather to connect the fictional events in the activity with events of the outside world, focusing on their real-life experiences. Learners needed to pay attention to the double particles to understand the meaning of utterances. Notice how the Preference for Nonredundancy Principle was contemplated: the motion events consisted in the expression of a Goal highlighted by the preposition zu (‘to, towards’), therefore avoiding pleonastic constructions with derivative prepositions (such as aus (‘out of’), in (‘into’), and auf (‘up’)) that could trigger this principle. Consequently, these double particles do not express redundant information and are necessary for the learners to understand the courses of Anna’s motion towards her Goal. The Sentence Location Principle was also considered: the sentences were manipulated, so that the particle would be the first element learners encountered in each point.

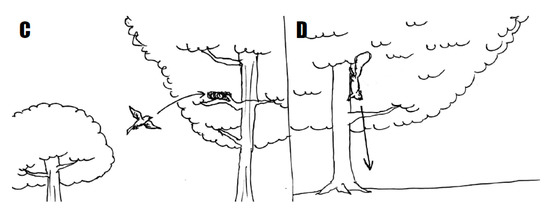

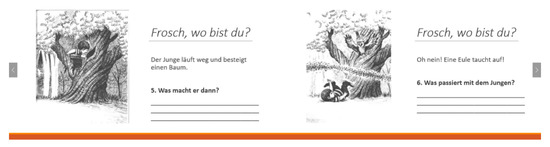

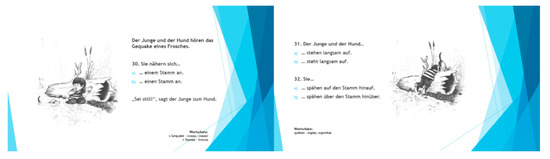

The second session consisted in a more complex approach to double particles, in their combination with manner-of-motion verbs, i.e., verbs that conflate both Motion and Manner, which are particularly common in German, but not as productive in Portuguese (see an example of the visual aid in Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Examples of the pictures used in Activity B of the second module. C: Der Spatz fliegt hinauf; D: Das Eichhörnchen steigt hinab.

Activity B. In the City Park. Anna went for a stroll in the city park with Benjamin and Bianca. She sees several animals and describes their movement to her friends.

| Bianca, guck mal! (Bianca, look!) | ||

| A. Der Hund rutscht… (The dog slips…) | a. ___ hinunter | b. ___ hinauf |

| B. Der Frosch hüpft… (The frog hops…) | a. ___ hinein | b. ___ hinaus |

| C. Der Spatz fliegt… (The sparrow flies…) | a. ___ hinüber | b. ___ hinauf |

| D. Das Eichhörnchen steigt… (The squirrel climbs…) | a. ___ hinab | b. ___ hinauf |

| (…) |

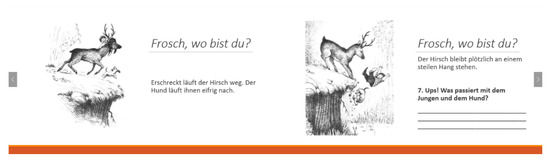

The focus of the third session was the syntactical environment of verbs of motion with double particles. Here, I presented the learners with the three possible occurrences of such motion events, i.e., intransitive constructions, transitive structures with accusative-NP, and pleonastic constructions with PP:

Activity D. “You’re in trouble!” The kids’ mother had already noticed that Anna is overwhelmed by them. Pay attention to her commands and choose the right answer, according to what she may be telling them.

| 1 | Steigt _______________ herunter! | a. vom Baum (off the tree) |

| (Climb… down!) | b. auf den Baum (up the tree) | |

| (…) |

In this activity, the learners were required to choose the right answer in the binary-choice items. The options consisted of two PPs with Ground information, through which they needed to pay attention to both the speaker’s perspective and Path components of the double particles to deduce which expression was more fitting in the given examples. Here, they had to resort to what they learned about prepositional selection in the third module, but only as a way of interpreting the target form.

5. Results

In this section, I will be showing and comparing the results of the conducted tasks: the lexical decision task, the production tasks, and the binary-choice recognition tasks.

5.1. Lexical Decision Task

The sole purpose of the lexical decision task was to provide the tester with some information about the participants’ language proficiency and recognition of the target forms.

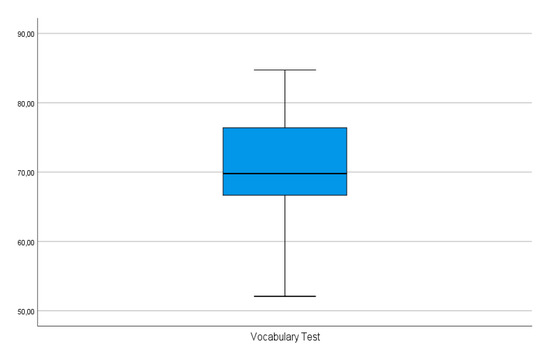

According to Figure 9, we can see that the participants had an intermediate level of German. The lowest single value was 52% and the highest single value was 85%, with an overall mean value of 70% (SD = 7.9). If we analyze the two groups of words separately, we can conclude that the tested group had a higher success rate in the nonexistent words (75%) than in the existent words (62%), which implies that the learners have more difficulty determining if a word exists rather than the opposite.

Figure 9.

Boxplot: Results of the lexical decision task.

The test also showed some variation in the overall acceptance of the different double particles presented to the participants. According to the results, the testees are more inclined to correctly determine if a verb with a double particle introduced by her- (‘hither’) exists or not (75%), rather than a verb with double particle introduced by hin- (‘thither’) (66%). In terms of Path, they tend to have more difficulty determining the existence of verbs with double particles composed of -aus- (‘out’) (64%) than those composed of -ein- (‘in’) (76%). This reveals a tendency that can be explained by prior contact with similar forms in classroom contexts, whether in textbook reading texts or in certain aural activities.

5.2. Production Task

In both the pretest and the posttest, production took place before interpretation (and before the lexical decision task in the pretest), so that the participants would not be influenced by the occurrence of the target form. It should be noted that not all the participants were present for assessment in the production pretest and posttest. In the production pretest, only 22 (84.6%) out of the 26 participants performed the task, in the posttest, only 17 (65.4%). The analysis of both the production and interpretation tasks was based on the existing results, excluding the missing values.

The production task revealed five patterns of answers: evaded answers, in which the participants avoided the motion construction, resorting to other elements present in the pictures; intransitive motion events (MEs), in which they avoided Path information; intransitive MEs with double particles (DPs) (only present in the posttest); motion events with PPs; motion events with PPs and DPs, and blank answers (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the types of answers in the production pretest and posttest.

In the production pretest, the participants did not actively use double particles in their description of motion events in German. It is not clear if they were aware that these particles exist or if they remembered them from previous encounters with the form in receptive classroom contexts, but they tended to ignore Path information altogether and focus on movement (8) or express Path in a satellite preposition (9). In the latter case, the participants sometimes failed to select the correct preposition for the Path information they were trying to convey (10), which shows other grammatical problems underlying motion events in their L3, as exemplified by the answers below:

| 8 | Die | Bienen | fliegen. |

| The | bees | fly | |

| The bees are flying.’ | |||

| (Participant 18) | |||

| 9 | Sie | fallen | vom | Hang |

| They | fall | from-the | slope | |

| They are falling down the slope.’ | ||||

| (Participant 7) | ||||

| 10 | Der Junge | fällt | *auf | *die | Baum |

| The boy | falls | on | the-FEM | tree | |

| The boy falls down the tree | |||||

| (Participant 20) | |||||

The results of the production posttest showed that the learners in general produced (or attempted to produce) answers with double particles more frequently in relation to the production pretest, in which the target form was used only once by one participant (0.6%). The mean of evaded answers decreased (from 28.4% in the pretest to 18.4% in the posttest) and the participants performed considerably fewer intransitive structures (from 13.1% to 3.7%). The items with no answer were also much less (from 8.5% to 0.8%), which seems to show that the participants felt a little more confident executing the task. Furthermore, the use of double particles increased considerably: 56.6% of the answers contained double particles, while only 43.4% avoided the target forms.

Further analysis showed that there are no significant differences between the use of the answers with DPs (56.6%) and the answers without DPs (43.4%) in the production posttest. This was confirmed by means of a non-parametric Wilcoxon test for two related samples (Z = −0.749, p = 0.454). In the answers with a double particle, 42.9% contained the deictic component hin-, while 57.1% made use of particles with her-. The participants seem to show a preference for the deictic component her-, which expresses movement towards the speaker, but a non-parametric Wilcoxon test for two related samples revealed no statistically significant differences between the choice of the participants for hin- or her-particles in their answers (Z = −0.789, p = 0.430). Their tendency to prefer her- over hin- is unlikely to be based on frequency, since the particle hin- occurs more frequently than the particle her- (see Goldhahn et al. 2012). Therefore, this preference could be due to the participants’ own perspective and interpretation of the picture.

5.3. Binary-Choice Recognition Task

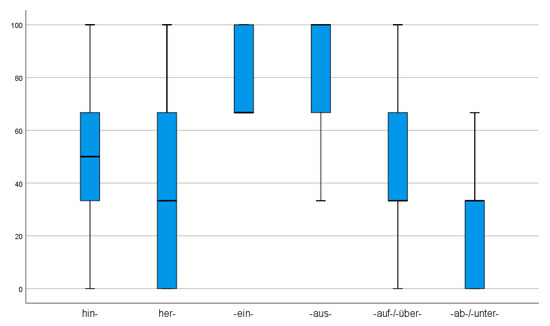

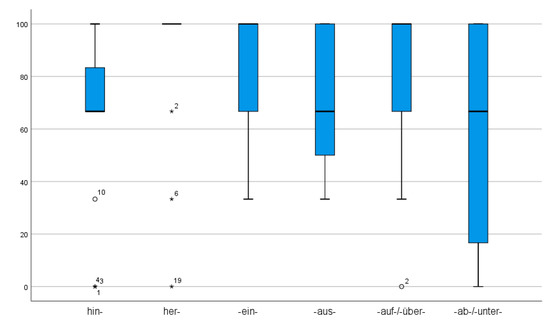

The interpretation task was performed by 22 (84.6%) out of the 26 participants in the pretest and by 24 (92.3%) in the posttest. The range of partial means in the interpretation pretest consisted of the minimum individual value of 36% and maximum value of 72%. The overall mean value was 54% (SD = 8.9). As for the posttest, the mean success rate was 75.9% (SD = 16.3) with a minimum individual value of 33.3% and a striking maximum individual value of 100%. The boxplot in Figure 10 presents the results per subcondition in the pretest and the boxplot in Figure 11 presents the results per subcondition in the posttest:

Figure 10.

Boxplot: Results of the interpretation pretest per subcondition.

Figure 11.

Boxplot: Results of the interpretation posttest per subcondition.

In the interpretation pretest, hin- had a mean score of 53.8% (SD = 25.1) and her- a mean score of 39.4% (SD = 31.2). Subconditions B had the following results: -ein- with a mean score of 77.3% (SD = 15.5); -aus- with a mean score of 86.3% (SD = 19.2); -auf-/-über- with a mean score of 49.9% (SD = 31.3), -unter-/-ab- with a mean score of 19.7% (SD = 19.2). Subconditions A (hin-/her-) revealed a mean score of 46.6% (SD = 17.7) with minimum and maximum individual values of 16.7% and 83.3%, respectively, and Subconditions B had an overall mean score of 58.3% (SD = 9) with a minimum individual value of 41.7% and a maximum individual value of 66.7%.

These values reiterate that the participants have a weak knowledge of the target form. A non-parametric4 Wilcoxon test for two related samples showed that there were significant differences between learners’ knowledge of the speaker’s perspective and their knowledge of Path information (Z = −2.474, p = 0.013), that is, the participants had more difficulty distinguishing the deictic notion of perspective (hin-, her-), than distinguishing the notion of Path in the double particle (-ein-, -aus-, etc.).

Another Wilcoxon test for two related samples showed that there is no evidence for a difference between the interpretation of hin- and her- in the double particles (Z = −1.362, p = 0.173). Nevertheless, a non-parametric Friedman test revealed that there were statistically significant differences among the Subconditions B (χ2 = 39.846, p < 0.001), e.g., the participants are more susceptible to double particles encoding inward/outward movement (-ein-, -aus-) than those encoding upward/downward movement (-auf-, -unter-/-ab-) and transition/crossing (-über-). With regards to the participants’ proficiency, upon verifying normality in the overall mean scores of the lexical decision task and the interpretation pretest, a Pearson correlation (r = 0.200, p = 0.373) showed that there is no evidence for a correlation between these variables.

In the interpretation posttest, hin- had a mean score of 65.3% (SD = 30.3) and her- a mean score of 91.7% (SD = 24.6). As for Subconditions B: a mean score of 86.1% (SD = 21.8) for -ein-; 69.5% (SD = 25.9) for -aus-; 80.6% (SD = 25.8) -auf-/-über-; and 62.5% (SD = 42.1) -ab-/-unter-. Both Subconditions A had a collective mean score of 78.5% (SD = 19.3) with minimum and maximum values of 33.4% and 100%, respectively; the Subconditions B had a collective mean score of 74.7% (SD = 19.1) with a minimum individual value of 33.3% and a maximum individual value of 100%.

To check if the differences among the Subconditions in the interpretation posttest are statistically significant, I conducted a series of non-parametric difference tests upon verifying non-normal data distribution. A Wilcoxon test for two related samples revealed that there is no evidence for differences between Condition A (speaker’s perspective) and Condition B (Path): (Z = −1.029, p = 0.303).

For Subconditions A (hin-, her-), a non-parametric Wilcoxon test for two related samples revealed that there are indeed differences between the participants’ interpretation of the deictic components (Z = −2.494, p = 0.013), i.e., participants seem to have more difficulties understanding the semantic properties of hin- (‘thither’) than those of her- (‘hither’).

A non-parametric Friedman test showed that there are significant differences between the Subconditions B (χ2 = 9.446, p = 0.024). This test, however, did not provide information on where these differences lie. To obtain specific information about these discrepancies, I conducted a series of non-parametric Wilcoxon tests for two related samples. The results are presented in Table 3:

Table 3.

Results of a series of Wilcoxon tests concerning Subconditions B in the interpretation posttest.

The results of the Wilcoxon tests displayed in Table 3 revealed that there are significant differences between -ein- and -aus- (Z = 2.265, p = 0.023), -ein- and -ab-/-unter- (Z = 2.287, p = 0.022), and -aus- and -auf-/-über- (Z = 2.034, p = 0.042). Upon application of the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, -ein- should reach significance at 0.016, since it was involved in three separate comparisons, and -aus- should reach significance at 0.025, since it was involved in two. This correction shows that there is no evidence for differences among the Subconditions B, when compared individually.

A non-parametric Wilcoxon test for two related samples (Z = −3.511, p < 0.001) showed a significant difference between the learners’ initial knowledge of the target form and their knowledge after the classroom intervention took place. Table 4 summarizes the development of the participants from the pretest to the posttest in each condition/subcondition:

Table 4.

Results of a series of Wilcoxon tests for the Conditions and Subconditions of the binary-choice recognition task in the pretest and the posttest.

As displayed in Table 4, both Conditions A (hin-, her-) and B (-ein-, -aus-, etc.) revealed significant differences between the values of the pretest and the values of the posttest. Almost every Subcondition, with the exception of hin- (Z = −1.228, p = 0.220) and -ein- (Z = −1.137, p = 0.256), manifested the same proclivity, which means that the classroom intervention had a determining role in the learners’ understanding of the target form, which was substantially more developed in the posttest.

It should be noted that not all participants received explicit information about the target form and executed the corresponding SI activities. Three classroom interventions were conducted, and the corresponding SI activities were performed in loco by the participants who were present. Those who could not attend the classes were provided with the explanation and sets of activities of the sessions they missed and had to complete them at home and submit them to the instructor, but not all of them did so. The first and second modules of explanation and SI were completed by 25 out of the 26 participants (both 96.2%), the third by 23 (88.5%) only.

To check if these variables had an effect on the participants’ performance in the posttest, I cross-referenced the mean success rates of the answers with double particles in the production posttest and the mean success rate of the interpretation posttest with the mean percentages of exposure to all three modules (whether in classroom context or as homework). A Spearman’s correlation showed that there is no association between the level of exposure and the success rates of the production posttest (rs = 0.049, p = 0.853), but that there is a strong association between the amount of exposure and their performance in the interpretation posttest (rs = 0.502, p = 0.012), which means that the participants who completed all three modules had better results at the interpretation level. Another Spearman’s correlation showed that there are also strong associations between the participants’ completion of the three modules and their performance in Condition A (rs = 0.434, p = 0.034) and Condition B (rs = 0.521, p = 0.009) of the posttest.

6. Discussion

The results of the posttest, coupled with the PI intervention and the results of the pretest, allow us to draw some conclusions about the pertinence of the present study and the efficiency of the methodology used for the acquisition of the target forms. The initial hypotheses and suppositions were essentially met. In this section, I will provide general answers to the research questions and confront the results with the initial hypotheses to achieve an overview of the observed phenomena.

Question 1.

Can the PI model develop learners’ knowledge of the lexical–semantic properties of the target forms to a level where they are able to produce and interpret them correctly?

Hypothesis 1.

The PI model is expected to be beneficial in the interpretation of the double particles and will most likely drive the learners towards attempting to produce them. However, eximious production at sentence level is not expected, since other grammatical problems (e.g., case declension, word order, prepositional selection) underlie this group’s linguistic competence.

In response to the first research question and congruent with the corresponding hypothesis, the PI did indeed have very positive effects on the participants’ knowledge of the target form. In the case of production, the participants started using double particles while expressing movement. They seemed to attend to the lexical–semantic properties of the target form, but still could not convey a syntactically faultless sentence because they lacked basic understanding of other grammatical domains. The production posttest revealed 56.6% of answers with double particles, in 80.5% of the cases used correctly. This shows that the learners gained some knowledge about the usage of the target form and slowly started applying it to specify Path. Although the participants started using double particles to describe movement in the pictures, they still favored intransitive structures, in which they did not need to specify Ground information. A possible reason for this may be the fact that they do not feel comfortable producing movement structures with specific Source or Goal elements since they need to apply specific grammatical rules that are not yet fully acquired (e.g., case declension, prepositional selection, etc.). As previously mentioned, speaker’s perspective could not be assessed in production because it was hard to determine. However, it could be assumed that the participants interpreted the pictures according to their own perspectives, since they tended to favor movement towards the speaker with her-particles (56.5%) over movement away from the speaker with hin-particles (43.5%).

At interpretation level, the PI model had much more striking effects. The participants seem to have understood the properties of the double particles and the notions of speaker’s perspective (expressed by hin- and her-) and Path information (expressed by -ein-, -aus-, -auf-, -über-, -unter- and -ab-) to an adequate level. Comparing the results of the interpretation posttest with those of the pretest, learners manifested an astonishingly better knowledge of the deictic particle her- in comparison with the pretest (91.7% against 39.4%). In the items with hin-, there were no significant differences. As pointed out by a reviewer, this could be due to the participants’ higher pretest scores and the forced-choice interpretation task, which gave them a 50/50 chance of accuracy. The participants also revealed significant differences in their knowledge of the Path component of the double particles, except for -ein-, which was mostly correctly interpreted in the pretest (86.1% in the posttest against 77.3% in the pretest). The completion of all three PI modules also seemed to play a role in the development of the participants’ competences.

These results do not provide enough evidence to suggest that the PI model is a more effective method for acquiring lexical–semantic information than traditional methods, mainly because these more traditional approaches were not tested in the course of the present study. However, based on the positive effects of the posttest, the effectiveness of PI as a valid instruction model is undeniable. Not only did the participants start understanding a form they had barely been exposed to, but they also attempted to produce it at sentential level despite their general difficulties with motion structures.

Question 2.

Will learners have more difficulty processing the deictic information conveyed by hin- and her- than Path information expressed by -ein-, -aus-, -auf-, -über-, -unter- and -ab-?

Hypothesis 2.

Learners should reveal more difficulty processing the deictic information conveyed by hin- and her- than processing Path information (-ein-, -aus-, -auf-, -über-, -unter-, -ab-), since the latter share morphological and lexical–semantic properties with other lexical elements (e.g., prepositions, adverbs), with which the learners are already familiar.

Concerning the second research question: in the pretest, learners did not produce the structure and their interpretation of the DPs was probably due to chance. However, they showed a tendency to have more difficulty recognizing deictic information encoded in hin- and her- than recognizing the Path morpheme of the DP, which seems to show that the participants resorted to their intralinguistic knowledge to make an association between some of the Path elements of the DP and other morphologically similar lexical items they were already familiar with. For the perspective elements hin- and her-, this did not seem to be the case and most answers appeared arbitrary.

In the posttest, nevertheless, deictic information was not able to be assessed at production level, but the learners manifested a tendency to favor her-particles over hin-particles. This tendency was reiterated in interpretation, since the success rate of her- was significantly higher than that of hin-. On the other hand, differences between the values of speaker’s perspective and Path were not significant in the posttest, which reiterates the positive effects of the PI model, since it contributed to make dominance of both semantic elements well-balanced.

Question 3.

Is the PI effective in developing learners’ lexical–semantic knowledge, especially with regards to a form with which the learners had little to no contact?

Hypothesis 3.

The PI model is expected to have the positive results of other PI studies on lexical–semantic properties (e.g., Cheng 1995, 2002; Collentine 1998). Since the learners had no previous instruction in the target forms, some degree of explicit information is expected to factor into their understanding of double particles. However, since exposure to input is, in this case, reduced, learners will likely only perform well in the interpretation task.

The PI model does indeed prove itself pertinent to the domains of L2/L3 Learning and Grammar Instruction. The present study along with several others (e.g., Cheng 1995, 2002; Collentine 1998) shows that PI has positive effects on the acquisition of lexical–semantic information of grammatical forms. To my knowledge, however, no other study has attempted at testing a form the learners had never been instructed about, and possibly never encountered. Given the guidelines of PI and the forms and methodology usually selected for this kind of research, the circumstances of this study were rather unorthodox, but we could still obtain quite satisfying results for both the production and interpretation tasks and show that PI can serve as a baseline model for “new” grammatical forms or structures. Even one month after instruction, the participants demonstrated a much higher understanding of double particles at word level. At sentential level, the participants still manifest various problems in several grammatical domains to be able to seamlessly perform these structures involving double particles. Still, they seem to be able to discriminate the semantic properties of said particles and interpret them in the input. A longitudinal study, for example, would be more precise in testing if the use of the PI model for new lexical–semantic information helps crystallize it in working memory and favors acquisition. The type of study developed, the tested group, and the context of acquisition prevent us from making this assumption.

7. Conclusions and Open Questions

Motion events per se are already downgraded in the curriculum of German as a foreign language, especially given the complex intricacies they entail, and movement structures with double particles are hardly ever directly handled in instruction. The reduced contact learners have with such structures—which are relatively present in everyday speech—forces them to make lexical associations, i.e., learners at a higher level seem to recognize the morphological features of double particles and relate them to similar lexical items (e.g., prepositions, adverbs), inferring meaning from these connections, but do not usually produce them spontaneously in free speech.

The PI model used in the empirical section of the present study proved effective in pushing learners away from making faulty form–meaning connections and helping them develop more appropriate ones. Nevertheless, the results obtained suggest that this model could still have positive effects in “new” grammatical domains, i.e., forms or structures the learners have not previously handled in the classroom. The way the participants revealed a significant development in their interpretation of double particles shows how input processing can be beneficial in L2/L3 Learning. However, there seems to be no evidence here that it is sufficient for them to start producing the target forms in the output, at least regarding the amount of input they received in this particular study.

Despite the results of the present study, the approach and methodology used left some gaps to be filled and questions to be answered by potential future research. The open questions are related to the following points: (a) target form/structure, (b) the population under study, (c) the PI pedagogical model, (d) the reduced methodological intervention, and (e) the contrast with traditional instruction.

- (a)

- Target form/structure: with the same group of participants, would the study still have this positive outcome if not only the lexical–semantic features of the double particles were tested, but also the entire syntactic structure in which they occur? Because of their underlying grammatical deficits, the learners would be required to undergo testing for a longer time period with a more extensive set of PI sessions. This would result in a consequential analysis of other unacquired grammatical domains (e.g., verbal flection, case selection, etc.).

- (b)

- Population under study: if the population under study had a more advanced level (B2 or C1 on the CEFR scale) and fewer (or none of the) structural deficits encountered in this group, would they have more resources to correctly interpret the form and produce it more frequently? This intention could not be fulfilled in the present study, given the difficulty of finding a steady group of learners at university level with this kind of competence in German.

- (c)

- PI pedagogical model: if the target forms were “known” to the learners and had already been handled in the classroom prior to this study, would the PI model be able to determine more specific and comprehensive processing principles?

- (d)

- Reduced methodological intervention: under the circumstances of the present study or in the hypothetical scenarios mentioned in the previous open questions, what would be the conclusions of an extended experimentation and instruction period with second and third posttests to assess the long-term effects of the PI model?

- (e)

- Contrast with traditional instruction: if the present study included another group of participants who received traditional instruction on the target forms, as opposed to PI, would both methods have similar results, or would the PI model prove more effective than the traditional one? Research on this matter suggests that PI differs substantially from traditional instruction, especially between interpretation and production (Benati 2004a, 2004b; VanPatten and Cadierno 1993a, 1993b; VanPatten and Sanz 1995; VanPatten et al. 2009).

These gaps allow for more extensive and detailed future research on the acquisition of motion events with double particles, whether through VanPatten’s model or not. Since there is little to no research using PI-based methodology with respect to Portuguese and German, it would also be interesting to continue working on applying non-traditional methods to the grammatical phenomena of various languages, in order to have a fuller view of their advantages and understand to what extent they work under different circumstances, in different linguistic systems, and with learners from different language backgrounds.

Future research on these domains should, therefore, focus on: (i) continuing to study and explore motion events with double particles and trying to find a place for them in the curriculum of German as a foreign language; (ii) testing more advanced learners and a larger group of participants in the target forms; (iii) expanding the PI model to more problematic and more complex grammatical forms to see to what extent this model proves effective with more demanding structures; (iv) understanding the differences between PI and traditional instruction and the influence input has on the successful acquisition of lexical–semantic information; (v) developing new practical models for grammar instruction as a means to discover more efficient ways to teach and learn grammatical rules.

The future of pedagogy and language teaching can be heavily influenced by and benefit from cutting edge instruction models like the PI model, which aim at finding fresh and innovative ways to ease the L2-learners’ learning processes and push them towards a faster and more solid acquisition of complex linguistic domains. Grammar instruction, in particular, can profit from both input-based and output-based models of acquisition. A balance between accuracy and fluency (Richards 2001; Thornbury 1999, 2000) is also peremptory for the wholesome acquisition of a foreign language and should, therefore, be consistently present in instructional environments. Implementing these alternative tools and methods for teaching foreign languages can be troublesome, especially given the strong foundations of the more traditional approaches. Such a reformulation of the language teaching system would require both teachers and learners to be able to seize the opportunities these methods can bring along. For self-explanatory reasons, these non-traditional models should not be introduced abruptly in educational curricula, but rather by means of a transitional stage. A pilot project like this one could have countless advantages for SLA research and L2 Teaching/Learning altogether.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Cristina Flores for her diligent coordination during the realization of this study and for her insightful and constructive comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Lexical Decision Task

Figure A1.

Lexical decision task.

Appendix B. Production Tasks

Figure A2.

Pretest: Production task.

Figure A3.

Pretest: Production task.

Figure A4.

Pretest: Production task.

Figure A5.

Pretest: Production task.

Figure A6.

Pretest: Production task.

Figure A7.

Pretest: Production task.

Figure A8.

Pretest: Production task.

Figure A9.

Pretest: Production task.

Figure A10.

Pretest: Production task.

Figure A11.

Pretest: Production task.

Figure A12.

Posttest: Production task.

Appendix C. Binary-Choice Recognition Tasks

Figure A13.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A14.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A15.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A16.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A17.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A18.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A19.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A20.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A21.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A22.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A23.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A24.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A25.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A26.

Pretest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A27.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A28.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A29.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A30.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A31.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A32.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A33.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A34.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A35.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A36.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A37.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A38.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A39.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A40.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

Figure A41.

Posttest: Binary-choice recognition task.

References

- Alderson, J. Charles. 2005. Diagnosing Foreign Language Proficiency: The Interface between Learning and Assessment. London: A&C Black. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, Hans. 2011. Prüfungswissen Wortbildung. Bandar Seri Begawan: UTB, vol. 3458. [Google Scholar]

- Benati, Alessandro. 2004a. The effects of processing instruction and its components on the acquisition of gender agreement in Italian. Language Awareness 13: 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, Alessandro. 2004b. The effects of structured input activities and explicit information on the acquisition of the Italian future tense. In Processing Instruction: Theory, Research, and Commentary. Edited by Bill VanPatten. London: Routledge, pp. 207–25. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong, David, Libby M Gertken, and Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An Easy-to-Use Instrument to Assess Bilingualism. Austin: COERLL, University of Texas at Austin. Available online: https://sites.la.utexas.edu/bilingual/ (accessed on 30 September 2018).

- Cheng, An Chung. 1995. Grammar Instruction and Input Processing: The Acquisition of Spanish” ser” and” estar”. Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign County, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, An Chung. 2002. The effects of processing instruction on the acquisition of ser and estar. Hispania 85: 308–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collentine, Joseph. 1998. Processing instruction and the subjunctive. Hispania, 576–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culman, Hillah, Nicholas Henry, and Bill VanPatten. 2009. The role of explicit information in instructed SLA: an on-line study with processing instruction and german accusative case inflections. Die Unterrichtspraxis/Teaching German 42: 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, Andrew. 2004. Processing instruction and the Spanish subjunctive: is explicit information needed. In Processing Instruction: Theory, Research, and Commentary. Edited by Bill VanPatten. London: Routledge, pp. 227–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Claudia. 2008. Reexamining the role of explicit information in processing instruction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 30: 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldhahn, Dirk, Thomas Eckart, and Uwe Quasthoff. 2012. Building large monolingual dictionaries at the leipzig corpora collection: From 100 to 200 languages. LREC 29: 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Harr, Anne-Katharina. 2012. Language-Specific Factors in First Language Acquisition. The Expression of Motion Events in French and German. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw, Florencia. 2012. How effective are affective activities? Relative benefits of two types of structured input activities as part of a computer-delivered lesson on the Spanish subjunctive. Language Teaching Research 16: 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. 2004. Language typologies in our language use: The case of basque motion events in adult oral narratives. Cognitive Linguistics 15: 317–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, Emma, and Hsin-Ying Chen. 2011. The roles of structured input activities in processing instruction and the kinds of knowledge they promote. Language Learning 61: 1058–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Mercer. 1967. A Boy, a Dog, and a Frog. New York: Dial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, Mercer. 1969. Frog, Where Are You? New York: Dial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poitou, Jacques. 2003. Fortbewegungsverben, verbpartikel, adverb und zirkumposition. Cahiers d’études Germaniques 2003: 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, D. Victoria, Chun-Chieh Wang, and Hui-Huan Ann Chang. 2012. Investigating motion events in austronesian languages. Oceanic Linguistics 51: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Jack C. 2001. Accuracy and fluency revisited. In New Perspectives on Grammar Teaching in Second Language Classrooms. Edited by Eli Hinkel and Sandra Fotos. London: Routledge, pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Slobin, Dan I. 2005. Relating narrative events in translation. In Perspectives on Language and Language Development: Essays in Honor of Ruth A. Berman. Edited by Dorit Diskin Ravid and Hava Bat-Zeev Shyldkrot. Berlin: Springer, pp. 115–29. [Google Scholar]

- Talmy, Leonard. 1985. Lexicalization patterns: semantic structure in lexical forms. Language Typology and Syntactic Description 3: 36–149. [Google Scholar]

- Talmy, Leonard. 2000a. Toward a Cognitive Semantics, Vol. I: Concept Structuring Systems. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Talmy, Leonard. 2000b. Toward a Cognitive Semantics, Vol. II: Typology and Process in Concept Structuring. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thornbury, Scott. 1999. How to Teach Grammar. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Thornbury, Scott. 2000. Accuracy, fluency and complexity. Reading in Methodology 16: 139–43. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, Bill, and Cristina Sanz. 1995. From input to output: processing instruction and communicative tasks. In Second Language Acquisition Theory and Pedagogy. Edited by Fred R. Eckman, Jean Mileham, Rita Rutkowski Weber, Diane Highland and Peter W. Lee. London: Routledge, pp. 169–85. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, Bill, and Jessica Williams. 2015. Early theories in SLA. In Theories in Second Language Acquisition: An Introduction. Edited by Bill VanPatten and Jessica Williams. London: Routledge, pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, Bill, and Soile Oikkenon. 1996. Explanation versus structured input in processing instruction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 18: 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, Bill, and Stefanie Borst. 2012. The roles of explicit information and grammatical sensitivity in processing instruction: Nominative-accusative case marking and word order in german L2. Foreign Language Annals 45: 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, Bill, and Teresa Cadierno. 1993a. Explicit instruction and input processing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 15: 225–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, Bill, and Teresa Cadierno. 1993b. Input processing and second language acquisition: A role for instruction. The Modern Language Journal 77: 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, Bill, Daniela Inclezan, Hilda Salazar, and Andrew P. Farley. 2009. Processing instruction and dictogloss: A study on object pronouns and word order in Spanish. Foreign Language Annals 42: 557–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, Bill, Erin Collopy, Joseph E. Price, Stefanie Borst, and Anthony Qualin. 2013. Explicit information, grammatical sensitivity, and the first-noun principle: A cross-linguistic study in processing instruction. The Modern Language Journal 97: 506–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, Bill. 1997. The relevance of input processing to second language theory and second language teaching. In Contemporary Perspectives on the Acquisition of Spanish. Edited by Ana Teresa Pérez Leroux and William R. Glass. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, Bill. 2004. Input processing in second language acquisition. In Processing Instruction: Theory, Research, and Commentary. Edited by Bill VanPatten. London: Routledge, pp. 5–31. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, Bill. 2015. Input processing in adult SLA. In Theories in Second Language Acquisition: An Introduction. Edited by Bill VanPatten and Jessica Williams. London: Routledge, pp. 113–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Wynne. 2002. Linking form and meaning: Processing instruction. The French Review 76: 236–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Wynne. 2004. The nature of processing instruction. In Processing Instruction: Theory, Research, and Commentary. Edited by Bill VanPatten. London: Routledge, pp. 33–63. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This conflation pattern is grammatical in European Portuguese (EP), which is the variant under study, since our participants are university students in Portugal. In Brazilian Portuguese (BP) and other variants, there may be some deviation from the structure presented here, e.g., in BP, it is common to present Manner of motion by means of a gerund (flutuando, ‘floating’), while in EP the same information is typically expressed by an adverbial adjunct with a preposition (see Example 4). |

| 2 | Since the BLP was initially designed to assess language dominance of early bilinguals, some adjustments had to be made to ensure that the test would be suitable for the participants of the present study, who have, in their majority, only started learning German in the context of academic instruction. The original BLP contains an introductory section, designed to collect biographical information about the testee (name, age, sex, place of residence and highest level of formal education), and four modules related to different dimensions of language dominance (language history, language use, language proficiency, and language attitudes). Alterations were essentially made in the fourth module, since it comprised a more affective approach to the languages being assessed, normally only associated with bilinguals who carry the linguistic legacies of two separate cultures. Consequently, the module was changed from “Language Attitudes” to “Motivation and Identification with the language” and focused on gathering information about the participants’ personal connections with the assessed languages and their learning motivation. |

| 3 | This material has been widely used in the literature (e.g., Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2004; Rau et al. 2012; Slobin 2005, etc.) and has proven to be an efficient tool in that it presents several possibilities for movement description. |

| 4 | A series of Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests realized for each condition in the interpretation tasks revealed that the data were not normally distributed (p < 0.05), hence the use of non-parametric tests. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).