An Approach to Studying the Sociolinguistic Integration of Romanian Immigrants Residing in the Community of Madrid

Abstract

:1. Introduction1

1.1. Why Study the Romanian Community?

1.2. Context of the Research

1.3. Theoretical Framework

1.4. Previous Studies

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

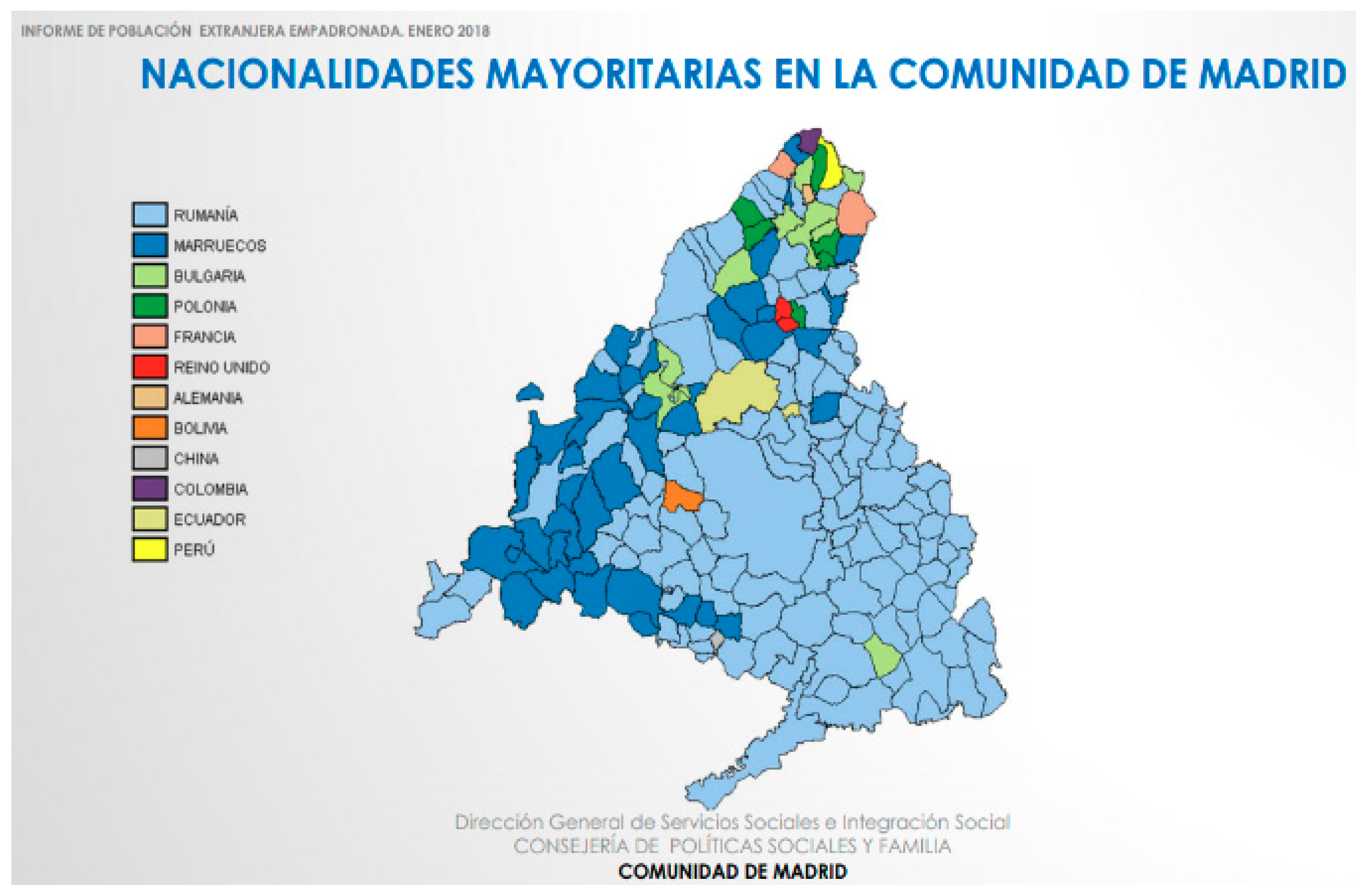

- 72 semi-structured interviews with Romanian immigrants living in different areas of Madrid (center, northwest, south, and east). The northern and western areas of Madrid had to be combined into a single area, the northwest, due to the low percentage of Romanian immigrant population living in this part of the Community of Madrid.

- 72 questionnaires on language attitudes administered to the same informants.

- Questionnaires on attitudes administered to madrileños living in Madrid.

2.2. Coding and Data Extraction

2.3. Description of the Sample

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample: Reasons for Coming to Spain and Future Expectations

3.2. Attitudes of Romanian Informants toward the Speech of Madrid

3.3. The Identity Issue

3.4. Madrileños’ View on Integration

3.5. Romanian Informants’ Self-Perception of Integration

4. Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berry, John Widdup. 2001. A Psychology of Immigration. Journal of Social Issues 57: 615–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzilă, Paul. 2016. El Rumano Hablado en España. Bucureşti: Editura Universităţii din Bucureşti. [Google Scholar]

- Cestero, Ana María, Molina Isabel, and Paredes Florentino. 2003. Metodología del Proyecto para el estudio sociolingüístico del español de España y de América. Available online: http://www.linguas.net/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=%2FthWeHX0AyY%3D&tabid=474&mid=928 (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- García Marcos, Francisco. 2015. Sociolingüística. Madrid: Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- Immigration Observatory of the Community of Madrid (Observatorio de Inmigración-Centro De estudios y Datos de la Comunidad de Madrid). 2018. Available online: http://www.comunidad.madrid/servicios/asuntos-sociales/observatorio-inmigracion-centro-estudios-datos (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Miras Páez, Elizabeth, and María Sancho Pascual. 2017. La enseñanza de ELE a niños, adolescentes e inmigrantes. In Manual del Profesor de ELE. Edited by Ana María Cestero and Inmaculada Penadés. Alcalá de Henares: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alcalá, pp. 865–912. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Fernández, Francisco. 1998. Principios de Sociolingüística y Sociología del Lenguaje. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Fernández, Francisco. 2009. Integración sociolingüística en contextos de inmigración: marco epistemológico para su estudio en España. Lengua y Migración 1: 121–56. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Fernández, Francisco. 2013. Lingüística y migraciones hispánicas. Lengua y Migración 5: 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Carrobles, Diego. 2013. Lenguas y Culturas en Contacto en Contexto Urbano: El caso de la Comunidad Rumana de Madrid. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes García, Florentino, and María Sancho Pascual. 2018. Influencia de las expectativas de permanencia o retorno en la integración sociolingüística de la población migrante en la Comunidad de Madrid. Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana 16: 41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Roesler, Patrick. 2011. Características generales del español hablado por inmigrantes rumanos en Castellón de la Plana. RedELE: Revista Electrónica de Didáctica ELE 22: 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho Pascual, María. 2013a. Integración Sociolingüística de los Inmigrantes Ecuatorianos en Madrid. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Alcalá, Alcalá de Henares, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho Pascual, María. 2013b. Introducción: lengua y migraciones en el mundo de la globalización. Lengua y Migración 5: 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz Huéscar, Gema. 2008. Actitudes lingüísticas de los inmigrantes rumanos en Alcalá de Henares. Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This paper is part of the research project’s activities “A complementary study of the sociolinguistic patterns and the processes of sociolinguistic integration in the Spanish of Madrid” (ref. FFI2015-68171-C5-4-P), financed by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain, and “The migrant population in the Autonomous Community of Madrid: interdisciplinary study and tools for sociolinguistic integration” (ref. IN.MIGRA2-CM), cofinanced by the Autonomous Community of Madrid (Spain) and the European Social Fund. |

| 2 | In this case with the madrileños. Madrileño is the demonym for Madrid natives. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez Cantador, Y. An Approach to Studying the Sociolinguistic Integration of Romanian Immigrants Residing in the Community of Madrid. Languages 2020, 5, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5010003

Pérez Cantador Y. An Approach to Studying the Sociolinguistic Integration of Romanian Immigrants Residing in the Community of Madrid. Languages. 2020; 5(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5010003

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez Cantador, Yara. 2020. "An Approach to Studying the Sociolinguistic Integration of Romanian Immigrants Residing in the Community of Madrid" Languages 5, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5010003

APA StylePérez Cantador, Y. (2020). An Approach to Studying the Sociolinguistic Integration of Romanian Immigrants Residing in the Community of Madrid. Languages, 5(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5010003