Organisational Skills in Academic Writing: A Study on Coherence and Cohesion in Pakistani Research Abstracts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Writing

1.2. Significance of the Writing ofEnglish as a Foreign/Second Language

1.3. Research Aim

- The most frequently used cohesive items in abstracts written by Pakistani research article writers;

- The functions performed by the cohesive items in the abstracts written by Pakistani research article writers; and

- The differences and similarities in the use of cohesive items in the abstracts written by Pakistani research article writers.

1.4. Research Questions

- What are the most frequently used cohesive items in abstracts written by Pakistani research article writers? This was adopted from (Alarcon and Morales 2011; Chanyoo 2018; and Liu and Braine 2005).

- What functions do the cohesive items perform in the abstracts written by Pakistani research article writers?

1.5. Significance of the Study

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cohesion and Coherence

2.2. Differences between Cohesion and Coherence

Yesterday I met an old friend in London. In London, there are numerous public libraries. These libraries were visited by boys and girls. The boys are handsome, and they often go to public swimming pools. These swimming pools were closed for several weeks last year. A week has seven days. Seven days ago, I visited my grandparents in San José …

- (1)

- It was cold in the room. Someone had opened a window.

- (2)

- There had been an accident. Two cars had crashed. Two cats died, but there were no human casualties (Brinker 2005, p. 42).

- (3)

- John took a train from Paris to Istanbul. He likes spinach (Kehler 2002, p. 2).

2.3. Pakistani ESL Writing

2.4. Academic Writing

3. Methodology

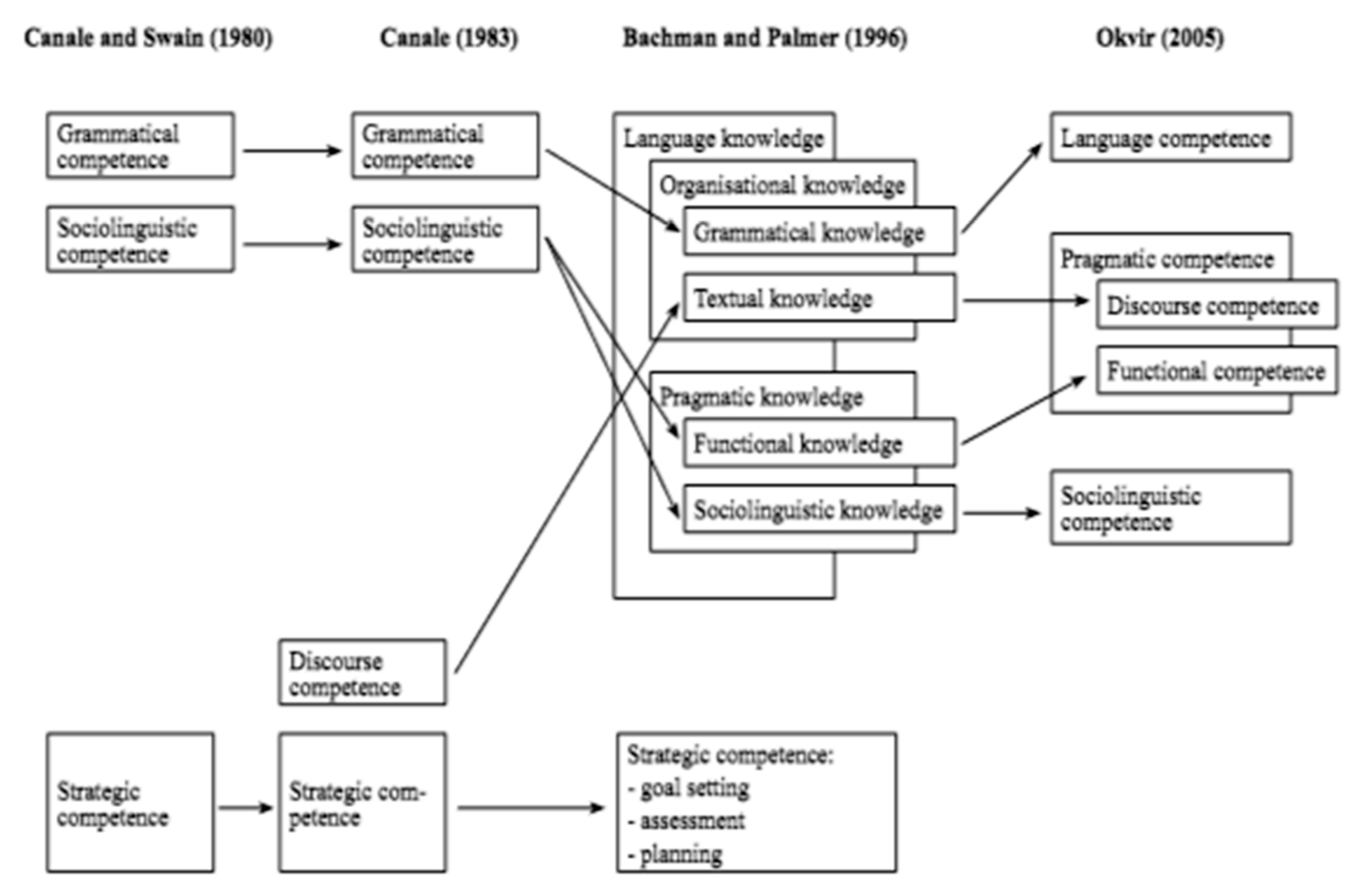

3.1. Model of the Study

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Size and Distribution of Data

3.4. Procedure for Data Collection

3.5. Source of Tagging and Analysis Tools

4. Results

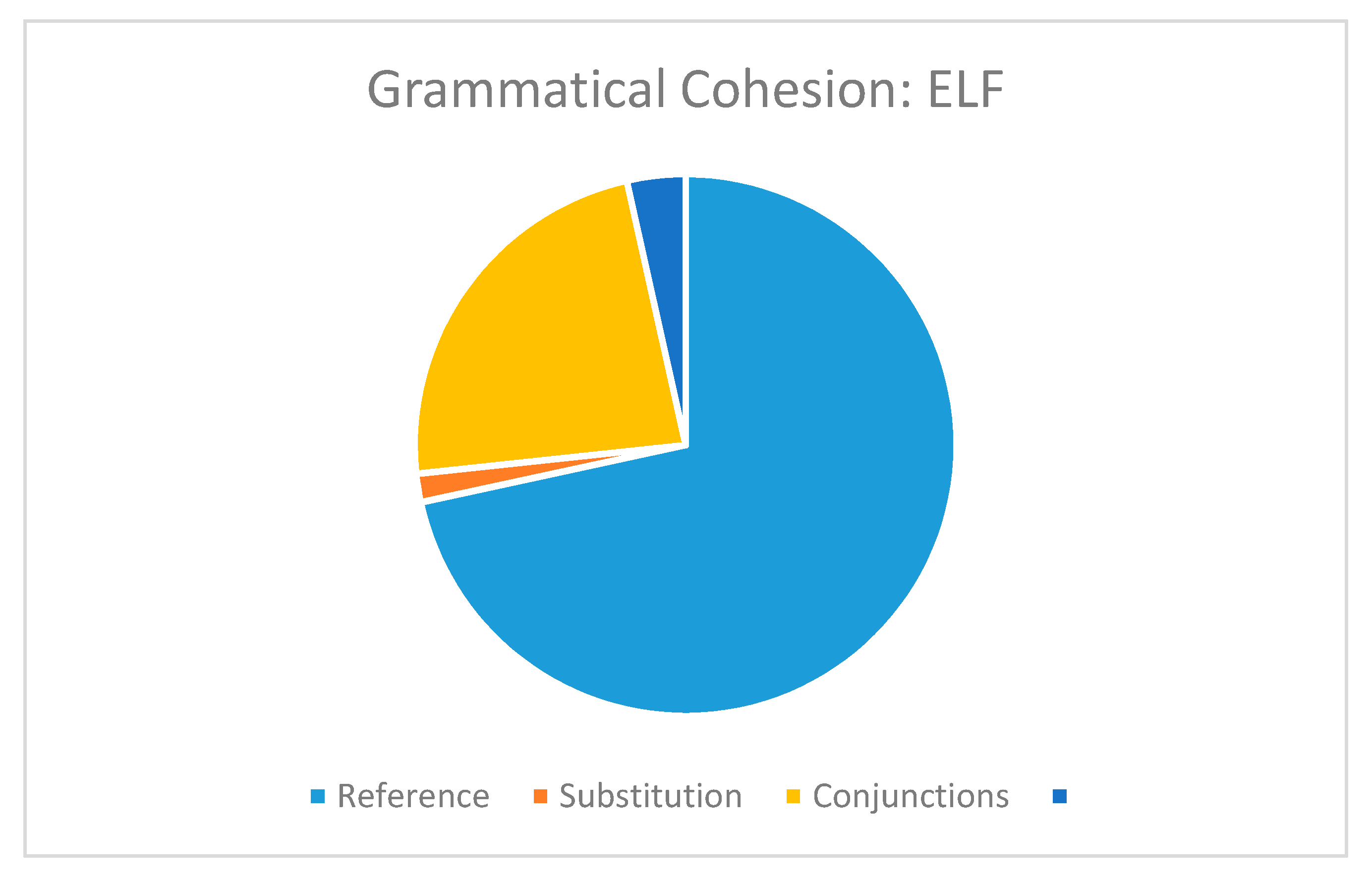

4.1. Grammatical Cohesion in ELF

4.1.1. Use of Additive Conjunctions

4.1.2. Adversative Conjunctions

4.1.3. Clausal Conjunctions

4.1.4. Temporal Conjunctions

4.1.5. Comparative Conjunctions

4.1.6. Demonstrative References

4.1.7. Existential References

4.1.8. Possessive References

4.1.9. Clausal Substitutions

4.1.10. Nominal Substitutions

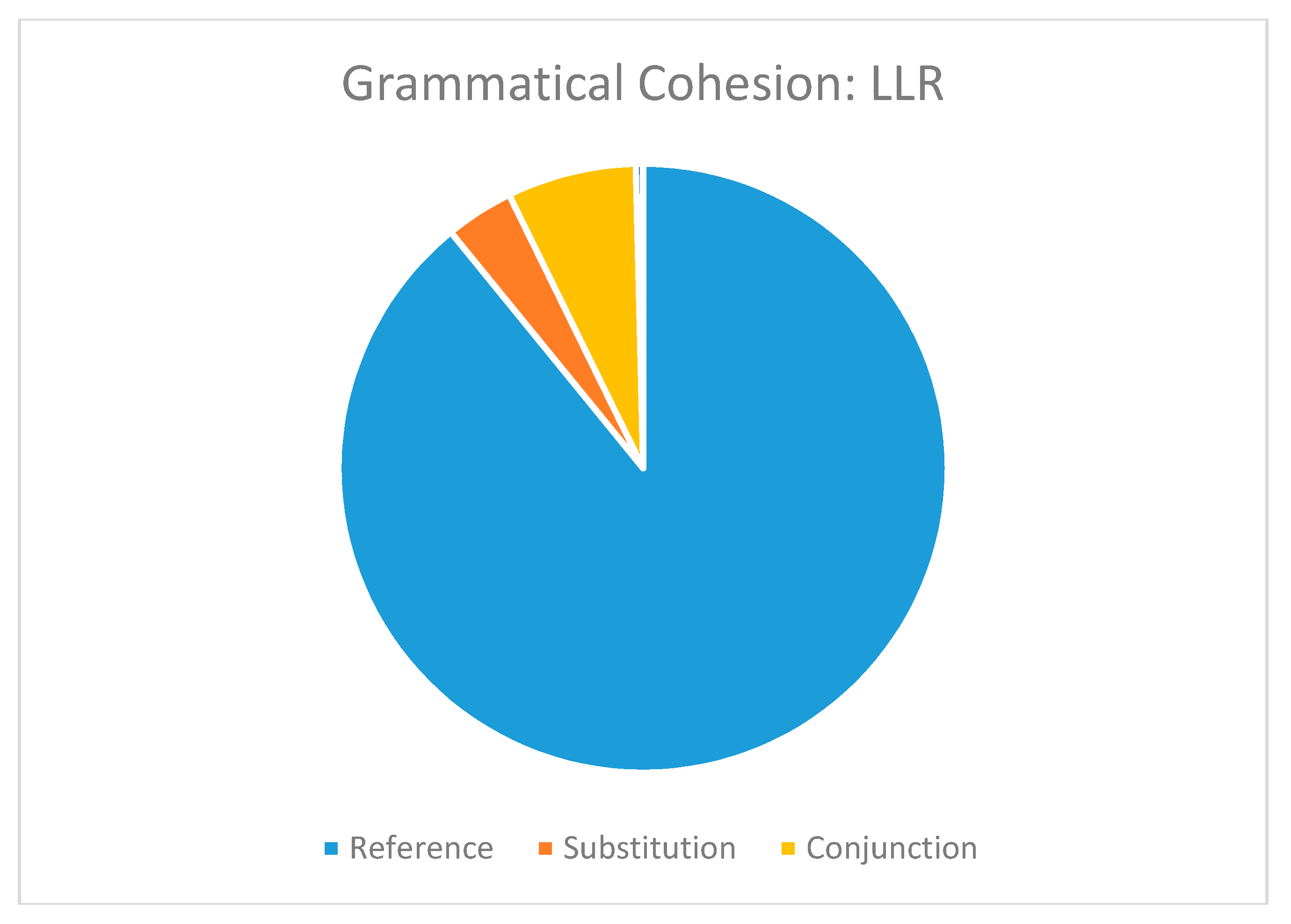

4.2. Grammatical Cohesion in the Data of the Linguistics and Literature Review Journal (LLR)

4.2.1. Additive Conjunctions

4.2.2. Adversative Conjunctions

4.2.3. Clausal Conjunctions

4.2.4. Temporal Conjunctions

4.2.5. Enumerative Lexical Connections

4.2.6. Comparative References in the Data of the Linguistics and Literature Review Journal

4.2.7. Demonstrative References

4.2.8. Personal (Existential) References

4.2.9. Personal (Possessive) References

4.2.10. Clausal Substitutions

4.2.11. Nominal Substitutions

4.3. Comparison between the Frequencies of Grammatical Cohesion in the Data of ELF and LLR

5. Discussion

- Private news channels in Pakistan, although seemingly independent and objective, reek of hidden agenda establishing their affiliations with some particular political party through their programs (Abstract_26_Personal (Possessive) Reference);

- In her novels, she makes language a means and tool to consolidate the identity of her nation through her syncretic linguistic strategy of appropriation and abrogation of English (Abstract_6_ Personal (Possessive) Reference);

- They were taught in a student-centered classroom environment (Abstract_6_Personal (Existential);

- In both these texts, the major bulk of the narrative revolves around city life—how it influences individual lives and behaviour (Abstract_11_ Demonstrative);

- Therefore, it is recommended that some modifications be made in these textbooks to improve the quality of teaching these aspects of language to L2 learners in Iranian high schools and guidance schools (Abstract_2_ Demonstrative);

- It has been observed that different conversational strategies like turn-taking, interruption and overlapping are adopted by the participants to support or challenge the state point of view (Abstract_26_Comparative);

- All such rules are added like other rules to the Urdu PCFG. An Urdu PCFG is thus obtained (Abstract_19_ Comparative).

- It has implications for all the teachers who have been teaching traditional and nontraditional adult learners in various universities of Pakistan in general (Abstract_3_Additive);

- The paper uses both medical and literary discourse to provide a functional definition of blindness, as opposed to a strictly medical definition (Abstract_7_ Additive);

- My aim is to show that language users have linguistic choices and that these choices are seldom neutral (Abstract_16_ Additive);

- It seems that, in their point of view, these pictures are harmful for the society in general, or maybe dangerous for themselves in particular (Abstract_22_ Additive);

- Moreover, from a sociocultural perspective, the status of Pakistani women will be compared with American empowered women through critical discourse analysis (Abstract_6_ Additive);

- In the same way, the data under examination indicate that complement Post Psareplaced at prehead position even though the tree is headed by English Ns, which require posthead placement of complement PPs (Abstract_11_ Adversative);

- The protagonist of the selected text cultivates a social support for herself thatis rather challenging but acts as a buffer against negative outcomes (Abstract_16_ Adversative);

- Text and language are central to Sufi literature, and therefore Sufi poets use poetic language to mesmerize the hearts of people (Abstract_13_ Clausal);

- Literary texts, written by previously colonized nations, usually highlight the major characteristics of this recurrent historical phenomenon (Abstract_2_ Temporal);

- It becomes more challenging when the teaching–learning circumstances are also difficult (Abstract_4_ Temporal).

- One group was taught through the Learner-Centered Approach, and the other was taught through the Teacher-Centered Approach (Abstract_9_Nominal);

- In the same way, the data under examination indicate that complement Post Ps are placed at a prehead position even though the tree is headed by English Ns, which require posthead placement of complement PPs (Abstract_11_ Nominal);

- In doing so, it will introduce the reader to Waseem Anwar’s critique, in the wake of postcolonial studies, of the dialogic nature of language in evaluations of race and gender (Abstract_15_ Clausal);

- Ghalib was not only an eyewitness to a great political change, but he was also a victim of it (Abstract_10_ Clausal).

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelreheim, Hussein Maghawry Hussein. 2014. A Corpus-Based Discourse Analysis of Grammatical Cohesive Devices Used in Expository Essays Written by Emirati EFL Learners at Al Ghazali School, Abu Dhabi. Ph.D. Dissertation, The British University in Dubai (BUiD), Dubai, UAE. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, Nasir, Farooq Nawaz Khan, and Nargis Munir. 2013. Factors affecting the learning of English at secondary school level in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. International Journal of English Language and Literature Studies 2: 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Muhammad, Syed Kazim Shah, and Muhammad Mushtaq. 2019. La cohesión en la escritura argumentativa: Un estudio de caso de escritores de ensayos Pakistaníes. Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores 6: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Abdel Hamid. 2010. Students’ problems with cohesion and coherence in EFL essay writing in Egypt: Different perspectives. Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal (LICEJ) 1: 211–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, Josephine B., and Katrina Ninfa S. Morales. 2011. Grammatical cohesion in students argumentative essay. International Journal of English and Literature 2: 114–27. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, Laurence. 1999. Writing research article introductions in software engineering: How accurate is a standard model? IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 42: 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, Lyle F., and Adrian S. Palmer. 1996. Language Testing in Practice: Designing and Developing Useful Language Tests. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bagarić, Vesna, and Jelena Mihaljević Djigunović. 2007. Defining communicative competence. Metodika 8: 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, Vijay Kumar. 2014. Analysing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Borger, Linda. 2014. Looking beyond Scores. A Study of Rater Orientations and Ratings of Speaking. Licentiate Thesis, Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2077/38158 (accessed on 14 November 2015).

- Brinker, Klaus. 2005. Linguistische Text Analyse. Eine Einführung in Grundbegriffe und Methoden, 6th ed. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Richard. 2017. Which Countries Have the Most English Speakers? February 17. Available online: https://k-international.com/blog/countries-with-the-most-english-speakers/ (accessed on 29 September 2019).

- Brown, Gillian, Gillian D. Brown, and Yule George. 1983. Discourse Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Canale, Michael. 1983. From communicative competence to communicative language pedagogy. In Language and Communication. Edited by Jack C. Richards and Richards W. Schmidt. London: Longman, pp. 2–27. [Google Scholar]

- Canale, Michael. 1984. A communicative approach to language proficiency assessment in a minority setting. In Communicative Competence Approaches to Language Proficiency Assessment: Research and Application. Edited by Charlene Rivera. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 107–22. [Google Scholar]

- Canale, Michael, and Merrill Swain. 1980. Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics 1: 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanyoo, Natthapong. 2018. Cohesive devices and academic writing quality of Thai undergraduate students. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 9: 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crookes, Graham. 1986. Towards a validated analysis of scientific text structure. Applied Linguistics 7: 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, Scott, and Danielle McNamara. 2010. Cohesion, coherence, and expert evaluations of writing proficiency. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society 32: 984–89. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, David. 2003. English as a Global Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, Muhammad Fareed, and Imran Khan. 2015. Writing anxiety among public and private sectors Pakistani undergraduate university students. Pakistan Journal of Gender Studies 10: 121–36. [Google Scholar]

- De Beaugrande, Robert-Alain, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 1981. Introduction to Text Linguistics. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley-Evans, Tony. 1997. Genre models for the teaching of academic writing to second language speakers: Advantages and disadvantages. In Functional Approaches to Written Text: Classroom Applications. Edited by Miller Tom. Washington, DC: United States Information Agency, pp. 150–59. [Google Scholar]

- Fareed, Muhammad, Almas Ashraf, and Muhammad Bilal. 2016. ESL learners’ writing skills: Problems, factors and suggestions. Journal of Education and Social Sciences 4: 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, Kirstin M., and John M. Swales. 1994. Competition and discourse community: Introductions from Nysvenska studier. In Text and Talk in Professional Contexts: Selected Papers from the International Conference “Discourse and the Professions”. Edited by Britt-Louise Gunnarsson, Per Linnel and Bengt Nordberg. Stockholm: ASLA, pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Steve, and Dolores Perin. 2007. Writing next-effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools. The Elementary School Journal 94: 169–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, Ghulam. 2012. An insight into difficulties faced by Pakistani student writers: Implications for teaching of writing. Journal of Educational and Social Research 2: 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1994. Spoken and written modes of meaning. In Media Texts: Authors and Readers. Edited by Graddol David and Boyd-Barrett Oliver. Clevedon, Philadelphia and Adelaide: Multilingual Matters Ltd., pp. 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood, and Ruqaiya Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Hellman, Christina. 1995. The notion of coherence in discourse. In Focus and Coherence in Discourse Processing. Edited by Rickheit Gert and Habel Christopher. Berlin and New York: de Gruyter, pp. 190–202. [Google Scholar]

- Hoey, Michael. 1991. Patterns of Lexis in Text. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huckin, Thomas. 2001. Abstracting from abstracts. In Academic Writing in Context: Implications and Applications. Edited by Hewings Martin. Birmingham: The University of Birmingham Press, pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, Ken. 2000. Disciplinary Discourses: Social Interactions in Academic Writing. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, Ken. 2003. Second Language Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Irvin, L. Lennie. 2010. What is academic writing? In Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing. Edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky. Indiana: Parlor Press, vol. 1, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kehler, Andrew. 2002. Coherence, Reference, and the Theory of Grammar. Stanford: CSLI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg, Ronald T. 2001. Long-term working memory in text production. Memory & Cognition 29: 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Chih-Hua. 1995. Cohesion and coherence in academic writing: From lexical choice to organization. RELC Journal 26: 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, Beverly, Fine Jonathan, and Young Lynne. 2005. Expository Discourse. London: A & C Black. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Meihua, and George Braine. 2005. Cohesive features in argumentative writing produced by Chinese undergraduates. System 33: 623–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makri, Anita. 2018. Pakistan and Egypt had highest rises in research output in 2018. Nature. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07841-9 (accessed on 29 September 2019). [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, Sabiha. 2005. Language Planning in Higher Education: A Case Study of Pakistan. Karachi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Melander, Bjorn, John M. Swales, and Kirstin M. Fredrickson. 1997. Journal abstracts from three academic fields in the United States and Sweden: National or disciplinary proclivities? In Intellectual Styles and Cross-Cultural Communication. Edited by Anna Duszak. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter, pp. 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Rowena. 2013. Writing for Academic Journals. Berkshire: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, Raymond S., David N. Perkins, and Edward E. Smith. 2014. The Teaching of Thinking. London and New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oshima, Alice, and Ann Hogue. 2007. Introduction to Academic Writing. New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Pinon, Robert, and John Haydon. 2010. English Language Quantitative Indicators: Cameroon, Nigeria, Rwanda, Bangladesh and Pakistan. A Custom Report Compiled by Euromonitor International for the British Council. London: Euromonitor International Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, Ambika Prasad. 2018. Academic Writing: Coherence and Cohesion in Paragraph (Research Project). Dhankut M. Campus, Dhankuta, Nepal. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322537095_Academic_Writing_Coherence_and_Cohesion_in_Paragraph (accessed on 3 November 2019).

- Rao, Zhenhui. 2007. Training in brainstorming and developing writing skills. ELT Journal 61: 100–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Jack, John Platt, and Heidi Weber. 1985. Longman Dictionary of Applied Linguistics. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Samraj, Betty. 2005. An exploration of a genre set: Research article abstracts and introductions in two disciplines. English for Specific Purposes 24: 141–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savignon, Sandra J. 1972. Communicative Competence: An Experiment in Foreign Language Teaching. Philadelphia: The Centre for Curriculum Development Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, Shahid. 2007. Rethinking Education in Pakistan: Perceptions, Practices and Possibilities. Karachi: Paramount Publishing Enterprise. [Google Scholar]

- Swales, John M. 1990. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swales, John M., and Christine B. Feak. 2012. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Tasks and Skills. Michigan: Michigan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swales, John M., and Hazem Najjar. 1987. The writing of research article introductions. Written Communication 4: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanskanen, Sanna-Kaisa. 2006. Collaborating towards Coherence: Lexical Cohesion in English Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, vol. 146. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Geoff. 1996. Introducing Functional Grammar, 2nd ed. London: Hodder Education. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, Richard Watson, Somreudee Khongput, and Pornapit Darasawang. 2007. Coherence, cohesion and comments on students’ academic essays. Assessing Writing 12: 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutanova Kristina, Dan Klein, Christopher D. Manning, and Yoram Singer. 2003. Feature-rich part-of-speech tagging with a cyclic dependency network. In Proceedings of the 2003 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics on Human Language Technology-Volume 1. Stroudsburg: Association for computational Linguistics, pp. 173–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tsareva, Anastasia. 2010. Grammatical cohesion in argumentative essays by Norwegean and Russian learners. Master’s Thesis, The University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

| Categories of Cohesion | Lexical Categories | (a) | Repetition | |

| Synonyms | ||||

| Superordinate | ||||

| General words | ||||

| (b) | Collocation | |||

| Grammatical Categories | (a) | Exophoric reference (situational) | ||

| Endophoric reference (textual) | Cataphoric (follows in the text) | |||

| Anaphoric (preceded in the text) | ||||

| (b) | Conjunctions | |||

| (c) | Ellipses | |||

| (d) | Substitutions | |||

| Grammatical Cohesion | Reference | Possessive | Mine or my; yours or your; ours or our; his, hers or her; its, theirs, their, its and one’s |

| Existential | I/me, you, we/us, he/him, she/her, it, one and they/them | ||

| Demonstratives | This or that, here or there, these or those and definite articles(the) | ||

| Comparatives | Other, same, so many, identical, else, more, similar, such, different, similarly, better | ||

| Substitution | Nominal | one, ones, same | |

| Verbal | |||

| Clausal | so, not | ||

| Conjunctions | Additive | And, or, nor, and also, furthermore, or else, likewise, in other words, by the way, for example, thus, in addition, besides, that is, moreover, likewise, similarly, in the same way, in contrast, alternatively, on the other hand | |

| Adversatives | Yet, but, though, instead, only, at last, at any rate, rather, anyhow, in fact, on the contrary, in any case, I mean, although, despite this, nevertheless, on the other hand, however | ||

| Clausal | Consequently, then, therefore, because, otherwise, it follows, apart from this, hence, on this basis, for this reason, so, to this end | ||

| Temporal | After, an hour later, at once, at the same time, at last, at this moment, before, before that, during, finally, first, formerly, in conclusion, next, next day, meanwhile, previously, second, soon, to sum up, then, third, up to now, when | ||

| Name of Journal | Abstract |

|---|---|

| Linguistics and Literature Review (LLR) | 25 |

| ELF Annual Research Journal (ELF) | 25 |

| Total | 50 |

| Grammatical Cohesion | Occurrences | |

|---|---|---|

| References | Personal (possessive) | 49 |

| Personal (existential) | 63 | |

| Demonstratives | 540 | |

| Comparatives | 24 | |

| Total | 676 | |

| Substitution | Nominal | 4 |

| Verbal | 0 | |

| Clausal | 12 | |

| Total | 16 | |

| Conjunctions | Additive | 174 |

| Adversative | 15 | |

| Clausal | 8 | |

| Temporal | 22 | |

| TOTAL | 219 | |

| Grand Total | 911 | |

| Sr. No. | Conjunction | Additive | Frequency |

| 1 | and | 161 | |

| 2 | or | 9 | |

| 3 | besides | 1 | |

| 4 | moreover | 1 | |

| 5 | and also | 1 | |

| 6 | in other words | 1 | |

| Total | 174 | ||

| Sr. No. | Conjunction | Adversative | Frequency |

| 1 | but | 10 | |

| 2 | only | 3 | |

| 3 | although | 1 | |

| 4 | though | 1 | |

| Total | 15 | ||

| Sr. No. | Conjunction | Clausal | Frequency |

| 1 | therefore | 3 | |

| 2 | so | 2 | |

| 3 | hence | 1 | |

| 4 | then | 1 | |

| 5 | it follows | 1 | |

| Total | 8 | ||

| Sr. No. | Conjunction | Temporal | Frequency |

| 1 | first | 6 | |

| 2 | second | 5 | |

| 3 | when | 3 | |

| 4 | finally | 2 | |

| 5 | next | 2 | |

| 6 | after | 1 | |

| 7 | previously | 1 | |

| 8 | then | 1 | |

| 9 | at the same time | 1 | |

| Total | 22 | ||

| Sr. No. | References | Comparatives | Frequency |

| 1 | different | 7 | |

| 2 | other | 7 | |

| 3 | such | 6 | |

| 4 | better | 2 | |

| 5 | same | 1 | |

| 6 | similar | 1 | |

| Total | 24 | ||

| Sr. No. | References | Demonstrative | Frequency |

| 1 | the | 437 | |

| 2 | that | 47 | |

| 3 | this | 38 | |

| 4 | these | 9 | |

| 5 | there | 5 | |

| 6 | those | 3 | |

| 7 | here | 1 | |

| Total | 540 | ||

| Sr. No. | References | Personal (Existential) | Frequency |

| 1 | it | 22 | |

| 2 | they | 11 | |

| 3 | her | 9 | |

| 4 | we | 6 | |

| 5 | them | 4 | |

| 6 | I | 3 | |

| 7 | one | 3 | |

| 8 | us | 3 | |

| 9 | him | 1 | |

| 10 | you | 1 | |

| Total | 63 | ||

| Sr. No. | References | Personal (Possessive) | Frequency |

| 1 | their | 31 | |

| 2 | her | 9 | |

| 3 | its | 7 | |

| 4 | his | 1 | |

| 5 | my | 1 | |

| Total | 49 | ||

| Sr. No. | Substitution | Clausal | Frequency |

| 1 | not | 10 | |

| 2 | so | 2 | |

| Total | 12 | ||

| Sr. No. | Substitution | Nominal | Frequency |

| 1 | one | 3 | |

| 2 | Same | 1 | |

| Total | 4 | ||

| Grammatical Cohesion | Occurrences | |

|---|---|---|

| References | Personal (possessive) | 55 |

| Personal (existential) | 57 | |

| Demonstratives | 331 | |

| Comparatives | 24 | |

| Total | 467 | |

| Substitution | Nominal | 15 |

| Verbal | 0 | |

| Clausal | 4 | |

| Total | 19 | |

| Conjunctions | Additive | 7 |

| Adversative | 13 | |

| Clausal | 6 | |

| Temporal | 10 | |

| Total | 36 | |

| Total | 522 | |

| Sr. No. | Conjunction | Additive | Frequency |

| 1 | not | 2 | |

| 2 | so | 2 | |

| 3 | in addition | 1 | |

| 4 | that is | 1 | |

| 5 | in the same way | 1 | |

| Total | 7 | ||

| Sr. No. | Conjunction | Adversative | Frequency |

| 1 | although | 3 | |

| 2 | but | 3 | |

| 3 | however | 3 | |

| 4 | instead | 1 | |

| 5 | only | 1 | |

| 6 | rather | 1 | |

| 7 | though | 1 | |

| Total | 13 | ||

| Sr. No. | Conjunction | Clausal | Frequency |

| 1 | So | 2 | |

| 2 | Then | 2 | |

| 3 | hence | 1 | |

| 4 | therefore | 1 | |

| Total | 6 | ||

| Sr. No. | Conjunction | Temporal | Frequency |

| 1 | when | 3 | |

| 2 | first | 2 | |

| 3 | then | 2 | |

| 4 | after | 1 | |

| 5 | during | 1 | |

| 6 | finally | 1 | |

| Total | 10 | ||

| Sr. No. | Logical Connections | Enumerative | Frequency |

| 1 | First | 2 | |

| Total | 2 | ||

| Sr. No. | References | Comparatives | Frequency |

| 1 | same | 8 | |

| 2 | other | 7 | |

| 3 | different | 4 | |

| 4 | such | 4 | |

| 5 | better | 1 | |

| Total | 24 | ||

| Sr. No. | References | Demonstrative | Frequency |

| 1 | the | 270 | |

| 2 | this | 32 | |

| 3 | that | 20 | |

| 4 | these | 5 | |

| 5 | there | 4 | |

| Total | 331 | ||

| Sr. No. | References | Personal (Existential) | Frequency |

| 1 | it | 15 | |

| 2 | her | 8 | |

| 3 | them | 8 | |

| 4 | they | 8 | |

| 5 | one | 7 | |

| 6 | i | 5 | |

| 7 | she | 5 | |

| 8 | we | 1 | |

| Total | 57 | ||

| Sr. No. | References | Personal (Possessive) | Frequency |

| 1 | their | 29 | |

| 2 | its | 10 | |

| 3 | her | 8 | |

| 4 | my | 4 | |

| 5 | his | 3 | |

| 6 | our | 1 | |

| Total | 55 | ||

| Sr. No. | Substitution | Clausal | Frequency |

| 1 | not | 2 | |

| 2 | so | 2 | |

| Total | 4 | ||

| Sr. No. | Substitution | Nominal | Frequency |

| 1 | same | 8 | |

| 2 | one | 7 | |

| Total | 15 | ||

| Grammatical Cohesion | Occurrences in the ELF Annual Research Journal | Occurrences in the Linguistics and Literature Review Journal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| References | Personal (possessive) | 49 | 55 |

| Personal (existential) | 63 | 57 | |

| Demonstratives | 540 | 331 | |

| Comparatives | 24 | 24 | |

| Total | 676 | 467 | |

| Substitution | Nominal | 4 | 15 |

| Verbal | 0 | 0 | |

| Clausal | 12 | 4 | |

| Total | 16 | 19 | |

| Conjunctions | Additive | 174 | 7 |

| Adversative | 15 | 13 | |

| Clausal | 8 | 6 | |

| Temporal | 22 | 10 | |

| Total | 219 | 36 | |

| Grand Total | 911 | 522 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmad, M.; Mahmood, M.A.; Siddique, A.R. Organisational Skills in Academic Writing: A Study on Coherence and Cohesion in Pakistani Research Abstracts. Languages 2019, 4, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040092

Ahmad M, Mahmood MA, Siddique AR. Organisational Skills in Academic Writing: A Study on Coherence and Cohesion in Pakistani Research Abstracts. Languages. 2019; 4(4):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040092

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmad, Muhammad, Muhammad Asim Mahmood, and Ali Raza Siddique. 2019. "Organisational Skills in Academic Writing: A Study on Coherence and Cohesion in Pakistani Research Abstracts" Languages 4, no. 4: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040092

APA StyleAhmad, M., Mahmood, M. A., & Siddique, A. R. (2019). Organisational Skills in Academic Writing: A Study on Coherence and Cohesion in Pakistani Research Abstracts. Languages, 4(4), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040092