Abstract

The development of oral comprehension skills is rarely studied in second and foreign language teaching, let alone in learning contexts involving students with limited or interrupted formal education (SLIFE). Thus, we conducted a mixed-methods study attempting to measure the effect of implicit teaching of oral comprehension strategies with 37 SLIFE in Quebec City, a predominantly French-speaking city in Canada. Two experimental groups received implicit training in listening strategies, whereas a control group viewed the same documents without strategy training. Participants’ listening comprehension performance was measured quantitatively before the treatment, immediately after, and one week later with three different versions of an oral comprehension test targeting both explicit and implicit content of authentic audiovisual documents. Overall, data analysis showed a low success rate for all participants in the oral comprehension tests, with no significant effect of the experimental treatment. However, data from the intervention sessions revealed that the participants’ verbalisations of their comprehension varied qualitatively over time. The combination of these results is discussed in light of previous findings on low literate adults’ informal and formal language learning experiences.

1. Introduction

Instructed second language acquisition (ISLA) research is typically conducted in Western societies and focuses largely on educated, highly literate, middle-class language learners (Ortega 2019). In fact, very few ISLA studies have been carried out with students with limited or interrupted formal education (SLIFE), even though Bigelow and Tarone (2004) have long called for a more systematic integration of this population so as to better understand the impact of first language (L1) literacy skills on formal acquisition of additional languages (Lx) (see also, Young-Scholten 2013), and even though amount and types of literacy experiences occupy an important place in Hulstijn’s (2019) individual differences framework of Lx learning. Of the limited classroom studies conducted with SLIFE (e.g., Strube et al. 2013), none, to our knowledge, focus on the teaching and learning of listening skills; however, listening skills are prevalent and relevant for successful social interactions (Wolvin 2018) as well as for the development of other language skills (Vandergrift 2008), such as literacy development (Strube et al. 2013). This lack of attention to the development of listening skills is not entirely surprising since classroom-based research on Lx listening instruction is, to date, relatively scarce (Vandergrift and Cross 2017).

Learning to listen in an Lx is difficult due to the complex orchestration of the many processes involved (Graham 2017). When engaged in the listening process, listeners must skilfully and simultaneously process the linguistic, pragmatic, semantic, contextual and background information communicated, explicitly or implicitly, in the message (Rost 2011). Listening in an Lx is all the more challenging because of the ephemeral nature of spoken language. Indeed, the listener does not have the option of reviewing all the information present in the input and has little control over the rate of speech and comprehensibility of their interlocutor (Vandergrift 2006). When successful processing of all these elements is not impeded, a coherent representation of the message is formed and comprehension may occur (Wolvin 2018).

According to Graham and Macaro (2008, p. 750), the following set of listening strategies (i.e., conscious plans to manage incoming speech (Rost 2011)) are generally associated with successful listening outcomes: (1) making predictions about the likely content of a passage; (2) selectively attending to certain aspects of the passage (i.e., deciding to “listen out for” particular words or phrases or idea units); (3) monitoring and evaluating comprehension (i.e., checking that one is in fact understanding or has made the correct interpretation); and (4) using a variety of clues (linguistic, contextual and background knowledge) to infer the meaning of unknown words. There is evidence to suggest that more successful Lx listeners naturally deploy these listening strategies when faced with a listening task, while less skilled Lx listeners do not, unless they are explicitly (Cross 2010; Diaz 2015; Graham et al. 2008; Seo 2005) or implicitly trained to do so (Tafaghodtari and Vandergrift 2008; Vandergrift and Tafaghodtari 2010). Although these classroom interventions differed in terms of number and type of listening strategies (explicitly or implicitly) taught to Lx listeners, they all used elements of metacognition: development of the ability to recognise the mental processes involved in listening comprehension, the ability to examine the (social, cognitive and affective) factors that impede, slow down or facilitate listening, the ability to identify what contributes or hinders sound or word perception, or the ability to choose strategies that foster overall listening development and comprehension (see Vandergrift and Goh 2012). In other words, these interventions all aimed at enabling learners to take ownership of the listening process.

Despite the growing popularity of teaching listening strategies and metacognition to facilitate and maximise listening comprehension, Lx learners generally face challenges when it comes to regulating their listening behaviours (Vandergrift and Goh 2012). Even when they have access to a significant number of strategies, they still struggle to use them effectively, to alternate between them when needed, to review their interpretations when problems occur, and to use their strategies in naturalistic settings (Vandergrift and Goh 2012). Although these findings emerged from studies carried out with literate Lx learners, we can assume that the same findings may well apply to SLIFE as these learners are not used to reflecting on their actions and thoughts regarding how they learn (DeCapua and Marshall 2015).

In addition, because of the effects of schooling and/or literacy on cognitive function and organisation (Huettig and Mishra 2014), SLIFE, who are taking their first steps into literacy education, often cannot reach an abstraction level allowing them to think about language as an object of analysis (Bigelow and Vinogradov 2011). In addition, since they struggle to engage in learning activities that do not reflect their life experiences or needs (Huettig and Mishra 2014), the use of explicit strategy training (e.g., explicit teaching about how to monitor and review their interpretations of the message, naming abstract concepts of cognition and linguistic forms) appeared unsuitable for this population. Hence, we decided to carry out a partial replication of the implicit intervention designed by Vandergrift and Tafaghodtari (2010), which focuses on awareness of the listening process (i.e., the intervention encouraged learners to formulate and validate their hypotheses, to identify and solve the listening problems they encountered, and to formulate goals for future listening tasks, without explicitly teaching them to systematically follow these steps). Indeed, the possibility of learning implicitly while listening, as opposed to being explicitly told how and when to deploy their attentional and processing resources, seemed better suited for SLIFE not only because they thrive in experiential, contextually-embedded learning rather than in formal, decontextualised learning (Keller 2017; Moore 1999), but also because this type of intervention of yielded significant listening gains for less-skilled listeners, but not for more-skilled listeners in Vandergrift and Tafaghodtari’s (2010) study.

The present study thus sought to fill an important gap in the literature by examining the effects of an implicit listening strategies training, adapted from Vandergrift and Tafaghodtari (2010), on the listening comprehension skills of SLIFE. In particular, this small-scale study addressed the following research question: Does implicit teaching of listening strategies and metacognition help foster oral comprehension of adults with low levels of education who are learning French Lx?

2. Materials and Methods

To respond to the research question, we used a mixed-method approach. Quantitative data were collected through listening comprehension tests used in pretest–posttest design. Qualitative data were obtained through experimental group participants’ verbalisations during the first and last training sessions.

2.1. Participants

The current study used a convenience sample of 37 low literacy adult immigrants (19 females and 18 males) learning French in an adult education centre located in Quebec City, Canada1. Participants ranged in age from 16 to 77 and were Nepali or Arabic speakers. The majority of the participants immigrated to Canada an average of 1.5 years prior to the study, and few individuals immigrated less than a year or up to five years before2. Participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study. The experimental group was composed of two intact groups (Groups A and B, n = 25) and the control group of one intact group (Group C, n = 12). All three groups had different teachers and were of comparable levels, according to the centre’s placement test and home program, although Group A (n = 13) was slightly weaker in terms of literacy skills (level 2) than Group B (n = 12) and Group C (both at level 3)3. All participants were identified by a code referring to their group (A, B or C) and a random number from 01 to 15. In each group, some individuals declined our invitation to participate in the study (n = 4) or had hearing problems preventing them from participating (n = 1). Partial results are included for one participant who agreed to participate but withdrew after two training sessions. The qualitative results presented are drawn from the 17 participants from the experimental group (n = 25) who took part in all five intervention sessions, while the quantitative results are calculated from all the participants (n = 37).

2.2. Intervention

2.2.1. Video Material

The intervention consisted of five weekly training sessions involving the first author and two participants. The material was planned around video blog (henceforth vlog) excerpts, lasting between 60 and 90 s, recorded by famous French-Canadian YouTubers4. The decision to use this genre was based on two elements. First, we wanted to use video materials that portrayed authentic day-to-day language use of the target French variety (i.e., Canadian French, not modified to facilitate the learning of Lx), so as to expose learners to language and cultural content they would most likely hear outside the classroom. Second, with vlogs, viewers are exposed to an almost uninterrupted flow of speech in the Lx, have no written reference and cannot easily use visual cues to infer meaning. In other words, vlogs, unlike other types of staged or scripted video materials, provide ideal conditions to observe how participants process naturalistic linguistic input.

The five vlogs used for the intervention were selected because the vloggers discussed themes relevant to the regular classroom activities underway during data collection: housing, personal life, and health. The participants’ teachers confirmed the relevance of these specific vlog excerpts for their learners.

2.2.2. Procedure

Vandergrift and Tafaghodtari’s (2010) original intervention consisted of twelve in-class listening sessions. During each listening session, the participants were asked to engage in a three-step listening strategy sequence. After the first listening task, each participant individually filled out a free-recall listening journal, in which they wrote their hypotheses and how accurate these were, the problems encountered while listening and how they overcame them. After the second listening task, participants worked in pairs to add missing information to their listening journal. After the third listening task, participants discussed their strategies with the whole class and then completed the last part of their journal, which required them to set goals for the next listening session. The researchers then reviewed their listening journals and gave them feedback on their strategy use, always implicitly. At no point were the strategies explicitly taught.

Given time constraints, our partial replication of Vandergrift and Tafaghodtari’s (2010) intervention consisted of five listening training sessions. The original three-step sequence, consisting of individual, dyadic and whole-class activities, was replicated. However, the current four-step intervention had one major change with the original study, as it was adapted to eliminate the use of print or writing. Thus, the required journal entries from the original study were replaced with discussions about the listening experience with the first author—first individually, then in dyads, and then individually again—and a fourth step in which the regular teacher modelled the same task with the first author.

Two students (and a group of three for Group A’s third intervention session) at a time from each experimental group were taken to a different room to receive the implicit strategy training. For the first viewing of the vlog which lasted between 60 and 90 s, one participant remained in the room with the first author, while the other one waited outside. The participant was asked what he/she understood about the excerpt and was prompted to elaborate as much as he/she could. Oral feedback on listening strategies was then implicitly provided to the participant (e.g., “Est-ce qu’on a besoin de comprendre tous les mots?”; “Do you really need to understand every single word?” (addressed to B09)). Then, this participant stepped out of the room while his/her peer watched the same vlog excerpt with the first author, who repeated the procedure, ending with the grouping of both participants. After the second viewing, this time in dyads, participants were asked to talk to one another, in the language of their choice, about what they had understood and to discuss their listening experience. The students then viewed the excerpt one last time individually and were asked what they had understood and about their overall listening experience, while their peer waited in an adjacent room. They returned to their classroom and two other participants accompanied the first author. The whole-class activity took place one or two days after the initial viewing of the excerpt and involved the regular teacher (one for each group) and first author modelling the expected task5 using the same excerpt that was used during the previous intervention session. The teacher modelled various listening strategies such as selective attention, inferencing on what is not understood and monitoring those inferences while the students were required to “help” their teacher after the second viewing of the excerpt: they directed her attention on elements they found striking, asked her questions, shared their hypotheses and related personal experiences and, most of the time, recalled what they understood all at the same time. Each intervention lasted between 10 and 20 min with each pair of participants, and 15 min in class. The control group watched the same vlog excerpts twice, as a whole-class activity, but they did not receive any listening strategies training or feedback from their regular teacher. The vlog excerpts were used as a way to introduce a new theme discussed in class.

2.3. Instruments

Data were collected using two different instruments designed to measure listening comprehension performance. First, quantitative data were gathered using listening comprehension tests adapted to meet SLIFE’s characteristics (Section 2.3.1). Qualitative data were also collected during the intervention to allow for a finer-grained analysis of participants’ listening comprehension performance (Section 2.3.2).

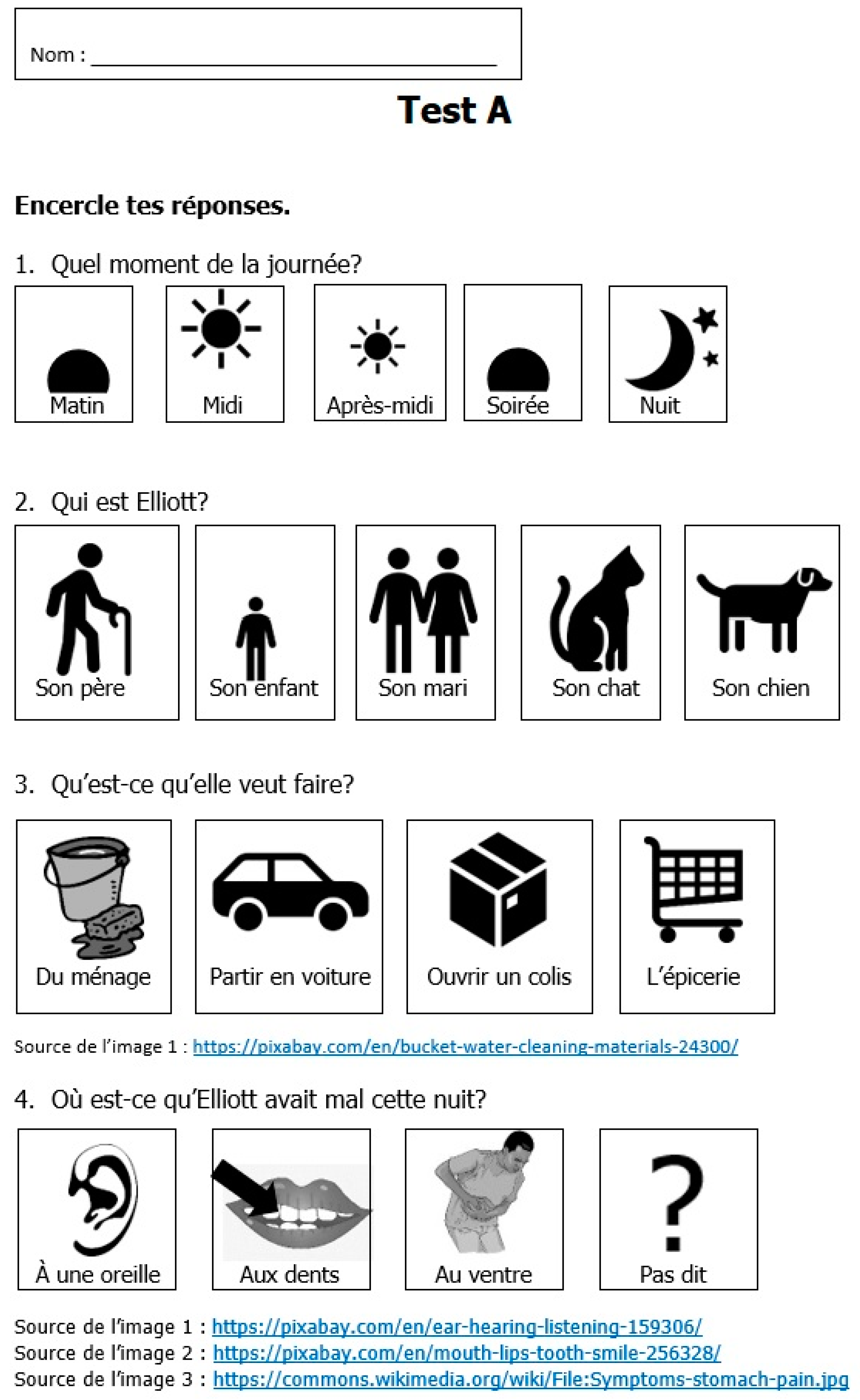

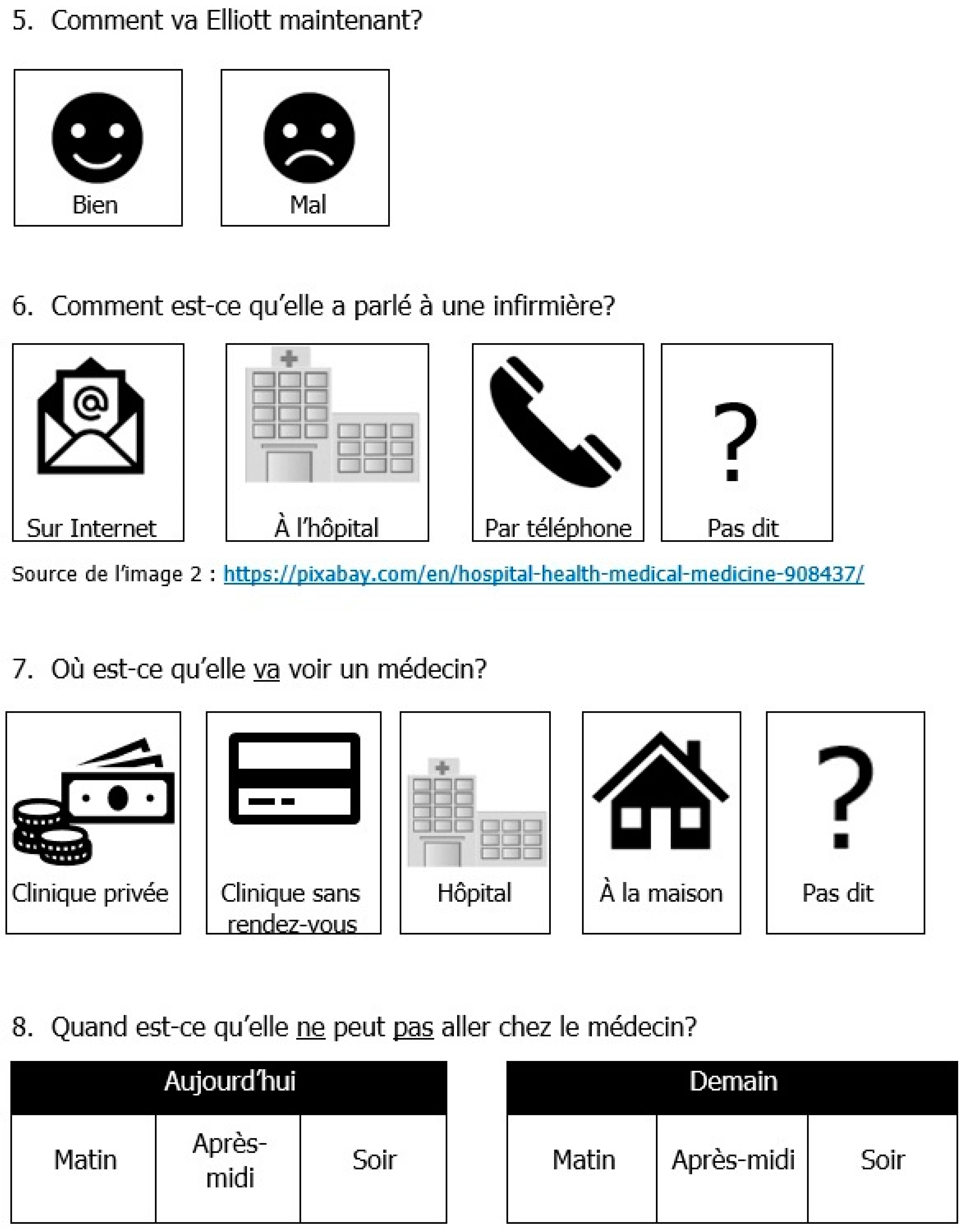

2.3.1. Quantitative Test Design, Data Collection Procedures and Coding

To measure listening comprehension performance quantitatively, we designed three listening comprehension tests to assess participants’ listening comprehension pre- and post-treatment, as, to our knowledge, no standardised test measuring SLIFE’s listening skills in French Lx exists. The three tests (see Appendix A for an example) consisted of eight multiple-choice questions about the content of a 1-min vlog excerpt, similar to those used for the intervention sessions. To ensure construct validity of the instruments, items had different levels of difficulty, following Brown’s (1995) criteria. The test items targeted information that was either explicitly or implicitly stated in the excerpt, the former being easier than the latter. Each test differed slightly in terms of type of information targeted in the questions; the majority of the items on all of the three tests addressed explicitly stated elements in the vlog (M = 5.66 questions) and the remaining questions (M = 2.34) targeted implicit addressed elements. A first version of the test was piloted with 17 participants sharing the same characteristics as our participants before designing the final three versions of the test.

Precautions were taken to minimise the impact of print on participants’ listening comprehension performance (Kosmidis et al. 2011). First, according to the teachers whose students agreed to participate in the study, all questions were formulated in a short, simple and unambiguous manner (Mackey and Gass 2016). Second, all the answer choices used the same layout (i.e., a pictogram accompanied by a word or a multi-word unit written at the bottom of a box) and required no written production from the participants. Third, as per Condelli et al.’s (2009) recommendation to avoid indirectly questioning participants about their cultural knowledge, we also asked the participating teachers to review our questions and answer choices to ensure they were easily comprehensible by the learners. Last, all the questions, as well as the answer choices, were read after each of the three viewings of the vlog excerpt to make sure that the difficulty of reading the questions did not interfere with the measurement of listening performance (Bigelow et al. 2006).

To ensure internal validity of our instruments and to avoid training effects, each of the three tests (A, B, C) were used with a subset of participants in each group in the pretest, before the intervention (T1), in the immediate posttest (T2) and in the delayed posttest (T3, one week after the end of the treatment) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Counterbalancing procedure.

2.3.2. Qualitative Data Collection Procedures and Coding

To measure listening comprehension performance qualitatively, each step of the strategies training sessions was recorded for all participants, resulting in two individual and one shared recordings for each session of each participant. Training sessions 1 and 5 were analysed for the participants (n = 17) who took part in all five intervention sessions (thus excluding eight participants who missed at least one session) using a coding scheme adapted from Kim (1995) (see Appendix C for our adaptation of the scale). Similar to Kim (1995), each descriptor included two dimensions. The first one was related to sophistication of the connections between words and/or phrases; this dimension corresponded to a score ranging from 1 (isolated words as if reciting a list) to 4 (connected phrases in the form of a [partial] narration). The second dimension referred to the degree to which elements identified by the participant were actually related to the vlog content (“+” for relevant information, and “−” for irrelevant information). Eight scores were thus possible (1+, 1−, 2+, 2−, etc.).

Coding data from SLIFE free recall production posed some challenges in terms of interpretation of their communicative intentions. While ISLA researchers typically rely on morphological or lexical cues to gain access to the participants’ depth of language processing, we could not replicate this research convention due to our participants’ limited oral production skills. Instead, we had to rely on phonological cues present in the verbalisation to infer whether they were reciting the words and phrases they thought they had understood (scores 1 and 2) or whether they were attempting to establish connections between different elements of the excerpt (scores 3 and 4). For example, falling intonation or silent pauses between elements were interpreted as marking a simple account of the words or phrases decoded from the excerpt, whereas output produced without falling intonation or hesitation were interpreted as a manifestation of attempted connection between words or phrases. The score was assigned based on the listening performance after the third viewing at Time 1 and 5. When the coding scheme was finalised, a subsample of the data was verified independently by the two coauthors to ensure that the categories were clearly distinguishable.

3. Results

3.1. Listening Performance on the Quantitative Measure: Pre, Post and Delayed Tests Scores

To answer our research question, we attributed one point for each correct answer on the test (maximum possible score = 8). We then calculated the mean scores (and standard deviations) on the pretest, posttest and delayed posttest for both the experimental groups and the control group, that we present in the form of success rate (in %) in Table 2. The results show that the three groups of participants were not comparable at the beginning of the intervention and that their listening performance evolved differently over time. It appears that the trajectories of the three groups are very different, regardless of whether they had participated in an implicit listening strategies training intervention or not. Data obtained from the listening tests thus show that participants in the experimental groups did not make long-term gains in listening performance as a result of the intervention.

Table 2.

Mean (and standard deviation) on the listening comprehension tests (in %).

After ensuring that assumptions of homoscedasticity and normal distribution of variance were met, we conducted a four-factor repeated measures ANOVA (group of participants, sequence, time and tests). The test results indicate an overall effect of the group (F (2, 23.2) = 14.55, p < 0.0001), however, no effect for sequence, time or test were found. This indicates that there was a significant difference in the three groups’ performance on the tests regardless of sequence, time, or test.

Further descriptive analyses were conducted to determine whether participants’ listening performance differed between items that were explicitly (easier) or implicitly (more difficult) stated in the vlog excerpt. Table 3 reveals once again that the groups were not comparable at the beginning of the intervention and that their listening performance followed different trajectories over time.

Table 3.

Means (and standard deviations) for question types (in %).

In addition, Table 3 shows that, at all three testing times, all groups were more successful at correctly answering questions addressing information explicitly stated in the vlogs. A repeated-measure ANOVA, conducted after verifying that the data adhere to the assumptions of homoscedasticity and normal distribution of variance, confirmed a main effect of question type (F (1, 46.5) = 123.78, p < 0.0001)

3.2. Listening Performance on the Qualitative Measure: Scores on First and Last Implicit Listening Strategies Training

Each implicit strategies training session with pairs of participants from the two experimental groups was recorded. Verbalisations of the 17 participants who took part in all five intervention sessions were analysed in terms of participants’ ability to identify, retell and make connections between key elements from the vlog excerpt. Table 4 shows participants’ scores for the first (TI) and last (T5) training sessions and offers a different perspective on participants’ listening performance.

Table 4.

Listening performance scores on the first (T1) and last (T5) training sessions.

Overall, the changes observed from T1 to T5 can be seen in terms of: (1) better ability to verbalise key content of the vlog (from − to +, as for A04, A06, A12 and B01); (2) ability to establish better connections between different elements of the vlog (from lower to higher score on 4, as for B11, B09, A14 and B05); or (3) a combination of better ability to verbalise key content of the vlog and better ability to establish better connections between different elements of the vlog (for A01). Overall, participants remained at the same level or made gains on either the ability to discuss key concepts from the vlog or the ability to make more elaborate connexions between different elements of the vlog. These results are in sharp contrast with those obtained on the listening comprehension tests discussed above.

This discrepancy in listening performance measured quantitatively and qualitatively is evident with participant B09. While his listening performance on the three listening comprehension tests remained stable over time (score of 4/8 at T1, T2 and T3), qualitative observations of his listening performance showed great changes from T1 (score = 2+) to T5 (score = 4+). At T1, B09′s verbalisations (see Example 1) showed repetition of units that included keywords (partement, “apartment”; beaucoup cher, “very expensive”) with no connections, and were therefore associated with a score of 2+6.

| 1. | B09 | Elle dit: le: partement (.) trop (.)↘grand↘ “She says: the: apartment (.) too (.) big↘” |

| R. | Oui “Yes” | |

| B09 | Beaucoup cher (.) “Very expensive (.)” |

A closer look at B09′s verbalisations in terms of explicit and implicit information shows that the only relevant information he identified (about the apartment being expensive) was stated explicitly by the vlogger.

At T5, B09′s verbalisations were generally characteristic of level 4+7. He first mentioned the majority of the explicitly stated key elements from the excerpt, then, when prompted to summarise the vlog, was able to connect these elements in a narrative-like sequence (see Example 2)

| 2. | Hum (.) De: Prome(.) promener dans quartier: je pense que (.) elle a cherché↗ l’appartement: Chien (.) Chien (.) [euh] Son chien↗ accepté: ou non↘ |

| “Hum (.) to: wa(.) walk in the neighbourhoo:d I think that (.) she looked for↗ the apartment: dog(.) dog (.) [uh] her dog↗ accepte:d or not↘” |

B09 continues to add to his summary and it is here that we see evidence of implicit information processing when he mentions where he thinks the vlogger lives (see Example 3). Information about the vlogger living in Montreal was not explicitly addressed in the vlog (i.e., at the beginning of the excerpt the vlogger mentions she is looking for a new apartment, but she wants to stay in the same neighbourhood. At the end of the excerpt, she asks for help finding an apartment in Montreal. She thus never explicitly says she lives in Montreal).

| 3. | [Euh] Je pense que elle déjà: ↗ (.) habite Montréal↘ |

| “[uh] I think that she already: ↗ (.) lives in Montreal↘” |

It thus seems that the qualitative data capture the participants’ listening comprehension competence differently than the quantitative measure. These results are discussed in the next section.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The present small-scale study sought to answer the following research question: Does implicit teaching of listening strategies and metacognition help foster oral comprehension of adults with low levels of education who are learning French Lx? Two types of data were gathered: quantitative data were collected through listening comprehension tests used before and after the intervention and qualitative data were obtained by analysing participants’ verbalisations during the first and last implicit strategies training sessions.

Results on the listening comprehension tests showed that the three groups were not comparable throughout the study and that no effect of the experimental treatment on the participants’ listening performance could be observed. The variation observed over time is however difficult to interpret, as the experimental groups did not perform similarly, and the control group’s performance was similar to that of Group A. In addition, other linguistic variables (i.e., lexical and grammatical knowledge) that were not controlled for might have influenced participants’ performance. Another factor that needs to be acknowledged is the possible teacher effect: since the three groups had different teachers, and since we did not monitor what was taught in class, teachers might have influenced students’ performance. At this point, although the less-skilled listeners in our study (Group A) did seem to benefit more from the intervention, it is thus difficult to conclude on positive effects of the experimental treatment, unlike Vandergrift and Tafaghodtari’s (2010) original study in which literate adolescent learners of French made clear progress in their listening journals: the positive effect we measured was not significant and could not apply to all participants, who were generally poor listeners. This weaker effect is not surprising, considering the extent to which the original procedure was adapted to create learning conditions better suited for SLIFE. Our participants thus had much fewer opportunities to explain and reflect on the decisions they made while listening, impacting the degree to which they could actually act on their listening processes.

This finding must, however, be interpreted with caution, as we must keep in mind the characteristics of our participants. It is indeed possible that some factors hindered the true manifestation of the participants’ competence on the listening comprehension tests. First, the format of the test (paper and pencil), of the questions (multiple-choice) and their layout (2D black and white pictograms) might have played a role. According to Huettig and Mishra (2014), SLIFE underperform when 2D black and white images are used, compared to when they see real colour pictures: participants might have misinterpreted these abstract representations. The language and cultural expectations surrounding an assessment situation might also have been fairly unfamiliar to our participants (Loring 2017), who might have underperformed in this context. Poor performance of SLIFE in our detail-oriented questionnaires is also consistent with Henrich et al. (2010) findings suggesting that most cultures around the world favour holistic reasoning instead of analytic reasoning (i.e., participants might have understood the key and global ideas in the excerpts, but paid little to no attention to the details targeted in the questionnaires). All of these elements underscore the poor ecological validity of performing a decontextualised task such as answering a questionnaire for SLIFE. Thus, the groups’ performance on the tests might be attributed to a combination of these factors, minimising the importance of comprehension per se in the measure.

Nevertheless, before reaching hasty conclusions about the ineffectiveness of the treatment, we must turn to the qualitative data obtained from the 17 participants from Group A and Group B, which offer a more nuanced perspective. Indeed, while eight participants remained at the same level throughout the study, the remaining ones made gains either on the ability to discuss concepts actually related to the content of the vlog (n = 4) or the ability to make more elaborate connections between different elements of the vlog excerpt (n = 4), or both (n = 1). Even though we do not have access to the same data from the participants in the control group and therefore cannot attribute those changes observed to the experimental treatment, we believe that these qualitative data captured more finely how participants’ listening performance unfolds, although these results might also not truly reflect the participants’ actual comprehension. In this regard, different limitations can be identified.

First, building on Young-Scholten and Strom’s (2006) and Tarone’s (2010) findings that adult non-readers are able to repeat content words, participants might have successfully been able to reproduce a string of phonemes forming a word or a phrase associated with a key element in the vlog without actually having understood its meaning or importance. Second, the content of the participants’ verbalisations may have been affected by their linguistic abilities (i.e., their grammatical and lexical knowledge, which were not controlled for), their retrieval capacities or the degree to which one is detailed-oriented or talkative: some may have understood more than they actually said and others may have established more sophisticated connections between different segments of the vlog than they expressed. In addition, to our knowledge, our study is the first to have used a free recall protocol with SLIFE. Our adaptation of Kim’s (1995) coding scheme to assess participants’ ability to successfully retell the content of a vlog is still at an exploratory stage. Because of our participants’ limited production skills, we relied exclusively on the phonological encoding of our participants’ verbalisations to assess their ability to make more or less sophisticated connections between words and/or phrases they understood. The first author’s field notes indicate that other cues such as gestures or gaze might have provided further evidence of ongoing language processing that could have been useful to establish participants’ score. Thus, further research assessing the validity of this adaptation, and SLIFE language processing capacities in general, is desperately needed.

Facing these seemingly inconsistent results from our two data sources, one must bear in mind that our two measures targeted very different listening processes and exerted different cognitive and linguistic demands on the participants. On the one hand, the pen-and-paper oral comprehension tests required the participants to attend to both main and secondary ideas in the vlog, to keep them in working memory, to decode the answer sheets and the questions asked, and to finally select an answer. This testing format was thus very cognitively demanding, requiring participants to continuously shift their memory and attentional resources from the vlog content to the answer sheet. On the other hand, the free recall protocol used during the intervention required the participants to attend primarily to words and phrases they decoded, memorise them and use their linguistic repertoire to verbalise the elements they could retrieve from memory. Similar to the pen-and-paper test, this task imposed important memory and retrieval demands, but only on the content decoded by the participant. In addition, the free recall protocol was more linguistically demanding than the pen-and-paper test: the participants had to draw on their linguistic resources to reveal what they had gathered from the vlogger. Thus, the two data sources do not shed light on the same processes and constraints that mediate listening performance. They thus should be seen as complementary instead of considered as showing inconsistent results. If both measures are adapted so as to lower their memory and linguistic demands and to target key elements from the vlog, they could be used in combination to prepare learners to meet the school’s home program oral comprehension objective at this level (i.e., “Comprendre des informations, les repérer et faire des déductions simples dans une courte vidéo ou un court texte audio et répondre à des questions s’y rapportant”; “Understand, identify and make simple inferences about content of short videos or short audio texts and answer related questions about them”).

Despite the limitations of our instruments and small sample size, the current study has nevertheless responded to the call from Tarone (2010) to replicate “SLA studies in populations of illiterate and low-literate learners” (p. 77), being the first, to our knowledge, to have addressed implicit listening strategies training for SLIFE, partially replicating Vandergrift and Tafaghodtari (2010). The specific focus on this understudied population yields important new insights that can assist the field of ISLA to better integrate this population into its research agenda. For example, in light of our findings, it appears that a process-product research design might be better suited to capture SLIFE’s actual Lx skills than a before-and-after design. Indeed, pretest–posttest designs, widely used in ISLA research, rely on the cultural assumptions that: (1) individual performance prevails over group performance; and (2) that performance on one-time decontextualised tasks is meant to display the depth of one’s individual knowledge or skills. However, SLIFE tend to underperform in these conditions; these cultural practices are at odds with their own way of learning and the reasons motiving learning in the first place (DeCapua 2016). In addition, our findings have also exposed the fact that, even though we know much about SLIFE’s characteristics, very little is known about how they deploy their cognitive and attentional resources when faced with the task of processing authentic oral input. Further research is thus needed to validate measures meant to accurately describe SLIFE’s depth of language processing and awareness, as these are key cognitive factors mediating Lx learning (Hulstijn 2019). We hope that other ISLA researchers will be inspired to carry out classroom research with SLIFE. More attention to this population will ultimately allow for a more comprehensive assessment of the extent to which general Lx learning theories and hypotheses, based on highly educated and literate Lx learners, are valid and reliable.

Author Contributions

The present project was designed by C.L., as his MA thesis (under the S.B.’s supervision). The design and the data collection were thus planned and executed by the C.L., supervised by the S.B. during all phases, and by V.F., who was involved regarding the designing of the tests as well as for the quantitative and qualitative analyses. The manuscript itself was first drafted by C.L., but all three authors offered substantive suggestions contributing to the manuscript in its present form.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Julie Damiens, Frédérique Lafleur et Wolf Nagel, the teachers who kindly opened the doors of their classrooms for us to conduct our study, as well as their students who generously accepted to participate in the study. We also wish to thank Christina Driedger and Myriam Paquet-Gauthier for reading the earlier drafts of this article and for their useful suggestions. We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix B. Vlog Excerpts Used during the Intervention Sessions

Tellement mom. (2017, Sept. 22). Vlog – Popote d’automne (22 septembre 2017) [Online document]. Retrieved at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l4UQHhumyIA

The excerpt from 0:00:00 to 0:01:17 was used for test A.

Camille Cuisine. (2016, Feb. 16). Camille Cuisine | Mon épicerie de la semaine chez Métro, Super C, Costco [Online document]. Retrieved at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hilvURsJeDE

The excerpt from 0:00:00 to 0:01:17 was used for test B.

PL Cloutier. (2017, May 27). JE ME SUIS FAIT VOLER MON VÉLO [VLOG] | PL Cloutier [Online document]. Retrieved at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MVLUVuUEWMI

The excerpt from 0:00:35 to 0:02:02 was used for test C.

Cath & Jay. (2017, July 5). NOTRE NOUVEAU CHEZ-NOUS!!! | 3 juillet 2017 [Online document]. Retrieved at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rXhwKcOprVc

The excerpt from 0:07:35 to 0:08:47 was used for Group A’s second intervention session and Group B’s third intervention session.

Sara-Karina. (2017, Oct. 18). Mon frigo est vivant… / 1ère commande en ligne chez Métro!:D / Vlog #492 [Online document]. Retrieved at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aRgc5DiNRUQ

The excerpt from 0:00:27 to 0:01:24 was used for Group A’s third intervention session and Group B’s second intervention session.

Karine Pothier. (2014, Nov. 14). UPDATE sur ma vie ! / Déménagement, mariage & enfants ! [Online document]. Retrieved at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=crDr5eZ3HG8

The excerpt from 0:04:24 to 0:05:33 was used for both Group A and Group B’s fourth intervention session.

Emma Bossé Vlog. (2017, Dec. 14). JE DÉMÉNAGE ENCORE? [Online document]. Retrieved at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ryH01ZpeTE

The excerpt from 0:09:07 to 0:10:34 was used for both Group A and Group B’s first intervention session.

Emma Bossé Vlog. (2018, Mar. 12). JE VISITE DES APPARTS [Online document]. Retrieved at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZBnvzpzW1tA

The excerpt from 0:08:54 to 0:10:01 was used for both Group A and Group B’s fifth intervention session.

Appendix C

Table A1.

Qualitative data coding scheme.

Table A1.

Qualitative data coding scheme.

| Score | Descriptors and Excerpts |

|---|---|

| 1− | A few isolated words are uttered as if reciting a list. They are generally not related to the content of the excerpt. |

| “travail (.) que que travail [euh] je ne sais pas(.) K(.) K (.) Koodo Koodo telephone” [A06-01-03] ‘work (.) that that work [uh] I do not know K (.) K (.) Koodo Koodo telephone’ | |

| 1+ | A few isolated words are uttered as if reciting a list. They are generally closely related to the key content of the excerpt. |

“Appartement(.)Montréal  C’est argent C’est argent  Petit Petit  Argent Argent  [euh] Petit [euh] Petit  Argent Argent Montréal Montréal ” [A14-01-03] ” [A14-01-03]‘Apartment (.) Montreal  It’s money It’s money Small Small Money Money [uh] Small [uh] Small Money Money Montreal Montreal ’ ’ | |

| 2− | Isolated phrases and words are uttered as if reciting a list. They are generally not related to the content of the excerpt. |

“Elle regarde Prix Prix Elle regarde Elle regarde Prix [indistinct mumble] Prix [indistinct mumble]  Couleur blanc les (pointing at the walls) Couleur blanc les (pointing at the walls) ” [A01-01-03] ” [A01-01-03]‘She looks at  Prices Prices She looks at She looks at Prices [indistinct mumble] Prices [indistinct mumble]  Colour white the (pointing at the walls) Colour white the (pointing at the walls) ’ ’ | |

| 2+ | Isolated phrases and words are uttered as if reciting a list. They are generally closely related to the key content of the excerpt. |

“Prend l’appartement . Nouvel appartement . Nouvel appartement . (3.0) Plus cher . (3.0) Plus cher . (5.5) Plus petit . (5.5) Plus petit ” [B11-01-03] ” [B11-01-03]‘Takes the apartment  . New apartment . New apartment . (3.0) More expensive . (3.0) More expensive . (5.5) Smaller . (5.5) Smaller .’ .’ | |

| 3− | Connected phrases are uttered. The connexions established by the participants are generally not related to the content of the excerpt. |

| “Appartement problème (.) c’est fenêtre appartement payer par mois problème” [A04-01-03] ‘Apartment problem (.) it’s window apartment paying each month problem’ | |

| 3+ | Connected phrases are uttered. The connexions established by the participants are generally closely related to the key content of the excerpt. |

“Elle a rendez-vous (.) la banque la semaine prochaine . Ah: Elle a déménagé Montréal . Ah: Elle a déménagé Montréal ” [B06-01-03] ” [B06-01-03]‘She has appointment (.) the bank next week  . Ah: She moved Montreal . Ah: She moved Montreal ’ ’ | |

| 4− | Connected phrases are uttered in the form of a (partial) narration. The content of the (partial) narration is not entirely related to the excerpt. |

| “La madame la maison difficile parce que la madame la maison grande pas fenêtre. Rendez-vous banque pour le condo condo condo (.) parce que arrête sortie: difficile pas d’argent.” [B13-01-03] ‘The woman the house difficult because the woman the house big no window. Appointment bank for the condo condo condo (.) because stop going out: difficult no money.’ | |

| 4+ | Connected phrases are uttered in the form of a (partial) narration. The content of the (partial) narration is generally closely related to the key content of the excerpt. |

“Elle a appartement très gros (euh) Elle a (.) payé plus plus cher (.) Elle a fatigué (.) Elle a sortir autre appartement Montréal (.) Elle amie ” [B03-01-03] ” [B03-01-03]‘She has apartment very big (uh) She has (.) paid more more expensive(.) She has tired (.) She went out other apartment Montreal (.) She friend  ’ ’ |

References

- Bigelow, Martha, and Elaine Tarone. 2004. The role of literacy level in second language acquisition: Doesn’t who we study determine what we know? TESOL Quarterly 38: 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, Martha, and Patsy Vinogradov. 2011. Teaching adult second language learners who are emergent readers. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 31: 120–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, Martha, Robert DelMas, Kit Hansen, and Elaine Tarone. 2006. Literacy and the processing of oral recasts in SLA. TESOL Quarterly 40: 665–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Gillian. 1995. Dimensions of difficulty in listening comprehension. In A Guide for the Teaching of Second Language Listening. Edited by David J. Mendelsohn and Joan Rubin. San Diego: Dominie Press, pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Condelli, Larry, Heide Spruck Wrigley, and Kwang Suk Yoon. 2009. “What works” for adult literacy students of English as a second language. In Tracking Adult Literacy and Numeracy Skills. Edited by Stepehn Reder and John Bynner. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 132–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, Jeremy. 2010. Metacognitive instruction for helping less-skilled listeners. ELT Journal 65: 408–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCapua, Andrea. 2016. Reaching students with limited or interrupted formal education through culturally responsive teaching. Language and Linguistics Compass 10: 225–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCapua, Andrea, and Helaine W. Marshall. 2015. Reframing the conversation about students with limited or interrupted schooling: From achievement gap to cultural dissonance. NASSP Bulletin 99: 356–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, Itala. 2015. Training in metacognitive strategies for students’ vocabulary improvement by using learning journals. Profile Issues in TeachersProfessional Development 17: 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Suzanne. 2017. Research into practice: Listening strategies in an instructed classroom setting. Language Teaching 50: 107–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Suzanne, and Ernesto Macaro. 2008. Strategy instruction in listening for lower-intermediate learners of French. Language Learning 58: 747–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Suzanne, Denise Santos, and Robert Vanderplank. 2008. Listening comprehension and strategy use: A longitudinal exploration. System 36: 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, Joseph, Steven J. Heine, and Ara Norenzayan. 2010. The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33: 61–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huettig, Falk, and Ramesh K. Mishra. 2014. How literacy acquisition affects the illiterate mind—A critical examination of theories and evidence. Language and Linguistics Compass 8: 401–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulstijn, Jan H. 2019. An individual-differences framework for comparing nonnative with native speakers: Perspectives from BLC theory. Language Learning 69: 157–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, Philip. 2017. The pedagogical implications of orality on refugee ESL students. Dialogues: An Interdisciplinary Journal of English Language Teaching and Research 1: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hae-Young. 1995. Intake from the speech stream: Speech elements that L2 learners attend to. In Attention and Awareness in Foreign Language Learning. Edited by Richard Schmidt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmidis, Mary H., Maria Zafiri, and Nina Politimou. 2011. Literacy versus formal schooling: Influence on working memory. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 26: 575–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loring, Ariel. 2017. Literacy in citizenship preparatory classes. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 16: 172–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, Alison, and Susan M. Gass. 2016. Stimulated Recall Methodology in Applied Linguistics and L2 Research. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Leslie. 1999. Language socialization research and French language education in Africa: A Cameroonian case study. Canadian Modern Language Review 56: 329–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Lourdes. 2019. SLA and the study of equitable multilingualism. The Modern Language Journal 103: 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, Michael. 2011. Teaching and Researching: Listening, 2nd ed.Harlow: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Kyoko. 2005. Development of a listening strategy intervention program for adult learners of Japanese. International Journal of Listening 19: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strube, Susanna, Ineke van de Craats, and Roeland van Hout. 2013. Grappling with the oral skills: The learning processes of the low-educated adult second language and literacy learner. Apples Journal of Applied Language Studies 7: 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tafaghodtari, Marzieh H., and Larry Vandergrift. 2008. Second and foreign language listening: Unraveling the construct. Perceptual and Motor Skills 107: 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarone, Elaine. 2010. Second language acquisition by low-literate learners: An under-studied population. Language Teaching 43: 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergrift, Larry. 2006. Second language listening: Listening ability or language proficiency? The Modern Language Journal 9: 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergrift, Larry. 2008. Learning strategies for listening comprehension. In Language learning Strategies in Independent Settings. Edited by Stella Hurd and Tim Lewis. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 84–102. [Google Scholar]

- Vandergrift, Larry, and Jeremy Cross. 2017. Replication research in L2 listening comprehension: A conceptual replication of Graham & Macaro (2008) and an approximate replication of Vandergrift & Tafaghodtari (2010) and Brett (1997). Language Teaching 50: 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergrift, Larry, and Christine C. M. Goh. 2012. Teaching and Learning Second Language Listening: Metacognition in Action. New York, London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vandergrift, Larry, and Marzieh H. Tafaghodtari. 2010. Teaching L2 learners how to listen does make a difference: An empirical study. Language Learning 60: 470–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolvin, Andrew D. 2018. Listening processes. In The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, Online ed. Edited by John I. Liontas. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young-Scholten, Martha. 2013. Low-educated immigrants and the social relevance of second language acquisition research. Second Language Research 29: 441–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young-Scholten, Martha, and Nancy Strom. 2006. First-time L2 readers: Is there a critical period? In Low Educated Adult Second Language and Literacy. Edited by Jeanne Kurvers, Ineke van de Craats and Martha Young-Scholten. Utrecht: LOT, pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Informed consent from all participants was obtained before their inclusion in the study, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Université Laval (2017-368/01-02-2018). |

| 2 | The education centre does not collect information regarding the length of residence, nor prior years of formal schooling of their students. General information regarding participants reported here came from our informal discussions with them, between the intervention sessions. |

| 3 | According to the centre’s house program, students at levels 2 and 3 are very similar in terms of oral comprehension and oral production skills. However, their written production and comprehension abilities differ slightly: while students in level 2 can read and write simple, predictable sentences, level 3 students can read and write marginally longer paragraphs or texts as long as they remain simple and predictable. |

| 4 | References for all the vlog excerpts are provided in Appendix B. |

| 5 | To make the modelling phase appear realistic to the learners, both teachers read the first author’s field notes about what pairs of participants said they understood after the first, second and third viewings, and they attempted to closely emulate a free recall performance similar to their group’s. |

| 6 | Isolated phrases and words are uttered as if reciting a list. They are generally closely related to the key content of the excerpt (2 + score). |

| 7 | Several connected phrases are uttered. The participant offers a (partial) narration of key content of the excerpt (4 + score). |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).