Language Education for Forced Migrants: Governance and Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Context

2.1. Asylum and Refugee Resettlement in the United Kingdom

Owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it (Article 1A (2): ibid.).

“The support for the refugees on the managed programme is gold standard. We help with so many aspects of resettlement such as getting homes ready, placing children in schools, registering with the local health centre, helping them with the benefits system… people granted refugee status through the asylum process have a very different experience, indeed”.(J.S.)

2.2. Refugee Integration in Wales

3. Methodology

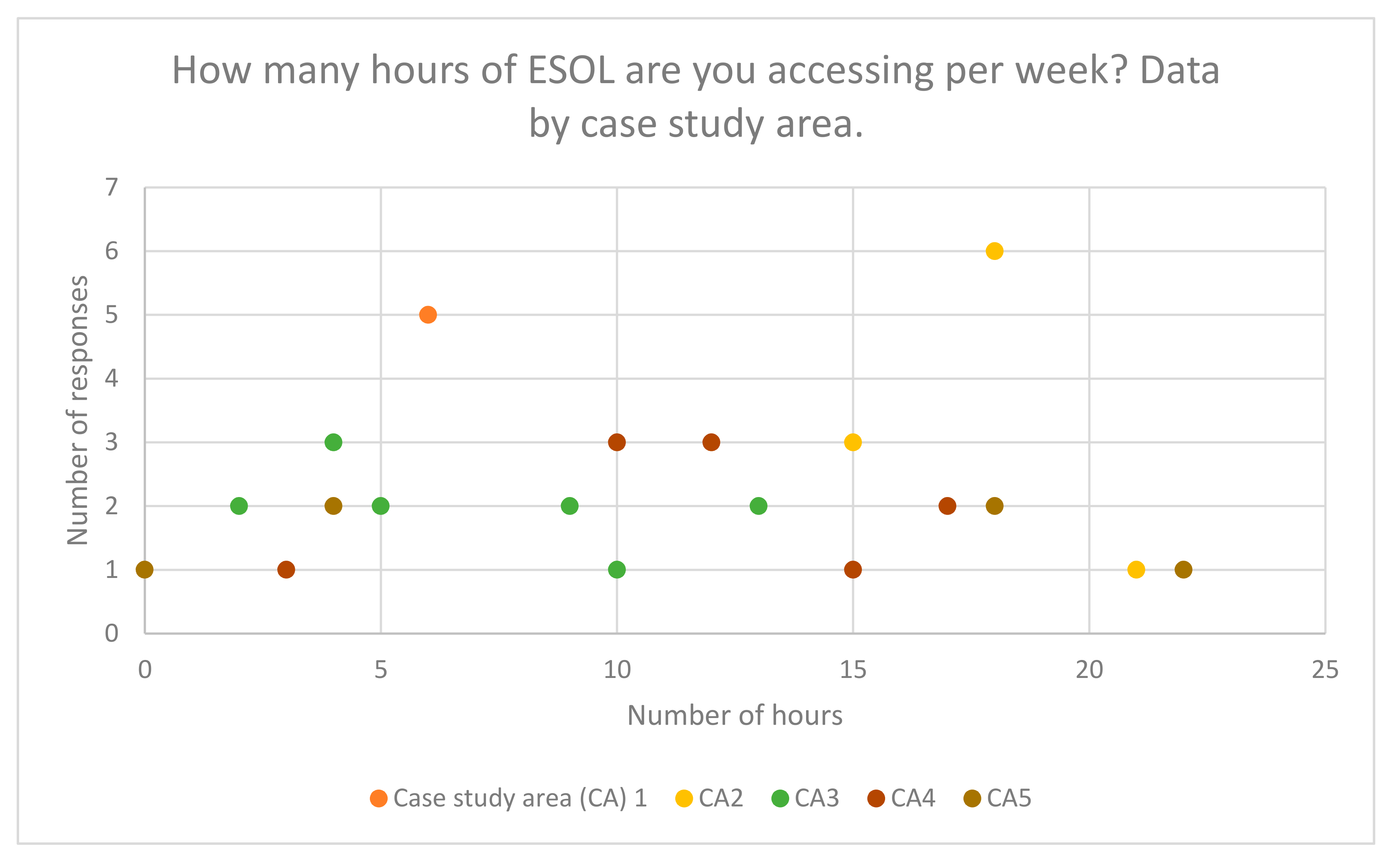

4. Findings

“effectively identify an individual’s ESOL requirements and be responsive to those needs through the most appropriate delivery arrangements and range of providers within a local area”.(ibid., p. 7)

- 1

- IHL: What’s the problem?

- 2

- OL: For babies I cannot go college but for baby.

- 3

- IHL: Okay

- 4

- Interpreter: It’s the problem with the for the nursery for the children there is no fund for the nursery so they can’t leave their children.[…]

- 5

- Int: In [area 2, the council] are paying for the nursery

- 6

- IHL: So [area 5] they can’t have no money for childcare and [area 2] they do?

- 7

- Int: Yes.[…]

- 8

- IHL: Do all the women have this problem?

- 9

- Many voices: Yes, yes(Excerpt from focus group, case study area 5)

- 1

- Interpreter: She said that is the biggest thing that they are stuck in and they want to go on the bus and the bus driver ask them something and they want—they don’t know how to reply

- 2

- So yesterday somebody was talking to her whatever she was very [shrug shoulders, shake head]

- 3

- but her daughter was helping her, her younger daughter to translate […]

- 4

- She like to talk with her neighbour as well but the language barrier […]

- 5

- I haven’t got opportunity to learn, I haven’t got opportunity to learn that’s what she’s saying, haven’t got opportunity to learn the language(Excerpt from focus group, case study area 5)

- 1

- IHL: Is there childcare? Is there childcare?

- 2

- KA: Here in college?

- 3

- IHL Yeah

- 4

- [many voices]: No[…]

- 5

- Interpreter: No there is not, not in college no, no it’s not it’s only put them in private nurseries

- 6

- IHL: So, does- does private nurseries get paid by the council?

- 7

- Int: Yep- yes

- 8

- IHL So that means you can go to college?

- 9

- Int: Yes

- 10

- IHL: Good. Other areas=

- 11

- Int: = sorry

- 12

- It’s only for one year, yes?

- 13

- FA: Yes

- 14

- Int: Only for one year [from council]

- 15

- IHL Ah, and then after you=

- 16

- Int: =till now we don’t know.(Excerpt from focus group, case study area 2)

- 1

- IHL: So, beyond VPRS, will they have access to childcare as well?

- 2

- VT: I don’t know to be honest, I’m assuming that it is continuing

- 3

- because they’re still attending the ones that needed childcare

- 4

- even though they’re beyond the 12 months

- 5

- so I’m assuming that the funding is still there.(Excerpt from interview with ‘VT’ community learning commissioner, case study area 1)

- 1

- AB: I give you example:

- 2

- when coming to college we have to uh buy a weekly ticket

- 3

- £14.50 and for one person

- 4

- if we come with his wife uh £29 a week-weekly

- 5

- and if they want to come as a family to [xxx] they have to pay as a family ticket £12 this will cost I’m sure more than £150 monthly, yeah?(Excerpt from focus group, case study area 5)

- 1

- Caseworker: The council have been in talks with [the bus company] for over well since last September

- 2

- and the reason is [the council] only wants to fund quarterly season tickets uh

- 3

- but unfortunately the bus company doesn’t do season tickets.

- 4

- Also [the council] only wants to allow travel in the area not the further area as well so it’s hard to get that organised.(Excerpt from focus group in case study area 3)

- 1

- EC: […] the ESOL provision is here. They’re talking about us giving them extra lessons but we are working full time.

- 2

- When else do they want us to teach them?

- 3

- Do they want us to go to their houses? They being the council.

- 4

- Because our provision is here.

- 5

- Traditionally, we’ve got classes on a Tuesday in [this part of the local authority] because we haven’t had as many students in [the other district] as we have [here].(Excerpt from interview with ESOL co-ordinator, further education provider, case study area 3)

- 1

- VT: I think we do need 3 different levels, I think we have people of 3 different levels.

- 2

- We have one class that are learning the alphabet from scratch,

- 3

- but we’ve also got [ ] who is struggling to make the figures and do the alphabet. […]

- 4

- I really think we do need the 3 classes.

- 5

- RA: The only issue is that [national education provider] say they need 8 for a class […]

- 6

- There are obviously people out there who need it.(Excerpt from interview with voluntary organiser (‘VT’) and VPRS co-ordinator (‘RA’) case study area 4)

- 1

- And sometimes because there are people of a lower level […]

- 2

- they can’t catch up quickly.

- 3

- They need their own very low level.

- 4

- Beginners level, from the letters […]

- 5

- they are struggling, they get angry, the class is tense, believe me, and a few problems happened in the class (VPRS participant).

- 1

- It’s heart-breaking, impossible really, to turn anyone away from a class.

- 2

- But the truth is that having pre-entry level students

- 3

- who can’t yet identify the letters of the alphabet

- 4

- in the same classroom as learners at entry level 1 or 2 is a big problem for everybody (ESOL teacher)

- 1

- You get people who don’t even know the alphabet

- 2

- and you get people who have been coming for two years and everyone becomes frustrated

- 3

- and the lecturer is tearing her hair out. (ESOL manager)

- 1

- They are all in the same class

- 2

- and we’ve got a range of levels because some of them have been here for an additional year and more families are arriving

- 3

- so there is a mix in the class.

- 4

- It’s the numbers, it’s just not financially viable for the college to put them in separate levels.(ESOL manager)

“To […] have systems that accurately capture the progress made by ESOL learners, reflecting the individual modes of learning, and the length of time necessary for ESOL learners to progress”.

- 1

- It would have been helpful to have someone talk in lay-persons terms about what ESOL is, how it’s provided, who provides it, what the accreditation is […]

- 2

- […] when we first took families there were no clearly defined expectations about language-

- 3

- How much was enough? How much wasn’t enough?

- 4

- […] at the start it would have been good to have spoken about the expectations and how ESOL is delivered,

- 5

- and that could have come from Welsh Government.(Excerpt from interview with local authority resettlement officer)

- 1

- We are not responsible for organising the Syrian’s ESOL(Excerpt from interview with ESOL manager at a further education college)

- 1

- It’s really frustrating because we are supposed to be a college providing ESOL

- 2

- and we are saying ‘oh sorry we can’t cater for you’.

- 3

- Who else is supposed to be doing it?

- 4

- If the college can’t provide it.(Excerpt from interview with ESOL manager at a further education college)

- (iv)

- Formal vs. informal language learning

- 1

- Leila is a wonderful woman,

- 2

- hugely motivated to learn English—

- 3

- not least so that she might be able to speak with her children and their teachers in English.

- 4

- But she’s never been to school.

- 5

- She finds exams too challenging. She’s awfully upset.(Excerpt from interview with community volunteer)

- 1

- I am not happy in school, because it is like an academic course,

- 2

- so we are not young to study academic,

- 3

- only we can improve our language in practical situations(Except from interview with VPRS participant)

- 1

- Interpreter: They say if they work help them to learn English […]

- 2

- Uh she say she know someone he don’t study but he go to have work

- 3

- and he never studied but his English now is very improved

- 4

- IHL: Who is that?

- 5

- Int: He is his cous-her cousin he live in London now and he got a job(Excerpt from focus group, case study area 1)

- 1

- All of the refugees would want a job opportunity where they could work and learn English at the same time.(Excerpt from interview with VPRS caseworker)

5. Discussion

5.1. Time

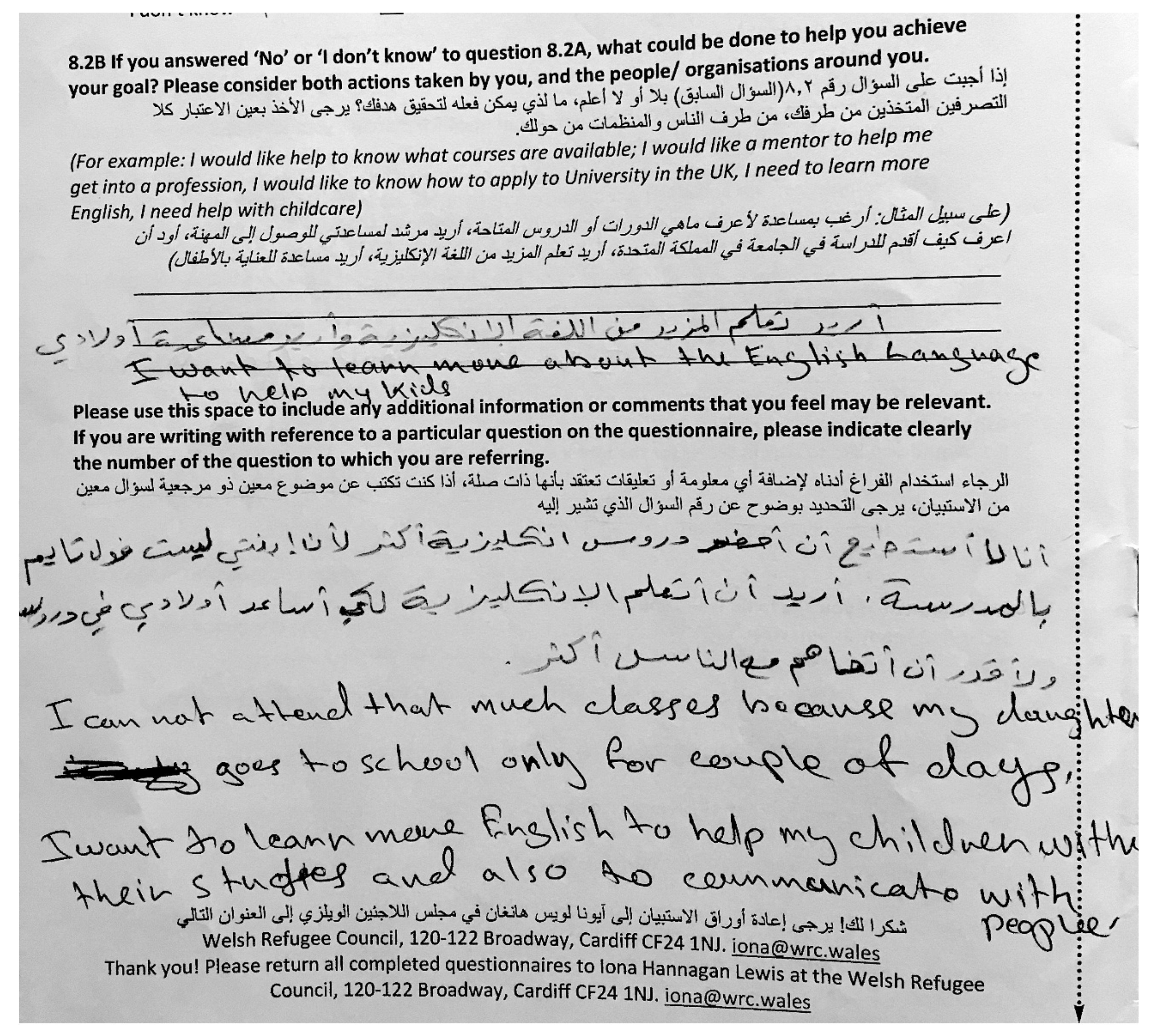

5.2. A Flexible Approach

“… institutions such as government employment offices, welfare offices and banks loom large in the lives of linguistic minority people and students’ interactions in English can be coloured by miscommunication, hostility and sometimes racism”.

5.3. Alternative Options

“Take action on the issues which they identify as important, and evaluate their progress and the effectiveness of their programme as they go along”.

“Provide a challenging but safe environment for critical discussion which start by exploring the students’ own ideas, thoughts, and experiences, gradually moving into discussion of ideas drawn from outside”.

5.4. Concluding Remarks

“Offer provision to meet the variety of needs of learners, taking into account: appropriate levels, location, timetables and the educational backgrounds of learners”.(p. 16)

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

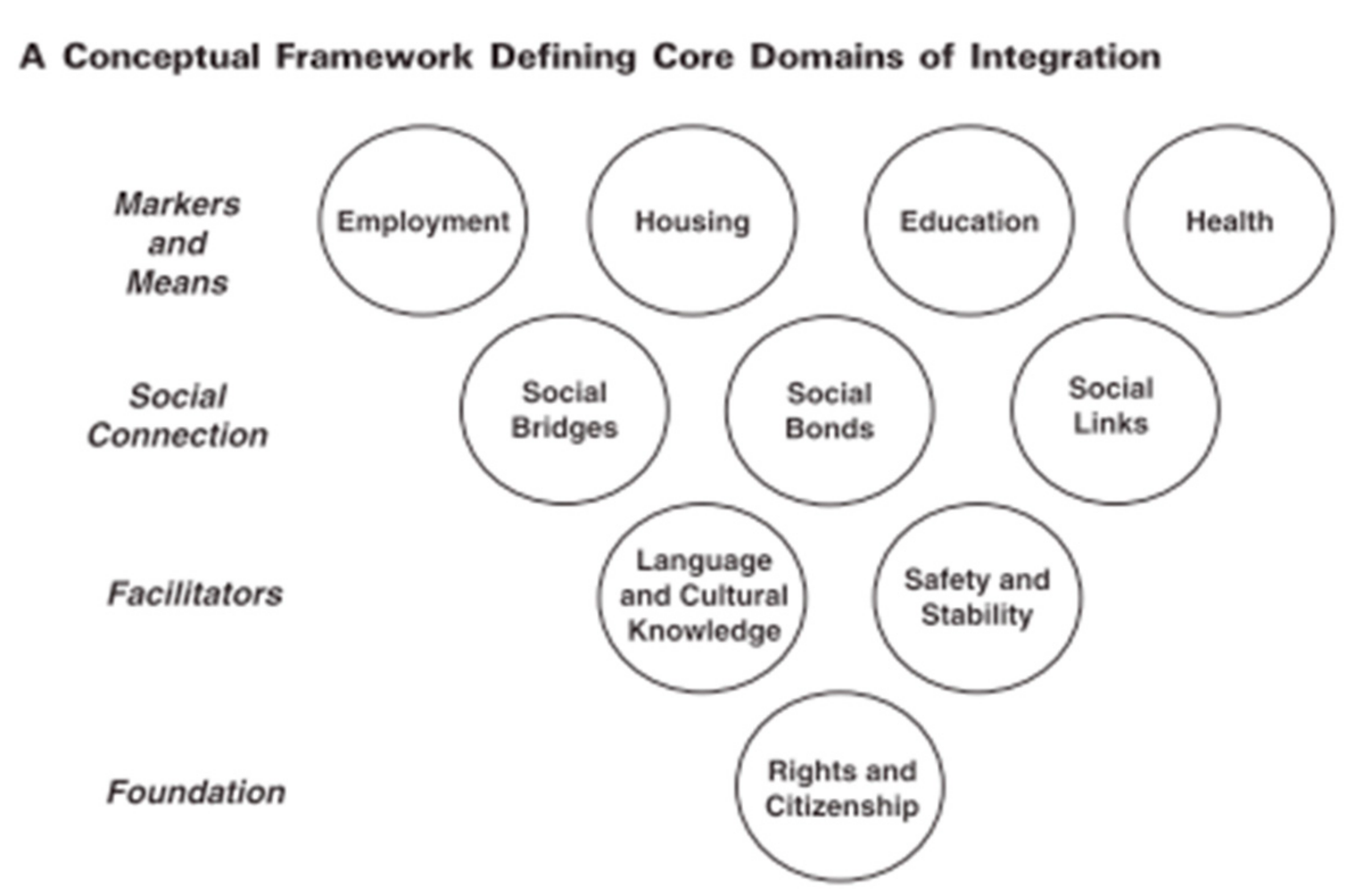

- Ager, Alastair, and Alison Strang. 2008. Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Refugee Studies 21: 166–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APPG on Refugees. 2017. Refugees Welcome? The Experience of New Refugees in the UK. Available online: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/assets/0004/0316/APPG_on_Refugees_-_Refugees_Welcome_report.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- BERA. 2011. Ethical Guidlines for Educational Research. Available online: http://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2011 (accessed on 13 September 2019).

- Bolt, David. 2018. An Inspection of the Vulnerable Persons’ Resettlement Scheme: August 2017–January 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/705155/VPRS_Final_Artwork_revised.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Bryman, Alan. 2016. Social Research Methods, 5th ed. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Chick, Mike. 2019. Refugee resettlement in rural Wales—A collaborative approach. In ESOL Provision in the UK and Ireland: Challenges and Opportunities. Edited by Freda Mishan. Dublin: Peter Lang Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, Melanie, Becky Winstanley, and Dermot Bryers. 2015. Whose Integration? A Participatory Esol Project in the UK. In Adult Language Education Migration: Challenging Agendas in Policy and Practice. Edited by James Simpson and Anne Whiteside. New York: Routledge, pp. 214–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, Melanie, Dermot Bryers, and Becky Winstanley. 2018. Our Languages: Sociolinguistics in Multilingual Participatory ESOL Classes. Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies (234). Available online: https://www.academia.edu/35839204/WP234_Cooke_Bryers_and_Winstanley_2018._Our_Languages_Sociolinguistics_in_multilingual_participatory_ESOL_classes (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Edwards, Rosalind. 1998. A Critical Examination of the Use of Interpreters in the Qualitative Research Process. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 24: 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, Paul. 1972. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann, Friedrich. 2006. Integration and integration policies: IMISCOE Network Feasibility Study. Amsterdam: IMISCOE. Available online: http://www.efms.uni-bamberg.de/pdf/INTPOL%20Final%20Paper.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Higton, John, Jatinder Sandhu, Alex Stutz, Rupal Patel, Arifa Choudhoury, and Sally Richards. 2019. English for Speakers of Other Languages: Access and Progression; London: Department for Education. Available online: http://www.gov.uk/government/publications (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Home Office. 2017. Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS): Guidance for Local Authorities and Partners. July. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/631369/170711_Syrian_Resettlement_Updated_Fact_Sheet_final.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Home Office. 2018. Funding Instruction for Local Authorities in the Support of the United Kingdom’s Resettlement Scheme. Financial Year 2018–2019. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/722154/Combined_local_authority_funding_instruction_2018-2019_v2.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Home Office. 2019. New Global Resettlement Scheme for the Most Vulnerable Refugees [Press Release]. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-global-resettlement-scheme-for-the-most-vulnerable-refugees-announced (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Home Office, Department for Communities, Local Government, and Department for Education. 2016. Interim Guidance on Commissioning ESOL for Those on the Syrian Vulnerable Person’s Resettlement Scheme (VPRS) and the Vulnerable Children’s Resettlment Scheme (VCRS)—Wales. London: Home Office. [Google Scholar]

- House of Lords Library Briefing. 2018. Impact of ‘Hostile Environment’ Policy. Available online: http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/LLN-2018-0064/LLN-2018-0064.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Intke-Hernandez, Minna. 2015. Stay-at-Home Mothers Learning Finnish. In Adult Language Education and Migration: Challenging Agendas in Policy and Practice. Edited by James Simpson and Anne Whiteside. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 119–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kapborg, Inez, and Carina Berterö. 2002. Using an Interpreter in Qualitative Interviews: Does It Threaten Validity? Nursing Enquiry 9: 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Kamran, and Tim McNamara. 2017. Citizenship, Immigration Laws, and Language. In The Routledge Handbook of Migration and Language. Edited by Suresh Canagarajah. London: Routledge, pp. 451–67. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Jones, Marilyn. 2015. Afterword. In Adult Language Education and Migration. Edited by James Simpson and Anne Whiteside. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the High Commission for Human Rights. 2019. Visit to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland—Report of the Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance. Available online: https://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/41/54/Add.2 (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Right to Remain. 2018. Claim Asylum. Available online: https://righttoremain.org.uk/toolkit/claimasylum/ (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Sidaway, Kathryn. 2018. The Effects and Perception of Low-Stakes Exams on the Motivation of Adult Esol Students in the Uk. Language Issues: The ESOL Journal 29: 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, James. 2016. English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL): Language education and migration. In The Routledge Handbook of English Language Teaching. Edited by Graham Hall. Routledge Handbooks in Applied Linguistics. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, James. 2019. Navigating immigration law in a “hostile environment”: Implications for adult migrant language education. In preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Sarah, and Katharine Charsley. 2016. Conceptualising integration: A framework for empirical research, taking marriage migration as a case study. Comparative Migration Studies 4: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturge, Georgina. 2019. Migration Statistics: How Many Asylum Seekers and Refugees are There in the UK? House of Commons Library. Available online: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/insights/migration-statistics-how-many-asylum-seekers-and-refugees-are-there-in-the-uk/ (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Temple, Bogusia, and Rhetta Edwards. 2011. Limited Exchanges: Approaches to Involving People Who Do Not Speak English in Research and Service Development. In Doing Research with Refugees. Edited by Bogusia Temple and Rhetta Moran. Bristol: The Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. 1951. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/1951-refugee-convention.html (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Welsh Government. 2014. ESOL Policy for Wales. Available online: http://gov.wales/docs/dcells/publications/140619-esol-policy-en.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Welsh Government. 2015. Well-Being of Future Generations Act. Available online: https://gweddill.gov.wales/topics/people-and-communities/people/future-generations-act/duty/?lang=en (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Welsh Government. 2017. Adult Learning in Wales. Available online: https://beta.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-08/adult-learning-in-wales.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Welsh Government. 2018a. ESOL Policy for Wales. Available online: https://beta.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-11/english-for-speakers-of-other-languages-esol-policy-for-wales.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Welsh Government. 2018b. Nation of Sanctuary: Refugee and Asylum Seeker Delivery Plan. Available online: https://beta.gov.wales/sites/default/files/consultations/2018-03/180322-nation-of-sanctuary-consultation-v1.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Welsh Government. 2018c. Prosperity for all National Strategy. Available online: https://gov.wales/docs/strategies/170919-prosperity-for-all-en.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Welsh Government. 2019a. Nation of Sanctuary: Refugee and Asylum Seeker Plan. Available online: https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-03/nation-of-sanctuary-refugee-and-asylum-seeker-plan_0.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Welsh Government. 2019b. New Refugee and Asylum Seeker Plan for Wales Launched [Press release]. Available online: https://gov.wales/new-refugee-and-asylum-seeker-plan-wales-launched (accessed on 10 September 2019).

| 1 | Under the 1999 Immigration and Asylum Act. |

| 2 | Under the Wales Act 2017. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chick, M.; Hannagan-Lewis, I. Language Education for Forced Migrants: Governance and Approach. Languages 2019, 4, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030074

Chick M, Hannagan-Lewis I. Language Education for Forced Migrants: Governance and Approach. Languages. 2019; 4(3):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030074

Chicago/Turabian StyleChick, Mike, and Iona Hannagan-Lewis. 2019. "Language Education for Forced Migrants: Governance and Approach" Languages 4, no. 3: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030074

APA StyleChick, M., & Hannagan-Lewis, I. (2019). Language Education for Forced Migrants: Governance and Approach. Languages, 4(3), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030074