Translingual Practices and Reconstruction of Identities in Maghrebi Students in Galicia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodological Considerations3

- Discussion groups, based on the Jigsaw technique (Aronson 1978), in which language trajectories are constructed in a group format;

- The reconstruction of family language biographies based on an activity known as ‘the Language Tree’, in which participates record the languages of their ancestors in a genealogical tree format, together with the languages used in their family environment, both in Galicia and their country of origin;

- Longitudinal interviews;

- A discussion group set up via a WhatsApp chat (Dud@sxlingu@s), providing the respondents with a forum for reflection on the various languages included in their family trajectories;

- A quantitative sociolinguistic survey (Rodríguez Neira et al. 2019).

3. Results of Our Analysis

3.1. Parental Agency in Maintaining the Family Language

- 1.

- INV: ¿Qué lengua o qué lenguas de las que habéis señalado cada uno en su árbol es la más importante?

- 2.

- INV: Para vosotros.

- 3.

- (Todos los alumnos contestan a la vez y no se entiende)

- 4.

- INV: No vamos a hablar así, que cada uno diga una idea ¿vale?

- 5.

- (0.72)

- 6.

- INV: Vamos a empezar por aquí.

- 7.

- SR: Eh, árabe

- 8.

- INV: XXX

- 9.

- (0.52)

- 10.

- INV: ¿Por qué xxx?

- 11.

- SR: Porque es la que más se usa en Marruecos.

- 12.

- CG: xxxx.

- 13.

- INV: Estamos hablando no solo de Marruecos, sino de Marruecos, España, la familia, el barrio, la escuela, todo.

- 14.

- (0.20)

- 15.

- INV: Todo vuestro entorno.

- 16.

- (Niño 3 asienta con la cabeza)

- 17.

- INV: ¿Vale?

- 18.

- (2.03)

- 19.

- INV: ¿Vale? árabe.

- 20.

- (0.65)

- 21.

- SR: Eh, ¿cómo, qué de qué?

- 22.

- INV: ¿Por qué es la más importante para ti?

- 23.

- SR: Porque es la que yo uso y considero más importante.

- 24.

- INV2: ¿Tú la usas?

- 25.

- (0.42)

- 26.

- SR: Sí, xxxx.

- 27.

- (Todos los alumnos se ríen y no se escucha lo que dice el alumno que está interviniendo)

- 28.

- INV: xxxx

- 29.

- INV: ¿Sí?

- 30.

- (1.33)

- 31.

- INV: árabe ¿con la familia, no?

- 32.

- SR: Sí, con la familia, pero xxxx.

- 33.

- INV: Vale, ¿XX?

- 34.

- SM: Dariya.

- 35.

- INV: ¿Dariya también?

- 36.

- (1.21)

- 37.

- INV: ¿Por qué?

- 38.

- (0.60)

- 39.

- SM: Porque es la que nos enseñan nuestros padres y nos la siguen enseñando.

- 40.

- (0.42)

- 41.

- SM: Para

- 42.

- INV: Uhu.

- 43.

- (0.66)

- 44.

- INV: Y ¿pensáis que la vais a transmitir a vuestros hijos también?

- 45.

- SM: Sí.

- 46.

- INV: ¿La tenéis que aprender porque solamente porque la hablas todos los días o porque es algo muy importante y tenéis que mantenerla y luego transmitirla...?

- 47.

- (0.31)

- 48.

- INV: ¿No?

- 49.

- (0.38)

- 50.

- INV: ¿Por qué?

- 51.

- (0.26)

- 52.

- INV: árabe ¿qué pensáis los demás?

- 53.

- CG: Dos.

- 54.

- CR árabe.

- 55.

- INV: árabe.

- 56.

- (0.53)

- 57.

- CG: Yo dos el español y el, y el, el árabe.

- 58.

- CG: Dariya.

- 59.

- INV: Dariya.

- a.

- (0.49)

- 60.

- INV: Son muy importantes, ¿por qué?

- 61.

- CG: ¿Por qué? Porque yo las uso las dos para hablar en casa con los amigos, todo.

- b.

- (0.25)

- 62.

- CG: La familia, el cole.

- 63.

- (0.36)

- 64.

- CG: Es que, es que es la que más uso con todo.

- 65.

- INV2: ¿El gallego no xxxx?

- 66.

- CG: A ver.

- 67.

- (0.82)

- 68.

- CG: En español entra el gallego, pero yo no hablo gallego solo en clase de gallego.

- 69.

- (0.75)

- 70.

- CG: Sabes, yo yo como personalmente yo el gallego no lo uso.

- 71.

- (0.85)

- 72.

- (N5 gesticula con las manos y encoge los hombros)

- 73.

- CG: ¿Sabes?

- 74.

- (2.30)

- 75.

- INV: O sea, en términos de uso crees que el español y el dariya son los más importantes porque los usas más.

- 76.

- CG: Para mí, sí.

- 77.

- INV: Para ti.

- 78.

- (0.19)

- 79.

- INV: Sí, sí, para ti xxx.

- 80.

- (1.30)

- 80.

- CG: Para ti.

- 82.

- (N5 le pone la mano en el hombro a su compañero de al lado mientras lo mira)

- 83.

- INV: ¿Quién, quién quiere hablar, opinar?

- 84.

- CR: Yo.

- 85.

- (0.28)

- 86.

- (N5 señala a N6 con el dedo)

- 87.

- CR: Yo.

- 88.

- INV: xxxx.

- 89.

- CR Yo, dariya.

- 90.

- INV: ¿También?

- 91.

- CR: Sí.

- 92.

- (0.57)

- 93.

- CR: Porque, porque yo soy de una religión que está en ese idioma.

- 94.

- (0.39)

- 95.

- INV: ¿La religión está en este idioma?

- 96.

- (0.66)

- 97.

- INV: ¿Y crees que por ser musulmán tienes que hablar esta lengua?

- 98.

- (0.35)

- 99.

- CR: Hombre, sí.

- 1.

- REA: Which language or languages that you marked on your individual trees are the most important?

- 2.

- REA: To you.

- 3.

- (All the pupils answer at the same time, and therefore, their responses are unintelligible)

- 4.

- REA: Let us not do it that way; each person should put forward their idea, OK?

- 5.

- (0.72)

- 6.

- REA: Let us start with you.

- 7.

- SR: Er, Arabic

- 8.

- REA: XXX

- 9.

- (0.52)

- 10.

- REA: Why xxx?

- 11.

- SR: Because it is the one spoken most in Morocco.

- 12.

- CG: xxxx.

- 13.

- REA: We are not just talking about Morocco, but Morocco, Spain, the family, the neighborhood, school, everywhere.

- 14.

- (0.20)

- 15.

- REA: Your environment as a whole.

- 16.

- (Child 3 nods)

- 17.

- REA: OK?

- 18.

- (2.03)

- 19.

- REA: OK? Arabic.

- 20.

- (0.65)

- 21.

- SR: Eh, like, like what?

- 22.

- REA: Why is it the most important one for you?

- 23.

- SR: Because it is the one I speak, and I consider it to be the most important.

- 24.

- REA2: So, you speak it?

- 25.

- (0.42)

- 26.

- SR: Yes, xxxx.

- 27.

- (All the pupils laugh, and it is impossible to make out what the pupil who is speaking is saying)

- 28.

- REA: xxxx

- 29.

- REA: So?

- 30.

- (1.33)

- 31.

- REA: Arabic, with the family, right?

- 32.

- SR: Yes, with the family, but xxxx.

- 33.

- REA: OK, ¿XX?

- 34.

- SM: Dariya.

- 35.

- REA: Dariya as well?

- 36.

- (1.21)

- 37.

- REA: Why?

- 38.

- (0.60)

- 39.

- SM: Because that is the one our parents taught us, and they still do.

- 40.

- (0.42)

- 41.

- SM: For

- 42.

- REA: Uh-huh.

- 43.

- (0.66)

- 44.

- REA: And do you think you will pass it on to your kids as well?

- 45.

- SM: Yes.

- 46.

- REA: Do you have to learn it just because you speak it every day or because it is important and something you should maintain and then pass on …?

- 47.

- (0.31)

- 48.

- REA: Is that not the case?

- 49.

- (0.38)

- 50.

- REA: Why?

- 51.

- (0.26)

- 52.

- REA: Arabic. What do the rest of you think?

- 53.

- CG: Two.

- 54.

- CR Arabic.

- 55.

- REA: Arabic.

- 56.

- (0.53)

- 57.

- CG: In my case two: Spanish and, and Arabic.

- 58.

- CG: Dariya.

- 59.

- REA: Dariya.

- a.

- (0.49)

- 60.

- REA: Why are they so important?

- 61.

- CG: Why? Because I speak both languages at home, with my friends, everyone.

- b.

- (0.25)

- 62.

- CG: Family, school.

- 63.

- (0.36)

- 64.

- CG: And it is like the one I use most, for everything.

- 65.

- REA2: Don’t you speak Galician xxxx?

- 66.

- CG: Well.

- 67.

- (0.82)

- 68.

- CG: Galician and Spanish go together, but I do not just speak Galician in Galician language lessons.

- 69.

- (0.75)

- 70.

- CG: You know, personally, I, I do not speak Galician.

- 71.

- (0.85)

- 72.

- (Child 5 gesticulates and shrugs his shoulders)

- 73.

- CG: You know what I mean?

- 74.

- (2.30)

- 75

- REA: In other words, in terms of usage, you think that Spanish and Dariya are more important because you use them more.

- 76.

- CG: In my case, that is true.

- 77.

- REA: In your case.

- 78.

- (0.19)

- 79.

- REA: Yes, yes, in your case xxx.

- 80.

- (1.30)

- 81.

- CG: In your case.

- 82.

- (N5 places his hand on the shoulder of the classmate sitting next to him and turns to look at him)

- 83.

- REA: So, who would like to say something and give their opinion?

- 84.

- CR: Me.

- 85.

- (0.28)

- 86.

- (Child 5 points to Child 6)

- 87.

- CR: Me.

- 88.

- REA: xxxx.

- 89.

- CR In my case, Dariya.

- 90.

- REA: So, you agree?

- 91.

- CR: Yes.

- 92.

- (0.57)

- 93.

- CR: Because that is the language of my religion.

- 94.

- (0.39)

- 95.

- REA: Religion is in that language?

- 96.

- (0.66)

- 97.

- REA: So, you think that because you are a Muslim, you have to speak that language?

- 98.

- (0.35)

- 99.

- CR: Basically, yes.]

3.2. Adolescent Agency in Handling Family Multilingualism

- 1.

- INV: A VER FTM (Voz más alta para propiciar el turno de participación)

- 2.

- FTM: Con mis padres hablo en árabe

- 3.

- INV: ¿En árabe marroquí?

- 4.

- FTM: Sí

- 5.

- (…)

- 6.

- FTM: Con con mis hermanos en español

- 7.

- (…)

- 8.

- INV: ¿Siempre en español con tus hermanos?

- 9.

- (…)

- 10.

- FTM: No siempre, a veces

- 11.

- MART: [xxx]

- 12.

- FTM: Con mis vecinos en gallego

- 13.

- (…)

- 14.

- FTM: ¡Ei! [Pausa] Con los amigos, en castellano

- 1.

- [REA: SO, LET US SEE FTM (Speaks louder to encourage turn taking)

- 2.

- FTM: I speak to my parents in Arabic.

- 3.

- REA: In Moroccan Arabic?

- 4.

- FTM: Yes

- 5.

- (…)

- 6.

- FTM: And I speak to my brothers and sisters in Spanish.

- 7.

- (…)

- 8.

- REA: Do you always speak to your brothers and sisters in Spanish?

- 9.

- (…)

- 10.

- FTM: Not always, sometimes.

- 11.

- MART: [ xxx

- 12.

- FTM: I speak Galician to the neighbors.

- 13.

- (…)

- 14.

- FTM: Hey! [Pause] And Spanish to my mates.]

- 1.

- CG: Eh os voy a decir esto. Mi abuelo materno habla español y gallego.

- 2.

- CG: Mi abuela materna habla español y gallego. Mi abuela paterna habla árabe y dariya.

- 3.

- CG: Mi abuelo paterno habla árabe, francés y dariya. Mi madre habla español y gallego, y marroquí (…) ah no mucho a ver.

- 4.

- CG: Mi padre español, gallego, francés, dariya, chleuh y tamazight.

- 5.

- CG:Y yo hablo español, gallego, francés, inglés, árabe y chleuh..poco.

- 6.

- CG:Y mis hermanos español la mayoría, árabe, francés, inglés y el gallego.

- 1.

- [CG: Hey, let me say this. My maternal grandfather speaks Spanish and Galician.

- 2.

- CG: My maternal grandmother speaks Spanish and Galician. My paternal grandmother speaks Arabic and Dariya. My paternal grandfather speaks Arabic, French, and Dariya.

- 3.

- CG: My mother speaks Spanish and Galician, and Morocco (…) but only a bit, you know.

- 4.

- CG: My father, Spanish, Galician, French, Dariya, Shelha, and Tashelhyt.

- 5.

- CG: As for me, I can speak Spanish, Galician, French, English, Arabic, and a bit of Shelha.

- 6.

- CG: And my brothers and sisters Spanish, most of them, Arabic, French, English, and Galician.]

3.3. Adolescent Agency in Handling New Forms of Language Resistance in Digital Discourse

- 1.

- Inv: ¿Cuándo escribís dariya en el chat con alfabeto latino?

- 2.

- ¿cómo lo hacéis de izquierda a derecha o de derecha a izquierda?

- 3.

- Ou: NORMAL

- 4.

- Inv: ¿Qué es normal?

- 5.

- (Se inicia una discusión sobre la dirección en la que escriben. Acompañan con gestos [tienen que pensarlo)

- 6.

- Fd: Cuando escribimos en alfabeto árabe de derecha a izquierda y en dariya en el chat

- 7.

- con alfabeto latino y números de izquierda a derecha.

- 8.

- In: ¿Quién os enseñó a escribir así?, ¿aprendistéis aquí?

- 9.

- Ou, Mr, Fd [al mismo tiempo] Nos enseñaron en Marruecos a usar el alfabeto latino

- 10.

- con los números

- 11.

- (…)

- 12.

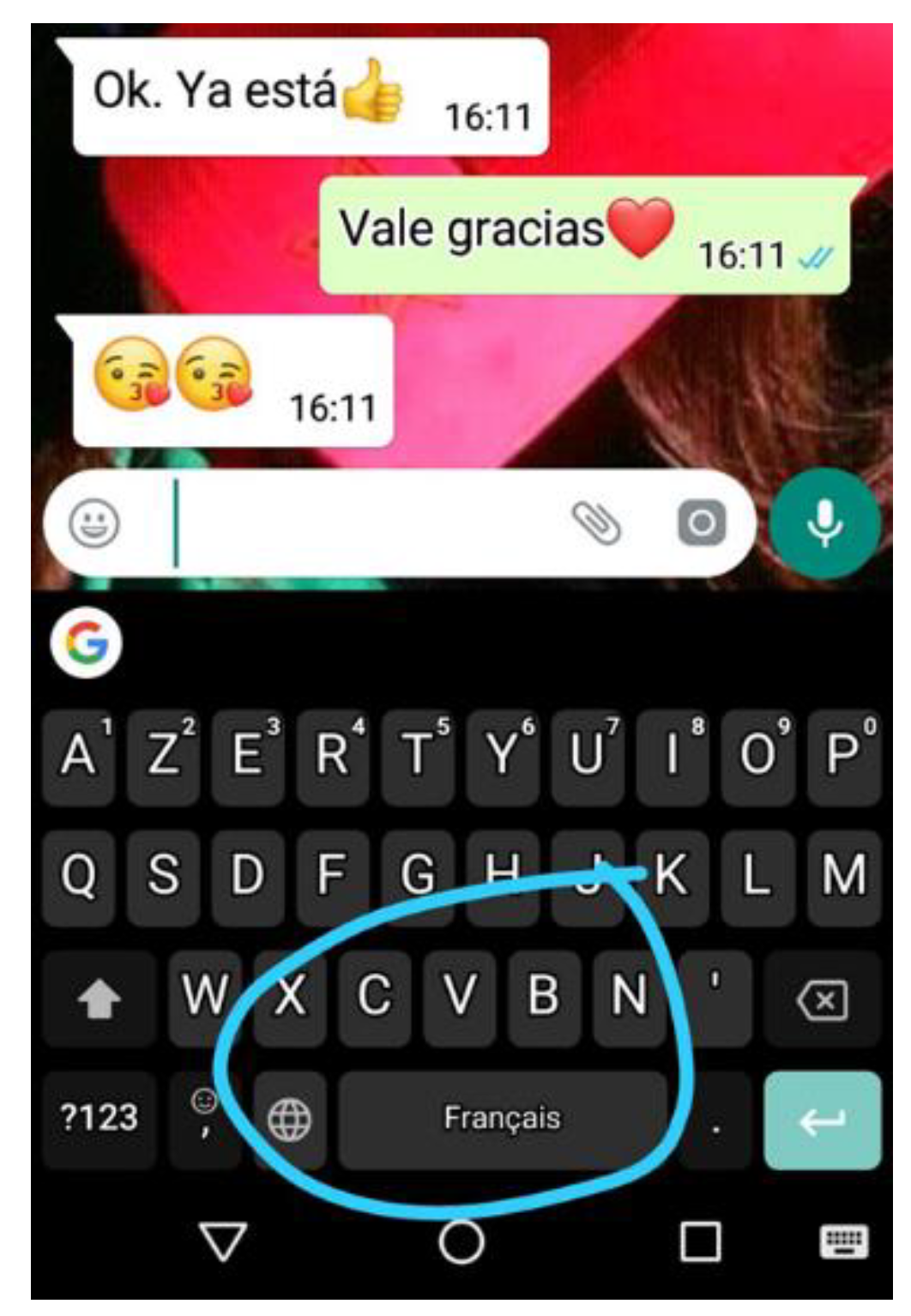

- MR: Por ejemplo yo tuve que aprender los números en el teclado francés (muestran la pantalla del teléfono que reproducimos en la figura 1)

- 13.

- y además lo que significaba por ejemplo: cv que es ça va

- 14.

- In: ¿Hace tres años en Marruecos utilizabas WhatsApp?

- 15.

- Ou: Sí, sí y allí ya cambió

- 16.

- In: ¿Lo usáis igual que en Marruecos?

- 17.

- Al mismo tiempo varias: Sí, no xxx (Dudan)

- 18.

- Inv: ¿Estáis en redes con chicos y chicas de Marruecos y otros lugares de Europa?

- 19.

- Ou, Mr: Sí sí, de diferentes lugares

- 1.

- [Rea: When you use the Latin alphabet to write in Dariya on the chat?

- 2.

- How do you do it? From left to right or from right to left?

- 3.

- Ou: NORMAL

- 4.

- Rea: What does normal mean?

- 5.

- (A discussion starts up regarding the direction in which they write. This is accompanied by gestures, and they have to visualize it)

- 6.

- Fd: When we use the Arabic alphabet from right to left and from left to right when we

- 7.

- use Dariya in the Latin alphabet on the chat.

- 8.

- Rea: Who taught you how to write like that? Did you learn that here?

- 9.

- Ou, Mr, Fd [all at the same time]: We learned to use the Latin alphabet with numbers

- 10.

- in Morocco

- 11.

- (…)

- 12.

- Mr: For instance, I had to learn how to use numbers with the French keyboard [they show the screen of the phone that we reproduce in Figure 1] as well as what they meant, I mean like ‘cv’ is ça va.

- 13.

- Rea: Did you use WhatsApp in Morocco three years ago?

- 14.

- Ou, Mr, Fd: Yes, yes, it had already changed there

- 15.

- Rea: Do you use it in the same way as in Morocco?

- 16.

- Several members speak at the same time: Yes, No xxx (They are unsure)

- 17.

- Rea: Are you in contact via social media with young people from Morocco and other parts of Europe?

- 18.

- Ou, Mr: Yes, yes, from different places]

Figure 3 (translation): The text in Moroccan Arabic and French “DimaMaroc” translates to “Always Morocco”.

“[T]ranslanguaging space is particularly relevant to multilinguals not only because of their capacity to use multiple linguistic resources to form and transform their own lives, but also because the space they create through their multilingual practices, or translanguaging, has its own transformative power informal. It is as space where the process of what Bhabha (1994) calls “cultural translation” between traditions takes place; it is not a space where different identities, values and practices simply co-exist, but combine together to generate new identities, values and practices”:

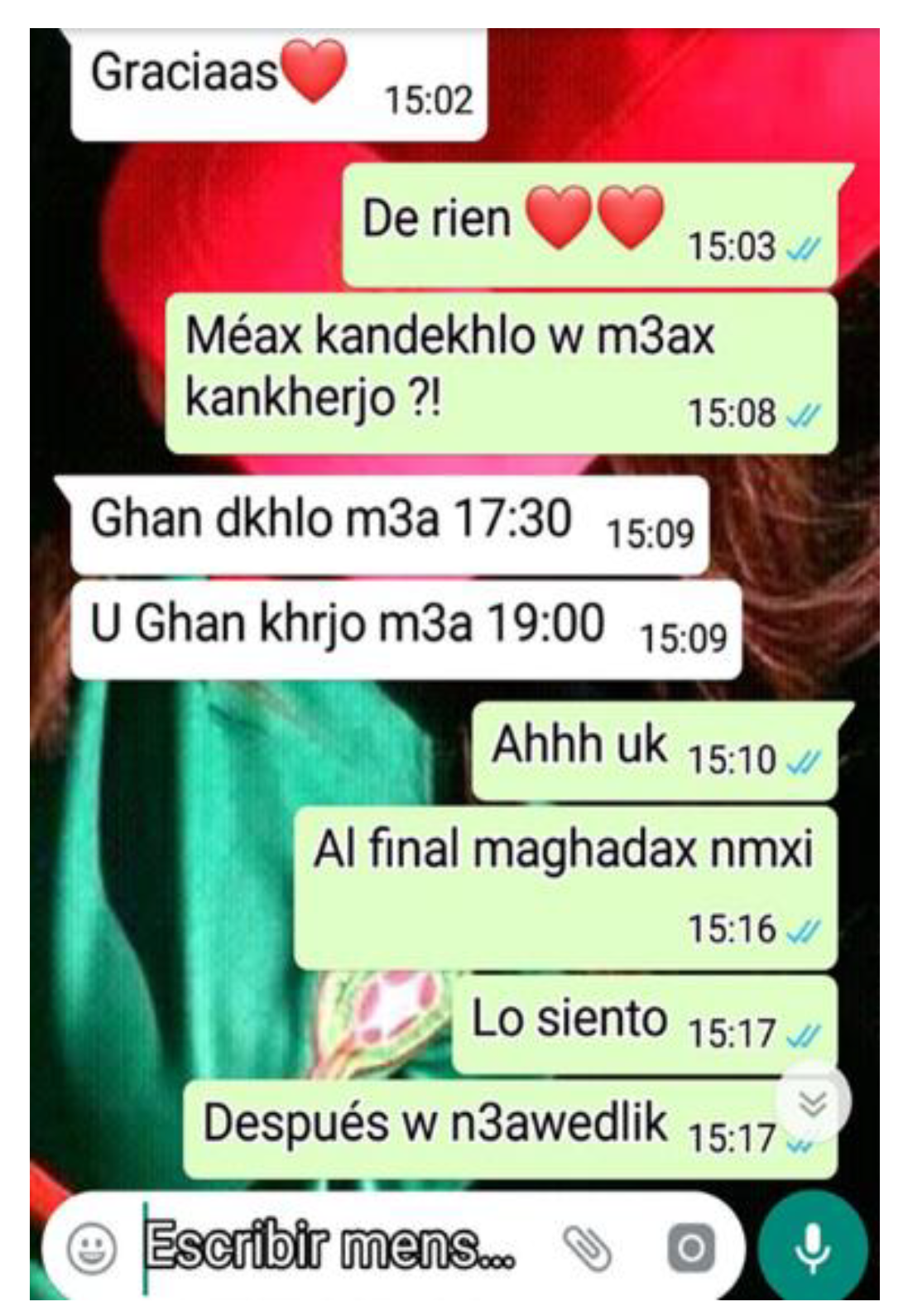

Figure 4 (translation): WhatsApp chatThanksNot at all!What time do we start and finish?We start at 17:30We finish 19:00Ah. OK.I’m not going in the endSorry about thatI tell you later

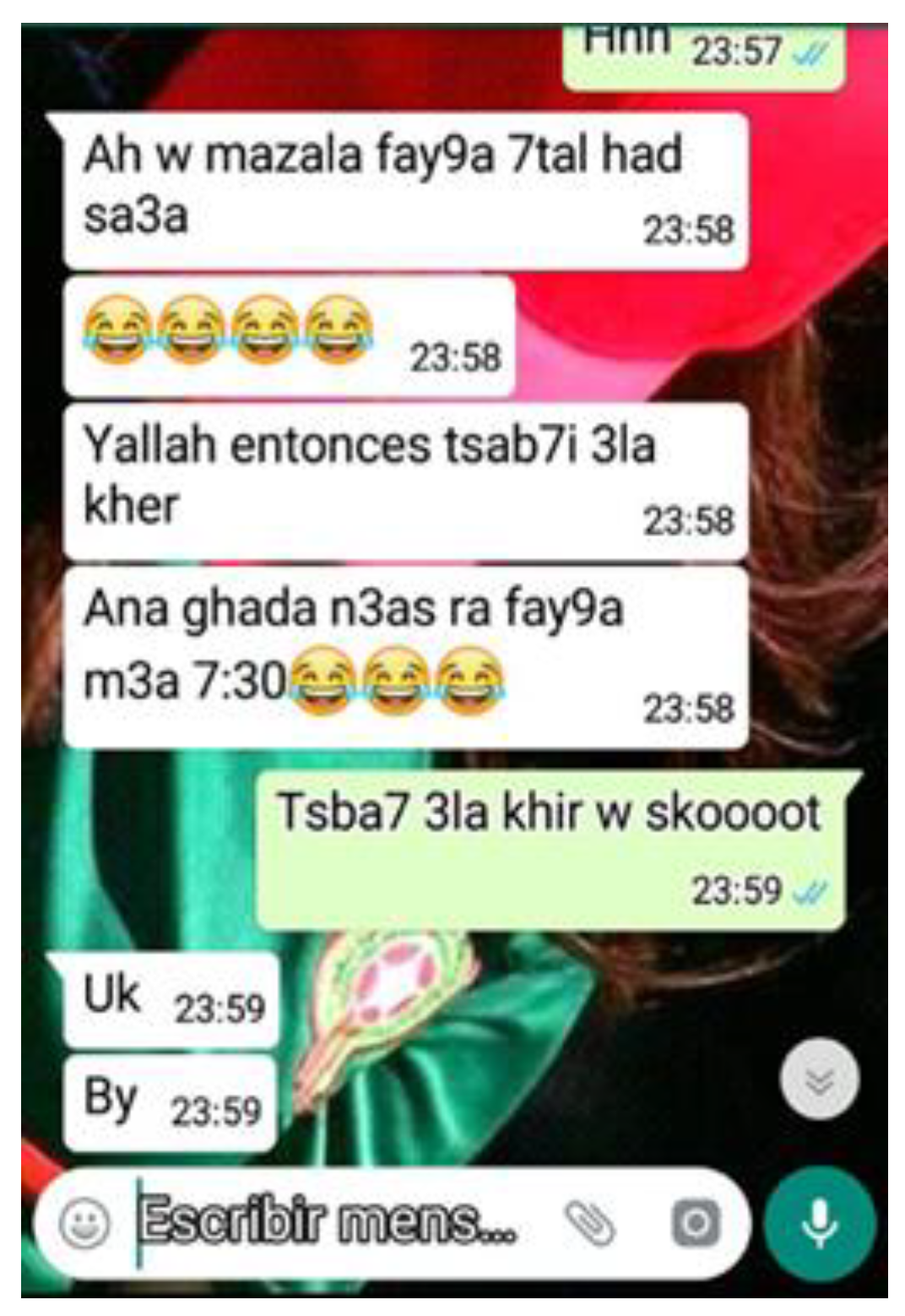

Figure 5 (translation): WhatsApp chat.Ah, so you’re still awake this late.Sleep well thenI’m going to sleep now; tomorrow I’ve got to wake up at 7:30So stop talking and sleep well.OkBye

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AIMC. 2019. Audiencia de Internet en el EGM. Abril 2018/marzo 2019. Madrid: Asociación para la Investigación en Medios de Comunicación, Available online: https://www.aimc.es/egm/audiencia-internet-egm/ (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Alcántara, Manuel. 2014. Las unidades discursivas en los mensajes instantáneos de wasap. Estudios de Lingüística del Español 35: 223–42. [Google Scholar]

- Allehaiby, Wid H. 2013. Arabizi: An Analysis of the Romanization of the Arabic Script from a Sociolinguistic Perspective. Arab World English Journal 4: 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, Elliot. 1978. The Jigsaw Classroom. Beverly Hills: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, Mijail. 1989. Las formas del tiempo y del cronotopo en la novela. Ensayos sobre Poética Histórica. In Teoría y estética de la novela. Translated by Helena Kriukova, and Vicente Cazzarra. Madrid: Taurus, pp. 237–410. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corona, Victor, Luci Nussbaum, and Virginia Unamuno. 2013. The emergence of new linguistic repertoires among Barcelona’s youth of Latin American Origin. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 16: 182–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Normand. 1990. Critical Language Awareness. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Normand. 1999. Global capitalism and critical awareness of language. Language Awareness 8: 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Ofelia. 2008. Multilingual language awareness and teacher education. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2nd ed. Edited by Jasone Cenoz and Nancy Hornberger. Berlin: Springer, vol. 6, pp. 385–400. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia. 2009. Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st century. In Multilingual Education for Social Justice: Globalising the Local. Edited by Ajit Mohanty Minati Panda, Robert Phillipson and Tove Skutnabb-Kangas. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan (former Orient Longman), pp. 128–45. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, Kate Seltzer, and Daria Witt. 2018. Disrupting linguistic inequalities in US urban classrooms: The role of translanguaging. In The Multilingual Edge of Education. Edited by Piet Van Avermaet, Stef Slembrouck, Koen Van Gorp, Sven Sierens and Katrija Marijns. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self Identity: Self and Identity in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1981. Forms of Talk. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnizo, Luis Eduardo. 1997. The Emergence of a Transnational Social Formation and the Mirage of Return Migration among Dominican Transmigrants. Identities 4: 281–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumperz, John. 1982. Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Eric. 1984. Awareness of Language: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Eric. 1992. Awareness of language/knowledge about language in the curriculum of England and Wales. An historical note on twenty years of curricular debate. Language Awareness 1: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, Monica. 2002. Éléments d’une Sociolinguitique Critique. Paris: Didier. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunter. 2010. Multimodality. A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, Gene. 1996. On the Place of Linguistic Resources in the Organization of Talk-in-Interaction: ‘Second Person’ Reference in Multi-Party Conversation. Pragmatics 6: 281–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llompart, Julia. 2016. Enseñar lengua en la superdiversidad: De la realidad sociolingüística a las prácticas de aula. Signo y Seña 29: 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mancera, Ana. 2016. Usos lingüísticos alejados del español normativo como seña de identidad en las redes sociales. Bulletin of Spanish Studies 93: 1469–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancera, Ana, and Ana Pano. 2013. El español coloquial en las redes sociales. Madrid: Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Gascueña, Rosa. 2016. La conversación guasap. Soprag 4: 108–34. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Rojo, Luisa. 2010. Constructing Inequality in Multilingual Classrooms. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Milroy, Lesley. 1980. Language and Social Networks. Oxford: Blackwel. [Google Scholar]

- Moustaoui Srhir, Adil. 2016. Tú serás el responsable ante Dios el día del juicio si no le enseñas árabe (a tu hijo-a): lengua árabe, identidad y vitalidad etnolingüística en un grupo de marroquíes en Madrid. Lengua y Migración 8: 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Moustaoui Srhir, Adil. 2019a. Política lingüística en familias de origen marroquí: ideologías, prácticas y desafíos. In Transmissions. Estudis sobre la trasmissió lingüística. Edited by Mónica Barrieras and Carla Ferrerós. Vic: Editorial Eumo, pp. 179–210. [Google Scholar]

- Moustaoui Srhir, Adil. 2019b. Making Children Multilingual: Language Policy and Parental in Transnational and Multilingual Moroccan Families in Spain. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, Paul, and Jos Swanenber. 2012. Super-diversity in the margins? Youth language in North Brabant, The Netherlands. Sociolinguistic Studies 6: 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostergaard Nielsen, Eva. 2003. The Politics of Migrants: Transnational Political Practices. International Migration Review 37: 760–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereiro, Carmen, Gabriela Prego, and Luz Zas. 2017. Traxectorias lingüísticas de mulleres marroquíes en Galicia. In Muller inmigrante, Lingua e sociedade. Edited by LauraRodríguez Salgado and Iria Vázquez Silva. Vigo: Galaxia, pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Prego Vázquez, Gabriela, and Luz Zas Varela. 2015. Identidades en los márgenes de la superdiversidad: prácticas comunicativas y escalas sociolingüísticas en los nuevos espacios educativos multilingües en Galicia. Discurso y Sociedad 9: 165–96. [Google Scholar]

- Prego Vázquez, Gabriela, and Luz Zas Varela. 2018. Paisaje lingüístico. Un recurso TIC, TAC, TEP para el aula. Lingue Linguaggi 25: 277–95. [Google Scholar]

- Prego Vázquez, Gabriela, and Luz Zas Varela. 2019. Unvoicing practices and the scaling (de)legitimization process of linguistic ‘mudes’ in classroom interaction in Galicia (Spain). International Journal of the Sociology of Language 257: 77–107. [Google Scholar]

- Rampton, Ben. 1995. Language crossing and the problematisation of ethnicity and socialisation. Pragmatics 5: 485–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Neira, Modesto, Gabriela Prego Vázquez, and Luz Zas Varela. 2019. Encuesta sociolingüística para las nuevas realidades multilingües en los centros educativos: Datos cuantitativos y cualitativos cara a cara. Unpublished manuscript. May 29. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, Michael. 1976. Shifters, Linguistic Categories and Cultural descriptions. In Meaning in Anthropology. Edited by Keith H. Basso and Henry A. Selby. Alburquerque: University of New Mexico, pp. 11–56. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Cano, Esteban, Santiago Mengual-Andrés, and Rosabel Roig-Vila. 2015. Análisis lexicométrico de la especificidad de la escritura digital del adolescente en Whatsapp. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada (RLA) 53: 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2007. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies 30: 1024–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xuan, Max Spotti, Kasper Juffermans, Leoni Cornips, Sjaak Kroon, and Jan Blommaert. 2014. Globalization in the margins: Toward a re-evaluation of language and mobility. Applied Linguistics Review 5: 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Li. 2011. Moment Analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics 43: 1222–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Li. 2018. Translanguagins as a Practical Theory of Language. Applied Linguistics 39: 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, Etienne. 2001. Comunidades de práctica: aprendizaje, significado e identidad. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Zas Varela, Luz, and Gabriela Prego Vázquez. 2018. A view of Linguistic Landscapes for an Ethical and Critical Ed Srhirucation. In Galician Migrations: A Case of Emerging Super-Diversity. Edited by Renée DePalma and Antía Pérez-Caramés. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 249–64. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Spanish and Galician are co-official languages in Galicia. |

| 2 | The sociolinguistic survey universe included all pupils enrolled in the municipality’s secondary and baccalaureate schools. We are currently analyzing the data collected. |

| 3 | All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. |

| 4 | Dariya is the term commonly used to refer to Moroccan and Algerian Arabic. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moustaoui Srhir, A.; Prego Vázquez, G.; Zas Varela, L. Translingual Practices and Reconstruction of Identities in Maghrebi Students in Galicia. Languages 2019, 4, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030063

Moustaoui Srhir A, Prego Vázquez G, Zas Varela L. Translingual Practices and Reconstruction of Identities in Maghrebi Students in Galicia. Languages. 2019; 4(3):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030063

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoustaoui Srhir, Adil, Gabriela Prego Vázquez, and Luz Zas Varela. 2019. "Translingual Practices and Reconstruction of Identities in Maghrebi Students in Galicia" Languages 4, no. 3: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030063

APA StyleMoustaoui Srhir, A., Prego Vázquez, G., & Zas Varela, L. (2019). Translingual Practices and Reconstruction of Identities in Maghrebi Students in Galicia. Languages, 4(3), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030063