3.1.1. Top-Down Signs

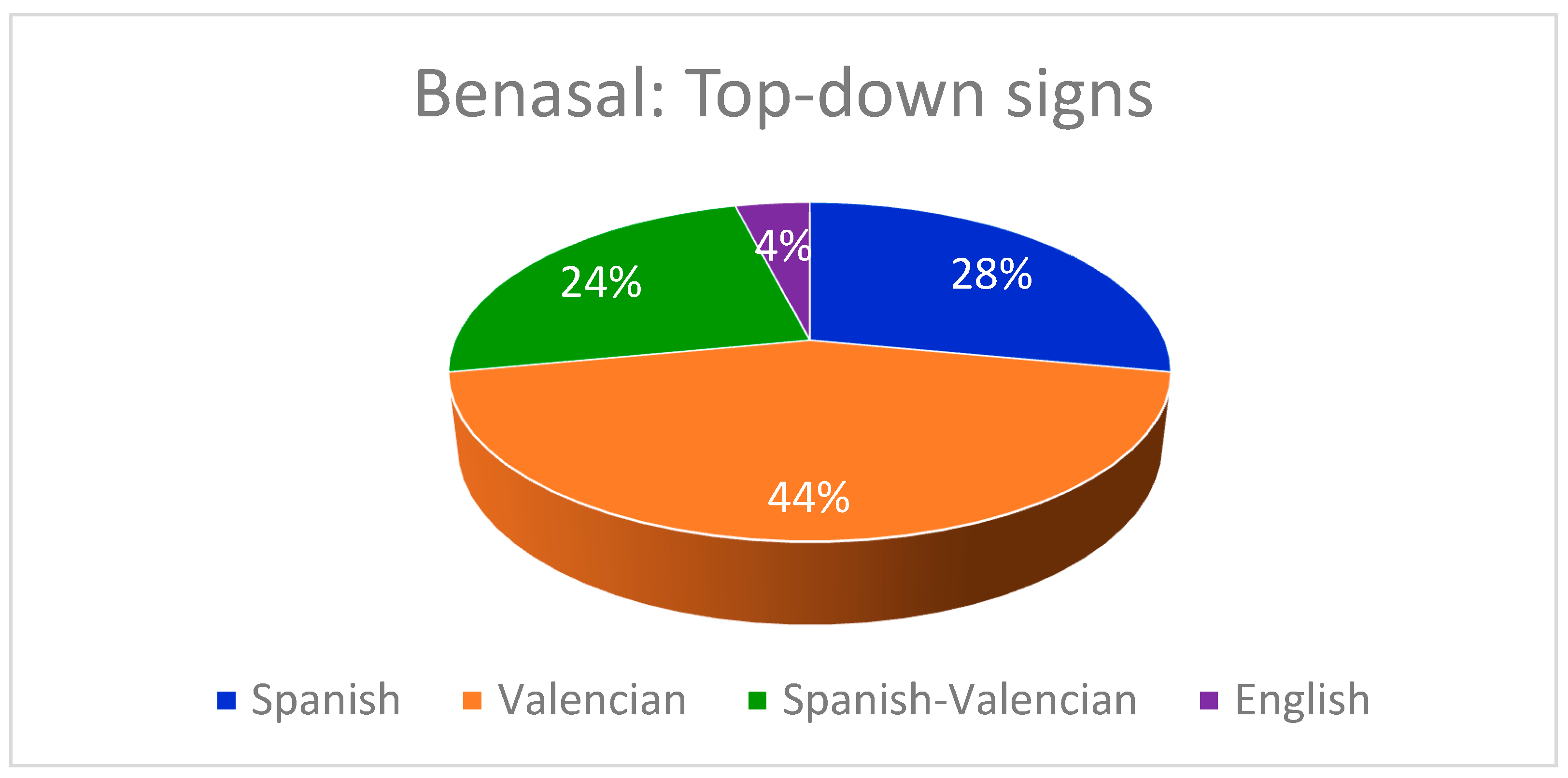

Concerning Benasal, nearly 72% of top-down signs are monolingual, either in Valencian or in Spanish. They are unequally spread over the village. As can be observed in cultural and religious buildings, the frequency of Valencian (44%) in monolingual signs is higher than that of Spanish (28%) (

Figure 1).

Clear examples in Valencian include religious and historical buildings such as chapels (e.g., Capella de la Puríssima) and castles (e.g.,

Castell de la Mola ‘Mola’s castle’), respectively (

Figure 2 and

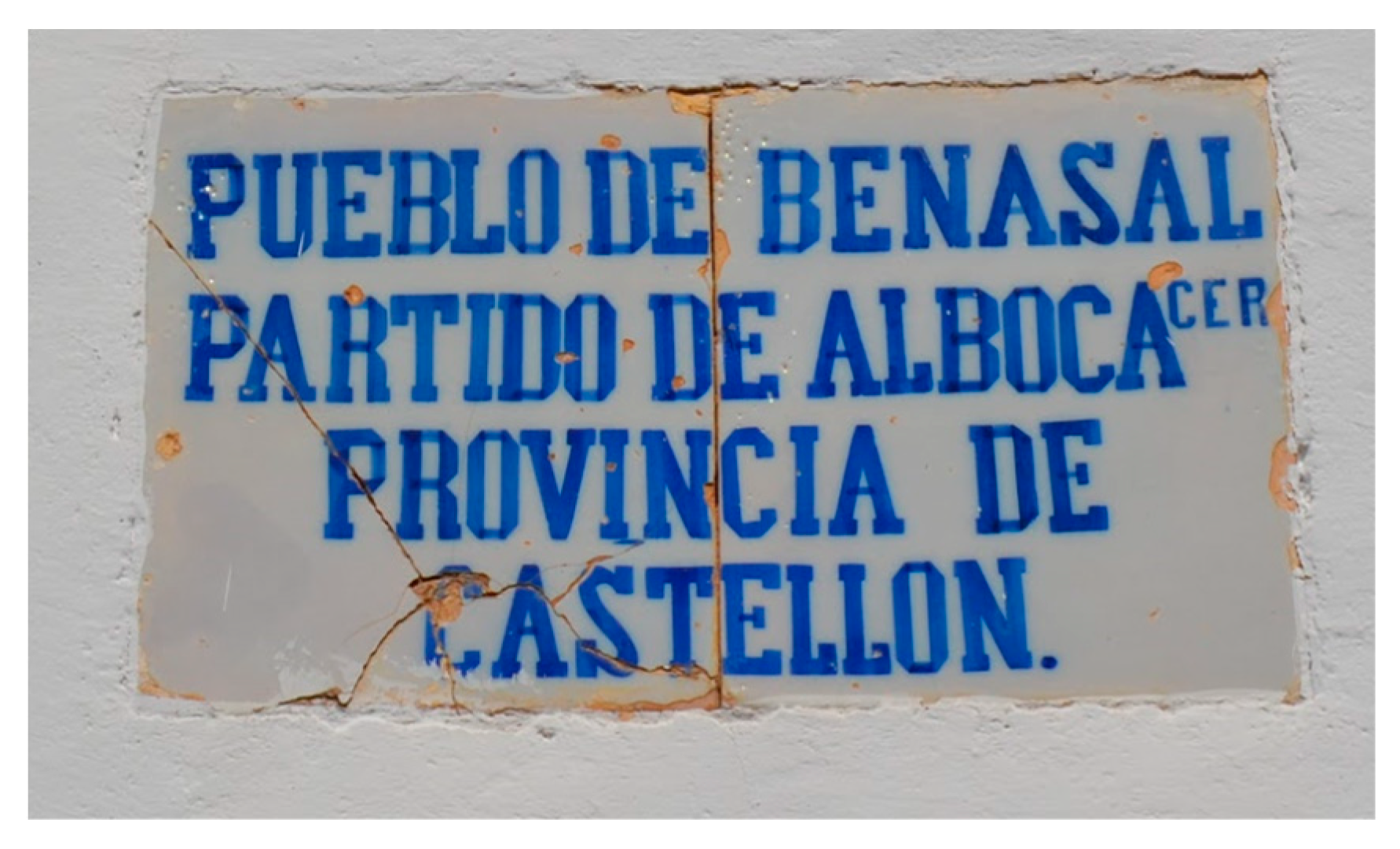

Figure 3). On the contrary, monolingual signs in Spanish involve its well-known spa (

Figure 4) and other historical signs (

Figure 5). In some cases, tourists and locals are provided with a detailed explanation of the sites.

The different linguistic policies that have been implemented since the 20th century have had an impact on the linguistic landscape of Benasal. When it comes to governmental signs, monolingual and bilingual street names were identified (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

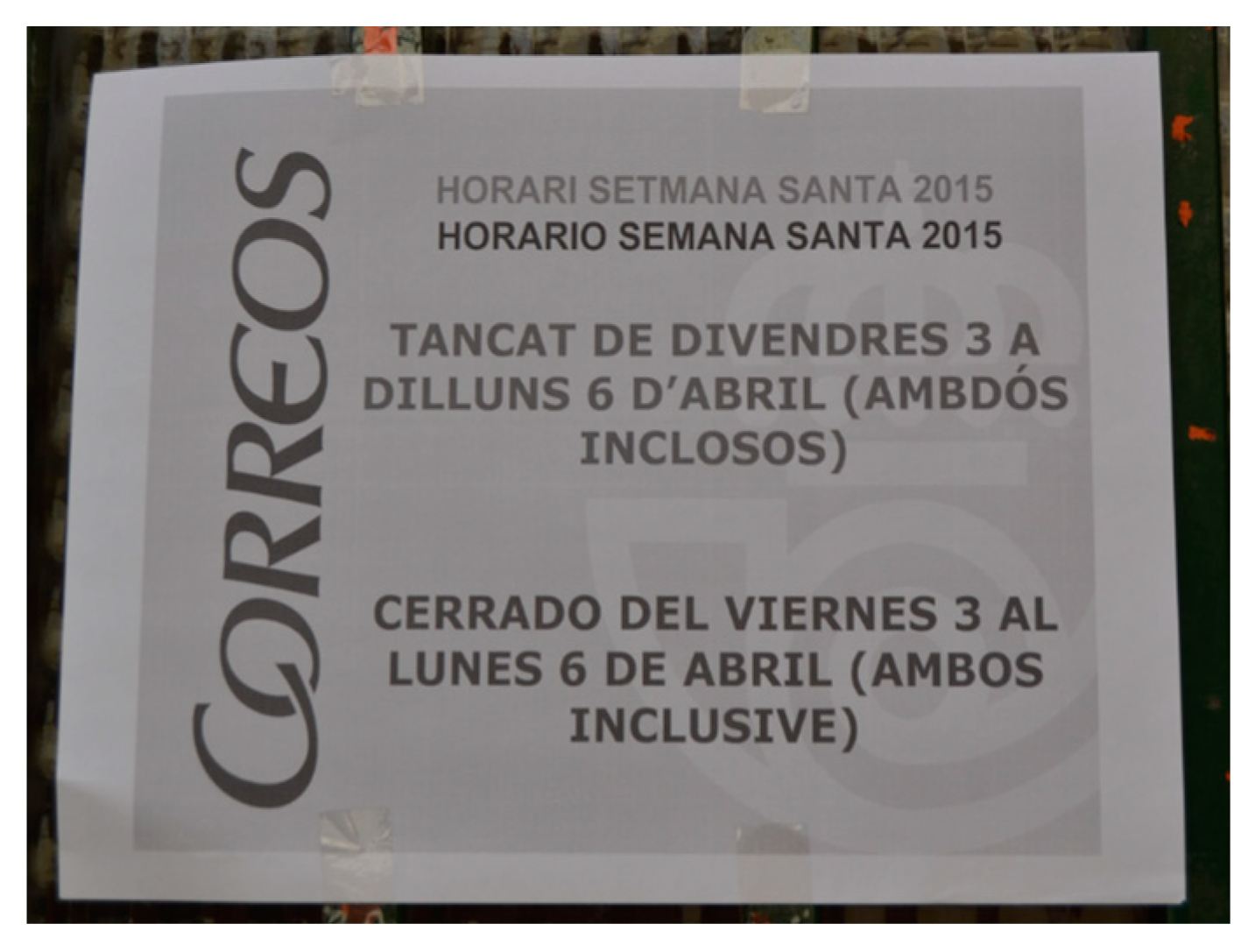

As can be seen above, the number of languages in bilingual signs (24%) is limited to Spanish and Valencian. Thus, the dominant language may vary depending on the time these governmental signs were issued. Evidence can be found in street names, plastic recycling containers (

Figure 9), as well as in the Spanish postal service sign (i.e.,

Correos ‘post office service’) (

Figure 10).

For most of the 20th century, the first linguistic policies promoted the use of Spanish (

Figure 2). Towards the end of the 20th century the regional government regulated the languages included in bilingual signs.

Figure 3 shows the power of Spanish over Valencian as it is the first language appearing on the top of the sign, whereas the opposite occurs in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. These latter seem to be more recent signs, as Valencian is the first language used in an attempt to preserve the village’s local identity. At the beginning of the 21st century, there was a trend to foster the use of Valencian as the main language within that linguistic community. Despite this heterogeneous use of languages, it can be inferred that comprehension is not hindered.

Multilingual signs containing Spanish, Valencian, and English could not be found. So far, the English language is used once, as can be seen in the Tourist Info sign below (

Figure 11). The main reasons for this have to do with a generational gap and tourists’ origins. The proportion of elderly living in this village who did not have the opportunity to learn a foreign language is higher than the proportion of young people. In addition, tourism is primarily national and regional.

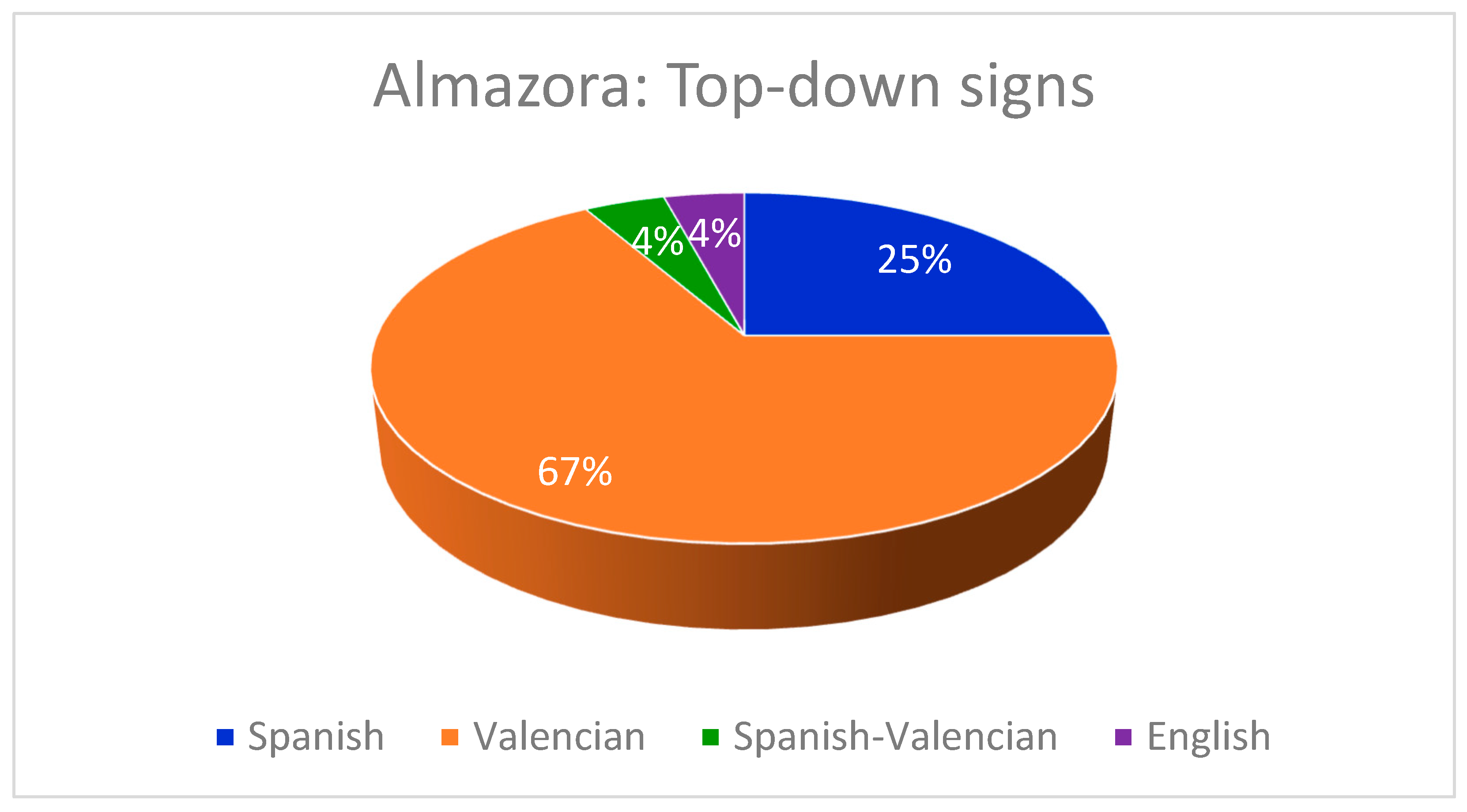

Focusing on Almazora, the vast majority of top-down signs are monolingual (92%) (

Figure 12). Cultural, medical, and governmental monolingual signs show the overwhelming use of the Valencian language in this town (67%). Public spaces including the central market, a local infant school, a hermitage path, and a museum, among others, are all signed in Valencian.

The regional legislation of the Valencian Community states that Valencian-speaking areas should implement linguistic policies that boost exposure to the minority language. This initiative is key to making Valencian (67%) more visible than Spanish (25%). Such monolingual signs include traffic and medical signs that can be observed as a combination of signs. Clear examples involve an outpatient clinic where monolingual signs in Spanish and Valencian can be observed. More specifically, the language employed in the official name of this medical building is Valencian (

Figure 13) rather than Spanish. However, Spanish is used to provide patients with general information of the healthcare fields offered in this area (

Figure 14). In this sense, similar signs that aim at generating bilingual experiences are spread throughout the town.

Contrary to all expectations, the distribution of bilingual and multilingual signs is barely noticeable. As in Benasal, bilingual signs (4%) correspond to street names regulated by the town council, where Valencian is the dominant language (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16). Even though there are no official signs where Spanish or Valencian are combined with other foreign languages, English is displayed in the monolingual Tourist Info sign.

Even though the population of the city by and large has Spanish as its mother tongue, policies have been developed to include the minority language. In the centre of Valencia, approximately 55% of the signs are monolingual (

Figure 17). There seems to be a balance in the use of Spanish-only (22%) and Valencian-only (33%) items. Although both languages are co-official, Valencian is still the preferred language to preserve the identity of the city.

Both languages can be found in historical, religious, and governmental signs. For instance, Valencian is the language displayed in the archaeological centre (

Figure 18). By contrast, Spanish can be seen in the traders’ market, which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site (

Figure 19).

The distribution of bilingual signs in Valencia (11%) is higher than in Almazora. As the centre of Valencia is an eminent tourist area, languages other than Spanish and Valencian are used, particularly English. Hence, it is possible to find bilingual signs combining Spanish and English, and Valencian and English. The sign in

Figure 20 is predominantly for national and international tourists. The font size and colour are the same for both languages; however, Spanish seems to be the more powerful language as it is on the top.

Figure 21 shows a governmental sign in Valencian and English. As can be observed, this is a combination of two signs. The sign on the top has to do with the name of the organisation, but the focus of this picture is on the sign below, where English is the first language appearing. It seems to be addressed to locals and international individuals who work with these languages on a regular basis, especially because it is a regional institution.

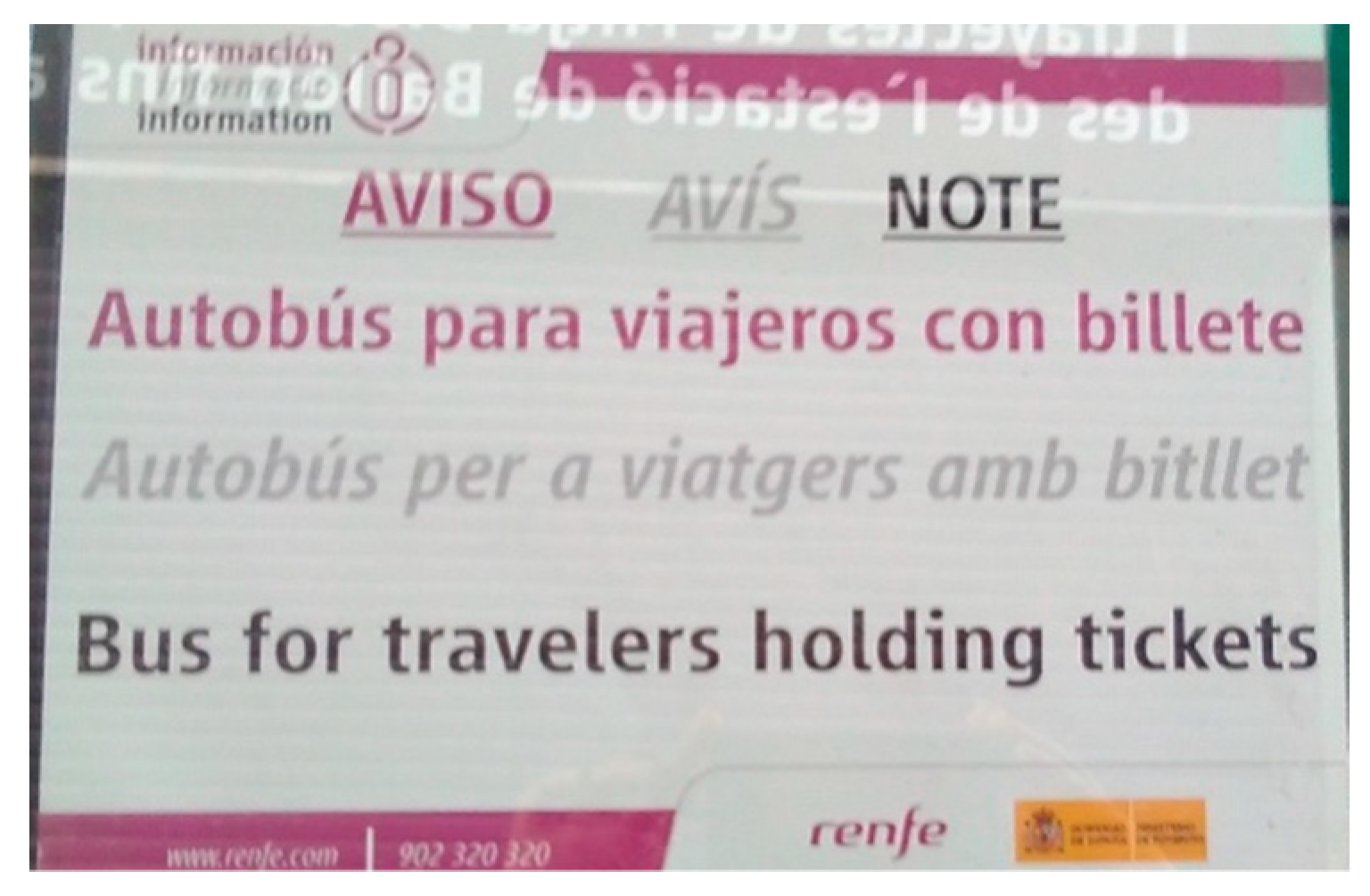

Multilingualism (30%) in Valencia involves the use of Spanish, Valencian, and English (24%). The power relations established suggest that Spanish is the dominant language as it is the first language employed to address locals and tourists (

Figure 22). The inclusion of the minority language involves the use of italics and a light colour, which makes it difficult to read. However, even though English is the third language, it can be read without difficulty.

Linguistic diversity is also determined by the presence of other international languages in multilingual signs (6%).

Figure 23 below shows a wide range of languages including Spanish, Valencian, English, French, Italian, and German. The inclusion of these languages may be related to the main nationalities of the tourists who visit Valencia. The first three languages have the same font size, whereas the font size of the rest of the languages seems to be smaller.

3.1.2. Bottom-Up

Regarding bottom-up signs, clear differences can be found in terms of bilingual and multilingual patterns. In Benasal, a total of 67% of bottom-up signs are monolingual whilst the remaining 33% are bilingual signs (

Figure 24).

Nonofficial signs in Benasal are characterised by the predominance of Spanish-only items (50%). The presence of Spanish in the private sector does not only have to do with the establishment of international companies but also with the opening of businesses that took place during the second half of the 20th century. This is the case of bakeries and bank offices whose brand name is in Spanish (

Figure 25 and

Figure 26). Interestingly, the role of the Valencian language in the private sector is not as frequent as expected (17%).

Bilingual signs are addressed to potential customers. Hence, local businesses try to develop appropriate communication strategies by addressing individuals in Spanish and Valencian. In

Figure 27 and

Figure 28 there is no doubt that Valencian is the most relevant language, as it highlighted in bold, whereas its translation in Spanish may appear in italics and different colours.

Unlike in Benasal, there is no considerable differences in the use of Valencian-only (27%) and Spanish-only (23%) signs in Almazora (

Figure 29). Valencian patterns are found in a variety of areas, such as architecture, podiatry, butchery, haberdashery, bakeries, and language academies, among others. Similarly, Spanish items can be identified in dentists, cafés, hairdressers, and butcheries.

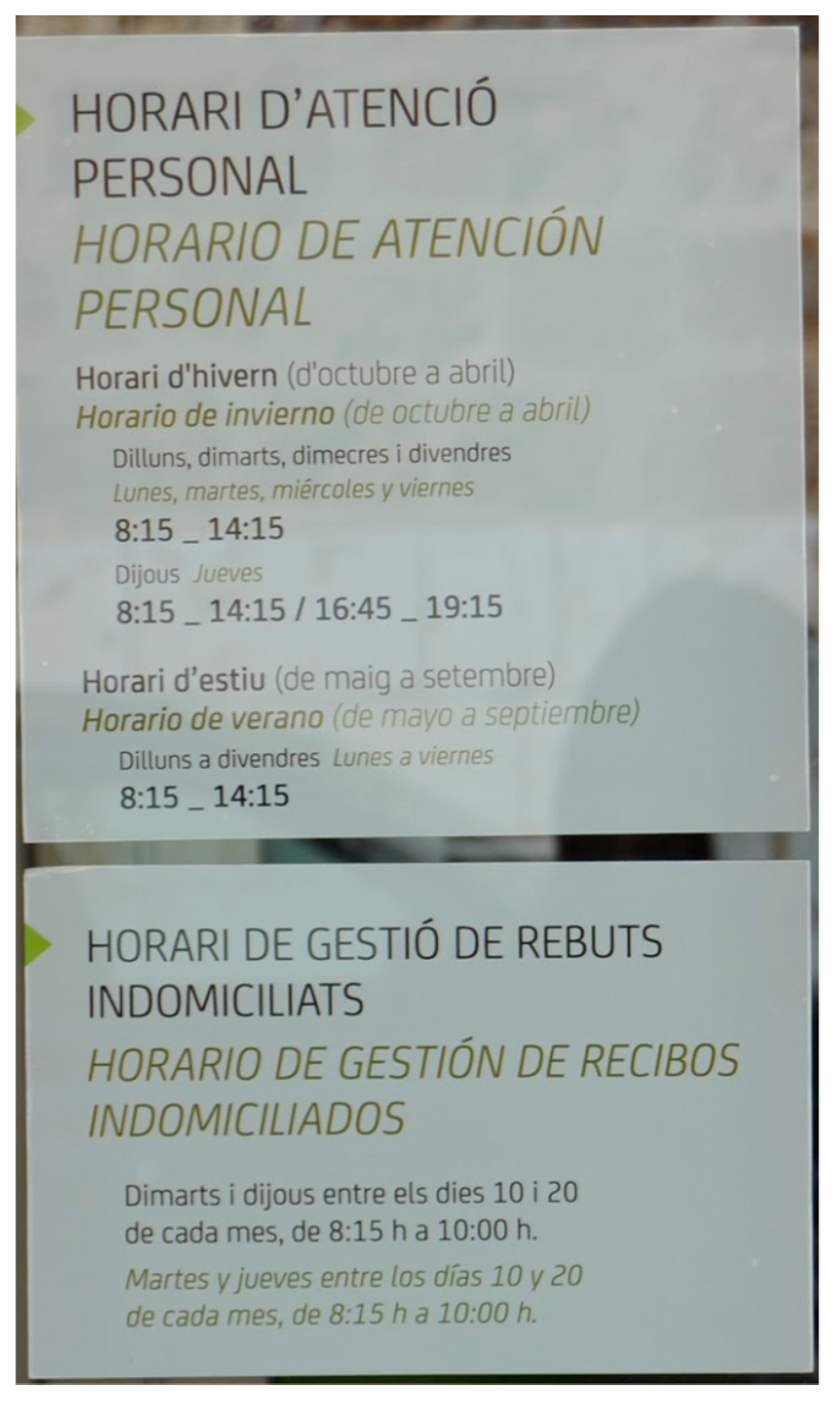

The recurrent pattern in bilingual signs (42%) has to do with the two co-official languages of the region. Some shop names are in Valencian, but Spanish is the selected language to communicate additional information. Evidence can be found in health food (

Figure 30) and stationery shops (

Figure 31).

Notwithstanding, bilingual signs in English-Valencian (4%), English-Spanish (15%), and Romanian-Spanish (4%) can be observed. English is the dominant language in the items below as English is the language of instruction in these language academies. In

Figure 32, Valencian patterns seem to be smaller, whereas in

Figure 33 Spanish is highlighted with a different colour and font size.

Figure 34 is a Romanian-Spanish sign. The flag and the shop name are Romanian rather than Spanish, which is used to attract the Romanian community living in Almazora as well as local customers. Other international languages such as Italian appear as the only language on certain signs (

Figure 35).

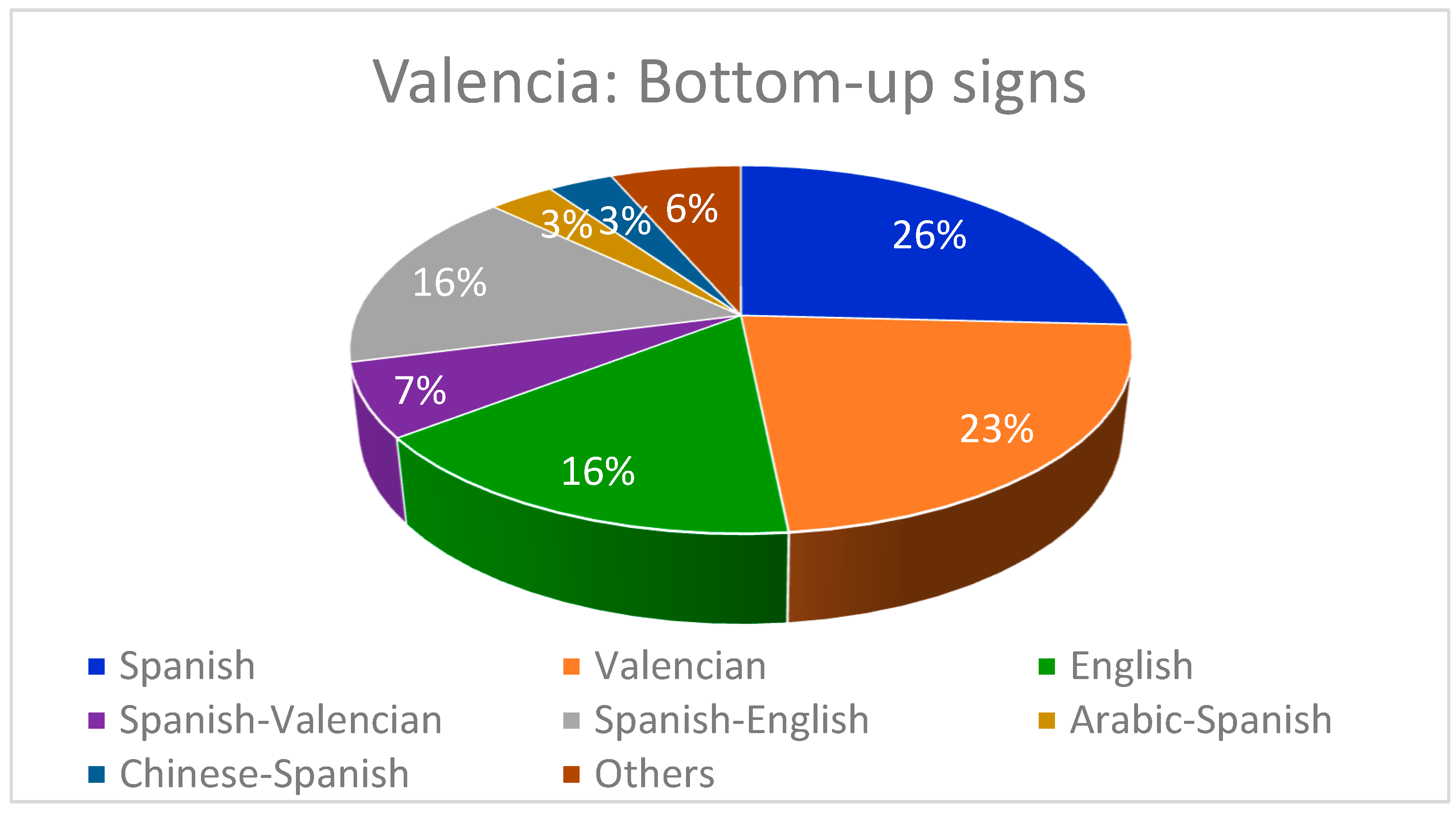

When it comes to Valencia, 65% of nonofficial signs are monolingual. The linguistic landscape of the city seems to be dominated by Spanish (26%), closely followed by Valencian (23%) and English (16%) (

Figure 36).

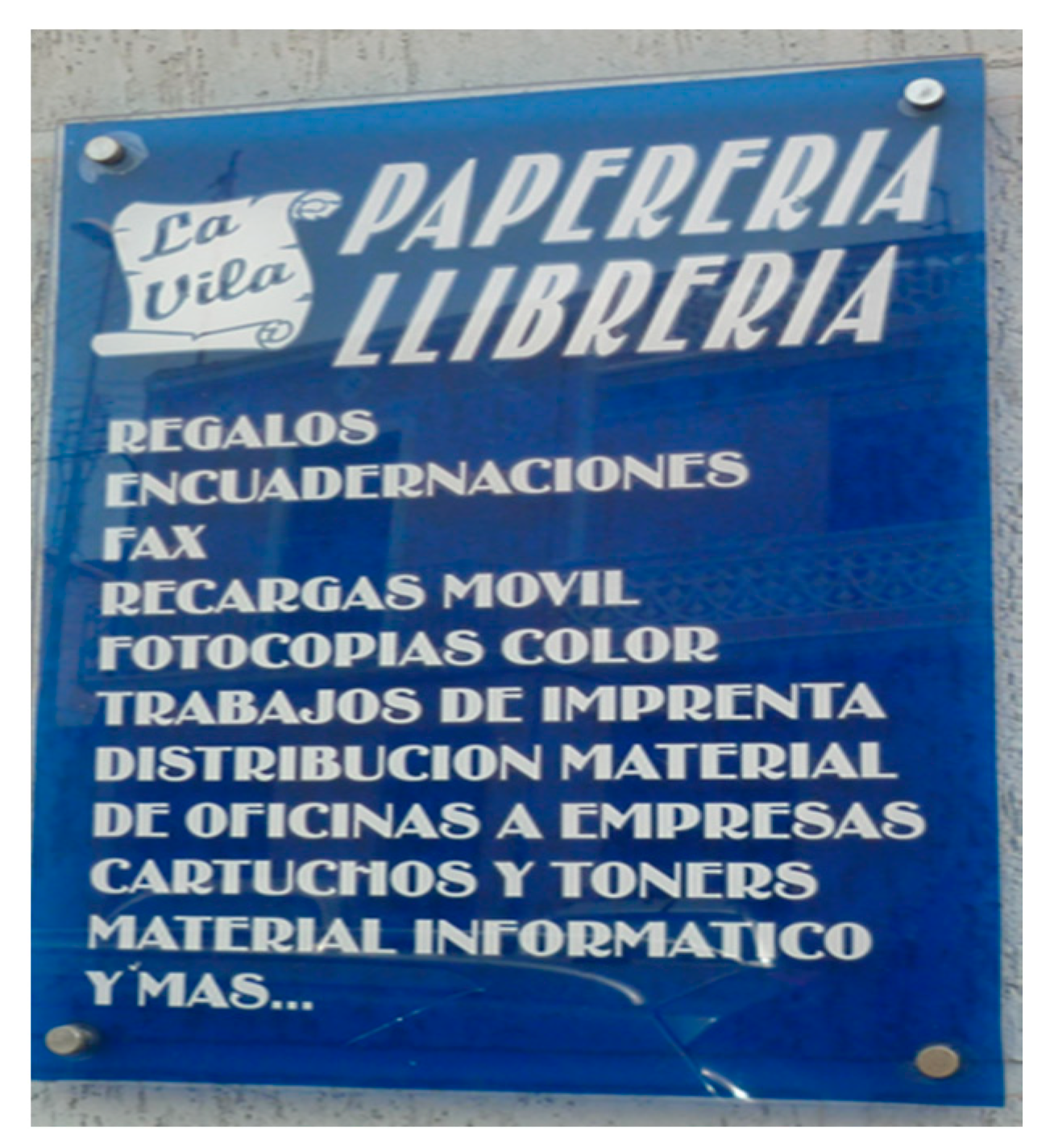

The bilingual landscape (29%) in Valencia is determined by private initiatives, since they are concerned with strategic marketing decisions dealing with companies’ international orientation. Taking this into account, the most predominant languages in bottom-up signs include Spanish, Valencian, and English.

Figure 37 is a Spanish-English sign. As can be observed, the properties of the font-size employed in this bilingual item reveal that Spanish is the dominant language. Actually, the name of the bookshop, which is in English, is smaller.

Efforts to promote the minority language have also been made by regional supermarkets, where products are signed in both co-official languages. No differences in terms of font properties are recognised, so it can be stated that Spanish and Valencian have the same status (

Figure 38).

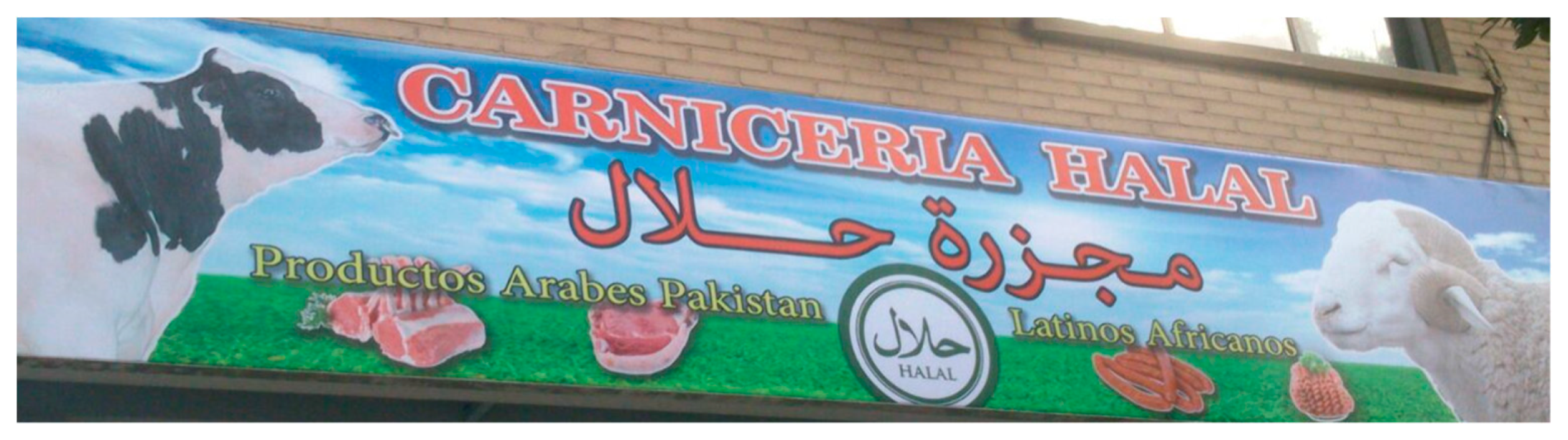

Other languages used in nonofficial signs are Arabic, Italian, and Chinese. A clear example is that of the Arabic butchery (

Figure 39). The presence of both Arabic and Spanish indicates that the patrons of this business are local and Arabic communities. Nonetheless, the use of Arabic is limited to translate the Spanish name, with the latter also being used to describe the kind of products they offer.