Abstract

Computer-mediated communication (CMC) and e-communication tools have introduced new pedagogical tools and activities that contribute to the development of language learners’ academic, multilingual, and intercultural skills and competences. Moreover, CMC has reinforced communication and collaboration between individuals and educational institutions through projects of intercultural language exchanges (ILE). Most of these exchanges idealise ‘nativeness’, and assert the L1 speaker as an expert ‘by default’. These models of ILE believe that the incorporation of a L1S is key to the creation of learning opportunities. This paper contests this belief. The one-to-one online video conversations took place on Skype between language learners of English and/or French over a period of four months. The dyads comprise the following speakers’ constellations: a L1S of French with a L1S of English, and a L1S of English with an Algerian (L2/LF of French and English). To assure equity in the use of languages, I scheduled two sessions every week, one in English and the second in French. This paper investigates the expert/novice dichotomy and how it is negotiated in the learning opportunities they have created. It also casts light on the speakers’ communicative strategies and linguaculture(s) included in overcoming intercultural misunderstanding and miscommunication when using or not using their L1, French and/or English. These intercultural interactions have uncovered that the novice–expert roles alternate between the speakers despite the language of communication and their L1s. The interactants used several strategies and channels, namely pragmatic strategies such as repetition, nonverbal cues to ask for clarification and signal intercultural misunderstandings, translanguaging and their multilingual repertoires in order to construct meaning, achieve their communicative goals or in case of the lack of linguistic resources.

1. Introduction

In this ever-globalised world, foreign language learning is no longer confined to educational institutions since electronic communication has been facilitated through the technologies that offer easy access to other language speakers and cultures (Kramsch and Thorne 2002). In the field of English language learning (ELL) and teaching (ELT), there has been a considerable emphasis on the inclusion of cultural content about the self and the other in education (Risager 2007). Internet, which has become in the last few decades a virtual space for socialisation, learning, teaching, entertaining, etc., has been considered as a fertile area for researchers to investigate online behaviour(s), and/or to compare between the human behavior in real life and virtual spaces. The second main reason is thus studying internet users’ or participants’ online behaviours (Walther 1999). Given the global mobility that has been promoted by online means of communication, the behaviours that are under the loop in this study are the communicative ones. In this respect, (Seidlhofer 2011) underscores that e-communication tools “have accelerated and forced changes in the nature of communication: the media now available have changed the modes of use”. We have to acknowledge that these tools have ‘freed’ communication from spatial and temporal frames, and also emphasised the use of language as vehicular of meaning to achieve interlocutors’ communicative goals.

This virtuality in communication does not hinder face-to-face interactions because it allows electronically simulated face-to-face conversations. In other words, communication technologies mediate video interactions. Skype, for instance, is one of the many platforms that allow electronic face-to-face interaction. Kappas and Krämer point out “[b]y means of [Skype] and a small webcam, as integrated in conventional PCs or laptops, one can conduct video-mediated conversations with people all over the world who use the same technology” (Kappas and Krämer 2011, p. 3). Furthermore, computer-mediated communication (CMC) does not only offer a platform for communication but also contributes to it. The ability to arrange online face-to-face conversations allows the nonverbal language to contribute to communication as it normally does in face-to-face communication. Moreover, the intercultural dimension is much emphasized because the CMC affordances contest the traditional known challenges, namely geographical locations and time zones. In other words, the cultural aspect could have its place through the inclusion of speakers from different linguacultural backgrounds.

Many research findings have proven the efficiency of online international partnerships in engaging students in collaborative projects and intercultural communication through the use of English and a few other languages (Guth et al. 2012; Kern 2015). Those partnerships target mainly L1 speakers and ignore the inclusion of other populations who could participate with their foreign languages. That is, the expert role is already assigned to the partners before even undertaking the exchange. As a result, this undervalues the abilities and competences of other partners and promotes the existing unbalances, especially those related to imperialistic powers.

Furthermore, research that has been undertaken on CMC focalizes mostly on the affordances of the online platforms while little has looked at the dynamics of learning and communication through those platforms (Liddicoat and Tudini 2013). For this, this paper aims at bringing into light how the affordances of CMC intertwine with the communicative dynamism to shape online communication. To achieve this, L1 and non-L1 speakers of English and French are paired and engaged in online video conversations. The asymmetries related to languages status, proficiency and/or deficiency will be scrutinized in the light of the sociocultural theory. The motives behind undertaking such a study are mainly to highlight the potential opportunities available for online exchanges outside the boundaries of L1 speakers in order to be more inclusive of foreign language(s) learners all over the world.

2. Study Design and Corpus

This study took place in an online setting where language learners, who have different linguacultural backgrounds, are involved in synchronous conversations. These intercultural conversations were held on Skype to allow more than two interactants, myself (the researcher) and two speakers, to be involved in synchronous audiovisual conversations. Ideally, the conversations took place twice a week, one in English and the second in French. There were eight culture-related topics:

- How people introduce themselves

- Family gatherings

- Neighbours

- Punctuality

- Foreigners

- Women

- Elderly

- Celebrations

At first glance, such a design can take our attention to the use of a task-based approach in language teaching and learning. It should be recognized that there exist synergies between computer/technology-assisted language learning and a task-based approach (Thomas and Reinders 2010). In order to have a better understanding about the nature of this study, it is of great importance to bring into light the definition of ‘task’. According to Ellis (2003),

A task is a workplan that requires learners to process language pragmatically in order to achieve an outcome that can be evaluated in terms of whether the correct or appropriate propositional content has been conveyed. To this end, it requires them to give primary attention to meaning and to make use of their own linguistic resources, although the design of the task may predispose them to choose particular forms. A task is intended to result in language use that bears a resemblance, direct or indirect, to the way language is used in the real world. Like other language activities, a task can engage productive or receptive, and oral or written skills, and also various cognitive processes.(p. 16)

Undoubtedly, there are few overlaps between this study’s design and Ellis’ definition of task in the sense that these language(s) learners/users get involved in this study through the use of their linguistic resources and repertoires as well as inherited and co-constructed meanings. However, evaluation is neither planned nor intended. That is, the aim of this study is to tease out the (intercultural) communicative tendencies and strategies of language(s) learner/users, especially in instances of (intercultural) non- or misunderstandings. Moreover, it should be noted that all the guidelines provided prior to the conversation do contain a clear statement whereby the interactions are meant to be as natural as possible and any deviation from the pre-set topics would be accepted. The pre-set topics along with their guidelines work as stimuli and (ready-made) initiations for the interaction, and for the speakers to return to in case they run out of ideas and topics for discussion. To make it short, I can argue that this study has been inspired by a task-based approach but it does not conform to it.

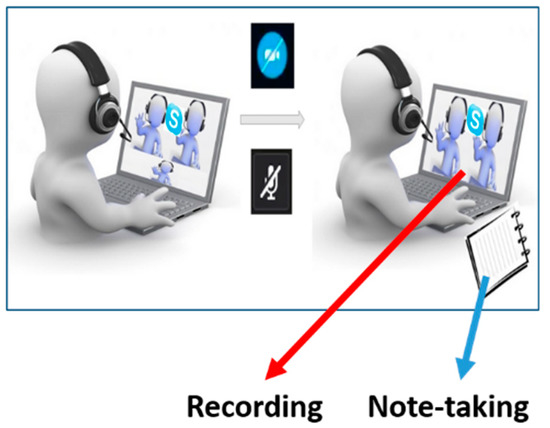

During the interactions, the researcher’s role is to start the call, give the guidelines about the topic of the conversation, and then close the conversation. The role I play then is to record, observe and take notes. When the two speakers express their readiness to start the conversation, the researcher turns off the mic and cam to avoid any interruption or interference (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data collection process (video-recording the conversations).

The pairs involved in the study are presented in Table 1. The latter informs about the linguistic and cultural backgrounds of both speakers in each pair.

Table 1.

Participants’ linguacultural backgrounds.

After the transcription process, the conversations content was coded using NVivo. The excerpts below are taken from the code “learning opportunities”. The extracts below are taken from English and French interactions of the pairs shown in Table 1. In order to make them eligible for the reader, the French extracts contain interlanguage translation with the glosses that correspond to the scope of this paper. The incorporation of any language(s) other than the language of interaction is italicised, so that it can be distinguished.

3. Hesitating Novice and Provoked Expert

In this corpus, hesitation represents one communicative strategy through which the interactant expresses their incertitude about the correctness and/or appropriateness of linguistic items and forms, and also about their intelligibility. In most cases, the former use triggers a learning opportunity, which is the main focus of this paper. That is, the incertitude expressed by the speaker is often understood by the listener as a call for correction or confirmation. The interaction cannot move forward, at least in the same point, until this incertitude is faded away. Admittedly, because hesitation signals the speaker’s “inability to move into action after making a decision (MacIntyre and Doucette 2010, p. 164), the contribution of the listener here is of great importance in making the speaker relaxed and reassured, and also in protecting the communication from any potential breakdown.

EXTRACT 1

| 1. Sonia: | yeah sure <EYEBROWS UP> erm my brothers never ask my mother or never tell us where they go and how they spend the day and with whom erm the parents or the mother generally is very au-tho-ri-ta-ry <SPELLING IT SLOWLY IN ENGLISH> like autoritaire <PRONUNCED IN FRENCH> authoritary <NOSE UP> |

| 2. Gracie: | erm <HALF OF UPPER LIP UP> <LOOKING LEFT> authoritative |

| 3. Sonia: | Authoritative <ASCENDING INTONATION> |

| 4. Gracie: | yeah <SMILE> |

| 5. Sonia: | on her daughter than her son |

To give it a context, this extract is taken from an interactional event in an English conversation where Sonia and Gracie are discussing how social conventions dictate to females certain behaviours, and how parents in turn impose them in case daughters intentionally or unintentionally want to violate them. In turn 1, Sonia shows hesitation by articulating the word “authoritary” slowly, i.e., she almost gave a syllabification to the word. She appears not to be convinced about the correctness of the word when she browses her French repertoire to come up with autoritaire. The use of autoritaire here may have several indications. First, she is initiating a self-repair by using a shared repertoire between her and Gracie. By this, there is an uncertainty in that the word “authoritary” could have conveyed the target meaning. Second, “like autoritaire” may stand as a signal of linguistic weakness and a call for assistance or correction. According to both interpretations, because it is followed by “authoritative”, a nonverbal cue that indicates uncertainty, autoritaire has not functioned as a replacement of an equivalent English word but rather as a way to reach out the latter.

Sonia deploys hesitation followed by code-switching then hesitation. Those strategies signal the need of an expert to rescue a novice. That is, she categorises herself as a novice and provokes the role of expert to Gracie. In turn 2, after showing a slight hesitation, Gracie accepts to be an expert by correcting the token. After that, the novice role has not been abandoned. In other words, Sonia’s next turn shows a need for another assistance. Repeating “authoritative” with a tone of uncertainty does indicate that she is taking a novice orientation, and emphasising the novice–expert dichotomy between her and Gracie. Likewise, Gracie does not resist or hesitate in answering Sonia’s need that is correction. As a result, the interaction in this extract conforms to the self-initiated other-repair, as Schegloff et al. (1977) put it, which then ends by turn 5 when Sonia returns to completing her idea in turn 1.

Hesitations and code-switching are deployed to reflect an uncertainty attitude vis-à-vis the correctness of the linguistic token “authoritary”. The uncertainty attitude creates an asymmetry regarding Sonia’s use of English in this interaction, which makes her not only proclaiming a novice role but also the one managing the novice–expert orientations by taking one role and provoking another. In other words, the asymmetry is not intended nor negotiated with Gracie, yet triggered by a deficiency in Sonia’s repertoire of English. The situation provokes Gracie to respond to Sonia’s attitude by taking over the role of an expert. The process of being a hesitating novice and provoked expert produces a self-initiated other-repair that hinders any disruptions to achieving the speakers’ communicative ends.

EXTRACT 2

| 1. Louisa: | elle parle <LOOKING DOWN> français <COUNTING IN FINGERS> allemagne et je pense qu’elle parle <EYES BARELY OPEN> <LOOKING LEFT> <EYEBROWS LOWERED> une langue scandinavi <HESITATING> scandinavi <ASCENDING INTONATION> <EYE CONTACT> |

| (She speaks <LOOKING DOWN> French <COUNTING IN FINGERS> Germany and I think that she speaks <EYES BARELY OPEN> <LOOKING LEFT> <EYEBROWS LOWERED> a scandinavi language <HESITATING> scandinavi <ASCENDING INTONATION> <EYE CONTACT>) | |

| 2. Shayma: | scandinave <SMILE> |

| (Scandinavian <SMILE>) | |

| 3. Louisa: | oui je sais pas si c’est-peut-être <LOOKING LEFT> Norway <HESITATING> <MOVING RIGHT HAND FIRST FINGER UP AND DOWN> Norwegian <ASCENDING INTONATION> <NOSE UP> <EYE CONTACT> |

| (Yes I don’t know whether it is-maybe <LOOKING LEFT> Norway <HESITATING> <MOVING RIGHT HAND FIRST FINGER UP AND DOWN> Norwegian <ASCENDING INTONATION> <NOSE UP> <EYE CONTACT>) | |

| 4. Shayma: | ah oui norvégien <LOOKING UP> |

| (ah yes Norwegian <LOOKING UP>) | |

| 5. Louisa: | oui parce que je pense que <EYEBROWS LOWERED> que son père erm <LOOKING UP LEFT> il était erm <PRESSING EYES> [Norwegian] |

| (yes because I think that <EYEBROWS LOWERED> that her father erm <LOOKING UP LEFT> he was erm <PRESSING EYES> [Norwegian]) | |

| 6. Shayma: | [de] oui d’accord ahum |

| ([from] yes okey ahum) |

This excerpt, which is taken from a French conversation, also shows how the novice role is taken while the expert is provoked. Louisa deploys some nonverbal cues (see turn 1 the cues between <>) and the token “scandinavi” to indicate the inability to find the right suffix or to form the word scandinave. To add, “scandinavi” could mirror how Louisa’s English and French repertoires intermingle and cause such a confusion. The eye contact by which she ends her turn also serves as a signal to give away the floor to Shayma to complete the word or provide a correction. In this respect, eye contact represents a sharp edge as it distinguishes between the speaker and listener roles. Indeed, Shayma takes a double role, speaker and expert. Each of the roles are fulfilled once a response to Louisa’s need has been delivered. It is scandinave that indicates that Shayma has accepted being a speaker with expert orientation.

Turns 3 and 4 illustrate the same asymmetry expressed in the previous turns. However, Louisa in turn 3 utilises communicative tokens different from the ones used in turn 1. The inclusion of the English repertoire is much explicit. The use of code-switching by the inclusion of “Norway” and “Norwegian” reflects how the repertoire of English and French interconnect and interact. The way in which those items are uttered hold hesitation, a call for assistance, or more precisely for translation, and/or a confirmation for intelligibility. Shayma ignores the first call and only responds to the second. That is, she does only give the equivalent for the lastly uttered word, “Norwegian”. Nonetheless, this does not deprive her from the expert role. Similarly to turn 3, turn 5 starts by oui, a confirmation from Louisa that Shayma’s response is the one needed.

The sequence above is made up of two self-initiated other-repairs. In the two cases where Louisa signals a problem through first hesitation, then hesitation and code-switching, there is a repair offered, and hence the problem resolved. Although the dynamics of this repair differ from that in extract 1, the deployed strategies and how the expert–novice dichotomy has been invoked remain alike. In sum, extracts 1 and 2 show how the novice is an unescapable situational role while the expert is an interactionally-responsive and provoked role.

4. Implied Expert–Novice Orientations

The asymmetry may sometimes be indirect without any mechanisms, strategies, or machinery. In this situation, the expert–novice orientations emerge implicitly without being preceded or followed by any signals. In some cases, like the one illustrated below, not all speakers should cooperate or be incorporated, though they are implicitly involved.

EXTRACT 3

| 1. Louisa: | <LAUGHTER> oui oui et tu as beaucoup de faire avant d’aller en Italie erm |

| (<LAUGHTER> yes yes you have a lot to do before you go to Italy erm) | |

| 2. Shayma: | oui |

| (yeah) | |

| 3. Louisa: | tu as beaucoup de faire oui |

| (you have a lot to do yeah) | |

| 4. Shayma: | oui parce que je reste une semaine puis je pars en séjour et j’ai plein de trucs à faire |

| (yes because I stay one week then I go on holiday and I have many things to do) | |

| 5. Louisa: | tu as des choses à faire avec tes amis |

| (you have things to do with your friends) | |

| 6. Shayma | ah oui j’aimerais bien les voir […] |

| (ah yes I would really love to see them […]) |

Even though there is no potential nonunderstanding, misunderstanding, unintelligibility or any other risk for communication breakdown, novice–expert orientations still take place in extract 3, an interactional event in a French conversation. In Louisa’s two first turns, there is a repetition of the sentence tu as beaucoup de faire (“you have a lot to do”). The repetition might be used to encourage Shayma to give further information about her readiness for her trip to Italy, or to seek feedback on the correctness of this phrase. Shayma’s utterance, turn 4, takes a clarifying account without referring to nor correcting Louisa’s sentence. Instead, she inserts j’ai plein de trucs à faire to emphasise how she is pressed for time.

On the other hand and according to Louisa’s turn 5, the novice and expert roles are still allocated to Louisa–Shayma respectively. If we are to compare the syntactic structures of Louisa’s sentence in turns 1 and 3 with the one in turn 5, the differences would be dismissing the phrase (Adj+Preposition) beaucoup de, introducing the plural noun choses preceded by a plural indefinite article des, and adding the preposition à.

Louisa’s adaptation of Shayma’s sentence j’ai plein de trucs à faire to tu as des choses à faire idealises Shayma’s use of French. That is, the identity of Shayma as a L1 speaker is highlighted by being a model whose use of the language, French in this case, should be imitated.

The change conducted on Louisa’s sentence (Table 2) assigns to her a novice orientation while conceiving Shayma as a model attributes to the latter an expert orientation. It appears that Louisa chooses such an implicit division of roles based on the fact that Shayma is a L1 speaker of French. Perceiving L1 speakers as a model implies giving them the status of an expert and considering non-L1s as novices. This operation, including the change or adaptation of form, does not have an apparent linguistic or didactic orientation. None of the turns in extract 3 hold signals to any linguistic weakness or to seeking assistance and correction. Moreover, even after Louisa’s adjustment, no one has given comment on the linguistic form. Instead, the conversation goes on (see turn 6) focusing on the messages’ content rather than form, i.e., grammatical accuracy and correctness.

Table 2.

Form/syntactic adaptation.

In extracts 1 and 2, the L1Ss accept to take up the role of expert. As mentioned above, their responses to the hesitating novice show their acceptance to be identified as experts. On the other hand, as shown in extract 3, the expert role can be implied instead of being triggered. Besides, the novice is implicitly embraced. With no strategy indicating the need for linguistic assistance or correction, the novice, Louisa, here deploys an aspirational learner role. Despite that the interaction is not explicitly shaped to take the form of a learning environment, she ends up adjusting her utterance through imitating Shayma’s use without interrupting the interaction flow or giving it a mere didactic orientation.

5. Assigned Expert–Novice Roles

L1 speakers may cherish idealisation, which can be unveiled through explicit and direct communicative practices and strategies. In most of the cases, this idealisation is performed when a non-L1 interacts as a novice learner. In this context, this novice generally gives up the language user role and identifies as a language learner. Ideally, the learner addresses the L1 speaker as a language teacher instead of a language user.

EXTRACT 4

| 1. Tania: | right yeah so how’re your family gatherings |

| 2. Elise: | how do you spell gatherings I don’t know |

| 3. Tania: | erm yeah erm [<TYPING ON SKYPE>] |

| 4. Elise: | [it’s like gatherings the order or] |

| 5. Tania: | it’s like |

| 6. | <TEXT MESSAGE SENT BY TANIA RECEIVED BY ELISE> |

| 7. Elise: | <GETTING CLOSER TO SCREEN & LOOKING DOWN TO READ THE MESSAGE> oh I’ve never heard of this word before <LAUGHTER> |

| 8. Tania: | it’s like special occasions like Christmas or birthdays or <DESCENDING INTONATION> |

| 9. Elise: | ok <LAUGHTER> I’ve never heard of this word before so |

| 10. Tania: | yeah <HEAD NOD> <SMILE> |

| 11. Elise: | in my family each Sunday <SHORT PAUSE> |

Extract 4 is taken from an English conversation. In turn 2, Elise identifies herself as a novice through a direct question querying the spelling of the linguistic token “gatherings” and a statement to highlight a lack of knowledge “I don’t know”. Tania hesitates on how to answer Elise then decides to send her the word in a text message on Skype. After receiving it, Elise asserts that the word has not been introduced to her English repertoire. This has led Tania to give examples where gatherings usually take place. In spite of this, Elise re-asserts that the word is new. This process is very straightforward and smooth. On one hand, Elise does not show any hesitation to express her novice-ness. Tania, on the other hand, takes up the expert role assigned to her.

EXTRACT 5

| 1. Tania: | mais la ville e::h était très belle et erm très veille /vɛj/ |

| (But the city e::h was very beautiful and erm very eve) | |

| 2. Elise: | <EYES BARELY OPEN> veille <ASCENDING INTONATION> vert /vɛʀ/ |

| <EYES BARELY OPEN> eve <DESCENDING INTONATION> green | |

| 3. Tania: | une veille or like vieux /vjø/ |

| (an eve or like old-MAS) | |

| 4. Elise: | eh ok vieux |

| (eh ok old) | |

| 5. Tania: | vieux on dirait la ville était |

| (old we would say the city was) | |

| 6. Elise: | la ville est vieille /vjɛj/ |

| (the city is old-FEM) | |

| 7. Tania | vieille oui la ville était vielle n’est pas moderne […] |

| (old-FEM yes the city was old-FEM was not modern […]) |

In extract 5, emerged in a French interaction, the mispronunciation of the word vielle/vjɛj/ in turn 1 causes a nonunderstanding signaled in turn 2, which alters the interaction nature being narrative (Tania talking about her trip to a Belgian city) into a didactic nature focusing on the meaning, correctness, and appropriateness of the use of veille, which literally means eve. The adjustments that Tania made are vieux, a masculine adjective, and “old”, the equivalent in English. These linguistic tokens are retrieved from the French and English repertoires respectively, and share the same meaning. As a result, this forms a four-turn other-initiated self-repair, that is signaled by Elise and repaired by Tania.

As the interaction goes on, Tania does not seem to get the assistance she aimed for when she provided the masculine form of the adjective. The incompatibility between the gender of vieux and ville leads to violating adjective–noun agreement, which she clearly wants to avoid in turn 5. Tania’s strategy to do so consists of incorporating Elise in a sentence completion task. The only item that the sentence lacks is the adjective veille. Although turns 1 to 4 clearly show that Tania is taking the role of a novice who is looking for the correct feminine from of the adjective vieux, the task given to Elise may indicate that the roles are reversed. To explain, the task takes a form of scaffolding through which teachers mediate their students to encourage them to find the right answer(s).

Consequently, Tania is adopting an expert practice in order to stimulate the ‘real’ expert to finalise the other-initiated (turn 2) other-repair (turn 6). In the end, one can argue that Tania’s strategies are deemed to be successful, especially since she adequately triggered two repairs. The first repair (turns 1 to 4) that is other-initiated self-repair contributes to the construction of the other-initiated other-repair. In addition, the process of claiming a novice identity and uptaking the expert runs smoothly from one turn to another without causing miscommunication.

What is common between extract 4 and 5 is that the asymmetry has been distributed in a systematic way. That is, the non-L1 speaker of either of the languages, French and English, assigns to herself a novice identity by which she shows lack of linguistic knowledge. By this, the L1 performs a complementary role, yet may be also seen superior to that of a novice. Being the more knowledgeable, language-wise, assigns to her the expert role. Those roles imply unequal transformation of the roles of languages’ users; one becomes the ‘imperfect’ whereas the other becomes the model.

6. The Outsider Expert

The imperfect-model may be contested when speakers perceive themselves as equal contributors to the interaction and users of language(s). Any difficulty, weakness, confusion, or uncertainty can be addressed to someone and/or ‘something’ not involved in the interaction, an outsider, instead of the expert ‘by default’.

EXTRACT 6

| 1. Elise: | and lot of cities organise a parade <PRONOUNCED IN FRENCH> <WHISPERING> <HESITATION> |

| 2. Tania: | here in Southampton or in Birmingham |

| 3. Elise: | I’m just looking for the word in English <SEARCHING ON WEB> because I don’t know the word <LAUGHTER> |

| 4. Tania: | a parade |

| 5. Elise: | yup a parade |

In turn 1, Elise makes use of her French repertoire to find the word “parade”. Although uttered in French, it did not cause any confusion for Tania as turn 2 shows. Despite that, Elise prefers to look up the equivalent in English. This does not allow the conversation to carry on in its intended direction because being immersed in the online dictionary results in not being able to give an answer to Tania’s query. Turn 3 pushes Tania to use her ‘default’ identity, and thus provide the searched token. Afterwards, Elise confirms Tania’s answer as it apparently matches the one given by the dictionary.

According to Elise’s practice of forwarding her query to the online dictionary, the latter here is undoubtedly the expert while both speakers, Tania and Elise, are novices. However, Tania challenges and also negotiates this distribution of role by spontaneously performing her ‘default’ identity of expert. To add, another negotiation takes place in turn 5. The act of confirming the answer of Tania does categorise Tania as a novice, or an expert with an inferior position in the presence of the online dictionary. The whole interaction illustrated in extract 6 portrays how the affordances of communication technologies may lead to rejecting the ideology of idealising L1 speakers. That is, and in this particular situation, the online dictionary plays the role of a mediator that facilitates the novice’s learning of a ‘new’ linguistic token.

EXTRACT 7

| 1. Elise: | non t’as raison <LOOKING DOWN ON HER PHONE> en traduisant sur mon dictionnaire le mot gêne veut dire I try <LAUGHTER> awkwardness |

| No you’re right <LOOKING DOWN ON HER PHONE> when translating in my dictionary the word awkwardness means I try <LAUGHTER> awkwardness | |

| 2. | <SHORT PAUSE> |

| 3. Elise: | [awkWardness a w k w a r d <SPELLING>] |

| 4. Tania: | [<GETTING CLOSER TO SCREEN>] awkwardness |

| 5. Elise: | yes |

In extract 7, Elise is trying to accommodate Tania’s communicative needs by explaining the French word gêne through English, Tania’s L1. Given that this interaction is in French and her linguacultural background (Table 1), Elise is being the expert here; the one who knows the meaning of gene. However, “I try” in turn 1 does show that the dictionary has a superior expert position. Moreover, switching to English and not being able to pronounce “awkwardness” have promoted Tania’s position from novice to an in-between position, i.e., neither a mere novice nor a mere expert. In a way, her position alternates as the language changes. Nevertheless, the alternation does deprive the dictionary from being an ‘outside’ expert.

EXTRACT 8

| 1. Gracie: | comment est-ce qu’on dira ça like a chain chain |

| (how to say this like a chain chain) | |

| 2. Sonia: | une série |

| (a series) | |

| 3. Gracie: | comment <GETTING CLOSER TO SCREEN> |

| (how <GETTING CLOSER TO SCREEN>) | |

| 4. Sonia: | une série |

| (a series) | |

| 5. Gracie: | <EYEBROWS LOWERED> mais est-ce qu’on peut dire <RIGHT EYE BARELY OPEN> ça pour les shop-magasins qui sont <MOVING PALMS IN PARALLEL POSITION ALTERNATIVELY> |

| (<EYEBROWS LOWERED> but can we say <RIGHT EYE BARELY OPEN> this to the shop-shops that are <MOVING PALMS IN PARALLEL POSITION ALTERNATIVELY>) | |

| 6. Sonia: | oui <HEAD NOD> <EYEBROWS UP> |

| (yes <HEAD NOD> <EYEBROWS UP>) | |

| 7. Gracie: | aussi les séries <EYEBROWS UP> <EYES WIDELY OPEN> |

| (also the series <EYEBROWS UP> <EYES WIDELY OPEN>) | |

| 8. Sonia: | oui |

| (yes) | |

| 9. Gracie: | ah ok je savais pas erm <LOOKING RIGHT> |

| (ah ok I did know erm <LOOKING RIGHT>) | |

| … | |

| 10. Sonia: | erm à propos de chain on peut dire aussi chaine de magasins |

| (erm concerning chain we can also say chain of shops) | |

| 11. Gracie: | chaine merci <SMILE> |

| (chain thank you <SMILE>) | |

| 12. Sonia: | de rien |

| (not at all) |

The first four turns are similar to extracts 4 and 5. In this event extracted from a French interaction, Gracie plays the role of novice and Sonia the role of Expert. The following turns, especially turns 5 and 7, create a sense of doubt vis-à-vis the appropriateness of the use of séries for shops. This doubt affects Sonia’s confidence, and also signals the need to negotiate or repair the meaning of chain. Sonia’s response in turn 6 is firmer than that in turn 8. That is, in turn 6, she accompanies her verbal affirmation with the nonverbal cues, namely nodding her head and raising up her eyebrows. In turn 8, however, this affirmation was not endorsed by any nonverbal signal. After a few turns, Sonia goes back to translating the word chain through an online dictionary. At last, she makes up her answer and adopts the one provided in the dictionary. In such a case, she gives up her assigned expert role to the dictionary. This process of repair ends by Gracie appraising Sonia’s effort to finding the French equivalent to chain. By going through the process of trigger, signal, response, then reaction, this interactional event mirrors a meaning negotiation instance (Doughty 2000; Nakahama et al. 2001).

EXTRACT 9

| 1. Sonia: | […] c’était un mais je sais pas si c’est un offre ou une offre <LOOKING UP> |

| ([…] it was a-MAS but I do not know whether it is an-MAS offer or an-FEM offer <LOOKING UP>) | |

| 2. Gracie: | <LAUGHTER> |

| 3. Sonia: | c’est toujours un problème entre un et une <LOOKING AROUND> <EYEBROWS LOWERED> |

| (it has always been a problem between an-MAS and an-FEM <LOOKING AROUND> <EYEBROWS LOWERED>) | |

| 4. Gracie: | ça me fait sentir très <RIGHT HAND ON CHEST> je suis très contente quand tu fais des erreurs comme moi |

| (this makes me feel very <RIGHT HAND ON CHEST> I’m very happy when you make errors like me) | |

| 5. Sonia: | oui c’est toujours un problème |

| (yes it’s always a problem) | |

| 6. Gracie: | oui c’est difficile <LAUGHTER> |

| (yes it’s difficult) | |

| 7. Sonia: | <SEARCHING ON WEB> ah c’est une <SHORT PAUSE> |

| (<SEARCHING ON WEB> ah it is an-FEM <SHORT PAUSE>) | |

| 8. Gracie: | je croix Ann nous écrit si c’est un ou une <LAUGHTER> |

| I think Ann writes to us whether it is an-MAS or an-FEM <LAUGHTER>) | |

| 9. Sonia: | <LAUGHTER> apparemment c’est un offre-une offre |

| (<LAUGHTER> apparently it is an-MAS offer-an-FEM offer) | |

| 10. Gracie: | c’est un ou |

| (it is an-MAS or) | |

| 11. Sonia: | une offre |

| (an-FEM offer) | |

| 12. Gracie: | une offre très bien donc tu as ton offre |

| (an-FEM offer very good so you have your offer) | |

| 13. Sonia: | oui en fait c’était une offre conditionnelle […] |

| (yes in fact it was a-FEM conditional-FEM offer) |

The gender of the word offre creates confusion for Sonia, the ‘default’ expert in this French interaction. Gracie, who is the novice, expresses her relief in that even the expert could get confused and commit mistakes like her (turn 4). Sonia asserts in turn 3 and 5 that nouns’ genders have always been a problem for her. This declaration then leads Gracie to think of another expert to interfere in the interaction and resolve the problem. She hence suggests Anna, the researcher. At the same time, Sonia chooses the assistance of the online dictionary to finally find out that the word offre is feminine and should be preceded by a feminine indefinite article une.

Gracie’s first reaction to Sonia’s confusion indicates that she perceives her as a model. The idealisation attributed to Sonia has been declined, yet transmitted to the researcher. According to Gracie, the researcher enjoys an expert position higher than that of her peer, Sonia. The latter, on the other hand and as being the expert in this interaction, considers the online dictionary as a legitimate alternative.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

The online video interactions presented above provide many uses of the novice–expert asymmetry within the dyad. The several uses of the novice–expert dichotomy and the shifts in these roles and identities hold a great indication to the non-fixedness of the roles. This in turn contests the fixedness attributed to the presumptions and perceptions in regards to the roles assigned L1-nonL1, also labelled as “NS-NNS”. The fixedness related to those dichotomies lies in considering the non-L1 as an imperfect user, or eternal learner of the language, whereas the L1 as an idealized user. This controversial view claims that the latter always represents a model for the former. That is, the learner or the novice should dedicate every effort in their learning process for the purpose of reaching the L1, i.e., the expert, use of the language. As Hua (2016) put it, the learner is thus regarded as “an unfinished product”.

Admittedly, the interactants have brought into these interactions the expert–novice identities. Bakhtin’s heteroglossia explicates how the language users shift to learner–teacher roles. The non-L1 interlocutors translate the EFL inherited “unfinished product” into assigning themselves novices’ roles. Similarly, L1 speakers are given the idealized status of language users, i.e., the model of the “unfinished product”. However, the aforementioned negotiations and shifts in assigning and accepting these identities go in line with the sociocultural approaches that “deemphasize the stability of systems and the presumptions of consistency across contexts, time periods, individuals, and communities including predefined characteristics such as ‘expert’ and ‘novice’” (Thorne and Hellermann 2015, p. 320). Unlike the findings of Liddicoat and Tudini (2013), it is less common in this study that the L1 speaker claims the ‘default’ expert identity. Rather, it is more common the novice who triggers this identity through seeking assistance. The dyads show great awareness regarding the non-fixedness of those roles. That is, they are negotiated, claimed, accepted, or denied.

Furthermore, this asymmetry, whether assigned, provoked, imposed, negotiated, or denied, does not hinder creating learning opportunities that emerge as ultimate interactional outcomes. In other words, in all the extract discussed above, at least a member of the dyad ends up acquiring a new information, grammatical form and/or a linguistic item. It can then be argued that these online video conversations do contribute to the speakers’ zone of proximate development (Vygotsky 1978). This mechanism acknowledges that the learner needs an expert who teaches or guides them to acquire/learn a certain amount of sociocultural knowledge by which they can partially or totally interact independently, i.e., they develop from learners to experts. In the context of this study, the less knowledgeable, the novice, does rely whether on the peer or the internet affordances to overcome the weakness and acquire new knowledge. To put it differently, this process contributes to the construction of what Bourdieu refers to as linguistic capital (Bourdieu 1992). The participants’ linguacultures or languages proficiency and status do contribute, but not hinder, to the deployment of expert–novice identities in order to achieve the learning opportunity, repair or meaning negotiation. Importantly, the multilingual repertoires of the participants enrich their interactions and encourage understanding and the success in attaining the speakers’ communicative purposes. At last, and given that they are treated as situational and non-fixed, being novice or expert does not create any kind of sensitivity, inferior or superior attitudes.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Algerian government.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Jaine Beswick for her valuable support and guidance and the Languages reviewers and editors for their useful comments. I also would like to express my gratitude to my participants who massively contributed with their passion, devotion and commitment to my research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1992. Language and Symbolic Power. Paris: Arthème Fayard. [Google Scholar]

- Doughty, Catherine. 2000. Negotiating the l2 Linguistics Environment. University of Hawai’i Working Papers in English as a Second Language. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Rod. 2003. Task-Based Language Learning and Teaching. Oxford Applied Linguistics. Oxford: OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Guth, Sarah, Francesca Helm, and Robert O’Dowd. 2012. University Language Classes Collaborating Online. A Report on the Integration of Telecollaborative Networks in European Universities. Available online: https://www.unicollaboration.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/1.2-Telecollaboration_report_Final_Oct2012.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2019).

- Hua, Zhu. 2016. Intercultural communication and elf. In English as a Lingua Franca: Perspectives and Prospects: Contributions in Honour of Barbara Seidlhofer. Edited by Marie L. Pitzl and Ruth Osimk-Teasdale. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kappas, Arvid, and Nicole C. Krämer. 2011. Face-to-Face Communication over the Internet: Emotions in a Web of Culture, Language, and Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, Richard. 2015. Language, Literacy, and Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, Claire, and Steve L. Thorne. 2002. Foreign Language Learning as Global Communicative Practice. Globalization and Language Teaching. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat, Anthony J., and Vincenza Tudini. 2013. Expert-novice orientations: Native-speaker power and the didactics voice in online intercultural interaction. In Language and Intercultural Communication in the New Era. Edited by Farzad Sharifian and Maryam Jamarani. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, Peter D., and Jesslyn Doucette. 2010. Willingness to communicate and action control. System 38: 161–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahama, Yuko, Andrea Tyler, and Leo van Lier. 2001. Negotiation of meaning in conversational and information gap activities: A comparative discourse analysis. TESOL Quarterly 35: 377–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risager, Karen. 2007. Language and Culture Pedagogy: From a National to a Transnational Paradigm. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff, Emanuel A., Gail Jefferson, and Harvey Sacks. 1977. The Preference for Self-Correction in the Organization of Repair in Conversation. Language 53: 361–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidlhofer, Barbara. 2011. Understanding English as a Lingua Franca: A Complete Introduction to the Theoretical Nature and Practical Implications of English Used as a Lingua Franca. Oxford: OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Michael, and Hayo Reinders. 2010. Deconstructing tasks and technology. In Task-Based Language Learning and Teaching with Technology. Edited by Michael Thomas and Hayo Reinders. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, Steve. L., and John Hellermann. 2015. Sociocultural approaches to expert-novice relationships in second language interaction. In The Handbook of Classroom Discourse and Interaction. Edited by Numa Markee. Somerset: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, Lev. 1978. Mind in Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, Joseph B. 1999. Visual cues and computer-mediated communication: Don’t look before you leap. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association, San Francisco, CA, USA, May 27–31. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).