Abstract

Monosyllabic place holders (MPHs) have been studied extensively in first-language (L1) acquisition of Spanish and other Romance languages. However, the study of MPHs in second-language (L2) acquisition, both by children and adults, has received much less attention. This study provides evidence for the presence of MPHs in the L2 Spanish of two L1 Moroccan Arabic children living in Spain. The age difference between the children (10;9 for Rachida and 6;10 for Khalid) allows us to address the issue of whether the younger child would use MPHs, as is the case in L1 acquisition. However, what the data show is that both children used MPHs, although Khalid’s MPH rate was slightly higher than Rachida’s. Therefore, based on these findings we argue that MPHs can constitute a strategy available for all child learners of Spanish.

1. Introduction

The study of monosyllabic place holders (MPHs)1 is one of the main issues in research with respect to first-language (L1) acquisition of Spanish and other Romance languages, and has been studied extensively by linguists and psychologists. This article is focused on the use of MPHs in the L2 acquisition of Spanish by children.

Monosyllabic place holders are linguistic elements, mainly vowel-like, which appear in the utterances of many children. They have been identified as appearing: (1) before nouns in the position of determiners and prepositions; (2) before adjectives and adverbs in the position of auxiliaries, copulas, and negative particles; and (3) before some sentences as interrogatives, in the position of complements. These three examples come from Italian, as a very detailed analysis of the position and meaning of MPHs has been performed for this language.

| 1. | torna | [a] babbo | |

| He comes back | [a] daddy | ||

| ‘Daddy comes back.’ | (Raffaello, 1;9,26;2 taken from Bottari et al. 1993–1994, p. 337) | ||

| 2. | [a] | fredda | |

| [a] it’s | cold | ||

| ‘It’s cold.’ | (Viola, 2;1;17; taken from Bottari et al. 1993/1994, p. 338) | ||

| 3. | [e] (dove) | tà (sta)? | |

| [e] (where) | it-stays | ||

| ‘Where does it stay?’ | (Viola, 2;1,17; taken from Bottari et al. 1993/1994, p. 339) | ||

It has been reported that these elements appear earlier (by some months) in children learning Romance languages as compared to children learning Germanic languages (Lleó 1997, 2001a, 2001b; Lleó and Demuth 1999).

The reference to these linguistic elements can be found in the early research on language acquisition. For example, Karmiloff-Smith (1979) studied the primary acquisition of French and English, assuming a psychological constructivist perspective. She proposed two possible explanations about these elements, which have a semantic and a phrasal function: (1) they allow children to distinguish proper nouns (not preceded by these vowel-like elements) from common ones; and (2) they are metalinguistic or metacommunicative, because they allow children to distinguish between thing-like words (which can be preceded by these elements) and action-like words.

These elements have been also called fillers (Peters 1985), schwa fillers or protomorphemes (Peters and Menn 1993), protoarticles (Lleó 1997), amalgams or phonoprosodic forms (López Ornat 1997), and monosyllabic place holders (Bottari et al. 1993–1994). The latter is the term we prefer. In our opinion, it is the most accurate and extensive term, since not all vowels are schwa but they are all monosyllabic elements, and what they all share is the feature of occupying a specific position in the structure of the sentence.

Bottari et al. (1993–1994) studied the acquisition of Italian as an L1. They gathered several explanations for these schwa-like elements appearing in the acquisition process of Italian for some children. The three hypotheses they analyze are: (1) the phonetic-imitative hypothesis (they stem from imitation); (2) the structural-inference hypothesis (they are morphophonologically underspecified functional heads); and (3) the strong morphophonological hypothesis (they are phonologically altered realizations of specific morphophonological items). The hypothesis they defend is the second: MPHs are morphophonologically underspecified functional heads that represent some basic functions of the related real morphemes, like their positions in the structural representation of the sentence. This is also the hypothesis we support, although we consider that the importance of phonetic imitation in the use of MPHs should not be disregarded (see Section 3.3).

According to Bottari et al. (1993–1994), MPHs constitute evidence of the learning process that concludes in the acquisition of free morphology. These elements are in complementary distribution with free morphemes, since they occupy the place of close-class items such as articles, prepositions, clitics, copulas, modals, negative operators, and interrogative pronouns. MPHs identify a position, that is to say, they have a syntactic function since they do not appear randomly, they do not replace lexical items, and they do not precede free grammatical morphemes. They consist of abstract formal features in which not all the features of adult language appear but they maintain the syntactic feature of being the heads of phrases, even if their morphological realizations are not target-like. MPHs are, for them, proof against the hypothesis of a “prefunctional” grammatical period in child language and they share their vocalic features with specific morphemes. Therefore, they can be considered as true attempts to use morphemes.

1.1. Monosyllabic Place Holders in L1Acquisition of Spanish

1.1.1. Spanish Determiner Phrases

According to the literature surrounding the L1 acquisition of Spanish and the instances that we located in our research (see Section 3.1.2), MPHs are always in the place of determiners (Ds), preceding a noun, as in (1).

There is no complete agreement among researchers about which categories can be found in Spanish determiners. A discussion of which elements can be classified into Ds and the features of each is outside the expected limits of this work. We refer the reader to Eguren (1989, 2006), Demonte (1999), Laca (1999), Leonetti (1999), Real Academia Española (2009) and our previous work (Nicolás 2016). According to Eguren (1989), determiners are formed by articles, demonstratives, possessives,3 cardinal numerals, and some quantifiers and indefinites; the Real Academia Española (2009) includes in D articles, demonstratives, pronominal possessives and nominal quantifiers. Nevertheless, we would like to point out some characteristics of the articles in Spanish, since most of the MPHs we have analyzed can be understood as instances of an article.

Articles are part of the set considered as determiners in Spanish. Spanish has two classes of articles: definite and indefinite. Definite articles have two different forms in the singular: el ‘the’ (masculine), la ‘the’ (feminine).4 Masculine and feminine articles have plural forms: los ‘the’ (masculine) and las ‘the’ (feminine). There are also two contracted words formed by a preposition and the article el: al (a + el) and del (de + el). Excepting these contracted forms, definite articles are unstressed and proclitic, phonologically-dependent grammatical elements. Indefinite articles have two different forms for each gender in the singular (masculine un ‘a, an’, feminine una ‘a, an’) and two forms in the plural (masculine unos ‘some’, feminine unas ‘some’).

The D is the head of the determiner phrase (DP). The D agrees with the noun (N) in gender and number. The N has two genders, masculine and feminine, and two numbers, singular and plural. This is a rather complex system in which not all nouns have two genders or two numbers; it depends on the specific N. Adjectives (As) agree with Ns in gender and number and they are organized in a system with two genders (masculine and feminine) and two numbers (singular and plural).

1.1.2. Monosyllabic Place Holders in L1 Acquisition of Spanish

Primary Research Works

The research by López Ornat et al. (1994) was the first study on MPHs in the L1 acquisition of Spanish, where they referred to MPHs as amalgamas or unidades-no-analizadas (amalgams or non-analyzed units). An example appears in (4):

| 4. | Aópa | ||

| (a | ópa) | ||

| MPH FEM-SING | [r]opa N FEM-SING | ||

| ‘The clothes.’ | (Ángela, 1;9; taken from López Ornat et al. 1994, p. 116) | ||

They considered that acquisition could be broken up into four phases: (1) a pregrammatical phase from ages 1;6 to 2;0, in which children imitate and do not make mistakes; (2) a phase from ages 2;0 to 2;6 where children omit mandatory grammatical marks or make mistakes in the selection of grammatical marks; (3) a phase from ages 2;6 to 3;00, with overgeneralized rules; and (4) a phase from ages 3;0 to 3;6, with flexible rules. A two-word stage in the first phase has been documented, in which children produce two-word outputs with an ambiguous meaning. Children learning Spanish produce amalgams of articles + nouns in this two-word stage, a stage in which a pre-placed sound coming from the unstressed article appears.

Aguirre Martínez (1995) agreed with Bottari et al. (1993–1994) in the idea that the placement of MPHs implies the discovery of the position in which determiners are generated in adult language and in the fact that the non-systematic appearance of these forms can be due to performance factors. She proposed the term “formas comodín” (“wildcard forms”).

In the framework of the Minimalist Program and research about the relationship between MPHs and feature typology, we can find works by Bartra (1997) and Lleó (2003). Bartra (1997) studied the appearance of a neuter vocalic element schwa in certain contexts in child language acquisition and gives this element a crucial linguistic status because this protoclass, which expresses an interpretable feature, can be considered as the realization of the feature [+referential], a precursor to the complement and D. By contrast, Lleó (2003) argued that these vowels (which are not always schwa according to her, but more often [a] and [e]) activate not only interpretable features, such as definition, but also non-interpretable features, such as gender. Lleó (2003) considered that gender was the first feature acquired, at least at the same time as definition; the difference between singular and plural appears early but not before the difference of gender. The reason for the early acquisition of gender consists, according to her, in “morphophonetic transparency”, because many masculine nouns in Spanish end with –o and many feminine nouns end with –a. She proposed that these filling syllables are differentiated in two ways: (1) into protoarticles or definite and indefinite articles; and (2) into masculine and feminine gender.

As Liceras (2002) pointed out, Bartra’s hypothesis is not substantially different from the hypothesis defended by López Ornat (1997), although they subscribe to different theoretical frameworks. López Ornat (1997), from a constructivist point of view, proposed the existence of a pregrammatical system which projects some “amalgamas prenominales” (“prenominal amalgams”) or phonoprosodic forms of vN (vowel + noun) and vV (vowel + verb), which are precedents of a full grammatical category. López Ornat’s (1997) research was based on data from María’s longitudinal output (from the ages of 1;7 to 2;1) and looked for phonoprosodic features which distinguish pre-nominal phrases (pre-NPs) from pre-verbal phrases (pre-VPs): the pre-NP phonoprosodic form would include a gender feature. According to her, the change from the pregrammatical representation to the grammatical one is supported by phonoprosodic knowledge and grows gradually through these elements—non-morphological outputs that work as primitive NPs (or pre-NPs) which will turn into NPs and join together phonological materials from articles and nouns. The process from the use of pre-NPs to grammaticalization is made up of three stages (not four, as was claimed in López Ornat et al. (1994)); the first and second stages are considered pregrammatical, while in the third one they are considered as a linguistic structure. These stages are 0N, vN and bare NP (without adjectives, pronouns, neuter case, nor ambiguous nouns). The sequence vN, which is the one we are addressing here, maintains the grammatically correct word order within the NP and differentiates the masculine and feminine values to a great extent.

Vowels and Features

Researchers do not agree regarding the timbre of the vowels in Spanish MPHs. Aguirre Martínez (1995) claimed that most vowels are [a], but Mariscal (1997) claimed that children prefer [e] and other vowels like [a]. Lleó (2003) argued that vowels were more [a] and [e] than [ә]. Torrens and Wexler (2001), in their research about children with specific language impairments (SLI) learning Spanish and Catalan, showed that these children used [ә] instead of articles.

Another point of controversy among researchers is the consistency in the use of vowels and its relationship with gender. Some researchers (Bottari et al. 1993–1994; Liceras et al. 2000) coincided in the idea that there is no consistency in the selection of the vowel, at least at the beginning. Liceras et al. (2000) considered that the unstressed vowels found in child language are MPHs which do not agree at the beginning with the nouns they precede and gradually become [a] for feminine and [e] for masculine. These MPHs constitute, for them, the proof that children learning Spanish activate the non-interpretable feature [word marker/gender] typical of nouns, adjectives, and determiners (Bernstein 1993). This is in contrast to the proposal of Bartra (1997) who suggested the activation of an interpretable feature in logical form, that is to say, their semantic content [+referential]. According to Liceras et al. (2000), the activation of the feature [+word marker/gender] is a process which is only explicit in the mother tongue because adults, as with many children acquiring an L2, rarely share the intuition of child L1 learners. However, as we will propose later in this article (see Section 3.1.1), our data show that children acquiring Spanish as an L2 use these MPHs too. López Ornat (1997), on the contrary, stated that these forms include a gender-specification feature with vowel consistency.

Mariscal (2001) did not find a clear relationship between vowels and the gender of the noun they accompany, and she pointed out that there are individual preferences in favor of some forms or others. She studied the acquisition process of NPs in Spanish through experimental data of four children aged under three (from 1;10 to 2;07). The data she analyzed showed that these vowels are randomly combined with masculine and feminine nouns and they gradually adjust to adult articles and other determiners; children alternate the use of pe, epe, ope, and (a/e) pe (instead of el/un pez o pez ‘fish’). She claimed that acquisition of all categories is a gradual process in which, as acquisition moves forward, variability decreases. This gradual process had an intermediate stage of vowels preceding nouns in three of the four children, following the stage of determiner omissions and occurring before the stage of the full realization of determiners. Gender and definition are realized in different ways depending on each child.5 These filling syllables, according to her, are early forms that approach articles but are phonologically underspecified; the production of these forms is a type of phonoprosodic bootstrapping. The acquisition of the determiner category would be produced gradually: first, the position and some phonological features are acquired, and then phonetic, morphological and semantic details.

As Tolchinsky et al. (2003) pointed out, the claim by Mariscal (2001) reinforces the previous existence of the position that MPHs and determiners are to fill, which supports in fact the idea of an innate pattern. The only data that could prove, for them, the fact that the category is not acquired, would be the appearance of the lexical forms fulfilling the category determiner in a position forbidden by the category (that is, an N appearing linearly before a D), but this datum has never appeared. This datum would have the form of (5):

| 5. | Mesa | a |

| N FEM-SING | MPH FEM-SING | |

| table | the | |

| ‘The table.’ | ||

Prosody of Monosyllabic Place Holder

The prosodic aspect of MPHs is another main issue being discussed. The phonoprosodic hypothesis defended by Mariscal (2001) was also defended by Veneziano and Sinclair (2000), who explained the appearance of MPHs on the basis of the role of phonology and prosody and suggested that these vocalic elements appearing in the first child outputs are the result of an organization of the phonoprosodic regularities of the language. Children add a vocalic element in order to reach the iambic pattern of the kind vowel, consonant, vowel (consonant) in which the first vowel is occupied by the MPH.

Lleó and Demuth (1999) and Lleó (2003) also defended the prosodic bootstrapping hypothesis, the idea that prosody facilitates the way to syntax and triggers syntactic structures. Lleó (2003) considered that protoarticles provided the necessary syllables to complete the binary foot; the abundant individual differences found in the use of MPHs could be based on the morphoprosody of the target language.

Serra and Sanz (2003) also addressed the prosodic aspect of the MPHs. They studied the Serra-Solé corpus and this vocalic element schwa, which coexists in child language with adult-like forms of articles, prepositions and auxiliaries; these forms appear, according to them, not only in the substitution of one category but of two or more. These elements can be considered an articulatory or fluency fill, an element with a prosodic cause and not exclusively a protogrammatical vocalic element because they can be found in children aged between 12 and 24 months, with a tendency to be located at the beginning of the melodic sentence.

Monosyllabic Place Holders and Their Relationship with Noun-Drop

Noun-drop (N-drop) constructions are DPs without an overt N but in which the D and A agree with the null N, asin (6):

| 6. | la | [Ø] | roja |

| ART FEM-SIN | N FEM SIN | A FEM-SIN | |

| the | [Ø] | red | |

| ‘The red one.’ | |||

The relationship between MPHs and N-drop was studied by Liceras et al. (2000), who analyzed the data from Magín and María (L1 Spanish) and Adil and Madelin (child L2 Spanish in a natural context). These data had been partially analyzed by Liceras et al. (1998b) and Rosado (1998). Liceras et al. (2000) propose that MPHs were incompatible with N-drop in L1 acquisition, where a relationship between the feature [+word marker/gender] and N-drop seems to be found. This statement is the result of an empirical observation and also the logical consequence of the theories by Snyder and Senghas (1997) and Snyder et al. (1999). According to Snyder and Senghas (1997) and Snyder et al.’s (1999) proposals, N-drop constructions appear in child L1 data when checking the morphological realization of gender in determiners is possible and, specifically, after the appearance of vowel [a] in this grammatical category. If MPHs constitute precisely the stage previous to the morphological realization of gender and number in determiners, they seem to be incompatible with Noun-drop (N-drop).

Liceras et al. (2000) tried to demonstrate that MPHs disappear when the feature [+word marker/gender] is projected. In the L1 data analyzed, the gender disagreements in N-drop constructions (this is to say, the use of e with feminine nouns and a with masculine nouns) stop appearing at age 2;1, which shows, in their views, that children do not use these vowels as gender markers in the first stages of acquisition but as MPHs; as soon as children project DPs the abstract feature [+word marker/gender] is assigned. They did not find any cases of MPHs in N-drop constructions with adjectival phrases (APs) (although one e in Magín was found before age 2;00) nor any cases with prepositional phrases (PPs) and complementizer phrases (CPs). It looks like children drop MPHs in order to project a DP which incorporates the feature [+word marker/gender]; when this feature is activated in the L1, gender disagreements stop. No direct relationship between the acquisition of the DP paradigm in L2 Spanish and N-drop is found according to Liceras et al. (2000). We should retain this proposal, which will be incorporated in the discussion about the results of our study (see Section 3.1.3).

1.2. Monosyllabic Place Holders in L2 Acquisition of Spanish

As can be appreciated in the previous section, MPHs have been extensively studied in the L1 acquisition of Spanish. By contrast, the study of MPHs in the acquisition of Spanish as an L2 has not received as much attention. Nevertheless, some works can be found comparing the L1 and L2 (child and adult) acquisition of Spanish.

Regarding child L2 acquisition, Liceras et al. (1998a) and Rosado (1998, 2000) analyzed L1 and L2 Spanish data (L2 data collected in natural and institutional contexts) and studied N-drop with complements such as AP, PP and CP, as well as MPHs. One of the main differences between L1 and L2 acquisition, as claimed by Liceras et al. (1998a), is the appearance of MPHs in L1 but not in L2. Rosado (2000), on the contrary, located two MPHs in the child L2 data she studied, and she considered they might constitute “anecdotal examples”. The instances are (7) and (8):

| 7. | a | rosas | |

| MPH FEM-SING | N FEM-PL | ||

| ‘The roses.’ | (taken from Rosado 2000, p. 74) |

| 8. | o | gorro | |

| MPH MAS-SING | N MAS-SING | ||

| ‘The hat.’ | (taken from Rosado 2000, p. 74) |

However, this work shows examples that contradict Rosado’s claim, given that several MPH cases can be drawn up in our corpora, both for Rachida and Khalid (see Section 3.1.1).

Rosado (2000) also studied data from two children learning Spanish as a foreign language in Canada and she located some MPHs. She considers that these MPHs do not share their “nature” with the MPHs found in L1 acquisition, but these forms come from the L2 these children have already learnt, French. These children used the forms a and e (the same forms as children learning Spanish as an L1) but also some forms that she thinks were taken literally from French (le ‘the’, son ‘his, her’…) or that have been formed with elements from French and Spanish (lel ‘French the + Spanish the´, tun ‘Spanish you + French a?’…). Most of these forms agree in gender with the noun they precede, as in (9) and (10):

| 9. | A | Cuabeza | |

| MPH FEM-SING | cabeza N FEM-SING | ||

| ‘A head.’ | (taken from Rosado 2000, p. 86) | ||

| 10. | lel | león | |

| MPH? MAS-SING | N MAS-SING | ||

| ‘The lion.’ | (taken from Rosado 2000, p. 86) | ||

Liceras et al. (2000) also proposed that one of the main differences between L1 and L2 data is the absence of MPHs in L2. According to them, the reason resides in the fact that children learning an L2 have a phonological sophistication that does not allow them to process the input in the same way as child L1 learners. This could explain the fact that L2 learners do not mark Spanish DPs with the feature [+word marker/gender], in contrast to L1 speakers.

Another significant difference that can be found between L1 and L2 acquisition in children is related to N-drop and the acquisition of the determiner paradigm in Spanish. Liceras et al. (2000) did not find many instances of N-drop constructions in L2 and some of them were not correct.

There are few works in the literature about the acquisition of Spanish DPs in adults. In the adult acquisition of Spanish, Liceras et al. (1998b) proposed that the acquisition of gender markers cannot be clearly related to the appearance of N-drop.

Rosado (2007) studied the acquisition of clitics and articles by adults learning Spanish as a foreign language and speaking English and French as mother tongues, and adults learning Spanish as a second language and speaking a Chinese dialect as a mother tongue. She did not find any MPHs in those data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

This research about MPHs is part of a broader study of DPs in two children acquiring Spanish as an L2 and speaking Dariya or Moroccan Arabic as an L1. The corpora containing the data from both children, Rachida and Khalid, were formed by two longitudinal corpora based on semi-spontaneous production data elicited via interviews carried out by us over 16 months, using a number of drawings or illustrated tales. Drawings were provided by the director of the study, Juana M. Liceras, and were used previously in the project “The specific nature of non-native grammar and the principles and parameters theory” (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRCC), project #410-96-0326 (1996–1999)).

Our corpus comprises 49 interviews of between 15 and 30 min each. Interviews were conducted in two periods separated by the summer holidays: the first period was from 26 January 1999 to 17 June 1999; and the second period was from 19 October to 16 May 2000. In total, 11 interviews were recorded in the first period for each child; in the second period 14 interviews were recorded with Khalid and 13 with Rachida (one less due to the girl’s absence). According to the information provided by the Santiago Ramón y Cajal School (Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain) where the recordings were made, both children had just arrived in Spain when the recording sessions began. The director of the school, the children’s parents and both children gave their oral consent to make the recordings.

Rachida was born in Morocco on 20 April 1988; she was aged 10;9 when the research began and 12;00 when it ended. Her mother tongue was Moroccan Arabic, and she also had some knowledge of French. According to the director of the school, she had just arrived in Spain when the interviews began. In accordance with the Moroccan school system, a child of her age would have studied two or three years of classical Arabic (basic level) and a year of French (very basic level) (ElKadiri and Nicolás 2015).

Khalid was born in Morocco on 20 March 1992, and he was aged 6;10 when the research began and 8;1 when it ended. His mother tongue was Moroccan Arabic and he had just arrived in Spain when the recordings began. He would have not had any formal education in classical Arabic or French while in Morocco (ElKadiri and Nicolás 2015).

2.2. Methodology

The use of longitudinal corpora with semi-spontaneous production is a methodology with two main advantages, as pointed out by Unsworth (2005): (1) it is an activity that the participants are familiar with and which is exclusively based on spoken language (something more accurate for children); and (2) it requires a focus on the content and not the form, so that children are careful with what they say and not how they say it. The clear disadvantage of this methodology is the fact that sometimes the data collected can be minimal or not significant. This risk is minimized when the linguistic phenomenon analyzed is very productive in the spoken language, such as for DPs. It should not be forgotten than longitudinal studies are designed with the idea of providing data that can show a change in the use of the phenomenon and, eventually, allow for the establishment of stages in the acquisition process. In our opinion, the methodology we chose is successful in these two senses, with respect to productivity and graduation: the number of DPs was high enough as to allow us to make significant inferences, and data have shown changes in the process of acquisition of the Spanish DP and the elements that comprise it.

All interviews were transcribed and codified in CHAT format from CHILDES (MacWhinney 2000), and frequencies of use were calculated with CLAN.6Interview recordings are available through TalkBank (MacWhinney 2007).7 A coded version, that includes morphological codes developed by the author, is also available upon request.

2.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

The different ages of the two children (10;9 for Rachida, and 6;10 for Khalid at the beginning of the data collection) allowed us to investigate the role of age in the process and attainment of acquisition. Our research has the added benefit, on the one hand, that there are very few studies dealing with the similarities and differences between L1 acquisition and child L2 acquisition and, on the other hand, that there are no data available with this child L1–child L2 combination.

In a broader study concerning the acquisition of DPs in these children (Nicolás 2016) we compared our child L2 data on the acquisition of Spanish DPs with (1) L1 acquisition data; (2) data from children with a SLI; (3) L2 acquisition data from other children; and (4) adult L2 acquisition data. Our research questions focused on three areas: (1) the role of previous linguistic experience and the importance of L1 transfer; (2) the acquisition of DP features and the acquisition of gender and number in Ds, Ns and As; and (3) the role of age in the acquisition of the DP (the difference between child and adult L2 acquisition) and final attainment. The study of MPHs is related to two of these research questions: the role of age in the acquisition of DPs and the acquisition of DP features. Other hypotheses were related to the relationship of MPHs with gender agreement within the DP, N-drop constructions are what we call prosodic nominal assemblies (PNAs).

● Question 1. MPHs and the role of age in the acquisition of DPs

Regarding the role of age in the acquisition of DPs, we defended the idea that the process of acquisition of DPs in Khalid (who was aged 6;10 at the beginning of our research and 8;1 at the end) went through similar stages to those of children acquiring Spanish as an L1, which was not the case of Rachida (who was 10;9 at the beginning of our research and 12 at the end). Thus, we assumed that, in the case of Khalid, the acquisition process would be similar to that found in children learning Spanish as an L1, while we would not find this kind of process in Rachida.

This hypothesis was based on the difference in age between Khalid and Rachida, which supported the idea that Khalid’s acquisition process was a non-native child’s acquisition process, while Rachida’s acquisition process was a non-native adult’s acquisition process.8 Many proposals have been made about the age of the critical period, that is to say, the age in which it is considered that non-native adult language acquisition begins. Some researchers have put the upper limit at no more than 10 years of age, Krashen (1973) proposed 5 years; DeKeyser (2000) and Johnson and Newport (1989) proposed 7; Bialystok and Miller (1999), Schwartz (2004), Unsworth (2005)9and Meisel (2008) agreed to fix 8 years of age as the limit;10 Penfield and Roberts (1959) put the limit at 9; and Hulk and Cornips (2005) suggested a period from 4 to 7 years of age. Other researchers, such as Long (1990) and Lenneberg (1960, 1967) think that the critical period is more extended. Long proposed 15 years of age, and Lenneberg suggested the period of puberty as an upper limit.11 Therefore, we assume that Rachida (aged 10;9) went through an adult language acquisition process and Khalid (aged 6;10) went through a child language acquisition process. Johnson and Newport (1989, 1991) and DeKeyser (2000) also provide support for our claim, since they state that children learning an L2 before the age of 8 years can be classified in the group of native speakers in several tasks related to some syntactic phenomena.

● Question 2. MPHs and the acquisition of DP features

The L2 acquisition of morphology in children has been addressed from two opposite points of view, which can be illustrated with the research works carried out by Schwartz (2004) and Meisel (2008). Meisel (2008) claimed that in the morphological domain, the language-acquisition process of a child learning an L2 is similar to the acquisition of adults learning an L2 and different from the acquisition of native children. In contrast, Schwartz (2004) stated that in the syntactic domain, the acquisition of children learning an L2 is similar to the acquisition of adults learning an L2, while in the morphological domain the acquisition of children learning an L2 is similar to the acquisition of native children.

Following Schwartz (2004) in this case, we consider that the process of acquisition of morphology in Khalid follows that of a non-native child’s language-acquisition process similar to that of children acquiring Spanish as an L1. Therefore, we assumed we would find intermediate morphological stages in Khalid that were only typical features of native acquisition and not of adult acquisition, such as MPHs or what we call PNAs (see Section 3.3). We hypothesized that we would find a substantially larger number of MPHs in Khalid than in Rachida (if she had any at all). In order to corroborate this statement, we analyzed all the examples of MPHs in both children.

Another hypothesis related to this question was that phonological distinctions in the L2 can be available to non-native children, who can analyze Spanish phonetics as native children do, and not to adults. In this way, the definite article, an unstressed and enclitic element in Spanish, can be joined with the noun in a sole morphological unit, generating MPHs as well as PNAs. However, we should take into account the fact that some researchers state that the phonological critical period appears very early. For example, Long (1990), proposed 6 years of age, that is to say, prior to the age of Khalid when he was first exposed to Spanish.

● Question 3. MPHs and gender agreement within the DP

Following Liceras et al. (2000), who studied the link between MPHs and N-drop in L1 acquisition, we considered that a relationship could be documented between the use of MPHs and the feature [+word marker/gender]. We proposed that MPHs constitute a first stage of acquisition in L2 in which the gender feature was gradually being activated. When the feature [+word marker/gender] was completely activated, both MPHs and gender mismatches among the elements of the DP stop appearing: MPHs were gradually being replaced by the correct morphology of the determiners and gender errors linked to the DP elements were disappearing. We understood this relationship between the feature [+word marker/gender], on the one hand, and MPHs and gender agreement within the DP, on the other hand, as a gradual process in which the boundaries among different stages cannot always be clearly delimited.

This hypothesis could be verified if we could prove that gender mistakes in the DP were directly proportional to MPHs.

● Question 4. MPHs and N-drop constructions

Liceras et al. (2000), following Snyder and Senghas (1997) and Snyder et al. (1999), stated that if MPHs constitute the stage previous to the morphological realization of gender and number in Ds in L1 acquisition, they should be incompatible with N-drop (see MPHs and their Relationship with Noun-Drop in Section 1.1.2). The referent of N should be recovered through the gender and number features of D; if D does not have a gender feature, the N-drop structure should not be allowed. MPHs should disappear when the feature [+word marker/gender] is projected. However, no direct relationship was found between the acquisition of the DP paradigm in L2 Spanish and N-drop.

We proposed, as it was mentioned in the previous question, that a gender feature could be found in some MPHs because the feature [+word marker/gender] is gradually being activated in L2 acquisition. Therefore, we assumed that MPHs could be compatible with N-drop constructions in L2 acquisition.

● Question 5. MPHs and Prosodic Nominal Assemblies

Our last question and hypothesis were associated with PNAs, a phenomenon which has not been studied previously and which will be analyzed in Section 3.3. Given the fact that both MPHs and PNAs seem to represent an earlier stage in the overall acquisition of Ds, we proposed that all of them would appear in the same stage of the acquisition process. Consequently, our previous discussion about the use of MPHs in Questions 1 and 2 could be extended to the use of PNAs.

3. Results

3.1. Monosyllabic Place Holders: Occurrences and Features

3.1.1. Number of Occurrences

The total number of MPHs we found in our corpora was not very large for any of the children, but it was slightly higher in Khalid’s corpus (24 instances) than in Rachida’s corpus (16 instances). We did find a substantial difference between the children in the temporal extent of these MPHs, which appeared in Rachida for the last time in interview 12 (at age 11;5) while, by contrast, an MPH was found in interview 24 in Khalid (at age 8;1). It should be noted that we found MPH instances instead of definite and indefinite articles.

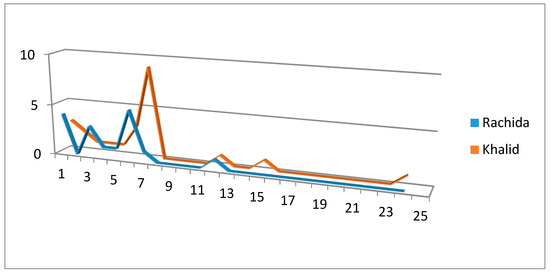

A graph of the appearance of MPHs in Rachida and Khalid’s corpora is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Number of occurrences of monosyllabic place holders (MPHs).The horizontal axis represents interview numbers; the vertical axis represents numbers of occurrences.

This graph evidences two facts: (1) there were not many differences between the children; and (2) both children shared the same pattern: most of the occurrences were found in the first period of the corpora (the first 11 interviews) and decreased with time.

On one hand, our hypothesis that MPHs should be more numerous in Khalid’s corpus than in Rachida’s corpus is not supported by these data (Question 2, Section 2.3). In this regard, we should accept that the difference of age between Rachida and Khalid cannot support the idea that each child represents a different type of language acquisition (adult and child, respectively), at least with the data provided by their use of MPHs (Question 1, Section 2.3). On the other hand, the pattern found in both corpora is noteworthy: most of the interviews contained between one and seven instances, with a peak around the sixth and seventh interviews. On this point we should remember the hypothesis pointed out by Liceras et al. (1998b): children stop using MPHs to project a DP with the feature [+word marker/gender]; when this feature is activated, gender disagreements stop appearing. This hypothesis can be verified if we are able to prove a directly proportional relationship between gender mismatches and MPHs (see Question 3, Section 2.3 and Section 3.1.3).

3.1.2. Data per Vowel Timbre

A review of the vowels accounted for in Rachida’s corpus shows that MPHs were mainly [a] (6 instances) and [e] (6 instances), as in (11) and (12), even though we found some other forms that seemed to attain the characteristics of MPHs, such as [i]12 (2 instances), as in (13) and (14), and [o] (2 instances), as in (15) and (16):

| 11. | A | espada | ése… | es del niño |

| A MPH FEM-SIN | N FEM-SIN | DEM MAS-SIN | ||

| The | sword | this | is from the boy | |

| ‘This sword is from the boy.’ | (Rachida, 10;11) | |||

| 12. | Eto | e | rey | de marroquino |

| DEM NEUT | MPH MAS-SIN | N MASC-SIN | ||

| This | the | king | of Morocco (?) | |

| ‘This, the King of Morocco.’ (?) | (Rachida, 10;9) | |||

| 13. | E | i | rey | |

| E[s] COP 3ª P SIN | MPH MAS-SIN? | N MAS-SIN | ||

| Is | the | king | ||

| ‘He is the king.’ | (Rachida, 10;9) | |||

| 14. | i | Paloma | |

| MPH MAS-SIN? | N FEM-SIN | ||

| the | dove | ||

| ‘The dove.’ | (Rachida, 10;10) | ||

| 15. | INV: ¿De qué color está vestida? (INV: Which color is she dressed in?) | |||

| O | rosa | |||

| MPH MAS-SIN | A FEM-SIN | |||

| the | pink | |||

| ‘In pink.’ | (Rachida, 10;10) | |||

| 16. | Son | o | libros | |

| COP 3ª P PL | MPH MAS-SIN | N MAS-PL | ||

| are | the | books | ||

| ‘They are the books.’ | (Rachida, 10;11) | |||

In Khalid’s corpus, 11 instances of [a], 8 of [e], 2 of [o], and 2 of [u] were located, as well as an instance in which the vowel was accompanied by a plural morpheme (17):

| 17. | as | piedras | |

| MPH FEM-PL | N FEM-PL | ||

| the | stones | ||

| ‘The stones.’ | (Khalid, 8;1) | ||

The use of vowels was inconsistent in many cases in both corpora, as can be inferred from examples (18)–(21) from Khalid’s corpus, in which the same noun appeared with different vowels, even in the same interview:

| 18. | a | ratón | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | mouse | ||

| ‘The mouse.’ | (Khalid, 7;1) | ||

| 19. | e | rató | |

| MPH MAS-SIN | rató[n]N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | mouse | ||

| ‘The mouse.’ | (Khalid, 7;1) | ||

| 20. | a | papel | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | paper | ||

| ‘The paper.’ | (Khalid, 7;1) | ||

| 21. | e | papel | |

| MPH MAS-SIN | N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | paper | ||

| ‘The paper.’ | (Khalid, 7;1) | ||

The vowel timbre was sometimes overtly discordant with the noun gender, as in (22) and (23) with feminine nouns and in (24)–(29) with masculine nouns. This second type has a more widespread use in Rachida’s corpus, which conforms to the direction of gender mistakes in the determiners in this corpus.

| 22. | e | boca | |

| MPH MAS-SIN | N FEM-SIN | ||

| the | mouth | ||

| ‘The mouth.’ | (Khalid, 6;10) | ||

| 23. | e | Navidad | |

| MPH MAS-SIN | N FEM-SIN | ||

| the | Christmas | ||

| ‘The Christmas.’ | (Rachida, 10;9) | ||

| 24. | a | niño | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | boy | ||

| ‘The boy.’ | (Rachida, 10;11) | ||

| 25. | a | sol | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | sun | ||

| ‘The sun.’ | (Rachida, 10;11) | ||

| 26. | a | caballo | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | horse | ||

| ‘The horse.’ | (Rachida, 10;11) | ||

| 27. | a | papel | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | paper | ||

| ‘The paper.’ | (Rachida, 10;11) | ||

| 28. | a | rojo | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | A MAS-SIN | ||

| the | red | ||

| ‘The red one.’ | (Khalid, 6;11) | ||

| 29. | a | hermano | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | brother | ||

| ‘The brother.’ | (Khalid, 7;1) | ||

The vowel timbre is occasionally the same as the article with which the noun agrees, being definite or indefinite, as in (30)–(33):

| 30. | e | gorro | |

| MPH MAS-SIN | N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | hat | ||

| ‘The hat.’ | (Rachida, 10;10) | ||

| 31. | a | espada | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | N FEM-SIN | ||

| the | sword | ||

| ‘The sword.’ | (Rachida, 10;11) | ||

| 32. | u | gato | |

| MPH MAS-SIN | N MAS-SIN | ||

| the | cat | ||

| ‘The cat.’ | (Khalid, 6;10) | ||

| 33. | a | chica | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | N FEM-SIN | ||

| the | girl | ||

| ‘The girl.’ | (Khalid, 7;1) | ||

3.1.3. Features

The instance in (32) could suggest that MPHs are not always strictly vocalic elements appearing in the position of determiners before they appear with all their morphological realizations, but they are more like phonetic approaches to a given morphological realization of a D, whether they are definite or indefinite. The lack of phonetic concretion of these MPHs is supported by the fact that they are unstressed elements in which the vowel timbre is precisely the most prominent part of the determiner and, therefore, the most recognizable and reproducible part.

Regarding the gender features of MPHs, we agree with Liceras et al. (1998b) in the hypothesis that when the feature [+word marker/gender] is activated, gender disagreements stop appearing (Question 3, Section 2.3). This hypothesis could be verified if we can prove that gender mismatches are directly proportional to MPHs. The analysis of gender disagreements in DPs in both corpora supports this claim. Some brief notes about the gender feature in the Dariya DP can be useful at this point in order to determine the potential impact of transfer: definite articles have no gender in Dariya (al or a ‘the’) and indefinite articles are formed with the definite article and the form of the numeral one placed after N (Herrero 1999); Ns and As have two gender features (masculine and feminine).

The number of gender mistakes in Ns and As was low, especially in Khalid’s corpus (in both periods) and also in Rachida’s (mainly in period 2). In the first period, gender mistakes made by Rachida in Ns and articles do not show a definite direction (masculine instead of feminine or feminine instead of masculine) beyond what would be expected at random. Contrary to Ns and As, both children made many gender mistakes in Ds, a fact that could be expected if we considered the transfer from Dariya. However, these mistakes were not in the direction we predicted (masculine instead of feminine) but on the contrary (feminine instead of masculine). In period 1, this trend was statistically significant: χ2(1) = 15.38, p<0.001, in Rachida, and χ2(1) = 60.84, p<0.001, in Khalid. In the second period, the number of gender mistakes was lower for both children and there were no significant differences in the direction of mistakes; χ2(1) = 0.62, p = 0.431, in Rachida; and χ2(1) = 1.60, p = 0.206, in Khalid.

Therefore, we can conclude that the statistical significance of gender mistakes in Ds coincides with the appearance of MPHs, which can constitute evidence of the relationship between MPHs and gender agreement: at the same time that gender mismatches stop being significant, MPHs cease to appear. Nevertheless, we should take this conclusion with caution since the concurrence of two facts can show that they are related but the co-appearance can also be due to chance.

3.2. Monosyllabic Place Holders and Noun-Drop

In L1 and L2 child language-acquisition data of Spanish analyzed by Liceras et al. (2000), they found a unique instance of MPH with N-drop with an adjectival phrase (an e in Magín’s data), before age 2;0. However, four instances can be located in our corpora: two in Khalid’s corpus, and two in Rachida’s corpus. Instances (34) and (35) are repeated here and analyzed more carefully; they show N-drop constructions with APs. Instances (36) and (37) show N-drop constructions with PPs.

| 34. | INV: ¿De qué color está vestida? (INV: Which color is she dressed in?) | |||

| O | [color] | rosa | ||

| MPH MAS-SIN | N MAS-SIN | A MAS-SIN | ||

| the | [color] | pink | ||

| ‘In pink.’ | (Rachida, 10;10) | |||

| 35. | a | [Ø] | rojo | |

| MPH FEM-SIN | N MAS SIN | A MAS-SIN | ||

| the | [Ø] | red | ||

| ‘The red one.’ | (Khalid, 6;11) | |||

| 36. | INV: ¿Qué libros te gustan más de los que tienes? (INV: Which books do you like the most of the ones you have?) | |||

| E | [libro] | de matemáticas | ||

| MPH MAS-SIN | N MAS-SIN | PP | ||

| the | [book] | of Maths | ||

| ‘The book of Maths.’ | (Rachida, 11;5) | |||

| 37. | INV: ¿Qué María? (INV: Which María?) | |||

| E | [profesora] | de música | ||

| MPH MAS-SIN | N FEM-SIN | PP | ||

| the | [teacher] | of Music | ||

| ‘The teacher of Music.’ | (Khalid, 7;6) | |||

Only these four instances have been located in our corpora. The instances in (35) and (37) show a mismatch between the vowel of the MPH and the vowel we could expect if D appears in its full morphological realization. We do not consider that these four instances are anecdotal since we have found two different kinds of complements in N-drop constructions and the instances are located in both corpora. It looks like N-drop constructions are compatible de facto with MPHs in L2 acquisition (Question 4).

3.3. Monosyllabic Place Holders and Prosodic Nominal Assemblies

We propose the term prosodic nominal assemblies (PNAs) to name the phonetic amalgams formed by a definite article and a noun beginning by a vowel, in which the article is joined to the noun in a proclitic way. By contrast with MPHs, where the vowel is the part of the D which remains in place, in PNAs the consonant is the part of the D which is joined to the N. Monosyllabic Place Holders and PNAs share the feature of being the heads of phrases, even if their morphological realizations are not target-like, and constitute evidence of the learning process that leads to the acquisition of free morphology.

In Rachida’s corpus, 16 instances of PNAs were found, while in Khalid’s corpus only 2 instances were found. Khalid’s instances were very scarce but this could not be considered anecdotal since this supported a trend shown by Rachida’s instances. These PNAs appeared in Rachida’s and Khalid’s corpora with singular Ns, both masculine and feminine, as in (38) and (39), and with plural nouns, as in (40):

| 38. | Labuelo | ||

| [el | abuelo] | ||

| [ART DEF MAS-SIN | N MAS-SIN] | ||

| [the | grandfather] | ||

| ‘The grandfather.’ | (Rachida, 10;9) | ||

| 39. | Lotro | ||

| [el | otro] | ||

| [ART DEF MAS-SIN | A MAS-SIN] | ||

| [the | other] | ||

| ‘The other.’ | (Khalid, 7;11) | ||

| 40. | Lárboles | ||

| [los | árboles] | ||

| [ART DEF MAS-PL | N MAS-PL] | ||

| [the | trees] | ||

| ‘The trees.’ | (Rachida, 10;11) | ||

These PNAs or confluences in a prosodic unit of a definite article—always phonetically realized as [l]—and an N seem to be of the same nature as MPHs; this is to say, they represent an earlier stage in the overall acquisition of articles (and other Ds) in which children are aware of the position occupied by articles and are sensitive to some parts of the phonetic realization of articles but not to all parts.

On accepting the importance of phonetic imitation in the development of MPHs, we could agree that a relationship can be established between MPHs and PNAs (Question 5, Section 2.3). The data of our corpora showed, as seen in Section 3.1.1, that no significant differences were documented in reference to MPHs in either of the children. Therefore, we could hypothesize that a comparison between the use of PNAs in both children should offer a similar conclusion.

Nevertheless, the average proportion of PNAs was significantly higher in Rachida than in Khalid (participant effect) F(1.45) = 7.72, p = 0.010, η2p = 0.138. The time effect was not significant: F(1.45) = 2.72, p = 0.106, η2p= 0.057. However, these effects were moderated by a significant interaction between participant and time: F(1.45) = 7.53, p = 0.009, η2p= 0.143. The majority of the production of PNAs in Rachida appeared in period 1, while both children showed similar proportions of PNAs during period 2.

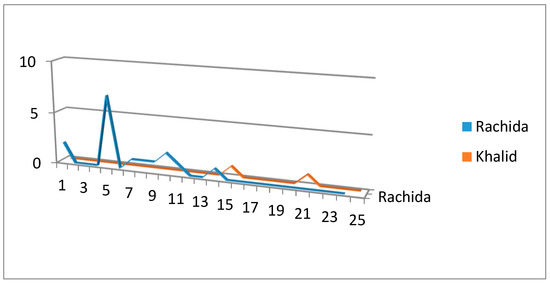

A graph of the appearance of PNAs is provided Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Number of occurrences of prosodic nominal assemblies (PNAs).The horizontal axis represents interview numbers; the vertical axis represents numbers of occurrences.

PNAs were only documented in the initial stages of acquisition in these corpora and not in the most advanced ones. The pattern of appearance of these PNAs coincided with the pattern found in MPHs (see Section 3.1.1). This fact could suggest that during the initial stages of both L1 and L2 acquisition children try to approach the phonetics of the language they are learning. Later on, when phonetic analyses are more appropriate (and perhaps with the assistance of writing and reading skills), morphological instances become more adequate.

4. Conclusions

This article has focused on the use of MPHs in the acquisition of Spanish. MPHs have been analyzed extensively in L1 acquisition of Spanish but their study in L2 acquisition has received much less attention. This study provides evidence for the presence of MPHs in the L2 Spanish of two L1 Moroccan Arabic children living in Spain: Rachida, who was aged 10;9 when the data started to be collected and Khalid, who was aged 6;10 when the research began.

The data documented in our corpora showed that MPHs are used by both children (see Section 3.1.1). The analysis of MPHs in Rachida and Khalid’s corpora does not confirm the hypothesis formulated in Questions 1 and 2 (Section 2.3). We stated that the different age of the two children would imply that Khalid would use MPHs in the same way as native children do, and that Rachida would not. However, and even though the number of occurrences of MPHs is slightly higher in Khalid’s corpus (24 instances) than in Rachida’s corpus (18 instances), the difference is not significant.

We acknowledge that these data do not provide evidence for the hypothesis that each child represents a different type of language acquisition (adult L2 and child L1), as we initially defended. On the contrary, both children seem to use MPHs as native children do. Our data are also in accordance with the data documented by Rosado (2000) about MPHs found in foreign language acquisition in children. Our work showed that MPHs are found in child L2 acquisition of Spanish, regardless of the child’s age. Given the fact that the presence of MPHs has been previously detected in L1 acquisition of Spanish and in child foreign language acquisition of Spanish, the results of our work can support the hypothesis that the use of MPHs may be a strategy available to all child learners of Spanish.

The use of MPHs by Rachida and Khalid shows a pattern in which most MPHs appear in the first period of the corpora and disappear as time goes by. The patterns located in the use of MPHs may suggest that the feature [+word marker/gender] is involved in their appearance, as suggested by Liceras et al. (2000): as MPHs cease to appear, gender mismatches stop being significant (see Section 3.1.3). The analysis of gender disagreements in DPs in our corpora supported this claim: the statistical significance of gender mistakes in Ds coincides with the appearance of MPHs. However, as we mentioned in Section 3.1.3, this conclusion should be taken with caution since the concurrence of two facts does not necessarily imply that they are related.

We also studied the relationship between MPHs and N-drop (see Section 3.2). Four instances of N-drop constructions with MPHs have been documented in our corpora. These instances have been found in both corpora and with two different kinds of N-drop constructions: with APs and PPs. Therefore, we argue that these instances are not anecdotal and that N-drop constructions are not incompatible de facto with MPHs, in contrast to the proposal by Liceras et al. (2000) for L1 Spanish, who use Snyder and Senghas (1997) and the theoretical framework of Snyder et al. (1999).

A relationship between MPHs and PNAs seems to be supported by the data we have analyzed; MPHs and PNAs both seem to be phonetic approaches to the correct morphological realizations of Ds and Ns (see Section 3.3). The pattern of appearance of PNAs coincides with the pattern of appearance of gender mistakes within the DP and the pattern of appearance of MPHs: all of them are left aside by children as acquisition progresses.

More data analyses are needed if we are to determine whether these trends are followed by all children acquiring Spanish as an L2 and to elucidate whether these facts can be applicable to all types of language acquisition by children.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to the Guest Editors of this Special Issue for their confidence and support, to the Languages Editorial Office for their continuous assistance and to the two anonymous reviewers, whose comments were very helpful.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| A | Adjective |

| ART | Article |

| COP | Copulative verb |

| CP | Complement Phrase |

| D | Determiner |

| DEF | Definite |

| DEM | Demonstrative |

| FEM | Feminine |

| L1 | First Language |

| L2 | Second Language |

| MAS | Masculine |

| NP | Nominal Phrase |

| MPH | Monosyllabic Place Holder |

| N | Noun |

| NEU | Neuter |

| P | Person |

| PL | Plural |

| PNA | Prosodic Nominal Assembly |

| PP | Prepositional Phrase |

| SING | Singular |

| VP | Verbal Phrase |

References

- Abney, Steven P. 1987. The English Noun Phrase and Its Sentential Aspect. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre Martínez, María del Carmen. 1995. La Adquisición de las Categorías Gramaticales en Español. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Bartra, Anna. 1997. The schwa as a functional joker in early grammars. Paper presented at the Incontro di Grammatica Generativa, Pisa, Italy February 1997, and the VII Colloquium on Generative Grammar, Oviedo, Spain, April 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Judy. 1993. The syntactic role of word markers in null nominal constructions. Probus 5: 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen, and Barry Miller. 1999. The problem of age in second-language acquisition: Influences from language, structure and task. Bilingualism Language and Cognition 2: 127–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bley-Vroman, Robert. 1990. The logical problem of foreign language learning. Linguistic Analysis 20: 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bottari, Piero, Paola Cipriani, and Anna Maria Chilosi. 1993–1994. Prosyntactic devices in the acquisition of Italian free morphology. Language Acquisition 3: 327–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeKeyser, Robert M. 2000. The robustness of critical period effects in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 22: 499–533. [Google Scholar]

- Demonte, Violeta. 1999. El adjetivo: Clases y usos. La posición del adjetivo en el sintagma nominal. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Directed by I. Bosque and V. Demonte. Madrid: Espasa Calpe, pp. 129–215. [Google Scholar]

- ElKadiri, Houmad, (CEOSI), Estrella Nicolás, and (Fundación José Ortega y Gasset-Gregorio Marañón). 2015. Personal communication.

- Eguren, Luis. 1989. Algunos datos del español en favor de la hipótesis de la frase determinante. Revista Argentina de Lingüística 5: 163–203. [Google Scholar]

- Eguren, Luis. 2006. La capacidad explicativa de la Hipótesis de la Frase Determinante. Revista Iberoamericana 17: 215–38. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero Muñoz-Cobo, Bárbara. 1999. Gramática de Árabe Marroquí Para Hispano-Hablantes. Almería: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Almería. [Google Scholar]

- Hulk, Aafke, and Leonie Cornips. 2005. Differences and similarities between Child L2 and (2)L1: DO-support in Child Dutch. In Proceedings of the 7th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA 2004). Edited by Laurent Dekkydtspotter, Rex A. Sprouse and Audrey Lijestrand. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 163–77. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Jaqueline S., and Elisse Newport. 1989. Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology 21: 60–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Jaqueline, and Elisse Newport. 1991. Critical period effects on universal properties of language: The status of subjacency in the acquisition of a second language. Cognition 39: 215–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmiloff-Smith, Annette. 1979. A Functional Approach to Child Language. A Study of Determiners and Reference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krashen, Stephen D. 1973. Lateralization, language learning and the critical period: Some new evidence. Language Learning 23: 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laca, Brenda. 1999. Presencia y ausencia de determinante. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Directed by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa Calpe, pp. 891–928. [Google Scholar]

- Lenneberg, Eric H. 1960. Language, evolution, and purposive behaviour. In Culture in History: Essays in Honor of Paul Radin. Edited by Stanley Diamond. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lenneberg, Eric H. 1967. Biological Foundations of Language. New York: Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti, M. 1999. El artículo. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Directed by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa Calpe, pp. 787–890. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, Juana M. 2002. The L1/L2 ‘Fundamental Difference Hypothesis’ revisited: More on the interpretation of acquisition data. Paper presented at the 6th Hispanic Linguistic Symposium, Iowa City, IA, USA, 18–20 October. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, Juana M., Elisa Rosado, and Lourdes Díaz. 1998a. On the differences and similarities between primary and non primary language acquisition: Evidence from Spanish null noun. Paper presented at EUROSLA’98, Paris, France, 10–12 September. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, J. M., Elena Valenzuela, Elisa Rosado, and Lourdes Díaz. 1998b. The role of morphological paradigms in the acquisition of syntactic knowledge: N-drop and null subjects in L1 and L2 Spanish. Paper presented at 28 Kabgyage Symposium in Romance Linguistics (LSRL), University Park, PA, USA, 16–19 April. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, Juana M., Lourdes Díaz, and Caroline Mongeon. 2000. N-Drop and determiners in native and non-native Spanish: More on the role of morphology in the acquisition of syntactic knowledge. In Current Research on the Acquisition of Spanish. Edited by Ronald P. Leow and Cristina Sanz. Somerville: Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lleó, Conxita. 1997. Filler syllables, proto-articles and early prosodic constraints in Spanish and German. In Proceedings of the GALA’97 Conference on Language Acquisition. Edited by Antonella Sorace, Caroline Heycock and Richard Shillcock. Edinburg: The University of Edinburgh, pp. 251–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lleó, Conxita. 2001a. The interface of phonology and syntax: The emergence of the article in the early acquisition of Spanish and German. In Approaches to Bootstrapping: Phonological, Lexical, Syntactic and Morphophysiological Aspects of Early Language Acquisition. Edited by Jürgen Weissenborn and Barbara Höhle. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins, vol. 2, pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lleó, Conxita. 2001b. The transition from prenominal fillers to articles in Spanish and German. In Research on Child Language Acquisition:Proceedings of the 8th International Congress of the IASCL. Edited by Margareta Almgren, Andoni Barreña, María-José Ezeizabarrena, Itziar Idiazabal and Brian MacWhinney. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, vol. 2, pp. 713–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lleó, Conxita. 2003. Hacia la gramática minimista, maximizando lo prosódico. Cognitiva 15: 169–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleó, Conxita, and Katherine Demuth. 1999. Prosodic constraints on the emergence of grammatical morphemes: Crosslinguistic evidence from Germanic and Romance Languages. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Boston Conference on Language Development. Edited by Annabel Greenhill, Heather Littlefield and Cheryl Tano. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, vol. 3, pp. 407–18. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Michael H. 1990. Maturational constraints on language development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 12: 251–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Ornat, Susana. 1997. What lies in between a pre-grammatical and a grammatical representation? Evidence on nominal and verbal form-function mappings in Spanish from 1;7 to 2;1. In Contemporary Perspectives on the Acquisition of Spanish, Volume I: Developing Grammars. Edited by Ana Teresa Pérez-Leroux and William R. Glas. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- López Ornat, Susana, Almudena Fernández, Pilar Gallo, and Sonia Mariscal. 1994. La Adquisición de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk, 3rd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2007. The TalkBank Project. In Creating and Digitizing Language Corpora: Synchronic Databases. Edited by Joan C. Beal, Karen P. Corrigan and Hermann L. Moisl. Houndmills: Palgrave-Macmillan, pp. 163–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mariscal, Sonia. 1997. El proceso de Gramaticalización de las Categorías Nominales en Español. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Mariscal, Sonia. 2001. ¿Es “a pé” equivalente a Det + N? Sobre el conocimiento temprano de las categorías gramaticales. Cognitiva 13: 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisel, Jurgen M. 2008. Child second language acquisition or successive first language acquisition. In Current Trends in Child Second Language Acquisition.A Generative Perspective. Edited by Belma Haznedar and Elena Gavruseva. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolás, Estrella. 2016. La Adquisición del Sintagma Determinante en Español por Niños de Lengua Materna Árabe Marroquí. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. Available online: http://eprints.ucm.es/39529/1/T37867.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Penfield, Wilder, and Lamar Roberts. 1959. Speech and Brain Mechanisms. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Ann M. 1983. The Units of Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Ann M. 1985. Language segmentation: Operating principles for the analysis and perception of language. In The Crosslinguistic Study of Language Acquisition. Edited by Dan Slobin. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum, vol. 2, pp. 1029–68. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Ann M., and Lise Menn. 1993. False starts and filler syllables: Ways to learn grammatical morphemes. Language 69: 742–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Academia Española. 2009. El artículo (I). Clases de artículos. Usos del artículo determinado. In Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa Libros, pp. 1023–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rosado, Elisa. 1998. La Adquisición de la Categoría Funcional Determinante y los Sustantivos Nulos del Español Infantil. Master’s thesis, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Rosado, Elisa. 2000. La Adquisición Infantil del Español. Una Aproximación Gramatical. Málaga: ASELE. [Google Scholar]

- Rosado, Elisa. 2007. La Adquisición del Sintagma Determinante en Español Como Lengua Segunda y Lengua Extranjera. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Bonnie D. 2004. Why child L2 acquisition? In Proceedings of Generative Approaches to Language Acquisiton 2003. Edited by Jaqueline van Kampen and Sergio Baauw. Utrecht: LOT Occasional Series, pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, Miquel, and Mònica Sanz. 2003. Acotando la sobreextensión de ‘gramática’ y de otros términos lingüísticos. Comentarios a ‘Caminando hacia la gramática: una perspectiva teórica’ de Mireia Llinàs. Cognitiva 15: 221–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, William, and Ann Senghas. 1997. Agreement morphology and the acquisition of noun-drop in Spanish. In Proceedings of the 21th Annual Boston University Conference of Language and Development. Edited by Elizabeth Hughes, Mary Hughes and Annabel Greenhill. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, vol. 2, pp. 584–91. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, William, Ann Senghas, and Kelly Inman. 1999. Agreement Morphology and the Acquisition on Noun Drop in Spanish. Manuscript: University of Connecticut-Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- Tolchinsky, Liliana, Melina Aparici, and Elisa Rosado. 2003. Caminando con la gramática. Cognitiva 15: 235–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrens, Vincent, and Kenneeth Wexler. 2001. Specific Language Impairment in Spanish and Catalan. Aloma 9: 131–48. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, Sharon. 2005. Child L2, Adult L2, Child L1: Differences and Similarities. A Study of the Acquisition of Direct Object Scrambling in Dutch. Utrecht: LOT. [Google Scholar]

- Veneziano, Edy, and Hermine Sinclair. 2000. The changing status of filler syllables on the way to grammatical morphemes. Journal of Child Language 27: 461–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | A list of abbreviations is provided in the back matter. |

| 2 | These numbers stand for the age of children: the first is the number of years; the second, months, and the third, days. Therefore, 1;9,26 means 1 year, 9 months and 26 days. This notation is used throughout the article. |

| 3 | The issue of whether possessives belong to the category of Ds is disputed. Abney (1987) considers that they are specifiers of an empty D because they cannot license an empty N, despite the morphological variability. |

| 4 | A neuter gender feature can be found in articles and other Ds in Spanish but its use is rather complex since Ns cannot be neuter. An example of a demonstrative with a neuter gender feature can be found in (12). |

| 5 | The existence of these individual differences is one of the reasons why she argues against the idea of an acquisition process guided by innate patterns of behavior. She also claims that through continuist generative grammar it is understood that an output such as a pé is the combination of a D and N and, therefore, the theory confers adult syntactic categories to child language, which is not justified. |

| 6 | CHILDES is the child language component of the Talkbank system, a system for sharing and studying conversational interactions, which is available on the web. CHAT is the format used in corpora’s interviews in the Talkbank system, which are analyzed through the CLAN program. |

| 7 | Corpora transcripts and recordings are available at http://talkbank.org/access/SLABank/Spanish/Nicolas.html. |

| 8 | However, it should be noted that variability is a feature of stages of the acquisition process, even in native acquisition, where not all children follow the same path (Peters 1983). |

| 9 | Unsworth (2005), in particular, considers that at most four grammatical principles are in place. |

| 10 | In fact, Meisel (2008) prefers a second stage, the age of seven, since he considers that choosing an earlier age is more convenient methodologically. He also points out that the age of the critical period is not the same for syntax, morphology, and phonology; he proposes that the age limit for morphology and syntax is between three and four years of age. Therefore, according to him, the acquisition process in Khalid could have been classified as non-native adult acquisition since the boy was aged over four. |

| 11 | After the critical period, some researchers (Bley-Vroman 1990) postulate that L2 acquisition is accomplished through general problem-solving processes and not through linguistic procedures. |

| 12 | According to Herrero (1999), Moroccan Arabic has three vocalic phonemes: /a/, /ə/ and /o/; [i] and [e] are allophones of /ə/, while [o] and [u] are allophones of /o/; the pronunciation of /a/ goes from [a] to [æ]. This could perhaps explain these uses of [i]. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).