Abstract

Language ideologies about gendered linguistic behaviour are crucial in shaping expectations and metapragmatic judgements on politeness. This study focused on how gender and language ideologies reinforce normative assumptions about the relationship between gender and (im)politeness and at the same time influence individuals’ perception of (im)politeness. Based on data collected from 251 respondents through online questionnaires administered between July 2024 and January 2025, the study investigated whether certain linguistic choices tend to be stereotypically associated with a particular gender and if the same utterance is evaluated differently depending on whether it is attributed to a man or a woman. Participants’ responses revealed systematic associations between linguistic forms and perceived gender, indicating that direct requests were more often linked to male speakers, while indirect or mitigated forms were associated with female speakers. Findings also showed that in 17 out of 19 cases, the same utterance was rated as more polite when attributed to a woman, suggesting that among Russian-speaking participants politeness was not only expected from women but also more readily perceived in their speech, reinforcing existing gender ideologies and stereotypes.

1. Introduction

Language ideologies concerning the relationship between language use and gender appear to be one of the most influential lenses through which linguistic behaviour is normatively framed, interpreted, and evaluated within a given culture or community. What is considered polite or appropriate in speech is often filtered through socially constructed representations and expectations related to gender. These ideologies shape beliefs about how men and women speak or are expected to speak, often reinforcing the idea that gendered linguistic differences are natural and fixed. Based on this view, female speech tends to be stereotyped as cooperative, polite, and emotionally expressive, as opposed to male speech, seen as more assertive, referential, and dry. Such dichotomies, exemplified in Tannen’s (1990) distinction between rapport-talk and report-talk, reflect broader societal norms that associate femininity with relational and supportive communication and masculinity with a direct and content-oriented style.

At the same time, these ideologies can be to varying degrees internalised by individuals, resulting in what Cameron (2003, p. 463) describes as a self-fulfilling prophecy. Embodying these linguistic stereotypes by adopting and reiterating normative and expected speech behaviours in interaction constitutes a form of social positioning in interaction (Bucholtz & Hall, 2005), a way of identifying with and being recognised within a particular social identity (Bailly, 2009).

This study explored existing linguistic gender stereotypes in Russian and their effect on the perception of linguistic (im)politeness. It aimed to identify individuals’ preconceptions about the relationship between gender and politeness, including commonly held assumptions about gendered patterns in language use. Additionally, it examined whether politeness perception is influenced not only by linguistic forms but also by the presumed gender of the speaker. Specifically, the paper addresses the following research questions.

- Do certain linguistic choices tend to be associated with a particular gender in Russian? What are the common preconceptions about men’s and women’s speech behaviours related to the linguistic expression of politeness?

- Do gender stereotypes tend to affect people’s perception and evaluation of linguistic (im)politeness? Is the same request evaluated differently depending on whether it is imagined to have been said by a man or a woman?

Positioned at the intersection between sociolinguistics and pragmatics, the study focused on the emic understanding of (im)politeness—what has been defined as metapragmatic politeness1 (Eelen, 2001) or first-order politeness (Watts, 2003). Eelen (2001, p. 35) describes metapragmatic politeness1 as “instances of talk about politeness as a concept, about what people perceive politeness to be all about”. In line with the so-called third wave of politeness research (Kádár & Haugh, 2013), lay conceptualisations of politeness are viewed as central to understanding how politeness is socially understood and negotiated across multilingual and multicultural settings (Ogiermann & Blitvich, 2019). This perspective is especially relevant in the case of Russian, spoken across a wide range of multilingual contexts, and where, as Rathmayr (1999) shows in her metapragmatic study on politeness1, speakers articulate their understandings of politeness in ways that do not always align with universalist models (e.g., Brown & Levinson, 1987). In the present study, attention was paid not only to how politeness is discussed, recognised, and evaluated by native or proficient users of Russian, but also to how perceptions of (im)politeness intersect with gender expectations and stereotypes.

To investigate these issues, two questionnaires were administered online to a total of 251 Russian-speaking respondents. Both questionnaires included a set of 19 requests and prompts to action derived from the annotated transcripts of two corpora of Russian spoken language: ‘One day of speech’ (Odin Rechevoy Den’) and ‘The speech of Muscovites’ (Rech’ Moskvichey). As part of the experimental design, the selected utterances were slightly adapted to remove any explicit gender cues. The first questionnaire was administered to 125 participants, who were asked to read each sentence, determine the speaker’s gender, and rate its degree of politeness on a scale from 1 to 5. The second questionnaire, completed by another group of 126 participants, focused only on politeness evaluation. Thus, the only difference between the questionnaires was that the second one did not contain any questions about speakers’ gender, allowing for a comparison between potentially biased judgements and more neutral ones.

The experiment was designed to test the following hypotheses.

- Participants will tend to systematically associate certain request formulations with either male or female speakers, reflecting internalised expectations and assumptions about gendered politeness norms. In particular, direct, more concise, and unsoftened request formats will tend to be attributed to male speakers, while indirect and mitigated requests will more frequently be attributed to female speakers.

- The same utterance will be rated as more polite when imagined to be produced by a female speaker than when attributed to a male speaker, reflecting the stereotype that women are more polite than men in interaction.

The hypotheses were based on previous, albeit limited, research on gender and language in Russian (Zemskaya et al., 1993; M. H. Mills, 1999; Garanovich, 2020), which outlined a set of features reflecting stereotypes and folk-linguistic ideas about male and female speech in Russian interaction. Stereotypically male speech is assumed to be direct, concise, and content-oriented. It tends to be described as more logically structured and focused on the efficient transmission of information, with minimal reliance on emotional or evaluative language. Moreover, it is more likely to feature slang, coarse, or non-standard vocabulary. In the case of requests, it is assumed to rely on brief, straightforward formulations, typically using imperatives that are either unmitigated or exhibit only a minimal degree of mitigation. Stereotypically female speech, by contrast, is seen as more polite, cautious, verbose, and attentive to interpersonal dynamics. It is commonly associated with the use of evaluative and emotionally expressive language, stance and discourse markers, repetitions, backchanneling, and cooperative overlap. In addition, it is believed to include more hesitation markers, fillers, hedging, and vague language, which reduce assertiveness and directness. Thus, stereotypically female requests are typically characterised as less categorical and imposing, often formulated indirectly, preferring interrogative or declarative formats over unmitigated imperatives. These are typically accompanied by a range of mitigation strategies, such as the use of diminutives, politeness formulas, expressions of gratitude and apologies, provision of reasons and justifications, as well as modal constructions and conditional clauses.

While systematic research on linguistic gender stereotypes in Russian remains limited, the hypotheses were further informed by findings from studies on languages other than Russian (cf. Section 2 and Section 3) and by experimental research in cognitive social psychology discussing stereotype assimilation effects (Biernat & Sesko, 2018), which shows how gender stereotypes can bias linguistic perception, evaluation, and memory.

In order to contextualise this study, the following section outlines the conceptual foundations of gender ideologies and linguistic gender stereotypes, discussing how they are constructed, reinforced and transmitted through and in relation to language and social structures.

2. Gender Ideologies and Gender Stereotypes: A Theoretical Overview

Since the first groundbreaking work on language and gender (Key, 1975; Lakoff, 1975; Thorne & Henley, 1975), the field has significantly expanded, becoming increasingly more interdisciplinary and incorporating insights from psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, pragmatics, linguistic anthropology, and discourse studies. These approaches have moved beyond essentialist accounts of systematic gender-based differences in speech and static models of male dominance and female deficiency (Thimm et al., 2003, p. 530), extending the focus to the dynamic ways in which speakers actively perform, negotiate, and co-construct gender in interaction (Butler, 1990; Bucholtz & Hall, 2005). At the same time, scholars continue to explore the influence of social norms, structural inequalities, gender ideologies, and stereotypes on language practice (Thimm et al., 2003; Talbot, 2003; Coates, 2015; Cameron, 2014; Tabassum & Nayak, 2021).

Gender stereotypes refer to socially and culturally shaped beliefs or preconceptions about the attributes, preferences, and behaviours typically ascribed to women and men, including expectations regarding their social conduct and social roles (Kirilina, 1999; OHCHR, 2014). Generally, they operate through processes of simplification and exaggeration (Talbot, 2003), reducing individuals to a limited set of traits presumed to characterise entire social groups, which are foregrounded at the expense of individual variations. According to Talbot (2003, p. 472), gender stereotypes are intertwined with gender ideologies and serve to reinforce them. If, on the one hand, stereotypes serve a cognitive and representational function (Lippmann, 1922)—making the world simpler and predictable with minimum effort—on the other hand, they are not merely descriptive. Functioning as ideological tools, they create social expectations and dictate how individuals should behave and perceive other people’s behaviour, often in accordance with normative and naturalised gender roles. As early as 1978, the Belgian academic and social psychologist Willem Doise proposed a multilevel framework for analysing social phenomena, situating social stereotypes at the intersection of cognitive, social, and ideological structures. He identified four distinct, but interconnected levels of analysis within a given society: a first level of social images in individual cognitive processing; a second level focused on interpersonal representations shaped through interaction; a third level of collective representations that reflect the structural relations and positions between social groups; and a fourth level concerned with ideologies and broader belief systems. In his view, stereotypes are primarily situated at the third level as forms of collective representations that mirror the relations and asymmetries between social groups. At the same time, they are actualised through individual cognitive processes (level one), mediated by the dynamics of interpersonal interaction (level two), and ultimately embedded in broader ideological systems (level four) (Doise, 1978, p. 55).

These collective ideological representations are formed, reinforced, and transmitted through key institutions such as family and education (Lomova, 2004) and most importantly through media and mass communication (Ward & Grower, 2020). Language functions as the primary medium in this process, as stated by Scheller-Boltz (2020, pp. 75–76), who underlines the importance of language in creating, expressing, and reinforcing social stereotypes. However, he argues that language is not inherently oppressive; rather, it is the language community that uses it to sustain dominant ideologies and power structures.

The relationship between language and stereotypes involves not only the transmission of stereotypes through language but also the stereotyping of language use itself, particularly in relation to gendered linguistic traits and behaviours. Culturally rooted beliefs about how men and women speak or should speak and how specific linguistic choices are viewed as masculine or feminine reflect normative expectations about how each gender is expected to use language. For instance, Cameron (1995) notes that women have often been the primary targets of what she terms verbal hygiene, meaning the ideological efforts to correct or regulate language to make it align with an idealised standard. Moreover, as discussed by S. Mills (2003) in her influential book titled Gender and Politeness, based on the stereotypical assumption that women display their vulnerability and subordination in interaction, their linguistic behaviour has often been described as cooperative and deferential. Not surprisingly, politeness has come to be directly associated with femininity and regarded as a specifically female concern (S. Mills, 2003, p. 203). Female speech has frequently been characterised as indirect and marked by the use of emotionally evaluative terms, vague intensifiers, discourse markers, fillers, and politeness strategies such as hedging and mitigation. Men’s linguistic behaviour, on the other hand, has been defined as direct, assertive, and at times even aggressive and rude.

Kiesling (2003, pp. 509–510) distinguishes between social action norms and social group norms, clarifying how certain linguistic choices come to be consistently associated with a particular gender. Social action norms refer to the social meanings that linguistic forms are given in interaction; for instance, mitigation devices can signal politeness and deference. Social group norms instead regulate how such meanings are linked to speakers’ identities; for example, politeness and deference are linked to femininity. Through this two-step association, a linguistic feature like mitigation comes to index femininity, not because of any intrinsic connection emerging from language itself, but because of repeated, ideologically grounded patterns of social practice and language use. As a result, the link between form and gender acquires both descriptive and prescriptive force. This also highlights the importance of viewing linguistic gender stereotypes not in isolation from broader social stereotypes. In fact, they reflect and reproduce dominant ideologies and expectations about men and women as social actors (Garanovich, 2020). In turn, these beliefs can shape how individuals’ speech is perceived, encoded, and evaluated. From a cognitive perspective, stereotypes operate as filters that guide perception and even memory (Biernat & Sesko, 2018), making expected behaviours, such as a man interrupting or a woman smiling politely, more likely to be noted and remembered than behaviours that contradict such expectations.

The following section provides an overview of experimental studies that have explored the relationship between language and gender, with a particular focus on attitudes towards male and female speech.

3. Empirical Research on Linguistic Gender Stereotypes

Attitudes and perceptions of gendered language use have been investigated through empirical studies, particularly within Anglo-American research, since the 1970s. This research has laid the groundwork for exploring linguistic gender stereotypes. A foundational contribution is Kramer’s (1977) investigation into stereotyped beliefs about male and female speech among American high school and university students. Participants were asked to rate a set of 51 speech characteristics, and the results showed that several traits were judged as distinguishing male and female speech. Although the study did not focus specifically on politeness, many of the speech traits perceived by participants as differentiating male and female speech were also distinctive features of (im)politeness. Among these traits were, for example, concern for the listener, gentle speech, and polite speech, which were judged as characteristics of female speakers, in contrast to use of swear words, authoritarian speech and aggressive speech, associated with male speakers. Similar findings emerged in Berryman and Wilcox (1980), who presented participants with messages identical in content, but written in either a male- or female-typed style. Participants’ attributions of personality and social traits varied notably according to the perceived gender of the speaker.

More recent studies have explored how stereotypes shape individuals’ evaluations of language use and users. Particularly relevant is the matched-guise experiment conducted by Lindvall-Östling et al. (2020), which investigated how gender stereotypes influence the perception of conversational styles. Their findings showed that despite the speech content being the same, participants perceived the digitally manipulated male voices as more dominant and interruptive than the female voices, which were judged as more attentive and patient.

Nonetheless, the intersection of gender stereotypes, (im)politeness, and perception is marginally addressed in the existing literature and needs further investigation. The gap becomes even more evident when shifting focus from English-language studies to research on Russian. Considering that, as pointed out by Zemskaya et al. (1993) and M. H. Mills (1999), Russian exhibits deeply rooted norms and expectations surrounding male and female speech styles, these issues are particularly relevant to explore.

One study that explicitly engaged with these questions is the experiment conducted by Plyusnina (2012), who identified which linguistic features of written texts were marked as gendered in Russian speakers’ consciousness. For instance, male participants tended to interpret texts with abstract nouns, neologisms, and metaphorical language as written by a woman, while female participants attributed a text to a man when it contained negative evaluative vocabulary, technical terms or slang, coarse or confrontational tone, direct argumentation, and a strong authorial presence. Another significant contribution is the study by Garanovich (2020), which, through associative experiments combining sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic methods, investigated how gender stereotypes are structured in the linguistic consciousness of Russian speakers and vary across different social groups. The study confirmed the salience of stereotypical associations linking, for example, male speech to dominance, brevity, and rationality and female speech to emotionality, politeness, verbosity, and a lack of argumentative force, mirroring stereotypically gendered personality traits. Moreover, by showing how these associations differed depending on participants’ gender, age, and educational and professional background, Garanovich also demonstrated that stereotypes are shaped not only by broad societal expectations, but to an even greater extent by the specific communicative norms internalised by particular social groups.

Other studies have addressed specific linguistic stereotypes in Russian speech, for example, the association of diminutives with women or obscene language with men. In a survey conducted among male and female students, Andrews (1999) found that they perceived diminutives as more characteristic of female speakers, particularly in familial roles such as mothers and grandmothers. The frequent use of diminutives by women is not merely a stylistic tendency, but reflects broader cultural associations with emotional warmth and intimacy. Lucchetti (2021) focused instead on obscene language and attitudes towards it. The results of her questionnaire showed that actual usage rates of obscene language among male and female participants were comparable, challenging the common assumption that this is predominantly a male linguistic behaviour in Russian. Nevertheless, female respondents reported experiencing much stronger social judgement when cursing, especially in public. As a consequence, they framed their own use of vulgar language as inappropriate or potentially damaging to their social image, revealing internalised language ideologies that associate obscenity with masculinity and view its use by women as a violation of linguistic norms. Together, these studies demonstrate how language attitudes in Russian are shaped by strong gender ideologies and expectations.

Despite the growing interest in language attitudes and gender stereotypes in Russian linguistic research, there is still a significant gap in experimental studies investigating how politeness is influenced by (and evaluated through) them. The present study intended to address this gap.

4. Materials and Methods

This study employed an experimental design to explore linguistic gender stereotypes in Russian and their effect on the perception and evaluation of (im)politeness. The following subsections present the design and implementation of the experiment, as well as the demographic characteristics of the respondents.

4.1. Questionnaire Design

To investigate attitudes and existing stereotypes concerning men’s and women’s speech behaviours and the linguistic expression of politeness, a sociolinguistic experiment was carried out using online questionnaires. To minimise bias and avoid priming, the first questionnaire (henceforth Q1) was titled ‘The sociolinguistics of politeness’ and described in general terms. In the description, it was only mentioned that the purpose of the questionnaire was to study the perception of different linguistic formulations of requests and prompts to action and the evaluation of their degree of politeness, taking into account sociolinguistic factors. This section also indicated the estimated completion time and clarified that responses would be anonymous and used exclusively for scientific purposes.

The first section was designed to gather participants’ sociolinguistic profiles, including gender (male, female, non-binary), age (under 18, 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65 and above), country of residence, level of education (secondary education, incomplete higher education, bachelor’s degree or specialist diploma, master’s degree, PhD or higher), whether Russian was a native or foreign language, and other languages used on a daily basis.

The second part of Q1 contained 19 requests and prompts to action selected from the full-length transcriptions of two corpora of Russian spoken language: ‘One day of speech’ (Odin Rechevoy Den’) and ‘The speech of Muscovites’ (Rech’ Moskvichey).1 Both corpora, created to capture Russian spontaneous speech in different situations, consist of transcribed and annotated recordings of naturally occurring conversations. Despite the inherently more ‘chaotic’ nature of authentic speech data, their use in the questionnaire was essential for several reasons. First, contemporary research in the fields of pragmatics and discourse studies regards the use of natural data as a methodological advantage, as it allows a focus on real language practices rather than artificially constructed ones. Moreover, they minimise potential bias, as invented examples could inadvertently reflect the researcher’s own stereotypes or assumptions. Thus, this approach was intended to strengthen the ecological validity of the experiment by grounding this study of language attitudes in real-life language use.

These utterances were selected according to several criteria, partly informed by previous research in the field of language and gender in Russian (Zemskaya et al., 1993; M. H. Mills, 1999; Garanovich, 2020). The selection aimed to include specific linguistic features and diverse linguistic realisations of requests, varying in their degree of directness and mitigation. Utterances ranged from direct, imperative formats to more indirect, softened ones, and in certain instances, fully implicit prompts to action. Several utterances contained polite markers such as diminutives, softening lexical items, modal verbs, or hedging expressions, while others were formulated bluntly or even rudely and included colloquial and vulgar language. In addition, prosodic features such as hesitations, vocalised pauses, repetitions, and self-corrections were kept as in the original data. The selected speech fragments were carefully reviewed and where necessary minimally edited to remove explicit gender cues. It is important to mention that they were always presented in the same order to the participants.

For each utterance, Q1 included a multiple-choice question asking participants to guess the speaker’s gender among four options (‘woman’, ‘probably woman’, ‘probably man’, ‘man’) followed by a 5-point Likert-scale question to evaluate its degree of politeness, where 1 indicated ‘impolite’ and 5 ‘very polite’. These evaluations served to investigate the second question of the study, namely whether an identical communicative act is evaluated differently depending on the gender attributed to the speaker. To address this research question more precisely, an auxiliary questionnaire (henceforth Q2) titled “Evaluation of the degree of politeness” was created. It replicated the structure of Q1, but omitted any reference to the speakers’ gender, including only the 5-point Likert-scale question for each utterance. This allowed for a comparison between potentially biased evaluations of politeness and more neutral ones.

The final part of Q1 contained an open-ended question inviting participants to explain the criteria used in their responses. Since the previous questions were multiple-choice and did not include a neutral option for gender attribution, this space allowed respondents to express any reflections or additional considerations.2 For instance, they could clarify cases in which they felt constrained to choose one of the four available options despite believing that an utterance could have been produced by either a man or a woman or if they found the distinction irrelevant in all instances. To make this more explicit and complement the limitation of the multiple-choice questions, a multiple-selection box was also included. The available options were as follows:

- Women are generally more polite and tactful in communication than men.

- Men are generally more polite and tactful in communication than women.

- Women use less rude and obscene language.

- Women often use indirect, softened requests, while men more direct requests.

- Speech behaviour (including the use of polite/impolite forms, rude language, indirect formulations...) generally does not depend on gender, although some distinctive features and tendencies may sometimes appear.

- Speech behaviour (including the use of polite/impolite forms, rude language, indirect formulations...) does not depend on gender, but rather on subjective factors, inclinations, and personality.

These statements once again offered participants a way to indicate, for example, that they perceived speakers’ linguistic choices as independent of gender, even if previous questions forced them to attribute one gender to each utterance.

4.2. Respondents

A total of 251 participants took part in the study. The first group (n = 125) completed Q1, which included both gender attribution and politeness evaluation tasks. The second group (n = 126), serving as the control group, completed Q2, focused exclusively on politeness evaluation without any reference to gender. Both questionnaires were administered online via Google Forms between July 2024 and January 2025. Each was distributed to a different set of respondents through snowball sampling and social media platforms, primarily Facebook groups. While no inclusion criteria were applied, the questionnaires were intentionally shared within similar online communities and networks to target respondents with comparable demographic profiles. They were primarily shared on the pages of Russian-speaking communities residing in post-Soviet countries. Furthermore, given that the questionnaires were written in Russian and explored linguistic nuances likely inaccessible to users who were not highly proficient, they were addressed to individuals with native or near-native command of Russian.

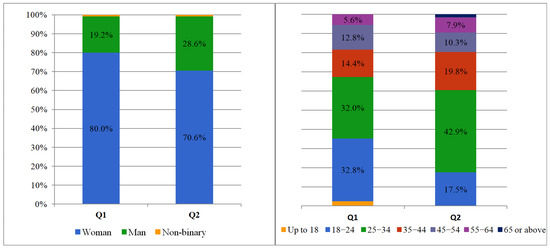

Regarding the demographic composition of the respondents, Figure 1 illustrates the gender and age distribution in the two questionnaires.

Figure 1.

Gender and age distribution in Q1 and Q2.

In both groups, the majority of participants consisted of women (80% in Q1; 70.6% in Q2), with only one non-binary respondent in each. Age distribution was also broadly comparable, although the main group included a higher proportion of respondents aged 18–24 (32.8% Q1; 17.5% in Q2), whereas the second group showed slightly higher representation in the ranges 25–34 (32% in Q1; 42.9% in Q2) and 35–44 (14.4% in Q1; 19.8% in Q2). Overall, both samples were predominantly composed of adults aged between 18 and 44. In terms of educational background, the majority of respondents in both samples reported holding higher-education qualifications, as shown in Figure 2.

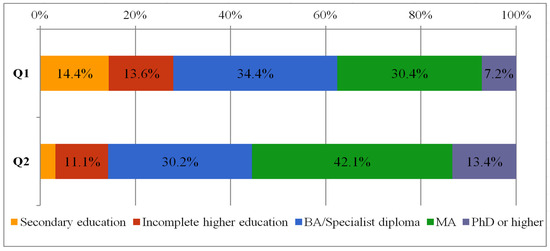

Figure 2.

Respondents’ educational background in Q1 and Q2.

It can be observed that over 70% of respondents in Q1 had completed a bachelor’s (34.4%), master’s (30.4%), or doctoral (7.2%) degree. Lower proportions had incomplete higher education or secondary education. In Q2, the proportion of participants with higher education was slightly higher (30.2%, 42.1%, and 13.4%, respectively), and a few had incomplete higher education or secondary education. Figure 3 shows the distribution of participants by country of residence in Q1 (on the left) and Q2 (on the right).

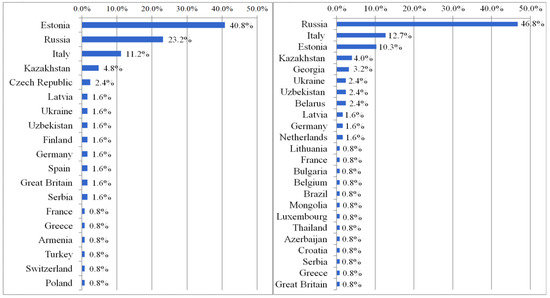

Figure 3.

Distribution of participants by country of residence in Q1 and Q2.

Participants of the main group were from 19 different countries, with the majority from Estonia (40.8%), Russia (23.2%), and Italy (11.2%). Other represented countries included Kazakhstan (4.8%), the Czech Republic (2.4%), a set of countries represented by two participants each (Latvia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Finland, Germany, Spain, Great Britain, and Serbia), and several countries with one participant each (France, Greece, Armenia, Turkey, Switzerland, and Poland). Among these, 89.6% considered Russian their native language (henceforth RNL), while 10.4%, based in Estonia (n = 5), Italy (n = 5), the Czech Republic (n = 2), and Poland (n = 1), considered it a second or foreign language (henceforth RFL).3

Respondents in the second group were from 24 different countries, partly overlapping with those in Q1, with the three main represented countries still being Estonia, Russia, and Italy. However, while respondents from Estonia were the majority in the main sample, this percentage was considerably smaller in the second group (10.3%). Other countries in Q2 included Kazakhstan (4%), Georgia (3.2%), Ukraine (2.4%), Uzbekistan (2.4%), Belarus (2.4%), and several other countries represented by one or two individuals each: Latvia, Germany, the Netherlands, France, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Belgium, Brazil, Mongolia, Luxembourg, Thailand, Azerbaijan, Croatia, Serbia, Greece, and Great Britain. As in the main group, the vast majority of respondents in Q2 (87.4%) identified Russian as their native language, while the remaining ones were proficient users of Russian as a second or foreign language. Including non-native speakers of Russian in the participant pool allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of how ideologies and stereotypes about gendered politeness norms circulate across different linguistic profiles within Russian-speaking communities. Moreover, it reflected the sociolinguistic reality of Russian as a language used across diverse multilingual settings, including the post-Soviet space, where multilingual speakers regularly engage with Russian pragmatic norms in everyday interaction. While this may have introduced a certain degree of variability in participants’ pragmatic competence, excluding individuals who, albeit not native speakers, actively use and negotiate Russian politeness norms would have meant disregarding a significant segment of the speech community under investigation. Potential differences in politeness evaluations provided by RFL users compared to those of RNL users were not interpreted as deviations from a native-speaker norm, but as part of the broader continuum of language ideologies shaped in multilingual environments.

It is worth noting that 80% of participants in Q1 and 74.6% in Q2 had a multilingual profile, using up to five languages on a daily basis. Figure 4 illustrates that Russian emerged as the most frequently used language daily (by 94.4% of participants in Q1 and 96% in Q2),4 followed by English (59.2% in Q1; 53% in Q2), Estonian5 (35.2% in Q1; 8% in Q2), and Italian (15.2% in Q1; 17.5% in Q2).

Figure 4.

Languages used on a daily basis by participants in Q1 and Q2.

Other languages spoken daily by respondents in Q1 included Ukrainian (8.8%), German (4.8%), French (4%), Spanish (3.2%), Finnish (2.4%), Polish, Czech, Romanian (1.6% each), and Latvian, Lithuanian, Greek, Chinese, Georgian, Uzbek, Armenian, Turkish, Japanese, and Kazakh (0.8% each). Beyond the languages mentioned in the first sample, additional languages reported in Q2 included Dutch, Belarusian, Tajik, Portuguese, Bulgarian, Arabic, Serbo-Croatian, Tatar, Mongolian, Kyrgyz, and Abkhaz. Given the diversity of linguistic profiles among participants, some variation in pragmatic competence and politeness interpretation was expected not only between RNL and RFL users, but also across the wider sample.

5. Results

The following two subsections present the results of the experiment. The first focuses on participants’ inferences about the speaker’s gender in each transcribed speech sample, discussing the emerging patterns and stereotypes about gendered language use and politeness in Russian requests. The second addresses participants’ evaluations of politeness and examines whether the same utterances were perceived differently depending on the presumed gender of the speaker.

5.1. Participants’ Guesses on Speakers’ Gender

To facilitate the analysis of participants’ responses, the prompts are reorganised here according to specific analytical criteria, namely shared linguistic and pragmatic features, as well as marked patterns in gender attribution. In the two questionnaires, they were presented in a randomised order, which was the same for all participants.

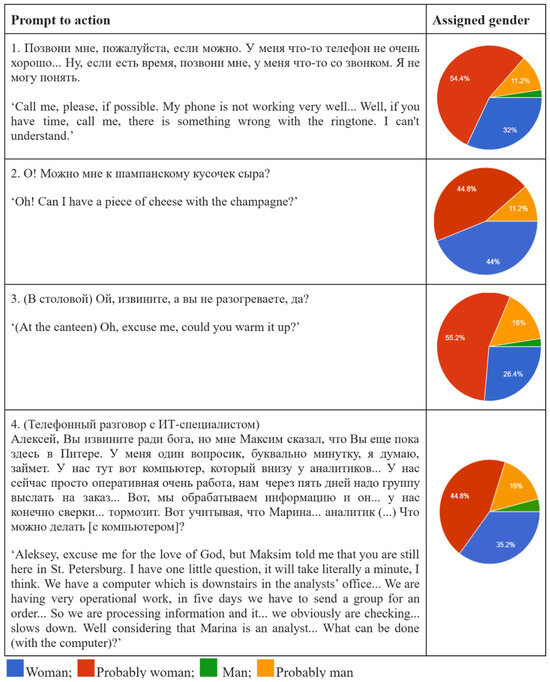

The first group includes the four requests that had the strongest association with female speakers and were rated the most polite in both questionnaires, with an average politeness rating ranging from 3.8 to 4.4 on a 5-point scale. These requests, displayed in Figure 5 below, were characterised by a high degree of mitigation and a combination of several politeness devices, which serve to convey a low degree of imposition and a high consideration for the interlocutor’s needs. It can be observed that each of these utterances was associated with ‘woman’ or ‘probably woman’ by 80% or above of the participants.6 Such a remarkably high degree of convergence in participants’ responses indicates the activation of shared stereotypical associations related to politeness and gender.

Figure 5.

Requests predominantly associated with female speakers based on linguistic stereotypes.

Rather than direct formulations, these utterances relied on interactional resources such as indirectness, vagueness, hedging, apologies, softeners, and hesitations, which reflect what has been described in the literature as a collaborative, non-imposing communication style, representative of Russian politeness norms. In this regard, participant 123 (W; 45–54; BA; Estonia; RNL; Russian, Estonian) states: “косвенные формулировки, как правило, воспринимаются как более вежливые и часто приписываются женской манере общения” (‘indirect formulations are generally perceived as more polite and are often attributed to women’s communication style’). This interpretation was supported by other participants’ responses, with the majority attributing these four requests to a female speaker, aligning with the dominant ideologies about gendered language use discussed in the literature (Zemskaya et al., 1993; M. H. Mills, 1999; Garanovich, 2020).

The first request was formulated through the imperative позвони (‘call’), but simultaneously mitigated by the politeness marker пожалуйста (‘please’), the conditional clauses если можно (‘if possible’) and если есть время (‘if you have time’), and the explicit justification for the request: у меня что-то телефон не очень хорошо (‘my phone is not working very well’) or у меня что-то со звонком. Я не могу понять (‘there is something wrong with the ringtone. I can’t understand’). Over 86% of participants identified the speaker as either ‘woman’ (32%) or ‘probably woman’ (54.4%).

The second request, expressed through an interrogative format, was softened by the modal predicate можно (‘can’), which frames the request as permission-seeking, and the use of the diminutive кусочек (‘little piece’). The percentage of respondents associating this request with a woman was even higher, 88.8%, with 44% choosing ‘woman’, 44.8% ‘probably woman’, and nobody opting for ‘man’. Participant 122 (W; 25–34; Estonia; BA; RNL; Russian, Estonian, English) commented that it was clear to her that such an indirect request was produced by a woman: “в этом примере для меня было очевидно, что говорит женщина. Вопрос у мужчины был бы прямой и четкий. ‘Можно мне сыра?” (‘In this example, it was obvious to me that it is a woman speaking. A man would have asked directly and clearly. “Can I have some cheese?”’).

The third request combined an apology извините (‘excuse me’), a negative interrogative construction а вы не…? (‘won’t you…?’), and the tag question да? (‘right?’), resulting in a tone that the majority of respondents (81.6%) linked to a woman (26.4%) or probably a woman (55.2%).

Prompt 4 was more complex: the speaker avoids expressing the actual request, offering instead a detailed contextual explanation and distributing fragmentary cues about the assistance required. This avoidance strategy, combined with the strong, conventionalised apology Вы извините ради бога (‘excuse me for the love of God’) and diminutives such as вопросик (‘little question’) and минутку (‘little minute’), led 80% of respondents to link it to a female (35.2%) or probably female (44.8%) speaker.

One of the respondents (P116; W; 18–24; BA; Estonia; RNL; Russian, Estonian, English) observed: “Женщины могут чаще добавлять смягчающие выражения, чтобы не звучать требовательно, тогда как мужчины могут использовать более прямые выражения” (‘Women may be more likely to add softening language to avoid sounding demanding, while men may use more direct language’). Interestingly, however, the same participant attributed all four requests to ‘man’ or ‘probably man’, more or less consciously contradicting both the dominant pattern and her own statement. This suggests that the participant was aware of dominant narratives and engaged with them at a discursive level when formulating metapragmatic reflection. At the same time, she had not fully internalised them and did not apply them to her own judgements. Alternatively, this could be a way of acknowledging the existence of gender stereotypes and expectations while consciously distancing herself from them in practice.

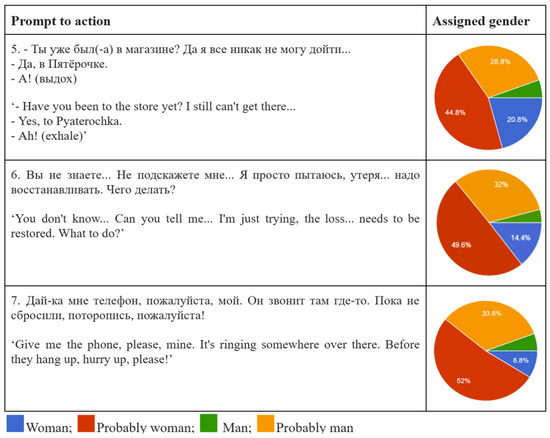

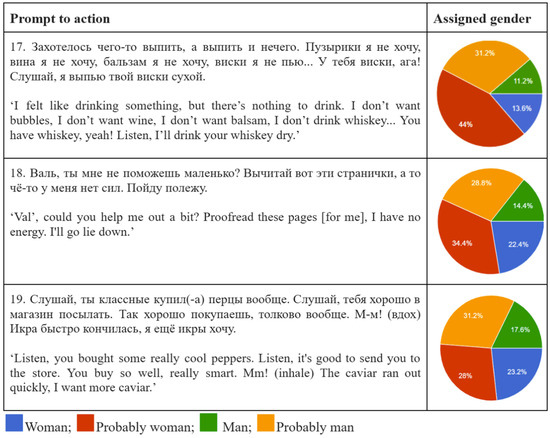

The second group included requests that exhibited some of the features previously discussed, such as indirectness, vagueness, mitigation, and hesitations. They were, however, less prominent, as these requests were more speaker-oriented than hearer-oriented. Moreover, these utterances were more pragmatically complex because of their ambiguous emotional tone or lack of clarity.7 This may explain why they were evaluated as slightly less polite overall, with average scores ranging from 2.5 to 3.4 on a 5-point scale. While the pattern was less consistent than in the first group, these requests tended to be predominantly attributed to women by around 60%–65% of respondents,8 as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Requests associated with female speakers based on linguistic stereotypes.

Prompt 5 was presented in the questionnaires as a недосказанная просьба (‘truncated request’), as the actual request remained unspoken. The question functioned as a pre-request to assess whether the conditions were right for asking a favour.9 From the addressee’s answer, the speaker infers that the request could not be fulfilled and therefore avoids formulating it. The use of an indirect pre-request can be regarded as either a face-saving strategy, as it prevents an explicit refusal, or an unmarked interactional resource signalling shared background knowledge. In either case, it performs supportive, relational work. Although quite a large proportion chose ‘probably man’ (28.8%), the majority of respondents linked this prompt to a female speaker, selecting ‘probably woman’ (44.8%) or ‘woman’ (20.8%). In this case, responses may have also been influenced by stereotypical associations that link grocery shopping and domestic tasks to women.

Prompts 6 and 7 were also pragmatically complex and ambiguous. The first contained a fragmented, hesitant utterance aimed at asking for assistance indirectly. Clearly, this verbal disfluency, marked by emotional, disorganised speech, incomplete syntax, repetitions, and filler words, tended to be associated with a woman (‘probably woman’ 49.6%; ‘woman’ 14.4%). This may indicate that the stereotype about women’s speech being more emotional, illogical, incoherent, and redundant, in contrast to the assertive and confident male speech behaviour (Garanovich, 2020, pp. 133–134), influenced participants’ guesses to some extent. Even when the tone was more impatient and the request more assertive, as in prompt 7, the use of repetitions (пожалуйста, ‘please’), of seemingly unnecessary linguistic items (-ка, где-то, ‘somewhere’) and explanations (он звонит там, ‘it is ringing over there’) led the majority of respondents to assign this request to a woman (‘probably woman’ 52%; ‘woman’ 8.8%). Nonetheless, the touch of assertiveness seemed to have introduced a degree of hesitation in participants’ choices, which were slightly less consistent compared to the first group of requests. Notably, the percentage of votes for ‘woman’ (8.8%) was the lowest among the requests analysed so far.

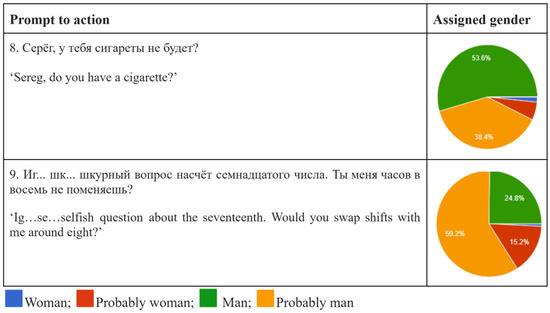

The third group comprised two particularly relevant requests that, despite being apparently similar to the ones previously analysed, were predominantly associated with a male speaker10 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Requests predominantly associated with male speakers based on specific lexical and stylistic choices.

On one hand, these requests were, similarly to prompts 1–7, indirect and non-imposing. They were formulated through negative interrogative constructions, conveyed consideration for the addressee, and contained hesitations. On the other hand, participants’ gender attributions in these cases diverged noticeably from the prompts previously examined. Participant 119 (W; 55–64; BA; Estonia; RNL; Russian, Ukrainian, Estonian, English), who assigned both these requests to a man, specifically commented on them in the following way: “Фразы короткие, лаконичные, функциональные, сосредоточенные на точной передаче информации и получении ответа на запрос” (‘The sentences are short, concise, functional, focused on conveying information accurately and getting an answer to the request’). This comment once again aligns with the stereotypes discussed earlier, framing male speech as more efficient, concise, and content-oriented (Garanovich, 2020, pp. 133–134). It can therefore be hypothesised that although these requests were indirect in form, they were regarded as more concise, particularly due to the absence of overt politeness markers, which are stereotypically less frequent in male speech (Garanovich, 2020, p. 147).

Moreover, the fact that the vast majority of participants (92% in 8; 84% in 9) associated these utterances with male speakers can be explained by the specific lexical and stylistic choices employed in the utterances. Participant 122 (W; 25–34; BA; Estonia; RNL; Russian, Estonian, English) reflected on prompt 8: “в этом примере для меня был очевиден ответ—говорит мужчина. Потому что женщина назвала бы полное имя или уменьшительно ласкательное. Очень четкий и прямой вопрос, женщина скорее всего что-то добавила бы. “Сереж, у тебя, случайно, не будет сигаретки?” (‘In this example, the answer was obvious to me—it is a man speaking. Because a woman would have used the full name or a diminutive affectionate one. It is a very clear and direct question. A woman would most likely have added something. “Serezha, do you have a cigarette by any chance?”’). Apart from the distinction between concise and verbose requests discussed above, this reflection highlights how forms of address, diminutives, and filler words were used as indicators of the speaker’s gender. For instance, the use of the colloquial Серег (Sereg) instead of the more standard and affectionate Сереж (Serezh) was perceived as a gendered linguistic choice, reflecting the stereotype that men tend to use less emotionally expressive and more non-standard language (Garanovich, 2020, p. 146). Similarly, the use of the colloquial, low-register adjective шкурный (‘selfish’) in prompt 9 likely reinforced the perception of the speakers as male. Furthermore, participants’ guesses may also have been influenced by broader social associations, for instance, linking smoking with men (8) or viewing men as more comfortable describing their own behaviour as selfish (9).

The fourth group included three requests that were more consistently associated with male speakers11 and undoubtedly not as a result of linguistic stereotypes alone. More predominantly than in the previously analysed instances, gender attributions in this group of requests appear to have been influenced by contextually and socio-culturally biased associations.

As shown in Figure 8, it was not only request 10, which is assertive, brief, and direct, that was attributed to a man (17.6%) or probably a man (54.4%). Prompt 11, despite containing repetitions (e.g., the politeness marker пожалуйста, ‘please’, as in request 7), hesitations (э-э, ‘ehm’; и…, ‘and…’), fillers, and discourse markers (потому что вот, ну ‘because well’), was ascribed to ‘man’ (10.4%) and ‘probably man’ (55.2%) by the majority of respondents (65.6%).

Figure 8.

Requests associated with male speakers based on linguistic and social stereotypes.

Remarkably, the percentage of attributions to a male speaker was even higher (80.8%) for prompt 12, which is syntactically complex and verbose, marked by vagueness (кого-нибудь, ‘someone’; некое, ‘a certain’), use of discourse markers (как бы, ‘kinda’), and hesitations (э-э, ‘ehm’; нако…накопилось ‘accu…accumulated’). Moreover, although the request was overall evaluated as impolite, with an average politeness rate of 1.4 in both questionnaires, it is not explicitly direct or imposing. It is expressed through a speaker-oriented modal construction (мне нужно будет постирать, ‘I will need to wash’) accompanied by conditionals (Не хочешь стирать, не надо, ‘if you don’t want to wash, don’t; если тебе тяжело и не хочешь, ‘if it’s hard for you and you don’t want’), which make it more negotiation-oriented than content-oriented. Following the patterns observed in previous cases, such linguistic features could be expected to elicit more balanced gender attributions, yet this request received the second-highest percentage of male attributions in the dataset (following prompt 8), with 80.8% of respondents selecting ‘man’ (46.4%) or ‘probably man’ (34.4%). This suggests that other factors, particularly stereotypes linked to traditional gender roles and societal expectations, may have played a crucial role in participants’ guesses. This idea is reflected in the comment by participant 31 (M; 25–34; MA; Finland; RNL; Russian, English, Finnish), who emphasised the crucial influence of socio-cultural associations and sexism:

“Мне кажется, что многие фразы могут с легкостью принадлежать как мужчинам, так и женщинам. Также очень сильно на ответ может повлиять не сама фраза, а ‘сексизм’. Например, неосознанное отношение, что мужчина начальник, а женщина подчиненный, что мужчина уходит на работу, а женщина остается дома. А ведь все может быть с точностью до наоборот. Сами просьбы нейтральные, если не задумываться о том, кто бы мог их произнести” (‘It seems to me that many sentences can easily belong to both men and women. Also, the answer can be strongly influenced not by the sentence itself, but by “sexism”. For example, an unconscious attitude that a man is a boss and a woman is a subordinate, that a man goes to work and a woman stays at home. But everything can be exactly the opposite. The requests themselves are neutral, if you do not think about who might have said them’).

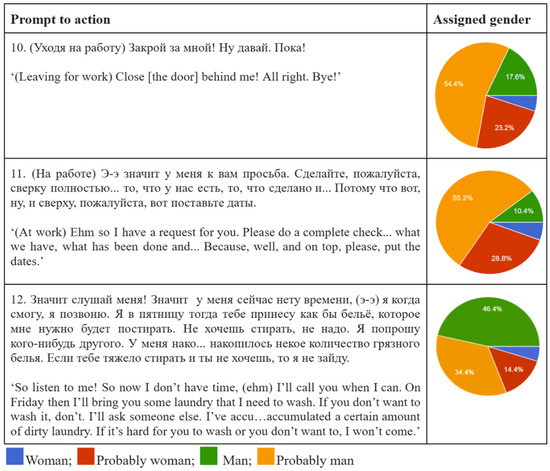

Therefore, responses were, whether consciously or unconsciously, guided by an interplay of linguistic and socio-cultural stereotypes, with the latter having an even more salient impact on how participants inferred the speaker’s gender. The reference to the laundry in prompt 12, which was not explicitly mentioned by participant 31, may have also activated traditional gender stereotypes associating women with taking care of domestic responsibilities and men delegating them. This interpretation was further reinforced by the attribution of the following four requests predominantly to female voices, as illustrated in Figure 9. This group included four requests that, similarly to those just discussed, may have been interpreted primarily through stereotypical socio-cultural associations rather than linguistic choices alone.12

Figure 9.

Requests associated with female speakers based on social stereotypes.

Prompts 13 and 14, for instance, involved references to domestic and childcare responsibilities, namely clearing the table and urging a child to do their homework. The fact that in spite of the use of a blunt and impolite expression like какого ты хрена (‘why the hell’), stereotypically attributed to men (Zemskaya et al., 1993; Garanovich, 2020), prompt 14 was still predominantly related to a woman (29.6%) or probably a woman (33.6%) points to the probable influence of ideologies related to traditional family roles. Prompt 15 similarly featured a direct, task-oriented request, introduced by an irritated question and followed by an explicit, albeit softened, imperative. However, the preconception that it is typically women who are concerned and complain13 about disorder and noise at home, like a loud television, appears to have been relevant.

Participants’ responses were less consistent in prompt 16, since, as noted by participant 120 (M; 25–34; BA; Estonia; RNL; Russian, Estonian), here linguistic and social stereotypes collided: “Одним из самых интересных примеров была фраза: «Сфоткай меня, бл*дь!». На первый взгляд, она кажется грубой и, следовательно, мужской. Однако после размышлений я пришёл к выводу, что фотографироваться чаще любят женщины, и вполне возможно, что они могут использовать такую лексику” (‘One of the most interesting examples was the sentence: “Take a picture of me, f*ck!” At first glance, it seems rude and, therefore, masculine. However, upon reflection, I came to the conclusion that women like to take pictures of themselves more often, and it is quite possible that they can use such vocabulary’). Likewise, albeit more implicitly, participant 43 (W; 35–44; PhD; Germany; RNL; Russian, English, German) stated: “Сложно сказать :) про телевизор потише и про сфоткай сверху—уверена что женщина—остальные могут дать и то и то”, ‘Hard to say :) about turn down the TV and take the photo from above—I’m sure it’s a woman—the others could be both’, indicating that two of her guesses were informed by socio-cultural associations, while the other prompts were not perceived as gendered.

Finally, the remaining requests, in which a more balanced distribution across gender categories was observed, are represented in Figure 1014:

Figure 10.

Participants’ responses more evenly distributed across gender categories.

In these cases, there was no dominant pattern in participants’ responses, suggesting that prompts 17–19 did not activate strong stereotypical assumptions shared by most participants. However, qualitative data revealed that such a balanced distribution did not necessarily reflect a gender-neutral perception, but in some cases, it may have indicated the coexistence of multiple associations. For instance, participant 115 (W; 45–54; BA; Estonia; RNL; Russian) disclosed that her uncertainty about the gender of the speaker in prompt 17 was not related to its neutrality, but to the lack of contextual information and the ambiguity of the word пузырики (lit, ‘little bubbles’), which may either refer to champagne, which she interpreted as a feminine drink, or to some stronger, ‘manly’ sparkling cocktails. Thus, her choices seem to be guided by gendered drink preferences:

“Слово ‘пузырики’ вызывает ассоциацию с шампанским, т. е. женским напитком, что наталкивает на мысль, что фраза принадлежит женщине. Однако, сейчас есть много коктейлей с крепким алкоголем с ‘пузырьками’, которые употребляют и мужчины. Что говорит о том, что это выражение может в равной степени исходить как от женщины, так и от мужчины. Я пришла к выводу, что очень много зависит от контекста, который оказался скрыт от нас” (‘The word ‘bubbles’ evokes an association with champagne, i.e., a woman’s drink, which suggests that the sentence belongs to a woman. However, there are now many cocktails with strong alcohol with “bubbles” that are consumed by men too. Which suggests that this expression can equally come from a woman or a man. I came to the conclusion that a lot depends on the context, which was hidden from us’).

Similar contradictions were also identified when comparing comments given by different respondents. On the one hand, participant 19 (W; 25–34; MA; Estonia; RNL; Russian, Estonian, English), choosing ‘probably woman’ in prompt 17, commented: “Относительно гендера я руководствовалась стереотипами, напр. диминутивы (пузырики) используются женщинами. Однако в наше время, мне кажется, практически невозможно определеть [sic] гендер говорящего по его высказыванию” (‘Regarding gender, I was guided by stereotypes, for example, diminutives (little bubbles) are used by women. However, in our time, it seems to me almost impossible to determine the gender of a speaker from their utterance’). On the other hand, participant 124 (M; 35–44; BA; Estonia; RNL; Russian, Estonian), without making his thought process explicit, but implying that prompt 17 brought some clear associations to his mind, selected ‘probably man’: “Конечно, в некоторых из приведённых примеров можно было угадать пол говорящего (например, в примере про виски и пузырьки), но не на все сто процентов” (‘Of course, in some of the given examples it was possible to guess the gender of the speaker (for example, in the example about whiskey and bubbles), but not with complete certainty’).

These comments also highlight an even more relevant contradiction, which is not exclusive to these responses and will be discussed in Section 6: respondents frequently recognised the inadequacy of gender ideologies and stereotypes while still, at least partially, relying on them.

5.2. Participants’ Evaluations of Politeness

Having confirmed the existing preconceptions about the link between gender and the linguistic expression of politeness in request formulation, evident in many participants’ responses to both close and open-ended questions, this subsection examines whether and to what extent these stereotypes influenced participants’ perception of politeness.

Specifically, this section analyses participants’ responses to the 5-point Likert-scale questions in Q1 and Q2 from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives. As explained in detail in Section 4, participants had to evaluate the degree of politeness of each prompt on a scale ranging from 1 (‘impolite’) to 5 (‘very polite’). In Q1, for each prompt, participants had to first imagine and indicate the presumed gender of the speaker and only afterwards rate its politeness, whereas in Q2, only politeness ratings were collected, with no mention of gender.

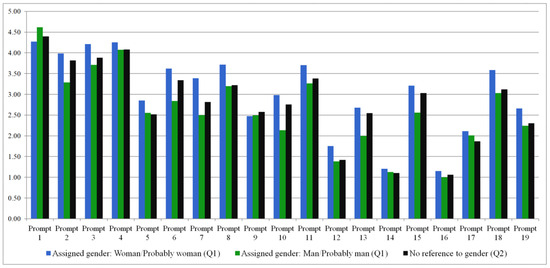

The results are summarised in Figure 11. The prompts appear in the same order as in Section 5.1. Average politeness ratings were calculated for each of them, distinguishing between cases where the speaker was identified as ‘woman’ or ‘probably woman’ (blue columns) and those where the speaker was identified as ‘man’ or ‘probably man’ (green columns). These values are presented alongside the corresponding scores in Q2 (black columns) for comparison.

Figure 11.

Average politeness ratings in participants’ responses.

A clear trend emerges from the data: with the sole exceptions of prompts 1 and 9, identical utterances received higher politeness ratings when participants imagined a woman producing them. Interestingly, in all 17 cases, these ratings were not only higher than those assigned when the same utterances were associated with a male speaker, but also exceeded those given in the gender-neutral condition (Q2). This pattern holds even in cases where low-register or obscene language was explicitly used, as in prompts 12, 14, and 16. The lowest politeness ratings were registered when utterances were attributed to male speakers in 15 out of 19 cases.

The difference between female- and male-attributed ratings exceeded 0.5 in more than half of the requests (9 out of 19), with the most significant differences found in prompts 6 (+0.78), 7 (+0.89), and 10 (+0.85). This consistent pattern reflects what in cognitive social psychology has been described as the assimilative effect of gender stereotypes (cf. Biernat & Sesko, 2018), meaning that participants subconsciously interpreted speech data in a way that aligns with pre-existing expectations. In other words, these results demonstrate that the perceived speaker gender had a strong influence on politeness judgements, likely due to the preconception that women are generally more polite than men in interaction.

It is, however, relevant to mention that the comparisons of politeness ratings for some requests should be interpreted with caution, acknowledging potential limitations. As highlighted in the previous subsection, several prompts exhibited a pronounced imbalance in gender attributions. For instance, prompt 1 was attributed to male speakers by only 17 participants (13.6%), resulting in a disparity that can compromise the statistical reliability of the average politeness ratings for the underrepresented group. The same applies to all the other prompts that share similar asymmetries.

A further consideration about the data presented in Figure 11 concerns the composition of the two separate participant groups for Q1 and Q2. As shown in Section 4.2, although both questionnaires were distributed within similar online communities, the resulting samples differed notably in their geographic composition, with 40.8% of Q1 respondents living in Estonia compared to only 10.3% in Q2, and 23.2% of Q1 participants based in Russia compared to 46.8% of Q2 (cf. Figure 3). Given that regional and cultural backgrounds can shape individuals’ expectations and ideas about politeness and gender, the differences observed between the two groups may reflect culturally informed perceptions rather than the effect of the gender attribution task alone. To address this, future studies on (im)politeness perception in Russian using a similar experimental design could benefit from matching participant groups more closely in terms of regional background or investigating more specifically the role of geographical variation in shaping politeness evaluation.

6. Discussion

The results confirmed that in Russian, specific linguistic choices tend to be stereotypically associated with a particular gender and that these associations can influence individuals’ perception of (im)politeness. Nonetheless, these findings should be treated as tendencies rather than absolute patterns and must be contextualised by taking into consideration what participants indicated as guiding their inferences. Although only 70% of respondents answered the open-ended question at the end of Q1, and in some cases it was not clear whether they were reasoning on gender specifically or on politeness norms in broader terms,15 these responses provide valuable insights.

Respondents made explicit reference to the following criteria, often in combination: contextual and real-life associations (8%), personal experience (10%), personal opinion and knowledge (2%), linguistic cues (23%), stereotypes (8%), intuition (10%), and emotional reactions or impressions when imagining the dialogue (9%).

In light of the findings presented in Section 5.2, it cannot be excluded that the real-life associations and personal experiences on which some participants based their judgements16 were, at least in part, distorted by attention and memory biases (Biernat & Sesko, 2018). However, it is equally plausible that these associations reflected actual communicative situations and gendered patterns they had observed in their life. This highlights the deep interconnection between real-life linguistic experience and stereotypical expectations, which is evident from comments such as: “Стереотипы, основанные на личном опыте” (‘[I relied on] stereotypes based on personal experience’; P69; W; MA; 25–34; Russia; RNL). Far from being a contradictory statement, this suggests that stereotypes not only shape everyday interaction but are themselves shaped by it. As discussed in Section 2, gender ideologies and stereotypes are not abstract ideas passively internalised and operating solely on a cognitive level. Rather, they are socially produced and reproduced as language users belonging to different social groups, often unconsciously, conform to them and reinforce them (Doise, 1978). This dynamic explains the apparent contradictions found in many comments, such as the ones discussed in Section 5.1, in which participants simultaneously rejected and relied on gender stereotypes. This was particularly evident in the reflection by participant 14 (W; 35–44; MA; Estonia; RNL):

“Если честно, в большинстве случаев мне легко представить и женщин, и мужчин, и если бы была опция, я бы почти везде выбрала, что пол не важен. Сейчас везде выбрала женщин, потому что по моему опыту, женщины вежливее мужчин в среднем. Так же мне кажется, что женщины чаще используют диминутивы, но возможно это только кажется. Ещё мне кажется, что женщины меньше используют именно мат и менее агрессивны” (‘To be honest, in most cases it is easy for me to imagine both women and men, and if there had been such an option, I would have almost always chosen that gender is not important. Now I have chosen women everywhere, because in my experience, women are more polite than men on average. It also seems to me that women use diminutives more often, but perhaps it just seems that way. It also seems to me that women use less obscene language and are less aggressive’).

On the one hand, she questions the relevance of gender in interpreting the utterances, although the inclusion of the adverb почти (‘almost’) already makes her claim less categorical.17 On the other hand, she notes that certain patterns emerged from her personal experience and were used as a basis for her inferences. The repeated use of hedges such as мне кажется (‘it seems to me’) and возможно (‘perhaps’), however, frames this observation more as a subjective impression, which highlights the blurred boundary between personal experience and internalised expectations. This demonstrates how stereotypes and expectations influence both language production in everyday interaction and language perception, even in cases of high metapragmatic awareness.

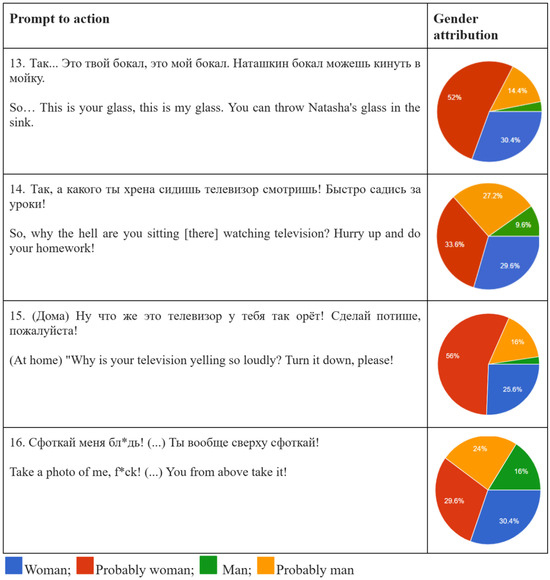

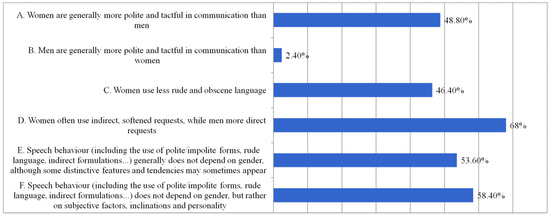

Ambivalence can be observed in responses to the final multiple-choice question, which asked participants to select the statement(s) they agreed with regarding gender and speech behaviour. As shown in Figure 12, while more than half selected option F, which explicitly rejected the idea that speech behaviour depends on gender, many also simultaneously selected A, C, and/or D. Notably, only 2.4% of respondents (n = 3) agreed with the statement that men are generally more polite than women, confirming the clear asymmetry in how politeness is perceived through the lens of gender ideologies.

Figure 12.

Responses to the final multiple-choice question.

It should be noted that only nine participants selected option F exclusively. All were women belonging to different age groups (18–64) living in Italy (n = 3), Estonia, Ukraine, Latvia, Russia, the Czech Republic, and Turkey. Similarly, answer E alone was chosen by nine participants,18 while six others selected both E and F.19 Interestingly, only one participant who selected F explicitly rejected any link between gender and linguistic behaviour: “Почти во всех случаях, где нужно было определить гендерную принадлежность говорящего, если был ответ ‘понятия не имею’, я бы выбирала его. Поэтому руководствовалась тем, что нужно выбрать кружочек” (‘In almost all cases where I had to identify the speaker’s gender, if there was an “I don’t know” option, I would have chosen it. So I just picked a circle because I had to’; P56; W; 45–54; BA; Ukraine; RNL). In contrast, participant 113 (W; 35–44; BA; Estonia; RNL) expressed the idea of a natural connection between gender and politeness: “Я думаю, что гендер и вежливость взаимосвязаны. Женщины более вежливы по природе, они более стеснительные и не любят конфликты, и ведут себя более воспитанно, чем мужчины. При определении гендерной принадлежности говорящего их фразы были заметны” (‘I believe that gender and politeness are interrelated. Women are more polite by nature, they are more shy, avoid conflict and behave more appropriately than men. When identifying the speaker’s gender, their utterances were clearly recognisable’). These two responses, representing the most polarised positions in the dataset, illustrate the diversity of beliefs among participants, which makes it difficult to make broad generalisations about their responses. Nonetheless, participants’ responses provided further evidence for the role of stereotypes in shaping ideas about the relationship between gender and (im)politeness in Russian, as well as the perception of politeness itself. Although many comments suggest an attempt to distance themselves from such stereotypes, participants also appeared to acknowledge the social and pragmatic nuances of real-life communication in Russian-speaking contexts, where dominant gender ideologies, expectations, and socially constructed norms continue to play a significant role.

While these findings mark a significant contribution to the study of linguistic gender stereotypes and their effect on politeness perception in Russian, some study limitations, beyond those outlined in Section 5.2, should be acknowledged. The first limitation pertains to the presentation of linguistic stimuli in the questionnaires. Participants were asked to evaluate decontextualised utterances, with only limited information provided about the interactional context. This format was intentionally chosen to enhance the ecological validity of the experiment by allowing respondents to imagine realistic scenarios and interpret them based on their own communicative experience, rather than imposed contextual frames. Nonetheless, the absence of contextual details may have led them to fall back on stereotypes and biased associations, rather than engaging in context-sensitive pragmatic reasoning.

The second limitation concerns the composition of the participant pool. First of all, the sample was not fully balanced in terms of gender, as it included relatively few male respondents. As a result, the findings are only partially representative of the broader population of Russian speakers and may primarily reflect the perspective of female respondents. In addition, even though the overall tendencies in gender attribution and politeness perception remained consistent across groups, the inclusion of participants with diverse linguistic profiles, ranging from RNL to RFL speakers and from monolingual to multilingual users, may have introduced potential variability in how politeness norms were interpreted and evaluated. Given that pragmatic awareness is shaped by a wide range of social, cultural, and regional factors, and above all by individual linguistic experience, politeness judgements may have been informed by metapragmatic beliefs and norms associated with other languages actively used by the participants. This is particularly relevant when data from RNL and RFL speakers were combined, as variability in pragmatic competence and in sensitivity to contextually appropriate language use can raise methodological challenges, complicating the comparability of judgements across the sample and the interpretation of the results. Future empirical research should explore in greater depth, with larger and more balanced samples, how speakers’ sociolinguistic profiles can relate to linguistic gender stereotypes and the perception of (im)politeness in Russian.

7. Conclusions

This study set out to explore, in a sample of 251 Russian-speaking respondents, stereotypes and preconceptions about gendered politeness norms, with a particular focus on Russian requests and prompts to action. In addition, it aimed to investigate whether such stereotypes, for instance, the belief that women are generally more polite than men, tended to affect participants’ evaluations of (im)politeness. Specifically, the experiment tested if the same utterance was judged as more or less polite depending on whether it was associated with a man or a woman (Q1) or when no assumptions about the speaker’s gender were prompted (Q2).

By investigating the relationship between linguistic gender stereotypes and (im)politeness perception from an empirical perspective, this study makes a significant contribution to an underexplored area in the field of Russian gender linguistics at the intersection of sociolinguistics and pragmatics.

The findings confirmed both hypotheses outlined in the introduction. First, the analysis showed that specific lexical, syntactic, and stylistic choices in Russian tend to be associated with a particular gender. Both qualitative and quantitative data indicated that when making their guesses about speakers’ gender, most respondents strongly relied on linguistic gender stereotypes, particularly the preconception that women are more polite than men and tend to prefer indirect and more elaborated formulations when expressing a request or a prompt to action. Indirect request formulations that combined mitigation forms and strategies aimed at reducing imposition and performing relational work, such as polite formulas, conditional clauses, modal constructions, diminutives, apologies and justifications, were consistently attributed to women. Similarly, utterances that displayed emotional, disorganised speech filled with vagueness, hedging, hesitations, and repetitions tended to be associated with female speakers. This tendency was particularly evident in prompts 1–4, where over 80% of participants selected either ‘woman’ or ’probably woman’. Conversely, more direct, concise, or assertive formulations tended to be associated with men, especially if containing low-register, colloquial, or obscene language. Gender attributions in prompts 8, 9, and 10 clearly illustrated this tendency.

However, the analysis also revealed that participants’ judgements were not guided solely by linguistic features. In several cases, social stereotypes concerning traditional gender roles appeared to play an even more crucial role in informing participants’ guesses. One of the most illustrative examples was prompt 12, which—despite being linguistically complex, vague, disorganised, and in fact originally produced by a female speaker—was predominantly attributed to a man. This suggests that participants were influenced not by the linguistic formulation, but rather by the stereotype that men are more likely to delegate household tasks such as doing the laundry. Similarly, prompts containing linguistic features elsewhere associated with male speakers tended to be assigned to women when the context involved domestic or caregiving activities.

The second hypothesis was also supported. The analysis revealed that in Russian, the social construction of politeness as a feminine trait influences its perception, as confirmed by the comparison of participants’ average politeness ratings for each of the 19 prompts. In 17 cases, the same request received higher politeness ratings when participants imagined it being said by a woman compared both to when it was attributed to a man (Q1) and when the parameter of gender was excluded (Q2). In the context of this study, this tendency can be interpreted in light of what Biernat and Sesko (2018) describe as the assimilative influence of gender stereotypes, whereby linguistic perception is filtered through individuals’ expectations. In other words, the higher politeness ratings associated with female speakers suggest that women were not simply believed to be, but also more readily perceived as more polite.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for this study in accordance with the Procedure of the Tallinn University Ethics Committee (Order No. 10 of 14 January 2020; amended by Order No. 118 of 4 November 2021), as the research does not fall under the categories requiring approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Kapitolina Fedorova for the valuable support in designing the experiment and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For more detailed information on the two corpora, see Asinovsky et al. (2009) and Kitaygorodskaya and Rozanova (1999). |

| 2 | A subset of respondents (participants 112–124), all Russian–Estonian bilinguals and native speakers of Russian (with one exception), were asked to provide more detailed reflections on their choices, including comments on specific prompts they found particularly interesting, as well as on the perceived relationship between politeness and gender. |

| 3 | It is important to mention that defining “native language” may be problematic, especially in multilingual contexts, as early language acquisition is neither the sole nor necessarily the most relevant criterion (Skutnabb-Kangas, 1981). The label may reflect identity positioning or cultural affiliation rather than actual competence or patterns of language use. Contemporary sociolinguistic research has increasingly questioned the validity of a rigid native/non-native speaker dichotomy, proposing instead a view of language proficiency as a continuum shaped by communicative practices. |

| 4 | In the majority of cases, Russian was spoken alongside other languages in everyday life, with a small percentage referring to speaking exclusively Russian on a daily basis. This was the case for 16% of respondents in Q1 (n = 20; 14 living in Russia, 3 in Estonia, 1 in Latvia, 1 in Kazakhstan and 1 in Uzbekistan) and for 24.6% of respondents in Q2 (n = 31; 26 living in Russia, 2 in Kazakhstan, 2 in Belarus and 1 in Estonia). Russian was not included among the languages spoken daily by seven participants in Q1 (six living in Italy and one in Poland) and five in Q2 (three living in Italy, one in Kazakhstan, and one in Croatia). |

| 5 | As Fedorova and Tshuikina (2024) observe, despite being officially a monolingual country, Estonia has a rich and diverse linguistic landscape and soundscape, particularly in urban areas like Tallinn. This is reflected in data from Q1, where participants from Estonia were the majority (n = 51). With the exception of three monolinguals, Russian, English, and Estonian are actively used on a daily basis. In addition to the ‘big three’, many other languages were reported as being used daily. The following clusters were registered: Russian, Estonian, and English (n = 19); Russian and Estonian (n = 15); Russian, English, Estonian in combination with one or more additional languages, including Ukrainian, Italian, Finnish, Georgian, Spanish, Japanese, and Romanian (n = 9); Russian and English (n = 1); Russian, English, and Ukrainian (n = 1) or Romanian (n = 2); Russian, Estonian, and Ukrainian (n = 1). |

| 6 | These four requests were uttered by women in the original materials. |

| 7 | This is explicitly mentioned in a comment in Q2, in which a male participant from Kazakhstan (P157; 35–44; BA; RNL; Spanish, English and Kazakh) compares the third request with the fifth in the following manner: “Вопрос не прямой, а с намеком: “вы не разогреваете?” - еще больше смягчает обращение. Хотя в примере с пятерочкой даже трудно уловить просьбу, поэтому такое обращение наоборот просьбу менее вежливой” (‘If the question is not direct, but with a hint: “could you warm it up?” [3], it softens the request even more, though in the example with the Pyaterochka [5], it is difficult even to catch the request, and therefore such an address on the contrary makes the request less polite’). |

| 8 | Requests 5 and 7 were originally pronounced by women, and 6 by a man. |

| 9 | On Russian pre-requests, see Rudneva (2019). |