2.1. Singulatives

Singulatives occur robustly in East Slavic languages but. to various degrees, are attested in all branches of North Slavic (e.g.,

Asmus & Werner, 2015;

Corbett, 2000;

Geist et al., 2023;

Ivanović, 2020;

Kagan, 2024;

Kagan & Nurmio, 2024;

Wągiel & Shlikhutka, 2023a,

2023b;

Wierzbicka, 1988). In Slavic, similar to, e.g., Celtic, Arabic and Nilo-Saharan languages such as Luo (

Dali & Mathieu, 2021), singulative morphology is used to turn uncountable nouns into countable ones. One of the Slavic derivational morphemes standardly analyzed as a singulative affix is the suffix

-in, which in different Slavic languages and/or different phonological environments takes the form

-in,

-yn or

-en.

Table 1 gives an overview of the North Slavic singulative formation. In South Slavic, the discussed type of singulativization is either entirely marginal or non-existent.

2The suffix

-in attaches to uncountable aggregate bases, whose referents are typically conceptualized as clustered collections of unindividuated entities, and forms countable unit nouns, which designate singular individuated objects. To illustrate, let us consider a couple of examples in

Table 1. For instance, the Belarusian noun

saloma ‘straw’ is an uncountable aggregate noun that is typically used to refer to clustered dried plant stalks. In contrast, the singulative form

salomina ‘a straw’ is a countable singular unit noun that designates a single straw (

Lukašanec, 2016). Similarly, the Ukrainian noun

pisok ‘sand’ typically denotes an aggregate of sand, whereas the singulative

piščyna ‘a grain of sand’ is true of singular grains. Finally, the Upper Sorbian noun

sněh translates as ‘snow’ and

sněženka is the equivalent of ‘snowflake’ (

Asmus & Werner, 2015).

Despite the fact that the singulative formation is (to various extents) attested in all languages in question, there is a stark difference in the occurrence of the category in East and West Slavic. While singulatives are widespread in East Slavic, there are only a few remnants in West Slavic, with the Polish form

śnieżynka ‘snowflake’ being probably one of the only three preserved in the language.

3It is also important to emphasize that

-in is a multifunctional element that is used to derive various kinds of nouns. Though its functions differ across Slavic, some frequent uses concern, e.g., formation of spatial collectives designating names of forests, as in (7) (e.g.,

Wągiel, 2021a), and diminutivization expressing appreciation (or sometimes pity), seen in (8). For the most part, in this paper, I will only consider the proper singulative function illustrated in (5) and

Table 1. However, in

Section 3, I will examine morphological evidence from Czech hypocoristics and diminutive adjectives derived with

-in.

| (7) | grab ∼ grab-in-a |

| | hornbeam.sg hornbeam-in-sg |

| | ‘a hornbeam’ ∼ ‘a hornbeam grove’ | (Polish, Wągiel, 2021a, p. 185) |

| (8) | chłop ∼ chłop-in-a |

| | guy.sg ∼ guy-in-sg |

| | ‘a guy’ ∼ ‘a good-natured guy’ | (Polish) |

Though exploring all functions of

-in and their relationship is beyond the scope of this paper, it should be emphasized that there are attempts in the literature to capture this multifunctionality. For instance,

Kagan (

2024) proposes a unified analysis of the relationship between two different functions of

-in in Russian, namely, the singulative use in (5) and the massifier use in (9), which is based on the idea that the marker denotes an unspecified partition shifter.

| (9) | kon’ ∼ kon-in-a |

| | horse.sg horse-in-sg |

| | ‘horse’ ∼ ‘horsemeat’ | (Russian, Kagan, 2024, p. 37) |

Having discussed this paper’s main empirical focus in the nominal domain, let us now move to the verbal domain.

2.2. Semelfactives

Semelfactives are a very frequent verbal category attested in all branches of Slavic (e.g.,

Armoškaitė & Sherkina-Lieber, 2008;

Arsenijević, 2006;

Biskup, 2023a,

2023b;

Kagan, 2008;

Kwapiszewski, 2020,

2022;

Łazorczyk, 2010;

Markman, 2008;

Matushansky, 2024;

Milosavljević, 2023;

Nesset, 2013;

Nordrum, 2020;

C. Smith, 1991;

Štarkl et al., 2025;

Taraldsen Medová & Wiland, 2019;

Wiland, 2019). Slavic semelfactive morphology was argued to mark a number in the verbal domain and express eventive singularity and, thus, contrasts with event internal iteratives marked with the theme vowel

-a (

Armoškaitė & Sherkina-Lieber, 2008; see also

Milosavljević, 2023).

4 The suffix

-nu, which is responsible for semelfactive formation, in different Slavic languages and/or phonological contexts can take the shape

-nu,

-nou,

-ną,

-ni, etc.

Table 2 provides an overview of the iterative/semelfactive distinction across all branches of Slavic. Though there are important differences between individual Slavic languages,

5 in this paper, I will ignore them and focus on overall similarities.

The suffix

-nu attaches to bases that can be viewed as describing events that typically occur in series. For this reason, I assume that the bases such as those in

Table 2 are inherently iterative, i.e., denote eventualities that are conceptualized as allowing for multiple (quick) repetitions and are often experienced this way. The result of the

-nu suffixation is a punctual verb designating a very brief event that constitutes an instantaneous action, which at its endpoint returns to the initial state. For instance, the Ukrainian verb

stukaty ‘to knock (repeatedly)’ does not describe a singular knocking event, but rather a plurality thereof. In contrast, the derived semelfactive form

stuknuty ‘to knock once’ would be true of a single knock. Likewise, Bosnian/Croatian/Montenegrin/Serbian (BCMS)

lupati ‘to slap (repeatedly)’ and Slovenian

mahati ‘to wave (repeatedly)’ are iterative verbs denoting multiple occurrences of an action (typically in a series), whereas their semelfactive equivalents

lupnuti, ‘to slap once’, and

mahniti, ‘to wave once’, designate a singular slapping and waving event, respectively.

Across Slavic languages, semelfactive

nu-verbs can be either accusative or unergative and their stems involve roots that also derive nominals (

Taraldsen Medová & Wiland, 2019). This is illustrated by the Polish examples in (10), where

kop ‘kick’ and

syk ‘hiss’ are both attested nouns in the language.

| (10) | a. | Jacek kop-ną-ł | piłkę. | |

| | | Jacek kicked-smlf-pst ball.acc | |

| | | ‘Jacek kicked the ball.’ | |

| | b. | Jacek syk-ną-ł. | |

| | | Jacek hiss-smlf-pst |

| | | ‘Jacek hissed.’ | | (Polish, Taraldsen Medová & Wiland, 2019) |

Notice that, similar to

-in,

-nu also does not derive exclusively semelfactives but also other types of verbs. Its other functions across Slavic that should be mentioned include, e.g., imperfective degree achievement derivation, illustrated in (11), and plain activity formation, as in (12) (

Taraldsen Medová & Wiland, 2019;

Wiland, 2019). There are important lessons that can be learnt from examining similarities and differences between semelfactives and verbs such as those in (11)–(12), e.g., stems of

nu-degree achievements are always unaccusative and have adjectival roots (

Taraldsen Medová & Wiland, 2019).

Again, in this paper, I do not intend to investigate all uses of

-nu and how they relate; however, there are proposals attempting to account for the multifunctionality in question. For instance,

Taraldsen Medová & Wiland (

2019) argue that there is a containment relationship between semelfactives and degree achievements such as (11), namely, that the former contain the latter. Nevertheless, due to a limited scope, this paper concerns only bona fide semelfactives depicted in (6) and

Table 2.

Having discussed the basic characteristics of singulative nouns with -in and semelfactive verbs with -nu, let us now investigate some more interesting properties. In what follows, I will focus on data highlighting the analogies between the two categories in question.

2.3. Parallels

Mehlig (

1994) suggested that on a conceptual level, semelfactives are, in principle, the verbal counterpart of the category of singulatives. The goal of this section is to examine to what extent the idea concerning the analogy between semelfactives and singulatives goes beyond conceptual considerations and is supported by grammatical parallelism. Specifically, I will discuss five analogies between Slavic singulatives and semelfactives that regard their syntactic and semantic properties.

The first analogy concerns a non-trivial constraint on the formation of singulatives and semelfactives.

6 Recent research revealed that in Slavic, singulativization via

-in turns out to be restricted to a subset of uncountable nouns (

Geist et al., 2023;

Kagan, 2024;

Kagan & Nurmio, 2024;

Wągiel & Shlikhutka, 2023a,

2023b; see also

Grimm, 2012,

2018). As already stated in

Section 2.1,

-in only attaches to bases that convey an aggregate semantics, i.e., describe entities that typically occur in collections whose constituents are either spatially connected to each other or remain in close and predictable proximity. As such, they are conceptualized as clusters, i.e., spatially structured pluralities of objects. Some representative examples are given in

Table 3, which provides an overview of singulative bases in Ukrainian.

Ukrainian and other East Slavic languages form singulatives for many uncountable granular nouns with multiple examples of cereals, e.g.,

žyto ‘rye’ is the base for

žytyna ‘a grain of rye’, but also sand, sugar, beads, pearls, etc. Another class of frequent bases for the singulative formation with

-in involves object mass nouns describing artifacts that typically occur or are stored in heaps and piles, e.g.,

posud ‘dishes (as a mass)’ is an uncountable noun that serves as a base for its singulative counterpart

posudyna ‘a dish’, which denotes a singular discrete object. Similarly, many names of vegetables that are grown or stored in collections and bunches are object mass nouns in Ukrainian, e.g.,

morkva ‘carrot (as a mass)’ can be used to describe any amount of carrots in any form (both individuated as discrete entities and conceptualized as a mass), whereas

morkvyna ‘a carrot’ is true of a single item of the vegetable.

7 Finally, mass nouns designating precipitation can also form singulatives, e.g.,

rosa ‘dew’ and the derived form

rosyna ‘a dew drop’. Also, in this case, the base refers to a collection of drops, flakes, stones, etc., and not a homogeneous body of a substance. Thus,

-in always attaches to an aggregate base, which typically designates clustered objects, and forms a countable concrete unit noun that refers to a discrete object individuated from a cluster.

In a similar vein, the Slavic semelfactive

-nu attaches to bases that convey an iterative meaning, which typically describe quick repetitive events that often appear in series. Since a series is essentially a temporally structured plurality, its structure very much parallels that of a spatial cluster, just in a different domain (

Wągiel, 2023a). The result of the semelfactive derivation is a punctual verb that designates a singular individuated event.

Table 4 gives an overview of typical bases for unprefixed semelfactives in Polish.

Many semelfactives in Polish and other Slavic languages have onomatopoeic bases, e.g., the iterative verb

klikać ‘to click (repeatedly)’ describes series of clicking events, whereas its semelfactive counterpart

kliknąć ‘to click once’ denotes singular clicking eventualities.

8 Many other, not necessarily onomatopoeic, semelfactives also designate sounds, e.g.,

jęczeć ‘to moan (repeatedly)’ would denote series of moans and

jęknąć ‘to moan once’ describes singular moans.

9 In both cases, the bases represent events related to the emission of rapid sounds that often occur in series. Another class regards quick repetitive body moves, e.g,

machać ‘to wave (repeatedly)’ can only be true of a series of waving moves, whereas

machnąć ‘to wave once’ is only true of a single waving event. Finally, there are a number of semelfactives designating natural phenomena such as

buchać ‘to burst (repeatedly)’ and

buchnąć ‘to burst once’.

10 In all of the discussed cases,

-nu attaches to a base that describes a rapid event that can be easily iterated and often occurs in a series. The result is a punctual verb denoting a single instance of an (iterated) eventuality characterized by the base.

The second parallel concerns countability. It is well known that Slavic singulatives display hallmark properties of count nouns. They can be pluralized and they are compatible with basic cardinal numerals. This is illustrated by the Ukrainian examples in (13), where the nouns derived by

-in combine with the numeral ‘two’ and take the plural marker. In contrast, as one can see in (14), their aggregate counterparts are not countable and resist numeral modification and pluralization (modulo the well-known cases of the portioning and/or taxonomic coercion).

| (13) | a. | dvi | trav-yn-y |

| | | two | grass-in-pl |

| | | ‘two grass blades’ |

| | b. | dvi | ros-yn-y |

| | | two | dew-in-pl |

| | | ‘two dew drops’ | (Ukrainian) |

| (14) | a. | *dvi | trav-y |

| | | two | grass-pl |

| | | Intended: ‘two grasses’ |

| | b. | *dvi | ros-y |

| | | two | dew-pl |

| | | Intended: ‘two dews’ | (Ukrainian) |

Similar to singulatives, semelfactives are also countable and, thus, just like other perfective verbs, can be felicitously modified by multiplicatives. For instance, the Polish sentences in (15) describe situations in which Jacek gave two claps (15-a) and two burps (15-b) in the theater, respectively. Hence, in this case, the multiplicative counts singular events denoted by the semelfactive verbs. In contrast, though the corresponding iterative verbs are also compatible with multiplicatives, the domain of quantification is different since counting does not concern singular events but, rather, pluralities thereof. This is illustrated by the examples in (16), where the multiplicative ‘two times’ does not quantify over singular clapping (16-a) and burping (16-b) events, respectively, but, rather, over series thereof (see also

Wągiel, 2023a).

11 The parallel behavior of semelfactives and singulatives is expected if both categories involve individuation in terms of units.

| (15) | a. | Jacek dwa | razy | klas-ną-ł | w teatrze. |

| | | Jacek two | times | clap-nu-pst in theater |

| | | ‘Jacek clapped twice in the theater.’ |

| | b. | Jacek dwa | razy | bek-ną-ł | w teatrze. |

| | | Jacek two | times | burp-nu-pst in theater |

| | | ‘Jacek burped twice in the theater.’ | (Polish) |

| (16) | a. | Jacek dwa | razy | klaska-ł | w teatrze. |

| | | Jacek two | times | clap-pst in theater |

| | | ‘Jacek gave two series of claps in the theater.’ |

| | b. | Jacek dwa | razy | beka-ł | w teatrze. |

| | | Jacek two | times | burp-pst in theater |

| | | ‘Jacek gave two series of burps in the theater.’ | (Polish) |

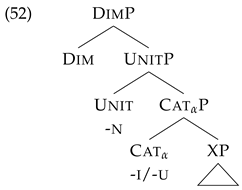

The third analogy concerns the syntactic position of

-in and

-nu. As argued in the literature, both appear to be very low in the structure. For

-in, it is below the number and probably just above the root inside the nP (

Geist et al., 2023;

Kagan & Nurmio, 2024). Likewise,

-nu seems to occupy a structurally low event internal position, below higher aspectual projections (

Arsenijević, 2006;

Biskup, 2023a,

2023b;

Borer, 2005b;

Milosavljević, 2023). This structural analogy suggests that the semantic contribution of

-in and

-nu relates to how an entity/event described by the root is individuated.

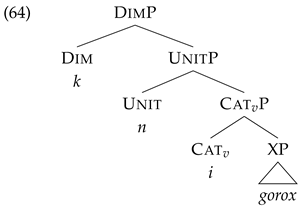

The fourth parallel concerns the fact that both singulative and semelfactive meanings show degree interactions; specifically, they can be targeted by scalar modifiers expressed morphologically within the structure of the noun and verb, respectively. In particular,

-in and

-nu can combine with pieces of morphology that can be viewed as encoding degree modification. In the case of singulatives, it is the diminutive suffix

-k, which conveys size modification, as illustrated by the Russian examples in (17).

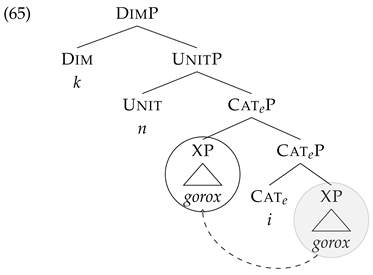

12| (17) | a. | gorox ∼ goroš-in-a ∼ goroš-in-k-a |

| | | pea.sg pea-in-sg pea-in-dim-sg |

| | | ‘peas (as a mass)’ ∼ ‘a small pea’ |

| | b. | žemčug ∼ žemčuž-in-a ∼ žemčuž-in-k-a |

| | | pearl.sg pearl-in-sg pearl-in-dim-sg |

| | | ‘pearl(s as a mass)’ ∼ ‘a pearl’ ∼ ‘a small pearl’ | (Russian, Kagan & Nurmio, 2024, p. 66) |

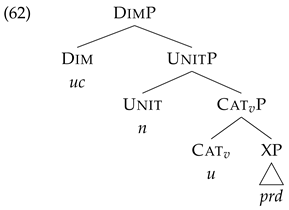

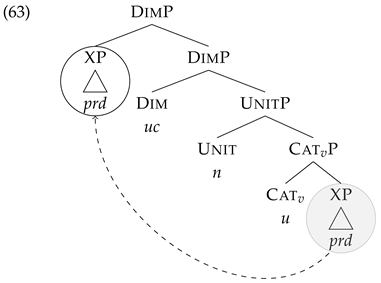

The semelfactive counterpart of this phenomenon is found in BCMS, where in a number of verbs,

-nu can co-occur with the verbal diminutive suffix

-uc, see (18). The resulting meaning involves the component of a small quantity (

Štarkl et al., 2025).

| (18) | a. | prdeti ∼ prd-nu-ti ∼ prd-uc-nu-ti |

| | | fart.inf.impf fart-nu-inf.pfv far-dim-nu-inf.pfv |

| | | ‘to fart’ ∼ ‘to fart once’ ∼ ‘to fart a little’ |

| | b. | grebati ∼ greb-nu-ti ∼ greb-uc-nu-ti |

| | | scratch.sg scratch-nu-inf.pfv scratch-dim-nu-inf.pfv |

| | | ‘to scratch’ ∼ ‘to scratch once’ ∼ ‘to scratch a little’ | (BCMS, Štarkl et al., 2025, p. 641) |

Relatedly, in Russian, many semelfactive verbs show an additional vocalic segment preceding

-nu, thus

-anu (e.g.,

Kuznetsova & Makarova, 2012;

Makarova & Janda, 2009). In some cases, there exist doublets such as those in (19), where the interpretation of

-anu verbs differs in a higher degree of intensity (force) of an action (sometimes described as expressivity) compared to their

-nu counterparts.

13 The contrasts could be interpreted as stemming from

-a encoding intensifier semantics.

| (19) | a. | stučat’ ∼ stuk-nu-t’ ∼ stuk-a-nu-t’ |

| | | knock.inf knock-nu-inf knock-ints-nu-inf |

| | | ‘to knock’ ∼ ‘to knock once’ ∼ ‘to knock once with force’ |

| | b. | rubit’ ∼ rub-nu-t’ ∼ rub-a-nu-t’ |

| | | chop.inf chop-nu-inf chop-ints-nu-inf |

| | | ‘to chop’ ∼ ‘to chop once’ ∼ ‘to chop once with force’ | (Russian, Kuznetsova & Makarova, 2012, p. 156) |

Notice that the placement of the diminutive (or intensifying) suffix differs depending on whether it combines with

-in or with

-nu. Specifically, the morpheme order in singulatives is

-in-dim but

-dim-nu in semelfactives. At first blush, this fact might seem somewhat unexpected under the explored analogy between

-in and

-nu. However, as I will show in

Section 5.5, both orders are compatible with contemporary approaches to morpheme order and can be derived from a single underlying structure. Thus, the difference in linearization is not a counterargument to their parallelism.

The final shared property to be discussed in this paper is that typically, neither singulatives nor semelfactives combine with derivational morphology that expresses plurality or pluractionality. In particular,

-in is generally incompatible with collectivizing affixes, whereas

-nu does not allow for secondary imperfectivization. Interestingly, however, there are several instances across Slavic when both of these combinations are possible. Specifically, Ukrainian allows for secondary collectives which display stacking of singulative and collective morphemes. For instance, in (20) the singulative

-yn attaches to the aggregate base and is then followed by the collectivizing suffix

-j (surfacing as

-nj due to phonological rules) (

Wągiel & Shlikhutka, 2023a). Admittedly, this phenomenon is very rare and was only reported in a few nouns in Ukrainian; nonetheless, it is attested and shows that the subsequent combination of singulativization and collectivization within one word formation is not impossible.

| (20) | popil ∼ popel-yn-a ∼ popel-yn-nj-a |

| | ash.sg ash-in-sg ash-in-coll-sg |

| | ‘ash’ ∼ ‘a speck of ash’ ∼ ‘(clustered specks of) ash’ | (Ukrainian, Wągiel & Shlikhutka, 2023a, p. 202) |

An analogous phenomenon was observed in BCMS, where several perfective

-nu verbs allow for secondary imperfectivization (

Milosavljević, 2023;

Štarkl et al., 2025). This is illustrated in (21), where

-nj is preserved despite the presence of the following suffix

-ava, which forms the secondary imperfective.

14 Again, cases like this are definitely very marginal, but I argue that they do show the combinatorial potential of the categories in question.

| (21) | svitati ∼ sva-nu-ti ∼ sva-nj-ava-ti |

| | dawn.inf.impf dawn-nu-inf.pfv dawn-nu-impf-inf |

| | ‘to dawn (impf)’ ∼ ‘to dawn (pfv)’ ∼ ‘to be dawning (impf)’ | (BCMS, Štarkl et al., 2025, p. 631) |

To conclude this section, the data discussed above indicate that the two categories in question do in fact show parallel behavior in grammar. In particular, I discussed five analogies. The first one concerns similar constraints on their formation. The second one is based on contrasts in terms of countability between singulatives/semelfactives and their corresponding aggregate/iterative counterparts. The third parallel concerns the low position in the structure. The fourth analogy regards degree interactions and compatibility with scalar modifiers and the last one concerns rare cases of stacking morphemes that, at first blush, seem to convey an opposite meaning. In face of the examined evidence, I conclude that a unified treatment of singulatives and semelfactives that would be based on a general individuating mechanism is desirable.

In the next section, I will consider a hypothesis that the singulative -in and the semelfactive -nu are not morphologically simplex. Rather, they are both structurally complex and involve two morphemes pronounced by the shared nasal component -n and a vocalic segment.