1. Introduction

Many researchers argue that there are correspondences between the nominal and the verbal domains in natural languages (e.g., see

Vendler, 1957;

Bach, 1986;

Langacker, 1987;

Krifka, 1989,

1992;

Filip, 1993a,

2000;

Verkuyl, 1993;

Jackendoff, 1996;

Mehlig, 1996;

Borer, 2005;

Nakanishi, 2007;

Kratzer, 2008;

den Dikken, 2010;

Dickey & Janda, 2015;

Kuhn, 2019 and

Simonović, 2022).

Most works approach these analogies from the semantic and aspectual perspectives, and the correspondences concern, for example, the mass-count distinction (

Bach, 1986), the property of being quantized versus non-quantized (

Krifka, 1992;

Filip, 2000), homogeneity versus heterogeneity (e.g.,

Mehlig, 1996) and plurality introduced by pluractionals, collective nouns or distributive numerals (

Henderson, 2017;

Kuhn, 2019). On one side, there are properties such as being quantized, singular, perfective, heterogeneous and being a particular entity, and on the other side, there are properties such as being non-quantized, (bare) plural, imperfective, cumulative, homogeneous and being a kind of entity.

There are also correspondences in the realm of morphophonology; e.g., consider

Simonović (

2022), who discusses two Slovenian derivational affixes, -

av and -

ov, used both in verbal and nominal forms. From a syntactic point of view, it has been argued that there are correspondences between the nominal and verbal domains, e.g., with respect to measure phrase constructions (

Nakanishi, 2007), the absence of the singular feature (

Kratzer, 2008) and case and verbal aspect or prefixation (

Szucsich, 2001,

2002;

Biskup, 2019) or with respect to extended projections (

den Dikken, 2010).

As for Slavic languages in particular,

Mehlig (

1996) draws parallels between the nominal and verbal domains in Russian with respect to homogeneity/heterogeneity and argues that the semelfactive aktionsart of verbs corresponds to the singulative form of mass nouns and that the delimitative aktionsart parallels the nominal partitive genitive. Similarly,

Filip (

2001) investigates parallels in semantic structure between noun phrases and verbal predicates in Russian, Polish and Czech and demonstrates how a nominal argument as an incremental theme interacts with the aspectual semantics of verbal predicates. According to

Borer (

2005), there is an operator–variable relation between Slavic perfective prefixes and nominal arguments, and the prefixes assign range to the nominal phrase occupying the specifier position of the aspectual phrase.

As to the typological perspective,

Dickey and Janda (

2015) argue that Slavic verbal prefixes parallel numeral classifiers that occur with nouns, e.g., in languages in East and Southeast Asia, in the fact that they bring about individuation. While numeral classifiers create a discrete referent out of a source noun, verbal prefixes individuate and classify events in the verbal domain.

In contrast to most approaches, which deal with analogies in Slavic languages from the semantic and aspectual points of view or restrict themselves to a specific type of aspectual marker, this article is concerned with the morphosyntactic structure of Slavic verbs. It tries to “push” the correspondences between the nominal and the verbal domains as far as possible and concentrates on aspectual affixes of verbal stems. It investigates the secondary imperfective suffix, as in (1a), the habitual marker, as in (1b), and the iterative morpheme, as illustrated in (1c).

| (1) | a. | o-mdl-e-wa-ć | (Polish) | | | | |

| | | about-faint-TH-SI-INF | | | | | |

| | | ‘to faint’ |

| | b. | děl-á-va-t | (Czech) | | | | |

| | | do-TH-HAB-INF | | | | | |

| | | ‘to tend to do’ |

| | c. | mig-a-ti | (BCMS) |

| | | blink-ITER-INF |

| | | ‘to blink’ |

Further, it is concerned with the semelfactive suffix, as in (2a), and prefixes: lexical, as shown by the spatial

vy- in (2b), and superlexical, as demonstrated by the delimitative

po- in (2c).

| (2) | a. | kop-n-ú-ť | (Slovak) | | | | |

| | | kick-SEML-TH-INF | | | | | |

| | | ‘to kick once’ |

| | b. | vy-nes-ti | (Russian) | | | | |

| | | out-carry-INF | | | | | |

| | | ‘to carry out sth.’ |

| | c. | po-govor-i-ť | (Russian) |

| | | DEL-speak-TH-INF |

| | | ‘to speak for a while’ |

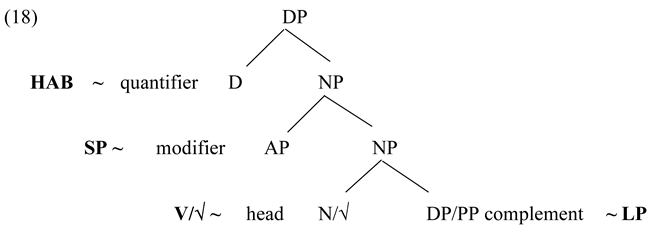

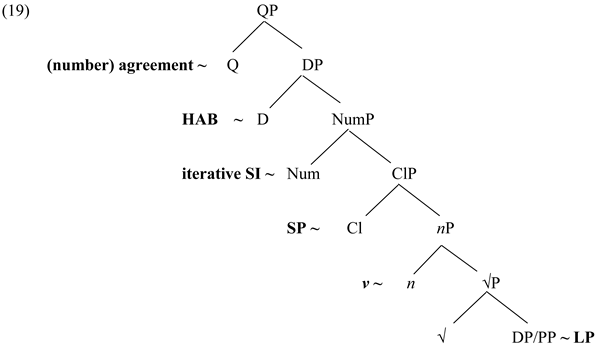

To the best of my knowledge, there has been no attempt in the literature on Slavic languages to investigate morphosyntactic analogies between all verbal aspectual markers and the nominal domain. The article argues that the secondary imperfective suffix with an iterative meaning parallels the nominal number projection and that the habitual suffix is the counterpart of the nominal determiner. The internal iterative -

a is analyzed as a realization of the verbal categorizing head, hence it is analogous to the categorizing head of nouns. The semelfactive marker is a parallel of the singulative (or diminutive) affix of the nominal domain. Verbal prefixes correspond to nominal classifiers. Moreover, superlexical prefixes parallel adjectival modifiers of nouns, and lexical prefixes can be viewed as the counterpart of the nominal complement. This proposal follows the Distributed Morphology framework (see e.g.,

Halle & Marantz, 1993;

Harley & Noyer, 1999).

The proposal is meant to hold for all Slavic languages, albeit with certain variations. Specifically, in contrast to Czech and Slovak, which have dedicated habitual markers for the realization of the habitual head, other Slavic languages use either a null marker or license the habitual projection at a distance (see

Biskup, 2024;

Klimek-Jankowska et al., 2025;

Biskup, To appear). Even if all Slavic languages have a dedicated marker for a particular verbal head, the languages can differ in the phonological form of the specific marker(s). Thus, while all Slavic languages employ the semelfactive (diminutive) suffix -

n and the vowel -

a for spelling out the verbalizing head

v with the iterative meaning, verbal prefixes and secondary imperfective suffixes are different to a certain extent.

Since the Slavic aspect system is very specific (see

Dahl, 1985, for the “Slavic-style” aspect)—featuring both lexical and viewpoint aspect—the analysis proposed in this article cannot be applied to non-Slavic languages in its entirety. Certain parts of the analysis, however, can be applied to non-Slavic languages. For instance, given that Germanic languages also have a difference between resultative and aspectual prefixes/particles, the part of the current analysis on nominal complements and adjectival modifiers could be applied to them (see

Stiebels, 1996;

Svenonius, 2004;

Gehrke, 2008;

Ramchand, 2008;

Biskup & Putnam, 2012 and

McIntyre, 2015). This and classifier analysis of verbal prefixes find parallels in East Asian and Southeast Asian languages since certain classifiers of Mandarin, Cantonese and Thai fulfill a function in both the nominal and verbal domains and the classifier phrase is selected by the appropriate verb (e.g., see

Matthews & Leung, 2004, and

Dickey & Janda, 2015).

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. The next section is concerned with properties of the nominal domain.

Section 3 discusses morphosyntactic properties of Slavic predicates and introduces five aspectual markers of the verbal domain. The core of the article can be found in

Section 4. It aims to find correspondences of the verbal aspectual affixes in the nominal domain.

Section 5 concludes the article.

2. The Nominal Domain

Given

Abney’s (

1987) DP hypothesis, the traditional analysis of noun phrases looks like (3a). The head noun represents a property that is predicated of an individual variable, e.g., the property of being a student: STUDENT(x), as in (3b). Nouns optionally have a modifier, AP, which adds another predicate, e.g., OLD(X), as shown in (3b). According to the standard analysis (

Barwise & Cooper, 1981), the head D is a quantifier—e.g., represented by

all,

a, as in (3b)—which expresses the relation between its restrictor, (OLD) STUDENT, and its nucleus. D is also usually assumed for Slavic languages, which are mostly articleless; e.g., see

Franks (

1995),

Progovac (

1998),

Rutkowski (

2002),

Pereltsvaig (

2007),

Bailyn (

2012),

Veselovská (

1998,

2014),

Šimík (

2016) and

Geist (

2021).

Nouns can also have a complement DP or PP, as in a student of architecture, which introduces an entity different from the individual of the dominating DP (except anaphoric expressions).

Nowadays, the extended projection of nouns is more articulated. In the Distributed Morphology approach, the head N is replaced with the root √ and the category-defining head

n (e.g.,

Harley, 2005). Certain approaches assume an articulated structure for modifiers; e.g., consider the cartographic approach of

Cinque (

2010), in which DP-internal adjectives are generated in rigidly ordered functional projections.

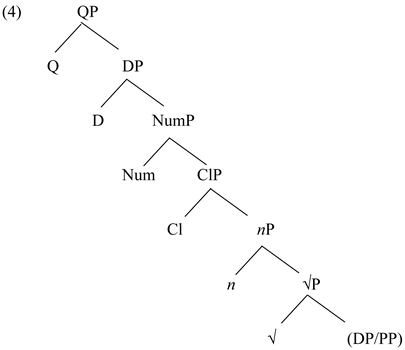

It has been argued that number is realized as the head of a functional category NumP in nominal phrases (e.g., see

Ritter, 1993;

Wiltschko, 2021 and

Corbett, 2000 for an overview of number exponents). Some researchers assume that there are, in fact, two distinct projections for quantifying elements. According to

Kratzer (

2008), in addition to lexical cumulativity (pluralization), there is a plural projection above the noun (NP) and a higher plural projection above DP. Similarly,

Veselovská (

2018), following

Skrabalova (

2004), postulates two quantifying phrases for Czech: NumP, positioned above

nP, and QP, placed above DP. Moreover,

Wiltschko (

2008) proposes that in some languages, the plural marker can be a modifier that attaches directly to the root.

Since classifiers individuate and produce forms that serve as an input to counting or measuring, they are usually assumed to occur in a projection between

nP and NumP (e.g.,

Zhang, 2013;

Wiltschko, 2021), which is labeled, for example, as Cl(assifier)P, UnitP or DivP.

Gender is an inherent property of nouns, hence it is often treated as a property of the nominal head N or the category-defining

n (e.g., see

Kramer (

2015); furthermore, there are also approaches assuming another, higher gender projection, such as

Puškar’s (

2017) analysis of hybrid agreement in Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian). Simplifying somewhat and abstracting away from the specifics of particular approaches, the extended projection of nominal phrases looks like (4).

Having introduced basic properties of the extended projection of nominals, let us now move to the verbal domain.

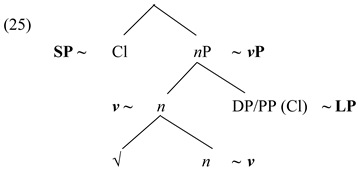

3. The Verbal Domain

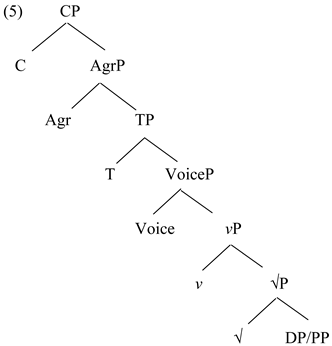

The (more or less) standard analysis of the extended projection of a transitive verb is depicted in (5); e.g., see

Corver (

2013) and

Harley (

2013). The internal argument (direct object) occurs in the complement position of the root. Mostly, it is a noun or a prepositional phrase but it can also be a result phrase (

Ramchand, 2008), in which Slavic lexical prefixes are assumed to merge. The root is verbalized by the little

v head (

Marantz, 1997). The external argument—typically, the subject with the agent theta role (not shown in (5))—is introduced in the specifier position of the voice phrase (VoiceP, e.g.,

Harley, 2005). The tense projection specifies tense properties of the predicate and the agreement projection encodes verbal agreement properties. Before splitting, these two phrases were labeled as the inflectional phrase (IP). The complementizer phrase (CP) hosts complementizers and is mostly responsible for sentence mood properties.

For some languages, including Slavic, an aspectual phrase (AspP) is assumed. This phrase is either located between the verbal projection (VoiceP) and TP (e.g.,

Svenonius, 2004;

Gehrke, 2008;

Gribanova, 2015;

Biskup, 2019) or below the projection introducing the external argument (

Romanova, 2004;

MacDonald, 2006), which would be between

vP and VoiceP in (5). The structure can be more articulated, e.g., as proposed by

Cinque (

1999). Among others, Cinque assumes projections for habituality and iterativity (repetition), which are also relevant to our discussion.

![Languages 10 00274 i003 Languages 10 00274 i003]() |

A verb can have one or more prefixes; consider the lexical prefix

u- ‘at’ in (6b). The (prefixed) root is mostly followed by an overt verbalizing morpheme, e.g., by -

á, as in (6b). Prefixed, i.e., perfective, stems can be imperfectivized by a secondary imperfective morpheme, as illustrated by -

vá in (6b). Moreover, in Czech and Slovak, secondary imperfective stems can combine with a habitual suffix, as demonstrated by -

va in example (6b). There is debate about the status of theme vowels in Slavic. According to some researchers, the vowel -

a preceding the tense/participial suffix is an independent (conjugation) marker (e.g.,

Gribanova, 2015;

Klimek-Jankowska & Błaszczak, 2022,

2023;

Kwapiszewski, 2022;

Quaglia et al., 2022;

Matushansky, 2024). According to Biskup (To appear), the vowel -

a preceding the tense/participial -

l suffix in cases such as (6b) belong to the habitual marker in Czech and Slovak in contrast to Russian and Polish. Finally, the outermost suffix -

i represents the masculine plural agreement. This suffix would be located in the Agr head of (5).

In what follows, I concentrate on the aspectual affixes. There are at least five types: verbal prefixes, the secondary imperfective suffix, the semelfactive morpheme, the iterative marker -

a and the habitual suffix. Let us begin with verbal prefixes. They perfectivize the stem to which they attach, as in (7), and make the predicate quantized. Many approaches distinguish between two basic types of prefixes in Slavic, lexical (resultative, internal) and superlexical (aktionsart and external); consider, for example,

Isačenko (

1962),

Babko-Malaya (

1999),

Jabłońska (

2004),

Svenonius (

2004),

Romanova (

2006),

Szucsich (

2007),

Kagan (

2015) and

Marušič et al. (

2025). These two types differ—at least by tendency—with respect to their meanings, argument structure effects, stacking and the possibility of secondary imperfectivization. These differences are usually assumed to arise from distinct base positions. While lexical prefixes are taken to merge into the complement of the root, superlexical prefixes are assumed to merge into a higher position above

vP or in a higher position in

vP (depending on the particular approach).

Lexical prefixes bring about spatial or idiosyncratic meanings, as in (7b), whereas superlexical prefixes have an adverbial-like (aktionsart) meaning, as shown by the prefix

po-, which delimits the event of thinking in (7c). Also, in contrast to the unprefixed predicate

dumať, ‘to think’, in (7a) or the superlexically prefixed verb

podumať, ‘to think’, in (7c), the lexically prefixed

vydumať, ‘to make up’, requires a direct object.

| (7) | a. | dumaťIPF | (Russian) | | | | |

| | | think | | | | | |

| | | ‘to think’ |

| | b. | vy-dumaťPF | | | | | |

| | | out-think | | | | | |

| | | ‘to make up sth.’ |

| | c. | po-dumaťPF |

| | | by-think |

| | | ‘to think for a while’ |

Predicates with a lexical prefix can always be secondarily imperfectivized, as in (8), in contrast to superlexical prefixes, which are more restricted in this respect. Contrary to perfective verbs, such as

vydumať, ‘to make up’, in (7b), predicates with the secondary imperfective suffix, such as

vydum-yv-ať, ‘to (be) make(ing) up’, in (8), do not grant reaching the result state (except for in the special factual usage, in which it is assumed that the result has been reached and the imperfective form is used to stress the action leading to the result state; e.g., see

Smith, 1997). In other words, forms like (8) have a progressive (partitive, ongoing) meaning. Secondary imperfective predicates can also have a pluractional (iterative) meaning, according to which the event of making up in (8) is repeated several times or habitually (e.g.,

Comrie, 1976;

Dickey, 2000;

Klimek-Jankowska et al., 2025). With respect to the secondary imperfective suffix, I follow

Romanova (

2004),

Tatevosov (

2015),

Mueller-Reichau (

2021) and

Biskup (

2023a,

2025), who argue that the secondary imperfective suffix is located below the phrase introducing the external argument, i.e., between

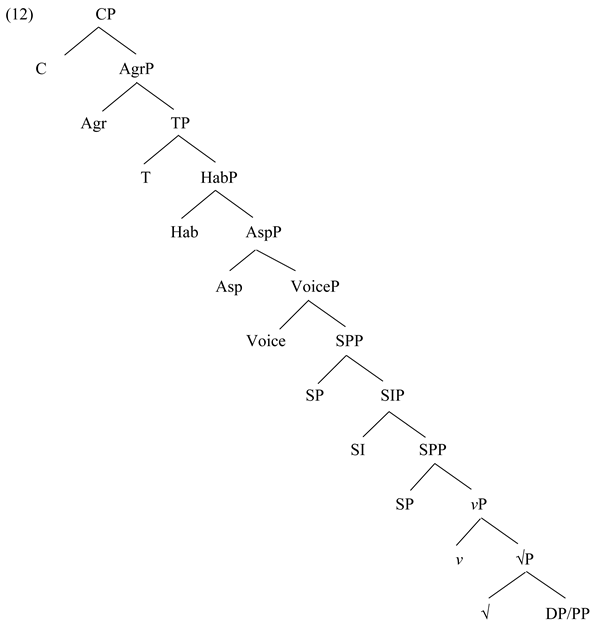

vP and VoiceP in structure (5).

| (8) | vy-dum-yv-a-ťIPF | | (Russian) | | | | |

| | out-think-SI-TH-INF | | | | | | |

| | ‘to make up sth.’ | | | | | | |

| | ‘to be making up sth.’ | | | | | | |

In contrast to South Slavic languages, North Slavic languages also have an overt habitual marker (e.g.,

Jabłońska, 2007;

Karlík, 2017;

Biskup, 2024;

Filip, To appear), as illustrated in examples (6b) and (9). This suffix derives imperfective predicates from imperfective stems, that is,

spáva(

ť), ‘to tend to sleep’, can be derived from

spa(

ť), ‘to sleep’, in the case of (9).

| (9) | sp-á-va-ťIPF | | (Slovak) | | | | |

| | sleep-TH-HAB-INF | | | | | | |

| | ‘to tend to sleep’ | | | | | | |

Contrary to other North Slavic languages, in Czech and Slovak, the formation of habitual predicates is fully productive (e.g.,

Filip, 1993b;

Esvan, 2007;

Karlík, 2017;

Nübler, 2017). Moreover, as already shown in (6b), Czech—and Slovak, too—can combine the secondary imperfective suffix with the overt habitual marker. It has been argued for Slavic languages that the habitual projection (HabP) occurs below the tense phrase (

Biskup, 2023a,

2024), i.e., between VoiceP and TP in (5).

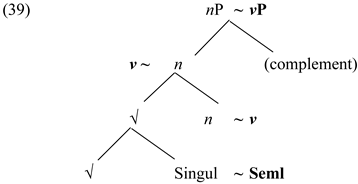

The next aspectual marker—the semelfactive suffix—attaches directly to the root and derives perfective predicates; consider the Polish example in (10). According to the descriptive literature, the suffix consists of -

n and some vowel (which is the present or past theme); see

Laskowski (

1979),

Švedova (

1980),

Karlík et al. (

1995) and

Toporišič (

2000), and for a diachronic point of view, see

Wiemer and Seržant (

2017).

| (10) | puk-n-ą-ćPF | | (Polish) | | | | |

| | knock-SEML-TH-INF | | | | | | |

| | ‘to knock once’ | | | | | | |

The semelfactive suffix brings about the instantaneous (single-stage event) interpretation (see

Smith, 1997) and for North Slavic languages, it is mostly assumed that an event denoted by the semelfactive predicate is singular (e.g.,

Isačenko, 1962;

Armoškaitė & Sherkina-Lieber, 2008), atomic (

Łaziński, 2020) or both (

Biskup, 2023a). The situation in South Slavic languages is slightly different. Some authors argue that it brings about atomicity (e.g.,

Arsenijević, 2006), while other researchers prefer diminutivity (e.g.,

Štarkl et al., 2025).

The semelfactive marker contrasts with the iterative suffix -

a, which also attaches directly to the root, as shown in (11). In contrast to the semelfactive example (10), predicates with the iterative -

a, as in (11), are imperfective and denote several occurrences of a particular event, as shown by the translation. This is in line with cross-linguistic findings, e.g., by

Wood (

2007), who argues that semelfactives commonly occur with (event-internal) pluractionality.

| (11) | puk-a-ćIPF | | (Polish) | | | | |

| | knock-ITER-INF | | | | | | |

| | ‘to knock repeatedly’ | | | | | | |

Building on this discussion, a more articulated verbal structure with the relevant projections for aspectual affixes looks like (12). A habitual suffix realizes the head Hab and a secondary imperfective suffix spells out the head SI. Since superlexical prefixes can merge either before or after a secondary imperfective suffix in Slavic languages, there are two phrases (SPP) for them in (12). The aspectual head (Asp) is phonologically empty, and semantically, it encodes the relation between the event time and the reference time.

The next section ties the verbal and nominal domains together. It aims to find correspondences to aspectual affixes in the nominal domain.

5. Conclusions

In this article, I discussed morphosyntactic analogies between the verbal and nominal domains in Slavic languages and the focus was mainly on aspectual properties of Slavic predicates. Building on syntactic and semantic properties of particular affixes and on the previous literature, I argued for the following correspondences between verbal and nominal morphemes. The acategorial root can merge with the verbal categorizing v or with the nominalizing head n. I have argued that Slavic languages, too, have event-internal and event-external pluractionality and that the iterative suffix -a is related to event-internal pluractionality and spells out the verbal categorizing head.

In contrast, the iterative secondary imperfective morpheme is responsible for event-external pluractionality and can be viewed as a counterpart of the (pluralizing) number head of the nominal domain. Before the merger of a categorizing head, the acategorial root can merge with the semelfactive (diminutive) suffix -n or with its nominal counterpart, a singulative (diminutive) marker such as -in or -ink. The verbal categorizing head is then spelled out by the infinitival theme vowel—whose form depends on the particular Slavic language—e.g., by -u in Ukrainian, Russian and Serbo-Croatian, -ą in Polish, -ou in Czech, -ú in Slovak and -i in Slovenian.

For pluralization, applying the iterative secondary imperfective suffix, individuation is necessary. This effect is brought about by prefixes in the verbal domain, which quantize the predicate they attach to. Thus, with respect to individuation, verbal prefixes are analogous to classifiers of the nominal domain. Moreover, in their adverbial function, superlexical prefixes parallel adjectival modifiers of nouns. In contrast, I have treated lexical prefixes as the counterpart of nominal complement. To maintain the morphosyntactic (hence, compositional) analogy between classifiers and all verbal prefixes, I have assumed that verbal prefixes always enter the derivation after the categorizing head v, to which the root is adjoined.

As for the overt habitual morpheme present in North Slavic languages, I have analyzed it as the verbal parallel of the nominal determiner because of its quantificational properties and its high structural position.