Translanguaging and Second-Language Reading Proficiency: A Systematic Review of Effects and Methodological Rigor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Translanguaging and Second-Language Reading

2.2. Translanguaging and Methodological Rigor

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Domain and Scope of the Study

3.2. Literature Search

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Examined the impact of translanguaging—planned or explicitly claimed;

- Involved second-language (L2) learners as participants;

- Reported outcomes related to reading comprehension, reading proficiency, or reading development;

- Employed an empirical research design;

- In the case of quantitative studies, provided sufficient statistical data for effect size calculation (e.g., means, standard deviations, t values, F values, or correlation coefficients);

- Were published between 1980 and 2024, corresponding to the period after the term translanguaging was first coined by Cen Williams.

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Investigated aspects other than reading development (e.g., motivation, identity affirmation, writing, speaking, etc.).

- Examined the impact of prior language resources (e.g., L1 glosses) on L2 reading but did not adopt a holistic approach (i.e., did not use the term translanguaging, entire linguistics repertoire, asset, or resource).

- Addressed multiple components of L2 literacy (e.g., fluency, content knowledge, or transfer), but only one component was related to reading comprehension; in such cases, only the relevant reading-related data were retained and the rest were excluded.

- Did not provide sufficient empirical data to support the quantitative analysis (e.g., lacked results, effect sizes, or clear methodological descriptions).

- Theoretical or conceptual papers without empirical investigation.

- Published in journals lacking peer-review transparency or inclusion in recognized academic indexes.

3.2.3. Search Strategy

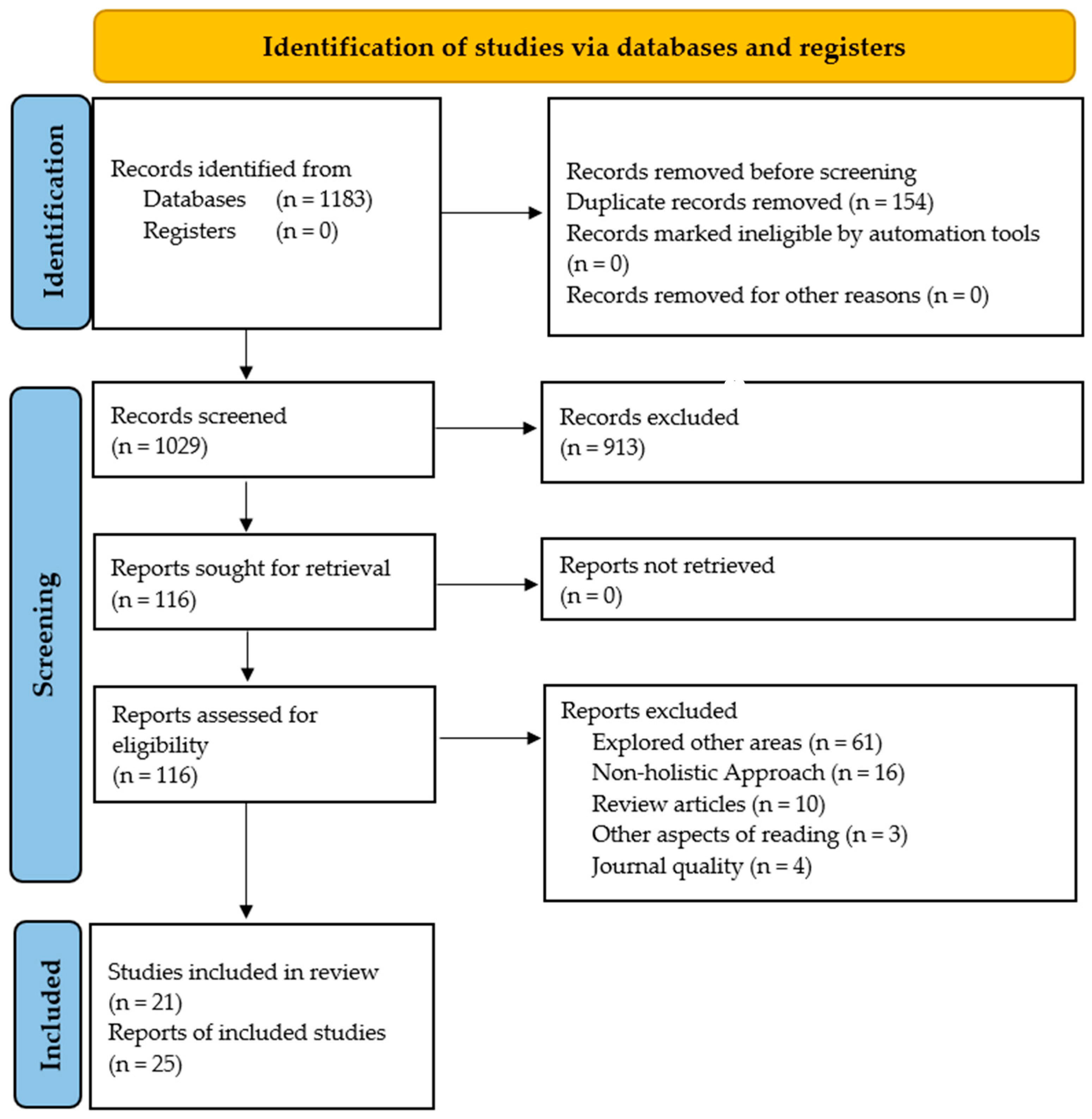

3.3. Selection Process

3.4. Screening

3.5. Data Extraction and Data Items

- An a priori power analysis—specifically, whether they indicated the number of participants required for the planned analysis, the statistical tests being powered, the number of outcomes assessed, and other relevant details;

- The actual number of participants in these studies;

- The presence/absence of a comparison group;

- Instrument reliability;

- An assumption check for the selected analysis;

- Details of the study outcome, such as mean values, standard deviations, effect sizes, and t and F values, among other relevant parameters.

- Depth/triangulation: More than one source of data collection is reported.

- Transparency: All the data collected is analyzed/reported.

- Coding details are provided.

- Coder reliability: Coding/re-coding is performed or more than one coder codes the data.

- Instrument reliability: If an instrument (questionnaire/structured interview) is used, its piloting/reliability is reported.

- Inter-rater reliability: Member/participant checking is reported, and the reliability index or percentage agreement is provided.

3.6. Synthesis

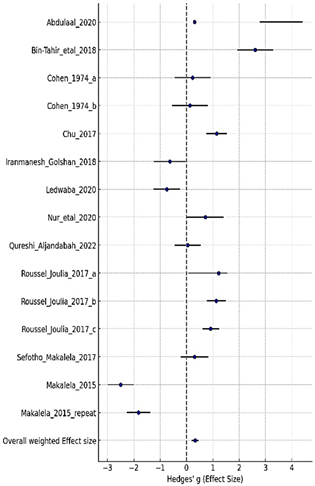

4. Results

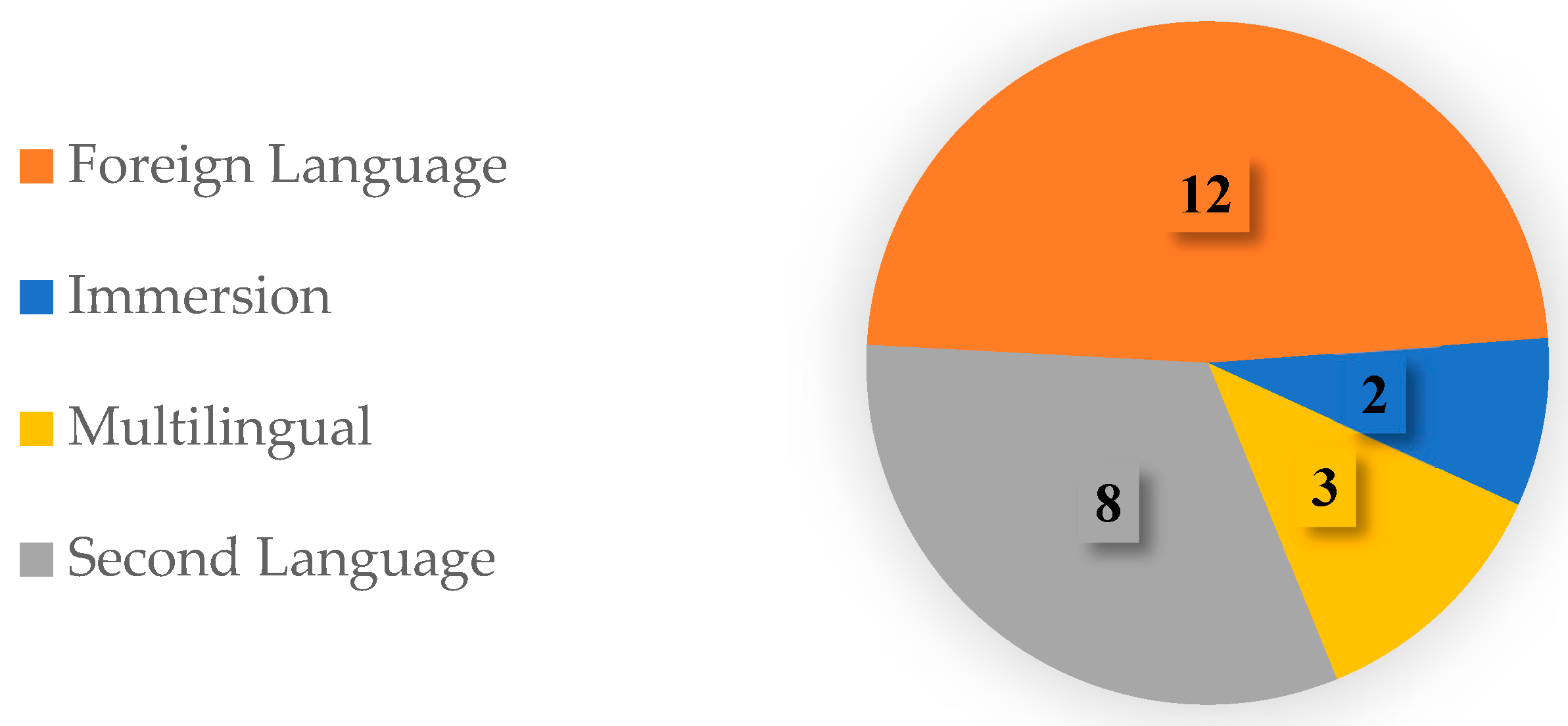

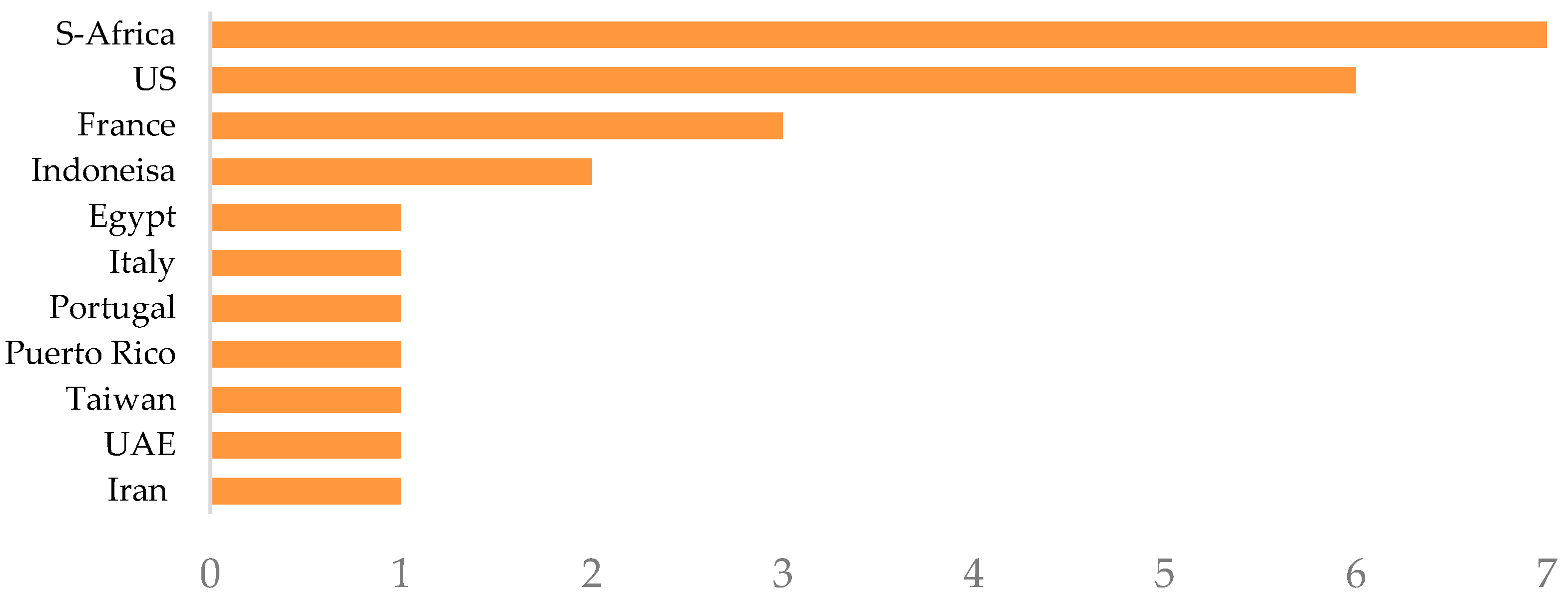

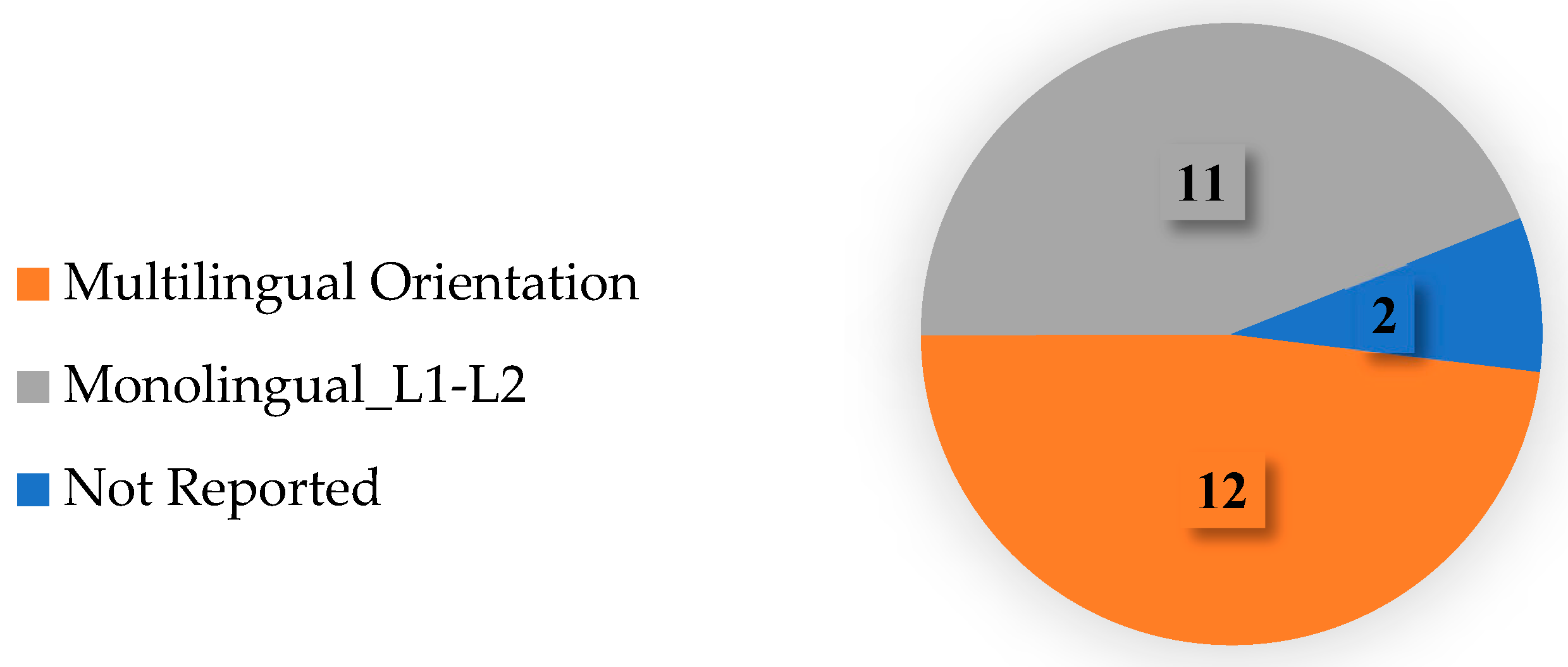

Summary Characteristics of Included Studies

- Studies showing significant positive effects (e.g., Bin-Tahir et al., 2018; Chu, 2017; Roussel et al., 2017, 1 and 2).

- Studies exhibiting strong negative effects (e.g., Makalela, 2015, 1 and 2; Ledwaba, 2020; Iranmanesh & Golshan, 2018).

- Samples showing no significant effects (e.g., Cohen, 1974; Qureshi & Aljanadbah, 2022; Sefotho & Makalela, 2017).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Prominent journals in the field now require a complete reporting of descriptive and inferential statistics, including confidence intervals, exact p-values, and effect sizes (see author guidelines for Language Learning, TESOL Quarterly, and SSLA).

- Researchers are encouraged to share datasets, questionnaires, coding schemes, instruments, etc., on publicly accessible platforms, including the Instruments for Research into Second Languages (IRIS: https://www.iris-database.org) and the Open Science Framework (OSF: https://osf.io).

- A new journal Research Methods in Applied Linguistics exclusively focusing on research accuracy and rigor has been launched.

- The journal Language Learning has introduced “registered reports”, a new category for publication that requires authors to submit the rationale, proposed methods, and analytical procedures for review before data collection.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdulaal, M. A. (2020). A shift from a monoglossic to a heteroglossic view: Metalinguistic stego-translanguaging lens approach. Arab World English Journal, 11(4), 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hoorie, A. H., & Vitta, J. P. (2019). The seven sins of L2 research: A review of 30 journals’ statistical quality and their CiteScore, SJR, SNIP, JCR Impact Factors. Language Teaching Research, 23(6), 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, E. C. (2017). Re-examining teacher translanguaging: An ecological perspective. Bilingual Research Journal, 40(2), 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Tahir, S. Z., Saidah, U., Mufidah, N., & Bugis, R. (2018). The impact of translanguaging approach on teaching Arabic reading in a multilingual classroom. Ijaz Arabi Journal of Arabic Learning, 1(1), 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, K. S., & Sambolín Morales, A. N. (2016). Using university students’ L1 as a resource: Translanguaging in a Puerto Rican ESL classroom. Bilingual Research Journal, 39(3–4), 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, E. (2018). Translanguaging in higher education: Using several languages for the analysis of academic content in the teaching and learning process. Language Learning in Higher Education, 8(1), 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Pedagogical translanguaging: An introduction. System, 92, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Open Science. (n.d.). Center for open science. Available online: https://www.cos.io/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Ceprano, M. A., Shea, M. E., & Gandt, A. N. (2018). Reading bilingual books: Students learn English while acquiring knowledge about American cultural traditions and places. School–University Partnerships, 11(1), 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, H., Brown, J., & Koryakina, A. (2024). Topics, publication patterns, and reporting quality in systematic reviews in language education. Lessons from the international database of education systematic reviews (IDESR). Applied Linguistics Review, 15(4), 1645–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, H., & Murphy, V. (2021). Multilingual learners, linguistic pluralism and implications for education and research. In E. Macaro, & R. Woore (Eds.), Debates in second language education (1st ed., pp. 66–88). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C. S. (2017). Translanguaging in reading comprehension assessment: Implications on assessing literal, inferential, and evaluative comprehension among ESL elementary students in Taiwan. NYS TESOL Journal, 4(2), 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A. D. (1974). The culver city Spanish immersion program: The first two years. The Modern Language Journal, 58(3), 95–103. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/323824 (accessed on 10 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- CONSORT Group. (n.d.). Consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT). Available online: https://www.consort-statement.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- García, O. (2011). Translanguaging in bilingual education. In A. S. Canagarajah (Ed.), The routledge handbook of migration and language (pp. 140–150). Routledge. Available online: https://ofeliagarciadotorg.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/translanguaging-in-bilingual-education.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- García, O., & Otheguy, R. (2020). Plurilingualism and translanguaging: Commonalities and divergences. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(1), 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gass, S., Loewen, S., & Plonsky, L. (2021). Coming of age: The past, present, and future of quantitative SLA research. Language Teaching, 54, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, W. (2009). Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. L. (2019). Teaching and researching reading (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawras, S. (1996). Towards describing bilingual and multilingual behavior: Implications for ESL instruction [Unpublished thesis, University of Minnesota]. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, T. (2001). Mixing beginners and native speakers in minority language immersion: Who is immersing whom? The Canadian Modern Language Review, 57(3), 443–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S. (2013). Strengthening bi-literacy through translanguaging pedagogies. In The 62nd literacy research association yearbook (pp. 234–247). Literacy Research Association. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X., & Chalmers, H. (2023). Implementation and effects of pedagogical translanguaging in EFL classrooms: A systematic review. Languages, 8(3), 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungwe, V. (2019). Using a translanguaging approach in teaching paraphrasing to enhance reading comprehension in first-year students. Reading & Writing, 10(1), a216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, F., & Golshan, M. (2018). Mother tongue as an asset in developing L2 reading comprehension skill among Iranian EFL learners. International Journal of Social Science Research, 6(1), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. (n.d.). JASP (Version 0.17.2) [Computer software]. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(1), 7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, R. G. (1994). The role of mental translation in second language reading. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 16, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. J. Y., & Weng, Z. (2022). A systematic review on pedagogical translanguaging in TESOL. TESL-EJ, 26(3), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H. J., & Schallert, D. L. (2016). Understanding translanguaging practices through a biliteracy continua framework: Adult biliterates reading academic texts in their two languages. Bilingual Research Journal, 39(2), 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledwaba, M. R. (2020). Translanguaging as a pedagogical strategy to improve the reading comprehension of Grade 4 learners in a Limpopo primary school [Master’s dissertation, University of Pretoria]. University of Pretoria Repository. Available online: https://repository.up.ac.za/ (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Legarreta, D. (1977). Language choice in bilingual classrooms. TESOL Quarterly, 11(1), 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G., Jones, B., & Baker, C. (2012). Translanguaging: Origins and development from a pedagogical perspective. Educational Research and Evaluation, 18(7), 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. E., Lo, Y. Y., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2020). Translanguaging pedagogy in teaching English for academic purposes: Researcher-teacher collaboration as a professional development model. System, 92, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, S., Gönülal, T., Isbell, D. R., Ballard, L., Crowther, D., Lim, J., Maloney, J., & Tigchelaar, M. (2020). How knowledgeable are Applied Linguistics and SLA researchers about basic statistics? Data from North America and Europe. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(4), 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, S., & Hui, B. (2021). Small samples in instructed second language acquisition Research. The Modern Language Journal, 105, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacSwan, J. (2017). A multilingual perspective on translanguaging. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1), 167–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, A., Paltridge, B., Phakiti, A., Wagner, E., Starfield, S., Burns, A., Jones, R. H., & De Costa, P. I. (2016). TESOL Quarterly research guidelines. TESOL Quarterly, 50(1), 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makalela, L. (2015). Translanguaging as a vehicle for epistemic access: Cases for reading comprehension and multilingual interactions. Per Linguam, 31(1), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Beltrán, M., Montoya-Ávila, A., García, A. A., Madigan Peercy, M., & Silverman, R. (2019). ‘Time for una pregunta’: Understanding Spanish use and interlocutor response among young English learners in cross-age peer interactions while reading and discussing text. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(1), 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Roldán, C. M., & Sayer, P. (2006). Reading through linguistic borderlands: Latino students’ transactions with narrative texts. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 6(3), 293–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbirimi-Hungwe, V. (2016). Translanguaging as a strategy for group work: Summary writing as a measure for reading comprehension among university students. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 34(3), 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musk, N. (2010). Code-switching and code-mixing in Welsh bilinguals talk: Confirming or refuting the maintenance of language boundaries? Language, Culture and Curriculum, 23, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, R., Namrullah, Z., Syawal, & Nasrullah, A. (2020). Enhancing reading comprehension through translanguaging strategy. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 11(6), 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, F. L., & Plonsky, L. (2010). Meta-analysis in second language research: Choices and challenges. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 30, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plonsky, L. (2023). Sampling and generalizability in Lx research: A second-order synthesis. Languages, 8(1), 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plonsky, L., & Brown, D. (2015). Domain definition and search techniques in meta-analyses of L2 research (Or why 18 meta-analyses of feedback have different results). Second Language Research, 31(2), 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plonsky, L., & Oswald, F. L. (2012). How to do a meta-analysis. In A. Mackey, & S. M. Gass (Eds.), Research methods in second language acquisition: A practical guide (pp. 275–295). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilutskaya, M. (2021). Examining pedagogical translanguaging: A systematic review of the literature. Languages, 6(4), 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M. A., & Aljanadbah, A. (2022). Translanguaging and reading comprehension in a second language. International Multilingual Research Journal, 16(4), 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, S., Joulia, D., Tricot, A., & Sweller, J. (2017). Learning subject content through a foreign language should not ignore human cognitive architecture: A cognitive load theory approach. Learning and Instruction, 52, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefotho, M. P., & Makalela, L. (2017). Translanguaging and orthographic harmonisation: A cross-lingual reading literacy in a Johannesburg school. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 35(1), 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, G. H., & Hashim, F. (2006). Use of L1 in L2 reading comprehension among tertiary ESL learners. Reading in a Foreign Language, 18, 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- SPIRIT Group. (n.d.). SPIRIT: Standard protocol items: Recommendations for interventional trials. Available online: https://www.spirit-statement.org/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to … assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17(6), 596–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, N., & Wigglesworth, G. (2003). Is There a role for the use of the L1 in an L2 setting? TESOL Quarterly, 37(4), 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffers-Daller, J. (2024). Translanguaging: What is it beyond smoke and mirrors? Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, T. A. (1997). First and second language use in reading comprehension strategies of Japanese ESL students. Tesl-EJ, 3(1). Available online: http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Vaish, V. (2019). Translanguaging pedagogy for simultaneous biliterates struggling to read in English. International Journal of Multilingualism, 16(3), 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. (2002). Ennill iaith: Astudiaeth o sefyllfa drochi yn 11–16 oed [A language gained: A study of language immersion at 11–16 years of age]. School of Education. Available online: https://primo.aber.ac.uk/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma994678743402418&context=L&vid=44WHELF_ABW:44WHELF_ABW_VU1 (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Yadav, D. (2022). Criteria for good qualitative research: A comprehensive review. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 31, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafele, S. (2021). Translanguaging for academic reading at a South African university. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 39(4), 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., Kiramba, L. K., & Wessels, S. (2021). Translanguaging for biliteracy: Book reading practices in a Chinese bilingual family. Bilingual Research Journal, 44(1), 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Research paper | Dissert/thesis | Conf. proceeding | Book chapter |

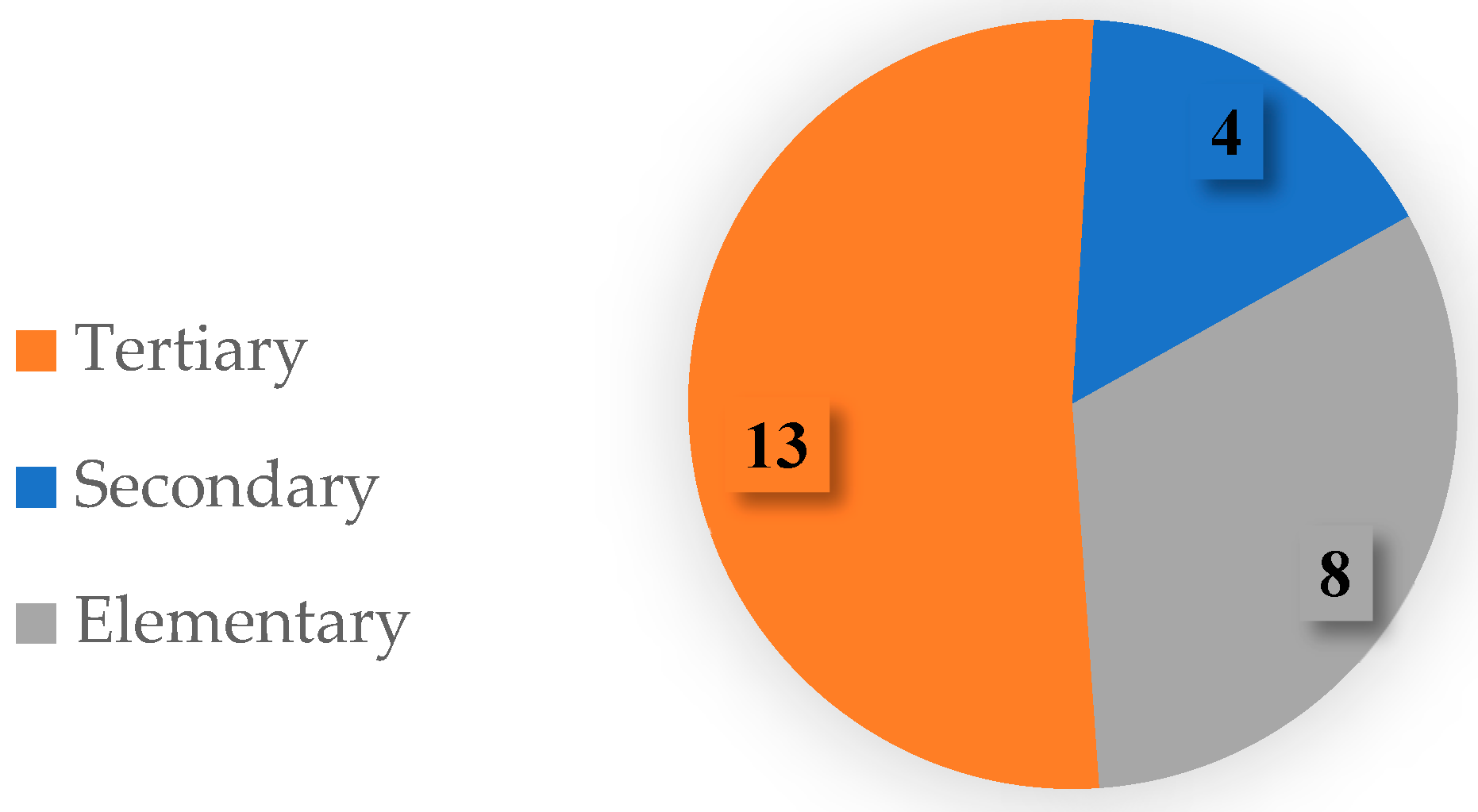

| Setting | |||

| Second language | Foreign language | Multilingual | |

| Location | |||

| Research Methodology | |||

| Quantitative | Qualitative | Mixed | |

| Method | |||

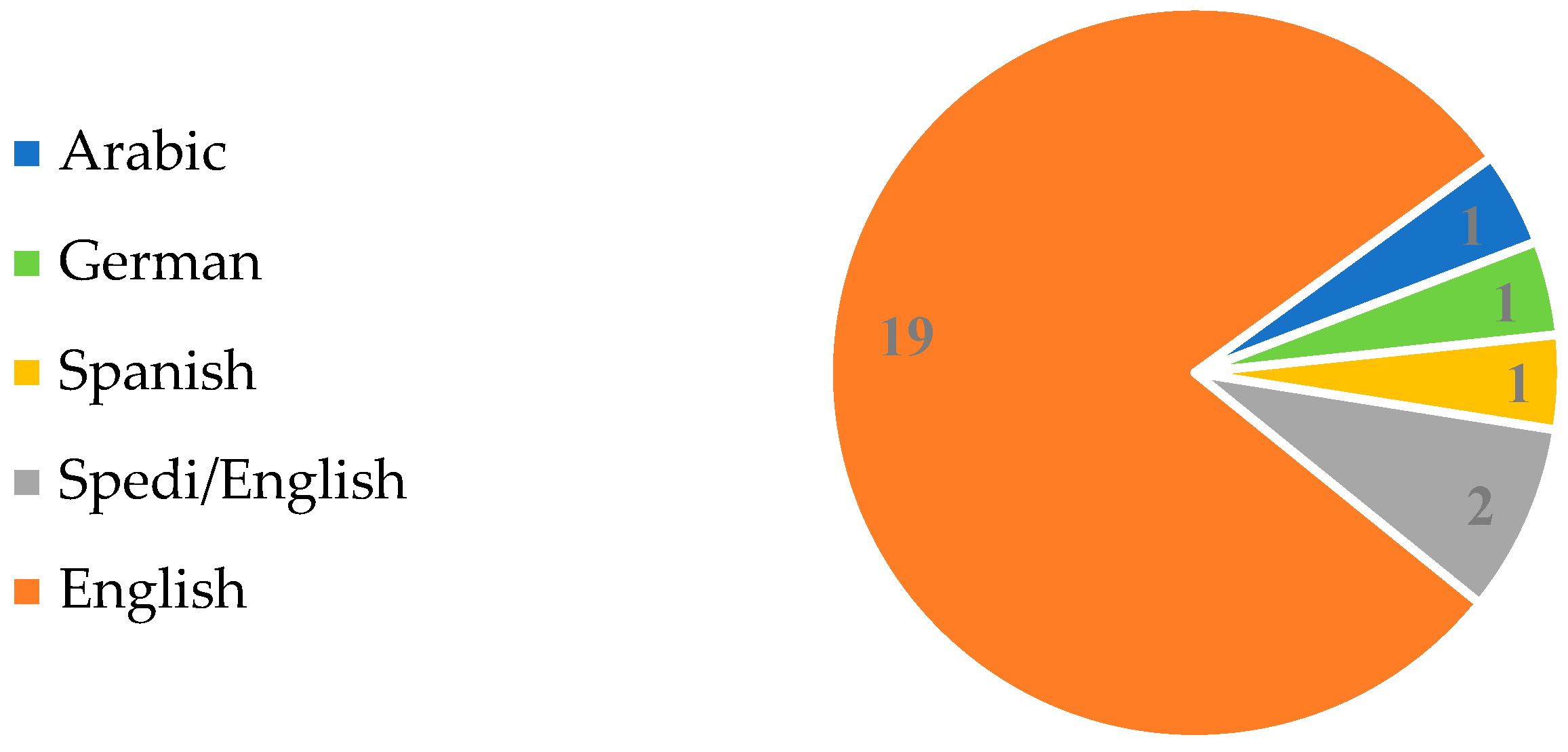

| First Language/s | |||

| Target language/s | |||

| Sample | |||

| Number of groups | Power analysis | N/groups | Comparison |

| Instrument type—quantitative | |||

| Data collection—qualitative | |||

| Trans-application | |||

| Analysis | |||

| Assumption checks | Reliability | Coding details | Coder reliability |

| Result Reporting | |||

| Quantitative | M (SD) | t, f, p, etc., values | Effect size |

| Qualitative | Triangulation | Transparency |

| Database | Search Results | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Academic Search Ultimate | 58 |

| 2 | Education Full Text | 22 |

| 3 | ERIC | 77 |

| 4 | Google Scholar | 31 |

| 5 | JSTOR | 329 |

| 6 | Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts (LLBA) | 5 |

| 7 | ProQuest | 292 |

| 8 | PsycINFO | 44 |

| 9 | Scopus | 74 |

| 10 | Social Science Database | 87 |

| 11 | Web of Sciences | 164 |

| Total | 1183 |

| Year | N | Articles | Dissert. | Conf. Proc. | K | Qual. | Quant. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1974-22 | 21 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 9 | 16 |

| Study ID | Context | Location | TransL | TL | Sample Size | Edu. Level | Design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Studies | ||||||||

| Carroll and Sambolín Morales (2016) | SL | Puerto Rico | Spanish | English | 29 | Tertiary | Case Study—Descriptive | Favor |

| Caruso (2018) | ML | Portugal | Multiple Ls | English | 15 | Tertiary | Case Study—Intervention | Favor |

| Ceprano et al. (2018) | FL | Italy | Italian | English | 22 | Elementary | Case Study—Descriptive | Favor |

| Hopewell (2013) | SL | U.S. | Spanish/English | English | 49 | Tertiary | Qualitative (Reflective Practitioner Research) | Favor |

| Hungwe (2019) | ML | S. Africa | Multiple Ls | English | 36 | Tertiary | Case Study—Intervention | Favor |

| Martin-Beltrán et al. (2019) | SL | US | Spanish | English | 9 | Elementary | Mixed Methods—Action Research | Favor |

| Martínez-Roldán and Sayer (2006) | SL | US | Spanish/English | English | 8 | Elementary | Ethnographic—Classroom Study | Favor |

| Mbirimi-Hungwe (2016) | FL | S. Africa | Multiple Ls | English | 181 | Tertiary | Qualitative Intervention | Favor |

| Yang et al. (2021) | SL | US | Chinese | English | 1 | Elementary | Case Study—Descriptive | Favor |

| Quantitative Studies | ||||||||

| Abdulaal (2020) | FL | Egypt | Arabic | English | 63 | Tertiary | RCT (pretest–posttest) | Favor |

| Bin-Tahir et al. (2018) | FL | Indonesia | Not provided | Arabic | 64 | Tertiary | Quasi-Experimental (pretest–posttest) | Favor |

| Cohen (1974) | IM | U.S. | English/Spanish | English | 30 | Elementary | Quasi-Experimental (pre/post longitudinal) | No Difference |

| Cohen (1974) | IM | U.S. | English/Spanish | Spanish | 21 | Elementary | ---- | No Difference |

| Chu (2017) | FL | Taiwan | Chinese | English | 123 | Secondary | Quasi-Experimental (posttest-only) | Favor |

| Iranmanesh and Golshan (2018) | FL | Iran | Persian | English | 46 | Tertiary | Quasi-Experimental (pretest–posttest) | Favor |

| Ledwaba (2020) | SL | S. Africa | English/Sepedi | English/Sepedi | 70 | Elementary | Quasi-Experimental (pretest–posttest) | Favor |

| Makalela (2015) | SL | S. Africa | Sepedi/English | Sepedi/English | 60 | Secondary | Quasi-Experimental (pretest–posttest) | Favor |

| Makalela (2015) | SL | S. Africa | Sepedi/English | Sepedi/English | 60 | Secondary | ---- | Favor |

| Nur et al. (2020) | FL | Indonesia | Not provided | English | 35 | Secondary | Quasi-Experimental (pretest–posttest) | No Difference |

| Qureshi and Aljanadbah (2022) | FL | UAE | Arabic | English | 65 | Tertiary | Quasi-Experimental (pretest–posttest) | No Difference |

| Roussel et al. (2017) | FL | France | French | German | 102 | Tertiary | RCT (pretest–posttest) | Favor |

| Roussel et al. (2017) | FL | France | French | English | 84 | Tertiary | ---- | Favor |

| Roussel et al. (2017) | FL | France | French | English | 108 | Tertiary | ---- | No Difference |

| Sefotho and Makalela (2017) | ML | S. Africa | ML | English | 60 | Elementary | Quasi-Experimental (pretest–posttest) | No Difference |

| Yafele (2021) | FL | S. Africa | ML | English | 25 | Tertiary | Quasi-Experimental (pretest–posttest) | Favor |

| Study | Outcome as Reported in the Samples | Hedge’s g | CI Lower | CI Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdulaal (2020) | Yes | 0.31 | 2.80 | 4.40 |  |

| Bin-Tahir et al. (2018) | Yes | 2.61 | 1.94 | 3.28 | |

| Cohen (1974), 1 * | No | 0.23 | −0.43 | 0.90 | |

| Cohen (1974), 2 | No | 0.13 | −0.53 | 0.80 | |

| Chu (2017) | Yes | 1.15 | 0.76 | 1.53 | |

| Iranmanesh and Golshan (2018) | Yes | −0.63 | −1.23 | −0.04 | |

| Ledwaba (2020) | Yes | −0.75 | −1.23 | −0.26 | |

| Nur et al. (2020) | No | 0.72 | 0.03 | 1.40 | |

| Qureshi and Aljanadbah (2022) | No | 0.05 | −0.44 | 0.54 | |

| Roussel et al. (2017), 1 * | Yes | 1.22 | 0.09 | 1.54 | |

| Roussel et al. (2017), 2 | Yes | 1.13 | 0.78 | 1.48 | |

| Roussel et al. (2017), 3 | No | 0.92 | 0.63 | 1.22 | |

| Sefotho and Makalela (2017) | No | 0.30 | −0.21 | 0.81 | |

| Makalela (2015), 1 * | Yes | −2.50 | −2.98 | −2.02 | |

| Makalela (2015), 2 | Yes | −1.82 | −2.25 | −1.39 | |

| Overall weighted effect size | 6/10 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.45 | |

| Yafele (2021) | Yes | -- | -- | -- |

| Study ID | TL Application | Duration | Depth/Triangulation | Transparency | Coding Details | Coder Reliability | Inter-Rater Reliability | Other Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carroll and Sambolín Morales (2016) | Literacy circles | 1 month | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

|

| Caruso (2018) | Any L in discussion; presentation in 3 Ls | 17 h | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| Ceprano et al. (2018) | Bilingual read-aloud and guided readings | 10 days | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| Hopewell (2013) | Literacy circles | 4 sessions | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

|

| Hungwe (2019) | Discuss text: any L Half-class paraphrase: English Half in home language | 1 session | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| Martin-Beltrán et al. (2019) | Buddies discussed Qs with younger buddies: L1 | 15 sessions, 45 min | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

|

| Martínez-Roldán and Sayer (2006) | 24 retelling sessions in alternate languages 40 min each 1-week observation 2 discussion sessions | 1 semester | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

|

| Mbirimi-Hungwe (2016) | TL: Read/discuss: any L CG: Read/discuss: English | 1 session | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| Yang et al. (2021) | Bilingual use reading story books at home | 3 months | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

|

| 8 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Explanation/answers to students’ queries in L1 | Reading text in one language—answering in another |

| Sight words in L1 | Text glossed in L1 |

| Discussion in L1/L2 | Summarizing in L1/L2 or any language |

| Retelling a story in L1/L2 | Multilingual explanations |

| Matching keywords in L1 with those in L2 | Note-taking/annotations in any language |

| Reading a story in two languages | Brainstorming/outlining in any language |

| Alternation of languages in vocabulary, silent reading, and reading aloud exercises | Translingual collaboration |

| Print environment in two languages | Using multilingual dictionaries and Google Translate |

| Study ID | TL Application | Duration | A Priori Sample | Comparison Group | Coding/Scoring | Reliability Check | Assumption Check | Statistical Analysis | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdulaal (2020) | Pre-reading in L1 | 4 weeks | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Kruskal–Wallis |

|

| Bin-Tahir et al. (2018) | Not provided | Not stated | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | t-test |

|

| Cohen (1974), 1 | Simultaneous bilingual instruction | 1 year | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not reported |

|

| Cohen (1974), 2 | ---- | 1 year | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | RM-ANOVA |

|

| Chu (2017) | Qs in L1 Chinese | 1 session | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | t-test correlations |

|

| Iranmanesh and Golshan (2018) | Explanation/answer to queries in L1 | 1 semester | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | t-test |

|

| Ledwaba (2020) | Sight words—L1 Discussion—L1/L2 Retelling story—L1/L2 Matching L1 words with L2 | 30 min | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | t-test |

|

| Makalela (2015), 1 | A story and activities in 2 Ls Print environment in 2 Ls Reading text in 1 L and answers in another | 1 session | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | t-test |

|

| Makalela (2015), 2 | ---- | 1 session | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | t-test |

|

| Nur et al. (2020) | Text and MCQs: English and Indonesian | Not stated | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | t-test |

|

| Qureshi and Aljanadbah (2022) | Text glosses in L1 Discussion in L1/L2 Summary in L1/L2 | 1 session | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | t-test |

|

| Roussel et al. (2017), 1 | Reading in L1 Reading in L2 Reading in L2 with L1 translation | 15 min | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ANOVA |

|

| Roussel et al. (2017), 2 | ---- | 15 min | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ANOVA |

|

| Roussel et al. (2017), 3 | ---- | 15 min | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ANOVA |

|

| Sefotho and Makalela (2017) | Not provided | Not stated | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | t-test |

|

| Yafele (2021) | Reading activities in any L Translingual collaboration Multilingual dictionaries and Google Translate | 1 session | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | t-test |

|

| 1 | 14 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qureshi, M.A.; Al-Surmi, M. Translanguaging and Second-Language Reading Proficiency: A Systematic Review of Effects and Methodological Rigor. Languages 2025, 10, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080200

Qureshi MA, Al-Surmi M. Translanguaging and Second-Language Reading Proficiency: A Systematic Review of Effects and Methodological Rigor. Languages. 2025; 10(8):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080200

Chicago/Turabian StyleQureshi, Muhammad Asif, and Mansoor Al-Surmi. 2025. "Translanguaging and Second-Language Reading Proficiency: A Systematic Review of Effects and Methodological Rigor" Languages 10, no. 8: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080200

APA StyleQureshi, M. A., & Al-Surmi, M. (2025). Translanguaging and Second-Language Reading Proficiency: A Systematic Review of Effects and Methodological Rigor. Languages, 10(8), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080200