1. Introduction

Experience with language use is widely recognised as fundamental to the process of language acquisition (

Ambridge et al., 2015b;

Behrens, 2006;

Goldberg, 2019;

Tomasello, 2003). Research in the field of second language (L2) acquisition has demonstrated that L2 input—whether estimated indirectly via a first language (L1) proxy (

Ellis & Ferreira-Junior, 2009;

Kyle & Crossley, 2017) or directly measured through materials employed in L2 instructional settings (

Alsaif & Milton, 2012;

Jung et al., n.d.;

Lee et al., 2024)—plays an important role in shaping the trajectory by which L2 learners attain target-like competence (

Ellis, 2002;

Madlener, 2015). Concurrently, L2 learners frequently encounter between-language competition during L2 activities (

Hartsuiker et al., 2004;

Jiang et al., 2011;

MacWhinney, 2008), a challenge that is compounded by an increased cognitive load (

Cunnings, 2017;

Jacob & Felser, 2016;

Pozzan & Trueswell, 2016). This interplay often results in a reduced ability to effectively utilise acquired target knowledge during L2 tasks (

Futrell & Gibson, 2017;

Robenalt & Goldberg, 2016;

Tachihara & Goldberg, 2020), thereby modulating the influence of usage experience on the acquisition of target language systems.

The present study investigates how varying usage experience, induced by language-learning environments, impacts learning outcomes in the context of Korean as a non-dominant language. Korean is an agglutinative language with a Subject–Object–Verb word order, characterised by the active use of particles and verbal morphology to convey grammatical information. Moreover, its situational orientation and context dependency permit the omission of essential linguistic elements when such omissions can be readily inferred from the context (

Sohn, 1999). Despite the growing global interest in Korean culture and language, research in the field of language acquisition has predominantly focused on a limited number of major languages (

Kidd & Garcia, 2022;

Nielsen et al., 2017), with the L2 acquisition literature particularly skewed towards English as the target language.

In this study, we examine two distinctive cohorts of L2-Korean learners who share English as their dominant language yet exhibit markedly different language learning profiles. The first group comprises L2 learners situated in foreign language contexts, where acquisition is primarily supported through structured, formal classroom instruction. Prior studies on the acquisition of clausal constructions in L2 Korean have consistently highlighted the individual and interactive roles of morphosyntactic cues and cross-linguistic influence in the comprehension and processing of these constructions (

Frenck-Mestre et al., 2019;

Hwang et al., 2018;

Lee et al., 2024;

Park & Kim, 2022,

2023).

Kim (

2025) elucidates how the scrambling of sentential elements in Korean, together with cue conflicts arising from typological differences between L1 and L2, jointly affects learners’ processing of agreement relations involving honorific numerical quantifiers. The results indicate that, while both L1-Chinese and L1-Japanese learners are capable of employing language-common, language-contrasting, and language-specific cues during sentence processing, the efficacy of utilising these cues is contingent upon the status of the target knowledge shared across languages and the competition between that knowledge and the corresponding L1 knowledge. Through acceptability judgement and self-paced reading tasks conducted with L2-Korean learners from English, Czech, and Japanese backgrounds,

Shin and Shin (

n.d.) further demonstrate that typological similarity alone does not guarantee the successful processing of Korean dative constructions. Rather, factors such as usage frequency, form–function mapping of case particles, and task requirements substantially influence L2 sentence processing behaviours, highlighting the complex and noisy nature of L2 knowledge.

The other group in this study consists of heritage language speakers—children and adults belonging to a linguistic minority whose home language exposure and formal literacy education are relatively limited, while the majority language in their community remains dominant (

Montrul, 2010;

Rothman, 2009). These populations tend to exhibit asymmetrical linguistic representations, influenced by factors such as reduced home-language input, the predominance of the majority language, the inherent grammatical properties of specific target items, and available cognitive resources (

Felser & Arslan, 2019;

Jia & Paradis, 2015;

Kondo-Brown, 2005;

Mikhaylova, 2018;

O’Grady et al., 2011; for an in-depth overview, see

Polinsky & Scontras, 2020). Previous research has revealed distinctive aspects of heritage speakers’ morphosyntactic knowledge when compared to that of L1 or L2 speakers (

Fuchs, 2022;

Kim et al., 2009;

Laleko & Polinsky, 2016;

Montrul et al., 2019). Our study specifically targets Korean heritage language speakers residing in the United States. With over 1.9 million individuals using Korean as a heritage or community language, this group represents the fifth largest Asian American subgroup (

U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Nonetheless, research within the US context has largely concentrated on dominant heritage language groups such as Hispanics or Chinese (

Bice & Kroll, 2021;

Hur et al., 2020;

Jegerski, 2018;

López Otero et al., 2023;

Scontras et al., 2017;

Torres, 2023), thereby underscoring the pressing need for focused scholarly attention on this population.

Taking these considerations into account, our focus shifts to examining the comprehension behaviour of subject–predicate honorific agreement in Korean among the two groups. As will be detailed in

Section 2, this knowledge embodies both cross-linguistic consistency (i.e., an agreement relation at the morphosyntactic level) and language-specific properties (i.e., the context-driven optionality) inherent in its use. This duality offers an intriguing testing ground for the core inquiry in the present study.

2. Subject−Predicate Honorific Agreement in Korean

Honorification represents a distinctive feature of Korean, which necessitates a blend of phonological, morphosyntactic, and semantic−pragmatic knowledge for its appropriate use (

Brown, 2015;

Sohn, 1999), thereby serving as a cornerstone of communicative competence. Our focus centres on the morphosyntactic dimensions of subject–predicate honorific agreement, with particular attention to the honorific verbal suffix-

(u)si (-

usi following a consonant), which is amongst the most captivating elements in this regard. This suffix exhibits a systematic dependency between a grammatical subject and its corresponding predicate (

Kwon & Sturt, 2016;

Sohn, 1999). Specifically, it attaches to a predicate stem to signal its connection with an honorifiable subject, such as in the case of

sensayngnim ‘teacher,’ as in (1). Importantly, this suffix is not used with subjects that lack the capacity for honorification, as exemplified in (2).

| (1) Subject−predicate honorific agreement: Correct usage. |

| sensayngnim-kkeyse | pang-ulo | tuleka-si-ess-ta. |

| teacher-NOM.HON | room-DIR | go.into-HON-PST-DC1 |

| ‘The teacher went into the room.’ |

| (2) Subject−predicate honorific agreement: Incorrect usage |

| *ai-ka | pang-ulo | tuleka-si-ess-ta. |

| *child-NOM | room-DIR | go.into-HON-PST-DC |

| ‘The child went into the room.’ |

A further notable attribute of Korean subject–predicate honorific agreement is its gradient nature. The use of

-(u)si can be rendered optional in contexts where the formality or hierarchical distinctions between interlocutors are relaxed, or where the relationship between the speaker and addressee is sufficiently close. This optionality may result in a non-honorific predicate accompanying an honorifiable subject, as in (3). Although this combination might be considered infelicitous in strict grammaticality, it is deemed acceptable in colloquial speech and can serve to convey subtle discourse effects, such as the speaker’s sense of intimacy with the entity being referenced (

Sohn, 1999).

| (3) Subject−predicate honorific agreement: Honorifiable subject + no honorific suffix. |

| emma-ka | pang-ulo | tuleka-ss-ta. |

| mother-NOM | room-DIR | go.into-PST-DC |

| ‘(My) mother went into the room in haste.’ |

We delineate four conditions related to the honorifiability of a subject and the corresponding realisation of the honorific verbal suffix, as illustrated in

Table 1.

Some experimental studies have investigated native speakers’ behaviour concerning this knowledge (

Kwon & Sturt, 2016;

Song et al., 2019).

Song et al. (

2019), amongst others, conducted both an acceptability judgement task (employing a five-point Likert scale) and a grammaticality judgement task (offering binary yes/no responses) with 384 adult speakers using the four condition types described above. Their results indicated that speakers generally accepted condition (b) while rejecting condition (c). A subsequent corpus analysis further demonstrated a high probability of using an honorifically marked subject when the predicate was also marked; however, the reverse pattern was not observed. These findings substantiate that condition (b) is indeed acceptable and not categorically ungrammatical.

Several studies in L2-Korean research have addressed issues of acquisition concerning this knowledge.

Brown (

2010) examined how dialogues from three textbook types—ranging from novice to advanced levels—present Korean honorification system overall. The study identified three main trends regarding subject honorification. First, the initial presentation of

-(u)si in the textbooks was exclusively through the verbal form

-(u)seyyo (i.e.,

-(u)si combined with

-e/ayo) used for imperatives and second-person interrogatives, without explicit explanation of this combination. Second, the token frequency of

-(u)si increased from the novice to intermediate stages, only to decline from intermediate to advanced levels in two of the textbooks. Third, it was found that in over 60% of dialogues—typically between casual acquaintances—honorification was applied without appropriate contextual modification. These findings imply that the introduction of

-(u)si was somewhat sporadic and lacked a systematic progression within these textbooks. Further analysis by

Jung et al. (

n.d.) revealed two critical aspects in L2 textbook design: an overemphasis on honorification (and particularly on the use of the honorific verbal suffix as a means of honorification) and an insufficient provision of contexts that would encourage learners to develop proper usage of this feature.

Mueller and Jiang (

2013) explored the sensitivity of advanced L1-English L2-Korean learners to the grammaticality of this agreement relation using a self-paced reading task that incorporated the same conditional distinctions mentioned earlier. Through pairwise comparisons between the four conditions ([a] vs. [b] and [c] vs. [d]), they observed no significant differences in reading times, leading them to claim that even advanced learners—who demonstrated explicit knowledge of

-(u)si through a written test they developed—showed no sensitivity to the error in condition (c) or to the infelicity in condition (b). However, caution is warranted in accepting their conclusions due to methodological limitations. For example, the test sentences were structurally complex, featuring two subjects at the sentence onset, a relative clause in the middle, and three additional segments following an embedded clause. Such complexity complicates the determination of whether the learners’ performance was due to an incomplete maturation of the target knowledge or simply the processing demands imposed by the intricate sentence structure. Additionally, the reliability and validity of the offline fill-in-the-blank test they developed were not rigorously confirmed, leaving uncertainty as to whether it accurately measured the intended linguistic knowledge.

3. Methods

Research on the acquisition of subject–predicate honorific agreement in Korean as a second or non-dominant language remains both limited and unsystematic. To date, no study has investigated how learners manage the notable mismatch between the honorific features of the subject and predicate in response to specific language-use environments. The present study addresses this gap by employing an acceptability judgement task in conjunction with reaction time measurement. In an acceptability judgement task, a reader examines a sentence both partially and holistically within relatively brief time constraints before arriving at a final interpretation and deciding on its acceptability. It is important to note that the outcome of this task does not necessarily confirm that the reader has attained target-like linguistic knowledge, as acceptability reflects a perceptual response to linguistic stimuli (

Bresnan, 2007;

Schütze, 1996;

Sprouse & Almeida, 2013). Nonetheless, extensive research has effectively used this methodology to reveal a reader’s offline knowledge of the target phenomenon (

Ambridge et al., 2015a;

Bidgood et al., 2014;

Dąbrowska, 2010;

Robenalt & Goldberg, 2016;

Tachihara & Goldberg, 2020). Reaction time adopted in this study is defined as the interval between encountering a sentence and making a final decision regarding its acceptability, irrespective of whether the decision is correct. This measure serves as an index of processing complexity (

Schütze & Sprouse, 2014) and acts as a proxy for the recruitment and utilisation of cognitive resources during the task, often reflecting the efficiency and automatism with which target knowledge is processed (

Grodner & Gibson, 2005;

Kharkwal & Stromswold, 2014;

Shapiro et al., 2003).

3.1. Participants

We recruited 24 L1-English L2-Korean learners (USA; age: M = 23.8, SD = 4.3) and 40 Korean heritage language speakers (KHS; age: M = 24.0, SD = 5.2), all of whom were undergraduate students residing in the United States. In addition, 40 native speakers of Korean (NSK; age: M = 23.6, SD = 4.1) were recruited as a control group.

The USA group had studied Korean as a foreign language for approximately four years (M = 4.4 years, SD = 2.0) and had spent less than three months staying in Korea (M = 2.1 months, SD = 2.3) at the time of testing. Their primary exposure to Korean was through university courses and textbooks, although many also supplemented their learning with online resources, including YouTube clips, language-learning apps, and various K-culture products.

The KHS group, on the other hand, were born in the United States and raised in Korean-speaking households, having lived in America for the majority of their lives (length of stay in the USA: M = 21.9, SD = 6.2). They predominantly used English in their daily interactions (English: M = 92.5, SD = 9.5; Korean: M = 37.1, SD = 27.3; score out of 100), and their use of Korean was more frequent in family contexts than with colleagues (family: M = 4.98, SD = 1.25; friends: M = 3.45, SD = 1.38; colleagues: M = 3.25, SD = 1.63; scores were on a six-point scale where 1 indicates ‘English only’ and 6 indicates ‘Korean only’). They reported higher confidence in their listening and speaking abilities in Korean (M = 4.03, SD = 0.92 [0 = not good; 5 = very good]) compared to their reading and writing skills (M = 3.05, SD = 1.20 [0 = not good; 5 = very good]), a difference that was statistically significant as confirmed by a one-sample t-test: t(78) = 4.085, p < 0.001. Despite this, they were somewhat unsatisfied with their spoken Korean (M = 2.83, SD = 1.39 [0 = not satisfied; 5 = very satisfied]) and perceived their overall command of Korean as falling short of target-like use (M = 2.05, SD = 1.66 [0 = fully disagree; 5 = fully agree]). All KHS participants primarily acquired Korean from their parents, with supplementary exposure provided through educational institutions such as language schools, universities, and academies (80%), online resources (70%), and social interactions with friends and peers (70%).

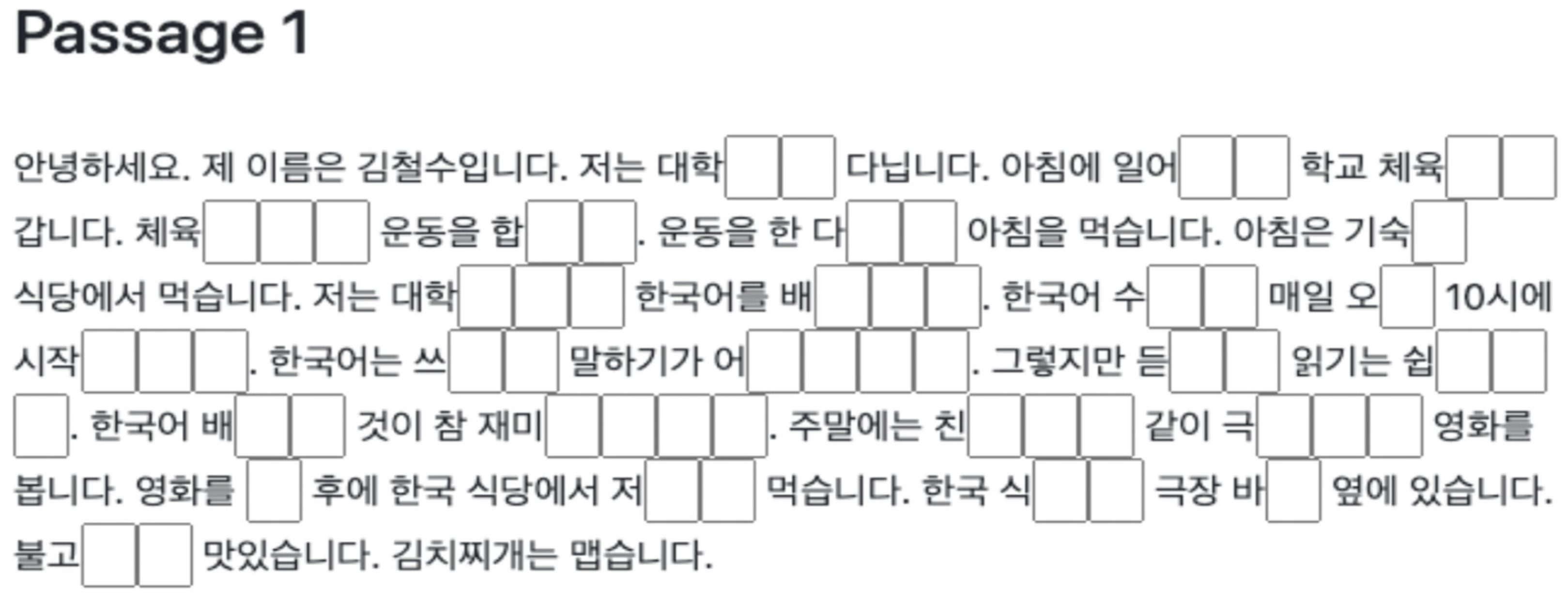

Proficiency in Korean was evaluated using the Korean C-test (

Lee-Ellis, 2009), which assesses the comprehension of Korean sentences of varying lengths and complexities. The test comprises five passages in which blanks are inserted at the syllable level. As illustrated in

Figure 1, each blank represents a syllable from either a content or function word and may occur in various positions within an

eojeol (the minimal language unit in Korean, defined by white-space segmentation). For efficiency, we administered only the first four passages, following the recommendations of the original study. Each correctly filled blank was awarded 1 point, with a maximum possible score of 188. Completion of the test required approximately 20 min.

The main task, acceptability judgement, required a minimum level of reading proficiency. However, the C-test utilised in the current study does not provide standard proficiency indications such as those found in CEFR. Consequently, following the rationale established by

Lee et al. (

2024), we set a threshold score of 63 out of 188 (approximately 33%) to classify participants as having sufficient proficiency in Korean. Applying this criterion led to the exclusion of six participants from the initial cohort of the USA group—30 participants, resulting in a final sample of 24. We hope that future studies with larger and more balanced samples would replicate the findings reported in our study.

3.2. Materials

We constructed a total of 128 test sentences (32 items * 4 conditions as specified in

Table 1; see

Supplement Material for a complete list). In each test sentence, we employed simple, common, and frequently occurring nouns for the subjects (such as kinship terms, personal names, and occupations) and paired these with adjectives or verbs for the predicates. Notably, there was no repetition of subjects or predicates across the sentences. Prior to the main experiment, we normed these sentences by having an additional 10 native Korean speakers evaluate their grammaticality and ungrammaticality, in accordance with our intended design. To obscure the true purpose of the experiment, we also incorporated 256 filler sentences that varied in both complexity and grammaticality. The test sentences and fillers were divided into four sub-lists, which were then randomly allocated to participants, with the order of sentence presentation within each sub-list being fully randomised.

3.3. Procedure and Analysis

We conducted an acceptability judgement task using Qualtrics. Each participant joined a Zoom meeting individually and was instructed to rate the acceptability of each sentence on a 6-point Likert scale (with 0 indicating ‘very unacceptable’ and 5 indicating ‘very acceptable’). Participants were advised to respond as quickly as possible while maintaining accuracy and confidence in their evaluations. Once a numeric value was selected and the participant proceeded to the subsequent sentence, they were not able to revisit or modify their previous responses. In addition, we recorded the reaction time—the duration from when a sentence appeared on the screen until the participant made their final decision (as measured by the time taken to register a click on one of the scale points)—as an index of processing cost. To ensure a stable testing environment, the use of mobile devices was not permitted. Participants were allowed to complete the task in any location of their choosing (e.g., at home or on campus), provided they had a reliable internet connection and were able to remain undisturbed throughout the session. For this reason, we requested that all participants (i) check their internet connection and ensure that their surroundings were free of distractions prior to starting the task, and (ii) remain in the meeting room until the entire session was completed, thereby enabling us to monitor their participation in real time. Overall, the task required approximately 20 min to complete.

Data from both measures were initially refined by excluding responses with reaction times below 1000 ms or above 10,000 ms (resulting in a data loss of 10.93%). The remaining, trimmed data were then used for the planned analyses. For the acceptability judgement data, ordinal regression modelling was employed using the cumulative link mixed model function from the ordinal package (

Christensen, 2023) in

R (

R Core Team, 2024). To more accurately assess group differences, pairwise comparisons were conducted (NSK–USA, NSK–KHS, USA–KHS), focusing exclusively on conditions (b, infelicitous) and (c, ungrammatical). Each model included two fixed effects—Group (NSK vs. USA; NSK vs. KHS; USA vs. KHS) and Condition (b vs. c)—as well as their interaction. Both fixed effects were centred around the mean and were deviation-coded. All models included the maximal random-effects structure permitted by the design (cf.

Barr et al., 2013). Given the ordinal nature of the outcome variable, a logit link function was applied to model the cumulative probability of higher ratings. Model fitting and validation involved checks for convergence, the verification of the proportional odds assumption, and residual diagnostics. An effect size for each model was computed by approximating Nagelkerke’s

R2, using comparisons of the log-likelihoods between the final model and a null model which contained only an intercept for the fixed effects and the full random-effects structure. Pairwise post hoc comparisons were performed using the emmeans package (

Lenth, 2025), with

p-values derived from Wald

z-tests as implemented in the ordinal package.

For the reaction time data, the trimmed values were log-transformed to achieve normality and subsequently fitted to linear mixed-effects models using the lme4 package (

Bates et al., 2015). Each model’s

R2 was computed using Nakagawa’s

R2 (

Nakagawa & Schielzeth, 2013), which considers both fixed and random effects (conditional

R2). All other specifications mirrored those used in the acceptability judgement data.

5. General Discussion

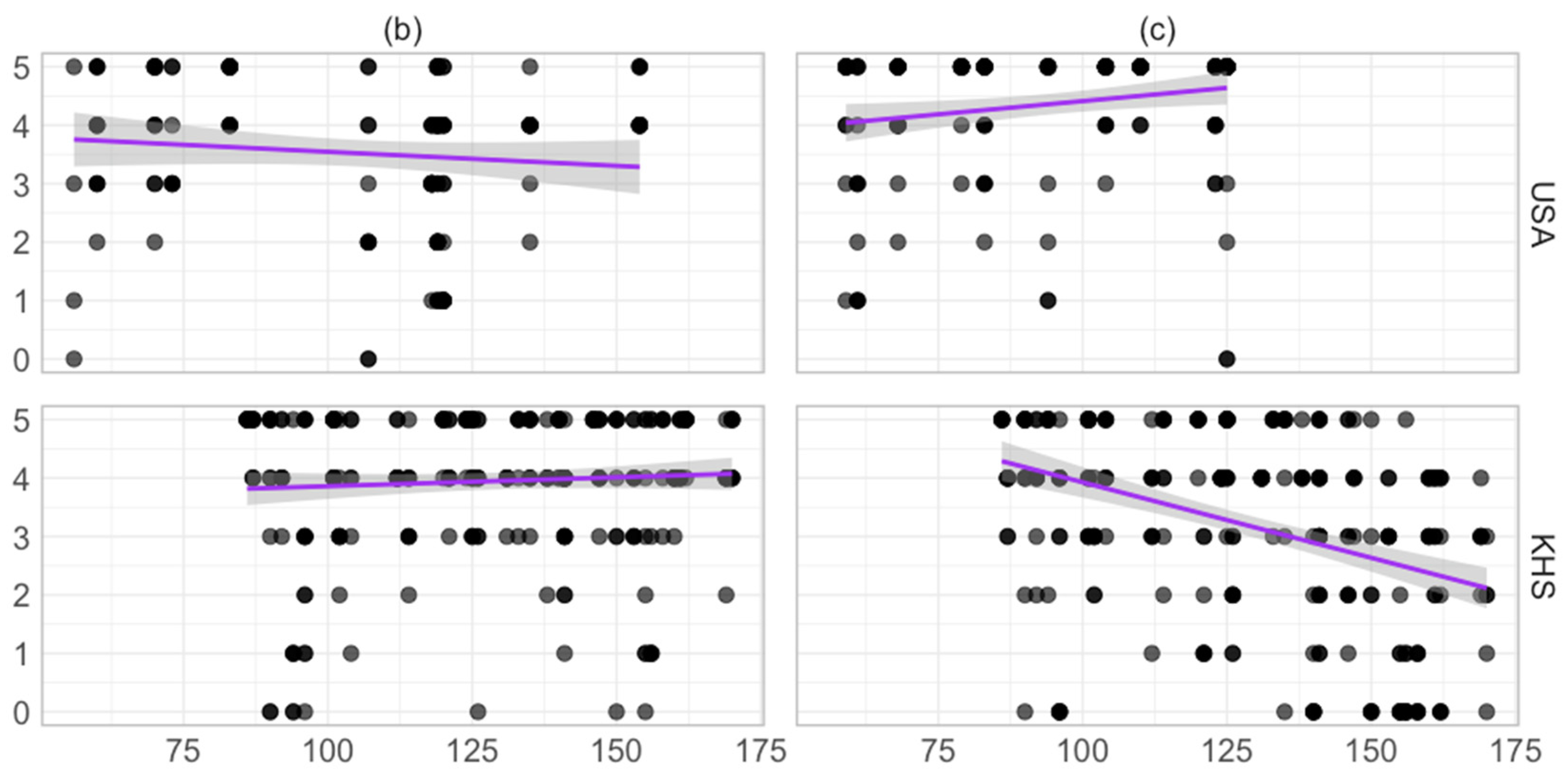

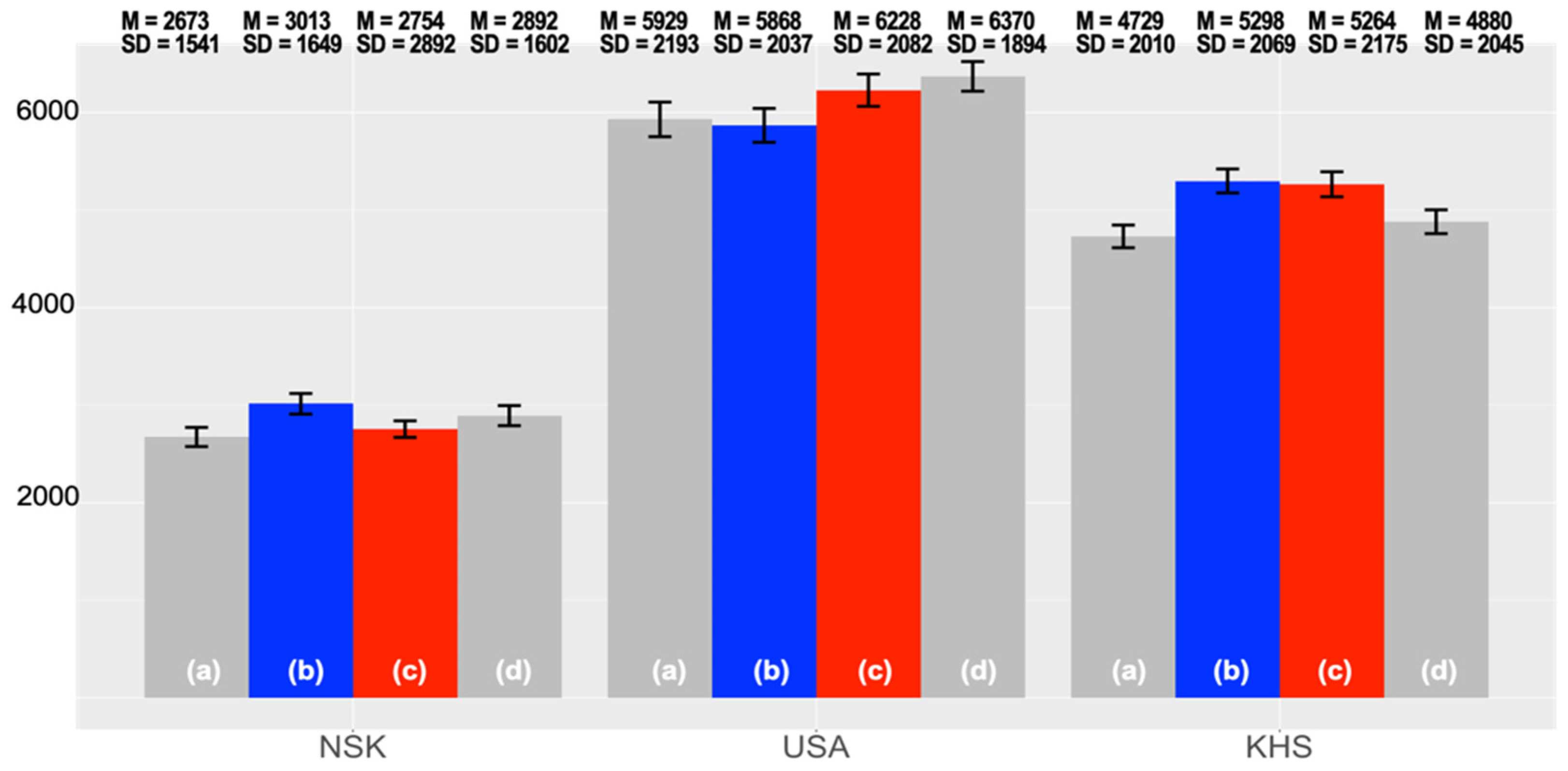

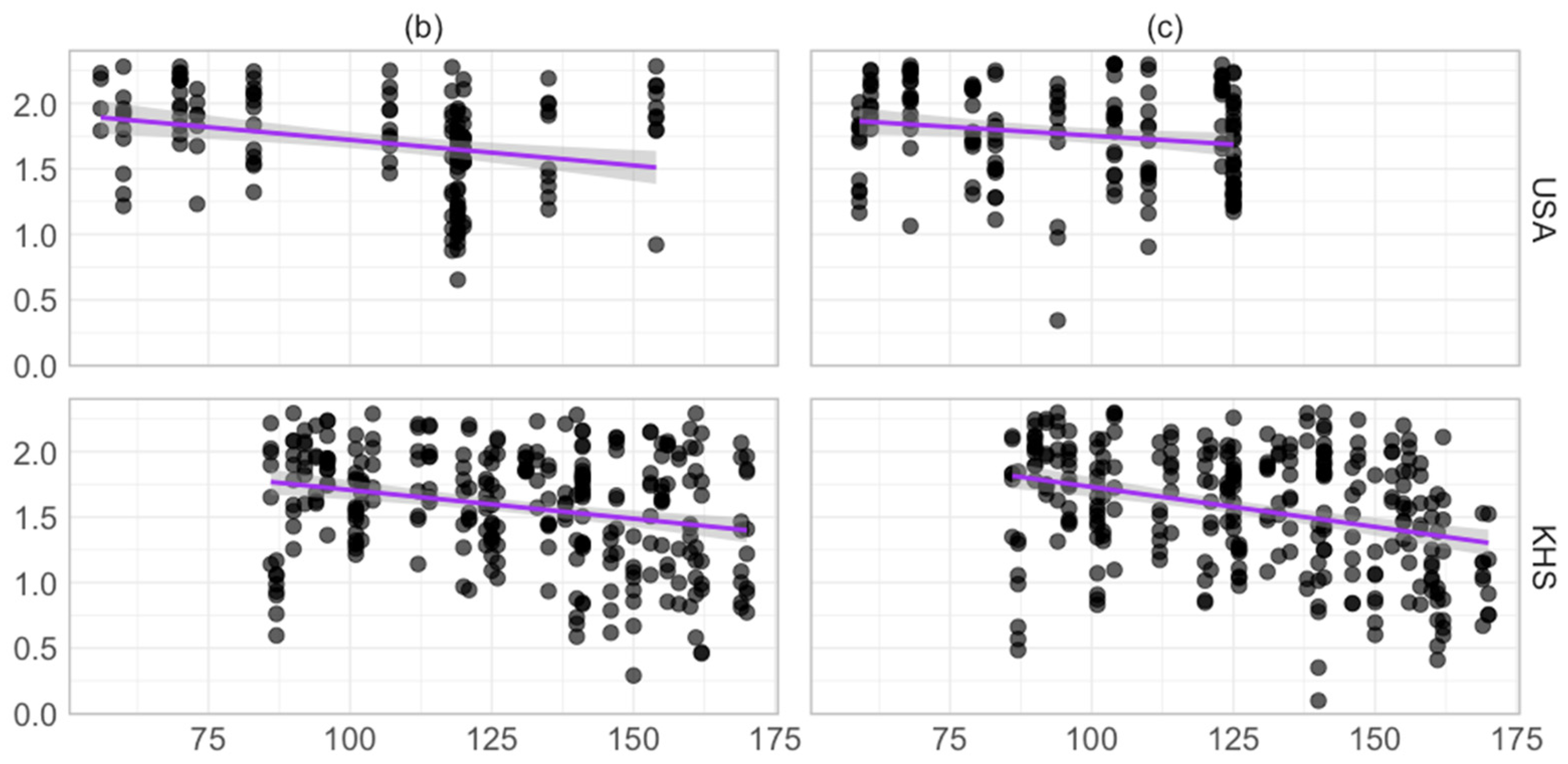

The two learner groups—English-speaking learners of Korean and heritage language speakers of Korean—demonstrated notable difference in performance when rating sentences involving subject–predicate honorific agreement. In the acceptability judgement task, although both groups rated the infelicitous condition (b) similarly, the heritage speaker group evaluated the ungrammatical condition (c) to be substantially less acceptable than did the English-speaking learner group. General proficiency in Korean modulated the evaluations of condition (c) in opposite directions between the two groups. Regarding reaction time, both learner groups spent considerably more time to assess acceptability than the native speaker group, which is consistent with previous studies indicating that non-dominant language or L2 users face global challenges in online sentence processing (

Grüter & Rohde, 2021;

Hopp, 2014;

McDonald, 2006). Notably, the heritage speaker group responded significantly faster for both conditions (b) and (c) when compared to the English-speaking learner group. A higher proficiency in Korean was correlated with faster reaction times in both groups.

The USA group’s comprehension behaviour appeared to result from the combined influence of their exposure to specific linguistic environments and the linguistic properties of their L1. For example, this group’s leniency towards the ungrammatical condition (c) seemed to derive from two primary factors. One is the nature of L2 textbooks, which tend to over-emphasise honorification, particularly through the heavy reliance on the honorific verbal suffix. Research has shown that the characteristics of L2 input—as typified by textbook materials—contribute significantly to shaping the broad framework of L2 knowledge (

Alsaif & Milton, 2012;

Lee et al., 2024). Consequently, this may have led the USA group in the current study to be more generous in their ratings of sentences featuring the overt honorific verbal suffix, irrespective of the actual agreement relation.

The second factor is related to the morphosyntactic properties of English, the L1 of the USA group. As an analytic language with a relatively weak inflection and agreement system compared to agglutinative or (poly)synthetic languages, English may predispose learners to certain processing challenges. Given that the L2 mind is often heavily taxed during language activities (

Cunnings, 2017;

Pozzan & Trueswell, 2016), the USA group in the current study may have occasionally been less attentive to accurately computing the agreement relation between the subject and predicate, particularly under the strong influence of L2 textbook input. Supporting this interpretation,

Jung et al. (

n.d.) provided independent evidence by comparing English-speaking and Czech-speaking learners of Korean using the same experimental paradigm. They found that L1-Czech L2-Korean learners demonstrated greater stringency when rating the ungrammatical condition (c) than their English-speaking counterparts, despite similar reaction times. This suggests that the more robust agreement system in Czech may enable learners to better discern the appropriateness of the honorific verbal suffix.

2 In this respect, the USA group in our experiment may have experienced difficulty in consistently and reliably handling the honorific verbal suffix when assessing the agreement relation.

3The KHS group’s acceptability ratings for the ungrammatical condition (c) were significantly higher than those of the NSK group, albeit not as high as those observed for the USA group. Furthermore, the KHS group spent considerably less time than the USA group to evaluate the acceptability of test sentences in this condition (and across all conditions). These findings suggest that the KHS group’s performance may be attributed to their enhanced capacity for engaging in home language activities in two distinct ways. First, it is plausible that the KHS group mitigated the influence of L2 textbook input regarding honorification to some extent, enabling them to more closely approximate target-like interpretations of sentences involving the agreement relation, as evidenced by their acceptability ratings. Second, the processing load associated with their home language may have been somewhat alleviated during the sentence evaluation process, thereby allowing them to perform the requisite computations more efficiently than the USA group, as reflected in their reaction times. We contend that these two aspects are engendered by the extensive use of the home language by the KHS group, albeit in an imperfect or asymmetrical manner with respect to register and type of language item.

The KHS group’s greater agility in the non-dominant language, as compared to the USA group, is also reflected in their proficiency scores, which serve as an additional proxy for usage experience. Overall proficiency in Korean was found to be significantly higher in the KHS group than in the USA group. While the proficiency scores were positively associated with reaction time patterns across both groups (i.e., higher scores corresponded with shorter reaction times), these scores exhibited an asymmetric relationship with acceptability rating patterns. Specifically, whereas the proficiency scores correlated positively with the ratings for condition (c) within the USA group (indicating that higher proficiency was associated with higher ratings), the scores correlated negatively with the ratings for the same condition within the KHS group (indicating that higher proficiency was linked to lower ratings). These divergent trends imply that, although higher proficiency in the target language could enhance overall processing efficiency for both learner groups, it may not necessarily have facilitated the acquisition of the target knowledge reinforced in a non-target-like manner through formal instruction, as observed in USA.

In this regard, the finding that the three groups exhibited no substantial differences in acceptability ratings for the infelicitous-yet-grammatical condition (b)—with these ratings remaining largely unaffected by proficiency scores in the two learner groups—opens up several possibilities. For example, the presence of the honorific nominative case marker (-kkeyse) may have served as a sufficient cue, reducing learners’ sensitivity to the presence or absence of the honorific verbal suffix. Alternatively, the local pairing of an honorifiable subject with the honorific nominative case marker itself may have enabled learners to preserve a certain degree of subject honorification. As our experimental design did not vary the honorific status of the nominative case marker attached to honorifiable subjects, our study does not directly speak to the validity of these alternatives. Consequently, further investigation into this matter is warranted.

Meanwhile, as this study focused exclusively on morphosyntactic features involving subject honorification, it did not consider pragmatic factors or Korean-specific cultural norms that may influence learners’ perception and processing of honorification. For instance, our findings do not directly speak to learners’ nuanced understanding of the social implications of using a person’s first name, which was present in some test sentences, in relation to social hierarchy. In this respect, future research should integrate pragmatic and cultural dimensions when exploring learners’ understanding of Korean subject honorification, particularly those with diverse language-use experiences.