Abstract

This study examines how several gender-encoding strategies in Spanish and social factors influence gender perception, reinforcing or mitigating a sexist male bias. Using an experimental design, we tested four linguistic conditions in a job recruitment context: masculine forms (theoretically generic), gender-splits, epicenes, and non-binary neomorpheme “-e”. After reading a profile in one of these conditions, 837 participants (52% women) selected an image of a woman or man. Results show that masculine forms lead to the lowest selection of female candidates, manifesting a male bias. In contrast, gender-fair language (GFL) strategies, particularly the neomorpheme (les candidates), elicited the highest selection of female images. Importantly, not only did linguistic factors and participants’ gender identity influence results—with male participants selecting significantly more men in the masculine condition, but affinity with feminist movements and LGBTQIA+ communities or positive attitudes towards GFL also modulated responses—increasing female selections in GFL, but reinforcing male selections in the masculine. Additionally, no extra cognitive cost was found for GFL strategies compared to masculine expressions. These findings highlight the importance, not only of linguistic forms, but of social and attitudinal factors in shaping gender perception, with implications for reducing gender biases in language use and broader efforts toward social equity.

1. Introduction

A male bias in language perception refers to the tendency to interpret expressions that are ambiguous, or which do not include grammatical gender cues (i.e., morphological information on the gender of the referent), as referring to men only (cf. Stahlberg et al., 2007). Experimental research on gender biases over the last decades has shown this male bias to be a persistent phenomenon across languages with or without grammatical gender distinctions1 (Hamilton, 1991; Stahlberg et al., 2007; Garnham et al., 2012, among others).

In this light, and particularly in grammatical gender languages, the traditional use of masculine forms with an intended generic interpretation (that is, to refer to mix-gender groups or to people whose gender is unknown, as for example (1) in Spanish) has become a particularly controversial strategy to refer to people (Heap, 2024).

- (1)

- Los candidatos al puesto deben tener un título en derecho laboral.det.m candidates.m to.the position must have a title in law labor“Candidates to the position must have a degree in labor law.”

Focusing on grammatical gender languages, in the current debate on gender perception, two relevant questions are still unresolved. The first issue regards the interpretation of masculine forms with a (theoretically) generic interpretation: Can the use of masculine forms lead to a cognitive gender bias?2 This is relevant because such a bias could increase inequalities in the social sphere (for Spanish, see Bengoechea & Calero Vaquera, 2003; Bengoechea, 2008; Guerrero Salazar, 2020, a.o.). The second issue regards the so-called gender-fair language (GFL) strategies,3 which aim to avoid the effects of sexism, discrimination or bias towards a particular sex or social gender, and androcentrism in language, a perspective that takes the masculine and men as the standard norm for humanity (cf. Sczesny et al., 2016). Given that GFL strategies are regarded as more inclusive ways to represent people (Sarrasin et al., 2012; Stout & Dasgupta, 2011; Douglas & Sutton, 2014), can the use of these strategies influence gender perception and avoid a male bias?

Empirical research on the perception of masculine forms with an intended generic interpretation can be found in languages like German (for a review, see Braun et al., 2005), French (e.g., Brauer & Landry, 2008; Chatard et al., 2005; Gygax & Gabriel, 2008), or Norwegian (e.g., Gabriel & Gygax, 2008). Regarding the Spanish language, previous studies have investigated whether a speaker’s gender identity is relevant with regard to the processing of masculine vs. feminine nouns (Domínguez et al., 1999), grammatical gender assignment by Spanish-speaking children (Pérez-Pereira, 1991), children’s acquisition of traditional gender roles (Solbes-Canales et al., 2020), gender stereotypes (Yeaton et al., 2023; Molinaro et al., 2016), attitudes towards inclusive language morphemes (Román Irizarry, 2021), or sexist biases in everyday communication (Ariño-Bizarro & Ibarretxe-Antuñano, 2024), among other topics. However, there are currently few studies that have examined how social factors of the reader (gender identity, attitudes towards GFL, etc.) influence the way readers represent the referent depending on which linguistic forms are used (masculine vs. GFL strategies). This is especially true for the Spanish language, as Heap (2024, p. 226) points out: “There is still a great need for studies based on empirical experiments that indirectly investigate, with Spanish-speaking populations, the spontaneous mental representations (i.e., images, names, and descriptions) evoked by different ways of referring to groups of human beings.” Indeed, well-controlled empirical studies are particularly necessary in this language, given that defenders of the traditional use of so-called masculine generics (e.g., Bosque Muñoz, 2012; Escandell-Vidal, 2020; Mendívil Giró, 2020; Real Academia Española, 2020) claim that the generic interpretation of masculine forms is widespread and easily accessed, but, crucially, they do not usually cite experimental empirical studies on gender perception for Spanish (nor for other languages) to support their claim (Heap, 2024).

The present paper tries to fill these gaps by setting the following two main objectives: (i) to examine the validity and effectiveness of four different modalities used to encode gender in Spanish, concretely, in texts related to the workplace, and to determine whether these modalities for referring to people4 maintain or avoid a male bias; and (ii) to study how certain sociodemographic factors that have been disregarded in most previous studies (such as gender identity or attitudes towards feminism and GFL) can affect gender perception. Finally, as a secondary, exploratory objective, this study aims to assess whether reading a text written with inclusive language strategies is more cognitively demanding than using other strategies to represent people, such as masculine forms.

2. Gender Perception in Recruitment Situations and Perception of Not-So-Generic Masculine Forms and GFL Strategies in Spanish

Across nearly four decades of research on Spanish generic masculine forms, studies consistently indicate that masculine expressions tend to generate a bias toward specifically male interpretations rather than truly generic interpretations (see Heap, 2024 for a review, and Stetie & Zunino, 2022). Research on gender perception in Spanish—from earlier works such as Perissinotto (1983, 1985), Carreiras et al. (1996), and Nissen (1997) to more recent studies by Calero Fernández (2006), Gómez Sánchez (2018), Anaya Ramírez (2020), Anaya Ramírez et al. (2022), Kaufmann and Bohner (2014), and Stetie and Zunino (2022)—clearly supports the idea that masculine forms tend to be interpreted as male specific, and not with a generic, mixed-gender interpretation. However, previous studies contrasting GFL and masculine expressions regarding the interpretation of the referent’s gender in Spanish have not experimentally controlled how factors such as participants’ gender identity and sexist attitudes may interact with particular linguistic forms in shaping gender perception. Our study contributes to the field by incorporating these aspects, demonstrating that certain grammatical forms may be interpreted differently depending on the reader’s gender and attitudes towards gender and language-related matters. We now turn to reviewing the main results of these relevant previous studies as well as some of their limitations and open questions.5

As early as the 1980s, Perissinotto (1983) examined oral sentence interpretation with the word “hombre” “man” in theoretically generic contexts (such as “Todo hombre tiene derecho de entrar en la república y salir de ella” “Every man has the right to get into and out of the republic”) within a group of 140 university students in Mexico. Results showed that these male forms were interpreted as referring exclusively to men, rather than women and men. This was the first experimental study in Spanish that raised doubts about the generic function of masculine forms, suggesting that they only work in highly self-monitored speech (i.e., not in spontaneous sentence comprehension), which is hardly the most common mode. However, this study had a few limitations, since the gender of participants was not considered as a possible modulating factor, and the sample size was relatively small.

In a later experiment, Perissinotto (1985) developed a sentence-completion task that was carried out by 89 university students in Mexico. The study found that masculine forms were frequently interpreted exclusively (as referring to men only) rather than generically. The study noted the emergence of abbreviated gender-split forms with a slash (that is, duplications such as “alumno/a” “student.m/f”, “maestro/a” “teacher.m/f”). However, the study could not take into account individual differences based on gender identity due to the small sample size and the imbalance among participants (60 women, 29 men).

Considering both linguistic forms and stereotypical information, Carreiras et al. (1996) measured reading times for sentences that included masculine role nouns6 with different gender stereotypes (stereotypically female, male or neutral). The authors conducted several experiments with small groups of university students in the Canary Islands (48, 32, and 72 participants) and found that masculine nouns in the singular form were interpreted as referring to men and not to women, probably influenced by the grammatically masculine form and reinforced by social stereotypes. Moreover, reading times were slower when there was a mismatch between gender stereotypes (e.g., male stereotype associated with the role noun carpenter) and grammatical gender markers (e.g., grammatically feminine form such as “la carpintera” “the (female) carpenter”), indicating a higher cognitive load for the integration of opposite cues.

One of the first studies that examined gender perception with masculine forms in Spanish and compared it with GFL strategies was Nissen (1997). The study analysed 196 Spanish university students’ written responses to sentences containing masculine forms (“los alumnos” “the.m students.m”), collective or epicene nouns (“el alumnado” “the.m student.body.m”), or so-called pair coordination or gender-split forms (“los alumnos y alumnas” “the.m students.m and students.f”). Results showed that masculine forms functioned generically in less than half of the cases, with differences between male and female participants. A limitation of the study is that responses were not spontaneous, as participants took the survey home to complete and had time to reflect before finishing the task. Nissen (2013) includes a follow-up study of 266 Spanish university students applying the same methodology after a ten-year gap. Results suggested that by 2005, masculine generics had lost their strong male bias as seen in 1995, while gender-split forms still prompted more female references. It has to be noted, though, that for both studies, gender distribution of the participants was not detailed. Furthermore, the responses cannot be considered spontaneous, as participants took the survey home to complete and, therefore, had time to reflect before finishing the task. These two caveats are likely to explain why these results diverged from results of other studies (see discussion on this point in Heap, 2024).

In Calero Fernández (2006), the author carried out a questionnaire with no time requirements among 54 Spanish-speaking adults in Catalonia (27 men, 27 women) to analyse how participants interpreted masculine forms in intended generic contexts. Results showed that, initially, participants applied a male-biased interpretation, but later on adjusted to a generic interpretation upon encountering certain sentences that made them reflect, as gathered from participants’ testimonies (Calero Fernández, 2006, p. 257).7 The findings of the study suggest that the ambiguity of masculine forms contributes to inconsistencies in interpretation, which vary depending on the participants’ gender, age, and education. Some limitations of the study were its small sample size, and that responses were not spontaneous (the author notes that “We will have to expose our analytical sample to masculine generics in other ways so that they interpret them unconsciously”; Calero Fernández, 2006, p. 271).

Based on Nissen’s work, Kaufmann and Bohner’s (2014) study examined 195 Chilean university students’ (83 women, 112 men) written responses to short stories where people were referred to either with masculine plural forms (“los estudiantes”), forms with the non-binary symbol “-x”8 (“lxs amigxs”), or gender-split forms with slash (“los/las estudiantes”). Results showed that masculine forms evoked a male bias, while slash and “-x”-forms reduced this bias, particularly among female participants. Thus, participant gender modulated results (concretely, men generally had a stronger male bias than women), but there was no effect of the participants’ level of ambivalent (hostile and benevolent) sexism towards women.9 As for the limitations of the study, response spontaneity was unclear, as the time limit to write the continuation of the story was not specified.

The experiment in Gómez Sánchez (2018) involved a sentence completion task as a continuation of a short story, inspired by the studies of Nissen (2013) and Kaufmann and Bohner (2014). Interestingly, the study involved university students in the United States learning Spanish as a second language at an advanced level. Results showed that, even among learners of Spanish as a second language, masculine forms evoked more male images, and that this bias can be reduced by using alternative forms.

The works by Anaya Ramírez (2020) and Anaya Ramírez et al. (2022) were inspired by Carreiras et al. (1996) and included a sentence-continuation task in which, first, participants read a sentence with a plural role noun and different stereotypes, and then had to judge the adequacy of a following statement with either a female or a male anaphora. Results showed a bias towards exclusively male interpretations of stereotypically masculine role nouns (“Los bomberos fueron capacitados para atender emergencias. Uno/*Una realizó varias preguntas durante la presentación” “The.m firefighters.m were trained to respond to emergencies. One (male)/*One (female) asked several questions during the presentation”). In contrast, no such bias was found with stereotypically feminine nouns (such as manicurists, “los manicuristas … uno/una”) nor with stereotypically neutral nouns (such as clients, “los clientes … uno/una”). Moreover, attitudes towards inclusive language modulated results: participants who have more positive attitudes towards GFL tended to favor a more generic interpretation of masculine forms for stereotypically male nouns (in contrast to the findings in other gender perception studies, as shown below). However, results should be taken carefully as the study included a small sample size, although balanced for gender (36 university students in Mexico, 18 women and 18 men).

More recently, Stetie and Zunino (2022) measured sentence comprehension and response times for role names written with masculine forms (“maestros”) or with the non-binary forms “-x” (“maestrxs”) and “-e” (“maestres”). In total, 515 Argentinian Spanish speakers participated in the study, and results showed that masculine forms did not function clearly as generics, with responses varying based on the stereotypicality of the role name. In contrast, non-binary forms (“-x”, “-e”) consistently led to generic, mixed-gender interpretations. Moreover, a potential effect of participant gender was found: women were more likely to interpret masculine forms as referring to men. However, the imbalance between male and female participants (373 women, 123 men, 19 non-cisgender) prevented conclusive results on the effect of participants’ gender over their gender perception being drawn.

In sum, despite following different methodologies and presenting some limitations, findings are consistent: the male-specific (and not the mixed-gender, generic) interpretation appears to be the predominant one with Spanish masculine forms, especially in spontaneous sentence comprehension. Moreover, some GFL strategies appear to reduce or avoid a male interpretation, although there are still few experimental studies available on the topic.10

An asymmetry in gender perception (as we have seen in the results from the previous literature) can have practical consequences, for example, in recruitment situations. In an early study in English, Bem and Bem (1973) already showed that women were more motivated to apply for a particular job when advertising language was explicitly referring to both women and men (e.g., “We need calm, coolheaded men and women with clear friendly voices to do that important job of helping our customers.”). The use of GFL in recruitment situations, therefore, may result in the idea that a gender balance is sought in the advertised position; thus, not only men will be motivated to apply for traditionally male jobs, such as leadership positions (Horvath et al., 2016). Moreover, it has been shown that a male bias in recruitment situations can lead to a preconceived idea that men are the most suitable candidates (Lassonde & O’Brien, 2013), which can result in higher preferences for hiring a man (and thus, produce a self-fulfilling prophecy; Bem & Bem, 1973).

In terms of current empirical research on gender biases, studies such as Lindqvist et al. (2019) are particularly relevant as these authors examine the consequences of using different linguistic modalities to encode gender in the workplace. The authors conducted two experiments, one in English (411 respondents, 256 men, 150 women, 3 non-binary people, and 2 participants who did not disclose their gender) and another one in Swedish (417 participants, 303 women, and 85 men). The authors’ objective was to measure the perception of different gender representation strategies, including the use of neologisms to avoid gender binarism. Specifically, participants in the two experiments read the description of a person who is applying to a gender-neutral job (that is, in a job sector that is considered gender-balanced). The authors created professional summaries in which the job applicant was referred to using one of these linguistic strategies: (1) nouns and pronouns without grammatical gender marking (as in the English expression “the applicant” or singular “they”); (2) gender-split forms (pairs like “he/she” in English); or (3) newly created gender-neutral pronouns (English neopronoun “ze” and Swedish “hen”). After reading the professional summary in one of the conditions, participants indicated who they thought the job candidate was, selecting from four possible images (two women and two men). The answer was coded as “woman” or “man”, depending on the gender of the selected person.

The results of both experiments indicated that traditionally used forms lacking gender marking generate a masculine bias in both English and Swedish. Crucially, the strategy of feminisation by using gender-split forms and the new gender-neutral pronouns avoided this gender bias.

A limitation of the study in Lindqvist et al. (2019) is that, although it examined how some different linguistic modalities affect gender perception, it did not consider that some individual and social variables (such as gender identity of the participants, or their attitudes towards GFL or feminism, more generally) could affect the results. We now turn to review some factors that have been shown to influence gender perception in previous studies in different languages.

First, early work on gender perception already indicated that one’s gender identity can affect our representation of other people (Khoroshahi, 1989, for English). However, studies in different languages and with diverse methodologies have shown mixed results. For example, some studies suggest that women showed an in-group bias and tended to associate expressions about people more easily with a female referent (that is, with their own gender) than with a male referent, and vice versa (Harrison & Passero, 1975; and Prentice, 1994, for English, and Klein, 1988; Braun et al., 2005, for German). In contrast, the results in Stetie and Zunino (2022) previously discussed suggest that women have a greater tendency than men to interpret masculine forms as referring to men only. However, Kaufmann and Bohner (2014) found the reverse results with Chilean speakers: men presented a more marked male bias with masculine forms, a bias that was maintained in the non-binary condition with “-x” (whereas women did not show a male bias in the same non-binary condition).

In addition, attitudes towards language reforms, non-sexist language uses or attitudes towards feminism, in general, have shown quite diverse effects in different studies. As we have previously mentioned, Anaya Ramírez (2020) and Anaya Ramírez et al. (2022) showed that positive attitudes towards GFL tend to favor a more generic, mixed-gender interpretation of masculine forms. Similarly, Khoroshahi (1989) observed in English that women who use inclusive language have more feminine associations than others, even with grammatically masculine forms (such as English “he” with a theoretically generic meaning).11 Although the results in these studies suggest that people (and particularly women) with positive attitudes towards GFL tend to have a less male-biased perception, the results in Stahlberg and Sczesny (2001) clash with this potential generalisation. In this later experimental study in German, participants had to decide as quickly as possible whether an image of a woman or a man could be assigned to a certain category of people expressed with either a masculine form, gender splits, or capital “I” (e.g., “LehrerIn” “teacher”, both male and female). Results showed that speakers with a positive attitude towards GFL were quicker to identify a woman as politician, athlete, etc., when this term was named following a GFL strategy such as capital “I” than when a masculine form was used.12 The authors proposed that participants with positive attitudes towards GFL probably expect a feminine grammatical form to designate some woman, rather than a masculine form.

Furthermore, Kaufmann and Bohner (2014) discuss in their work how participants’ level of ambivalent sexism may affect gender perception. To check this intuition, they included an internationally validated test called the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI) by Glick and Fiske (1996). This test includes two correlated subscales: hostile sexism, which represents an antipathy against women (especially those who do not conform to traditional roles), and benevolent sexism, which captures more subtle, and seemingly positive, stereotypical attitudes toward women that are nonetheless sexist, since they restrict women to certain roles and images, and contribute to keeping women subordinated to men (e.g., “Women should be cherished and protected by men.”). Hence, the ASI provides a reliable and general measure of sexism in its ambivalent form by collapsing two indices (subscales). In Kaufmann and Bohner’s (2014) study with Chilean speakers, both hostile and benevolent sexism were reliably assessed, but showed no effect on gender perception. This result would suggest that the effect of language form may be independent of people’s level of ambivalent sexism, although further experimental work seems necessary to support that claim.

Building on these findings, it appears that several factors, such as the choice of linguistic formula to refer to people, gender identity, and attitudes towards GFL or feminism, for instance,13 seem to play a role in perception and may even interact among them. In this light, we consider it relevant to further study how all the aforementioned factors can affect the interpretation of different modalities to refer to people.

With that purpose in mind, we now turn to describe the experimental study on gender perception we carried out with adult speakers of Spanish in Spain. Given the current complex and heated debate on the perception and use of masculine “generics” in this language, and on the use of GFL strategies to potentially avoid social asymmetries (cf. Bengoechea, 2003, 2008; Heap, 2024; Vela-Plo & Ortega-Andrés, 2025), we conducted an experiment following the job recruitment scenario from Lindqvist et al. (2019). Here, we examined how masculine forms and some GFL strategies to refer to people influence gender perception and potentially interact with other individual factors (such as gender identity, attitudes towards GFL, and levels of ambivalent sexism).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

Participants were recruited either via the “Prolific” platform (www.prolific.co/) or online through social media. Overall, 1240 data entries were registered in the experimental outcome. The data were filtered,14 and the final pool consisted of 837 cisgender people, 442 women and 395 men (18–75 years old, mean age = 31.52, SD = 9.85).15

3.2. Tasks and Materials

Participants had to complete an online survey in Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com) consisting of several parts. First, they had to indicate their age, gender, and main language for communication. Then, based on the methodology in Lindqvist et al. (2019), participants were asked to read a single initial text, that is, the description of a job candidate, clearly written by a professional recruitment agency in a job recruitment context (a position in a law firm, as Carreiras et al. (1996) shows that, for Spanish speakers, law is considered a gender-neutral profession). Crucially, the text was written in one of the following four linguistic strategies of gender representation (i.e., a between-subjects design was adopted). The number of words for each condition was adjusted (between 2015 and 228 words16):

- masculine: masculine forms with an intended generic meaning, such as “Los candidatos tienen entre 25 y 35 años” “the.m candidates.m are between 25 and 35 years old”;

- epicene: epicene nouns, as in “Las personas que se presentan al puesto tienen entre 25 y 35 años” “the.f people.f that apply for the position are between 25 and 35 years old”, where “personas” refers to either women or men unambiguously; or with expressions which do not specify the gender of the referent, such as “Quienes solicitaron la vacante” “those who applied for the position”;

- split: gender splits and pair coordination, such as “Las y los candidatos tienen entre 25 y 35 años” “the.f and the.m candidates.m are between 25 and 35 years old” (most splits followed the feminine-then-masculine order, and sometimes determiners were coordinated as in las y los candidatos, in other cases nouns (los candidatos y candidatas), or phrases were coordinated (con ellas y con ellos), and slash gender splits were also incorporated (ambiciosas/os));

- neomorpheme: recently created neologisms to avoid gender binarism, such as neomorpheme “-e” in “Les candidates tienen entre 25 y 35 años” “The.n candidates.n are between 25 and 35 years old”, or neopronoun “elle(s)”.

After reading the text, participants had to select one image of a person among four potential candidates (two women and two men) which were randomly presented (see Figure 1). These four images had been selected after a norming study, ensuring that the four persons were considered to be most in line with the described age, and equally nice and feminine/masculine.17

Figure 1.

On the left, example of the text in the condition with the neomorpheme “e”. On the right, the following screen with the experimental task of selecting a preferred picture.

The time taken to read the experimental text (reading times) and the time taken to select the image (response times) were recorded. Three comprehension questions were presented as control and used to filter the data from participants who did not pay attention to the experimental text (see note 16 regarding data cleaning). After that, participants had to respond to the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI, a standardised test that has been cross-culturally validated and measures hostile and benevolent sexism towards women; Glick & Fiske, 1996; Glick et al., 2000) so that we could assess whether the score on this inventory could influence the results in the picture selection task. For the present study, the short version of the Spanish adaptation of ASI was used (Bonilla-Algovia, 2021; Bonilla-Algovia & Rivas-Rivero, 2020; Rodríguez et al., 2009). This version was validated in Spain (Rodríguez et al., 2009), Mexico, and El Salvador (Bonilla-Algovia & Rivas-Rivero, 2020): it consists of 12 statements on hostile sexism (6 items; e.g., “Women exaggerate the problems they have at work”) and benevolent sexism (6 items; e.g., “Women should be loved and protected by men”). Responses used a Likert-type scale where 0 meant “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”.

Finally, participants completed a short questionnaire about some personal characteristics (affinity with the feminist movement or affinity with the LGTBIQ+ communities,18 and attitudes towards inclusive language19) to study whether there is a relationship between these socio-demographic traits and the answers given in the main task.

3.3. Hypothesis and Predictions

Taking into account the observation from our review of the previous literature in Section 2, our starting hypotheses and predictions were the following:

- Traditionally used forms and gender-unmarked expressions such as epicenes and masculine forms with an intended generic interpretation were expected to show a masculine bias that other GFL strategies would not induce (based on Lindqvist et al., 2019 and previous studies on Spanish). Thus, our predictions were the following:

- (a)

- masculine and epicene conditions would induce a masculine bias.

- (b)

- split and neomorpheme conditions would avoid a masculine bias.

In other words, we expected that the proportion of choosing an image that represents a woman would be below the 50% in masculine and epicenes conditions, but not in the case of split and neomorpheme conditions. - Based on previous studies with grammatical gender languages, where masculine forms tend to be understood as male-specific, we were expecting to find fewer selections of images of a woman in the masculine condition compared to any of the other three GFL conditions (irrespective of other individual or social factors).

- Furthermore, we expect gender identity to affect gender perception. Based on Kaufmann and Bohner’s (2014) results with Chilean speakers, we predict that female participants will choose more images representing a woman than male participants. Moreover, we expected to find significant interactions between participants’ gender identity and linguistic condition. It is possible that the use of GLF strategies could reduce gender differences, such that men would also choose more pictures of a woman in split and neomorpheme conditions, for instance.

- Kaufmann and Bohner (2014) suggest that the effect of language form may be independent of people’s level of ambivalent sexism. Contrary to this proposal, if male biases in language interpretation are due to social sexism or androcentrism (Stahlberg et al., 2007), one would expect a person’s level of ambivalent sexism to influence gender perception, with people showing higher levels of ambivalent sexism interpreting ambiguous referents primarily as referring to men. Given this latter hypothesis and previous findings on the effects of linguistic forms and gender identity in shaping gender perception, we expected that the score in the ASI would modulate the results in a three-way interaction between condition, participants’ gender identity, and ASI score. Concretely, a higher score in the ASI was expected to imply fewer selections of an image of a woman in the masculine and epicene conditions. We will, for the first time, explore whether this effect is reduced in the case of split and neomorpheme conditions, and whether its strength is different for female and male participants.

- Furthermore, we have planned an exploratory analysis to determine whether individual differences can modulate the results, namely, affinity to the feminist movement, affinity to the LGBTQIA+ movement, and affinity to the use of GFL strategies. We expected participants showing greater affinity to these groups to select more pictures of a woman as a candidate for the job.

- Finally, given the contra GFL argument on the potential higher processing cost of texts written with GFL strategies, reading times, and response times (taken as proxy for difficulty of comprehension) in epicene, split, and neomorpheme GFL conditions were expected to be slower than of those in the masculine condition. That is, reading texts following inclusive language strategies was expected to be more time-consuming than following other traditional representation strategies such as masculine forms in Spanish.

3.4. Data Analysis

To examine the effects of participants’ gender and linguistic condition on the chosen images, we used a generalized linear model (GLM) command from the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015). The dependent variable (DV) was the choice of an image that represents a woman (F) or a man (M). Our predictors were the gender identity of the participants (variable 1) and the linguistic condition (the type of text that participants read before the question: variable 2). Since our main predictor was categorical, we indexed the combinations of the levels of the predictor, instead of fitting the model with the predictors as indicators (see Urrestarazu-Porta, 2025, 23 February 2025). We included the factorial interaction between gender and condition (Variable 1: Variable 2) without an intercept. This approach provided separate estimates for the choices of the picture representing a woman in comparison with the 50%, rather than a baseline comparison, for each combination of gender and condition.

To explore the effect of the ASI on the data, we ran a second analysis adding the ASI as a third predictor (Variable 3). We included two factorial interactions: one interaction between the gender of the participants and the linguistic condition (Variable 1: Variable 2) and one interaction between these two factors and the centered ASI (Variable 1: Variable 2: Variable 3) without an intercept. This approach provided separate estimates for the choices of the picture representing a woman in comparison with the 50%, rather than a baseline comparison, for each combination of gender and condition for the average ASI score. It also provided a separate estimation of each combination in relation to participants’ score in the ASI. This means that the model offered, for example, the estimation of choices of a picture of a woman compared to the 50% by male participants in the split condition as well as the estimation of choices of a picture of a woman by male participants in this condition in relation to their score in the ASI.

All statistical analyses were performed in R 4.4.2 (R Core Team, 2020) with a significance level of α = 0.05. Significant negative estimates have been interpreted as choosing significantly more pictures that represent a man than selecting pictures that represent a woman, and significant positive estimates have been interpreted as choosing significantly more pictures representing a woman than pictures representing a man.

To further explore the effects, we conducted two post hoc contrast analyses using emmeans (Lenth, 2022) and pairwise comparisons. These comparisons allowed us to contrast between conditions, since we are specifically interested in whether some conditions generate or reduce a male bias more than others. First, we computed estimated marginal means (EMMs) for each condition within each gender. In our second contrast analysis, we examined gender differences within each condition. These analyses allowed us to assess whether gender differences emerged within specific conditions, and whether conditions differed within each gender group.

Another exploratory analysis was carried out in order to determine whether affinity to the feminist movement, to the LGBTQIA+ movement, and to GFL strategies modulated the picture selection. These three factors were included as fixed effects in separate analyses, together with the linguistic condition and the gender of the participants in a factorial interaction.

Finally, two additional analyses were conducted to examine whether the experimental condition influenced participants’ reading and response times. Separate linear models were fitted to assess the effect of condition on the time taken to read the scenarios and the time taken to select a response. In both models, the masculine condition was set as the reference level, allowing us to determine whether the other GFL conditions resulted in significantly longer reading or response times.

4. Results

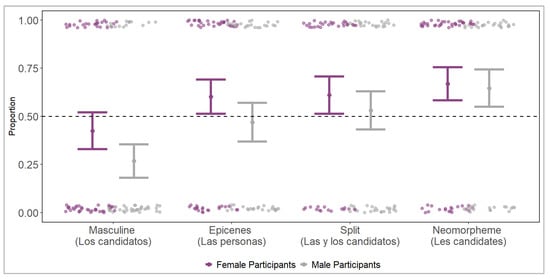

Results regarding the interaction between condition and gender showed the following results (see Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Proportion of selections of images of a woman in each condition. The purple color represents results by female participants, while the gray color represents results by male participants. Error bars represent the 95% of confident interval. Data points represent individual data at the participant level.

- in the split condition, female participants selected significantly more pictures of a woman compared to the 50% of choices (~61%, est. = 0.45, SE = 0.2, z = 2.18, p = 0.03), whereas male participants did not display a statistically significant difference (~53%, est. = 0.12, SE = 0.2, z = 0.6, p = 0.55);

- in the epicene condition, female participants also selected significantly more pictures of a woman compared to the 50% (~60%, est. = 0.41, SE = 0.19, z = 2.19, p = 0.03), whereas male participants did not display a statistically significant difference (~47%, est. = −0.12, SE = 0.2, z = −0.61, p = 0.54);

- in the neomorpheme condition, both female participants (~67%, est. = 0.71, SE = 0.2, z = 3.61, p < 0.001) and male participants (~64%, est. = 0.6, SE = 0.21, z = 2.81, p = 0.005) selected significantly more pictures of a woman than the 50%;

- in contrast, in the masculine condition, male participants selected significantly more pictures of a man than the 50% (~27%, est. = −1.01, SE = 0.22, z = −4.48, p < 0.001), whereas female participants did not display a statistically significant difference (~42%, est. = −0.3, SE = 0.2, z = −1.55, p = 0.12) with the 50%.

Contrasts between conditions showed that, irrespective of gender, participants in the masculine condition selected significantly more pictures of a man (i.e., fewer pictures of a woman) than in any other condition:

- split vs. masculine: female participants est. = 0.75, se = 0.28, z = 2.64, p = 0.04; male participants est. = 1.13, se = 0.3, z = 3.75, p = 0.001;

- epicenes vs. masculine: female participants est. = 0.72, se = 0.27, z = 2.63, p = 0.04; male participants est. = 0.89, se = 0.3, z = 2.93, p = 0.02;

- neomorpheme vs. masculine: female participants est. = 1.01, se = 0.28, z = 3.64, p = 0.001; male participants est. = 1.61, se = 0.31, z = 5.19, p < 0.001.

Additionally, a non-significant trend showed that male participants tended to select fewer pictures of a woman in the epicene condition than in the neomorpheme condition (est. = −0.72, se = 0.29, z = −2.46, p = 0.07). The rest of the contrasts were not significant.20

Contrasts between genders showed that in the masculine condition, female participants selected significantly more pictures of a woman than male participants (females vs. males: est. = 0.7, se = 0.3., z = 2.36, z = 0.02). A trend in the same direction was also found in the epicene condition (est. = 0.53, se = 0.28, z = 1.94, p = 0.05). The rest of the contrasts were not significant.21

Results regarding the interaction between condition and gender for the average score in the ASI show the following:

- in the split condition, female participants selected significantly more pictures of women than the 50%, which means that they selected more pictures of a woman than of a man (est. = 0.6, SE = 0.24, z = 2.49, p = 0.01), whereas male participants did not display any statistically significant difference (est. = 0.17, SE = 0.22, z = 0.74, p = 0.46);

- in the epicene condition, the selection of either female participants (est. = 0.16, SE = 0.22, z = 0.71, p = 0.48) or male participants (est. = −0.1, SE = 0.21, z = −0.48, p = 0.63) did not significantly differ from the 50%;

- in the neomorpheme condition, both female participants (est. = 0.51, SE = 0.22, z = 2.33, p = 0.02) and male participants (est. = 0.52, SE = 0.23, z = 2.31, p = 0.02) selected significantly more pictures of women than the 50%;

- in the masculine condition, male participants selected significantly more pictures of men than the 50% (est. = −0.86, SE = 0.23, z = −3.7, p < 0.001), whereas female participants did not display any statistically significant difference with the 50% (est. = −0.17, SE = 0.22, z = −0.79, p = 0.43).

Contrasts between conditions for the average score in the ASI showed the following results:

- Among female participants, there was no significant difference in picture selection between conditions. Only a trend was found in the contrast between split and masculine conditions, showing that in the split condition there was a tendency towards selecting more pictures of a woman (est. = 0.77, SE = 0.33, z = 2.37, p = 0.08).22

- Male participants selected significantly more pictures of a man in the masculine condition compared to any other condition—to the split condition (split vs. masculine: est. = 1.03, SE = 0.32, z = 3.18, p = 0.008), to the epicene condition (epicene vs. masculine: est. = 0.76, SE = 0.32, z = 2.41, p = 0.07), or to the neomorpheme condition (neomorpheme vs. masculine: est. = 1.39, SE = 0.32, z = 4.27, p < 0.001). The rest of the contrasts showed no statistically significant differences.23

Contrasts between participants’ gender for the average score in the ASI showed that male and female participants behaved with a significant difference only in the masculine condition: female participants selected more pictures of a woman than male participants in this condition (est. = 0.69, SE = 0.32, z = 2.15, p = 0.03).24

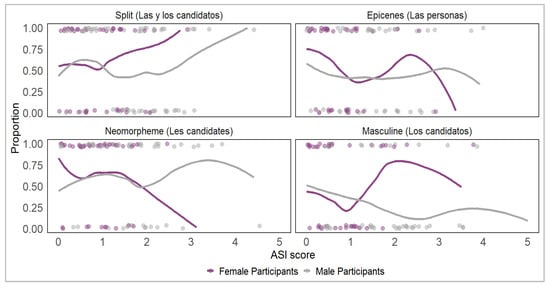

Regarding the interaction between condition, gender, and ASI score, results show the following (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Proportion of selection of images representing a woman (y axis) grouped by condition, gender of participants, and the ASI score (x axis). Data points represent individual data at participant level (selection of a picture of a woman = 1, selection of a picture of a man = 0), which for some ASI scores is only 1 participant.

- in the split condition, the ASI score did not significantly modulate the results (female participants: est. = 0.42, SE = 0.32, z = 1.34, p = 0.18; male participants: est. = −0.11, SE = 0.23, z = −0.46, p = 0.65);

- in the epicene condition, the higher the ASI score, the more pictures of a man selected by female participants (est. = −0.7, SE = 0.31, z = −2.27, p = 0.02). However, the ASI score did not significantly modulate the results of male participants (est. = −0.06, SE = 0.2, z = −0.3, p = 0.77);

- in the neomorpheme condition, the higher the ASI score, the more pictures of a man selected by female participants (est. = −0.6, SE = 0.29, z = −2.02, p = 0.04). However, the ASI score did not significantly modulate the results of male participants (est. = 0.21, SE = 0.21, z = −1, p = 0.31);

- in the masculine condition, in contrast, the higher the ASI score, the more pictures of a man selected by male participants (est. = −0.5, SE = 0.23, z = −2.2, p = 0.03). In this condition, the ASI score did not significantly modulate the results of female participants (est. = 0.36, SE = 0.28, z = 1.31, p = 0.19).

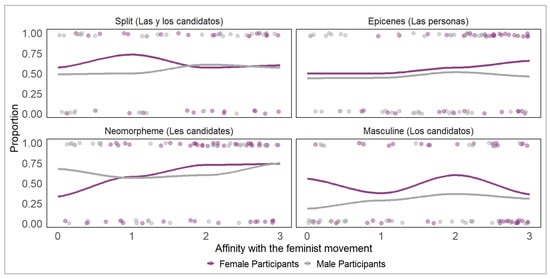

Regarding the exploratory analysis about whether affinity with the feminist movement affected the picture selection task, results from the models were the following (see also Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Proportion of selection of images representing a woman (y axis) grouped by condition, gender of participants, and affinity with the feminist movement (x axis). Data points represent individual data at participant level (selection of a picture of a woman = 1, selection of a picture of a man = 0).

- in the split condition, the higher the affinity with the feminist movement, the more pictures of women selected. This difference was not significant among male participants (est. = 0.13, SE = 0.13, z = 1.03, p = 0.3), and only approached significance among female participants (est. = 0.16, SE = 0.09, z = 1.82, p = 0.07);

- in the epicene condition, for female participants, the higher their affinity with the feminist movement, the more pictures of women selected (est. = 0.2, SE = 0.08, z = 2.57, p = 0.01). No significant difference was found for male participants (est. = −0.03, SE = 0.12, z = −0.24, p = 0.81).

- in the neomorpheme condition, the higher the affinity with the feminist movement, the more pictures of women selected. This was true for both female participants (est. 0.38, SE = 0.09, z = 4.21, p < 0.001) and male participants (est. = 0.3, SE = 0.12, z = 2.41, p = 0.016);

- in contrast, in the masculine condition, the higher the affinity with the feminist movement, the more pictures of a man selected. This effect was significant for male participants (est. = −0.31, SE = 0.13, z = −2.28, p = 0.02), but did not reach significance for female participants (est. = −0.15, SE = 0.08, z = −1.84, p = 0.07).

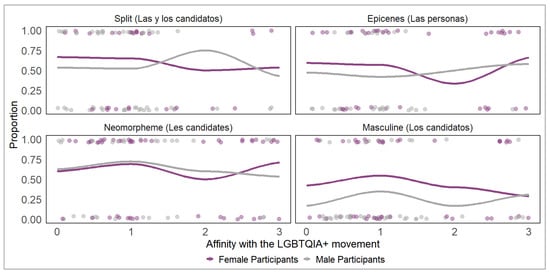

Regarding the exploratory analysis about whether affinity with the LGBTQIA+ communities affected the picture selection task (see Figure 5), results from the models were the following:

Figure 5.

Proportion of selection of images representing a woman (y axis) grouped by condition, gender of participants, and affinity with the LGBTQIA+ communities (x axis). Data points represent individual data at participant level (selection of a picture of a woman = 1, selection of a picture of a man = 0).

- in the split condition, affinity to the LGBTQIA+ communities did not significantly modulate the data, neither for female participants (est. = 0.11, SE = 0.11, z = 0.996, p = 0.32) nor for male participants (est. = 0.104, SE = 0.18, z = 0.268, p = 0.79);

- in the epicene condition, for female participants, the higher their affinity with the LGBTQIA+ communities, the more pictures of women selected (est. = 0.21, SE = 0.1, z = 2.13, p = 0.03). No significant difference was found for male participants (est. = −0.02, SE = 0.14, z = −0.14, p = 0.89);

- in the neomorpheme condition, the higher the affinity with the LGBTQIA+ communities, the more pictures of women selected. This was statistically significant only for female participants (est. 0.33, SE = 0.1, z = 3.24, p = 0.001), and not for male participants (est. = 0.23, SE = 0.15, z = 1.5, p = 0.13);

- in contrast, in the masculine condition, the higher the affinity with the LGBTQIA+ communities, the more pictures of a man selected. This effect was significant for both female participants (est. = −0.23, SE = 0.1, z = −2.24, p = 0.02), and male participants (est. = −0.43, SE = 0.17, z = −2.59, p = 0.01).

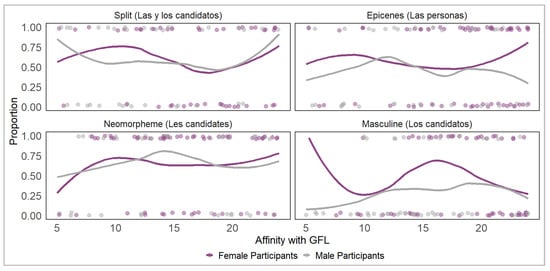

Regarding the exploratory analysis about whether affinity to GFL affected the picture selection task (see Figure 6), results from the models were the following:

Figure 6.

Proportion of selection of images representing a woman (y axis) grouped by condition, gender of participants, and affinity with GFL (x axis). Data points represent individual data at participant level (selection of a picture of a woman = 1, selection of a picture of a man = 0).

- in the split condition, affinity to GFL did not significantly modulate the data for male participants (est. = 0.009, SE = 0.01, z = 0.63, p = 0.53), whereas for female participants there was a trend towards selecting more pictures of women the higher the affinity with GFL (est. = 0.02, SE = 0.01, z = 1.91, p = 0.06);

- in the epicene condition, for female participants, the higher their affinity to GFL, the more pictures of women selected (est. = 0.02, SE = 0.01, z = 2.38, p = 0.02). No significant effect was found for male participants (est. = −0.006, SE = 0.01, z = −0.44, p = 0.66);

- in the neomorpheme condition, the higher the affinity to GFL, the more pictures of women selected. This was statistically significant for both female participants (est. 0.04, SE = 0.01, z = 3.76, p < 0.001) and male participants (est. = 0.03, SE = 0.01, z = 2.5, p = 0.01);

- in contrast, in the masculine condition, the higher the affinity to GFL, the more pictures of a man selected. This effect was significant for male participants (est. = −0.06, SE = 0.01, z = −3.6, p < 0.001), but only approached significance in female participants (est. = −0.02, SE = 0.01, z = −1.85, p = 0.06).

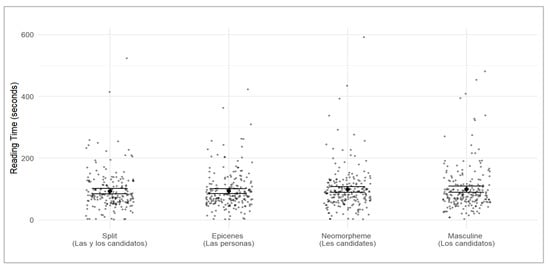

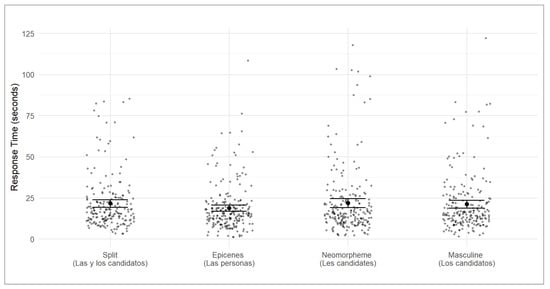

As for the reading25 (Figure 7) and response times26 (Figure 8), analyses carried out through comparisons with the masculine condition presented no significant difference, showing that the time taken to read the experimental text and to answer the picture-selection question was not influenced by how the text was written (whether a GFL strategy was used or not).

Figure 7.

Reading times in seconds (y axis) grouped by condition. Data points represent individual data at participant level (the time taken to read the text for each participant).

Figure 8.

Response times in seconds (y axis) grouped by condition (x axis). Data points represent individual data at participant level (the time taken to select the image for each participant).

5. Discussion

The first objective of the present research was to evaluate whether four different modalities used to encode gender in Spanish maintain or avoid a male bias. Our results show that the proportion of choices of an image of a woman was lower in the masculine condition compared to any of the other three GFL conditions (split, epicene, or neomorpheme conditions). Hence, our results partially differ from those in Lindqvist et al. (2019) for English and Swedish, who found that both masculine and gender unmarked expressions (which could be parallel to our epicene condition) triggered a male bias. This difference could be due to the grammatical properties of a given language27 and the everyday habits of using one or another strategy to refer to people. In the case of languages without grammatical gender marking on nouns, such as English or Swedish, gender unmarked terms and expressions are traditionally (and habitually) employed (as in the candidates); these habitual uses may more easily perpetuate social sexist biases28 than less standard or habitual, more novel, and actively created gender-neutral pronouns in these languages. As Lindqvist et al. (2019, p. 114) suggest “Perhaps new constructions require people to actively think, which might eliminate the gender bias”. Moving back to grammatical gender languages such as Spanish, not using masculine forms and employing epicenes and gender unmarked expressions (or other GFL strategies) may support active thinking that people of any gender (and not only males) are being referred to, which might more easily attenuate or eliminate potential gender biases. If this hypothesis were on the right track, less used expressions would be expected to induce fewer associations with males. The results from our study suggest that this prediction may be accurate: in Spanish, the text in the neomorpheme condition that includes expressions with the recently created non-binary morpheme “-e”, such as les candidates, elicited the highest selection of a picture of a woman (see Figure 2).29

Moreover, our results show that texts written with masculine forms (even when they are intended to have a generic interpretation) tend to be understood as male specific (both in the average score of the ASI and without taking levels of ambivalent sexism into consideration) and, particularly so, among male Spanish speakers, as shown in Figure 2. Although female participants’ responses did not significantly differ from the 50% of choices of images of a woman or a man in the masculine condition, it is worth noting that contrasts between conditions and gender did show significant differences for female participants when comparing the masculine condition with the other conditions. That is, women tended to select more images of a man after reading a text written with masculine forms in comparison with a text written with GFL (see note 22). Thus, it is clear that the choice of linguistic strategy to refer to people is not innocuous for women neither, given that: (i), although non-significant, female participants in the masculine condition chose numerically more images of a man than images of a woman (58% of male images selected), and, in clear contrast (ii) female participants in the three GFL conditions (epicenes, splits, and neomorpheme) chose statistically more images of a woman than images of a man; that (iii) female participants chose significantly more images of a woman in the GFL conditions than in the masculine condition; and that (iv) the higher the scores in the ambivalent sexism scale, the more images of a man that were selected by female participants in the epicenes and neomorpheme conditions. Moving to male participants, the interaction between condition and gender (both in the average score of the ASI and without considering it) was significant in the case of the masculine condition (more choices of an image of a man) and the neomorpheme condition (more choices of an image of a woman). This observation reflects the view that different linguistic strategies affect individuals in diverse ways, depending on social factors like their gender identity and their levels of ambivalent sexism. Given this significant interaction between participants’ gender identity, levels of sexism, and linguistic condition, future studies on gender perception should consider those factors for more accurate descriptions.

In light of this, our results align with the observation in previous studies that masculine forms do not tend to be interpreted generically; rather, they may induce a male bias in Spanish (Kaufmann & Bohner, 2014; Stetie & Zunino, 2022, a.o.) and in other grammatical gender languages with masculine “generics” such as French or German (as shown in Chatard et al., 2005; Gygax et al., 2008, 2012; Vervecken et al., 2015; Braun et al., 2005; Stahlberg et al., 2007, among many others). And, importantly, the results from this study clearly evidence that the linguistic forms used to encode gender in a given language influence gender perception and may result in either maintaining sexist social biases or avoiding them. This is a result with relevant consequences, not only in linguistic terms, but in the search for social equity.30

Our second aim was to study whether certain sociodemographic factors (gender, attitudes towards GFL, etc.) affect gender perception.31 The results from our study show a three-way interaction between linguistic condition, participants’ gender identity, and ASI score. The analysis of this interaction shows that the level of ambivalent sexism does not affect candidate selection in texts written with gender splits such as las y los candidatos, where women are explicitly referred to (and thus, made visible). In contrast, higher scores in ASI correlate with more choices of an image of a man in the following cases: by male speakers when the text is written with masculine forms; and by female participants when the text is written with one of the GFL strategies when women are not explicitly mentioned (that is, expressions with non-binary neomorpheme -e, or epicenes and gender unmarked expressions). These results suggest that gender-inclusive language strategies also affect gender perception differently depending on people’s gender identity and ambivalent sexism, with gender splits promoting more balanced representations, while masculine forms may reinforce existing sexist biases.

Regarding the question of whether affinity to the feminist and LGBTQIA+ movements and to the use of GFL strategies can affect gender perception, we expected participants who showed greater affinity to these groups to select more pictures of a woman as a candidate for the job. Nevertheless, the results we obtained are more complex than that. Participants with greater affinity to these movements and to GFL use selected more pictures of a woman in the gender neutralization GFL conditions (i.e., neomorpheme and epicene conditions); and, in the split condition, only those with greater affinity to the feminist movement chose more pictures of a woman. Interestingly, in the masculine condition, the opposite effect occurred: the greater the adherence to feminist movements, LGBTQIA+ communities and GFL use, the more pictures of a man were selected32 (and particularly so for male participants). This could suggest an implicit reinforcement of traditional gender associations when masculine forms are used, possibly due to participants’ awareness of linguistic biases, or to an expectation that masculine forms signal male referents. That is, to these people, masculine forms are not used generically, but as male exclusive. Overall, these findings indicate that support for feminist, LGBTQIA+, and gender inclusive language movements can influence gender perception, but its effects vary across different linguistic contexts, sometimes reinforcing or counteracting sexist biases, probably depending on people’s expectations.

The final exploratory question was whether reading texts that follow inclusive language strategies is more cognitively demanding than using masculine forms in Spanish. Some opponents of GFL argue that reading texts written with GFL strategies requires higher processing cost than if the texts were written with masculine forms in Spanish. The results of our study showed no significant differences in reading and response times depending on the linguistic condition.33 This, in turn, suggests that the time taken to read a text and to answer questions about it does not significantly differ if a GFL strategy is used or not. In a review of arguments in favor and against GFL use, Vela-Plo and Ortega-Andrés (2025) examine empirical studies that challenge the notion that GFL is particularly difficult or cognitively demanding (see, for instance, Parks & Roberton, 1998). Results from empirical studies in different languages indicate that reading texts employing GFL does not require more effort compared to those using masculine forms: research has shown that neither text quality (Rothmund & Christmann, 2002) nor cognitive processing (Braun et al., 2007) is negatively affected by GFL. Additionally, comparisons between GFL texts and texts written with masculine forms reveal no significant differences in readability or aesthetic appeal (Blake & Klimmt, 2010). However, it is crucial to note that these studies assess cognitive effort from the reader’s perspective, rather than that of the speaker.

6. Conclusions

This study examines not only how different gender-encoding strategies in Spanish influence gender perception, and may inadvertently reinforce existing sexist biases, but also how social factors such as gender identity, people’s level of ambivalent sexism, or attitudes towards feminism, LGBTQIA+, and gender-fair language (GFL) affect gender perception. Regarding the first question, results indicate that texts using masculine forms lead to a lower selection of female candidates in a job-seeking environment compared to GFL strategies, such as gender splits, epicenes, or non-binary neomorpheme “-e” in Spanish. These findings contrast with prior studies with languages without grammatical gender such as English and Swedish, suggesting that language structure and habitual linguistic usage influence gender perception differently across linguistic systems. Moreover, the neomorpheme condition (expressions with non-binary “-e”) resulted in the highest selection of images of a woman, supporting the idea that newer, less traditional gender-inclusive strategies may be more effective in mitigating a male bias. Additionally, the results from this experimental study show that masculine “generics” were mainly interpreted as male-specific, particularly by male participants, reinforcing prior research with languages with grammatical gender (such as French or German) indicating that so-called masculine generics do not function as truly mixed-gender or inclusive forms. In light of this, masculine forms may result in an unconscious male bias in spontaneous interpretations (as also suggested in other studies with grammatical gender languages). In contrast, gender-fair language strategies—that is, employing epicene nouns, expressions which do not specify the gender of the referent, gender splits, or recently created neologisms to avoid gender binarism, such as neomorpheme “-e”—appear to be more effective in avoiding this male bias in a grammatical gender language like Spanish.

Secondly, as a novelty in comparison to previous work on gender perception in Spanish, the present study explored how participants’ gender identity as well as their level of ambivalent sexism (according to the Ambivalent Sexist Inventory (ASI)) affect gender perception by Spanish speakers in Spain. The findings indicate that a participant’s gender identity significantly influences how linguistic forms are interpreted: male participants showed a stronger male bias in the masculine condition, while female participants demonstrated a more balanced perception across conditions. Furthermore, ambivalent sexism levels affected gender perception differently depending on the linguistic strategy used, with gender-split strategies mitigating bias more effectively than masculine or gender-neutralized forms. This study also explored the role of affinity to feminist and LGBTQIA+ movements in shaping gender perception. While higher adherence to these movements generally led to a greater selection of female-representing images in GFL conditions, the opposite occurred in the masculine condition, suggesting an implicit reinforcement of male associations when masculine forms are used. These findings highlight the complex interplay between ideological stances and linguistic interpretation.

Finally, our exploratory analysis addressed the claim that GFL strategies impose a higher cognitive processing cost. Contrary to this assumption, our results found no significant differences in reading or response times across linguistic conditions, aligning with previous research demonstrating that GFL does not hinder comprehension or processing fluency.

Overall, this study provides novel insights into how linguistic structures and social biases influence gender perception. By demonstrating that different GFL strategies vary in their effectiveness at counteracting male bias, and that gender perception is shaped by linguistic conditions and sociocultural factors. These findings have significant implications for both linguistic and psychological research, as well as for broader efforts toward social equity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.V.-P. and M.D.P.; Methodology, L.V.-P., M.D.P. and M.O.-A.; Software, M.D.P.; Formal Analysis, M.D.P. and M.O.-A.; Investigation, L.V.-P., M.D.P. and M.O.-A.; Data Curation, M.D.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, L.V.-P. and M.O.-A.; Writing—Review & Editing, L.V.-P., M.D.P. and M.O.-A.; Visualization, M.O.-A.; Supervision, L.V.-P.; Project Administration, L.V.-P.; Funding Acquisition, L.V.-P., M.D.P. and M.O.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been partially funded by the Theoretical Linguistics Group HiTT (IT1537-22) at the UPV/EHU and by Emakunde- Instituto Vasco de la Mujer, Grants for research work on equality between women and men for the year 2023 (2023-BTI1-TE-05).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects of the University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU (protocol code 004/2022 and date of approval 22 April 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

All the original materials presented in this study, code for analysis, and raw data are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/u3brc.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions, which have improved the quality and clarity of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of this manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GFL | Gender-fair language |

| ASI | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory |

| LGTBQIA+ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, and the “+” represents other identities not explicitly listed, encompassing the diverse range of sexual orientations and gender identities |

Notes

| 1 | Stahlberg et al. (2007) identify three general types of languages based on how they reflect gender: grammatical gender languages (such as Spanish), natural gender languages, and genderless languages; though many languages may not fit perfectly into just one category. Natural gender languages, like English or Swedish, do not assign grammatical gender to most nouns. Terms such as student or doctor have no grammatical marking of gender and can refer to people of any gender. However, personal pronouns (like she or his) reflect the gender of the referent. The selection of personal pronouns in languages within this category is largely based on extralinguistic criteria of animacy and gender. In the case of genderless languages, such as Finnish, Turkish, Persian, Chinese, and Swahili, these languages lack grammatical gender entirely. They do not distinguish gender in nouns nor pronouns, allowing most words to refer to both males and females without any grammatical cue. Regarding the focus of this study, grammatical gender languages, Stahlberg et al. (2007) indicate that grammatical gender exists in various language families, including Slavic (e.g., Russian), Germanic (e.g., German), Indo-Aryan (e.g., Hindi), Semitic (e.g., Hebrew), and Romance (e.g., Spanish), among others. In these languages, every noun is classified as either feminine, masculine, or sometimes neuter. While the grammatical gender of inanimate nouns like “pencil”, “hope”, or “disease” does not indicate social gender, there is a strong correlation between grammatical and social gender in most personal nouns. As a result, words such as “mother”, “teacher”, or “friend” are assigned a feminine or masculine grammatical gender based on the gender of the person they describe. However, some exceptions exist where grammatical and social gender do not align, such as the German word das Mädchen (“girl”), which is neuter, or epicene nouns like Spanish la víctima (“the victim”) or la persona (“the person”), which are grammatically feminine but can refer to individuals of any gender. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Regarding Spanish, García Meseguer (1994) pointed out that there is a difference between the use of masculine “generics” in examples like (i), not considered sexist by that author, and in sentences like (ii), which he did consider clearly sexist for imposing an undoubtedly androcentric (and heterosexual) perspective within a generic statement about human beings:

The question currently being debated is can the use of masculine forms, sometimes not considered sexist by some experts in linguistics or grammar (as in example (i)), entail a cognitive gender bias that perpetuates existing inequalities in the social sphere? | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Gender-Fair Language (GFL) comprises those linguistic strategies that aim at reducing gender stereotyping and discrimination (Sczesny et al., 2016). In the field of person perception within social psychology, stereotypes have been shown to play a central role in shaping how listeners construe social meaning in context (e.g., Macrae & Bodenhausen, 2001; Greenwald et al., 2002). Following Levon (2014), stereotypes can be defined as cognitive structures that link group concepts with collections of both trait attributes and social roles. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | This article focuses on the linguistic representation of women and men. Theoretical and experimental studies on the representation of gender identities outside this binary approach are still scarce and future research should address this relevant issue. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Several experimental studies on gender perception in Spanish present themselves as the first of their kind, often overlooking previous research in the field. As Heap (2024) notes, this misconception appears widespread, and the review of previous work in Spanish in Section 2 aims at generating greater awareness of past studies so as to foster more coherent research that builds on increasing knowledge rather than presenting isolated findings. See also note 27. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Role nouns refer to the function or position that someone may have in an organization, in society, or in a relationship. These can be professions (teacher, lawyer) or other social roles (client, student, spouse). | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | The results show that, initially, participants follow a male bias. To the first sentences of the questionnaire, participants apply “instinctively what I suppose is the general rule—that is, to consider the masculine as almost always, if not always, as specific—in the first sentences they received, until they came across a sentence that made them reflect” (Calero Fernández, 2006, p. 257, our translation). That is, it is only after encountering further sentences with masculine forms that participants reflect on the masculine forms and may interpret it in a generic, mixed-gender sense. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Martínez (2019, p. 189) notes that while the “@” symbol was initially popular as a sign of inclusivity and an alternative to gendered splits in writing, it was gradually replaced by the “x” form. In Spanish, this “x”, and later morpheme “-e”, have been proposed as attempts to provide representation for non-binary groups (see Kosnick, 2019 and Knisely, 2021 for similar proposals in French, and Marini-Maio, 2016 for Italian). An example of this is the term latinx, which was added to the Merriam-Webster dictionary in 2018. However, as a reviewer points out, it should be noted that these forms are ambiguous between a non-binary referent and a generic/inclusive referent. Unlike other inclusive strategies such as non-binary “x” or “@”, morpheme “-e” is fully pronounceable, making it more adaptable to spoken language (Martínez, 2019). Despite its growing presence (particularly in some varieties of Spanish, such as Argentinian Spanish), the use of morpheme “-e” remains unofficial and controversial from a normative perspective, as Real Academia Española’s (2020, p. 74, our translation) claims demonstrate: “The use of “@” or the letters ‘e’ and ‘x’ as supposed markers of inclusive gender is foreign to Spanish morphology and unnecessary, as the grammatical masculine already fulfills that function as the unmarked term in the gender opposition”. See García Negroni and Hall (2022), Stetie and Zunino (2022), and Vela-Plo and Ortega-Andrés (2025), for more information on the use of the non-binary neomorpheme “-e” in Spanish, and its use in comparison with other non-binary forms such as “x” or “@”. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | This study used the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: a standardised test that has been cross-culturally validated and measures hostile and benevolent sexism towards women (Glick & Fiske, 1996). Since the same test is used in the present study, more information on it can be found in Section 3.2. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Similar results have been found in experimental studies on French (Chatard et al., 2005; Brauer & Landry, 2008; Gygax et al., 2008, 2012; Vervecken et al., 2015) or German (Braun et al., 2005; Irmen, 2007; Stahlberg et al., 2007; Gygax & Gabriel, 2008; Sarrasin et al., 2012), confirming that the predominant interpretation of masculine forms is specific, and that generic interpretation are more difficult to obtain or appear in highly self-monitored speech (i.e., not in spontaneous sentence comprehension), which is hardly the most common mode. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | The results from the study in Khoroshahi (1989) revealed differences in the mental imagery connected to masculine forms or GFL strategies only in the case of women who had reformed their language (i.e., who used GFL strategies in English). The author concluded that the adoption of GFL was only effective if there is personal awareness of the discriminatory nature of some expressions and there is a personal commitment to change. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Precisely, in Stahlberg and Sczesny (2001), people with negative attitudes towards GFL did not differ in their reaction times when they evaluated whether an image of some person could be referred to in any of the language versions. But, interestingly, people with positive attitudes towards GFL reacted in different ways depending on the linguistic condition. In the masculine condition, it was harder for participants with a favorable attitude towards GFL to refer to a woman by means of a singular masculine noun, especially if the noun carried a male stereotype (e.g., politician). And, in the GFL condition with capital “I”, participants reacted more slowly to images of men than to images of women (no male bias). | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Social stereotypes have also been shown to influence gender perception; hence, experimental studies should either control for this variable or employ methodologies that assess the impact of stereotypes (as in Carreiras et al., 1996; Herrera Guevara & Reig Alamillo, 2020; or Anaya Ramírez, 2020, and Anaya Ramírez et al., 2022 for Spanish). For this reason, gender stereotypicality of the role described in our study has been controlled for. Moreover, effects of speaker age were found by Switzer (1990), who tested schoolchildren of two different age groups in English: the older age group (12–13 years) gave more mixed-gender interpretations of generic forms than the younger one (6–7 years). Switzer concludes that, with adolescence, speakers become (linguistically) more aware of the potential mixed-gender interpretations. See also note 30. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | After rejecting results from bots and duplicated participations, results included data from 908 Spanish native speakers from Spain (472 women, 413 men, 20 non-binary people, and 3 people who did not disclose information about their gender). Among them, 27 reported being transgender. Since binary gender of participants was a pivotal variable in our analyses, only results from participants who reported being either ciswomen or cismen were selected for further analysis (although all of them were offered compensation for their participation). Further data filtering was based on three control questions about the experimental text: only participants who answered correctly to at least two of the three simple comprehension questions were remunerated and included in the final pool for data analysis. A third step in data filtering consisted in rejecting results from participants who took longer than 10 min reading the experimental text or longer than 125 s responding in the picture selection task (showing that they were distracted during the task). | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | The distribution of the participants by their region of origin is the following: Andalucía, 220; Madrid, 201; Comunidad Valenciana, 76; Catalunya, 75; Galicia, 58; Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco, 50; Castilla y León, 45; Islas Canarias, 41; Murcia, 27; Castilla la Mancha, 26; Aragón, 24; Asturias, 21; Islas Baleares, 16; Extremadura, 10; Cantabria, 7; Navarra, 7; and La Rioja, 4. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | The condition in masculine has 216 words; the condition with split forms 226 words; the condition with unmarked gender expressions and epicenes 228 words; and the condition with neomorpheme “-e”, 215 words. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Norming methodology, materials and data are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/u3brc. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | These two points, adherence to the feminist movement and affinity with LGTBIQ+ communities, were not part of a standardised test, but assessed with three questions each (created by the authors) that can be found in the materials openly available in the OSF repository linked in the Data Availability Statement section. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | Our questionnaire included several exploratory questions on attitudes towards GFL strategies and masculine “generics”. For our purposes, only two statements that support GFL and two other statements showing resistance to GFL were chosen for evaluating whether participants had more of a positive or a negative attitude: (i) changing the language toward more inclusive language is very difficult and/or unnecessary (resistance, reverse-scored); (ii) using inclusive language is useless and ridiculous (resistance, reverse-scored); (iii) not using inclusive language and constantly employing the generic masculine excludes certain people and groups (support); (iv) we should use inclusive language so that the language reflects the changes we make in our society (support). | ||||||||||||||||||||