Reducing the Asymmetry of Theta-Assignment to Third-Factor Principles

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Duality of Semantics: only External Merge creates the θ-position, and the non-θ-position is created by Internal Merge1.

- (2)

- {EA, {v* {V, IA}}}

- (3)

2. θ-Assignment Under Minimal Search

2.1. Defining the Minimal Search for Theta-Assignment

- (4)

- MS = <SA, SD, ST>Search Algorithm (a slightly simplified version of Ke, 2024, p. 855):

- The Search probes into an SD to find the ST (a head) the search agent wants.

- Whenever the Search hits a head, it returns it to the search agent.

- When an ST is found and returned to the search agent, the search terminates.

- If an ST is not found after a run of a search, the search saves the more embedded set(s) in memory and sees it (them) as a new SD.

- If an ST is found in the more embedded set(s), the search terminates.

- If an ST is not found in the most embedded set(s), the search terminates.

- (5)

- {γ {α 1,2}, {β 3,4}}

- (6)

- Minimal Search-based θ-assignment = def. SA+ SD+ST, where

- (7)

- {the, boy}

2.2. R and v* Are Introduced via Separate External Set-Merge and Aggregated Eventually: The Standard Assumption

- (8)

- a. {R, IA}b. {IA {R, IA}}c. {v* {IA {R, IA}}}d. {EA {v* {IA {R, IA}}}}

- (9)

- a. He killed a whole day.b. He killed a beer.c. He killed a goat.

- (10)

- a. When the Battle of Cannae was lost, everything started to hit the fan.b. # When the Battle of Cannae was lost, the shit started to hit the wall.

2.3. R and v* Are Associated via External Merge

2.3.1. <R, v*> Are Formed via External Pair-Merge

- (11)

- a. {EA {<R, v*> {β IA {α R IA}}}} (R is a transitive verb)b. {EA {<R, v*> {β R {α C}}}} (R is a bridge verb)

- (12)

- {EA {β <R, v*> {α C}}}

- (13)

- {EA {α <RAgent, Theme, v*>, IA}}

2.3.2. {R, v*} Are Formed via External Set-Merge

- (14)

- {EA {{R, v*} IA}}

- (15)

- {RAgent/Theme v*}

- (16)

- {EA {{RAgent/Theme v*}, IA}}}

- (17)

- {IA, {{RAgent/Theme v*}, IA}}

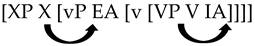

2.4. R and v* Stay Separate: Does MS-TH Suffice to Enable θ-Assignment While Capturing the Asymmetry?

- (18)

- {EA {v* {R, IA}}}

3. θ-Assignment Under PIC and Preservation

θ-Interpretation Is a Relation: Assigner and Assignee Are Transferred Together

- (19)

- {v*{R, IA}}}

- (20)

- {v*{IA {R, IA}}}

- (21)

- {C {EA {v* {IA, {R, IA}}}}}27

- (22)

- {C {EA, {v* {{R, IA}}}

- (23)

a. Hanako-ga saihu-o nakusi-ta kyositu. Hanako-NOM purse-ACC lose-PAST classroom “The classroom where Hanako lost her purse.” b. *Hanako-no saihu-o nakusita kyositu. Hanako-GEN purse-ACC lose-PAST classroom “The classroom where Hanako lost her purse.”

- (24)

a. Zhangsan mai-le shu. Zhangsan bought book “Zhangsan has bought a book.” b. Zhangsan shu mai-le. Zhangsan book bought “Zhangsan has bought a book.”

- (25)

- {EA {v* {IA, {R, IA}}}}

- (26)

- a. *{IA {v* {IA {R, IA }}}} > *the man sees (intended: the man sees himself)b. *{EA{v*matrix{EA{C {EA{v* {IA {R, IA}}}}}}}} > *Johni thinks Johni hit Maryc. ?{v* {EA{IA {R, IA}}}}

4. Conclusions

- (27)

- ?{v* {EA{IA {R, IA}}}}

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | As pointed out by an anonymous referee, it should be noted that the definition of the Duality of Semantics presented here is distinct from the previous one in Chomsky (2020, UCLA lectures), according to which External Merge only creates argument structures while Internal Merge only generates discourse-oriented/information-related and scopal properties. It should also be clarified that although the Duality of Semantics is conditioned by Preservation, it is a language-specific condition while Preservation is a general principle of computation (i.e., third-factor). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Note that the asymmetric Spec–Head vs. Head–Complement θ-assignment is neatly resolved under Funakoshi’s feature-valuation system, while, as an anonymous referee points out, the c-command relations are still asymmetric in terms of set-formation: X c-commands terms of sister; V c-commands sister. In the remainder of this paper, I will demonstrate that such asymmetry can be accommodated in accordance with third-factor-compliant operations. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | On the elimination of feature-valuation in narrow syntax, see Epstein et al. (2022a). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Besides the violation of MY, Parallel Merge also suffers from the problem of complicating the simplest Merge. For Parallel Merge to take place, it must be equipped with the function of probing into the formerly formed set to decide on its target. One may claim this can be achieved by Minimal Search, but Minimal Search would always detect the two sets and mark them as proper candidates for further Merge at its first application, yielding normal External Merged output. In addition to the violation of MY, Narita and Fukui (2022, p. 271) also reject the notion of Parallel Merge as it causes asymmetry in terms of in-domain-of relation and assigns additional information to the simplest set-theoretic operation Merge (i.e., there is another mother set). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | There are many different interpretations of SMT, and in this paper, I construe SMT as being that the Simplest Merge is the only operation necessary and it must be in the simplest form. In other words, no additional narrow syntax operations are presumed (cf. Chomsky, 2000, 2004). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | One may wonder how an argument, a set per se, can serve as the target of MS. Recall that the ST is assumed to be a head according to the definition of SA in (4). It is likely that the definition presented in (6) would be technically more precise if the term argument is replaced with the D or N head of an argument. The only reason I have chosen the present form of the definition utilizing simpler terminology is that no difference is evident regarding empirical consequences. Whether the ST returned by MS-TH is an argument (a set) or the head of an argument, the correct θ-relation can be obtained. For example, MS-TH would yield the expected output whether {R, {IA}} or {R, {IA Head, XP}} is the SD. In the case of {R, {IA}}, the two parallel searches find R and IA in one run of MS-TH, while in the case of {R, {IA Head, XP}}, one more application of MS-TH is required. Crucially, nothing blocks the search from finding the two targets in a minimal way. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | An anonymous referee notes that there are two possible approaches regarding what constitutes the STs. In the first approach, each search targets either a predicate or an argument, requiring at least two searches to locate all the STs. Thus, STs are more precisely defined as “a predicate OR an argument”. In the second approach, each search is assigned with two targets, namely “a predicate AND an argument”, suggesting the search does not terminate upon finding one of the STs. At first glance, the two approaches appear equally viable for θ-role assignment, though the second might reduce computational load by avoiding intermediate search termination. However, the first approach offers a critical advantage: because each search has only one target, it imposes less memory burden on the search agent (in the second approach, the search agent must retain partial results—e.g., a located argument—while being dedicated to the continued search for the predicate, increasing working memory demands). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | In Omune (2020) and Narita and Fukui (2022), among many others, pair-Merge is better eliminated. It is not compatible with the cyclicity nature of Merge and necessarily violates the no-tampering condition. As will be discussed later, pair-Merge in the following subsections circumvents such conceptual problems. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | This amounts to saying that Spec, RP may be the position where one of the two objects of a ditransitive verb receives its θ-role, because it would externally merge to this position. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | An anonymous referee also suggests that CI would filter out the same results if IA and R have already been returned by MS. Following that, assigning a role to the higher copy of IA not only violates Theta Theory but also introduces redundancy. Alternatively, if the STs of MS-TH are defined as “an Externally Merged predicate and/or an Externally Merged argument”—subject to the Duality of Semantics—then MS-TH will always ignore the higher copy of IA. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | If we assume a transitive R takes on the responsibility to assign θ-roles to both EA and IA, MS-TH can nonetheless produce the warranted result. Since v* is no longer a part of the ST, when the left-branching search hits it, CI would know that all it needs is on the right side. With one of its roles passed to IA, R remains active after the external merger of EA. The MS-TH would find EA and R in three applications, which is somewhat costlier compared to the search locating R and IA. This may also account for the fact that IA is more closely related to the verb than EA. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | At this point, I am not entirely sure what empirical consequences this derivation may yield. In Section 3, where a distinct Transfer-based θ-assignment system is introduced, derivations in such forms are also allowed. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | An anonymous referee denotes the issue that the specific θ-role of EA is also dependent on the {R, IA} complex (as in he broke his leg vs. he broke his word), which seems to suggest a set formed via merge is more than just a set. Unfortunately, I do not have a definite answer to this issue as to how the MS-TH-based framework can offer a reasoning. A conjecture is that what kind of θ-role v* bears is contingent upon {R, IA}; what enables such interpretive dependency might also be Minimal Search: after R and IA merge, the real meaning of the verbs is determined by MS (in this case, such MS may be classified as another kind of MS on par with MS-Agree/Labeling/Theta), and then the MS applies again to locate v* and R (with its meaning specified), where the θ-role of v* is determined. One may wonder whether this conjecture faces the problem of changing the interpretation of v* in the derivation (as will be discussed below, alternative modes of merge seem to be free from such a problem, because the amalgamation of R and v*, as well as the specification of the role v* bears, are complete before entering into syntax). Crucially, as such a semantic specification is argued to be exclusively carried out by MS, only CI, rather than syntax, would detect that a change in interpretation has happened. Consequently, v*’s interpretation remains unchanged in the course of narrow syntax derivation. Another strong hypothesis is that R is equipped with all θ-roles of a verb and v* is merely a semantically vacant categorizer. See footnote 9 for a related discussion. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | In fact, if the present proposal that the θ-assigning MS applies as soon as both the assigner and assignee are entered into the computation is feasible, EA can never receive a θ-role from R because MS would always locate EA and v* right after the External Merge of EA. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | It is reasonable to claim that the pair-Merge of R and v* in fact does not change their interpretation, because they remain as predicates throughout the derivation. Here I adopt the notion of Stability formulated in Epstein et al. (2022c) which dictates that an SO cannot change its interpretation or status in the course of derivation. Therefore, the pair-Merge of R and v* within the syntax should be undesirable as R’s category is determined in the derivation, a change of status. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | An anonymous referee points out that the reunion of R and v* amounts to saying that object shift does not occur, which would face severe problems regarding labeling in cases like ECM constructions. Although the Transfer-based approach in Section (θ-Interpretation Is a Relation: Assigner and Assignee Are Transferred Together) claims that object shift occurs in English, the MS-based approach discussed here leaves this issue untouched. The MS-based approach does not depend on the assumption that there is no object shift. One possible derivation is that the OBJ of ECM matrix verb such as believe first internally merges to [Spec, <Rbelieve, v*>] for labeling via phi-agreement. The <Rbelieve, v*> amalgam furthers merges to the left of OBJ to maintain the correct word order, as illustrated in (iia–b).

The further merge of <Rbelieve, v*> seems to be warranted by the fact that the EA, which also takes part in the phi-agreement, can undergo further movement as in (iii).

Narita and Fukui (2022, p. 205) employ an alternative approach, in which v* and R are also presumed to be joined externally, to capture the essential facts about ECM constructions. Simply put, they propose the entire infinitival clause (including the EA) would internally merge to a position where EA and <Rbelieve, v*> are equally prominent; hence, phi-labeling (dubbed as Feature equilibrium by them) becomes possible. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | The EpM approach proposed in Epstein et al. (2022b) is an operation dedicated to bridge verb construction, as the invisible uninterpretable φ on v* hinders Case-checking. However, the structure in (13) does not face any labeling problem because MS would find the most prominent element (i.e., <R, v*>) in the syntactic object, and α is simply labeled <R, v*>. Case-checking/valuation, according to Epstein et al. (2022a, p. 113), is more of a morpho-phonological component, which does not have a place in narrow syntax. Thus, I conclude that because (13) does not cause any narrow-syntax/CI impairment, EpM can apply to transitive verbs, and IA-shifting does not occur. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | The inheritance of the to-be-assigned-θ-role is not a novel creation. In Grimshaw and Mester (1988), θ-marking capacity is assumed to be transferable between predicates. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | As noted by Saito (2013), such compound lexical verbs are readily argued to be formed in the lexicon and projected into a single VP by Kageyama (1993). A question then arises regarding the current theoretical considerations: how do we rule out the possibility that the two verbal heads are joined via EpM? I propose that, following Saito’s generalization that claims lexical compound verbs must meet the selectional requirements of both participant verbal heads, illustrated in (iva-b). In (ivb), the compound verb comprises unaccusative and transitive components, falling outside the generalization.

EpM-created lexical compound verbs fail to meet this condition. Given the definition of pair-Merge, an ordered set would be formed, suggesting that there is an internal hierarchy within the set. If Japanese compound verbs were formed via EpM, the selectional requirement imposed on, for example, a v*-head that s-selects transitive/unergative V would be immediately satisfied once it locates the hierarchically higher V; thus, the identification of both participant Vs may not be attainable. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | One might argue that the presyntactic inheritance does not have to take place if we assume the transfer postpones until IA is merged into the system, where it receives Theme from R by MS. The postponed transfer, following Obata et al.’s (2015) Underspecified Operation Ordering, seems reasonable. However, such an assumption has one potential theoretical disadvantage. If the transfer of R can wait, then the derivation would look like (v) after the merger of IA:

Say MS applies to (v). It would locate three terms in parallel: R, v*, and IAH. As they are in the identical depth, another implicit interpretational operation, Compare (see Shim, 2018), is required to determine the right assigner (i.e., R, for the IA). Such an operation will be executed once more for the same reason if the transfer further waits for the merger of EA. Thus, the postponed transfer necessarily leads to a greater computational burden. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | An anonymous referee points out that the phasehood of v* does not disappear after the inheritance. I maintain the standard assumption that v* can also have its complement, i.e., R transferred upon the formation of {R, v*}, and my proposal does not rule out such a possibility. However, if RAgent/Theme is the one transferred, arguments would never be θ-marked. In other words, v* and R can have each other transferred by theory, whereas only when v* is transferred does the proper θ-marking become possible. The inheritance of θ-role from v* to R may have the same motivation: as either v*Agent or RTheme is transferred, there would be an argument to remain θ-less. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | Again, the asymmetry in terms of how much it would take to find both STs remains the same whether the head of the argument or the argument itself is an ST. For instance, we need two runs of MS-TH to find {R, v*} and the head of IA, whereas three runs of MS-TH are required to find the head of EA and {R, v*}, as in the structure of {{EAH, XP} {{R Agent/Theme v*}, {IAH, XP}}}. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | It should be kept in mind that, as an anonymous referee points out, it is only Assignment as a syntactic operation that is dispensed under the current framework. In fact, the assignment of roles would still have to take place in semantic components. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | The terms assigner and assignee used here are for expository purposes. As the operation Assignment is discarded in this proposal, assigner should be construed as the predicate with the θ-role, while assignee is the nominal element without one. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 | One may claim that PIC only prohibits what has been transferred to be targeted by further syntactic operations, and CI could still locate the assigner and assignee, disregarding which one is transferred first. As suggested in Saito (2021, p. 161), PIC also intervenes in a nonsyntactic operation like Form Copy. I argue this may be attributed to a principle normal for neural systems: Resource Restriction (see Fong, 2021, p. 3). In a nutshell, it holds that human brains easily forget. In the case of θ-interpretation, once CI, whose current goal is to construct a θ-relation, sees the IA without a predicate, it would wait for the completion of the next transfer output, in which CI again aims to build a θ-relation, instead of bearing this IA in memory. As pointed out by an anonymous referee, IA should not be “forgotten” as the meaning of the verb actually rests on it. Note that my argument regarding Resource Restriction does not take IA to be an object that can be ignored in CI. Instead, since CI searches into each transfer output to construct a θ-relation, if there is no such a relation to be constructed, CI simply moves on. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | An anonymous referee wonders how the current proposal can deal with the data of object wh-movement illustrated in (vi).

Specifically, since believe and who2 are in the same transfer domain, how do we block the θ-relation between believe and who2? Within the transfer domain in question, what CI actually sees is the two members of a set, namely, BELIEVE, the root and {who2 {that {Mary hit who1}}}. Since a propositional CP is taken to be the proper θ-assignee of bridge verbs such as believe, the θ-interpretation is accessible at this point. Hence, unless assumed otherwise, there is no motivation for CI to go one step further to locate who2 as the assignee (in fact, who2 is the copy of an argument that has been a part of a distinct θ-relation; CI cannot repetitively interpret who2 with respect to θ), which is reminiscent of the MS-based approach articulated in Section 2, as it minimizes computational effort by locating BELIEVE and its CP-complement rather than a member within the complement. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27 | An anonymous referee wonders how I treat INFL in such a derivation. Let us take a look at the case where the phasehood is inherited by INFL. Although the complement of INFL has now become the second transfer domain, EA and v* are still transferred together. EA may further be raised to Spec, INFL, where the higher copy of EA and INFL are in the transfer domain. Notice that INFL does not have a to-be-discharged θ-role; hence, no additional θ-role would be added to the EA. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 | See footnote 30 for a discussion on the case in which multiple arguments and one predicate are in the same transfer domain. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | An anonymous referee wonders how the θ-relation would be constructed if EA is merged, as in (viia). Since EA and the higher copy of IA are in the same transfer domain with v*, the EA can also be chosen as the receiver of the Agent-role.

If we do not assume a selective device that appoints the candidates to a θ-relation, a violation of univocality would always be expected, because there is only one predicate to two arguments. To obtain the correct output, CI may employ Minimal Search to find the most effortless way to construct a θ-relation, and the IA with a θ-role, instead of the EA, in (viia) as the target to be sent to CI for θ-interpretation. By contrast, a structure like (viib) does not pose any problem: the higher copy of IA does not compete for a position in the Agent-interpretation because the EA is structurally closer to the predicate v*. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Baker, M. (1988). Incorporation: A theory of grammatical function changing. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bošković, Ž., & Takahashi, D. (1998). Scrambling and last resort. Linguistic Inquiry, 29, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branan, K., & Erlewine, M. Y. (n.d.). Locality and (minimal) search. In K. K. Grohmann, & E. Leivada (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of minimalism. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (1981). On the representation of form and function. The Linguistic Review, 1(1), 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, N. (1993). A minimalist program for linguistic theory. In K. L. Hale, & S. J. Keyser (Eds.), The view from building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of sylvain bromberger. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (1995). The minimalist program. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (2000). Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In R. Martin, D. Michaels, & J. Uriagereka (Eds.), Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of howard lasnik (pp. 89–155). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (2004). Beyond explanatory adequacy. In A. Belletti (Ed.), Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures (pp. 104–131). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (2005). Three Factors in Language Design. Linguistic Inquiry, 36, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, N. (2008). On phases. In R. Freidin, C. Otero, & M. L. Zubizarreta (Eds.), Foundational issues in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of jean-roger vergnaud (pp. 133–166). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (2013). Problems of projection. Lingua, 130, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, N. (2015). Problems of projection: Extensions. In E. DiDomenico, C. Hamann, & S. Matteini (Eds.), Structures, strategies and beyond: Studies in honour of adriana belletti (pp. 3–16). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (2020). The UCLA lectures: With an introduction by Bob Freidin. LingBuzz. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (2021). Minimalism: Where are we now, and where can we hope to go. Gengo Kenkyu, 160, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N., Seely, T. D., Berwick, R. C., Fong, S., Huybregts, M. A. C., Kitahara, H., McInnerney, A., & Sugimoto, Y. (2023). Merge and the strong minimalist thesis. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Citko, B. (2008). Missing labels. Lingua, 118, 907–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S. D. (1998). Overt scope marking and covert verb second. Linguistic Inquiry, 29, 181–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S. D., Kitahara, H., & Seely, T. D. (2015). From Aspects ‘daughterless mothers’ (aka delta nodes) to POP’s ‘motherless’-set (aka non-projection): A selective history of the evolution of simplest merge. In Á. Gallego, & D. Ott (Eds.), 50 years later: Reflections on chomsky’s aspects (pp. 99–112). MITWPL Aspects volume. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, S. D., Kitahara, H., & Seely, T. D. (2022a). A simpler solution to two problems revealed about the composite-operation agree. In A minimalist theory of simplest merge. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, S. D., Kitahara, H., & Seely, T. D. (2022b). Phase cancellation by external pair-merge. In A minimalist theory of simplest merge. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, S. D., Kitahara, H., & Seely, T. D. (2022c). Some concepts and consequences of 3rd factor-compliant simplest MERGE. In A minimalist theory of simplest merge. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, S. (2021). Some third factor limits on merge. Manuscript. University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi, K. (2009). Theta-marking via Agree. English Linguistics, 26(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimshaw, J., & Mester, A. (1988). Light verbs and θ-marking. Linguistic Inquiry, 19, 205–232. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, N. (2020). Labeling without weak heads. Syntax, 23(3), 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornstein, N. (1999). Movement and control. Linguistic Inquiry, 30, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. (1991). Object positions. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 9, 577–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, T. (1993). Grammar and word formation. Hituji Syobo. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ke, A. H. (2024). Can agree and labeling be reduced to minimal search? Linguistic Inquiry, 55(4), 849–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, M. (1995). Phrase structure in minimalist syntax [Doctoral dissertation, MIT]. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, A. (1984). On the nature of grammatical relations. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Narita, H., & Fukui, N. (2022). Symmetrizing syntax. merge, minimality, and equilibria. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Obata, M., Epstein, S. D., & Baptista, M. (2015). Can crosslinguistically variant grammars be formally identical?: Third factor underspecification and the possible elimination of parameters of UG. Lingua, 156, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, M. (2004). Ga-no conversion and overt object shift in Japanese. Nanzan Linguistics, 2, 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Omune, J. (2020). Reformulating pair-merge, inheritance and valuation [Doctoral dissertation, Kansai Gaidai University]. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y. (1994). Object noun phrase dislocation in mandarin Chinese [University of British Columbia dissertation, University of British Columbia]. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, M. (2013). Conditions on Japanese phrase structure: From morphology to pragmatics. Nanzan Linguistics, 9, 119–145. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, M. (2021). Two notes on copy formation. Nanzan Linguistics, 17, 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J.-Y. (2018). <φ, φ>-less labeling. Language Research, 54(1), 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.-Y., & Epstein, D. S. (2015). Two notes on possible approaches to the unification of theta relations. Linguistic Analysis, 40, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shyu, S. (2001). Remarks on object movement in mandarin SOV order. Language and Linguistics, 2(1), 93–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N. (2000). Object shift in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 28(2), 201–246. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, T. Reducing the Asymmetry of Theta-Assignment to Third-Factor Principles. Languages 2025, 10, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080176

Xie T. Reducing the Asymmetry of Theta-Assignment to Third-Factor Principles. Languages. 2025; 10(8):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080176

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Tao. 2025. "Reducing the Asymmetry of Theta-Assignment to Third-Factor Principles" Languages 10, no. 8: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080176

APA StyleXie, T. (2025). Reducing the Asymmetry of Theta-Assignment to Third-Factor Principles. Languages, 10(8), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080176