5.1. Distribution of Negators in the 17th-Century Translation

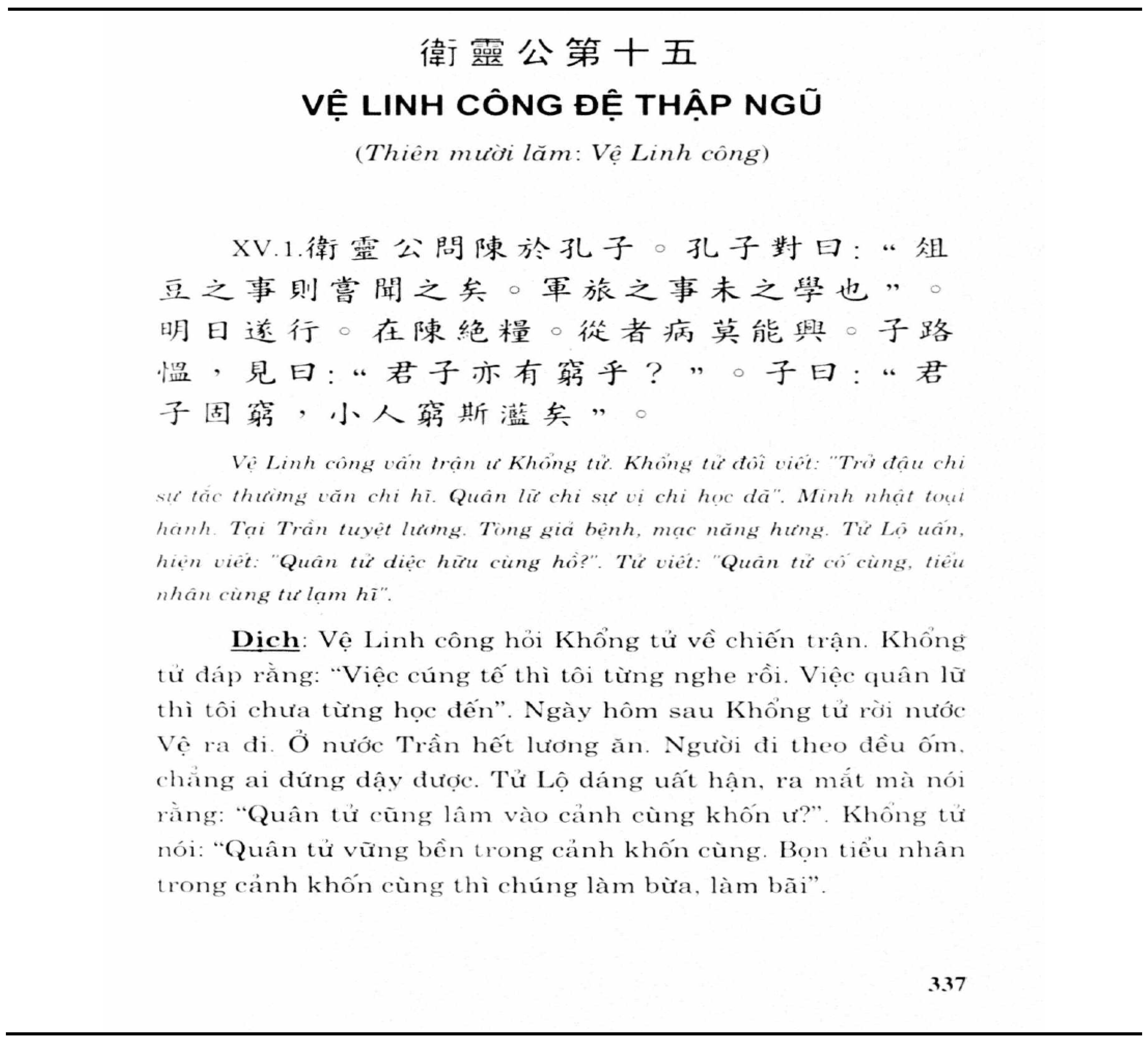

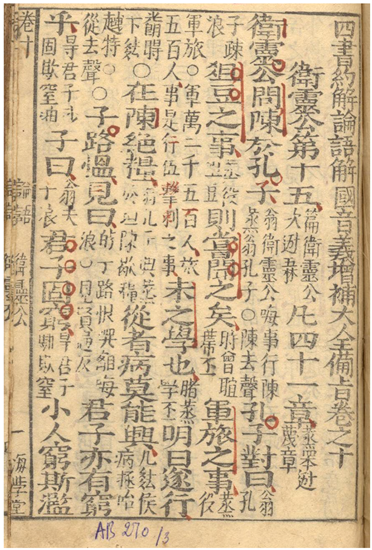

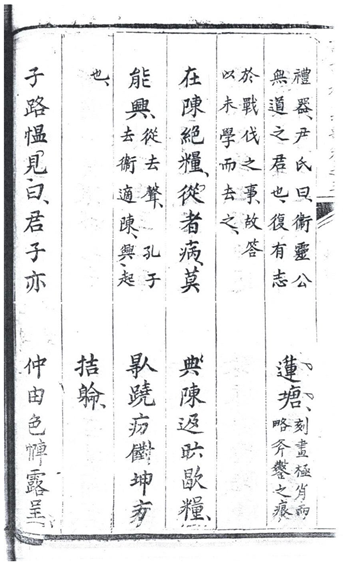

Our analysis shows that in the 17th-century Vietnamese translation of the

Analects, most instances of 不

bù, 無

wú, and 非

fēi were translated using

chẳng, the native Vietnamese negator. Specifically,

chẳng was used in 152 out of 153 cases of

bù, 32 out of 38 cases of

wú, and all 4 instances of

fēi, as seen in

Table 6. This overwhelming reliance on

chẳng reflects a clear preference for native sentential negation over the adoption of Sino-Vietnamese lexical prefixes like

bất,

vô, or

phi, which do not appear in the translation at all.

In the original Literary Sinitic text, 不

bù is used 153 times; 152 of these instances were translated using the native Vietnamese negator

chẳng.

| (20) | bù (不) | => | chẳng | | |

| a. | Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.21) |

| | 君子 | 矜 | 而 | 不 | 爭、 |

| | Quân tử | căng | nhi | bất | tranh. |

| | gentleman | proud | but | NEG | contentious |

| | 群 | 而 | 不 | 黨、 | |

| | Quần | nhi | bất | đảng”. | |

| | join | but | NEG | cliquish | |

‘The gentleman is proud but not contentious. He joins with others but is not cliquish.’

| b. | Vietnamese translation (17th century) |

| | 㝵 | 君子 | 嚴 | 麻 | 拯 | 爭 |

| | Người | quân tử | nghiêm | mà | chẳng | tranh |

| | CLF | gentleman | proud | but | NEG | contentious |

| | ‘The gentleman is proud but not contentious’. |

| | 固 | 排 | 麻 | 拯 | 覓 | ![Languages 10 00146 i005]() | 𤿤 | 丕 | |

| | Có | bầy | mà | chẳng | mếch | làm | bè | vậy | |

| | has | group | but | NEG | wrongly | make | ally | PRT | |

| | ‘He joins with others but is not cliquish’. |

無

wú is used 38 times in the original Chinese text, and it is typically translated as

chẳng or

chẳng có ‘not have’ in the Vietnamese translation.

| (21) | 無wú => chẳng có ‘not have’ |

| a. | Literary Sinitic (Chapter 17.23) |

| | 君子 | 有 | 勇 | 而 | 無 | 義 |

| | Quân tử | hữu | dũng | nhi | vô | nghĩa |

| | gentleman | possess | courage | but | lack | rightness |

‘A gentleman who possesses courage but lacks rightness’.

| b. | Vietnamese translation (17th century) |

| | 㝵 | 君子 | 固 | 孟 | 麻 | 拯 | 固 | 義 |

| | Người | quân tử | có | mạnh | mà | chẳng | có | nghĩa |

| | gentleman | have | courage | but | not | have | rightness |

‘A gentleman who possesses courage but lacks rightness’.

Here, 無 vô is rendered as chẳng có, indicating the absence of a quality (rightness). This structure mirrors the negation pattern found in Chinese but uses the native Vietnamese negator chẳng có instead of vô.

非

fēi, which appears four times in the original Chinese text, is mostly translated as

chẳng phải ‘not right’ in the Vietnamese translation, a construction that aligns with (verbless) nominal negation in Vietnamese.

| (22) | 非 fēi => chẳng phải ‘not right’ |

| | a. | Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.28) |

| | | 人 | 能 | 弘 | 道、 | 非 | 道 | 弘 | 人、 |

| | | Nhân | năng | hoằng | đạo, | phi | đạo | hoằng | nhân |

| | | Person | can | enlarge | Way, | NEG | Way | enlarge | person |

‘A person can enlarge the Way; it is not the case that the Way can enlarge a person’.

| | b. | Vietnamese translation (17th century) |

| | 𠊛 | 咍 | ![Languages 10 00146 i006]() | 𢌌 | 道, | 拯 | 沛 | 道 | 咍 | ![Languages 10 00146 i007]() |

| | Người | hay | làm | rộng | đạo, | chẳng | phải | đạo | hay | làm |

| | person | can | do | large | Way | not | right | Way | can | do |

| | 𢌌 | 㝵 | | | | | | | | |

| | rộng | người | | | | | | | | |

| | large | person | | | | | | | | |

‘A person can enlarge the Way; it is not the case that the Way can enlarge a person’.

The 17th-century Vietnamese translation of the Analects preserved the semantic distinctions of the Literary Sinitic negators through native syntactic mean; we do not see examples of prefixation (lexical negation) yet in the Vietnamese text. For example, the complex form chẳng có ‘not have’ (a negator and an existential verb) was used for existential negation and chẳng phải ‘not right’ (a negator and a predicate) was used for (verbless) nominal negation. Chinese syntactic negators, therefore, are consistently rendered using native Vietnamese syntactic negators—a significant observation, as later translations show the gradual emergence of Sino-Vietnamese negators.

This dominance of native Vietnamese negators during the 17th century points to a period where Vietnamese largely retained its own negation system, even as it borrowed Chinese vocabulary in other lexical domains. The findings illustrate the selective nature of linguistic adaptation, where core grammatical elements like negation were slower to absorb Sino-Vietnamese influences. In the following section, we turn to the 19th-century translation of the Analects, examining how the prefixes bất, vô, and phi began to be integrated into the Vietnamese language while continuing to coexist with native negators such as chẳng.

5.2. Distribution of Negators in the 19th-Century Translation

The data for the 19th-century translation reveal a mix of native and borrowed negators, as illustrated in

Table 7:

In the 19th-century Vietnamese translation of the

Analects, we observe a more diverse distribution of negators compared to the 17th-century text. Native negators like

chẳng continue to be dominant, appearing 90 times to translate 不

bù and 11 times to translate 無

wú, but we also see the increasing use of

không, which appears 35 times to translate 不

bù and 14 times to translate 無

wú. This shift aligns with the historical trend of

không, which is derived from Chinese 空

kōng, becoming more integrated into the Vietnamese language, particularly as a sentential negator. Recent studies have noted that

không began to grammaticalize into a general negator in the late 17th century (

Phan et al., 2024), and by the late 19th century, it started to rival or even replace

chẳng as the dominant negator (

Trinh et al., 2024).

Additionally, we observe that, among the three prefixes, bất is the first to appear in the Vietnamese translation, albeit in just two instances. Its early inclusion marks the initial stage of the integration of Sino-Vietnamese prefixes into Vietnamese negation. This reflects a gradual linguistic shift, where native negators like chẳng still dominated but were slowly accompanied by borrowed Sino-Vietnamese elements. The appearance of bất signals the beginning of increased lexical borrowing from Chinese, which would become more prominent in subsequent periods.

In the 19th-century translation, 不

bù is predominantly translated as sentential negators

chẳng or

không.

| (23) | 不 bù => chẳng/không |

| a. | Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.21) |

| | 君子 | 矜 | 而 | 不 | 爭、 |

| | Quân tử | căng | nhi | bất | tranh. |

| | gentleman | proud | but | NEG | contentious |

| | 群 | 而 | 不 | 黨、 | |

| | Quần | nhi | bất | đảng”. | |

| | join | but | NEG | cliquish | |

‘The gentleman is proud but not contentious. He joins with others but is not cliquish’.

| b. | Vietnamese translation (19th century) |

| | 𠊛 | 賢 | 嚴 | 吏 | 空 | 争、 | | |

| | Người | hiền | nghiêm | lại | không | tranh, | | |

| | person | gentle | proud | but | NEG | contentious | | |

| | 和 | 𢧚 | 𢛨 | 眾 | 拯 | 𠴇 | 誽 | 隊𡿨、 |

| | Hoà | nên | ưa | chúng | chẳng | bênh | dua | đòi, |

| | join | then | like | group | NEG | incline to | cliquish | |

‘The gentleman is proud but not contentious. He joins with others but is not cliquish’.

Having compared example (20) and example (23), we see that in the same Literary Sinitic sentence, 不 bù appeared twice and was translated as chẳng in both instances in the 17th-century translation, whereas in the 19th-century translation, one instance was rendered as chẳng and the other as không. The shift from the native sentential negator chẳng to the Chinese-derived sentential negator không suggests an increased adoption of Sino-Vietnamese lexical elements during the 19th century, although the chosen item does not match Chinese usage.

Another distinctive feature of the 19th-century translation, among the three bilingual texts under investigation, is the first appearance of one of the three Sino-Vietnamese prefixes. This is the earliest text where 不

bù is translated as

bất, marking the initial stage of integrating these items into Vietnamese negation.

| (24) | 不 bù => bất |

| a. | Literary Sinitic (Chapter 19.3) |

| | 嘉 | 善 | 而 | 矜 | 不 | 能 |

| | gia | thiện | nhi | căng | bất | năng |

| | applaud | good | but | sympathize | NEG | ability |

‘He applauds good men and sympathizes with those who lack ability’.

| b. | Vietnamese translation (19th century) |

| | 𠸦 | 𠊛 | 唯𡿨 | 卒 | 傷 | 台 | 不 | 才 |

| | Khen | người | giỏi | tốt | thương | thay | bất | tài |

| | applaud | person | good | nice | sympathize | PRT | unable | |

‘He applauds good men and sympathizes with those who lack ability’.

| (25) | 不 bù => bất |

| a. | Literary Sinitic (Chapter 17.21) |

| | 子 | 曰、 | 予 | 之 | 不 | 仁 | 也 |

| | Tử | viết: | “Dư | chi | bất | nhân | dã |

| | Confucius | say | Yu | PRT | no | human | PRT |

‘The Master said, Yu (Zai Wo) has no humaneness!’

| b. | Vietnamese translation (19th century) |

| | 𠰺 | 浪 | 予 | 意𡿨 | 罕 | 時 | 不 | 仁 |

| | Dạy | rằng | Dư | ấy | hẳn | thì | bất | nhân |

| | teach | that | Dư | that | clearly | TOP | unhuman | |

‘The Master said, Yu (Zai Wo) has no humaneness!’

Interestingly, these two examples where 不

bù is translated as

bất reveal distinct translation strategies: one slightly more innovative, and the other more conservative. In the first example (24), 不能

bù néng, which means ‘lacking ability’ in Literary Sinitic, is translated as

bất tài in Vietnamese. While

bất tài can still be understood as ‘lacking ability,’ it typically carries a stronger connotation of ‘incompetence’ or ‘lack of talent.’ This translation reflects a minor shift toward a more specific interpretation. In the second example (25), 不仁

bù rén, meaning ‘inhumane’ or ‘lacking benevolence,’ is translated as

bất nhân, which is a direct and faithful reflection of the original. Here, the translator adheres closely to the source text, preserving the core meaning of the Confucian concept of 仁

rén, or ‘benevolence’ (

Ivanhoe, 2000). Unlike the slight shift seen in the previous example, this translation remains conservative, ensuring that key philosophical terms retain their original sense and integrity. These two examples illustrate the early stages of the integration of

bất into Vietnamese negation. In one case, as with

bất tài, the translator makes subtle adjustments to fit Vietnamese usage, while in another, such as

bất nhân, the original term is maintained. Together, these cases suggest that the appearance of

bất in the 19th-century translation marks a gradual yet careful adoption of Sino-Vietnamese prefixes into the Vietnamese lexicon.

Similar to 不

bù, the negator 無

wú continues to be predominantly translated as

chẳng (11 times) or

không (14 times). However, we observe a more frequent use of

không as the preferred translation for

vô, reinforcing the trend of increased Sino-Vietnamese lexical borrowing in this period. This is consistent with recent studies on the grammaticalization path of

không (

Phan et al., 2024), which suggest that, before

không assumed the role of a general negator in Vietnamese, it initially functioned as an existential negator meaning ‘not have’. In the following example from Chapter 17.23 of the

Analects, 無

wú is translated as

không, reinforcing this trend:

| (26) | 無 wú => không |

| a. | Literary Sinitic (Chapter 17.23) |

| | 君子 | 有 | 勇 | 而 | 無 | 義 | 爲 | 亂 |

| | quân tử | hữu | dũng | nhi | vô | nghĩa. | vi | loạn |

| | gentleman | have | courage | but | NEG | rightness | do | rebellious |

‘A gentleman who possesses courage but lacks rightness will become rebellious’.

| b. | Vietnamese translation (19th century) |

| | 勇 | 麻 | 空 | 義 | 亂 | 𨢟 | 苦𡿨而 | 之 |

| | Dũng | mà | không | nghĩa | loàn | gây | khó | gì |

| | courage | but | NEG | rightness | rebellious | cause | trouble | thing |

‘A gentleman who possesses courage but lacks rightness will become rebellious’.

In the case of 非

fēi, the 19th-century translation shows a variety of renderings, including

chưa ‘not yet’,

lầm ‘wrong’, and

nào có ‘not have’, depending on the context.

| (27) | 非 fei => nào có ‘not have’ |

| a. | Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.28) |

| | 人 | 能 | 弘 | 道、 | 非 | 道 | 弘 | 人、 |

| | Nhân | năng | hoằng | đạo, | phi | đạo | hoằng | nhân |

| | Person | can | enlarge | Way, | NEG | Way | enlarge | person |

‘A person can enlarge the Way; it is not the case that the Way can enlarge a person’.

| b. | Vietnamese translation (19th century) |

| | 𠊛 | 咍 | 𩦓 | 𢌌 | 道 | 常、 | | |

| | Người | hay | mở | rộng | đạo | thường, | | |

| | person | can | open | large | Way | often | | |

| | 道 | 箕 | 芾 | 固 | 𩦓 | 芒 | 鄧 | 𠊛、 |

| | Đạo | kia | nào | có | mở | mang | đặng | người, |

| | Way | DEM | not | have | open | PRT | can | person |

‘A person can enlarge the Way; but the Way cannot enlarge a person’.

This variability may be influenced by the poetic nature of the text, which often allows for broader interpretation. The translator’s approach to 非 fēi seems more flexible, moving away from a strict adherence to uniform translation norms. This flexibility may reflect their efforts to convey the nuances of meaning and context, using different forms of negation depending on the specific situation.

Compared to the 17th-century translation, where the native sentential negator

chẳng was overwhelmingly dominant and there was no sign of

bất,

vô, or

phi, the 19th-century translation marks a transitional phase. A notable difference is the increased use of the Chinese-derived sentential negator

không, especially in translating both 不

bù and 無

wú. This shift aligns with recent research on the development of

không, which transitioned from an existential negator to a general negator (

Phan et al., 2024). Additionally, the 19th-century translation introduces

bất for the first time, signaling the early stages of integrating Sino-Vietnamese prefixes into the negation system.

Overall, the 19th-century translation reflects a period of transition in Vietnamese negation. Native negators like chẳng remained prominent, but the increasing use of không and the introduction of bất are indicative of a gradual integration of Sino-Vietnamese elements. In the following section, we explore the 21st-century translation of the Analects and how bất, vô, and phi have become more integrated into modern Vietnamese.

5.3. Distribution of Negators in the 21st-Century Translation

In contrast to earlier translations, the 21st-century version reflects a linguistic shift toward the frequent use of the Chinese derived không as the standard negator over the native Vietnamese chẳng.

As seen in

Table 8,

không has become the overwhelmingly preferred negator, translating 127 out of 153 instances of 不

bù, 27 out of 38 instances of 無

wú, and all 4 instances of 非

fēi. In comparison,

chẳng plays a more limited role in this period, appearing in only 12 instances for 不

bù and 2 for 無

wú, a stark contrast with its prominence in earlier translations. This decline reflects a shift in usage patterns where

không takes precedence, pushing

chẳng into a more emphatic or non-standard role. This supports previous research on the grammaticalization of

không, which became a standard negator by the late 19th century (

Trinh et al., 2024). Below are examples in which 不

bù, 無

wú, and 非

fēi are all translated as

không.

| (28) | 不 bù => không |

| a. | Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.21) |

| | 君子 | 矜 | 而 | 不 | 爭、 |

| | Quân tử | căng | nhi | bất | tranh. |

| | gentleman | proud | but | NEG | contentious |

| | 群 | 而 | 不 | 黨、 | |

| | Quần | nhi | bất | đảng”. | |

| | join | but | NEG | cliquish | |

‘The gentleman is proud but not contentious. He joins with others but is not cliquish’.

| b. | Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | Người quân tử | tự chủ bản thân, | giữ | quan điểm | nhưng |

| | CLF gentleman | control self | hold | opinion | but |

| | không | tranh giành, | cãi cọ. | | |

| | not | fight | argue | | |

| | Hợp quần | với | mọi người | nhưng | không | bè | phái |

| | join | with | people | but | not | ally | |

| | ‘The gentleman is proud but not contentious. He joins with others but is not cliquish’. |

| (29) | 無 wú => không or không có ‘not have’: |

| | a. Literary Sinitic (Chapter 17.23) |

| | 君子 | 有 | 勇 | 而 | 無 | 義 | 爲 | 亂 |

| | quân tử | hữu | dũng | nhi | vô | nghĩa | vi | loạn |

| | gentleman | have | courage | but | NEG | rightness | do | rebellious |

‘A gentleman who possesses courage but lacks rightness will become rebellious’.

| | b. Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | Quân tử | có | dũng | mà | không | có | nghĩa |

| | Gentleman | has | courage | but | NEG | have | rightness |

| | thì | làm | loạn | | | | |

| | TOP | make | rebel | | | | |

‘A gentleman who possesses courage but lacks rightness will become rebellious’.

| (30) | 非 fēi => không phải ‘not right’: |

| | a. | Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.28) |

| | 人 | 能 | 弘 | 道、 | 非 | 道 | 弘 | 人、 |

| | Nhân | năng | hoằng | đạo, | phi | đạo | hoằng | nhân |

| | Person | can | enlarge | Way, | NEG | Way | enlarge | person |

‘A person can enlarge the Way; it is not the case that the Way can enlarge a person’.

| | b. | Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | Con | người | có thể | hoằng dương | đạo lý, | chứ | không |

| | CLF | person | CAN | enlarge | | Way | but | NOT |

| | phải | đạo lý | hoằng dương | cho | con | người | |

| | right | Way | enlarge | | for | CLF | person | |

‘A person can enlarge the Way; it is not the case that the Way can enlarge a person’.

The 21st-century translation of the Analects exhibits a similar pattern to that of the 17th century, where Vietnamese mostly employed syntactic strategies rather than relying on lexical prefixation for negation. The key distinction, however, lies in the choice of the standard negator: while the 17th-century translation predominantly used chẳng to maintain the semantic distinctions of the Literary Sinitic negators, the 21st-century text continues this syntactic approach with không as the main negator. For example, in both periods, existential negation is expressed through the combination of a negator and an existential verb. In the 17th-century translation, this was typically rendered as chẳng có (‘not have’), as seen in example (21b), whereas in the 21st-century version, the same structure is realized as không có, as seen in example (29b). Similarly, for (verbless) nominal negation, the earlier translation used chẳng phải (‘not right’), as in (22b), which in the 21st-century translation becomes không phải, as in (30b). This suggests that, despite increased lexical borrowing from Chinese, Vietnamese uses the core grammatical strategies with compound structures like không có and không phải, allowing for precise differentiation between types of negation.

The increased appearance of Sino-Vietnamese prefixes, such as

bất and

vô, is also notable in this period.

Bất appears in five instances, and

vô in five instances as well, marking their integration into the Vietnamese lexical negation system. Just as in the 19th-century translation,

bất continues to appear, showcasing its role as a formal and fixed negator. However, while two of these instances were already present in the 19th-century translation, the 21st-century version introduces three more cases of

bất. Two of these three retain the original lexical form of Literary Sinitic, such as

bất thiện and

bất đồng, while the third offers a more innovative translation: the Literary Sinitic

bất hiền is rendered as

bất tiếu in Vietnamese. For instance, in Chapter 16.11 of the Literary Sinitic text, 不善

bù shàn is translated as

bất thiện:

| (31) | 不 bù => bất |

| | a. Literary Sinitic (Chapter 16.11) |

| | 見 | 不 | 善 | 如 | 探 | 湯 | |

| | kiến | bất | thiện | như | thám | thang | |

| | see | NEG | good | as | explore | scalding | water |

‘sees what is not good and acts as though he had put his hand in scalding water’.

| | b. Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | thấy | điều | bất | thiện | chạy | như | tránh | nước | sôi |

| | see | thing | NEG | good | run | as | avoid | water | boiling |

‘sees what is not good and acts as though he had put his hand in scalding water’.

Similarly, in Chapter 15.39, 不

bù is translated as

bất đồng:

| (32) | 不 bù => bất |

| | a. Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.39) |

| | 道 | 不 | 同 |

| | Đạo | bất | đồng |

| | way | NEG | same |

‘your Way is not the same’.

| | b. Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | Đạo lý | đã | bất | đồng |

| | way | PST | NEG | same |

‘your Way is not the same’

However, the translation becomes more innovative in Chapter 19.22. Instead of directly translating 不賢

bù xián ‘unworthy’ as

bất hiền, the 21st-century translation uses

bất tiếu (not worthy):

| (33) | 不 bù => bất |

| | a. Literary Sinitic (Chapter 19.22) |

| | 賢 | 者 | 識 | 其 | 大 | 者、 | |

| | Hiền | giả | chí | kì | đại | giả, | |

| | worthy | man | remember | PRT | essential | thing | |

| | 不 | 賢 | 者 | 識 | 其 | 小 | 者 |

| | bất | hiền | giả, | chí | kì | tiểu | giả, |

| | NEG | worthy | man | remember | PRT | minor | thing |

‘worthy men remember the essentials and those of little worth remember the minor points’.

| | b. Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | Bậc | hiền | giả | nhớ | được | cái | lớn, | kẻ | bất |

| | CLF | worthy | man | remember | CAN | CLF | big | man | NEG |

| | tiếu | nhớ | được | cái | nhỏ. | | | | |

| | worthy | remember | CAN | CLF | small | | | | |

‘worthy men remember the essentials and those of little worth remember the minor points’.

This innovation highlights the growing flexibility of bất in the modern Vietnamese lexicon, reflecting both the preservation of classical forms and the creative use of new ones to adapt to contemporary linguistic norms.

In addition to the prefix bất, vô makes its debut in the 21st-century translation, appearing in five instances that underscore its role in formalizing lexical negation. Notably, vô did not appear in the 17th- and 19th-century translations, marking its emergence solely in the 21st-century version. Unlike bất, which shows some innovative usages in Vietnamese, vô remains closely aligned with its original Literary Sinitic form, without deviations from the classical meanings.

In the following examples,

vô consistently retains its original sense of existential negation without creative reinterpretation or novel usage:

| (34) | 無 wú => vô |

| | a. Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.4) |

| | 無 | 爲 | 而 | 治 | 者 | 其 | 舜 | 也 | 與 |

| | Vô | vi | nhi | trị | giả | kỳ | Thuấn | dã | dư? |

| | NEG | action | but | rule | person | that | Shun | PRT | PRT |

‘Of those who ruled through inaction, surely Shun was one?’

| | b. Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | Người | thực hiện | nền | chính trị | vô vi | mà |

| | person | carry out | CLF | politics | inaction | but |

| | đất nước | thịnh trị | có lẽ | là | Thuấn | chăng |

| | country | peaceful | perhaps | is | Shun | PRT |

‘Of those who ruled through inaction but the country was peaceful, was Shun the one?’

In this instance,

vô vi is directly retained in the Vietnamese translation, preserving the original term from Literary Sinitic.

| (35) | 無 wú => vô |

| | a. Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.6) |

| | 邦 | 無 | 道 | 如 | 矢 |

| | Bang | vô | đạo | như | thỉ. |

| | state | NEG | way | as | arrow |

‘The state was without the Way, he was straight as an arrow’.

| | b. Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | Nước | vô | đạo | ông | cũng | thẳng | như | tên |

| | state | lack | way | PRN | still | straight | as | arrow |

‘The state was without the Way, he was straight as an arrow’.

Again, the phrase

vô đạo is preserved directly from the classical text.

| (36) | 無 wú => vô |

| | a. Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.3) |

| | 終 | 夜 | 不 | 寢 | 以 | 思 |

| | chung | dạ | bất | tẩm | dĩ | tư |

| | all | night | NEG | sleep | in order to | think |

| | 無 | 益 | | | | |

| | vô | ích | | | | |

| | no | use | | | | |

‘and all night without sleeping in order to think. It was no use’.

| | b. Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | Trọn | đêm | không | ngủ | để | nghĩ |

| | all | night | NEG | sleep | in order to | think |

| | nhưng | đều | vô ích | | | |

| | but | all | no use | | | |

‘and all night without sleeping in order to think. It was no use’

In this case,

vô ích maintains its classical meaning of ‘no use’.

| (37) | 無 wú => vô |

| | a. Literary Sinitic (Chapter 16.2) |

| | 天下 | 無 | 道 |

| | Thiên hạ | vô | đạo |

| | world | NEG | way |

‘When the Way no longer prevails in the world’.

| | b. Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | Thiên hạ | vô đạo |

| | world | lack way |

‘When the Way no longer prevails in the world’.

Here,

vô đạo once again aligns perfectly with its Literary Sinitic form.

| (38) | 無 wú => vô |

| | a. Literary Sinitic (Chapter 17.24) |

| | 惡 | 勇 | 而 | 無 | 禮 | 者 |

| | ố | dũng | nhi | vô | lễ | giả |

| | hate | courage | but | no | ritual | person |

‘He hates courage that ignores ritual decorum’.

| | b. Vietnamese translation (21st century) |

| | Ghét | kẻ | có | dũng | mà | vô lễ |

| | hate | person | have | courage | but | no ritual |

‘He hates courage that forgets ritual decorum’.

In this final example, vô lễ is faithfully translated as ‘no ritual’ in Vietnamese, closely following the classical meaning. The consistent appearance of vô in these examples demonstrates its seamless integration into the Vietnamese lexicon, with no notable departures from its original Literary Sinitic usage. Unlike bất, which sometimes exhibits innovative translation choices, vô adheres closely to its classical roots, highlighting its stability as a negation prefix in modern Vietnamese.

Unlike

bất and

vô,

phi does not appear in any of the three Vietnamese translations analyzed in this study. In the 21th-century translation, 非

fēi is consistently translated as

không, with

không phải, a common construction in modern Vietnamese that negates the truth of a statement or identity being the most commonly used form. This indicates a clear preference in Vietnamese for syntactic negation over lexical negation when considering (verbless) nominal negation constructions. Rather than employing a Sino-Vietnamese prefix equivalent to 非

fēi, such as

phi, Vietnamese translators favor the use of

không phải, a syntactic structure that aligns with the native patterns of negation, particularly in (verbless) nominal negative contexts. This aligns with a trend in Vietnamese to adapt and integrate negation strategies through syntactic combinations rather than adopting all lexical prefixes from Literary Sinitic.

| (39) | 非 fēi => không phải ‘not right’: |

| | a. Literary Sinitic (Chapter 15.1) |

| | 對 | 曰 | 然、 | 非 | 與、 |

| | Đối | viết: | “Nhiên. | Phi | dư?”5 |

| | reply | say | yes | NEG | Q |

‘Zigong replied, Yes, isn’t that so?’

| | b. Vietnamese translation (21th century) |

| | Đáp | rằng: | “Vâng, | chẳng lẽ | không | phải | ư?” |

| | reply | COMP | Yes | perhaps | NEG | right | Q |

‘Zigong replied, Yes, isn’t that so?’

The 21st-century translation of the

Analects marks a significant shift in the Vietnamese negation system, with

không firmly establishing itself as the dominant negator. Additionally, there is a notable increase in the use of

bất and

vô reflecting broader ‘linguistic modernization’ trends in Vietnam. This shift aligns with the larger cultural and linguistic modernization of East Asia, heavily influenced by Japan’s transmission of neologisms made of Chinese morphemes through reformist writings during the 20th century (

Sinh, 1993).

In this context, the integration of bất and vô into formal expressions, alongside the creative flexibility seen in the translation of bất tiếu ‘not worthy’, highlights the evolving role of Sino-Vietnamese prefixes in modern Vietnamese.

This 21st-century shift contrasts with earlier periods, such as the 17th-century translation, where chẳng overwhelmingly dominated, and the 19th century, where không and chẳng coexisted more equally. The gradual rise of không as the standard negator underscores the ongoing influence of Sino-Vietnamese elements in the language. The increased presence of bất and vô in the 21st century demonstrates the culmination of these linguistic trends, showing how Vietnamese has balanced the integration of Chinese lexical features with its own syntactic structures.

In summary, the 21st-century translation exemplifies the historical evolution of Vietnamese negation, with

không taking precedence while

bất and

vô gain prominence in specific contexts. This evolution is part of a broader cultural shift in East Asia, driven by modernization and the transmission of modernized Chinese linguistic features (

Sinh, 1993;

Alves, 2017).

5.4. Evidence from Earlier Texts

As highlighted earlier, the 17th-century Vietnamese translations of the Analects relied almost exclusively on native Vietnamese negators like chẳng, with no evidence of bất, vô, or phi. This pattern is consistent across earlier bilingual texts, suggesting a strong reliance on native Vietnamese negators in formal translations. For instance, in the Tân biên Truyền kỳ mạn lục tăng bổ giải âm tập chú 新編傳奇漫錄増補解音集註 (Interpretation of Legendary Tales: Newly Edited Collection with Supplementary Explanations and Pronunciation Annotations), (late 16th to 17th century), the translation of 不 bù, 無 wú, and 非 fēi similarly utilized native negators such as chẳng, chăng, and chớ.

As shown in

Table 9, the 16th- to 17th-century Vietnamese translations predominantly employed native sentential negators without integrating Sino-Vietnamese lexical prefixes. This reliance on native structures, especially for negation, persisted in earlier texts, indicating a gradual and selective integration of Sino-Vietnamese elements into the language. The transition to using prefixes such as

bất and

vô would not occur until the 19th and 20th centuries, suggesting that Vietnamese language and translation practices initially remained insulated from external lexical influences in the domain of negation.

By the 20th century, the rise of the sentential negator

không and the emergence of the negative prefixes

bất and

vô reflect broader shifts in the intellectual and linguistic landscape of Vietnam. These shifts align with the country’s ‘modernization’ efforts, which were significantly influenced by Chinese and Japanese intellectual movements, as well as by European colonialism. As noted by

Sinh (

1993), the reforms in Japan during the Meiji period played a crucial role in disseminating modernized Chinese-character-based vocabulary across East Asia, facilitating the eventual integration of Sino-Vietnamese elements, including

bất and

vô, into the Vietnamese lexicon. The literacy reforms and educational movements of the 20th century, particularly the promotion of the

Quốc ngữ script, further accelerated the standardization of the Vietnamese language. This standardization allowed for greater integration of Sino-Vietnamese prefixes into formal, academic, and philosophical texts. These reforms not only improved access to education but also reinforced the use of prefixes like

bất and

vô in domains where precision and formality were required.

By the 21st century,

bất and

vô had become firmly established in formal Vietnamese, particularly in academic and philosophical discourse. This is evident in modern translations of the

Analects, where these prefixes appear alongside

không, which had by then become the dominant negator for sentential negation. The growing prominence of

bất and

vô underscores the increasing formalization and modernization of Vietnamese in intellectual contexts, influenced by East Asian linguistic reforms in the early 20th century (

Hashimoto, 1978;

Alves, 2017;

Takahashi, 2022). The integration of Sino-Vietnamese prefixes into the modern lexicon reflects both Vietnam’s efforts to ‘modernize’ its language and educational system and the external influences from Chinese and Japanese reformists. Despite the increasing presence of

bất and

vô, however,

không remains the dominant negator, highlighting a balance between retaining native linguistic structures and incorporating new Sino-Vietnamese elements, and a division of labor between syntactic negation and lexical negation. This gradual yet dynamic evolution demonstrates the adaptability of the Vietnamese language in response to both internal and external changes.