2.1. Background on NC as Syntactic Agreement and the Typology of NC Languages

In this paper, I discuss NC within

Zeijlstra’s (

2004;

2008) analysis of NC as a syntactic Agree relation (

Chomsky, 1995,

2001) between a single interpretable negative feature [iNeg] and one or more uninterpretable negative features [uNeg], using Multiple Agree (

Hiraiwa, 2001). Negative feature checking is assumed to be upwards and phase-bound: probes bearing [uNeg] search for a c-commanding phasemate goal bearing [iNeg].

1I illustrate how this mechanism works for the two main types of NC languages that Zeijlstra identifies (following

Giannakidou, 1997): non-strict and strict. On the one hand, there are non-strict NC languages, like Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese, in which, descriptively, post-verbal negative indefinites (NIs) engage in NC with sentential negation (2-a), but preverbal ones do not (3-b).

| (2) | a. | María *(no) llamó a nadie. | b. | Nadie (#no) llamó. |

| | María neg called to nobody | | nobody (#neg) called |

| | María didn’t call anyone. | | Nobody called. |

For these languages,

Zeijlstra (

2004) proposed that there are two semantically negative operators able to license features on NIs: the sentential negation marker and a covert operator. The sentential negation is in the NegP, merged right above the vP. It can license negative items in positions it c-commands, namely post-verbal negative indefinites, as in (3-a). For preverbal NIs, namely subjects that have moved to spec-TP, the sentential negation is not in a c-commanding configuration, and therefore cannot be the licensor. In these cases, a higher covert negative operator is called for, as shown in (3-b).

| (3) | a. | [TP María [NegP no[iNeg] [vP llamó a nadie[uNeg] ]]] |

| b. | [Op¬[iNeg] [TP nadie[uNeg] [vP llamó ]]] |

We obtain as a result the non-strict pattern, where preverbal NIs, licensed by the covert operator, appear without a sentential negation marker, while postverbal NIs are licensed by and thus must appear with the overt sentential negation.

On the other hand, there are strict NC languages, where any NI must appear with sentential negation, whether it appears after or before the verb, as shown for Russian below.

| (4) | a. | Masha *(ne) zvonila nikomu. | b. | Nikto *(ne) zvonil. |

| | Masha neg called nobody | | nobody neg called |

| | Masha didn’t call anybody. | | Nobody called. |

Zeijlstra’s (

2004) proposal for these languages is that the sentential negation marker has uninterpretable negative features just like NIs, and a high covert negative operator, merged above the subject position, licenses both the sentential negation marker and the NIs.

| (5) | a. | [Op¬[iNeg] [TP Masha [NegP ne[uNeg] [vP zvonila nikomu[uNeg] ]]]] |

| b. | [Op¬[iNeg] [TP nikto[uNeg] [NegP ne[uNeg] [vP zvonil ] ] ] ] |

The requirement for the sentential negation marker to appear with NIs is not discussed by Zeijlstra himself, but one could argue that it is due to a requirement on the licensing of a covert negative operator: it can only appear if matching uninterpretable features are present on the clausal spine (a stipulation adopted in

Jeretič, 2022)—since sentential negation is on the clausal spine, but NIs are not, sentential negation is obligatory to invoke the covert negative operator.

2.2. The Typology of NC Extended to SOV Languages

In Zeijlstra’s system, the negativity status of negation is a factor that determines whether a NC language has a strict or non-strict pattern: a negative negation marker results in a non-strict pattern, while a non-negative one results in a strict pattern. However, this explanation does not straightforwardly extend to SOV languages.

Unlike in SVO languages, being preverbal in an SOV language does not imply being hierarchically superior to the verb, which determines whether an element can be licensed by a vP-level negation marker. We therefore cannot reach the same conclusions about the negativity of negation in a language with SOV word order based on observing a strict or non-strict NC pattern, whose definitions rely on the notion of ‘preverbal’ elements. Indeed, objects in SOV languages are preverbal but are assumed to merge below the verb and, in simple cases, not move above it

2 (just like they do in SVO languages). Therefore, object NCIs can be licensed by a negation that merges above the verb, despite being preverbal. What about subjects? Just like objects, the hierarchical relation between a subject and a head negation is not reflected by linear order, because the subject, as a specifier, is in an initial position, and the head negation takes a final position. The question of the movement of subjects from their standardly assumed base-merge position in spec-vP to a vP-external position above the verb (typically spec-TP) in SOV languages is subject to debate. In fact, the answer might vary across languages and configurations. Diagnostics other than linear order are needed to determine the position of the subject; we discuss this question for Turkish in the

Section 2.4. Now, we lay out the expected typology of the NC patterns of SOV languages whose negation marker merges right above the vP, depending on (a) whether (NCI) subjects move out of the vP, and (b) whether negation is negative.

If subjects are in spec-TP, they are located above the position of negation. Among SOV languages with subjects in spec-TP, we might expect to observe the following typological divide determined by the negativity status of negation: if negation has interpretable negative features, subject NCIs do not co-occur with it, as shown in (6-a) (akin to non-strict NC SVO languages); if it does not, then subject NCIs must co-occur with it, as shown in (6-b) (akin to strict NC SVO languages). I assume objects stay in the vP and thus can be licensed by the negative operator, whether it is low or high.

| (6) | Expected types of SOV languages with subject NCIs above NegP: |

| a. | Negative negation. |

| | (i) | Subject NCI: [TP nobody[uNeg] [NegP [vP arrive ] Neg¬[iNeg] ]] |

| | (ii) | Object NCI: [TP Mary [NegP [vP nobody[uNeg] see ] Neg¬[iNeg] ]] |

| b. | Non-negative negation. |

| | (i) | Subject NCI: [[TP nobody[uNeg] [NegP [vP arrive ] Neg[uNeg] ]] Op¬[iNeg]] |

| | (ii) | Object NCI: [[TP Mary [NegP [vP nobody[uNeg] see ] Neg[uNeg] ]] Op¬[iNeg]] |

As far as the literature on NC goes, no language has been claimed to have the surface pattern in (6-a), where high NCIs in SOV languages do not require sentential negation to be licensed. This may be considered an accident or have a principled reason (e.g., a result of a learning bias).

In contrast, if subject NCIs stay in spec-vP, then they can always be licensed by a negation marker, whether that marker is negative or not, and we should expect all NC languages with such low subjects to have a strict pattern, as shown below in the structures in (7-a(i)) and (7-b(i)). Object NCIs are also in the vP and again licensed by sentential negation regardless of its position.

| (7) | Expected types of SOV languages with subjects below NegP: |

| a. | Negative negation. |

| | (i) | Subject NCI: [NegP [vP nobody[uNeg] arrive ] Neg¬[iNeg] ] |

| | (ii) | Object NCI: [NegP [vP Mary nobody[uNeg] see ] Neg¬[iNeg] ] |

| b. | Non-negative negation. |

| | (i) | Subject NCI: [[NegP [vP nobody[uNeg] arrive ] Neg[uNeg] ] Op¬[iNeg]] |

| | (ii) | Object NCI: [[NegP [vP Mary nobody[uNeg] see ] Neg[uNeg] ] Op¬[iNeg]] |

Because these two types of languages are not different on the surface, at least in these simple cases, the status of negation in strict NC SOV languages with subjects in spec-vP is underdetermined.

Therefore, if we consider the variation in the position of subjects and the negativity of negation, we have three possible grammars for SOV languages with a surface strict NC pattern: (6-b) (high NCI subjects, non-negative negation), (7-a) (low NCI subjects, negative negation) and (7-b) (low NCI subjects, non-negative negation). Only one of them, (7-a), has a negative negation; hence, SOV languages indeed break the correlation between the negativity of negation and the strictness of the NC pattern argued by Zeijlstra.

Note there is an additional relevant point of variation within grammars of the (7-b) type: the position of the covert operator. It may be found merged below the TP (and right above the Neg head, e.g., spec-NegP) or above the TP. This means that if in a given language, the locus of interpretable negation is found to always be below the TP, its grammar is still compatible with (7-a) and (7-b). This point becomes relevant when we look at Turkish.

The multiplicity of logical possibilities for a grammar of an SOV language with a strict NC pattern begs the questions: Are all attested, or just a subset thereof? And how does the learner decide on one of these grammars? While the basic structures presented above converge on the surface, there may be other structures that do not, thus allowing the learner to determine the grammar of their input. But it also may be that there are no such structures, or insufficient evidence in the input that differentiates between the options. In such cases, the learner might decide on a grammar randomly, which therefore could be different from that of their input, or follow some learning heuristic that will favor one grammar over the other. For instance, we could imagine a preference for the sentential negation marker to be negative, as it results in a simpler and more transparent grammar than if it were not.

In this paper, we look for evidence to determine which of these grammars corresponds to the one(s) spoken by Turkish speakers. In order to do so, we first discuss the position of NCI subjects, together with that of semantic negation. After showing the basic facts that make Turkish a strict NC language in

Section 2.3, we argue in

Section 2.4 that Turkish is likely to be a language in which NCI subjects remain in spec-vP and are furthermore licensed by a negation found below the TP.

This finding narrows down the possible grammars of Turkish to the ones listed in (7). However, it does not decide on the negativity status of negation: either the negation marker itself carries semantic negation, as in (7-a), or we have a covert negative operator merged right above the Neg head and below the TP, as in (7-b).

We therefore need further investigation to determine the status of the negativity of the negation markers in Turkish. We do so in

Section 3, which reveals a heterogeneous picture across Turkish speakers.

2.4. The Position of NCI Subjects and Semantic Negation in Turkish

Authors are not in full agreement on the position of subjects in Turkish, namely whether they are in spec-vP or spec-TP. Traditionally, it is assumed that subjects in Turkish move to spec-TP to satisfy the EPP and receive case (

Aygen, 2002;

Kelepir, 2001;

Kornfilt, 1984;

Kural, 1993, a.o.). In fact, this assumption has driven authors like

Kelepir (

2001) to propose the existence of a covert semantic negation above the position of the subject, so as to allow for licensing of subject NCIs (just as Zeijlstra proposed for strict NC SVO language, and the option laid out in (6-b)).

However, there is a body of work that challenges the idea that all subjects must move to spec-TP (

İşsever, 2008;

Kornfilt, 2020;

Öztürk, 2002,

2004), and instead, in some cases, subjects can stay in spec-vP (the EPP then being satisfied by movement of v to T, à la

Alexiadou & Anagnostopoulou, 1998), and only raise to spec-TP to achieve wide scope (e.g., specific interpretations for indefinites).

Indeed, quantifier subjects have ambiguous scope with respect to negation (some speakers disallow , for others it is simply marked; other quantifier expressions, e.g., numerals, proportion expressions, are more robustly ambiguous between the two scopes).

| (9) | a. | Her çocuk gel-me-di. |

| | all child come-neg-pst |

| | All children did not come. |

| b. | Üç çocuk gel-me-di. |

| | three child come-neg-pst |

| | Three children did not come. |

This ambiguity shows that quantifiers occur below negation in their base position, and are able to raise above it. The question remains: do they raise above it and then reconstruct at LF? Or do they have the option to stay below and raise only for interpretative purposes?

The low position of subjects has been proposed by

Öztürk (

2002,

2005), who posits that subjects in Turkish generally do not move to spec-TP, unless it is to achieve a higher semantic scope. Öztürk’s main argument has to do with the fact that scope relations with universal quantifiers correlate with agreement on the verb: in the absence of plural agreement on the verb, universal quantifiers like

bütün scope low with respect to negation, while when plural agreement is present, they take wide scope (some speakers allow wide scope of

bütün in (9-a) and narrow scope in (9-b); in both these cases, wide scope

bütün is stressed (Jaklin Kornfilt, p.c.)).

| (10) | a. | Bütün çocuklar o test-e gir-me-di. | |

| | all children that test-dat take-neg-pst | |

| | All children didn’t take that test. | (%all>not, not>all) |

| b. | Bütün çocuklar o test-e gir-me-di-ler. | |

| | all children that test-dat take-neg-pst-pl | |

| | All children didn’t take that test. | (all>not, %not>all) |

The wide scope of the universal quantifier shows that it has moved above the semantic position of negation. According to Öztürk, the plural agreement on the tensed verb is a morphological reflex of the movement of the subject to spec-TP.

4 Hence the unavailability of the narrow scope of the universal quantifier. If Öztürk’s analysis is right, it shows several things: first, that the subject need not move to spec-TP, second, if it does, it must scope above the semantic position of negation, which therefore must be merged between the vP and TP, and third, if it does move to spec-TP, it cannot reconstruct below negation, at least when it triggers plural agreement on the verb.

Since semantic negation is above the vP but not the TP, subject NCIs can only be licensed by it in their vP-internal position. They furthermore must stay there, because they are interpreted there (as expected from their nature as existential quantifiers, needing to scope below negation), and we assume they cannot, like subjects that trigger plural agreement on the verb, reconstruct.

We provide an additional argument for both Öztürk’s claim that plural agreement correlates with scope with respect to negation, as well as a low position for NCI subjects: NCI subjects are incompatible with plural agreement on the verb, as shown below.

| (11) | Hiçbir-imiz-in arkadaş-lar-ı gel-me-di-(*ler). |

| none-poss.1pl-gen friend-pl-acc come-neg-pst-(*pl) |

| None of our friends came. (lit. friends of none of us came) |

Note that it was crucial to construct the sentence with an embedded NCI, here in a possessive structure, because a bare NCI would not be expected to trigger plural agreement in the first place, due to its singular number marking with bir (‘one’). I further note that the possessive structure is not the culprit for the lack of plural marking, as we can see in the following example (note: the judgments are subtle for some speakers, but everyone agrees that (11) is worse than the sentences in (12)).

| (12) | a. | Öğrenci-nin arkadaş-lar-ı gel-me-di-(ler). |

| | student-gen friend-pl-acc come-neg-pst-(pl) |

| | The students’ friends didn’t come. |

| b. | Hep-imiz-in arkadaş-lar-ı gel-di-(ler). |

| | all-poss.1pl-gen friend-pl-acc come-pst-(pl) |

| | All of our friends came. |

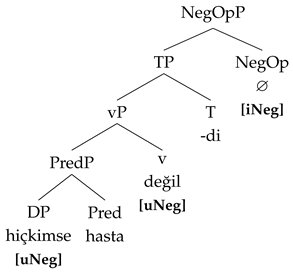

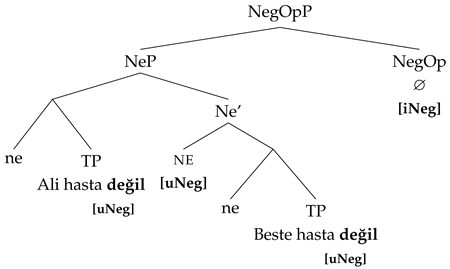

This result therefore supports an analysis of Turkish of one of the types in (7), in which subject NCIs must stay in spec-vP, to be licensed by a semantic negation located either at the negation marker -ma, which is found between the verb and tense, or right above it (but below the TP).

Note: the claim that NCI subjects must stay in the vP domain opens up questions about case-licensing. While in matrix clauses nominative case is null, nominalizations mark subjects with genitive marking, at least when they are specific. And it is natural to assume that genitive marking, usually correlated with specificity, is received in spec-TP (

Kornfilt, 2020, a.o.). However, an NCI subject can receive genitive case in a nominalization, as shown in (13).

| (13) | Hiçkimse-nin | köy-ü | bas-ma-dığ-ın-ı | duy-du-m. |

| nobody-gen | village-acc | raid-neg-nmz-3s-acc | hear-pst-1s |

| I heard that nobody raided the village. |

One possibility would be to allow case-marking at a distance, or to allow non-interpretable movement of the NCI for it to receive case, after its negative features have been checked in spec-vP. This could also cover cases in which genitive plural subjects receive non-specific interpretations (as discussed in

Kornfilt, 2020). I leave this open question to future work and assume that NCIs must remain in spec-vP.

We now move to determining the negativity status of negation with an independent diagnostic: we will create configurations in which the negation markers are in the scope of another negative operator, thus giving them the chance, if they are indeed non-negative, to be licensed not by the covert operator that typically licenses them, but by another negative operator. If they are negative, they should unambiguously yield double negation readings.