The Addition of a Target Structure to Task Repetition as an Accuracy Enhancement: The Necessity of Reducing Cognitive Load

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Task Repetition, Fluency Enhancement and FoF

2.2. Variability: An Obstacle to the Acquisition of Grammatical Knowledge?

2.2.1. Constant/Blocked vs. Variable Practice and Development of Grammar Declarative Knowledge

2.2.2. Development of Procedural Knowledge and Cognitive Load

2.2.3. The Development of Procedural Knowledge Within the Framework of a Task

2.3. Critique of an FoF When the TS Is Chosen Prior to the Task

2.4. The Motivations for the Current Study

- To what extent does the production of an idea related to what a partner has just said facilitate fluent use of a TS?

- To what extent does this type of FoF reinforce, or not, the accurate use of a TS?

- Does this type of FoF allow the learner to use the TS in a new task?

3. The Current Study

3.1. Participants

3.2. Design

3.3. Treatment

3.4. Target Structure

3.5. Scoring

3.5.1. Training Phase

3.5.2. New Task

4. Results

4.1. Fluent and Accurate Use of Target Structure

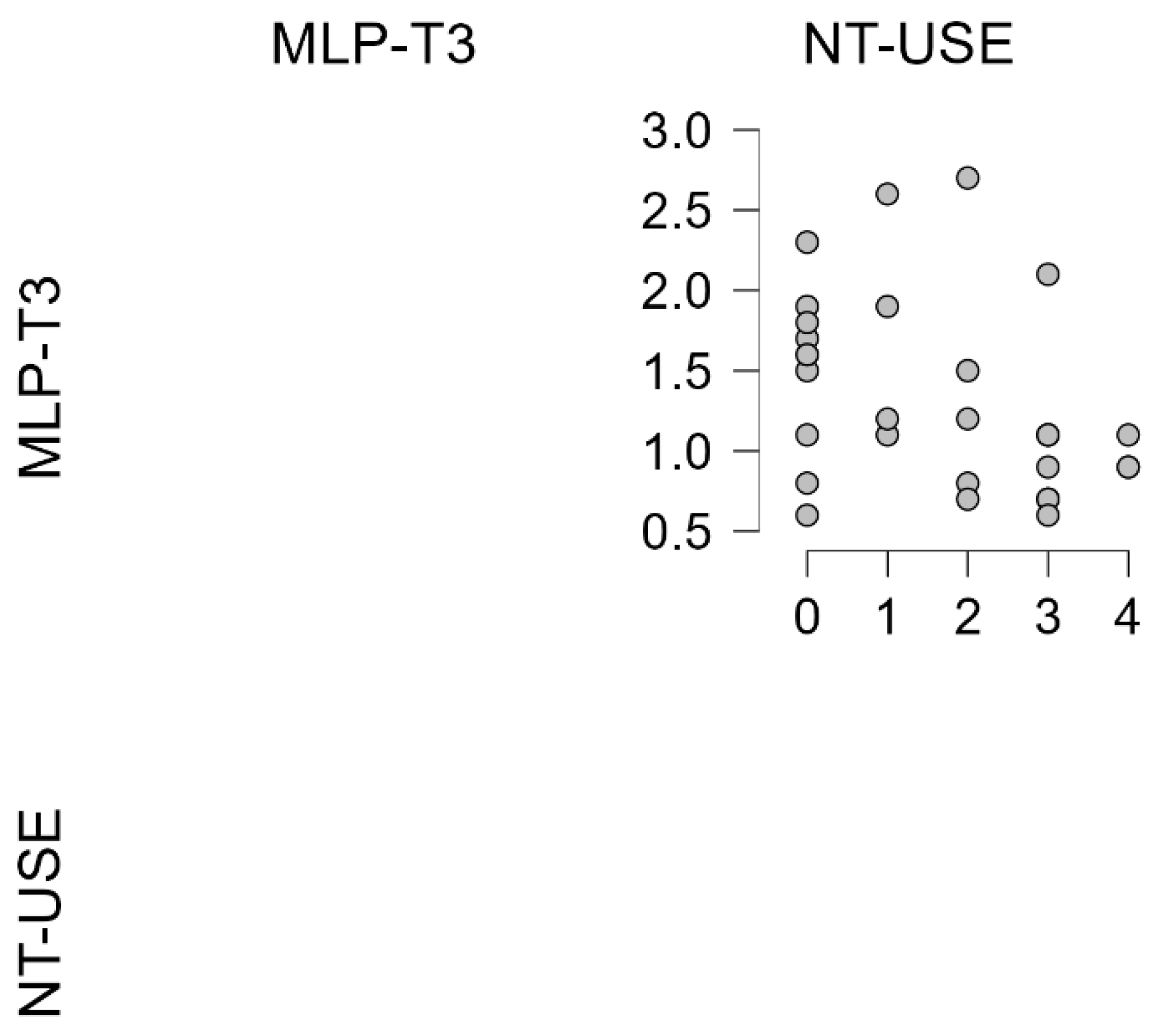

4.2. Avoidance Phenomenon and Correlation with Average Length of Pauses

5. Discussion

5.1. Fluency Changes in the Target Structure

5.2. Accuracy Changes in the Target Structure

5.3. Contextualized Grammar Learning and Avoidance Phenomenon

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bird, S. (2010). Effects of distributed practice on the acquisition of second language English syntax. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31, 635–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, F. (2014). A reappraisal of the 4/3/2 activity. RELC Journal, 45(3), 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunmair, M., & Richter, T. (2019). Similarity matters: A meta-analysis of interleaved learning and its moderators. Psychological Bulletin, 145, 1029–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, G., Ahmadian, M. J., & Hunter, A. M. (2019). Spacing effects on repeated L2 task performance. System, 81, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bygate, M. (2018). Learning language through task repetition. John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M., & Li, W. (2022). The influence of form-focused instruction on the L2 Chinese oral production of Korean native speakers. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 790424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, N., & Bosker, H. R. (2013, August 21–23). Choosing a threshold for silent pauses to measure second language fluency. 6th Workshop on Disfluency in Spontaneous Speech, Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, N., & Perfetti, C. A. (2011). Fluency training in the ESL classroom: An experimental study of fluency development and proceduralization. Language Learning, 61, 533–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeKeyser, R. M. (2001). Automaticity and automatization. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 125–151). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeKeyser, R. M. (2020). Skill acquisition theory. In B. VanPatten, G. D. Keating, & S. Wulff (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (3rd ed., pp. 83–104). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R. (2018). Reflections on task-based language teaching. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R. (2019). Towards a modular language curriculum for using tasks. Language Teaching Research, 23(4), 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housen, A., & Simoens, H. (2016). Introduction: Cognitive perspectives on difficulty and complexity in L2 acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 38(2), 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, C. L., Cho, S.-J., & Watson, D. G. (2019). Self-priming in production: Evidence for a hybrid model of syntactic priming. Cognitive Science, 43, e12749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, J. (2006). Speech production and second language acquisition. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, C., Kormos, J., & Minn, D. (2017). Task repetition and second language speech processing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 39(1), 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M. H. (2015). Second language acquisition and task-based language teaching. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Long, M. H. (2016). In defense of tasks and TBLT: Nonissues and real issues. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loschky, L., & Bley-Vroman, R. (1993). Grammar and task-based methodology. In G. Crookes, & S. Gass (Eds.), Tasks and language learning: Integrating theory and practice (pp. 123–167). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, K., Neumann, H., & Trofimovich, P. (2015). Eliciting production of L2 target structures through priming activities. Canadian Modern Language Review, 71, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, G. (2019). À quel moment enseigner la forme dans le cadre d’un enseignement basé sur la tâche? [Doctoral thesis, Université de Montréal]. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, G., & Ammar, A. (2023). Explicit instruction within a task: Before, during, or after? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(2), 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, T., & Suzuki, Y. (2019). Mixing grammar exercises facilitates long-term retention: Effects of blocking, interleaving, and increasing practice. The Modern Language Journal, 103, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nergis, A. (2021). Can explicit instruction of formulaic sequences enhance L2 oral fluency? Lingua, 255, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pica, T. (1983). Methods of morpheme quantification: Their effect on the interpretation of second language data. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 6(1), 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pienemann, M. (1989). Is language teachable? Psycholinguistic experiments and hypotheses. Applied Linguistics, 10, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plonsky, L., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). How big is “big?” Interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Language Learning, 64, 878–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J. (2015). Learning second language syntax under massed and distributed conditions. TESOL Quarterly, 49(4), 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M., & McDonough, K. (2019). Practice is important but how about its quality? Contextualized practice in the classroom. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 41, 999–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skehan, P. (2014). Limited attentional capacity, second language performance and task-based pedagogy. In P. Skehan (Ed.), Processing perspectives on task performance (pp. 211–262). Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Y. (2021). Optimizing fluency training for speaking skills transfer: Comparing the effects of blocked and interleaved task repetition. Language Learning, 71, 285–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y. (2023). Introduction: Practice and automatization in a second language. In Y. Suzuki (Ed.), Practice and automatization in second language research: Perspectives from skill acquisition theory and cognitive psychology (pp. 1–36). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Y., & DeKeyser, R. (2015). Effects of distributed practice on the proceduralization of morphology. Language Teaching Research, 21, 166–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y., Eguchi, M., & de Jong, N. (2022). Does the reuse of constructions promote fluency development in task repetition? A usage-based perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 56, 1290–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y., & Hanzawa, K. (2022). Massed task repetition is a double-edged sword for fluency development: An EFL classroom study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 44, 536–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, C., & Boers, F. (2016). Repeating a monologue under increasing time pressure: Effects on fluency, complexity, and accuracy. TESOL Quarterly, 50(2), 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M. N., & Saito, K. (2021). Effects of the 4/3/2 activity revisited: Extending Boers (2014) and Thai & Boers (2016). Language Teaching Research, 28(2), 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Guchte, M., Braaksma, M., Rijlaarsdam, G., & Bimmel, P. (2016). Focus on form through task repetition in TBLT. Language Teaching Research, 20(3), 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R., Kim, S.-A., & Shin, J.-A. (2022). Structural priming and inverse preference effects in L2 grammaticality judgment and production of English relative clauses. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 845691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

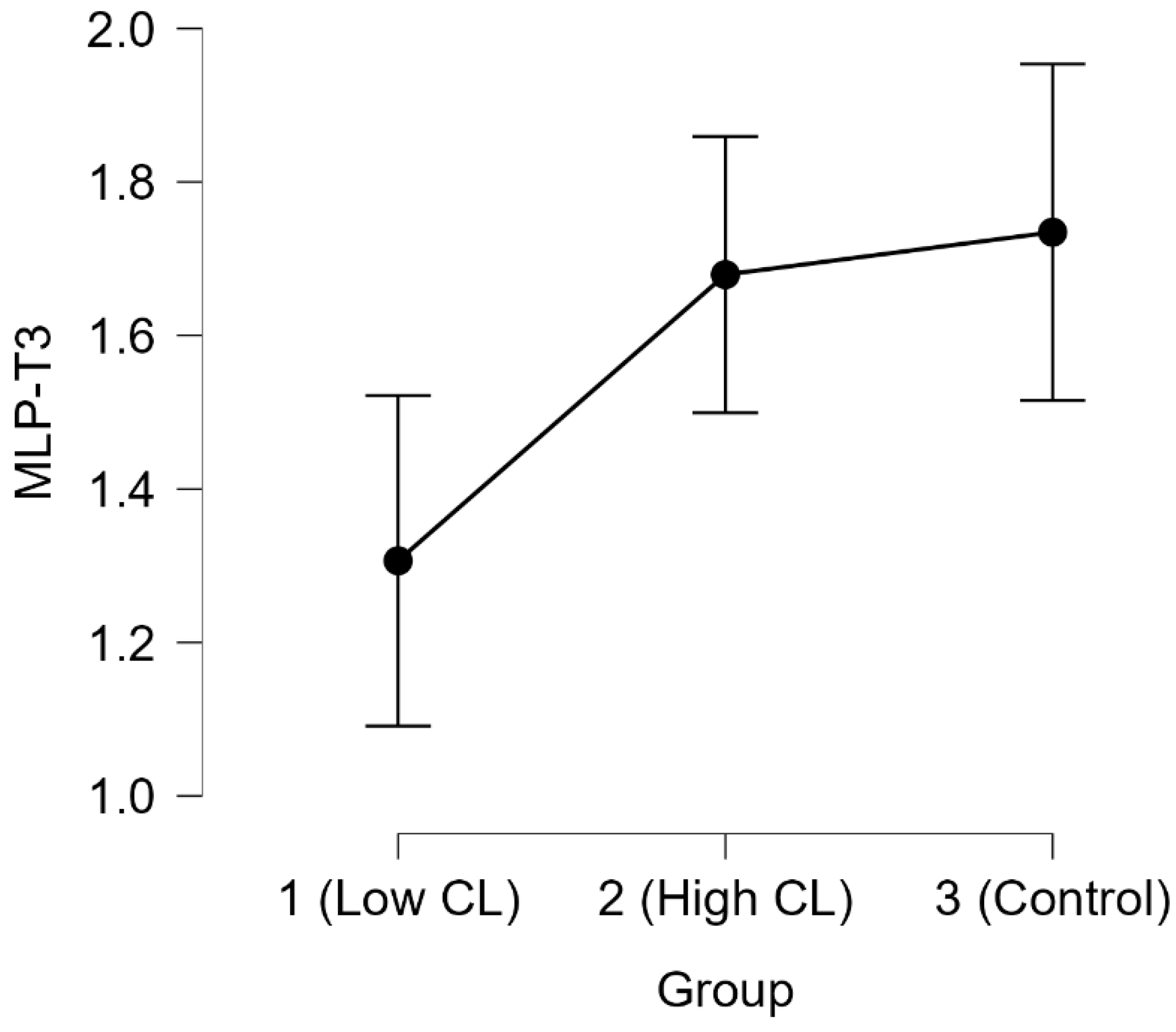

| Mean Difference | SE | t | Cohen’s d | pholm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | −0.373 | 0.139 | −2.686 | −0.694 | 0.017 |

| 3 | −0.428 | 0.143 | −2.996 | −0.797 | 0.011 | |

| 2 | 3 | −0.055 | 0.145 | −0.381 | −0.103 | 0.704 |

| Mean Difference | SE | t | Cohen’s d | pholm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0.096 | 0.046 | 2.094 | 0.541 | 0.079 |

| 3 | 0.147 | 0.047 | 3.111 | 0.827 | 0.008 | |

| 2 | 3 | 0.051 | 0.048 | 1.060 | 0.286 | 0.292 |

| Mean Difference | SE | t | Cohen’s d | pholm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0.091 | 0.045 | 2.042 | 0.528 | 0.089 |

| 3 | 0.164 | 0.046 | 3.569 | 0.949 | 0.002 | |

| 2 | 3 | 0.073 | 0.047 | 1.560 | 0.421 | 0.122 |

| Mean Difference | SE | t | Cohen’s d | pholm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0.813 | 0.325 | 2.506 | 0.647 | 0.028 |

| 3 | 1.056 | 0.334 | 3.161 | 0.841 | 0.007 | |

| 2 | 3 | 0.243 | 0.339 | 0.715 | 0.193 | 0.476 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buhot, N.; Xing, Q. The Addition of a Target Structure to Task Repetition as an Accuracy Enhancement: The Necessity of Reducing Cognitive Load. Languages 2025, 10, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10060128

Buhot N, Xing Q. The Addition of a Target Structure to Task Repetition as an Accuracy Enhancement: The Necessity of Reducing Cognitive Load. Languages. 2025; 10(6):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10060128

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuhot, Nicolas, and Qiang Xing. 2025. "The Addition of a Target Structure to Task Repetition as an Accuracy Enhancement: The Necessity of Reducing Cognitive Load" Languages 10, no. 6: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10060128

APA StyleBuhot, N., & Xing, Q. (2025). The Addition of a Target Structure to Task Repetition as an Accuracy Enhancement: The Necessity of Reducing Cognitive Load. Languages, 10(6), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10060128