World Englishes demonstrate the adaptability of English across diverse linguistic, cultural, and historical contexts, shaping distinct phonological and prosodic characteristics. In multilingual societies, language variation is not just structural but also a marker of identity, as speakers adjust their speech to different social contexts. Philippine English (PhE) has evolved within a multilingual society influenced by American English and over 170 local languages. As a nativized variety

1, PhE reflects an interplay between global linguistic norms and indigenous languages, resulting in distinctive phonological, grammatical, and rhythmic features. Scholars such as

Borlongan (

2023) and

Schneider (

2003,

2023) recognize PhE as an independent English variety with its own linguistic norms, reinforcing its status within the World Englishes paradigm.

1.1. Sociolectal Variation in PhE

PhE is shaped by both historical factors—including American colonial rule, which institutionalized English as a medium of instruction and governance—and the contemporary multilingual reality, where English coexists with over 170 local languages. These sociolinguistic conditions have given rise to sociolectal variation, a phenomenon in which distinct linguistic features emerge within different social groups shaped by unequal access to English across education, media, and institutional settings (

Tayao, 2004).

A sociolect refers to a linguistic variety spoken by a particular social group, distinguished by phonological, grammatical, or lexical differences that correlate with social variables such as class, education, occupation, and linguistic exposure. In the case of PhE, sociolectal variation is commonly described using three prototypical reference points—acrolect, mesolect, and basilect—rather than as rigid categories. These labels represent salient clusters of linguistic features, but speakers often occupy intermediate positions, reflecting a gradient continuum of variation rather than strictly bounded varieties (

Magpale, 2024;

Magpale & Hong, 2024). This study adopts

Tayao’s (

2004) framework, which conceptualizes PhE sociolectal stratification, but extends it by operationalizing sociolectal status through frequency of English use across social domains and self-rated English proficiency (see

Section 2.1). These measurable factors provide a quantitative basis for distinguishing sociolects, ensuring consistency in classification.

PhE acrolect is spoken by individuals with high English proficiency, typically those who have received formal education in English-medium institutions and have greater exposure to English in academic and professional settings. PhE acrolect speakers exhibit phonological features aligned with general American English, including a full consonantal and vowel inventory, and characteristics such as vowel reduction in unstressed syllables (

Lesho, 2017).

PhE mesolect represents a transitional sociolect, where speakers exhibit phonological features from both the PhE acrolect and PhE basilect due to bilingual interaction between English and Filipino. This variety is characterized by partial vowel reduction and epenthesis in consonant clusters, indicating phonotactic influences from both the English and Philippine languages (

Tayao, 2008).

PhE basilect is the most localized sociolect, strongly influenced by Philippine languages and typically spoken by individuals with limited formal education in English and less frequent exposure to English-speaking environments. Speakers of this variety exhibit phonological substitutions (e.g., /f/ → /p/, /v/ → /b/), reduced vowel inventories, and a more syllable-timed rhythm, reflecting influences from local Philippine languages (

Regala-Flores, 2014).

Beyond these segmental characteristics, each sociolect also exhibits distinct phonological processes that have implications for rhythmic variation. Vowel reduction, often observed in PhE acrolectal speech (

Lesho, 2017;

Magpale, 2024), involves the weakening or centralization of unstressed vowels, which contributes to increased variability in vocalic duration and lends a more stress-timed quality to speech. In contrast, epenthesis—the insertion of a vowel, typically /ɪ/, within consonant clusters—is more frequently found in PhE basilectal speech (

Magpale & Hong, 2024), leading to more evenly timed syllables, increasing vocalic regularity and reducing temporal variation. Additionally, consonant cluster simplification, where complex onsets or codas are reduced (e.g., /str/ → / ɪs.tr/), is more common among PhE mesolectal and basilectal speakers (

Tayao, 2004;

Regala-Flores, 2014), reflecting both articulatory ease and the influence of Philippine languages. These processes not only shape phonotactic structure but also modulate speech timing, offering valuable insight into the prosodic distinctions across PhE sociolects.

The directionality of these variables follows a clear pattern: individuals with greater English exposure, formal education, and access to English-dominant domains tend to align with PhE acrolect, whereas those with lower exposure, limited formal education, and stronger local language influence tend to align with PhE basilect. PhE mesolect occupies a middle ground, reflecting a hybrid linguistic profile that adapts to varying communicative contexts.

Recent research has expanded our understanding of these sociolectal differences by modeling linguistic variation using probabilistic approaches. For instance,

Magpale (

2024) and

Magpale and Hong (

2024) employed constraint-based grammars to capture the gradient nature of sociolectal variation, demonstrating that linguistic features shift dynamically across the PhE acrolect–mesolect–basilect continuum. While these studies offer valuable insights into segmental and suprasegmental variation, they have not explored rhythmic aspects such as speech rhythm in depth. This study aims to bridge this gap by analyzing rhythm as a sociolinguistic marker of sociolectal identity, contributing to the broader discussion on prosody, phonological variation, and linguistic diversity in World Englishes.

1.2. Rhythm in Linguistic Typology and Quantitative Analysis

Speech rhythmic typology traditionally categorizes languages into stress-timed, syllable-timed, or mora-timed based on the distribution of rhythmic units. Stress-timed languages, such as English and German, have intervals between stressed syllables occurring at roughly regular intervals, resulting in variable syllable lengths. In contrast, syllable-timed languages, like Spanish and French, exhibit syllables of nearly equal duration regardless of stress. Mora-timed languages, such as Japanese, maintain uniform timing for morae, a smaller unit within syllables (

Ladefoged & Johnson, 2011).

While these classifications have been widely used, early rhythm studies relied on perceptual observations, which often resulted in inconsistent language classifications (

Dauer, 1983;

Dasher & Bolinger, 1982). To address this limitation, researchers have developed quantitative rhythm metrics to systematically measure temporal patterns in speech and provide empirical validation for rhythm typologies.

One of the key developments in rhythm studies was the introduction of rhythm metrics by

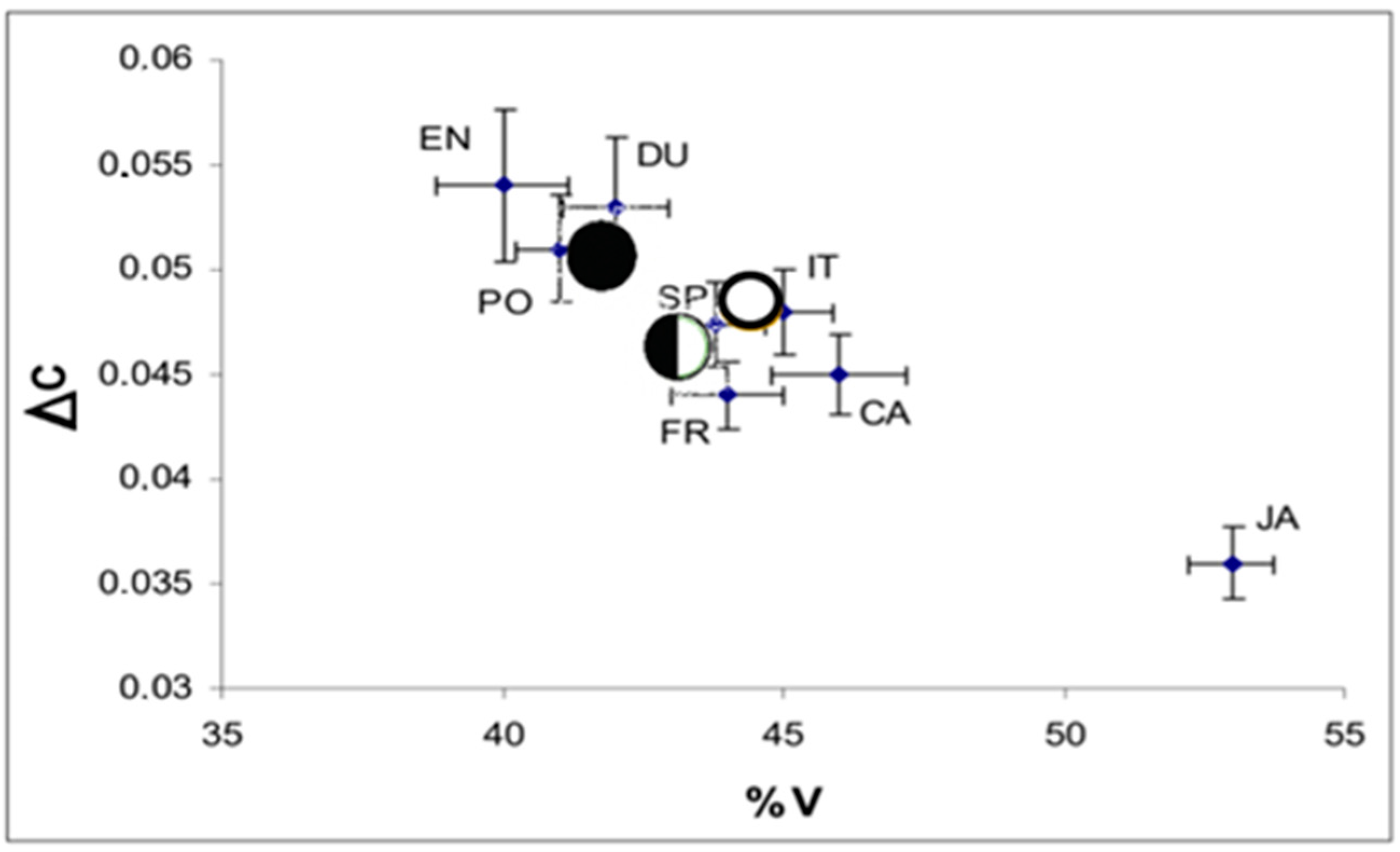

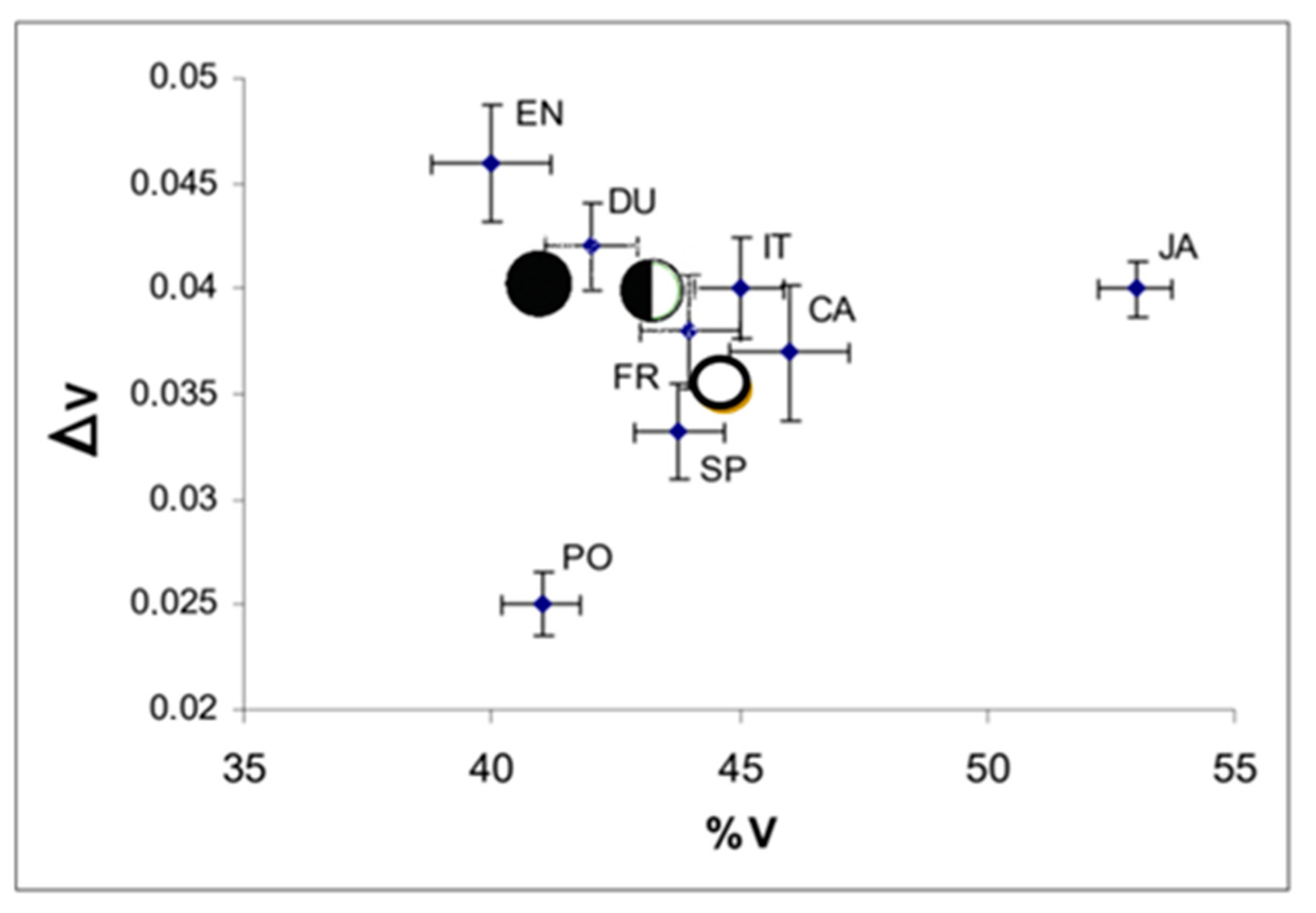

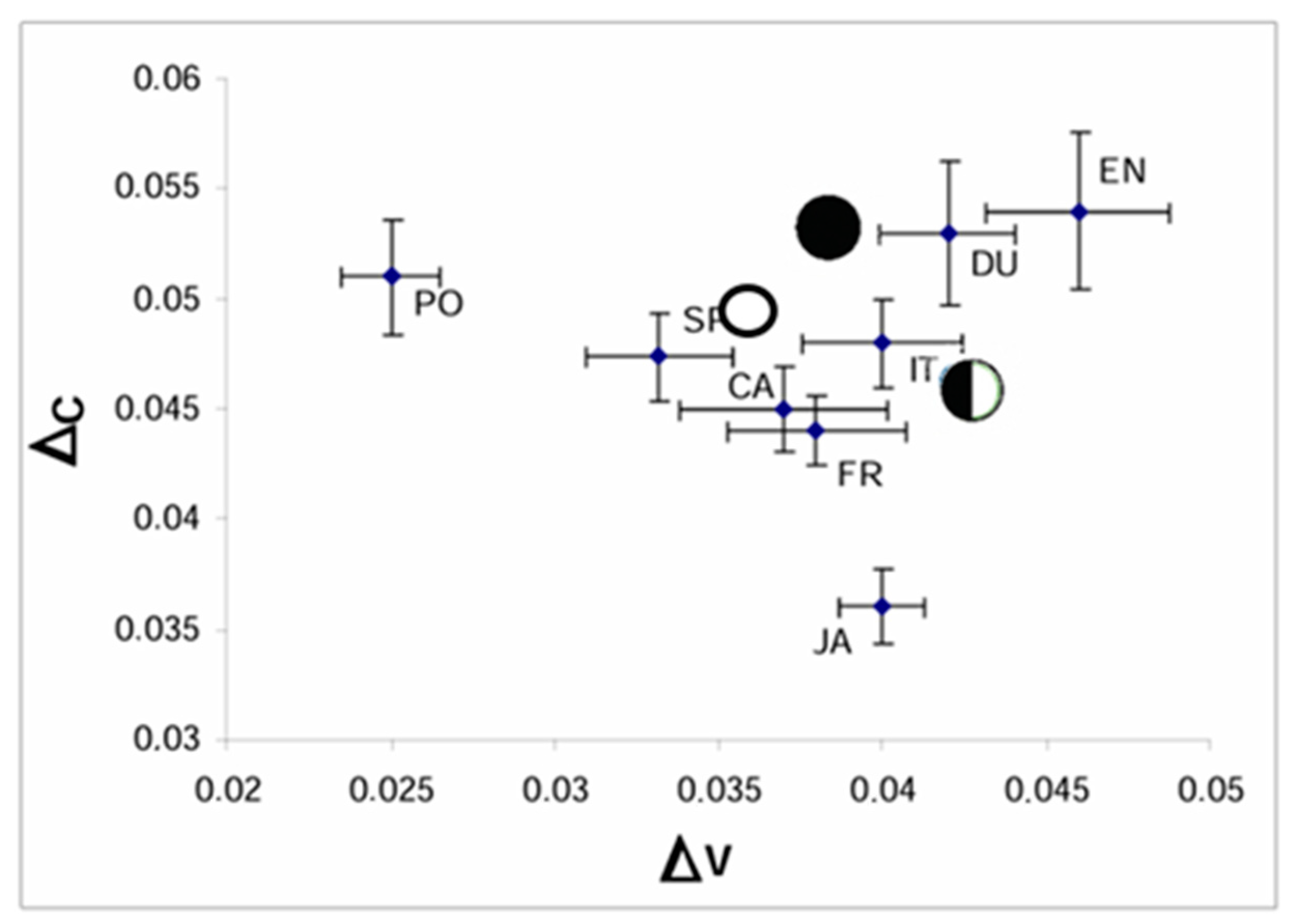

Ramus et al. (

1999), which provided a standardized method for analyzing rhythmic variability. Their metrics—%V (proportion of vocalic intervals), ΔV (standard deviation of vowel durations), and ΔC (standard deviation of consonant durations)—are widely used to measure variability in vocalic and consonantal intervals.

The %V metric, which represents the proportion of an utterance occupied by vowels, is particularly useful in distinguishing between stress-timed and syllable-timed languages. Stress-timed languages (e.g., English, Dutch) tend to have lower %V values due to extensive vowel reduction and complex syllable structures, often featuring consonant clusters. In contrast, syllable-timed languages (e.g., Spanish, French) exhibit higher %V values, as vowels are more consistently realized, and syllable durations remain relatively stable across speech. Mora-timed languages (e.g., Japanese) tend to display %V values distinct from both categories, reflecting their unique rhythmic organization.

In addition to %V, ΔV (the standard deviation of vowel durations) and ΔC (the standard deviation of consonant durations) quantify rhythmic variability by measuring durational differences within vocalic and consonantal intervals.

Ramus et al. (

1999) found that %V and ΔC were strongly correlated, indicating that they captured similar aspects of syllable structure and vocalic-consonantal balance. In contrast, ΔV appeared to reflect a different dimension of rhythm, though the authors did not elaborate on its specific function. As such, ΔV remains less clearly interpreted, yet continues to be used as a complementary metric in rhythm analysis.

By providing quantifiable measures, these rhythm metrics have enabled a more systematic and comparative analysis of rhythmic typologies across languages, refining earlier perceptual classifications of rhythm. Taking a different approach to rhythm analysis,

Low et al. (

2000) introduced the Pairwise Variability Index (PVI), which quantifies the degree of durational variability between successive speech units. Unlike the metrics proposed by

Ramus et al. (

1999), which focused on global interval variability, the PVI emphasizes local timing contrasts, offering an alternative lens for examining rhythmic patterns. The PVI is calculated separately for vocalic (vowel) and consonantal intervals within an utterance, capturing differences in rhythmic timing patterns. The formula for the PVI is as follows:

where

m represents the total number of measured intervals, and

dk and

dk+1 denote the durations of two successive intervals. The absolute difference between them is normalized by dividing by their mean duration.

Grabe and Low (

2002) expanded on these metrics, applying both normalized Pairwise Variability Index (nPVI) and raw Pairwise Variability Index (rPVI) to a range of languages, including stress-timed (e.g., English, Dutch), syllable-timed (e.g., French, Spanish), and mora-timed (e.g., Japanese) languages. The nPVI normalizes for speech rate by dividing the absolute duration differences between successive vocalic intervals by their mean duration, ensuring comparability across utterances of varying speeds. However, it is not entirely immune to rate-related effects. Variations in articulation tempo, vowel reduction, or prosodic phrasing can still affect the relative timing of vowels, introducing rhythmic variability that may be reflected in nPVI values despite normalization (

Arvaniti, 2009;

White & Mattys, 2007). In contrast, rPVI remains unnormalized, directly measuring duration variability without accounting for speech rate. Their findings confirmed higher nPVI values in stress-timed languages, moderate values in rhythmically indeterminate languages (e.g., Catalan, Polish), and lower values in syllable-timed languages. Interestingly, they noted that Japanese, traditionally categorized as mora-timed, did not occupy a distinct rhythmic space, but rather overlapped with syllable-timed patterns in certain contexts, challenging traditional classifications.

Arvaniti (

2009) highlights that %V, ΔV, ΔC, and nPVI can be influenced not only by speech rate and segmental properties, but also by prosodic phrasing, which complicates their use as strict typological indicators. However, subsequent rhythm studies have shown that some of these confounds can be mitigated—for instance, by marking the boundaries of intonational phrases (IPs), avoiding PVI calculation across phrase boundaries, and excluding final syllables of IPs, which tend to be lengthened (

White & Mattys, 2007). While segmental variability is a natural part of what rhythm metrics aim to capture, there remains ongoing debate over whether rhythm exists independently of segmental characteristics. As Arvaniti and others note, such independence would be difficult to determine in languages like English that exhibit vowel reduction and phonemic length but may be more assessable in typologically distinct systems with lexical stress but fewer confounding segmental features. Nevertheless, these metrics remain widely applied in rhythm studies, particularly in research on World Englishes and L2 varieties, where rhythm is analyzed as a continuum rather than as a rigid classification (

Grabe & Low, 2002;

Mok & Lee, 2008). Since this study investigates sociolectal rhythm variation within PhE, rather than attempting to classify it into a binary rhythmic category, these measures remain valuable for capturing differences in phonotactic and durational variability across speaker groups.

Building upon these studies,

White and Mattys (

2007) conducted a comparative evaluation of rhythm metrics, including nPVI, rPVI, ΔV, ΔC, %V, and rate-normalized measures such as VarcoV (

White & Mattys, 2007) and VarcoC (

Dellwo, 2006).

2 They found that while some interval measures, such as ΔV and ΔC, were highly influenced by speech rate, nPVI was particularly effective in distinguishing between stress-timed and syllable-timed languages. Their study reinforced the claim that nPVI is a reliable indicator of rhythmic differences, but they also cautioned against a rigid classification of languages into distinct rhythmic categories. Instead, they highlighted the role of gradient variation, where languages exhibit rhythmic tendencies rather than absolute classifications. Furthermore, their findings suggest that while stress-timed languages generally have higher nPVI values, certain factors, such as phonotactic constraints and segmental properties, can influence rhythmic outcomes, making it necessary to interpret rhythm metrics within the broader phonological context of each language. The adoption of rhythm metrics has not only enabled researchers to objectively classify languages along a rhythmic continuum, but has also highlighted the interplay of linguistic features underlying these patterns. For example, ΔV and ΔC emphasize the influence of syllable complexity and vowel reduction, which are key factors in distinguishing stress- and syllable-timed rhythms. Languages with complex syllable structures and significant vowel reduction, such as English, exhibit higher rhythmic variability, whereas languages with simpler syllable structures and minimal reduction, such as Spanish, align with syllable-timed characteristics.

In terms of localized English varieties,

Tan and Low (

2014) further explored rhythm metrics by analyzing Malaysian English (MalE) and Singapore English (SgE) using the Pairwise Variability Index (PVI) and VarcoV to quantify rhythmic differences. Their study provided empirical acoustic analysis, moving beyond previous impressionistic observations of MalE rhythm. The findings revealed that MalE aligns more strongly with syllable-timed rhythms than SgE. In both read and spontaneous speech, MalE speakers exhibited less vowel reduction, resulting in more stable syllable durations and a greater tendency toward syllable-timed rhythmic patterns. Conversely, SgE speakers exhibited higher vowel reduction rates, making their rhythm less strictly syllable-timed than MalE, though still distinct from stress-timed languages like British English.

Moreover, their syllable-based analysis of specific utterances confirmed that MalE speakers retained fuller vowels, whereas SgE speakers typically reduced them. This trend was observed consistently across both read and spontaneous speech, reinforcing the conclusion that MalE follows a stronger syllable-timed rhythmic pattern than SgE. While SgE incorporates stress-timed elements, it does so through phonological restructuring influenced by British English norms, particularly in formal education and media exposure. However,

Tan and Low (

2014) observed that the rhythmic differences between MalE and SgE are smaller than those between SgE and British English, suggesting that both varieties remain largely syllable-timed but exist on a rhythmic continuum rather than in discrete categories.

These findings underscore the effectiveness of quantitative rhythm metrics in capturing prosodic distinctions across nativized English varieties and highlight the role of phonological variation and vowel reduction patterns in shaping rhythmic characteristics.

1.3. Research Gap

Studies on rhythm in nativized English varieties, such as MalE and SgE, have employed rhythm metrics like %V, ΔV, ΔC, and the Pairwise Variability Index (PVI) to examine rhythmic tendencies across different linguistic contexts. These investigations reveal significant insights, such as MalE’s alignment with syllable-timed rhythms and SgE’s incorporation of stress-timed features, reflecting the influence of cultural, educational, and linguistic ecologies. However, these studies often treat MalE and SgE as homogeneous systems, without accounting for the internal variation that arises from sociolinguistic factors like socioeconomic status, education, and linguistic exposure.

In contrast, PhE operates within a more stratified sociolinguistic framework, shaped by the Philippines’ multilingual ecology and its unique sociolectal distinctions. As mentioned earlier,

Tayao’s (

2004) framework categorizes PhE into acrolect, mesolect, and basilect varieties, reflecting varying levels of proficiency and alignment with stress-timed and syllable-timed patterns. This stratification provides an opportunity to explore how rhythm varies across sociolects, offering a more granular understanding of PhE’s prosody. Despite this potential, research on PhE’s rhythmic properties remains sparse, and existing studies often overlook the impact of sociolectal variation on prosodic features like rhythm.

Furthermore, while rhythm metrics have proven effective in distinguishing between stress-timed and syllable-timed languages, their application to sociolectal variation within a single English variety remains underexplored. Existing studies have investigated rhythmic variation in dialects and contact varieties of English (e.g.,

Clopper & Smiljanic, 2015;

Carter, 2005;

Enzinna, 2016;

Torgersen & Szakay, 2012), as well as in regional varieties of Spanish and French (e.g.,

O’Rourke, 2008;

Kaminskaïa et al., 2015). These works provide useful precedents for examining rhythm beyond typological classification, yet few have focused on stratified sociolects within World Englishes.

Tayao’s (

2008) research on PhE has focused on segmental and suprasegmental features, such as phonological substitutions and vowel reduction, without systematically analyzing how rhythm interacts with social and educational factors across the PhE acrolect, mesolect, and basilect. Given that multilingual individuals often develop rhythmic flexibility to accommodate different linguistic contexts, the present study contributes to understanding how rhythmic adaptation serves as an index of sociolectal identity in a multilingual society. This gap in the literature limits our understanding of how PhE’s rhythm reflects its multilingual and sociocultural context, as well as its place within the broader continuum of stress- and syllable-timed rhythms observed in World Englishes.

By addressing these gaps, this study extends the application of rhythm metrics to analyze the sociolectal variations of PhE’s rhythm. Unlike studies on MalE and SgE, this research emphasizes the role of sociolectal stratification in shaping rhythmic tendencies, offering new insights into how linguistic and social diversity influence the prosody of nativized Englishes. Additionally, by situating speech rhythm within the broader discourse on linguistic identity and multilingualism, this study reveals how speakers navigate and express their social affiliations through rhythmic variation, thereby contributing to discussions on identity formation in multilingual contexts.

1.4. The Current Study

This study addresses the research gap by applying quantitative rhythm metrics to analyze the rhythmic features of PhE across its sociolects. Metrics such as %V (percentage of vocalic intervals), ΔV and ΔC (standard deviation of vocalic and consonantal intervals) from

Ramus et al. (

1999), along with nPVI (normalized Pairwise Variability Index) from

Grabe and Low (

2002) are employed to classify PhE’s rhythm.

These tools enable the investigation of the interaction between stress-timed and syllable-timed influences in PhE, which emerges from language contact between English and Filipino. English, a stress-timed language, exhibits uneven syllable durations, vowel reductions, and alternating patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables. In contrast, Filipino—the standardized form of Tagalog—is largely syllable-timed, characterized by consistent syllable durations, minimal vowel reduction, and a tendency to maintain clear segmental articulation regardless of stress. This classification has been empirically validated in a computational rhythm analysis by

Guevara et al. (

2010), which demonstrated that Filipino patterns closely with other syllable-timed languages such as French and Spanish. Given the distinct rhythmic properties of English and Filipino, the influence of these languages on PhE rhythm may vary across sociolects. PhE acrolect speakers with greater exposure to English are expected to exhibit stress-timed patterns, while PhE basilectal speakers may retain syllable-timed features influenced by Filipino.

1.4.1. Research Questions:

This study addresses the following research questions:

A. What are the rhythmic characteristics of the PhE acrolect, mesolect, and basilect sociolects?

Examined through rhythm metrics (%V, ΔV, ΔC, nPVI, rPVI) derived from recorded speech samples.

Analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD to determine statistically significant rhythmic differences across sociolects.

B. How do phonological processes such as vowel reduction, epenthesis, and consonant cluster simplification shape rhythmic variation across PhE sociolects?

C. How do the rhythmic properties of PhE sociolects compare to established stress-timed and syllable-timed languages?

By addressing these questions, the study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of rhythm as a sociolinguistic marker in nativized Englishes and sheds light on how speakers navigate rhythmic variation across social groups in multilingual settings.

1.4.2. Hypotheses

Drawing on previous studies on rhythm typology and phonotactics (e.g.,

Grabe & Low, 2002;

Ramus et al., 1999;

Tayao, 2008), this study proposes the following hypotheses regarding the rhythmic characteristics of Philippine English (PhE) sociolects. For Research Question A, it is expected that the rhythmic patterns of PhE sociolects will reflect distinct timing tendencies. The PhE acrolect is hypothesized to exhibit lower %V, higher nPVI, and greater ΔV and ΔC values, reflecting a stress-timed rhythm influenced by vowel reduction and more complex syllable structures. In contrast, the PhE basilect is expected to show higher %V, lower nPVI, and reduced ΔV and ΔC values, consistent with a syllable-timed rhythm characterized by minimal vowel reduction and simpler phonotactics. Situated between these extremes, the PhE mesolect is anticipated to display intermediate values across the rhythm metrics, reflecting its hybrid phonological profile.

For Research Question B, certain phonological processes—namely, vowel reduction, epenthesis, and consonant cluster simplification—are expected to be associated with rhythmic tendencies across sociolects based on descriptive patterns rather than statistical correlations. Vowel reduction is expected to be most frequent in PhE acrolectal speech, contributing to shorter vocalic durations and greater variability, as reflected in the lower %V and higher nPVI. Epenthesis, or the insertion of vowels within consonant clusters, is anticipated to occur more often in PhE basilectal speech, leading to increased %V and more regular vowel timing. Meanwhile, consonant cluster simplification is expected to emerge more prominently in PhE mesolectal and basilectal speech, potentially contributing to lower ΔC values by reducing the variability of consonantal timing.

For Research Question C, the rhythmic characteristics of PhE sociolects are hypothesized to align with typological patterns observed in stress-timed and syllable-timed languages. PhE acrolect is expected to resemble stress-timed languages such as English, given its greater timing variability and phonotactic complexity. PhE basilect is predicted to align more closely with syllable-timed languages such as Spanish or Tagalog, due to its more stable syllable timing and limited vowel reduction. PhE mesolect, in turn, is anticipated to reflect a mix of rhythmic features, situating it along a continuum between the two prosodic types. These hypotheses offer a structured framework for interpreting the study’s findings and for situating rhythmic variation within broader models of sociophonetic identity in nativized Englishes.