1. Introduction

In Slavic languages, the grammatical aspect is explicitly coded by aspectual morphemes, and it manifests itself as the perfective (

pfv) and imperfective (

ipfv) opposition, presented in (1).

| (1) | čytala | pročytala | Ukrainian |

| | čytała | pročytała | Belarusian |

| | čitala | pročitala | Russian |

| | čítala | prečítala | Slovak |

| | jsem četla | jsem přečetla | Czech |

| | czytałam | przeczytałam | Polish |

| | brala sem | prebrala sem | Slovene |

| | čitala sam | pročitala sam | Serbian |

| | čitala sam | pročitala sam | Croatian |

| | četoh | pročetoh | Bulgarian |

| | čitav | pročitav | Macedonian |

| | read.ipfv.1sg.f | read.pfv.1sg.f | |

Pfv verbs typically describe completed, temporally delimited events and

ipfv verbs refer to unbounded eventualities (

Smith, 1991;

Filip, 1999,

2017;

Borik, 2006;

Grønn, 2015; a.o.). In spite of significant variation in the use and meaning of the

pfv and

ipfv across Slavic, most studies on the Slavic aspect have focused on a single language.

Dickey (

2000,

2015,

2018a,

2018b,

2020) provides a comprehensive comparative framework for analyzing Slavic grammatical aspect, highlighting differences in the use of perfective and imperfective aspects across various contexts, such as habitual actions, general-factual statements, imperatives, and performatives. His micro-typology, termed the East–West aspect division, systematizes these differences. Building on this line of research, we explore the variation in the use and interpretation of the perfective aspect in negated past tense contexts across East and selected West and Southwest Slavic languages. East Slavic uniquely interprets the perfective aspect in these contexts as indicating that an agent either planned but failed to realize the event or initiated it but failed to complete it. In contrast, West and Southwest Slavic allow interpretations where the agent denies the event’s existence at any past time. We propose a novel formal analysis of this variation, adopting the framework of

Fábregas and González (

2020), where negation operates either high (¬TP), as sentential negation, or low (¬vP), over the event domain. We argue that in East Slavic, the interaction of the perfective aspect with past tense restricts negation to the low event domain, giving rise to the inhibited event reading. This is due to the fact that the semantics of the

pfv aspect in East Slavic is analogous to that of specific indefinites in the nominal domain (cf.

Fodor & Sag, 1982;

Diesing, 1992;

Schwarzschild, 2002).

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 1 introduces and motivates the research question and summarizes the main claims of this study.

Section 2 overviews the relevant literature on the interaction of aspect and negation in East and West Slavic.

Section 3 presents the methodology and key findings of an online acceptability rating survey on the variation in the interaction of aspect and negation across East, West, and Southwest Slavic languages.

Section 4 outlines the theoretical framework adopted in this study. Based on

Fábregas and González (

2020), this section introduces the distinction between high and low negation and discusses how these positions interact with aspect and tense in Slavic languages. It also develops a formal account of the variation, proposing that the semantics of the perfective aspect in East Slavic parallels that of specific indefinites in the nominal domain. It explains, formally, how the semantics of the perfective aspect in East and West Slavic constrains its interaction with negation in past tense contexts. Finally,

Section 5 concludes this paper by summarizing the findings and their implications for cross-linguistic research on aspect and negation. This section also identifies directions for future research, particularly regarding the broader typological significance of the observed patterns.

2. Aspect and Negation in East and West Slavic

Dickey and Kresin (

2009) compare aspectual usage in contexts with negation in Russian and Czech narrative texts. Their claim is that negation can be used with

pfv verbs in Russian only when the temporal definiteness of the past situation is satisfied.

Dickey and Kresin (

2009, p. 13) follow

Forsyth (

1970, pp. 103–104), who argues that in Russian, a negated

pfv verb signals the “[n]on-performance of a potential single action at a specific juncture” and he exemplifies it by means of the context presented in (2).

| (2) | Načal’nik | šagnul | k | arestovannomu |

| | chief | stepped | toward | prisoner |

| | i | vdrug | rvjaknul: | - Vstat’! |

| | and | suddenly | bellowed: | - Stand up! |

| | ‘The chief stepped toward the prisoner and bellowed: “Stand up!”’ |

| | Arestovannyj | ne | poševelilsja. | |

| | Prisoner | not | stir.pfv | |

| | ‘The prisoner did not stir.’ |

In this example, the chief orders the prisoner to stand up. The prisoner’s not reacting to this order happened right after the order was made. Therefore, the event of standing up was expected in this situation. In other words, in the scenario in (2), there was a specific situation (the situation is understood as an event instantiated in time) in which the prisoner was expected to stand up, and what is negated is the failure of the expected event to be realized at a specific point in time. Another example of a scenario in which a negated

pfv verb is used in Rus to talk about a past event that failed to occur at a specific point in time is shown in (3), based on

Dickey and Kresin (

2009, p. 29).

| (3) | Na lice D’jakova mel’knula grimasa. No on ničego ne skazal.pfv, tol’ko skosil glaza na svoego načal’nika, točno priglašaja ego ubedit’sja, s kem on, D’jakov, imeet delo, a možet, ožidaja, čto tot sam čto-libo skažet. No čelovek s èskimosskim licom ničego ne skazal.pfv, gruzno podnjalsja i vyšel. |

| | (Rus; Rybakov, 1988, p. 121) |

| | ‘A grimace flashed across D’jakov’s face. But he did not say anything, he only glanced at his superior, as if inviting him to see for himself who he—D’jakov—was dealing with, and perhaps expecting him to say something himself. But the man with the Eskimo face did not say anything, he got up awkwardly and went out.’ |

In this context, D’jakov was expected to say something but he did not. So, also in this scenario, there was a specific situation in which the event was expected to happen but failed to be realized.

Dickey and Kresin (

2009) conclude that the

pfv aspect in negative contexts in Russian expresses the failure of a past action to occur at a specific juncture in time. If this condition is not satisfied, Russian uses the

ipfv even if the negated past event was temporally delimited, as exemplified by

Dickey and Kresin (

2009, p. 40) in (4a and b) for Russian and Czech, respectively.

| (4) | a. Mark Aleksandrovič vsegda vydeljal Sonju sredi drugix svoix sester, ljubil i žalel ee, osobenno bespomoščnuju sejčas, kogda ot nee ušel muž. I Sašu ljubil. Za čto pridralis’ k mal’čiku? Ved’ on čestno skazal, a emu lomajut dušu, trebujut raskajanija v tom, čego ne soveršal.ipfv. |

| | (Rus; Rybakov, 1988, p. 14) |

| | b. Mark dával vždycky přednost Soně před ostatními sestrami, měl ji rád a litoval ji pro její bezradnost, zvlášt’ ted’, když od ní odešel muž. I Sašu měl rád. Proč si na toho chlapce tak zasedli? Vždyt’ mluvil pravdu, a oni mu křiví charakter, chtějí po něm, aby si sypal popel na hlavu za něco, co neudělal.pfv. |

| | (Cze; Rybakov, 1989 translated by Tafelová, p. 19) |

| | ‘Mark Aleksandrovič always singled Sonja out from his other sisters, loved and pitied her, especially now, helpless as she was since her husband had left her. He also loved Saša. Why were they picking on the boy so much? He had told the truth, but they were crushing his soul, demanding repentance for something he had not done.’ |

In (4), unlike in (2) and (3), the negated event was not expected or planned. What is negated is the mere existence of the event at any point in time.

Similarly to

Dickey and Kresin (

2009),

Leinonen (

1982, pp. 256–259) postulates that the negated

pfv aspect in Rus indicates the presence of a “precondition”, i.e., an expectation of the corresponding affirmative predicate at a particular juncture in the discourse.

Mehlig (

1999, p. 192) proposes that negated

pfv predicates in Russian refer definitely (i.e., they refer to situations about which the speaker assumes that the listener knows).

More recently,

Kagan (

2020) and

Copley and Kagan (

2023) have noticed that in a court scenario presented in (5) in Rus, Anna is accused of killing Ivan, and the speaker denies it by using a neg

ipfv verb, even though a completed past event is discussed.

| (5) | RUS | Anna | ne | ubivala/#ubila | Ivana. |

| | | Anna | neg | killed.ipfv/pfv | Ivan |

| | | ‘Anna did not kill Ivan.’ |

They point out that when the perfective is used in (5), the context sounds like a confession. The speaker is saying that Anna might have attempted to kill Ivan, but she failed. Alternatively, she could have planned the murder but ultimately decided against it (cf.

Paducheva, 2013). If an attempt was made, it could be said that the killing event was initiated but left incomplete.

Copley and Kagan (

2023) account for this observation within the force-theoretic framework of

Copley and Harley (

2015). Perfective verbs presuppose the existence of a force X (plan, intention, and expectation) which, with no external intervention, would bring about the event E, denoted by the perfective predicate, including its result state R. When a

pfv statement is negated, it is either the X (plan) but not E → R that is preserved under the negation. Alternatively, the chain X (plan) → E is preserved under negation, but R fails to be realized. A potential problem for this claim is that the

pfv aspect should trigger the same presupposition of intention/plan in future tense contexts in Russian contrary to fact. Consider the following offering context:

| (6) | a. | #If you want I am visiting you on Monday. |

| | b. | #If you want I am going to visit you on Monday. |

| | c. | If you want I will visit you on Monday. |

As observed by

Copley (

2009), in offering contexts, future forms presupposing the existence of a plan are implausible in English. When we make an offer, our addressee should have the possibility of either accepting or rejecting it. This implies that we cannot offer future actions which are already settled or planned at the moment of speaking. If it is true that the

pfv in Russian presupposes pre-arrangement, it should be pragmatically implausible in offering contexts contrary to fact; see (7).

| (7) | Esli | xočeš’, | ja pridu | k | tebe | v | ponedel’nik. |

| | if | you want | come.pres.pfv | to | you | on | Monday |

| ‘If you want I will visit you on Monday.’ |

This implies that the presupposition of the existence of a plan arises when the

pfv is used in negative past tense contexts, suggesting that it is related to the interaction of negation, aspect, and past tense. Another puzzling fact is that the confession effect in a court scenario under consideration in (5) is available in Russian, but it does not arise in analogous negative past tense perfective contexts in Polish. In fact, in Polish, the court scenario accusation–denial context would most naturally trigger the use of the

pfv aspect, as shown in (8).

| (8) | PL | Anna | nie | zabiła/#zabijała | Jana. |

| | | Anna | neg | killed.pfv/ipfv | Jan |

| | | ‘Anna did not kill Ivan.’ |

Inspired by this observation, we broadened a comparative perspective to all the East Slavic languages, including Ukrainian, Belarussian, and Russian, and selected West and Southwest Slavic languages, including Polish, Czech, Slovenian, and Serbian, and we conducted an online survey testing the acceptability of pfv and ipfv aspectual forms in accusation–denial past tense contexts with negation.

3. The Study

In our study, we constructed ten scenarios in which the subject is accused of some past action, but they deny it using negation. The original list of scenarios was prepared in English, and it was translated into Polish (Pol), Czech (Cze), Russian (Rus), Belarusian (Bel), Ukrainian (Ukr), Slovenian (Slv), and Serbian (Srp), as exemplified in

Table 1 (the full set of tested contexts is provided in the

Supplementary Materials).

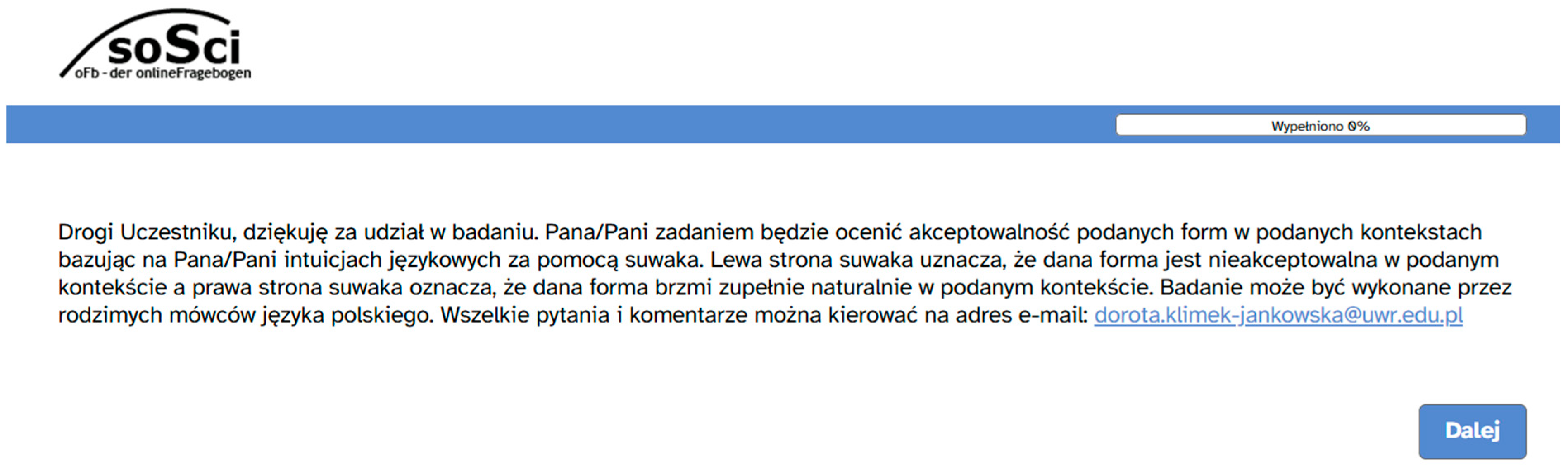

Each context contained a gap, and the participants saw two options for verbs (

pfv and

ipfv). The order of options was counterbalanced in that 50% of the contexts contained

pfv-ipfv verbs, and the other 50% of the contexts contained

ipfv-pfv verbs. Next to each aspectual form, there was a slider, and the participants were instructed to use the slider to rate how acceptable the two forms were in the provided context. The numerical values on the slider ranged from 0 to 100. The participants were instructed that the left side of the slider means unacceptable, and the right side of the slider means acceptable. The survey was administered on the SoScie Survey. The instructions were given in the native language of the participants, as shown in

Figure 1.

The English translation of the instructions is provided in (9).

| (9) | Dear Participant, thank you for participating in the study. Your task will be to assess the acceptability of the given forms in the given contexts based on your linguistic intuitions using the slider. The left side of the slider means that a given form is unacceptable in the given context, and the right side of the slider means that the given form sounds completely natural in the given context. The test can be performed by native speakers of ……………… only. |

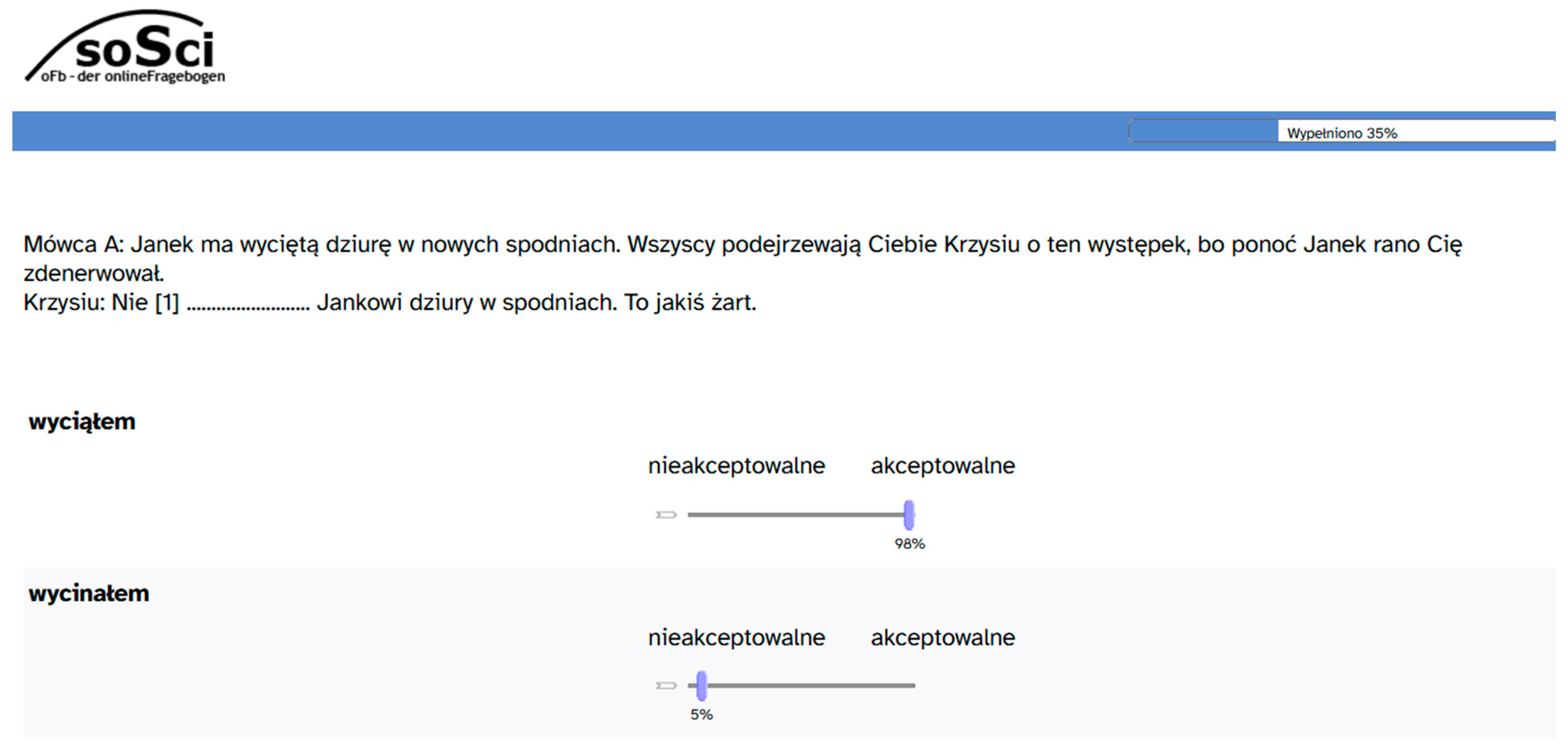

An example trial is presented in

Figure 2.

The English translation of the Polish context is provided in (10).

| (10) | Speaker A: John has a hole cut out in his new pants. Everyone suspects you, Chris, of this crime, because John apparently upset you in the morning. |

| | Chris: No, I did not [1] .............. holes in John’s pants. You must be kidding me. |

| | cut out.pfv |

| | cut out.ipfv |

Participants were recruited through social media and Prolific. Responses were collected on SoSci Survey. Only native speakers of the tested language were invited to participate. The tested contexts were mixed with filler contexts containing adverbs of quantification, multiplicatives, and the adverbs

never and

ever to distract the participants from the goal of this study and to prevent the participants from developing a strategy in providing judgments. Among the fillers, there were unacceptable fillers, which helped us determine if the participants filled in the test attentively and whether they had native speaker judgments. Deviant responses (the ones in which unacceptable fillers were rated as acceptable) were filtered out. We collected responses from 30 participants for each language. The acceptability ratings for the

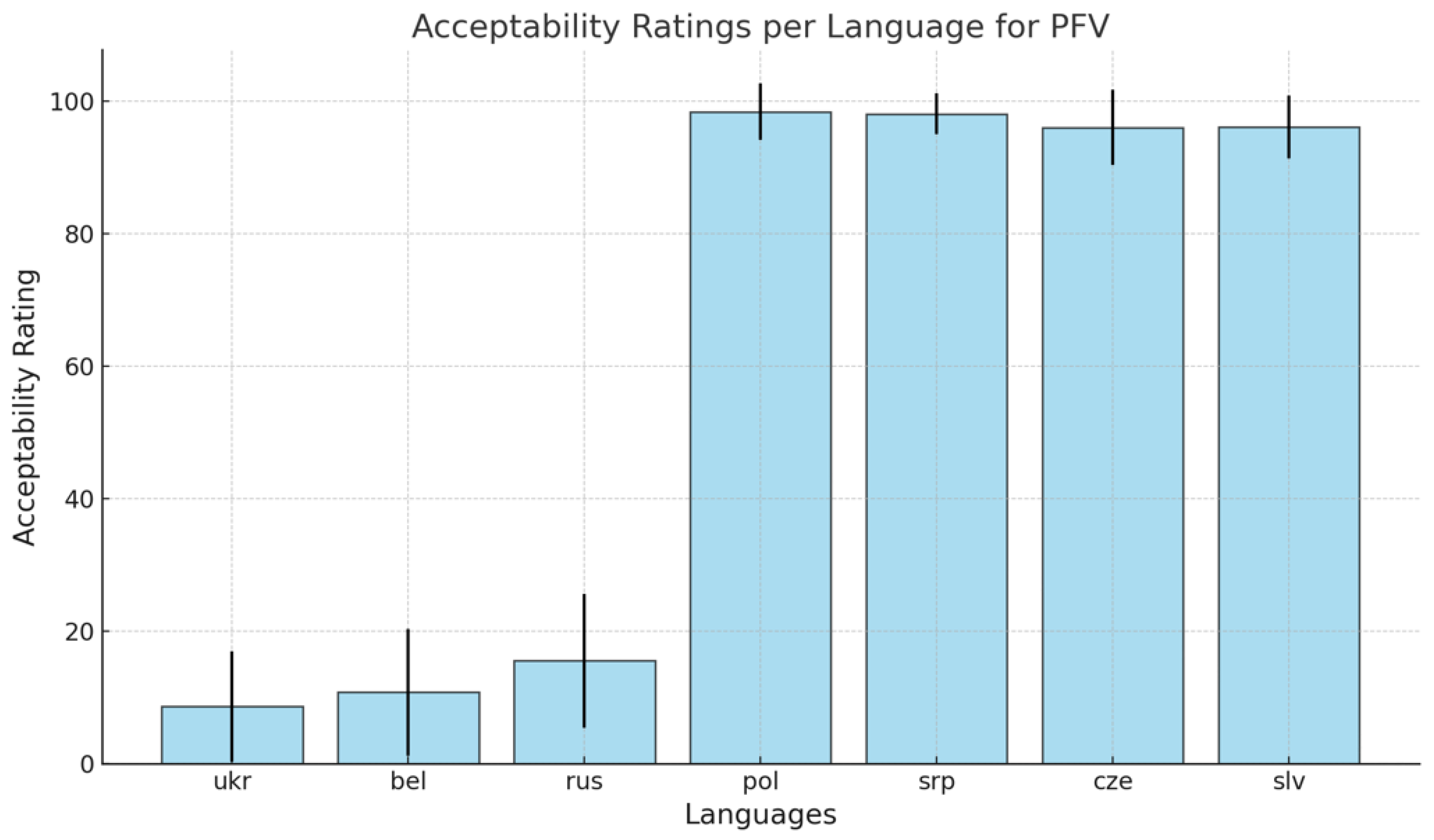

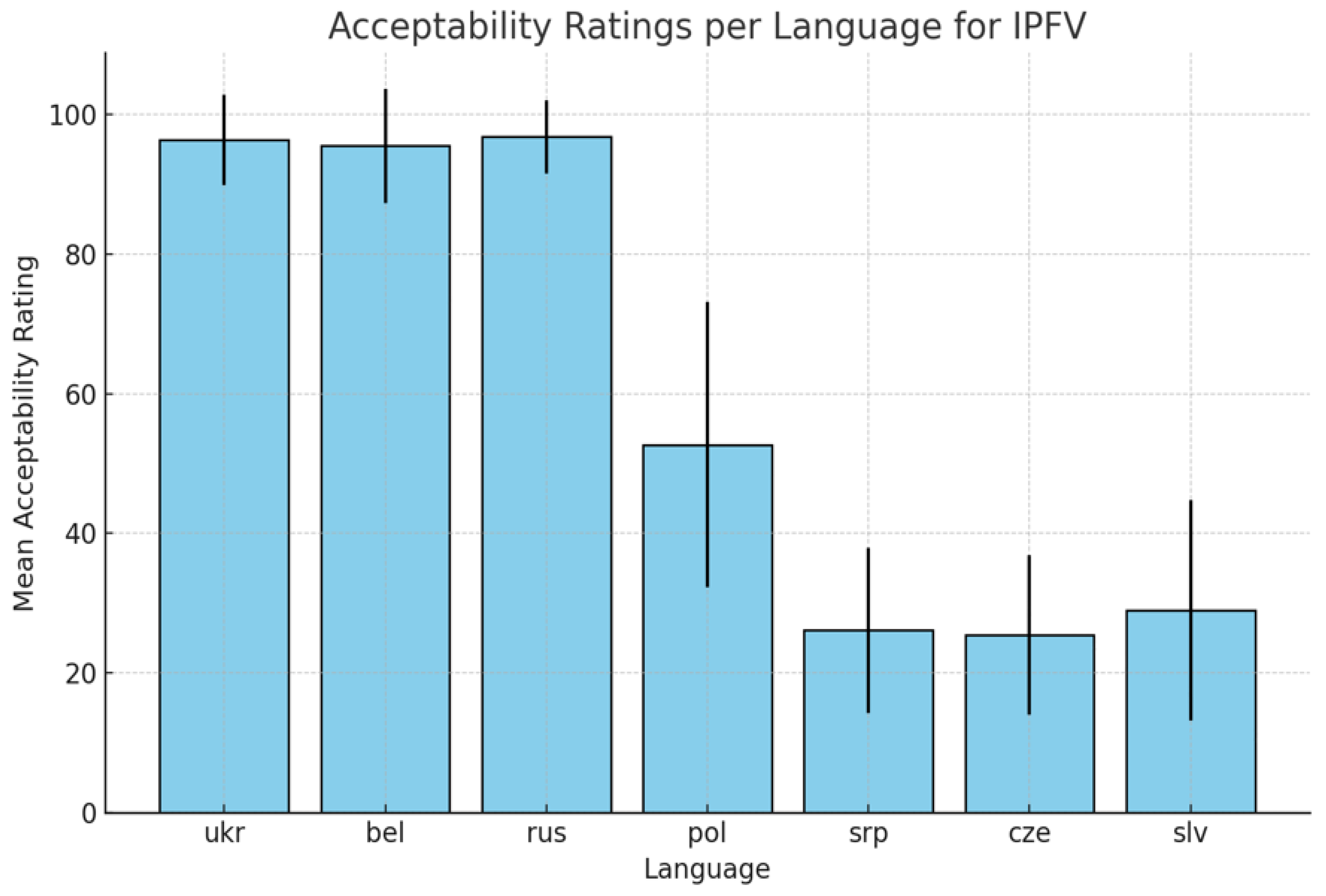

pfv forms are provided in

Table 2 and

Figure 3, and the acceptability ratings for the imperfective forms are provided in

Table 3 and

Figure 4 (the full set of collected data, the R script and the full statistics report can be found in the

Supplementary Materials).

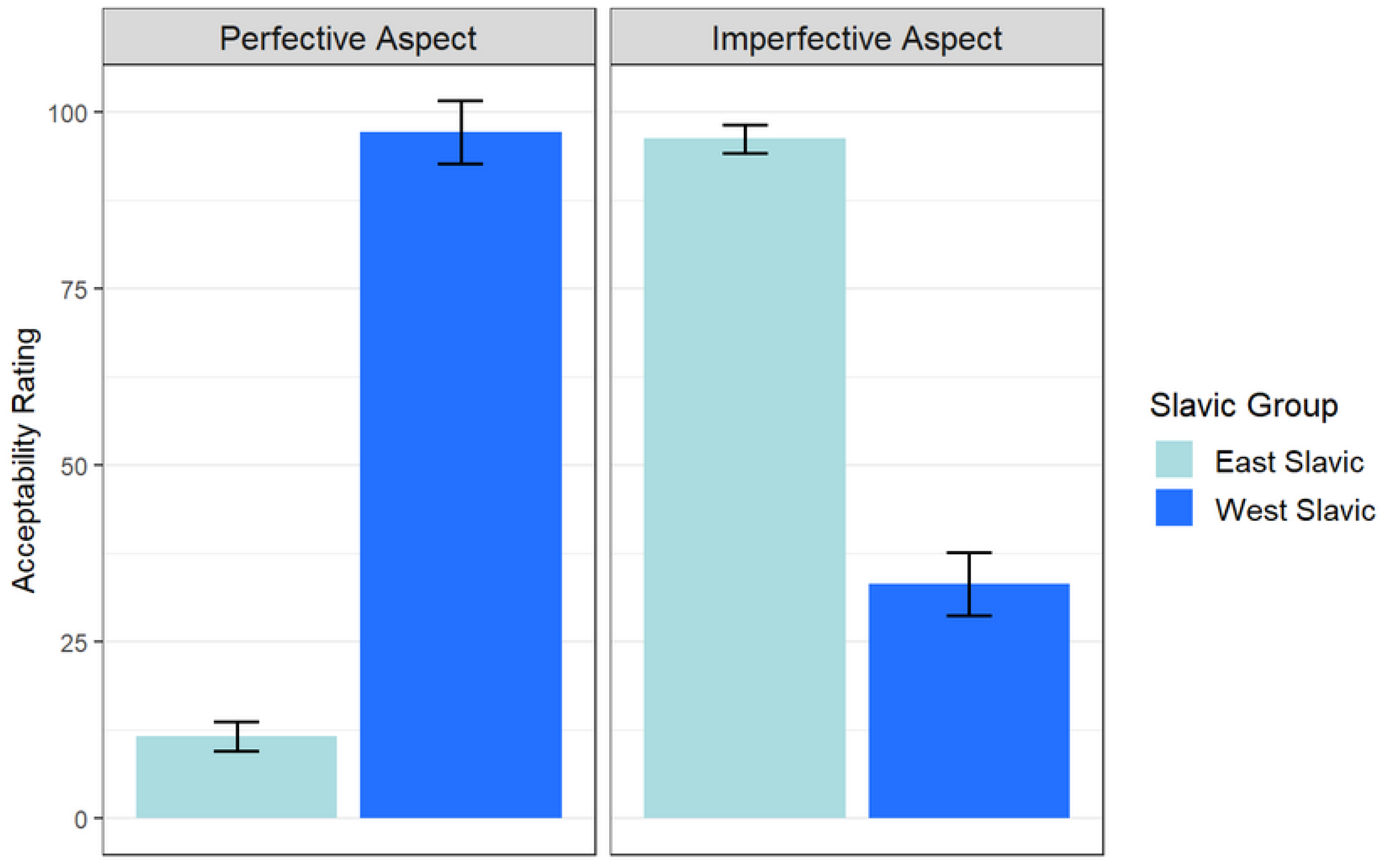

In order to provide a statistical analysis of the survey results, a linear mixed-effects model was fitted with Acceptability Rating as the outcome variable and Aspect, Slavic Group, and their interaction as predictors. The random structure consisted of the random intercept for Participant and Item, as well as the random slope of Slavic Group for Item. This was the maximal structure that allowed for correct model convergence. The predictors were sum-coded to facilitate the interpretability of the main effect and interaction coefficients: Aspect (pfv = 1/ipfv = −1) and Slavic Group (east = 1/west = −1). There was a significant main effect of both Aspect (β = −5.16, SE = 0.368, t(4166) = −14.019, p < 0.001) and Slavic Group (β = −5.629, SE = 1.155, t(9) = −4.875, p = 0.001). The main effects were qualified by a statistically significant interaction between the two factors (β = −37.117, SE = 0.368, t(4166) = −100.848, p < 0.001).

An inspection of the model-predicted marginal means (see

Figure 5) revealed that the interaction consisted of the opposite effect of Aspect on the responses in the different levels of Slavic Group.

Whereas the estimated ratings of trials with the perfective aspect were close to full acceptability for speakers of West Slavic languages (est. mean = 97.14), speakers of East Slavic languages rated them as mostly unacceptable (est. mean = 11.65). The opposite pattern was observed for trials with the imperfective aspect: West Slavic respondents rated them as somewhat unacceptable (est. mean = 33.23), while East Slavic speakers rated them as largely fully acceptable (est. mean = 96.20)

1.

The results show a dichotomy between the East Slavic languages (Bel, Ukr, and Rus), which strongly prefer the imperfective aspect in the tested accusation–denial negative past tense contexts, and West (Pol, Cze) and Southwest Slavic (Srp and Slv) on the other hand, which strongly prefer the perfective aspect in these contexts. The preference for the imperfective aspect in East Slavic in contexts that talk about telic past events is surprising. The question is what blocks the pfv aspect in East Slavic (but not in West and Southwest Slavic) in the tested contexts.

In order to account for the results, we need to broaden our understanding of the semantics of the perfective aspect and its interaction with negation in East and West Slavic. We will first briefly discuss the relevant literature on the variation in the semantics of aspect in Slavic languages. Then, we will introduce relevant cross-linguistic facts on two types of negation and their semantic differences. With this background in mind, we will present our formal analysis of the investigated problem.

4. Towards a Formal Account

4.1. Variation in the Semantics of Aspect Across Slavic

In the earlier literature, most scholars tend to advocate different meaning components of the

pfv and

ipfv aspects to account for the variation in its use across Slavic (see

Dickey, 2000,

2015;

Mueller-Reichau, 2018;

Klimek-Jankowska, 2020,

2022;

Gehrke, 2022,

in press).

Dickey (

2000,

2015) accounts for the differences in the Slavic aspectual system by postulating that in the western aspectual group, the

pfv aspect conveys totality, while the

ipfv aspect expresses quantitative temporal indefiniteness. Conversely, in the eastern aspectual group, the

pfv aspect is associated with temporal definiteness, and the

ipfv with qualitative temporal indefiniteness, where temporal definiteness refers to a situation that is “uniquely locatable in a context” and temporal indefiniteness relates to the absence of an assignment of an event to a single, unique point in time. Croatian and Serbian as well as Polish, occupy transitional zones, leaning toward the western and eastern types, respectively.

Mueller-Reichau (

2018) attributes the difference in the distribution of grammatical aspects in Czech, Polish, and Russian to the different semantics of the

pfv aspect. More precisely, in all three languages, perfective verbs involve event uniqueness, but in Russian, there is an additional requirement of target state validity. The difference is captured in the formulas presented in (11).

| (11) | a. | [[PFV POL/CZ]] = λPλt∃e[P(e) ∧ e ⊆ t ∧ ¬∃e′[P(e′) ∧ e′ ≠ e]] |

| | b. | [[PFV RU]] = λPλt∃e[P(e) ∧ e ⊆ t ∧ ¬∃e′[P(e′) ∧ e′ ≠ e] ∧ f end(t) ⊆ f target(e)] |

In PL, CZ, and RUS, the perfective requires that the event time is included in the reference time (

e ⊆

t). For the event to be unique, it is required that no event

e′ exists for which the property holds as well and which is not identical to

e. In Russian, there is an additional requirement specified in (

f end(

t) ⊆

f target(

e)), i.e., the reference time is required to end when the target state is in force. This requirement prevents the perfective aspect in Russian from being used in any existential context, which is not the case in Czech and Polish. This is because to meet the condition of target state validity, the event has to have a specific reference time. Both

Dickey (

2000,

2015) and

Mueller-Reichau (

2018) mention temporal definiteness or specific reference time in the context of the Russian

pfv aspect.

Klimek-Jankowska (

2022) argues that the variation in the distribution of the

pfv and

ipfv aspects in general-factual contexts in East and West Slavic arises from the interaction between tense and aspect, with the

pfv being associated with temporal specificity in East Slavic. Similarly,

Gehrke (

in press) explores the idea that the Russian aspect has more tense properties than other Slavic aspects, investigates the role of finiteness in the context of the Russian aspect, and outlines a general research program that has the goal of drawing parallels between individuals, events, and times regarding definiteness in the discussion of the variation in the distribution and meaning of the Slavic aspect. Along these lines, we postulate that in order to account for the observed variation in the distribution of aspects in negative contexts across Slavic we should shift our attention to how the

pfv and

ipfv aspects interact with past tense in East, West, and Southwest Slavic.

4.2. Cross-Linguistic Facts on Two Types of Negation

In our account, we rely on

Fábregas and González (

2020), who discuss Lithuanian contexts (based on

Arkadiev, 2021) in which a neg operator can be used either before an

aux or between an

aux and a participle (see 12), which is related to two different readings.

| (12) | a. | Ne-s-u | miegoj-us-i. |

| | | neg-be-1sg | sleep-ptcp-nom.sg.f |

| | | ‘I have not slept.’ |

| | b. | Es-u | ne-miegoj-us-i. |

| | | be-1sg | neg-sleep-ptcp-nom.sg.f |

| | | ‘I have not slept.’ |

In (12a), the speaker denies that they have the experience of having slept, as in,

It is not the case that I have slept, while (12b) asserts that the speaker now suffers the consequences of an event that was expected to happen but did not, as in,

It is the case that I have not slept. The high negation is the standard sentential negation, where the NegP is generated to the left of the TP (see

Zanuttini, 1997). The low negation has properties that are familiar to the type of interpretations known in the literature as “negative event readings” (see

Stockwell et al., 1973;

Horn, 1989;

Asher, 1993;

de Swart & Molendijk, 1999;

Przepiórkowski, 1999;

Arkadiev, 2015,

2016; a.o.).

Fábregas and González (

2020) argue that the ‘low negation’ gives rise to an inhibited event reading where the subject refrains from realizing the event, as in,

I saw María not kiss the bride, where in fact the speaker saw that María failed to kiss the bride, which was expected in this particular social context. They argue that the low negation is placed below the AspP and above the verbal (event) domain. This is compatible with

Ramchand (

2004), who shows that Bengali possesses two distinct sentential negation markers,

na and

ni, which occur in different morphosyntactic contexts and with different interpretations. According to

Ramchand (

2004),

na is a negative quantifier over events, and when it is used, the time variable is linked via context to some particular time in the past, and the negation merely says that no event of the specified type occurred at that moment. This corresponds to the formula in (13) for the sentence:

John did not eat the mango.

On the other hand,

ni is a negative quantifier that binds the time variable. A sentence with this sort of negation states that for no time at all (in the discourse context) did an event of the specified type occur, corresponding to the formula in (14).

Importantly, only the

na marker, which is a negative quantifier over events, gives rise to an inhibited event reading in Bengali. Along similar lines, we add new data from Venetan (Italo-Romance) varieties, which use the two distinct neg markers

no, appearing before the aux (15a), and

mia, appearing between an

aux and a participle (15b) (cf.

Magistro, 2023), and these positions are related to two different readings.

| (15) | a. | La | Maria | no | la = ga | basà | el | sposo. |

| | | def | Mary | neg | 3sg = have | kissed | def | groom |

| | | ‘Mary did not kiss the groom.’ |

| | b. | La | Maria | la = ga | mia | basà | el | sposo. |

| | | def | Mary | 3sg = have | neg | kissed | def | groom |

| | | ‘Mary did not kiss the groom.’ |

By contrast, low negation is naturally used in contexts in which the event was expected but failed to be realized. In (15b), Mary did not kiss the groom at the wedding ceremony at the time when it was expected. Low negation in Venetan clearly triggers an inhibited event reading. Only the higher negation

no (but not the low negation

mia) asserts that an event did not happen at any time. High negation in Venetan is natural in contexts with negative polarity items like

ever/never, as in (16).

| (16) | a. | No | go | mai | magnà | el | mango. |

| | | Neg | have.1sg | never | eaten | the | mango |

| | | ‘I have never eaten mango.’ |

| | b. | *Go | mia | mai | magnà | el | mango. |

| | | have.1sg | neg | never | eaten | the | mango |

| | | ‘I have never eaten mango.’ |

All these facts allow us to assume, following

Fábregas and González (

2020), that the inhibited event reading in negative contexts arises when the negation acts low over the vP (event domain).

4.3. On Different Merge Sites of Negation and Their Semantics in Slavic

The two negations in Venetan overtly instantiate different NegPs within a single clause. The pre-aux

no occupies a high NegP1, merged over the TP. The post-aux

mia occupies a lower NegP2, merged over the vP (cf.

Zanuttini, 1997;

Zeijlstra, 2004); see (17).

| (17) | [CP [NegP1 [Neg no] [TP [AspP [NegP2 [Neg mia] [vP/VP …]]]]]] |

We propose that the different NegPs are universally available cross-linguistically and languages differ in their PF and LF realization; languages like Venetan use separate items. Slavic languages allow the same negation item to be realized in different NegPs (see

Borsley & Rivero, 1994).

Zeijlstra (

2004) proposes that in Slavic languages that feature the negative concord, the negation operator Op¬ is covertly realized above the TP at LF and takes scope over the entire proposition. We diverge from this standard view and provide evidence that the same negation item can be realized in different NegPs and scope over either the TP or vP/VP in Slavic. Our first argument is based on the interaction of negation with restructuring verbs, such as, for example,

stop, continue, finish, and

try in Slavic languages. We adopt

Cinque’s (

2001) proposal that restructuring verbs are not full lexical verbs but functional heads that directly integrate into a rigidly ordered hierarchy of projections. This means that restructuring always takes place within a single clause. Cinque supports this monoclausal analysis with the strict ordering of multiple restructuring verbs. In Cinque’s hierarchy, conative

try aligns with the predispositional aspect, positioned below the habitual aspect

be used to but above the attempted event predicate.

| (18) | [TP [Asp-HabP be used to [Asp-PredP try [ Asp-TermP stop [Asp-ContP continue ]]]]] |

This ordering is evident in word order constraints, where habitual

be used to must precede

try, while

try precedes an infinitival verb.

| (19) | On | byl | privyk | pytat’sja | delat’ | eto | samostojatel’no | RUS |

| | he | was | used | try | do | this | himself | |

| | ‘He used to try to do things by himself.’ | |

| (20) | *On | pytalsja | byt’ | privyk | delat’ | eto | samostojatel’no | |

| | he | tried | be | used | do | this | himself | |

| | ‘He tried to be used to do it by himself.’ | |

Example (19) is grammatical, whereas (20) is not, confirming that

try is structurally lower than

be used to. This rigid sequencing supports Cinque’s claim that restructuring verbs are functional heads, integrated into a fixed syntactic structure rather than behaving as full lexical verbs.

Try is best understood as a predispositional aspect verb that sits below habitual and expresses an attempted event. Going back to negation, this evidence is crucial to support the necessity of assuming two syntactic positions for negation in Slavic (we use Russian and Polish for illustration), considering the following examples:

| (21) | a. | On | ne | byl | privyk | pytat’sja | delat’ | eto | samostojatel’no. | RUS |

| | | he | not | was | used | try | do | this | himself | |

| | | ‘He used to try to do this by himself.’ | |

| | b. | On | nie | zwykł | próbować | robić | rzeczy | samodzielnie. | | POL |

| | | he | not | used | try | do | things | himself | | |

| | | ‘He did not try to do this by himself.’ | |

| (22) | a. | On | byl | privyk | ne | pytat’sja | delat’ | eto | samostojatel’no. | RUS. |

| | | he | was | used | not | try | do | this | himself | |

| | | ‘He used not to try to do this by himself.’ | |

| | b. | On | zwykł | nie | próbować | robić | rzeczy | samodzielnie. | | POL |

| | | he | used | not | try | do | things | himself | | |

| | | ‘He used not to try to do this by himself.’ | |

| (23) | a. | On | byl | privyk | pytat’sja | ne | delat’ | eto | samostojatel’no. | RUS |

| | | he | was | used | try | ne | do | this | himself | |

| | | ‘He used to try not to do this by himself.’ | |

| | b. | On | zwykł | próbować | nie | robić | rzeczy | samodzielnie. | | POL |

| | | he | used | try | not | do | things | himself | | |

| | | ‘He used to try not to do this by himself.’ | |

The structure in (24) corresponds to the situation in which the speaker negates the fact that someone used to try to do something by himself, meaning “It was not the case that he used to try to do it by himself”. Conversely, (25) corresponds to the situation in which the speaker negates only the act of trying, implying that he had a habit of not trying to do things by himself. Example (26) corresponds to the situation in which he used to try not to do something by himself. These facts suggest that negation can scope over lower portions of the clause and not necessarily over the TP solely.

We propose that, in a monoclausal configuration where

try behaves as a restructuring verb, the three sentences have the following structures:

| (24) | [NegP ne [TP byl [Asp-HabP privyk [Asp-PredP pytat’sja [vP/VP delat’ eto

samostojatel’no ]]]]] |

| (25) | [TP byl [Asp-HabP privyk [NegP ne [Asp-PredP pytat’sja [vP/VP delat’ eto

samostojatel’no ]]]]] |

| (26) | [TP byl [Asp-HabP privyk [Asp-PredP pytat’sja [NegP ne [vP/VP delat’ eto

samostojatel’no ]]]] |

Another argument for the potential low position of negation comes from its interaction with durative adverbs like

for x time (e.g.,

for three hours,

for a long time), which typically attach to the AspP in the syntactic structure (see

Travis, 1988,

1994).

Alexiadou (

1994) acknowledges that while durative adverbs are generally considered AspP-adjoined, there are cases where they might attach higher, potentially at the TP. This happens when durative adverbs are used sentence-initially, and they set the scene, as in:

For three hours, John read the book. In this case,

for three hours could be left-adjoined to the TP. It turns out that durative adverbs may modify negative events. Consider (27) in Russian and Polish:

| (27) | a. | On | ne | skazal | ni | slova | v | tečenie | časa. | RUS |

| | | he | not | say.pfv.pst | no | word | for | duration | Hour | |

| | | ‘He did not say a word for an hour.’ | |

| | b. | Nie | odezwał | się | słowem | przez | godzinę. | | | POL |

| | | not | say.pfv.pst | refl | word.inst | for | hour | | | |

| | | ‘He did not say a word for an hour.’ | |

In (27), the durative adverb scopes above negation, and it describes the duration of a negative event. It is used sentence-finally, which allows us to assume it attaches to the AspP, implying that the negation in its scope is below the AspP. These facts allow us to argue that even though one negation marker, ne, in Slavic languages, it can be realized in high and low NegP, scoping over the TP and vP/VP, respectively. Importantly, both in the contexts with the verb try not to do something and not to do something for an hour, the negated component expresses an inhibited event. In the context with try, the embedded event was attempted but failed to be realized, while in the context with the durative adverbial, the negated event was expected but the subject managed not to do something for an hour.

4.4. Variation in the Composition of the Perfective Aspect and Negation in East and West Slavic

In what follows, we propose a formal account of the obligatory inhibited event reading in East Slavic and not in West and Southwest Slavic.

We assume, following

Ramchand (

2008a,

2008b), that the aspectual head of the AspP combines with the predicate of events in the vP, and it binds the event variable

e introduced by the verbal predicate (in this case, the

l-participle). The aspectual head also introduces a time variable,

t, and establishes the following two types of relations:

Relation 1: t is temporally related to the run time of the event with the perfective situating the run time of the event inside t (τ (e) ⊆ t) and the imperfective situating t inside the run time of the event t ⊆ τ (e).

Relation 2: t is introduced by the AspP and is related to the TP level where t is located before, at, or after the evaluation time t* (by default, it is the speech time).

We claim that it is this second relation that distinguishes between East and West Slavic. It is constituted as an outcome of the interaction between the AspP and TP, in that the anchoring of t to the time axis with respect to t* is taking place at the level of the TP, but the perfective aspect in East Slavic imposes a constraint, and it requires that the t variable it introduces be anchored at a specific point in time (an analogy to specific indefinites in the nominal domain). The difference between East and West Slavic resides in the way the pfv aspect interacts with the past tense.

4.4.1. Negated Past Tense in West and Southwest Slavic

In West and Southwest Slavic, high negation takes scope over the existential quantifier over

t. In such cases, the existence of a time interval instantiating the event in the actual world is denied (¬∃t). In other words, we receive the interpretation that the event under consideration did not happen at any time before the speech time, as shown in (28).

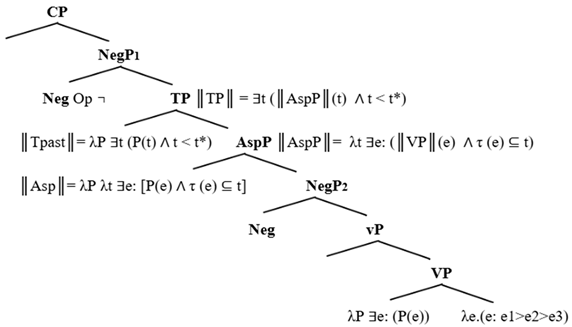

| (28) | ![Languages 10 00078 i001]() |

The notation e: e1 > e2 > e3 corresponds to

Ramchand’s (

2008a,

2008b) event decomposition in the first phase of the derivation (the so-called first-phase syntax), with e1 standing for an initiation subevent, e2 a process subevent, and e3 the result subevent. E1 causes e2, and e2 causes e3. See

Section 5 for more details.

Importantly, Op¬ in the

pfv simple past contexts in West and Southwest Slavic is realized as high negation (¬TP), represented in (17), repeated here as (29).

| (29) | [CP [NegP1 [Neg Op¬ ] [TP [AspP [NegP2 [Neg ø] [vP/VP …]]]]]] |

4.4.2. Negated Past Tense in East Slavic

In East Slavic, we propose that the

pfv aspect affects the anchoring of

t to the time axis in ways analogous to specific indefinites in the nominal domain (cf.

Fodor & Sag, 1982;

Diesing, 1992;

Reinhart, 1997;

Winter, 1997;

Schwarzschild, 2002;

Geist, 2019;

Heim, 2011; a.o.). More precisely, a

t variable introduced at the AspP is bound in an operation of existential closure over a variable

t selected by a choice function. A choice function CH(f) applies to a non-empty set of values and yields a specific member of that set. This is compatible with the formal treatment of specific indefinites proposed by

Schwarzschild (

2002), according to whom specific indefinites involve a pragmatic mechanism reducing the domain of an existential quantifier to a singleton set. We propose that

pfv past tense verbs in East Slavic are interpreted vie existential quantification over

t, with the domain of quantification restricted to a singleton set ∃t

D = {t} (t ∈ {t} ‖AspP‖(t) ∧ t < t*) at the TP. The singleton set {t} is the outcome of the choice function CH(f), which is part of the semantics of the perfective aspect, and it applies to a non-empty set of values of t introduced at the level of the AspP and yields a specific member of that set. This means that

pfv verbs in East Slavic are pretty close to being referential in that the event is anchored to a specific single temporal interval; see (30).

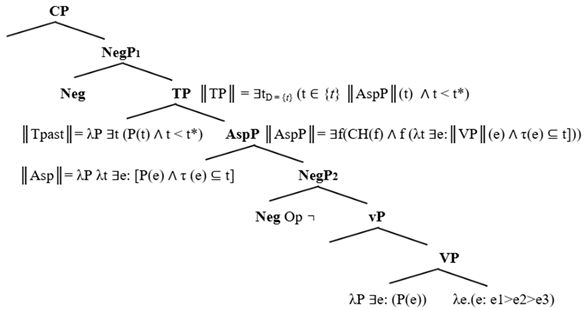

| (30) | ![Languages 10 00078 i002]() |

We claim that the operation of the existential closure of the

t variable selected via a choice function gives rise to the presupposition of the existence of

t (cf.

Diesing, 1992;

Kratzer, 1995).

Following

Stalnaker (

1973), we assume that presupposition is a proposition that both speakers assume to be part of the common ground in a conversation. The common ground consists of shared beliefs or assumptions between participants. According to Stalnaker, when a speaker makes an assertion, they act as if the presuppositions of that assertion are already accepted by all parties. What is presupposed in East Slavic in contexts with perfective past tense verbs is the time/world instantiation of the event. Hence, the event under consideration is, by presupposition, anchored to a specific temporal interval.

2 The presupposition of the existence of

t cannot be canceled by negation (typically, presupposed content cannot be canceled by negation; cf.

Abrusán, 2016). This explains why negated

pfv past tense contexts in East Slavic block high negation and force low negation (¬vP) at LF; see (31).

| (31) | [CP [NegP1 [Neg ø] [TP [AspP [NegP2 [Neg Op¬] [vP/VP …]]]]]] |

One argument for this view comes from the observation that the perfective predicates in East Slavic in past tense contexts are incompatible with the negative polarity adverbs

ever and

never, which are also called non-specific occurrence adverbs.

Ever is used in questions in which the speaker asks if the event happened at least once at any time in the past.

Never states that there has been no time at which the event under discussion happened in the past. Example (32) shows that East Slavic languages obligatorily use the imperfective in contexts with

ever and

never, suggesting that the perfective is blocked in temporally nonspecific contexts (cf.

Kagan, 2010). By contrast, (33) shows that West and Southwest languages use the perfective aspect in contexts with

never and

ever.| (32) | a. | A: | Ty | kali-nebudz’ | lamaŭ | | /*zlamaŭ | drevy? | | | BEL |

| | | | you | ever | break.ipfv.pst | | break.pfv.pst | leg | | | |

| | | | ‘Have you ever broken a leg?’ | | |

| | b. | B: | Ne, | ja | za svaë žyccë | | ne | lamaŭ | /*zlamaŭ | dreva. | |

| | | | no | I | in my life | | not | break.ipfv.pst | break.pfv.pst | leg | |

| | | | ‘No, I have never broken a leg.’ | |

| | b. | A: | Ty | kogda-nibud’ | lomal | | /*slomal | nogu? | | | RUS |

| | | | you | ever | break.ipfv.pst | | break.pfv.pst | leg | | | |

| | | | ‘Have you ever broken a leg? | |

| | | B. | Ja | nikogda | v žizni | | ne | lomal | /*slomal | nogi. | |

| | | | I | never | In life | | not | break.ipfv.pst | break.pfv.pst | leg | |

| | | | ’No, I have never broken a leg in my life.’ | |

| | c. | A: | Ty | koly-nebud’ | lamav | | /*zlamav | nohu? | | | UKR |

| | | | you | ever | break.ipfv.pst | | break.pfv.pst | leg | | | |

| | | ‘Have you ever broken a leg?’ | |

| | | B. | Ni, | naspravdi | v žytti | | ne | lamav | /*zlamav | nohy. | |

| | | | No | | In life | | not | break.ipfv.pst | break.pfv.pst | | |

| | | | ’No, I have never broken a leg in my life.’ | |

| (33) | a. | A: | Už | jsi | někdy | zlomil | /*lomil | nohu? | | CZ |

| | | | already | be.aux | ever | break.pfv.pst | break.ipfv.pst | leg | | |

| | | | ‘Have you ever broken a leg?’ | | |

| | | B: | Ne, | vlastně | jsem si | nikdy v životě | zlomil | *lomil | nohu | |

| | | | no | actually | be.aux | never in life | break.pfv.pst | break.ipfv.pst | leg | |

| | | | ‘No, I have never broken a leg.’ | |

| | b. | A: | Czy | kiedykolwiek | złamałeś | /*łamałeś | nogę? | | | POL |

| | | | Q | ever | break.pfv.pst | break.ipfv.pst | leg | | | |

| | | | ‘Have you ever broken a leg? | |

| | | B. | Nie, | nigdy | nie | złamałem | *łamałem | nogi. | | |

| | | | no | never | not | break.pfv.pst | break.ipfv.pst | leg | | |

| | | | ’No, I have never broken a leg in my life.’ | |

| | c. | A: | Ali | si si | že kdaj | zlomil | /*lomil | nogo? | | SLV |

| | | | Q | aux refl | ever | break.pfv.pst | | leg | | |

| | | ‘Have you ever broken a leg?’ | |

| | | B. | Ne, | nikoli v življenju | si še | nisem | zlomil | /*lomil | nogu. | |

| | | | | never in life | aux yet | neg-aux | break.pfv.pst | break.ipfv.pst | leg | |

| | | | ’No, I have never broken a leg in my life.’ | |

| | d. | A. | Da | li | si | ikada | slomio | /*lomio | nogu? | SRP |

| | | | Q | Q | aux | ever | break.pfv.pst | break.ipfv.pst | leg | |

| | | | ’Have you ever broken a leg?’ | |

| | | B. | nikada u životu | nisam | slomio | /*lomio | nogu. | | |

| | | | never in life | neg-aux | break.pfv.pst | break.ipfv.pst | leg | | |

| | | ’No, I have never broken a leg.’ | |

Similarly, in East Slavic languages, the perfective aspect is highly constrained in contexts with iterativity, inducing adverbials of definite cardinality, as shown in (34).

| (34) | a. | Marysja | ela | /*z’ela | cukerki | nekal’ki razoŭ | na minulym tydni | BEL |

| | | Mary | eat.ipfv.pst | eat.pfv.pst | candy | several times | last week | |

| | | ‘Mary ate a candy several times last week.’ | |

| | b. | Na prošloj nedele | Nataša | neskol’ko raz | ela | /*s’ela | konfety. | RUS |

| | | last week | Nataly | many times | eat.ipfv.pst | eat.pfv.pst | candy | |

| | | ‘Mary ate a candy several times last week.’ | |

| | c. | Mynuloho tyžnja | Marija | kil’ka raziv | jila | /*z’jila | cukerky. | UKR |

| | | Many times | Mary | several times | eat.ipfv.pst | eat.pfv.pst | candy | |

| | | ‘Mary ate a candy several times last week.’ | |

By contrast, West Slavic and Southwest Slavic languages use the perfective aspect in multiplicative contexts, as shown in (35).

| (35) | a. | Maria | snědla | /*jídla | minulý týden | několikrát | bonbón. | CZ |

| | | Maria | eat.pfv.pst | eat.ipfv.pst | last week | several times | candy | |

| | | Mary ate a candy several times last week.’ | |

| | b. | Marysia | zjadła | /?jadła | cukierka | kilka razy | w zeszłym tygodniu. | POL |

| | | Mary | eat.pfv.pst | eat.ipfv.pst | candy | several times | last week | |

| | | ‘Mary ate a candy several times last week.’ | |

| | c. | Marija je | prošle nedelje | nekoliko puta | pojela | /?jela | bombonu. | SRP |

| | | Mary aux | last week | several times | eat.pfv.pst | eat.ipfv.pst | candy | |

| | | ‘Mary ate a candy several times last week.’ | |

| | d. | Marija je | prejšnji teden | nekajkrat | pojela | /?jela | bonbon. | SLV |

| | | Mary aux | last week | many times | eat.pfv.pst | eat.ipfv.pst | candy | |

| | | ‘Mary ate a candy several times last week.’ | |

4.5. On the Inhibited Event Reading of Negated Perfective in East Slavic

When the neg operator acts over the event domain (¬vP), the only reading possible is the inhibited event reading, implying that there was a situation at a particular past interval in the actual world at which the event under consideration was expected to happen but failed to be realized or it was initiated but failed to be completed, which explains the confession effect in the court scenario arising in

neg + pfv past tense contexts in East Slavic. In order to account for the inhibited event reading, we resort to

Fábregas and González (

2020), who assume, following

Ramchand (

2004,

2008a,

2008b), that the event domain corresponds to the first phase of the derivation (the so-called first-phase syntax), which consists of three sub-events: an initiation sub-event (e1), a process sub-event (e2), and a sub-event corresponding to the resulting state (e3). Each of these sub-events is represented as its own projection, ordered hierarchically, and each of them has an event participant projected in the specifier position, as demonstrated in (36).

| (36) | ![Languages 10 00078 i003]() |

The initiation sub-event (e1) has the INITIATOR in the specifier position. The initiation sub-event e1 leads to the process sub-event e2 that is present in every dynamic verb. The process sub-event e2 corresponds to the VP projection, with the UNDERGOER in the specifier position. The process sub-event may optionally lead to the result phrase, corresponding to the result state of the event, with the RESULTEE (the holder of a ‘result state’) in the specifier position. In this chain of events, e1 causally implicates e2, and e2 causally implicates e3. Now, let us consider how the inhibited eventuality reading arises under low negation scoping over the event domain (vP). Negation either scopes over the initiation subevent. In this case, negation reverses the cause relation to an inhibition relation, producing the entailment that the agent planned the event but inhibited its realization. Alternatively, negation scopes over the process subevent. In this case, negation reverses the cause relation between the process subevent e2 and the result subevent e3 to an inhibition relation, producing the entailment that the agent initiated the event but inhibited the result subevent.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the intricate variation in the interaction of aspect and negation in past tense contexts across East and selected West and Southwest Slavic. We propose that negation in Slavic can merge at two different positions within the clause structure and at the Logical Form, with each position determining its scope over specific elements. The negated event reading arises when negation scopes above the TP, whereas the inhibited eventuality reading emerges when negation scopes over the vP (event domain). Our analysis demonstrates that East Slavic languages, unlike their West and Southwest counterparts, exhibit an inhibited event reading in negated perfective past tense contexts. This reading implies that the event was planned or initiated but ultimately unrealized, a pattern rooted in the interaction of the pfv aspect with negation and past tense. We propose that this phenomenon arises from the semantics of the pfv aspect in East Slavic, which parallels the interpretation of specific indefinites in the nominal domain. The aspectual head introduces a temporal variable t, restricted by a choice function to a singleton set, resulting in a presupposition of the existence of a specific temporal interval to which the event under consideration is anchored at the TP. This presupposition cannot be overridden by negation. Consequently, East Slavic blocks high negation, enforcing low negation over the event domain and giving rise to the inhibited event reading. By adopting a formal framework that distinguishes between high and low negation in Slavic, this study provides a unified account of the observed variation and sheds light on broader cross-linguistic patterns in the interaction of aspect, negation, and tense. These findings open new avenues for exploring the role of aspectual semantics in shaping syntactic and interpretative constraints in negative contexts across languages.