Variation in the Amplifier System Among Chinese L2 English Speakers in Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Amplifiers

| (1) | a. | I think that would be a very good try. (participant B6) |

| b. | So I think the market is- is a very important factor here. (participant B4) | |

| c. | It’s still very hard for me. (participant A5) | |

| d. | They’re all very delicious. (participant B7) | |

| (nouns underlined; amplifiers and adjectives bolded and italicized) |

2.2. Variation in the Amplifier System of Native English Speakers

2.3. English Amplifiers in Australia

2.4. Amplifier Variation Among L2 English Learners

2.5. The Collocation Patterns of Amplifiers Among L2 English Learners

- Do Chinese L2 English learners in Australia follow the distribution pattern of AusE in the use of English amplifiers?

- How do Chinese L2 English learners compare with AusE speakers in their collocation patterns of the amplifiers so, very and really, that are currently prevalent in English varieties?

- Do the factors of (self-reported) gender, length of residence in Australia, and language proficiency influence Chinese L2 English learners’ use of so, very, pretty, and really?

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Setting and Participants

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Australian English Data

3.5. Coding Process

| (2) | a. | I started as an international student here in Australia out in October 2017. (participant B1) |

| b. | I become more- I became more confident in academic writing. (participant A2) | |

| c. | Because it’s a compulsory subject so I have no choice. (participant B1) |

| (3) | a. | So (=conjunction) first one. (participant A3) |

| b. | It’s really (=truly) a subjective question. (participant B1) |

| (4) | a. | And it was- it was overall pleasant journey because- even if the weather was not so good. (participant B2) |

| b. | But that’s not really convenient. (participant B7) | |

| c. | It is not very convenient in Australia. (participant B6) |

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Overall Distribution of Amplifiers

4.2. Collocation Patterns of the Main Amplifiers

| (5) | a. | It was good- really, really good. (Participant A3) |

| b. | I mean, although professors and lecturers they’re very, very patient and very | |

| friendly to us. (Participant B2) | ||

| c. | No, actually they’re really, really tight and uncomfortable and rubbery. | |

| (AusE speaker 2–959) | ||

| d. | And as I was going up there, one of the very, very, very drunk English woman | |

| [sic]- turned around. (AusE speaker 3–794) |

4.3. Analysis of the Effect of Linguistic-External Constraints

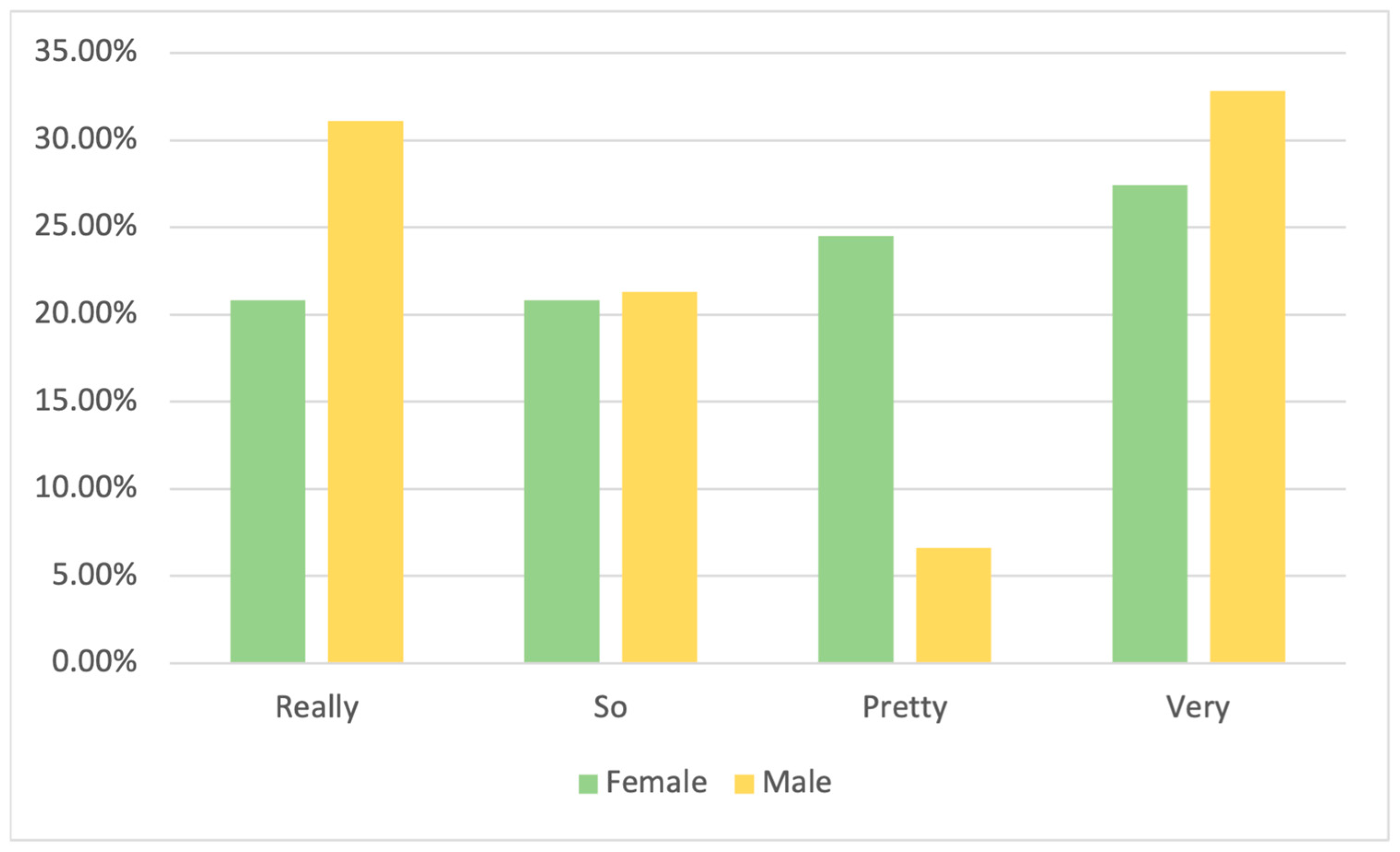

4.3.1. Comparison Between Gender Groups

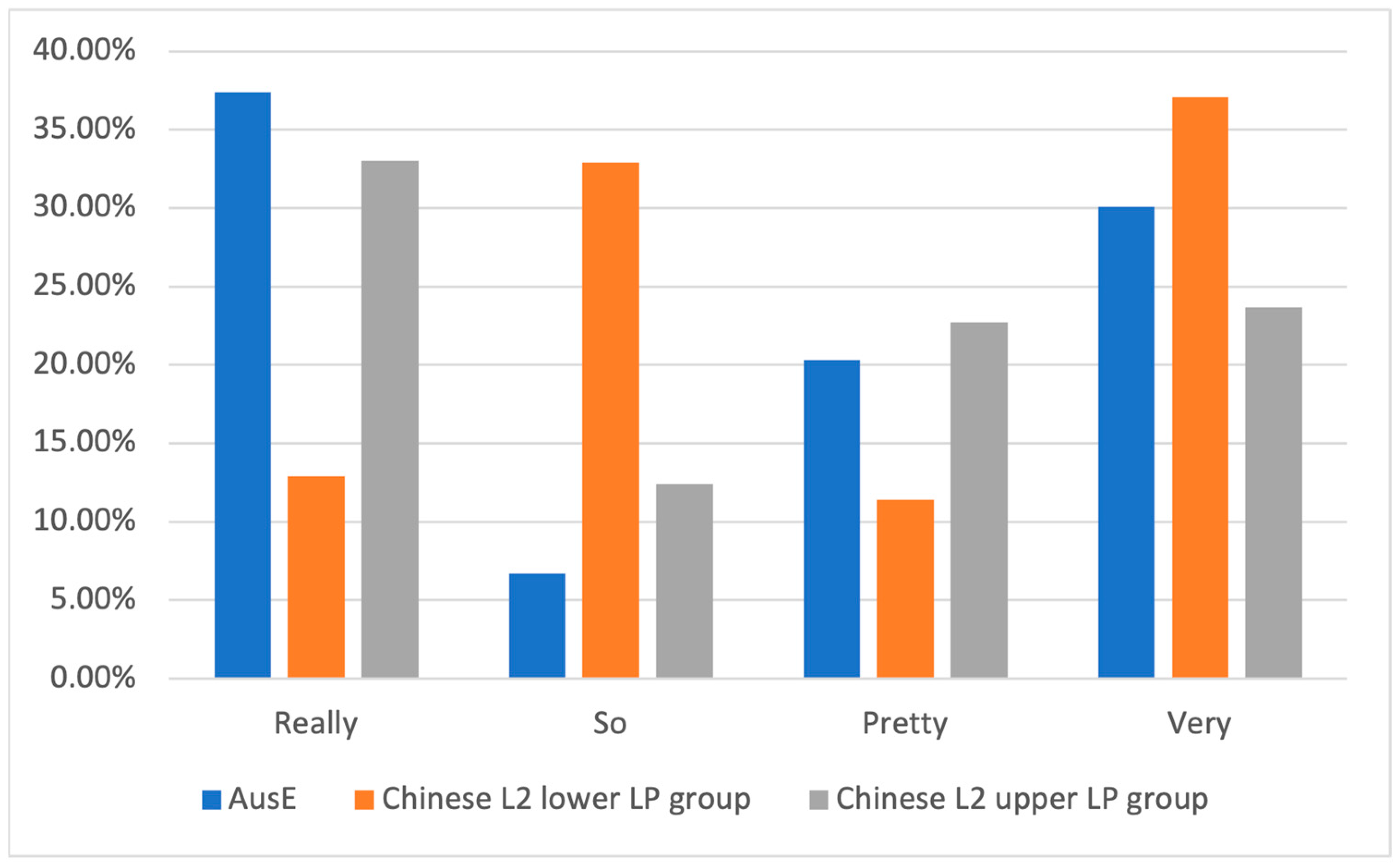

4.3.2. Comparison Between English Proficiency Groups

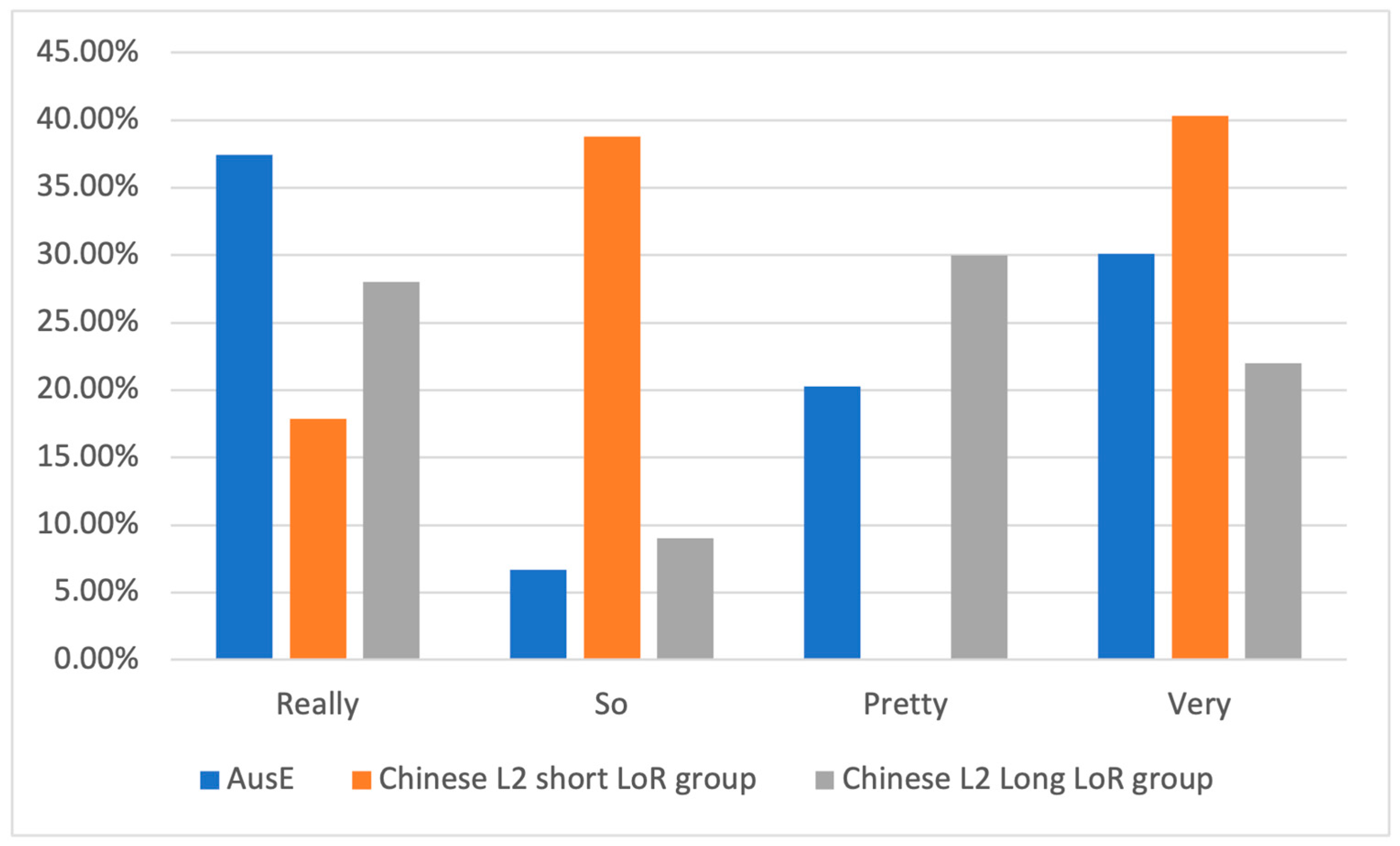

4.3.3. Comparison Between Length of Residence Groups

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Participant Code | Gender | IELTS/Equivalent Band (Score) | LP Group | Age | LoR (Months) | LoR Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Female | 6.5 | Lower | 23 | 18 | Long |

| A2 | Female | 6.5 | Lower | 24 | 1.5 | Short |

| A3 | Female | 6.5 | Lower | 24 | 9 | Short |

| A4 | Male | 6.5 | Lower | 24 | 15 | Long |

| A5 | Female | 6.5 | Lower | 26 | 15 | Long |

| B1 | Female | 7.5 | Upper | 24 | 66 | Long |

| B2 | Female | 7 | Upper | 24 | 15 | Long |

| B4 | Male | 7.5 | Upper | 23 | 15 | Long |

| B5 | Male | 7 | Upper | 23 | 31 | Long |

| B6 | Male | 7 | Upper | 24 | 6 | Short |

| B7 | Male | 7.5 | Upper | 23 | 9 | Short |

Appendix B

- Full Name:____________________

- Date of Birth: DD/MM/YYYY

- Gender:________

- What is/are your first language(s)?______________

- What is your highest English test score to date (e.g., IELTS, TOEFL, etc.)?______in___________

- At what age did you start learning English?___________

- Which university are you studying in?_________________________________-

- What is/are your major(s)?______________________________

- 9.

- How long have you studied in an Australian university (in months)?________

- 10.

- How long have you lived in Australia (in months)?_________

- 11.

- How many Australian friends do you have?

- 12.

- How many Australian acquaintances do you have?

- 13.

- How many Chinese friends do you have in Australia?

- 14.

- How many Chinese acquaintances do you have in Australia?

- 15.

- What language do you speak with your acquaintances and friends in Australia most of the time?

- 16.

- Do you read English language magazines, newspapers, or online publications? Please select one from the following three options

- Yes, frequently.

- Yes, occasionally.

- No

- 17.

- Do you prefer to watch TV and video clips in Chinese or English? Please select one from the following three options

- English

- Chinese

- Other_____________

- 18.

- Do you use English to deal with daily issues (shopping, renting an apartment, at restaurants, etc.)? Please select one from the following four options

- I use English all the time.

- I use English most of the time, but I occasionally speak Chinese in places like Asian groceries and Chinese restaurants.

- I use Chinese or _________ most of the time, I speak English only when_______________________________

- I only find people who speak Chinese to deal with those issues.

| 1 | Downtoners, including approximators (e.g., almost), compromisers (e.g., more and less), diminishers (e.g., partly) and minimizers (e.g., hardly), are all excluded in the current study. |

| 2 | The Boruta analysis is a variable selection procedure. It is employed to streamline the model fitting process of a mixed-model regression analysis in Schweinberger (2021). |

| 3 | Hong Kong English, Indian English, and Philippine English cannot be strictly classified into L2/non-native varieties. However, as “outer circle” varieties, they are distinct from inner circle English (e.g., British English, American English, and Australian English) (Kachru, 1985, p. 12). |

| 4 | Identifiable elements in the recording, including names of places (except cities and countries), university subjects, and people (e.g., teachers, classmates, and friends), were replaced with pseudonyms. |

| 5 | In this case, “fēi cháng fēi cháng + adjective” would be employed in a Chinese sentence. |

References

- Aijmer, K. (2018). That’s well bad: Some new intensifiers in spoken British English. In V. Brezina, R. Love, & K. Aijmer (Eds.), Corpus approaches to contemporary British speech (pp. 60–95). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Allerton, D. J. (1987). English intensifiers and their idiosyncrasies. In R. Steele, & T. Threadgold (Eds.), Language topics: Essays in honour of Michael Halliday (pp. 15–31). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K. (2013). The sociolinguistic interview. In C. Mallinson, B. Childs, & G. Van Herk (Eds.), Data collection in sociolinguistics: Methods and applications (pp. 91–100). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bolinger, D. (1972). Degree words. Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, D., Estival, D., Fazio, S., Viethen, J., Cox, F., Dale, R., Cassidy, S., Epps, J., Togneri, R., Wagner, M., Kinoshita, Y., Göcke, R., Arciuli, J., Onslow, M., Lewis, T., Butcher, A., & Hajek, J. (2011, August 27–31). Building an audio-visual corpus of Australian English: Large corpus collection with an economical portable and replicable black box. 12th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (Interspeech 2011), (P. Cosi, R. De Mori, G. Di Fabbrizio, & R. Pieraccini, Eds.; pp. 841–844). Florence, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, N. (2013). An Investigation of the adjectives in new Chinese words since the 1990s. Modern Chinese, 7, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 11–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. (2021). The use of the discourse-pragmatic markers like, well, actually and you know by Chinese students in Australia [Master’s thesis, University of Melbourne]. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. K., & Diskin-Holdaway, C. (2022). The Acquisition of Quotatives and Quotative Be Like among Chinese L2 Speakers of English in Australia. Languages, 7(2), 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, A. (2015). Stability, stasis and change—The longue durée of intensification. Diachronica, 32, 449–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, J. (2019). Quotation in indigenised and learner English: A sociolinguistic account of variation. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Davydova, J. (2023). Tracking global English changes through local data: Intensifiers in German learner English. International Journal of Bilingualism. (OnlineFirst). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Klerk, V. (2005). Expressing levels of intensity in Xhosa English. English World-Wide, 26, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diskin, C. (2015). Discourse-pragmatic variation and language ideologies among native and non-native speakers of English. A case study of Polish and Chinese migrants in Dublin, Ireland [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University College Dublin. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, R. L. (2012). Plenty too much Chinese food: Variation in adjective and intensifier choice in native and non-native speakers of English [Master’s thesis, Kansas State University]. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2097/13921 (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Edmonds, A., & Gudmestad, A. (2014). Your participation is greatly/highly appreciated: Amplifier collocations in L2 English. The Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue Canadienne des Langues Vivantes, 70, 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, R. (2017). Do women (still) use more intensifiers than men? Recent change in the sociolinguistics of intensifiers in British English. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 22, 345–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeslin, K. (Ed.). (2022). The Routledge handbook of sociolinguistics and second language acquisition. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, K., & Long, A. Y. (2014). Sociolinguistics and second language acquisition: Learning to use language in context. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikx, I., Van Goethem, K., & Wulff, S. (2019). Intensifying constructions in French speaking L2 learners of English and Dutch: Cross-linguistic influence and exposure effects. International Journal of Learner Corpus Research, 5, 63–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IELTS. (n.d.-a). IELTS Scoring in Detail. Available online: https://ielts.org/take-a-test/your-results/ielts-scoring-in-detail (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- IELTS. (n.d.-b). IELTS and the CEFR. Available online: https://ielts.org/organisations/ielts-for-organisations/compare-ielts/ielts-and-the-cefr (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Ito, R., & Tagliamonte, S. A. (2003). Well weird, right dodgy, very strange, really cool: Layering and recycling in English intensifiers. Language in Society, 32, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, K. (1996). Teaching sociolinguistic knowledge in Japanese high schools. JALT Journal, 18, 327–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, B. B. (1985). Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the outer circle. In R. Quirk, & H. G. Widdowson (Eds.), English in the World: Teaching and learning the language and literatures (pp. 11–30). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwit, M. (2022). Sociolinguistic competence: What we know so far and where we’re heading. In K. Geeslin (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of sociolinguistics and second language acquisition (pp. 30–44). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic patterns. University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, W. (1984). Field methods of the project on linguistic change and variation. In J. Baugh, & J. Sherzer (Eds.), Language in use: Readings in sociolinguistics (pp. 28–53). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M. (2004). A Corpus-based study of intensifiers in Chinese EFL learners’ oral production. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 14, 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mede, E., & Dililitaş, K. (2015). Teaching and learning sociolinguistic competence: Teachers’ critical perceptions. Participatory Educational Research, 2, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Naya, B. (2017). Co-occurrence and iteration of intensifiers in Early English. English Text Construction, 10(2), 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merx, M. (2018). Very jolly and really wild: Development in Victoria English intensifiers. Working Papers of the Linguistic Circle of the University of Victoria, 28, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Meunier, F. (2012). Formulaic language and language teaching. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 32, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W. (2003). An outline of Chinese-English contrastive study. Beijing Language and Culture University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J. (2006). A corpus-based study of amplifiers among Chinese English learners. Journal of Xi’an International Studies University, 14, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G., & Svartvik, J. (1985). A comprehensive grammar of the English language. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Schleef, E., Meyerhoff, M., & Clark, L. (2011). Teenagers’ acquisition of variation: A comparison of locally-born and migrant teens’ realisation of English (ing) in Edinburgh and London. English World-Wide, 32, 206–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweinberger, M. (2020). How learner corpus research can inform language learning and teaching: An analysis of adjective amplification among L1 and L2 English speakers. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 43, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweinberger, M. (2021). Ongoing change in the Australian English amplifier system. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 41, 166–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweinberger, M. (2024). A corpus-based analysis of adjective amplification in Hong Kong, Indian and Philippine English. World Englishes, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y. (2016). Corpus-based comparative study of intensifiers: Quite, pretty, rather and fairly. Journal of World Languages, 3, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, S. A. (2006). Analysing sociolinguistic variation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, S. A. (2008). So different and pretty cool! Recycling intensifiers in Toronto, Canada. English Language & Linguistics, 12, 361–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, S. A. (2016). Teen talk. The language of adolescents. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, S. A., & Denis, D. (2014). Expanding the transmission/diffusion dichotomy: Evidence from Canada. Language, 90, 90–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y. (2023). Chinese international students to move from Zoom to Room: Implications for Australia. Australian Outlook. Available online: https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/chinese-international-students-to-move-from-zoom-to-room-implications-for-australia/ (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Xiao, R., & Tao, H. (2007). A corpus-based sociolinguistic study of amplifiers in British English. Sociolinguistic Studies, 1, 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-F. (2022). A study on the reduplication of degree adverbs. Chinese Language Learning, 4, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

| English Variety | Amplifier Variants |

|---|---|

| AusE (Schweinberger, 2021) | Really, very, so, pretty, bloody, absolutely, totally, completely, extremely, particularly, true, actually, awfully, genuinely, incredibly, real, strongly |

| Amplified | 0 Amplification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese L2 | 50.2% | N = 167 | 49.8% | N = 166 |

| AusE | 34.8% | N = 163 | 65.2% | N = 306 |

| Variant | Chinese L2 % | Chinese L2 N | AusE % | AusE N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very | 29.3% | 49 | 30.1% | 49 |

| Really | 24.6% | 41 | 37.4% | 61 |

| So | 20.9% | 35 | 6.7% | 11 |

| Pretty | 18% | 30 | 20.3% | 33 |

| Bloody | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Too | 3.6% | 6 | 0.6% | 1 |

| Totally | 1.2% | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Especially | 0.6% | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Super | 0.6% | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Extremely | 0.6% | 1 | 0.6% | 1 |

| Perfectly | 0.6% | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Completely | 0 | 0 | 2.5% | 4 |

| Absolutely | 0 | 0 | 1.8% | 3 |

| Total | 167 | 163 |

| Variant | Chinese L2 % | Chinese L2 N | AusE % | AusE N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicative | Really | 22.2% | 28 | 35.1% | 45 |

| Very | 21.4% | 27 | 29.7% | 38 | |

| So | 27.8% | 35 | 8.6% | 11 | |

| Pretty | 20.7% | 26 | 21.1% | 27 | |

| Other | 7.9% | 10 | 5.5% | 7 | |

| Total | 126 | 128 | |||

| Attributive | Really | 31.7% | 13 | 45.7% | 16 |

| Very | 53.6% | 22 | 31.4% | 11 | |

| So | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pretty | 9.8% | 4 | 17.2% | 6 | |

| Other | 4.9% | 2 | 5.7% | 2 | |

| Total | 41 | 35 |

| Variant | Group | Adjective Types N | Variant Frequency N | LD Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Really | Chinese L2 | 28 | 41 | 0.68 |

| AusE | 37 | 61 | 0.61 | |

| Very | Chinese L2 | 33 | 49 | 0.67 |

| AusE | 38 | 49 | 0.78 | |

| So | Chinese L2 | 29 | 35 | 0.83 |

| AusE | 10 | 11 | 0.91 |

| Chinese L2 | AusE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Really | Good | 19.5% | Good | 27.9% |

| Different, depressed * | 7.3% | Nice, great | 4.9% | |

| Hard, interesting | 4.9% | Bad, beautiful, fun, hollow, lovely | 3.3% | |

| Very | Good | 14.3% | Nice | 10.2% |

| Different | 8.2% | Good | 8.2% | |

| Delicious, simple | 6.1% | Cute, old | 6.1% | |

| Amplified | 0 Amplification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 53.8% | N = 106 | 46.2% | N = 91 |

| Male | 44.9% | N = 61 | 55.1% | N = 75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miao, M.; Diskin-Holdaway, C. Variation in the Amplifier System Among Chinese L2 English Speakers in Australia. Languages 2025, 10, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040069

Miao M, Diskin-Holdaway C. Variation in the Amplifier System Among Chinese L2 English Speakers in Australia. Languages. 2025; 10(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiao, Minghao, and Chloé Diskin-Holdaway. 2025. "Variation in the Amplifier System Among Chinese L2 English Speakers in Australia" Languages 10, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040069

APA StyleMiao, M., & Diskin-Holdaway, C. (2025). Variation in the Amplifier System Among Chinese L2 English Speakers in Australia. Languages, 10(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040069