1. Introduction

Scholars have recognized the unity of the Bantu language family since the nineteenth century CE (

Bostoen & Van de Velde, 2019, p. 6). In recent decades, our understanding of Bantu subclassification has been refined thanks to Bantu-wide lexicon-based quantitative approaches, first lexicostatistics (

Bastin et al., 1999) and later Bayesian phylogenetics (

Grollemund et al., 2015;

Koile et al., 2022). These internal classifications relying on basic vocabulary have solidified the consensus that the highest diversity within Bantu lies in the northwest. The languages in the large eastern and southern parts of the Bantu-speaking area are numerous and spoken by the vast majority of Bantu speakers, but they form a relatively late and homogenous branch (

Grollemund et al., 2015;

Koile et al., 2022), reminiscent of what is called ‘Savanna Bantu’ in earlier literature (

Ehret, 1999,

2001). Although

Grollemund et al. (

2015) further subdivide this clade into Southwestern and Eastern Bantu, this subdivision does not match with discrete monophyletic groups in the ‘ladderized’ or onion-like topology of their tree, i.e., clades successively splitting off from the central backbone (

Pacchiarotti & Bostoen, 2020, p. 163). In

Koile et al. (

2022), who use the same lexical dataset and cognacy judgements as

Grollemund et al. (

2015) but different parameters in their phylogenetic model, Southwestern and Eastern Bantu do emerge as two well-supported discrete monophyletic groups, which form sister clades more closely related to each other than to the remainder of Bantu.

Despite recent advances, some areas of Bantu subclassification remain hazy, and some individual Bantu languages continue to defy classification. In this study, we focus on such a classificatory rebel, namely Yeyi (R41), a Bantu language of Botswana and Namibia. On the one hand, the Bantu affiliation of Yeyi is undeniable. It has a large number of lexemes of clear Bantu origin with cognates in Bantu languages nearby and further away (

Gowlett, 1992,

1997). Beyond lexicon, it also has, for instance, a full system of noun classes marked through prefixes on nouns and agreement prefixes on dependents, which is unmistakably inherited from Proto-Bantu (

Seidel, 2008, pp. 101–129). The same holds for several other domains of Yeyi grammar. On the other hand, Yeyi’s genealogy within Bantu is still unclear. None of its Bantu neighbors are similar enough to be considered a close relative. It is even not clear to which major Bantu subclade Yeyi belongs, as it features in none of the lexicon-based Bantu-wide genealogical classifications, except for the lexicostatistical study of

Heine et al. (

1977).

In this paper, we resolve some of the uncertainties surrounding Yeyi’s classification and history through a new linguistic phylogeny explicitly focused on elucidating Yeyi’s genealogy. In

Section 2, we introduce the Yeyi language, its modern and historical sociolinguistic setting, especially with regard to contact with other Bantu languages and non-Bantu languages, and earlier attempts at or suggestions about Yeyi classification. In

Section 3, we introduce our dataset and methodology. In

Section 4, we present the resultant phylogenetic classification, while we interpret these results in terms of the population history of Yeyi speakers in

Section 5. In

Section 6, we summarize our conclusions.

2. Previous Approaches to Yeyi Classification

Yeyi is spoken in northwestern Botswana and northeastern Namibia. In Namibia, the Yeyi speech community is concentrated in the southern part of the Zambezi region (formerly known as the East Caprivi). In Botswana, Yeyi speakers are mostly found in the Northwest or Ngamiland district, living in and around the Okavango delta. The Yeyi people consider their Namibian habitat to be their original homeland, with the expansion into Botswana dated to around 1650 (

Westphal, 1964;

Tlou, 1985;

Larson, 1989).

In both Botswana and Namibia, Yeyi is spoken in a highly multilingual setting. In Namibia, Yeyi is in contact with Fwe (K402), Totela (K41), and Subiya (K42), all members of the western branch of the closely related and relatively well-studied Bantu Botatwe (

Bostoen, 2009;

de Luna, 2010), which forms a discrete subgroup within Eastern Bantu in both

Grollemund et al. (

2015) and

Koile et al. (

2022), though with only three eastern members represented, i.e., Lenje (M61), Soli (M62), and Tonga (M64). Lozi (K21) is the regional lingua franca, a Bantu language that developed when Southern Sotho speakers from South Africa fled to Western Zambia in the mid-nineteenth century CE, where they came into contact with speakers of Luyi (K31). The resultant Lozi language combines a distinctly Luyi-influenced phonology with a basic lexicon and grammatical system that betrays its Sotho origin (

Gowlett, 1989). Mbukushu (K333), which is in contact with Yeyi in both Botswana and Namibia, is spoken across southern Angola, northern Namibia, western Zambia, and northwestern Botswana, and is part of the Luyana cluster of languages spoken across large parts of Western Zambia (

Lisimba, 1982). Another Bantu language that borders on Yeyi in Botswana is Tswana (S31), the national language of Botswana, especially its Tawana variety. Tswana’s dominance in Botswana is triggering language shift (

Sommer, 1995), and, much more than Namibian Yeyi, Botswana Yeyi counts as endangered, in spite of recent and ongoing grassroots revitalization attempts (

Nyati-Ramahobo, 2002;

Nyati-Saleshando, 2019).

In addition to Bantu speakers, Yeyi speakers are also in contact with speakers of various Khoisan languages, particularly Khwe, a language of the Khoe–Kwadi family, and Ju, a language of the Kx’a family. This has led to heavy Khoisan influence on Yeyi, which is seen in its lexicon (

Sommer & Voßen, 1992;

Gunnink et al., 2015), verbal morphology (

Gunnink, 2022), but most clearly in its extensive use of clicks. Clicks are cross-linguistically very rare phonemes that are ubiquitous in Khoisan languages, but are also found in some languages spoken relatively close to Khoisan, such as Bantu languages of southern Africa. This makes the use of clicks in Bantu languages a clearly recognizable sign of Khoisan interference (

Vossen, 1997;

Sands & Güldemann, 2009;

Pakendorf et al., 2017). Click inventories in Yeyi differ between Botswana Yeyi and Namibian Yeyi, and especially in Botswana Yeyi, they seem to be subject to a great degree of regional and idiolectal variation (

Sommer, 2017), possibly linked to the ongoing process of language loss (

Sommer & Vossen, 1995). Botswana Yeyi distinguishes up to 22 different clicks, including four click types, dental, alveolar, lateral, and palatal (

Sommer & Voßen, 1992;

Fulop et al., 2003), making Botswana Yeyi the only living Bantu language to have phonemic palatal clicks (

Pakendorf et al., 2017). The Namibian Yeyi click inventory is smaller, does not make use of palatal clicks, and uses lateral clicks only marginally (

Donnelly, 1991, pp. 13–15;

Seidel, 2008, pp. 40–43).

The extensive Khoisan influence on Yeyi may be one of the reasons why Yeyi is hard to classify within Bantu, especially if this contact-induced influence has replaced inherited Bantu material that would have been able to shed light on Yeyi’s closest Bantu relatives. The unclear genealogical affinities of Yeyi have led to wildly different proposals. Andersson, a Swedish traveler who visited the Okavango delta in the mid-nineteenth century CE and collected some of the earliest written Yeyi data, considered Yeyi to share similarities with Herero (R31), a Bantu language spoken in Namibia (

Andersson, 1855, pp. 19–20). However, this suggestion was probably prompted by Andersson’s longer experience with Herero compared to other Bantu languages. A similar western orientation for Yeyi was implicitly suggested by

Guthrie (

1948), who classified Yeyi into zone R together with Umbundu (R10), Wambo (R20), and Herero (R30), all spoken in Angola and Namibia, but as a separate subgroup (R40), therefore emphasizing its relatively isolated status.

Johnston (

1919), on the other hand, links Yeyi to the Luyana (K30) cluster spoken in western Zambia. These languages all form part of Southwestern Bantu (

Grollemund et al., 2015;

Koile et al., 2022).

Other attempts at Yeyi classification have rather suggested its inclusion in Eastern Bantu.

Heine et al. (

1977), for example, include Yeyi in their “Osthochland-Gruppe”, which roughly corresponds to Eastern Bantu in recent phylogenies (

Grollemund et al., 2015;

Koile et al., 2022). It has also been suggested that Yeyi may be affiliated with the Bantu Botatwe subgroup, although these suggestions do not seem to be based on much more than geographical contiguity (

Tlou, 1985;

Gowlett, 1997).

Seidel (

2005) compares Yeyi to other languages spoken in the (then) Caprivi strip of Namibia. Although this limited geographic focus prevents the identification of Yeyi relatives spoken further away, it is one of the few attempts at Yeyi classification that employs a clear methodology, comparing Yeyi to surrounding languages in terms of phonology and basic lexicon. Layered language genesis, consisting of different strata of influence from various Khoisan as well as Bantu languages, would then account for the unique profile of Yeyi (

Seidel, 2009).

In sum, previous proposals of Yeyi classification have pointed in very different directions, but mostly miss a consistent methodology, or use only a relatively small sample of languages to compare Yeyi to. Bantu-wide lexicon-based classifications since 1999 have unfortunately not included Yeyi, which means that the possibility of Yeyi sharing a closer genealogical relationship with languages now spoken further away has not yet been investigated.

3. Data and Methodology

In order to clarify the genealogical position of Yeyi with respect to other Bantu languages, we provide a new, lexicon-based, Bayesian phylogenetic classification. We collected linguistic data for nine Yeyi doculects, i.e., varieties documented by different authors in different times and places. These consist of five sources on Botswana Yeyi (

Livingstone, 1851;

Andersson, 1855;

Schapera & van der Merwe, 1942;

Sommer, 1995;

Lukusa, 2009) and four on Namibian Yeyi (

Donnelly, 1991;

Gowlett, 1992;

Seidel, 2005,

2008), spanning a period of some 150 years.

Some of these sources represent Yeyi varieties that are similar enough to each other to be considered the same language. We therefore created two datasets, one where all Yeyi doculects were kept separately and one where Yeyi doculects collected in similar areas during a similar period were merged. In this latter dataset, we merged the Namibian data published in

Donnelly (

1991) with those published in

Seidel (

2005,

2008), and we merged the Botswana Yeyi data published in

Schapera and van der Merwe (

1942) with those published in

Sommer (

1995). Although

Andersson (

1855) and

Livingstone (

1851) were working in the area of modern-day Botswana, we kept their nineteenth-century CE data separate given their age and the lack of details on the exact location of data collection. As

Gowlett (

1992,

1997) occasionally combines Yeyi data from Namibia and Botswana, we removed this source from the second dataset.

Lukusa (

2009) is not entirely clear on where the data were collected, although the use of palatal and lateral click phonemes in this source suggests that it represents the Botswana variety. These types of clicks occur in Yeyi of Botswana, but not that of Namibia. Given the homogenous nature of the data, we included this source in the second dataset, albeit without a definitive classification as either Botswana or Namibia.

Our non-Yeyi dataset was created to test the different affiliations for Yeyi that have been proposed in the literature, combined with languages spoken in the wider geographic area where Yeyi is spoken today. Given earlier suggestions that Yeyi might be of Eastern Bantu origin, we also included 38 Bantu languages of wider Eastern Bantu affiliation, despite being spoken far away from Yeyi. Finally, we added languages from the known subgroups of Bantu according to

Grollemund et al. (

2015), e.g., North-Western, Central-Western, West-Western (also called West-Coastal in

Pacchiarotti et al., 2019, among others), and we rooted the tree with Duala (A24), a North-Western Bantu language. The complete list of languages used in our classification can be found in the

Supplementary Materials.

For each of the languages in our dataset, we collected words for a list of 100 basic concepts. We focused on basic lexicon because it is more resistant to contact-induced change, and, therefore less likely to include borrowings which may obscure Yeyi’s genealogical origins. This list is loosely based on the 92-word list used by

Bastin et al. (

1999) and the 100-word list used by

Grollemund et al. (

2015), but has been adapted in several ways.

Firstly, words that, at least in our dataset, appear to be prone to recurrent sound-symbolic associations were removed. For instance, the concept ‘round’ is frequently expressed by words containing rounded vowels and/or bilabial consonants. The occurrence of similar phonetic shapes for words with this meaning, therefore, could be either a sign of shared inheritance or of similar form-meaning associations which arose independently in different languages. Words which, during our initial data collection phases, appeared to be particularly prone to these kinds of sound-symbolic associations were therefore excluded from our word list.

Secondly, a number of concepts appeared, at least in our dataset, to be more prone to borrowing than expected. For instance, ‘to swim’, while found to be relatively borrowing-resistant cross-linguistically (

Haspelmath & Tadmor, 2009), frequently occurs in the Bantu languages in our dataset with phonemes which are described as only occurring in loanwords in the languages in question.

These problematic concepts were therefore replaced by concepts which, at least in the area under study, tend to be basic, such as ‘elephant’, ‘snake’, and ‘house’.

The forms for each concept were sorted into cognate sets, using as much as possible available analyses on the sound changes that the languages in question have undergone, but using more intuitive judgments where necessary. Subsequently, each cognate set was recoded as a binary character tracking the presence or absence of each particular root-concept association.

Our lexical data, along with cognate judgements, are available in the

Supplementary Materials. We constructed two lexical datasets, one keeping all Yeyi doculects separate (YeyiFull) and one with some Yeyi doculects merged, as explained above (YeyiMerged). We used lexedata v. 1.0.8 (

Kaiping et al., 2022) to facilitate editing and annotation of the lexical datasets, as well as for the conversion of cognate sets into coded matrices. We analyzed the resulting binary matrices with MrBayes 3.2.7a (

Ronquist et al., 2012). We used a simple binary model (also known as restriction site model), and default priors. All analyses were run for 20 million generations, and convergence was assessed with Tracer v.1.7.1 (

Rambaut et al., 2018) and the standard deviation of split frequencies, which fell below 0.01 in all cases. We tested for the addition of gamma-distributed rate variation across characters using Bayes Factors. We estimated the marginal probabilities with and without rate variation using the steppingstone method, as implemented in MrBayes 3.2.7a. All analyses were performed using the resources of CIPRES Science Gateway (

Miller et al., 2010).

4. Results

Our preliminary analyses with the full, unmerged dataset (YeyiFull) showed that all doculects of Yeyi form a highly supported clade and are very closely related (see file YeyiFull.pdf in online

Supplementary Material). The results of the merged dataset (YeyiMerged) were essentially identical, and we proceeded to use this dataset for the rest of the analyses. The comparison with Bayes Factors indicated decisive support for the inclusion of gamma rate heterogeneity (the estimated natural log of the marginal likelihood with gamma rate heterogeneity was −17,939.35, while the corresponding value without gamma rate heterogeneity was −18,315.92, giving a lnBF of 376.57) (

Kass & Raftery, 1995).

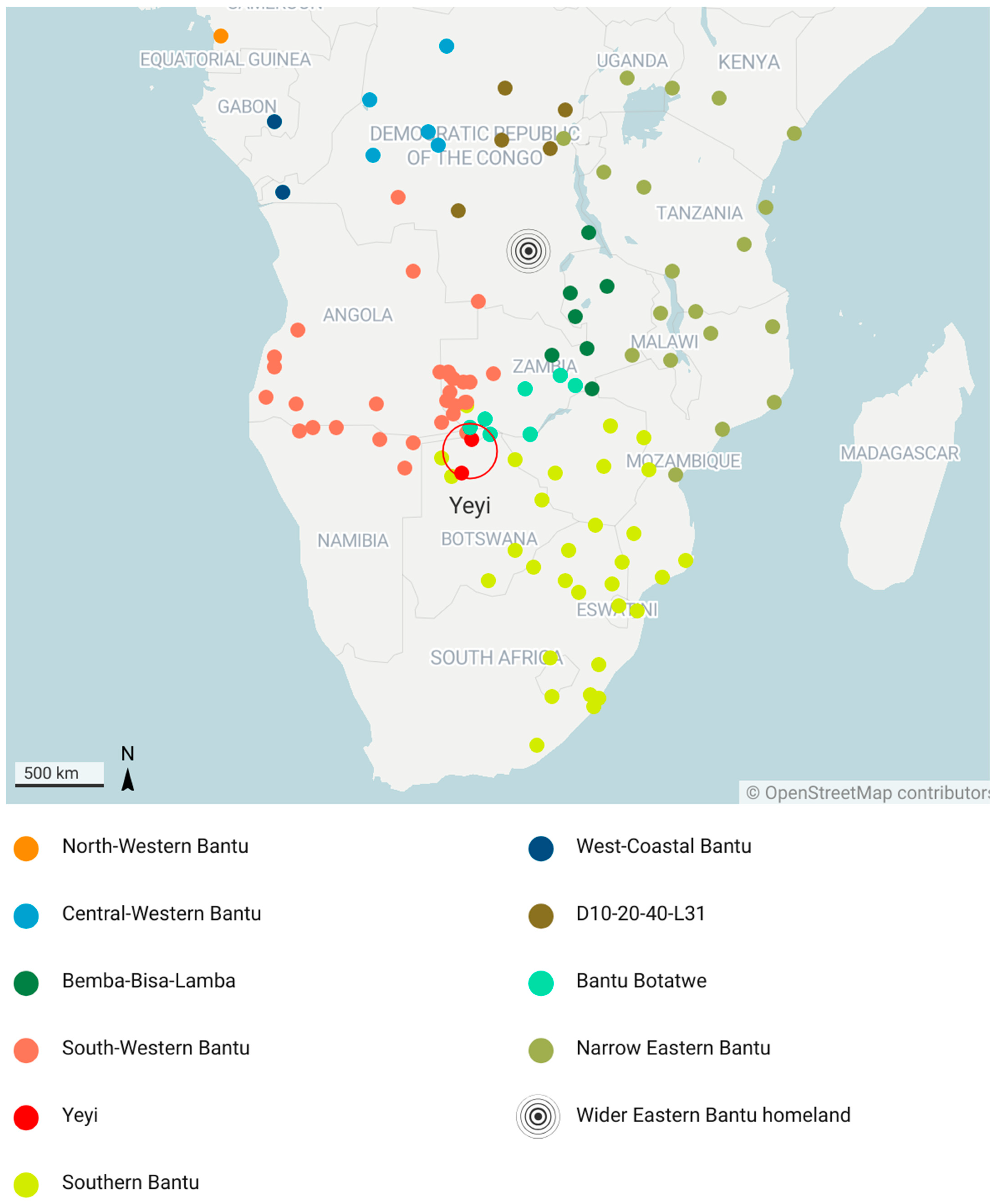

Figure 1 represents the linguistic phylogeny and the position of Yeyi.

Our phylogeny is rooted with Duala (A24), a North-Western Bantu language that is part of the primary clade in earlier Bantu phylogenies (

Grollemund et al., 2015;

Koile et al., 2022). Sister to Duala are one branch comprising the seven languages in our sample representative of two sub-branches in earlier phylogenies, i.e., West–Coastal/West–Western and Central–Western (

Grollemund et al., 2015;

Pacchiarotti et al., 2019;

Koile et al., 2022), and another branch including the remainder of our sample. As it contains languages spoken outside of the Congo Forest, we call this third primary clade in our phylogeny “Savanna Bantu”, a label used in earlier historical Bantu studies (cf.

Section 1), though not necessarily covering exactly the same languages. Our Savanna Bantu corresponds to the superclade including Southwestern and Eastern Bantu languages in previous Bantu phylogenies (

Grollemund et al., 2015;

Koile et al., 2022), which do not use this label. However, its internal topology in our results is different from theirs, especially with regard to the position of zone D languages of the eastern DRC and Luba (L31a) of the south–central DRC, which are the first two branches to split off in our classification, but have a more embedded position in previous Bantu phylogenies (

Grollemund et al., 2015;

Koile et al., 2022). This is probably due to the very incomplete representation of their closest relatives in our sample.

After the split off of zone D languages and Luba (L31a), the remainder of Savanna Bantu is a large clade splitting in two major subclades, which we label “Southwestern Bantu” and “Wider Eastern Bantu”. The languages included in our Southwestern Bantu correspond largely to Southwestern Bantu in previous phylogenies (

Grollemund et al., 2015;

Koile et al., 2022), except for Luba (L31a), as discussed above. “Wider Eastern Bantu” comprises a first clade uniting two subclades, i.e., “Bantu Botatwe” and “Bemba–Bisa–Lamba”. Bantu Botatwe in southwestern Zambia has already been recognized as a distinct subgroup on the basis of both lexicon and diachronic phonology (

Bostoen, 2009;

de Luna, 2010). The Bemba–Bisa–Lamba subclade unites languages from northeastern Zambia belonging to Guthrie’s referential M40 (Bemba) and M50 (Bisa-Lamba) groups. The second major clade within Wider Eastern Bantu comprises a subclade uniting all Yeyi doculects in our sample and a sister one which we call “Narrow Eastern Bantu” and clusters the remainder of Bantu languages spoken in eastern and southern Africa in our sample. All of these have also previously been classified as part of Eastern Bantu (

Grollemund et al., 2015;

Koile et al., 2022). Our Narrow Eastern Bantu also includes the Southern Bantu languages of southeastern Africa, which, as in previous phylogenies, are a low-level subgroup of Eastern Bantu (

Gunnink et al., 2023).

All Yeyi doculects in our study cluster closely together in a well-supported clade. As for its internal classification, this Yeyi clade does not show a clear split between Yeyi doculects of Botswana and Namibia. Namibian Yeyi appears most closely related to the variety of Yeyi documented by

Lukusa (

2009), which is not explicit about the origin of the data. The differentiation between Yeyi as spoken in Botswana and Namibia may, therefore, be seen in other domains of the language than the lexicon. As for its external classification, our phylogeny offers clear support for the classification of Yeyi as part of Wider Eastern Bantu. Lexical innovations that define Wider Eastern Bantu, and are also shared with Yeyi, include the root *dòpà ‘blood’ (BLR 1144) (

Bastin et al., 2002) and the

ini root for ‘liver’ that has reflexes in many Wider Eastern Bantu languages, e.g.,

li-ini in Manda (N11),

li-ini in Lenje (M61),

ɪk-ɪnye in Nyakyusa (M31),

ini in Swahili (G42), and

ini in Kikuyu (E51) (cf.

Nurse & Hinnebusch, 1993;

Samson & Schadeberg, 1994/1995). A cognate form

l-ine or

l-inye is also attested in Yeyi.

Yeyi’s closest relatives within Wider Eastern Bantu are the entirety of the languages which cluster as Narrow Eastern Bantu, and not the languages spoken in its immediate vicinity. The clade we label Southwestern Bantu, with languages spoken to the west and north of Yeyi, is well-supported in our phylogeny and excludes Yeyi. For example, lexical innovations defining Southwestern Bantu include *cʊdɪ ‘liver’ (BLR 4655), which has reflexes throughout Southwestern Bantu but not in Yeyi, or the loss of the reflex of *jínò ‘tooth’ (BLR 3472), which is maintained in Yeyi but lost throughout Southwestern Bantu.

Evidence for the inclusion of Yeyi in Bantu Botatwe is also not found. Bantu Botatwe languages cluster together as a well-supported clade, which belongs to a distinct Wider Eastern Bantu branch, and thus excludes Yeyi. One of the characteristic lexical innovations of Bantu Botatwe is the replacement of the inherited reflex of the root *tɪ́ ‘tree’ (BLR 2881) with a new root exclusively found in Bantu Botatwe, tentatively reconstructable as *camu on the basis of its reflexes such as

ci-ʃamu in Fwe and

ci-samu in Lenje (see also

de Luna, 2008,

2010). Yeyi, however, does not share in this innovation, but has retained

mu-ti ‘tree’ as a reflex of *tɪ́. Furthermore, there are sound changes that set Yeyi apart from Bantu Botatwe, such as the loss of nasals before voiceless consonants, which has affected Yeyi (

Gowlett, 1997) but not Bantu Botatwe (

Bostoen, 2009).

In other words, within Wider Eastern Bantu, Yeyi appears to be somewhat of a loner, having diverged from other Eastern Bantu languages relatively early. This is supported by the many lexical innovations in its basic vocabulary that Yeyi does not share with any other Bantu language, such as

in-goro ‘arm’,

li-dzundzo ‘cloud’,

hweta ‘speak’,

shi-poro ‘mouth’,

mashira ‘be sick’,

mu-nyana ‘man’, and

ma-shuta/ma-shita ‘milk’. These words are also not recognizable as Khoisan loanwords (although some Khoisan loans did enter Yeyi’s basic vocabulary, see

Table 1 below). The loner status of Yeyi is also reflected in its geographical isolation from its closest Narrow Eastern Bantu relatives, except for Tswana and Lozi (see

Figure 2). However, Southern Bantu, to which Tswana and Lozi belong, probably emerged in southern Africa not earlier than about a millennium ago (

Gunnink et al., 2023). The presence of Tswana in the Okavango delta, more specifically its Tawana variety, is even much more recent, i.e., the early nineteenth century CE (

Tlou, 1985). Similarly, the Lozi language only emerged after the migration of Sotho-speaking groups to western Zambia in the nineteenth century CE (

Gowlett, 1989) and is therefore also a relative newcomer. Furthermore, Yeyi is not part of the Southern Bantu subgroup, and its position within southern Africa can therefore not be taken to be part of the same northward expansion that brought Tswana and Lozi into the Botswana/Namibia/Zambia border region.

However, there is a theoretical possibility that ongoing contact with both Tswana and Lozi may have influenced the apparent Narrow Eastern Bantu affiliation of Yeyi. If Yeyi had borrowed extensively from Lozi and Tswana, and these similarities would be coded as cognates in our dataset, this could have created the false impression that Yeyi has inherited substantial Narrow Eastern Bantu material. However, while the Tswana and Lozi influence on Yeyi is undeniable (

Seidel, 2009), it is not identifiable in Yeyi’s basic vocabulary. Yeyi shares 48 cognates with either Lozi or Tswana, but almost all of these have a corresponding Proto-Bantu reconstruction and are more widely distributed than Narrow Eastern Bantu. Furthermore, there are marked phonological differences between these cognates in Yeyi and in Tswana and Lozi, which result from the very different historical phonological development of these languages. For instance, Tswana, Lozi and the other languages of the Sotho-Tswana cluster (S30) have not undergone Bantu Spirantization (

Creissels, 1999,

2007), the change of stops to fricatives under the influence of a reconstructed high vowel (

Schadeberg, 1994/1995;

Janson, 2007;

Bostoen, 2008). This widespread sound change did affect Yeyi (

Gowlett, 1992). The effects of Bantu Spirantization clearly show that, even when Yeyi forms are historically cognate with forms attested in Lozi and Tswana, Yeyi did not borrow these forms from Tswana or Lozi, in which case no spirantization would be attested. Rather, Yeyi forms consistently show spirantization, which indicates that they are inherited forms rather than borrowings, e.g., *jé

dì ‘moonlight’ (BLR 3283) (

Bastin et al., 2002) > Yeyi

ukw-ezi ‘moon’ vs. Lozi

kweli ‘moon’, Tswana

kgwedi ‘moon’.

Another remarkable sound change is the palatalization of bilabial consonants when followed by a rounded vowel, which has affected the Sotho languages Lozi and Tswana (

Kotzé & Zerbian, 2008), but not Yeyi, e.g., *

bʊ́à ‘dog’ (BLR 282) (

Bastin et al., 2002) > Yeyi

om-bwa ‘dog’ vs. Tswana

n-tʃa ‘dog’, Lozi

n-ja ‘dog; *

bʊ̀è ‘stone’ (BLR 285) (

Bastin et al., 2002) > Yeyi

li-we ‘stone’ vs. Lozi

li-cwe ‘stone’.

The phonological differences between Yeyi forms and their cognates in Lozi and Tswana therefore clearly show that Lozi or Tswana influence has not impacted Yeyi’s basic vocabulary, and therefore the analysis of the Yeyi cluster as a sister branch to Narrow Easter Bantu is unlikely to be an artefact of extensive contact-induced change.

Another possibility is that extensive contact-induced changes from Khoisan languages would have contributed to the relatively isolated status of Yeyi within Eastern Bantu. Yeyi has seen extensive influence from surrounding Khoisan languages in its phonology, morphology, and lexicon (

Sommer & Voßen, 1992;

Gunnink et al., 2015;

Gunnink, 2022). If inherited words in the basic lexicon were replaced by loans, this would have obscured the precise Bantu origins of Yeyi. However, horizontal Khoisan influence was not strong enough to obscure Yeyi’s Bantu origins. In the 100-word list used for our phylogeny, eight Yeyi words have an identifiable Khoisan origin. These words all come from languages of the Khoe branch of the Khoe–Kwadi family and are listed in

Table 1. Five of these concepts are also represented by a synonym in Yeyi with a clear Bantu origin, as shown by its corresponding Bantu lexical reconstruction, either in the same doculect as the Khoisan loan or in a different doculect. So, even though Khoisan influence on Yeyi was strong enough to interfere with its basic vocabulary, most of its basic vocabulary of Bantu origin is also still maintained. Furthermore, as mentioned above, Yeyi has acquired many lexical innovations in its basic vocabulary which do not have an identifiable Khoisan origin.

Having shown that language contact did not affect Yeyi’s basic vocabulary strongly enough to account for its position as an evolutionary “loner” within Wider Eastern Bantu, we therefore consider these results as robust and now turn to the interpretation of this linguistic classification in terms of historical scenarios.

5. Discussion

Firstly, the analysis of Yeyi as a member of the Wider Eastern Bantu branch allows us to identify the homeland of the Wider Eastern Bantu clade as the most likely area from where ancestral Yeyi speakers would have migrated into their current habitat. This Wider Eastern Bantu homeland would be situated somewhere in the Katanga region of what is now the southern DRC (see map in

Figure 2), which is where the center of highest diversity within the Wider Eastern Bantu sub-clade including Yeyi is situated. What we call Wider Eastern Bantu corresponds largely to branch 11 in

Grollemund et al.’s (

2015,

2023) phylogeny, whose homeland they situate to the east of Lake Tanganyika, from where speakers of “Sabi-Botatwe” languages, similar to our Bemba–Bisa–Lamba and Bantu Botatwe branches, expanded in a southwestern direction. This also corresponds to the “Osthochland-Gruppe” in the lexicostatistical classification of

Heine et al. (

1977), though not exactly, as the latter also includes Luba of Kasai (DRC) and the zone D languages of eastern DRC.

Heine et al. (

1977, p. 65) situate the homeland of this subgroup, from where most of eastern and southern Africa was colonized, between the Kasai and Lualaba Rivers, i.e., an area roughly corresponding to the territories of the modern Kasai, Kasai-Central, Kasai-Oriental, Sankuru, and Lomami provinces of the DRC (formerly Kasai-Occidental and Kasai-Oriental). This is slightly to the north of Katanga, where we situate the Wider Eastern Bantu homeland, and immediately to the east of where

Pacchiarotti et al. (

2019) situate the West–Coastal Bantu homeland. Southwestern Bantu’s center of origin would, then, have been somewhere south of the West–Coastal Bantu homeland and west of our Wider Eastern Bantu homeland.

According to

Heine et al. (

1977, p. 65), the fragmentation of the “

Osthochland-Nukleus” some two millennia ago must have been explosive and led in a very short time to the “flooding” (“

überfluten”) of the vast area between the Laikipia Plateau in Kenya and the Karoo in South Africa by the different subgroups emerging from that “punctuational burst” (cf.

Atkinson et al., 2008). One of these early offshoots may have been the most recent common ancestor of Yeyi and its extinct closest relatives.

However, the exact timing of the Yeyi migration into southern Africa is difficult to establish. On the one hand, the lack of genealogical affiliation between Yeyi and its geographic neighbors of the Bantu Botatwe, Bemba–Bisa–Lamba, or Southwestern Bantu subgroups clearly supports a scenario of a separate migration. If this migration happened relatively recently, we would expect Yeyi to have clearly identifiable sister languages within Wider Eastern Bantu as a whole. Other cases of such recent long-distance migrations of speech communities originated in nineteenth-century CE South Africa, from where Sotho-speaking groups ancestral to Lozi speakers migrated to Western Zambia, and Nguni-speaking groups ancestral to Ndebele migrated to western Zimbabwe. The modern Lozi language, however, still shows a very clear genealogical affiliation to the Sotho language cluster of Southern Africa, and Zimbabwean Ndebele is closely embedded in the Nguni cluster (see

Figure 1). If the Yeyi language would also result from such a relatively recent, relatively long-distance migration, it would be expected to still show an identifiable affiliation to specific Eastern Bantu languages, which is not the case.

On the other hand, if the ancestors of modern-day Yeyi speakers entered southern Africa through a relatively early migration, this would not only explain its lack of close affiliation to its neighbors, but would also account for the accumulation of linguistic differences between Yeyi and its Narrow Eastern Bantu relatives.

The lack of close genealogical relatives to Yeyi, either within the general geographic vicinity or within Wider Eastern Bantu, also raises the question of how the Yeyi cluster has apparently resisted diversification. One possibility is that the Yeyi speech communities were surrounded by other ethnolinguistic groups, which prevented them from migrating and loosening their social and linguistic bonds. Another possibility is that the Yeyi cluster did once belong to a larger and more diverse group of languages, but that its putative earlier sister languages disappeared through language shift. This would be especially likely if the Yeyi resulted from a relatively early migration, where surrounding Bantu languages arrived as part of a separate and more recent expansion. Among the possible targets of shift are Bantu Botatwe languages, which border on Yeyi in the northeast, and languages of the Luyana cluster (K30), spoken to the north of Yeyi. Both groups are also among the languages that have previously been proposed as Yeyi’s possible relatives (see

Section 2). While a close genealogical relationship between Yeyi and either Luyana or Bantu Botatwe is not supported in our phylogeny, it is possible that the linguistic similarities that exist are rather the result of a substrate of a now extinct Bantu language closely related to Yeyi.

Yeyi as the remnant of an early migration phase, partially replaced by later migrants speaking different Bantu languages, is similar to other scenarios of spread-over-spread proposed in different parts of the Bantu-speaking area. In the Congo rainforest, two separate population expansions were separated by a population collapse in the first millennium CE, suggesting that many of the modern-day Bantu languages spoken in the area derive from this second population expansion, with many of the languages spoken by the first Bantu migrants having gone extinct (

Seidensticker et al., 2021;

Bostoen et al., in press). In southern Africa, based on mismatches between archaeology and linguistic phylogeny,

Gunnink et al. (

2023) propose a spread-over-spread scenario for the Shona language community. Judging from their ceramic traditions (

Huffman, 2007), the ancestors of modern-day Shona speakers would have arrived in southern Africa in the first millennium CE as part of the earliest wave of Bantu Expansion. However, judging from the phylogeny of Southern Bantu, of which Shona is integral part (see also

Figure 1), and the fact that the ceramic traditions of other Southern Bantu speech communities do not extend back beyond 1000 CE (

Schoeman, 2013;

Mitchell, 2024), Shona ancestors likely shifted to ancestral Southern Bantu languages when these were introduced as part of a later wave of Bantu Expansion in the second millennium CE. In the same vein, comparing archaeological and linguistic data,

Phillipson (

1977) has already suggested that modern-day Eastern Bantu speakers more generally trace their origin to the Late Iron Age rather than the Early Iron Age.

The case of Yeyi could represent another instance of an early Bantu migration, possibly followed by more recent migrations of communities speaking different Bantu languages. However, unlike the ancestors of modern-day Shona speakers, the ancestors of modern-day Yeyi speakers did not shift to more recently introduced Bantu languages of newcomers such as Southern Bantu or to expanding languages of Bantu-speaking groups settled earlier on, such as Bantu Botatwe or Luyana. Yeyi forebears stuck to their own ancestral language, while neighboring communities speaking closely related languages or possibly even part of the ancestral Yeyi speech community itself did shift and were gradually assimilated into those language communities. As a result, Yeyi ended up as a clade of its own within the Wider Eastern Bantu sub-branch of the Bantu family tree’s major Savanna Bantu branch.

This hypothesis of Yeyi as the sole survivor of an early phase of Bantu Expansion in the wider vicinity of the Okavango Delta needs further testing, on the basis of both other types of historical linguistic evidence and bodies of evidence from other disciplines, such as archaeology and population genetics. For instance, future research into the material culture of modern or historically attested Yeyi communities, such as ceramic traditions, could shed further light on their historical development, continuity and migration. Furthermore, in order to test the hypothesis that Yeyi’s putative earlier sister languages disappeared as the result of language shift, a potential Yeyi-like substrate could be investigated in Bantu languages spoken to the northeast of modern-day Yeyi communities.