I, as a Fault—Condemnation of Being and Power Dynamics in the Parent-Child Interaction †

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Approaching Child Abuse

1.2. Verbal Violence Framework and Objectives of the Study

“Speech acts of condemnation, such as provocation, threats, reproaches, or insults, are at the core of perceived effects of verbal violence because they aim to affect the other person, to alter their sense of security, dignity, and/or social esteem, and to demean them by asserting power through pragmatic means. These acts are often accompanied by argumentative devices that legitimise the judgements issued (“I treat you this way because…”)”.

“Criticism happens when someone verbally attacks their partner, placing the blame for whatever problem they are experiencing inside the partner’s character. Instead of complaining about the situation and offering a way to make things better, the user of criticism communicates a belief that the problem is occurring because of a defect in their partner. Words such as “always” and “never” frequently appear in criticism-based statements”.

2. Studying Reported Speech Acts in Testimonies: Methodology of Collection and Analysis

2.1. Sampling Methodology

2.2. Delimitating the Parent’s Reported Speech

- Acts of insult, denigration, reproach, etc., reported without “the linguistic context containing any semes directly pertaining to the speech act” (Rosier, 1999, p. 129).[1] Whether it was humiliation in public places, insults, denigration, psychological pressure or repeated crises, coming to his house became an ordeal.Qu’il s’agisse d’humiliations dans des lieux publiques, insultes, dénigrements, pressions psychologiques et crises à répétition, venir chez lui devenait un calvaire. (Albane)8

- Cases in which identifying the enunciative source and/or interpreting the segment as reported speech present challenges9:[2] In primary school, my father hit me when I “made him angry”En primaire, mon père me frappait lorsque je “le mettais en colère” (Chiara)[3] My brother had serious learning and behavioural disorders. So for me, it was better not to “make things worse”. Not to make waves. Not to be an extra burden.Mon frère avait de gros troubles de l’apprentissage et du comportement. Alors moi, il valait mieux que j’en “rajoute pas”. Que je ne fasse pas de vagues. Que je ne sois pas un fardeau supplémentaire. (Théa).

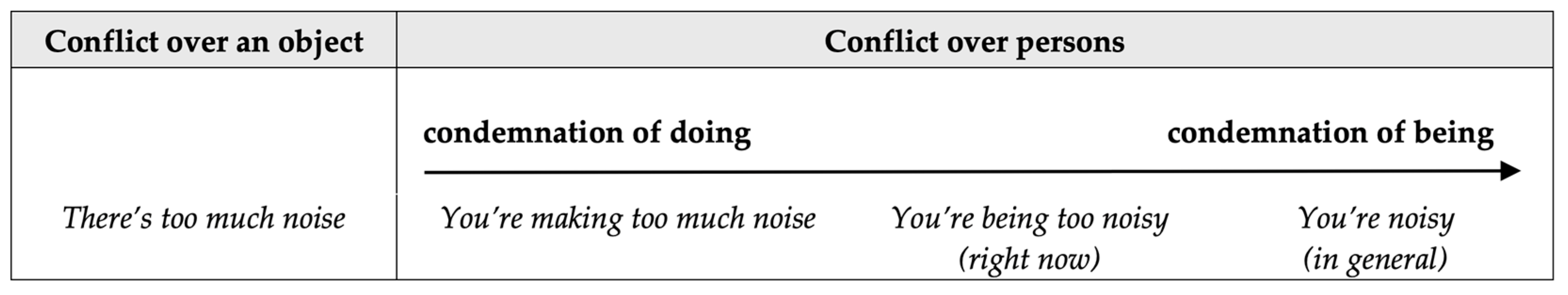

2.3. Categorising Reported Speech Acts as Condemnation Acts

“[…] the viewpoint of the message’s recipient, in our opinion, is the only one that allows us to account for what actually happens in an interaction. Whether we deem a statement to be an insult or not, we can hardly argue that there is verbal violence if its recipient does not feel insulted. Tolerance for confrontation varies greatly among individuals and communities, hence our only analytical choice is to consider that it is the reaction to such acts by an addressee that “constructs” the threatening act, even though the act’s intention often aligns with its perception”.

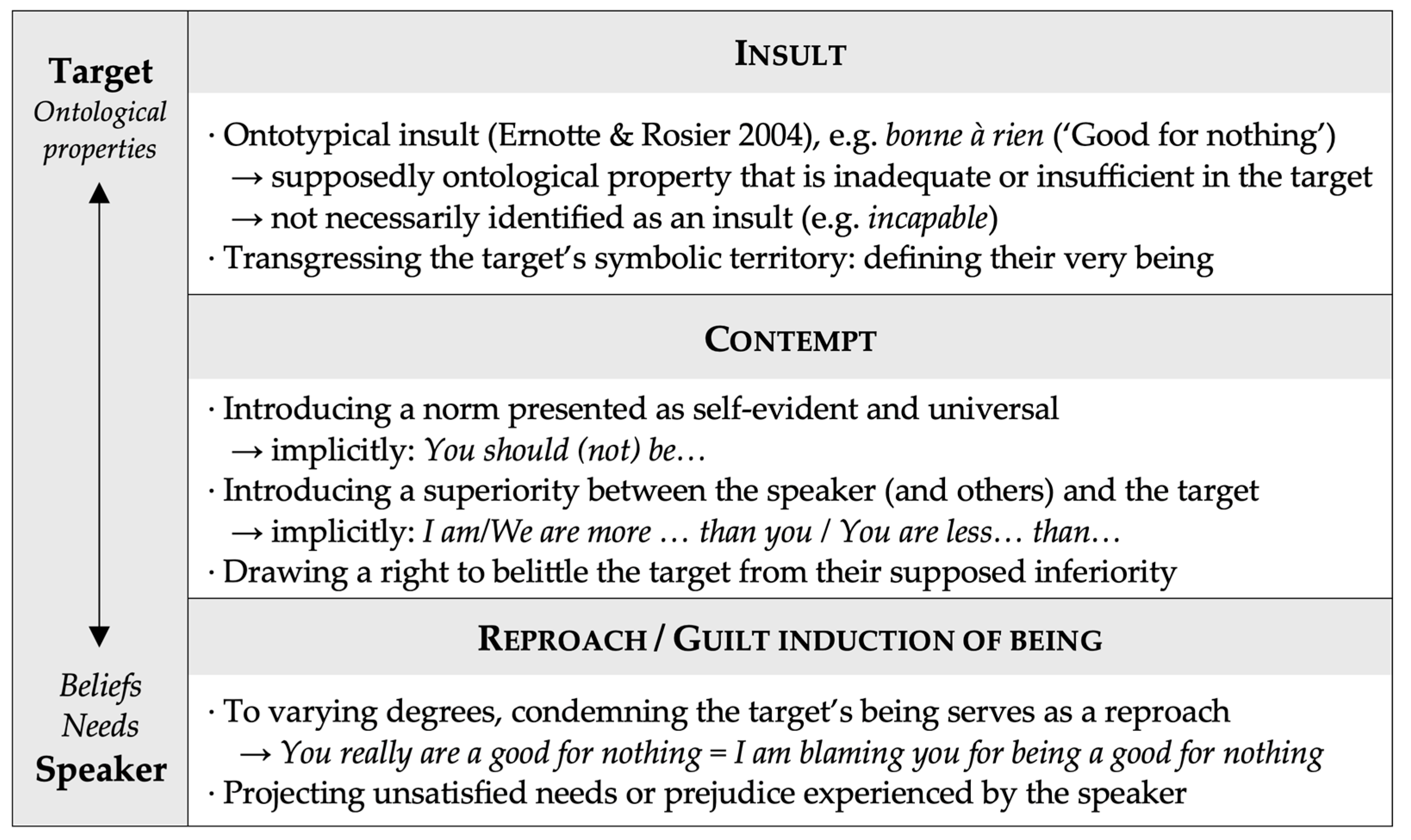

3. Between Insult, Contempt, and Reproach: Discursive Modalities of the Condemnation of Being

3.1. Contempt for the Other: Essentialisation and Downgrading

[4] He often used to say to us, “You really are good for nothing! You’ll never get anywhere in life. Maybe you can clean the toilet at my job!” […] However, to this day, when I do something (I graduated with a Bac+2 [=two years of higher education] in 2014), and I’ve been cosplaying for several years, it is worthless in his eyes. I’m nothing. I’m still a good for nothing to him because I’m unemployed…Il nous disait souvent “t’es vraiment bon.ne à rien! T’arriveras jamais à quoi que ce soit dans la vie.. Tu pourras peut-être nettoyer les chiottes à mon boulot!” […] Cependant, encore aujourd’hui, quand je réalise quelque chose (j’ai validé un bac+2 en 2014), et je fais du cosplay depuis plusieurs années, ça n’a aucune valeur à ses yeux. Je ne suis rien. Je reste une bonne à rien pour lui parce que je suis sans emploi… (Mollie)[5] He’d make me work on my maths for hours and when I didn’t understand, he’d call me a “moron” and shake me by the arm—always that arm…. […] More generally, it was me who wasn’t good enough.Il me faisait travailler mes maths pendant des heures et lorsque je ne comprenais pas, il m’insultait de “conne” et me secouait par le bras—toujours ce bras… […] Plus généralement, c’était moi qui n’était pas assez bien. (Chiara)[6] He took advantage of a moment when I was burnt out at work to tell me that I was a good for nothing anyway etc…Il a profité d’un moment où j’ai fait un burn out dans mon boulot pour me dire que de toute façon je ne suis qu’un bon à rien etc… (Matthias)[7] “We wanted a boy, you were our last attempt”. Hearing night and day that we were incapable, “I should’ve cut my balls off when I see these sub-sh.”. destroyed my school education.“On voulait un garçon, t’étais notre dernière tentative”. Entendre nuit et jour que nous étions des incapables, “J’aurai dû me couper les couilles quand je vois ces sous-m.. “ a détruit ma scolarité. (Jane)[8] Then I lived with my mother, who taught us with “You’re retarded”, “What have I done to produce such morons?!”, “Your father doesn’t love you, he doesn’t give a fuck about his children”.J’ai vécu par la suite avec ma mère qui nous éduquait à coup de “Tu es retardée”, “Qu’est-ce que j’ai fait pour pondre des abrutis pareils ?!”, “Votre père ne vous aime pas, il en a rien à foutre de ses enfants”. (Gabrielle)

3.2. Performativity of the Indirect Condemnation Act

“In an asymmetrical relationship, verbal violence realised through indirect speech acts is more pronounced when the person in the higher position (the parent, teacher, superior, etc) holds symbolic power. It is challenging for the person in the lower position (the child, student, employee, etc) to respond without fearing potential consequences, whether affective or professional”.

[9] Then comments about my appearance: “Cover your legs, they’re too skinny”. “You were so ugly as a baby”. And in the middle of my teenage crisis and so of my insecurities, I hear from her mouth, “You may not be beautiful, but you’re intelligent” (I was a good student).Puis des remarques sur mon physique: “cache tes jambes, elles sont trop maigres”. “Tu étais si laide bébé”. Et en pleine crise d’ado et donc de complexes, j’entends de sa bouche “Tu n’es peut-être pas belle mais tu es intelligente” (j’étais bonne élève). (Julie)

- “First, an argument p is put forward for a conclusion r. The speaker may either express agreement with p (acknowledging its relevance or truth value; Moeschler & De Spengler, 1981, p. 101) or, more modestly, suspend their judgement (Léard & Lagacé, 1985, pp. 14–15); in either case, p is not contested.

- p is followed by another argument q for a non-r conclusion; q is typically introduced by an oppositional connector (typically “mais” [in French, i.e., ‘but’]). This second argument is presented as outweighing the first (the concessive movement thus leads to the conclusion of non-r) […]”.

3.3. Stratification of the Condemnation of Being

[10] Then I lived with my mother, who taught us with “You’re retarded”, “What have I done to produce such morons?!”, “Your father doesn’t love you, he doesn’t give a fuck about his children”.J’ai vécu par la suite avec ma mère qui nous éduquait à coup de “Tu es retardée”, “Qu’est-ce que j’ai fait pour pondre des abrutis pareils ?!”, “Votre père ne vous aime pas, il en a rien à foutre de ses enfants”. (Gabrielle)

4. Constructing the Being at Fault: Negation of Otherness and Disruption of the Authority Relationship

4.1. Reproach and Guilt Induction: From Otherness to Oneself

4.2. Reasons for the Guilt Induction of Being

[12’] I’d discovered that my mother was going through all my messages and that she’d done the same with my sister’s mailbox and she was really angry about what she’d found there: messages from my sister saying we were unhappy./So her reaction to that was to punch me in the face. Which stunned me for a moment. My brother held her back or she’d have jumped on me. She was drooling, shouting that I was just a slut, a real bitch, vile and ungrateful.J’avais découvert que ma mère fouillait tous mes messages et qu’elle avait fait de même avec la messagerie de ma sœur et elle était vraiment en colère de ce qu’elle y avait trouvé: des messages de ma sœur disant que nous étions malheureux./Alors la réaction qu’elle a eu face à ça et de me coller une droite en pleine face. Me sonnant pendant un instant. Mon frère l’a retenu sinon elle me sautait dessus. Elle bavait, criant que j’étais qu’une salope, une vraie connasse, immonde et ingrate. (Gabrielle)

4.3. Towards a Disruption of Interactional Dynamics

[18] But being your mother’s shrink in the evening, with her nose in her bottle, gives a bitter taste of life as early as 6 years old, just as she experienced itMais être la psy de sa mère le soir, le nez dans sa bouteille, donne dès ses 6 ans un goût amer de la vie, autant qu’elle le vivait. (Jane)[19] When I was a kid, I quickly became the man of the house, at least when she was single. Which means I became her confidant, sharing all her troubles. One evening when I was about 6 or 7, we were sitting on the sofa, she took a handful of pills and told me “goodbye”. Obviously I panicked, and when I tried to call 911 she told me off, because “it was just a joke to see if I loved her”.Quand j’étais petit, je suis rapidement devenu l’homme de la maison, en tout cas dans les moments où elle était célibataire. Ce qui signifie que je suis devenu son confident en partageant tous ses malheurs. Un soir, vers 6 7 ans, nous étions assis sur le canapé et elle a prit une poignée de cachets en me disant “Adieu”. Forcément j’ai paniqué et lorsque j’ai voulu appeler les pompiers elle m’a disputé, car « ce n’était qu’une blague pour voir si je l’aimais ». (Matthias)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | All translations will be mine throughout the article unless specified otherwise |

| 2 | The Parents toxiques corpus was compiled as part of a doctoral research project supervised by Julien Longhi and Laurence Rosier. The sample was collected for a Master’s research project supervised by Claudine Moïse (Moreau Raguenes, 2021). |

| 3 | https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/article_lc/LEGIARTI000038749626 (accessed on 15 June 2024). |

| 4 | “Chapitre II: Des atteintes à l’intégrité physique ou psychique de la personne (Articles 222-1 à 222-67)” https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/section_lc/LEGITEXT000006070719/LEGISCTA000006149827/#LEGISCTA000006149827 (accessed on 15 June 2024). |

| 5 | I choose to use the notion of “condemnation act” (Laforest & Moïse, 2013 notably, ’actes de condamnation’ in French) rather than face-threatening acts to refer to acts that undermine the addressee’s face (Goffman, 1956) and identity. This choice emphasises the disqualification of the target—disqualification not being constitutive of all face-threatening acts (e.g., an injunction not accompanied by disqualifying acts). |

| 6 | Of course, these parameters vary depending on the child’s age. |

| 7 | The URL and publication date of the testimonies will not be indicated for ethical reasons. |

| 8 | Emphasis (in bold) is always my addition; in the quotes, italics always come from the cited text. Spelling and punctuation will not be modified in the cited corpus excerpts. |

| 9 | In [2], Chiara could be reporting a reproach her father directed to her (e.g., You make me angry), in which case the segment enclosed in quotation marks would be reported speech. Alternatively, she might be using quotation marks to express critical distance towards the causal link represented. In [3], it could be an injunction (e.g., Don’t make things worse) reported in free indirect speech, but the boundary between what the parent said and what was understood and internalised by the speaker (“Not to make waves. Not to be an extra burden”.) is porous. |

| 10 | I use the term enunciator because the speech acts analysed are in reported speech: the parent is the enunciative source but does not perform the locutionary act. The term speaker always refers to the authors of the testimonies. |

| 11 | However, argumentative strategies that allow the narrators to express contempt in interaction can be identified through analysis (see Baider, 2020 for instance). |

| 12 | In the English-speaking literature, a similar notion has been proposed—mock politeness (Taylor, 2015, for instance). |

| 13 | I choose to use the term reproach rather than complaint because, as pointed out by Laforest (2002, p. 1596) “the meaning of the term ‘complaint’ is broader than that of the French term ‘reproche’, […] which refers only to dissatisfaction addressed to the person held to be responsible for deviant behavior”. |

| 14 | See the model of the escalation of acute verbal violence (“violence verbale fulgurante” in French) in Moïse et al. (2019, p. 13). |

References

- Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ayimpam, S. (2015). Enquêter sur la violence. Civilisations. Revue internationale d’anthropologie et de sciences humaines, 64, 3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baider, F. (2020). Obscurantisme et complotisme: Le mépris dans les débats en ligne consacrés à la vaccination. Lidil. Revue de linguistique et de didactique des langues, 61, 7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard Barbeau, G., & Moïse, C. (2020). Introduction—Le mépris en discours. Lidil. Revue de Linguistique et de Didactique des Langues, 61. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/lidil/7264 (accessed on 6 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bernard Barbeau, G., & Moïse, C. (2023). Mépris. In N. L. Bailly, & C. Moïse (Eds.), Discours de haine et de radicalisation: Les notions clés (pp. 277–281). ENS Éditions. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charaudeau, P. (2011). Du contrat de communication en général. In Les médias et l’information. L’impossible transparence du discours (pp. 49–55). De Boeck Supérieur. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/les-medias-et-l-information--9782804166113-page-49.htm (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Clancy, B. (2011). Complementary perspectives on hedging behaviour in family discourse: The analytical synergy of variational pragmatics and corpus linguistics. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 16(3), 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doury, M., & Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. (2011). La place de l’accord dans l’argumentation polémique: Le cas du débat Sarkozy/Royal (2007). A Contrario, 16(2), 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsdóttir, J. (2007). Research with children: Methodological and ethical challenges. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 15(2), 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernotte, P., & Rosier, L. (2004). L’ontotype: Une sous-catégorie pertinente pour classer les insultes? Langue française, 144(1), 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracchiolla, B., Lorenzi Bailly, N., Moïse, C., & Romain, C. (2023). Violence verbale. In N. L. Bailly, & C. Moïse (Eds.), Discours de haine et de radicalisation: Les notions clés (pp. 299–307). ENS Éditions. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1956). The Presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J., & Gottman, J. (2017). The natural principles of love. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(1), 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J. M., Cole, C., & Cole, D. L. (2019). Four horsemen in couple and family therapy. In J. L. Lebow, A. L. Chambers, & D. C. Breunlin (Eds.), Encyclopedia of couple and family therapy (pp. 1212–1216). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. (1997). L’énonciation: De la subjectivité dans le langage (3rd ed.). Armand Colin. [Google Scholar]

- Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. (2010). L’impolitesse en interaction. Aperçus théoriques et étude de cas. Lexis. Journal in English Lexicology, HS 2, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopelman, L. (2000). Children as research subjects: A dilemma. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy: A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine, 25(6), 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koselak, A. (2005). Mépris/dédain, deux mots pour un même sentiment? Lidil. Revue de Linguistique et de Didactique des Langues, 32, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousholt, D., & Juhl, P. (2023). Addressing ethical dilemmas in research with young children and families. Situated ethics in collaborative research. Human Arenas, 6(3), 560–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic patterns. University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laforest, M. (2002). Scenes of family life: Complaining in everyday conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, Negation and Disagreement, 34(10), 1595–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforest, M., & Moïse, C. (2013). Entre reproche et insulte, comment définir les actes de condamnation? In B. Fracchiolla, C. Moïse, C. Romain, & N. Auger (Eds.), Violences verbales. Analyses, enjeux et perspectives (pp. 85–105). Presses universitaires de Rennes. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01969711 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Laforest, M., & Vincent, D. (2004). La qualification péjorative dans tous ses états. Langue Française, 144(1), 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforest, M., & Vincent, D. (2006). Les interactions asymétriques. Ed. Nota Bene. [Google Scholar]

- Léard, J.-M., & Lagacé, M. F. (1985). Concession, restriction et opposition: L’apport du québécois à la description des connecteurs français. Revue québécoise de linguistique, 1(15), 11–49. Available online: https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/rql/1985-v15-n1-rql2925/602548ar/ (accessed on 6 March 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Longhi, J. (2013). Essai de caractérisation du tweet politique. L’Information Grammaticale, 136(1), 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi Bailly, N., & Moïse, C. (Eds.). (2021). La haine en discours. Le Bord de L’eau. [Google Scholar]

- Moeschler, J., & De Spengler, N. (1981). Quand même: De la concession à la réfutation. Cahiers de linguistique française, 2, 93–112. Available online: https://www.unige.ch/clf/fichiers/pdf/07-Moeschler_nclf2.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Moeschler, J., & De Spengler, N. (1982). La concession ou la réfutation interdite. Cahiers de linguistique française, 4, 7–36. Available online: https://www.unige.ch/clf/fichiers/pdf/02-Moeschler_nclf4.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Moïse, C. (2020). Pour (re)venir à une sociolinguistique du sujet et de la subjectivité. In K. D. Léonard, & V. Rose-Marie (Eds.), Appropriation des langues et subjectivité. Mélanges offerts à Jean-Marie Prieur par ses collègues et amis (pp. 59–70). L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Moïse, C., Meunier, E., & Romain, C. (2019). La violence verbale dans l’espace de travail: Analyses et solutions (2nd ed.). Bréal. [Google Scholar]

- Moïse, C., & Oprea, A. (2015). Présentation. Politesse et violence verbale détournée. Semen. Revue de Sémio-Linguistique des Textes et Discours, 40, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau Raguenes, R. (2021). La construction du sujet agentif sur Parents toxiques: Analyse discursive d’un (re)maniement de soi par le témoignage de maltraitance parentale [Master’s dissertation, Université Grenoble Alpes]. Available online: https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-03610362 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Moreau Raguenes, R. (2022). (Dé)montrer la maltraitance parentale sur Instagram: Étude argumentative du récit extime catégorisant. Cahiers de Narratologie. Analyse et Théorie Narratives, 42, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau Raguenes, R. (2024a). L’être comme fautif. Actes de condamnation, altérité et rapport de places dans l’interaction parent-enfant. SHS Web of Conferences, 191, 01009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau Raguenes, R. (2024b). Saisir la maltraitance parentale. Une approche discursive. In S. Wharton, S. Vernet, & M. Gasquet-Cyrus (Eds.), La sociolinguistique, à quoi ça sert? Sens, impact, professionnalisation (pp. 163–177). Presses Universitaires de Provence. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04831025 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Morel, M.-A. (1996). La concession en français. Ophrys. [Google Scholar]

- Neuburger, R. (2008). L’art de culpabiliser. Payot. [Google Scholar]

- Rosier, L. (1999). Le discours rapporté: Histoire, théories, pratiques. Duculot. [Google Scholar]

- Rosier, L. (2008). Le discours rapporté en français. Ophrys. [Google Scholar]

- Rosier, L. (2009). Petit traité de l’insulte. Esprit libre. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, J. R. (1982). Sens et expression: Études de théorie des actes de langage (J. Proust, Trans.). Les Éditions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. (2015). Beyond sarcasm: The metalanguage and structures of mock politeness. Journal of Pragmatics, 87, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hooland, M. (Ed.). (2005). Psychosociolinguistique: Les facteurs psychologiques dans les interactions verbales. L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hooland, M. (2008). L’enfant et sa stratégie discursive d’adaptation en situation de maltraitance familiale, approche psychosociolinguistique des interactions verbales maltraitantes. In C. Moïse, N. Auger, B. Fracchiolla, & C. Romain (Eds.), La violence verbale. Tome 2. Des perspectives historiques aux expériences éducatives (pp. 215–236). L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, D. (2013). L’agression verbale comme mode d’acquisition d’un capital symbolique. In B. Fracchiolla, C. Moïse, C. Romain, & N. Auger (Eds.), Violences verbales. Analyses, enjeux et perspectives (pp. 37–54). Presses Universitaires de Rennes. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, D., Laforest, M., & Turbide, O. (2008). « Pour un modèle fonctionnel d’analyse du discours d’opposition: La trash radio ». In C. Moïse, N. Auger, B. Fracchiolla, & C. Schulz-Romain (Eds.), La violence verbale. L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreau Raguenes, R. I, as a Fault—Condemnation of Being and Power Dynamics in the Parent-Child Interaction. Languages 2025, 10, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10030054

Moreau Raguenes R. I, as a Fault—Condemnation of Being and Power Dynamics in the Parent-Child Interaction. Languages. 2025; 10(3):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10030054

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreau Raguenes, Rose. 2025. "I, as a Fault—Condemnation of Being and Power Dynamics in the Parent-Child Interaction" Languages 10, no. 3: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10030054

APA StyleMoreau Raguenes, R. (2025). I, as a Fault—Condemnation of Being and Power Dynamics in the Parent-Child Interaction. Languages, 10(3), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10030054