1. Introduction

This work investigates the adverbs of repetition in Vietnamese,

lại and

nữa, and proposes syntactic accounts for them. The adverb

lại can be used alone or with the particle

nữa to express the meaning of ‘‘again’’ (

Nguyễn, 1997), as shown in (1).

The word

lại in Vietnamese can be used as a verb meaning “to come”, an adverb, a modal particle conveying the speaker’s attitude, or a sub-element in a sentence connector (

Thompson, 1987;

Nguyễn, 1997;

Trần, 2023, and others). See (2a)–(2d).

| (2) | a. | Em | hãy | lại | đây | với | anh! | | |

| | | you | IMP | come | here | with | me | | |

| | | ‘Come here to me, please!’ (Trần, 2023, p. 252) | | |

| | b. | Tôi | lại | yêu | anh ấy | như | ngày | nào. | |

| | | I | again | love | him | as | day | which | |

| | | ‘I fell in love with him again like before.’ (Trần, 2023, p. 255) | |

| | c. | Vì sao | khi | con | kéo | đàn, | bà | |

| | | why | when | I | play | violin | grandma | |

| | | lại | khóc | vậy | mẹ? | | | |

| | | LAI | cry | such | mother | | | |

| | | ‘Why does grandma cry when I play the violin, mom?’ (Trần, 2023, p. 261) |

| | d. | Ngược lại / | Trái lại, | anh ta | rất | chăm chỉ. |

| | | however | however | he | very | hard-working |

| | | ‘However, he is very hard-working.’ (Trần, 2023, p. 263) |

In this work, we focus on the repetitive use of

lại. It has been pointed out that different syntactic positions of

lại result in different readings (

Thompson, 1987;

Nguyễn, 1997;

Phan, 2013, etc.); see (3a,b). When the adverb

lại precedes a verb, it has a repetitive reading. When the adverb

lại follows a verb, it can only yield a restitutive reading. According to

Phan (

2013), in (3a), the entire event of the subject writing a letter is repeated, while, in (3b), only the result state of the event (i.e., the letter having been written) re-occurs.

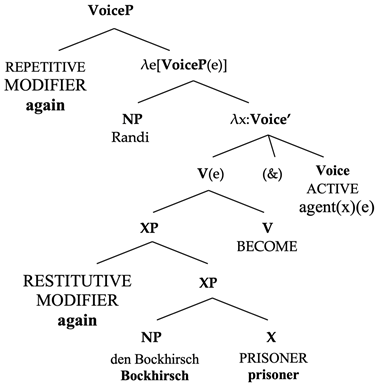

2,3Stechow (

1996) postulates a structural analysis for the ambiguous readings of the adverb

wieder, “again”, in German and argues that the ambiguity of

wieder arises from different modifying scopes.

Beck and Johnson (

2004) further apply this analysis to the ambiguity of the adverb

again in English (see also

Beck & Snyder, 2001;

Beck, 2006). Inspired by these analyses, we propose that the preverbal

lại in Vietnamese adjoins to vP. The modifying scope of the preverbal

lại can be the entire event or a result state of the event. This gives rise to the two readings, namely the repetitive and restitutive readings. In addition, we argue that the postverbal

lại adjoins to VP, and it can only modify the result state of the predicate vP. Therefore, it only yields the restitutive reading. We also show that syntactic tests support the proposed analyses of the preverbal

lại and the postverbal

lại.

The word

nữa, which occurs after the predicate, expresses the meaning “more, in addition, also”, as shown in (4). It can also denote the repetition of an event, as in (5).

| (4) | Ông | dùng | cơm | nữa | thôi? |

| | you | have | rice | more | SFP |

| | ‘Are you going to eat more rice?’ (Thompson, 1987, p. 271) |

| (5) | Hôm nay | trời | mưa | nữa | rồi. |

| | today | sky | rain | more | PERF |

| | ‘It is raining again today.’ |

We propose that nữa adjoins to vP, and, furthermore, it triggers the merger of a FocusP on the phrase structure, to which vP moves. This results in the predicate-final position of nữa.

4. The Adverb nữa and Its Syntactic Position

In this section, we discuss the grammatical properties of the adverb

nữa, “more, in addition, also” in Vietnamese. Before delving into the discussion of

nữa, let us introduce the concept of “incremental reading” first.

Tovena and Donazzan (

2008, p. 91) point out that the repetitive adverb

ancora in Italian can give rise to an incremental reading, which means that an activity is incremented by adding subevents measured along a specific dimension. See (27).

| (27) | a. | Maria sta ancora leggendo. |

| | | ‘Maria is still reading.’ |

| | b. | Maria sta leggendo ancora un libro. |

| | | ‘Maria is reading one more book.’ |

The word

ancora in (27a) denotes a meaning comparable to “still,” and the one in (27b) denotes a meaning similar to “more.” The incremental interpretation can be thought of either as a repetition of events or as a continuation of an activity by adding more object units. The adverb

nữa in Vietnamese is quite similar to

ancora, as it yields an incremental reading, shown in (28) and (29).

| (28) | Hôm nay | trời | mưa | nữa | rồi. | | |

| | today | sky | rain | more | PERF | | |

| | ‘It is raining again today.’ | | |

| (29) | Nam | có thể | ăn | một | bát | cơm | nữa. |

| | Nam | can | eat | one | bowl | rice | more |

| | ‘Nam can eat one more bowl of rice.’ |

Now, we turn to the syntactic position of

nữa. First, similar to the preverbal

lại, the adverb

nữa can occur with a stative or dynamic predicate; see (30) and (31). When it occurs with a stative predicate, the perfect aspect particle

rồi is required, as shown in (31).

| (30) | a. | Nam | hôn | Hoa | nữa. | | [dynamic] |

| | | Nam | kiss | Hoa | more | | |

| | | ‘Nam kissed Hoa again.’ |

| | b. | Nam | đánh | Hoa | nữa. | | [dynamic] |

| | | Nam | hit | Hoa | more | | |

| | | ‘Nam hit Hoa again.’ |

| (31) | a. | Nam | thích | Hoa | nữa | *(rồi). | [stative] |

| | | Nam | like | Hoa | more | PERF | |

| | | ‘Nam likes Hoa again.’ |

| | b. | Nam | lại | béo | nữa | *(rồi). | [stative] |

| | | Nam | again | fat | more | PERF | |

| | | ‘He gets fat again.’ |

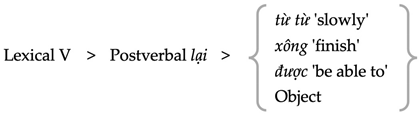

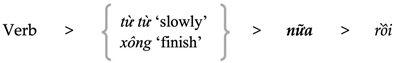

Second,

nữa must follow postverbal manner adverbs, such as, for instance,

từ từ, “slowly”, in (32). The reverse order is ungrammatical.

| (32) | a. | Nam | ăn | từ từ | nữa. |

| | | Nam | eat | slowly | more |

| | | ‘Nam ate slowly too.’ |

| | b. | *Nam | nữa | ăn | từ từ. |

| | | Nam | eat | more | slowly |

Third,

nữa must follow the completive marker

xông, “finish”, as shown in (33).

| (33) | a. | Nam | (còn) | ăn | bánh mì | xông | nữa. |

| | | Nam | even | eat | bread | finish | more |

| | | ‘Nam even finished the bread.’ |

| | b. | *Nam | (còn) | ăn | bánh mì | nữa | xông. |

| | | Nam | even | eat | bread | more | finish |

Fourth,

nữa must precede the perfect aspect marker

rồi. See (34). When the perfect aspect marker precedes

nữa, the sentence is ungrammatical.

| (34) | a. | Hôm nay | trời | mưa | nữa | rồi. |

| | | today | sky | rain | more | PERF |

| | | ‘It is raining again today.’ |

| | b. | *Hôm nay | trời | mưa | rồi | nữa. |

| | | today | sky | rain | PERF | more |

Fifth,

nữa cannot scope over the epistemic modal adverb

chắc chắn, “surely”. For the sentence in (35), only reading 1 is possible, where

nữa is within the scope of

chắc chắn, “surely”. In reading 2,

nữa is intended to scope over the epistemic modal adverb

chắc chắn. This reading is not available.

| (35) | Nam | chắc chắn | ăn | cơm | nữa. |

| | Nam | surely | eat | rice | more |

| | 1. ‘Nam surely ate rice again.’ |

| | 2. *‘Again, Nam surely ate rice.’ |

Sixth,

nữa cannot scope over the negator

không, “not”, as shown in (36). In this sentence, the negator scopes over the particle

nữa in readings 1 and 2, and both readings are acceptable. In reading 3, the negator is intended to fall within the scope of

nữa. However, this reading is unacceptable.

| (36) | Nam | sẽ | không | đi | Mỹ | nữa. |

| | Nam | will | NEG | go | America | more |

| | 1. ‘Nam doesn’t have any intention to go to the US now.’ (“will” > NEG > nữa) |

| | 2. ‘Nam will not go to the US anymore.’ (NEG > “will” > nữa) |

| | 3. *‘Nam again doesn’t have any intention to go to the US.’

(*nữa >NEG/“will”) |

Seventh,

nữa can scope over the quantificational subject of a sentence, as shown in (37). When the quantificational subject

không ai, “nobody”, in (37) scopes over the particle

nữa, reading 1 is obtained. When the particle

nữa scopes over the quantificational subject, reading 2 is obtained. Both readings are acceptable.

| (37) | Không | ai | đến | nữa. | |

| | NEG | who | come | more | |

| | 1. ‘Nobody came again.’ (NP > nữa) |

| | 2. ‘Again, nobody came.’ (nữa > NP) |

Eighth,

nữa can co-occur with the preverbal

lai and the postverbal

lai. When these three adverbial elements appear in the same sentence, as in (38), the sentence is fully grammatical.

| (38) | Nam | lại | sơn | lại | nhà | nữa. |

| | Nam | again | paint | again | house | more |

| | ‘Nam repainted the house again. (He also repainted other stuff)’ |

In summary, the following two sets of properties are observed with

nữa. See (39) and (40). In linear order, the particle

nữa must follow the postverbal manner adverb

từ từ, “slowly”, and the completive marker

xông, “finish”, and precede the perfect aspect marker

rồi. Regarding the scope property of

nữa, it must fall within the scope of the epistemic modal adverb

chắc chắn, “surely”, and the negator

không, “not”. In addition,

nữa may scope over the quantificational subject of a sentence.

| (39) | Linear order |

| | ![Languages 10 00018 i004]() |

| (40) | Scope |

| | a. | chắc chắn, “surely” > nữa |

| | b. | không, “not” > nữa |

| | c. | Quantificational subject > nữa |

| | | nữa > Quantificational subject |

5. The Proposal

Inspired by the structural analysis of

Stechow (

1996), we propose an analysis for the preverbal

lại, the postverbal

lại, and

nữa that is partially structural and partially focus-semantic (see

Beck, 2006;

Ippolito, 2007; and

Csirmaz & Slade, 2020, for more focus-based accounts of repetitive adverbs). We agree with Stechow’s proposal that the different readings of a repetitive adverb result from its syntactic position, rather than lexical ambiguity (see

Dowty, 1979; and

Fabricius-Hansen, 1983, among others). However, the approach we adopt is more flexible, since syntactic adjacency does not completely determine the reading of the adverb in question (for details, see below). We argue that the repetitive adverb can target an element within its c-commanding domain and not only the constituent to which it is directly adjoined.

First, based on our observation of the preverbal

lại (summarized in (18)), we propose that the preverbal

lại adjoins to vP. Semantically, as a focus particle, it can be associated with the entire event, namely vP, or only with the result state of the event, namely VP. This results in two possible readings, i.e., the repetitive reading and the restitutive reading. See the example in (41) and its syntactic structure in (42). Note that, in Stechow’s theory,

wieder (and also the English adverb

again; see

Beck & Johnson, 2004) can only modify the syntactic domain to which it is directly adjoined. However, in the case of Vietnamese (and Mandarin, too; see

Lin & Liu, 2009), non-adjacent focalization is possible. In other words, when

lại is adjoined to vP, focalization of the complement of vP, namely VP, is possible in Vietnamese (and Mandarin). This state of affairs is actually a normal case rather than an exception. An example is the focus adverb

only in English. In the English sentence “

John only bought books”,

only may focalize the verb

bought or the object NP

books. For example, we can have the following two contrasts in mind: “

John only bought books and did not buy other things”, in which case

books is focus-marked; or alternatively, “

John only bought books and did not borrow them”, in which case the verb

bought is focus-marked. Having the English adverb

only as a paradigm example, we claim that the preverbal

lại in Vietnamese is such a focus particle. It can focalize a constituent that is within its c-command domain, immediately adjacent to it or otherwise. We assume that the focalization function of the preverbal

lại is carried out by the probe–goal relation of current syntactic theory, which does not require adjacency.

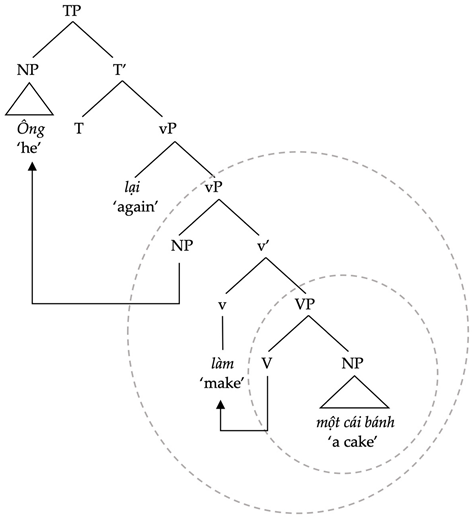

| (41) | Ông | lại | làm | một | cái | bánh. |

| | he | again | make | one | CL | cake |

| | ‘He made a cake again.’ (repetitive or restitutive) |

| (42) | Preverbal lại (circled areas = possible focus targets) |

| | ![Languages 10 00018 i005]() |

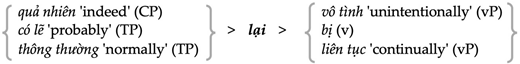

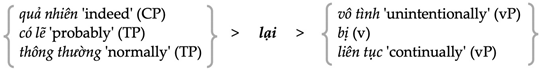

The proposed analysis explains the position of

lại when it co-occurs with other elements, as shown in (16) and repeated in (43).

| (43) | ![Languages 10 00018 i006]() |

The analysis in (42) can account for the structural properties of the preverbal

lại shown in (43). If the preverbal

lại adjoins to vP, it will necessarily be lower than CP-level adverbs and TP-level adverbs, such as

quả nhiên, “indeed”,

có lẽ, “probably”, and

thông thường, “normally”. In addition, since it is on vP and thus precedes the head v, it naturally precedes the passive maker

bị, which is assumed to be the head of a predicate (equivalent to

v) (see

Bruening & Tran, 2015). And, since we assume that the preverbal

lại adjoins to the outer-most layer of vP, it is higher than and, hence, precedes the vP-level adverbs

vô tình, “unintentionally” (vP), and

liên tục, “continually” (vP).

We also noted that the preverbal

lại may occur with dynamic and stative predicates, but the perfect aspect marker

rồi is required when it occurs with a stative predicate, as in (16) and (17), repeated below.

| (44) | a. | Nam | lại | hôn | Hoa. | | [dynamic] |

| | | Nam | again | kiss | Hoa | | |

| | | ‘Nam kissed Hoa again.’ |

| | b. | Nam | lại | đánh | Hoa. | | [dynamic] |

| | | Nam | again | hit | Hoa | | |

| | | ‘Nam hit Hoa again.’ |

| (45) | a. | Nam | lại | thích | Hoa | *(rồi). | [stative] |

| | | Nam | again | like | Hoa | PERF | |

| | | ‘Nam likes Hoa again.’ |

| | b. | Nam | lại | béo | *(rồi). | | [stative] |

| | | Nam | again | fat | PERF | | |

| | | ‘Nam gets fat again.’ |

This phenomenon is similar to the adverb

you, “again”, in Mandarin. When

you, “again”, occurs with a stative predicate, it also needs the presence of the perfect aspect marker

le.

Lin and Liu (

2009, p. 1188) argue that, when

you, “again”, adjoins to a static predicate, it turns the predicate into a dynamic one, namely a change-of-state predicate. We propose that the preverbal

lại exhibits the same function. When it occurs with a static predicate, it turns the predicate dynamic. The presence of the perfect aspect marker

rồi is therefore required to indicate that the predicate is now a dynamic one.

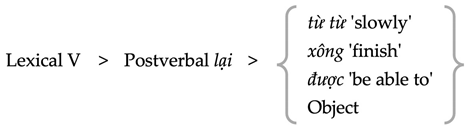

8As to the postverbal

lại, we propose that it adjoins to the lexical VP as its outer-most layer. See (46) and (47) as a demonstration. In sentence (46), the verb

làm, “make”, raises to the head of vP, resulting in the postverbal position of

lại. Since the postverbal

lại only c-commands the VP, its focus domain is limited to the result state of the predicate. Consequently, only the restitutive reading is available for the postverbal

lai. This analysis is also compatible with

Phan’s (

2013) proposal, which posits a projection lower than the vP which denotes the result state of the asserted event, ResultativeP. For simplicity, we use the term VP here.

| (46) | Ông | làm | lại | một | cái | bánh. |

| | he | make | again | one | CL | cake |

| | ‘He made a cake again.’ (only restitutive) |

| (47) | Postverbal lại (circled area: possible focus target) |

| | ![Languages 10 00018 i007]() |

This analysis accounts for the structural properties of the postverbal

lại shown in (24), repeated as in (48).

| (48) | ![Languages 10 00018 i008]() |

First, if the postverbal

lại adjoins to VP, it should precede the object. This accounts for the fact that the postverbal

lại must precede the object in a sentence. Second, if the postverbal

lại adjoins to VP as its outer-most layer, other VP-level elements should be lower than it. This explains the fact that the postverbal

lại precedes the postverbal VP-level manner adverb

từ từ, “slowly.” It also explains the fact that

lại precedes the completive particle

xông, “finish”, and the dynamic modal

được, “be able to.”

Phan (

2013) proposes that the particle

xông and the modal

được are heads of the projection CompletiveP and ResultativeP, respectively, both of which occur between a higher VP (roughly equivalent to vP) and a lower VP of a sentence. In our framework, the postverbal

lại is the outer-most layer of the (generalized) VP; thus, it must be higher than these two elements and precede them. We take

xông as an illustration.

9| (49) | Nam | vừa | [sơn | lại | xông | nhà]. |

| | Nam | just | paint | again | finish | house |

| | ‘Nam just finished the house painting.’ |

| (50) | Co-occurrence of the postverbal lại with the other postverbal element |

| | ![Languages 10 00018 i009]() |

In

Section 3.2, we observed that the postverbal

lại can only be used with a dynamic predicate; it cannot be used with a stative predicate, not even with the perfect aspect marker

rồi. See (19) and (20) above. This can be explained by the proposal that the postverbal

lại adjoins to the projection denoting the result state of a verbal predicate, namely VP. Only a dynamic verbal predicate has a result state. Furthermore, we may assume that the result state that

lại modifies must be the result of an agentive action. Since

rồi only introduces a change-of-state meaning to a stative predicate and no agency is brought in, the addition of

rồi cannot save the sentence from ungrammaticality. A piece of evidence for this proposal is that sentences (17a,b), where the presence of

rồi makes a stative sentence with the preverbal

lại grammatical, can only have the repetitive reading. They do not have the restitutive reading. The lack of an acceptable restitutive reading for (17a,b) clearly originates from the fact that stative predicates do not yield a result state, even when they become dynamic by the function of

rồi.

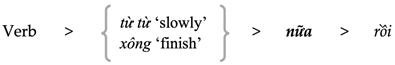

Lastly, we turn to the particle

nữa, which occurs in the predicate-final position. The particle

nữa, in its lexical–semantic nature, is an additive particle that yields an incremental reading. The structural properties of

nữa are shown in (39) and (40), now repeated in (51) and (52).

| (51) | Linear order |

| | ![Languages 10 00018 i010]() |

| (52) | Scope |

| | a. | chắc chắn, “surely” > nữa |

| | b. | không, “not” > nữa |

| | c. | Quantificational subject > nữa |

| | | nữa > Quantificational subject |

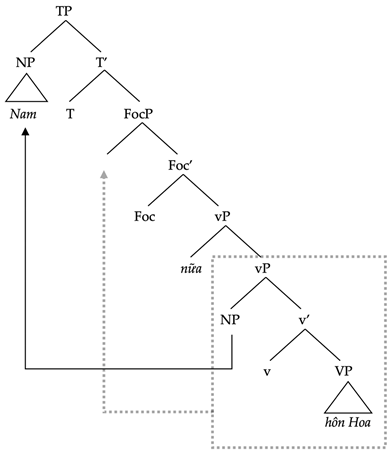

We propose that

nữa adjoins to vP. We further propose that

nữa triggers movement of the vP to a higher functional projection, Spec, FocP, resulting in its being stranded behind the predicate.

10 Following the analysis of light predicate raising of

Simpson (

2001), we assume that the motivation for such movement is to defocus the constituent in question. Examples of such movement include the sentence-final particle

kong, “to speak”, in Taiwanese (

Simpson & Wu, 2002) and the sentence-final deontic modal in Cantonese and a number of Southeast Asian languages (

Simpson, 2001). Let us use the sentence in (30a) as a demonstration, repeated as (53), with (54) as its structural analysis.

| (53) | Nam | hôn | Hoa | nữa. |

| | Nam | kiss | Hoa | more |

| | ‘Nam kissed Hoa again.’ |

| (54) | ![Languages 10 00018 i011]() |

This analysis can account for the structural properties of

nữa shown in (51) and (52). First, if

nữa adjoins to vP, VP-level or VP-internal elements such as

từ từ, “slowly”, and

xông, “finish”, should precede it because the whole VP moves to Spec, FocP, and becomes higher than vP. Second,

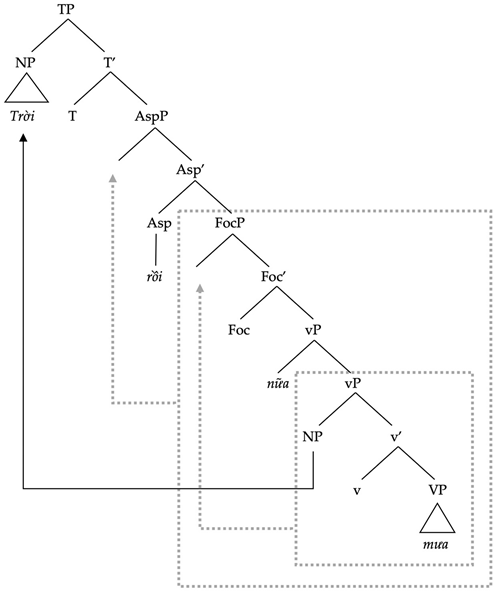

nữa precedes

rồi because

rồi is the head of the projection AspP, which we assume triggers the raising of its complement (FocP in this case) to its specifier. See (55) and (56) for illustration.

| (55) | Trời | mưa | nữa | rồi. |

| | sky | rain | more | PERF |

| | ‘It is raining again.’ |

| (56) | ![Languages 10 00018 i012]() |

Third, if the particle

nữa adjoins to vP, it cannot scope over TP-level elements such as the epistemic modal adverb

chắc chắn, “surely”, and the negator

không, “not”. In addition, as

nữa adjoins to vP, it should fall within the scope of a subject quantifier. So, the scope relation “quantificational subject >

nữa” in (52c) is obtained. On the other hand, a quantificational subject may undergo quantifier lowering (

May, 1985) and assumes its scope position in Spec, vP. In that position, it falls within the scope of

nữa since

nữa adjoins to vP. In this way, the scope relation “

nữa > quantificational subject” is obtained.

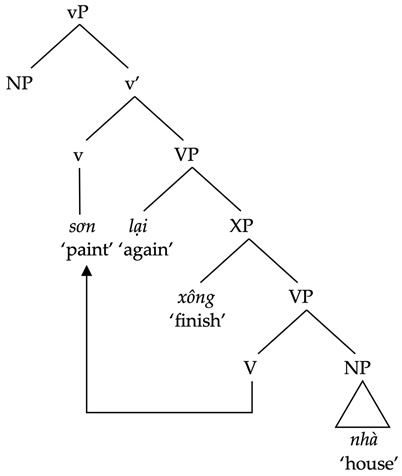

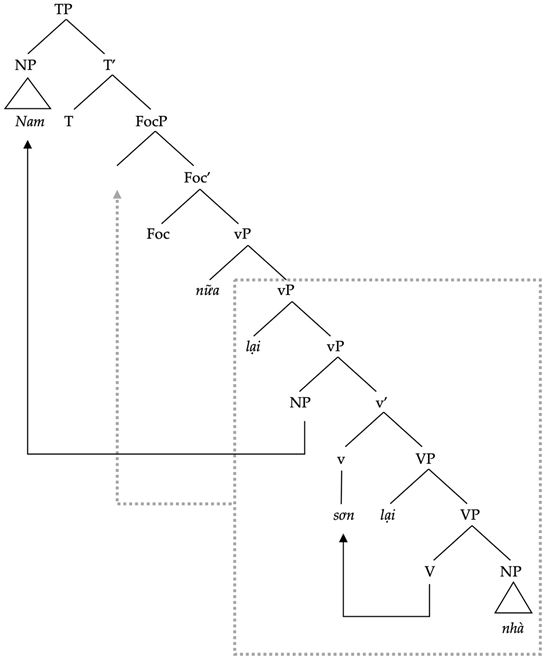

Fourth, our proposal can also account for the co-occurrence of

nữa with the preverbal

lại and the postverbal

lại, as shown in (57) and (58). Sentence (38) is repeated in (57).

| (57) | Nam | lại | sơn | lại | nhà | nữa. |

| | Nam | again | paint | again | house | more |

| | ‘Nam repainted the house again. (He also repainted other stuff)’ |

| (58) | ![Languages 10 00018 i013]() |