1. Introduction

High G maneuvers (9–10 +Gz) in advanced aircraft can cause G-LOC due to reduced cerebral blood flow, leading to 20 s of unconsciousness and minutes-long recovery. This endangers flight safety, especially during precision maneuvers. U.S. Air Force data reports 559 G-LOC cases, with 30–50 annual crashes linked to it. Post-G-LOC symptoms include cognitive impairment, headaches, and vision issues, highlighting the need for better pilot training to mitigate risks.

Real-world flight training is crucial for enabling pilots to develop the ability to withstand high-G loads and reduce the risk of G-LOC. However, this training entails inherent safety risks, and the rapid variations in acceleration make it difficult to measure the forces experienced precisely. This challenge complicates the assessment of training program effectiveness. To address these limitations, high-performance human centrifuges (HPHC) have emerged as invaluable tools for simulating high-G conditions in a controlled environment. By providing realistic high-G exposures, HPHC allows pilots to gradually adapt to the physiological stresses of high-G environments, thereby improving their tolerance and reducing the incidence of G-LOC during actual flights.

HPHC training is typically overseen by aeromedical operators, who continuously monitor the pilots through video surveillance that records the pilots’ real-time images. Based on the responses of the trainees, the training intensity can be adjusted to optimize performance while minimizing the risk of G-LOC. Ideally, training should be halted as soon as symptoms of G-LOC are identified, such as lack of eye contact, increased facial stress, or mild muscle tension in the face. AOs issued a medical stop order when early signs were detected, halting the centrifuge from continuing to exert acceleration. However, G-LOC often develops subtly and may occur before any obvious symptoms become apparent. The rapid progression and transient nature of these early signs make it exceptionally challenging for aeromedical operators (AOs) to detect and interpret them in real time, even with extensive experience.

Owing to enhanced signal-to-noise ratio and information transfer rate, brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and electroencephalogram (EEG) technology have been increasingly applied in neural state monitoring in recent years [

1]. Recent studies have employed machine learning to analyze biosensor data for objectively assessing an individual’s state in PTSD, moving beyond traditional self-reporting methods [

2]. Similar to this approach, G-LOC research leverages biosensor data to detect pre-syncopal autonomic nervous system instability, providing a parallel for using physiological markers rather than self-reports for objective diagnosis. In an effort to reduce reliance on subjective human judgment among aeromedical operators, researchers have explored the use of machine learning techniques to predict G-LOC. Current methods for G-LOC prediction often depend on sensor-based equipment, such as EEG [

3,

4], electromyography (EMG) [

5], and eye tracking devices [

6]. Notably, pupil diameter and EEG features, particularly the power measured at the parietal site, were identified as critical indicators for the early detection of G-LOC [

7]. Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of combining physiological indicators with physical manifestations to assess a pilot’s precursor state of consciousness. Despite these advancements, current methods often rely on sensor-based equipment, which can interfere with training and limit practicality [

8]. Despite the performance advantages of deep learning algorithms, their deployment on mobile and wearable devices faces challenges due to limited computational power, memory capacity, and battery life, which restrict the local execution of complex models. Moreover, the reliance on multiple sensors increases operational complexity and cost, limiting the scalability of these solutions [

9].

The inherent challenges in detecting early signs of G-LOC during high-G training highlight the need for more nuanced physiological monitoring systems. While AOs traditionally rely on observable symptoms like facial tension or loss of eye contact, these indicators often appear too late to prevent an impending loss of consciousness. This is where Facial Action Coding System (FACS) AU-based micro-expression analysis can play a transformative role [

10]. By focusing on subtle, involuntary facial muscle movements that precede overt symptoms, AU analysis provides a more granular and objective assessment of a pilot’s physiological state.

Microexpressions captured through AU coding, such as brow furrowing or eyelid tightening, can serve as early biomarkers of cerebral hypoxia long before conscious impairment becomes apparent. These micro-level facial actions are difficult for human observers to consistently detect in real time due to their fleeting nature, but computer vision algorithms trained in AU recognition can identify these patterns with high precision. When integrated with existing monitoring systems, AU analysis could enable earlier intervention by correlating specific facial action units with declining cognitive function.

The application of AU analysis in this context represents a shift from reactive to predictive monitoring. By detecting the earliest physiological precursors to G-LOC often before the pilot is even aware of them, this technology could provide critical extra seconds for preventive measures. As high-performance aviation continues to push physiological limits, such advanced biometric monitoring may become indispensable for maintaining pilot safety during extreme maneuvers. The integration of AU-based systems with traditional aeromedical oversight could significantly reduce G-LOC-related risks while optimizing high-G training protocols.

To address these limitations, we propose an innovative, image-based method for real-time G-LOC prediction during HPHC training. Unlike existing sensor-based approaches, we propose a novel Vision Transformer (ViT) framework for AU feature extraction. The core innovation lies in its visual–semantic collaborative modeling architecture, which effectively integrates convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with vision Transformers. Specifically, the framework employs ResNet at the bottom layer to process image sequences, capturing spatiotemporal dynamics of facial microexpressions. Leveraging the long-range interaction capabilities of self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms in Transformers, we introduce a semantic-embedded label query network and an instance-conditioned code language model. The label query network adopts an encoder-decoder structure, where each AU label is represented as a learnable query.

Furthermore, we develop a graph convolutional hybrid network tailored for G-LOC prediction. This network innovatively combines graph convolution with physiological prior knowledge to construct an AU correlation graph. By incorporating a dynamic graph learning mechanism, the model adaptively adjusts inter-AU relationship strengths while preserving physiological plausibility.

To address these problems and build upon previous experiences, a new method for G-LOC detection based on facial action units is proposed. The main contributions are as follows:

We introduce a pioneering non-invasive, sensor-free G-LOC prediction system leveraging AUs as physiological biomarkers. In contrast to traditional methods requiring physical attachments, our framework relies uniquely on RGB cameras to capture subtle microexpressions related to AU linked to cerebral hypoxia.

We propose a novel vision–semantics collaborative Transformer for AU feature extraction, combining spatiotemporal modeling with the attention mechanisms of Transformers. By encoding each AU label as a learnable query, which dynamically interacts with visual features via cross-attention, our approach achieves precise AU recognition even under high-stress conditions.

We propose a novel GC-ViT framework for G-LOC detection through AU analysis. The model incorporates motivated graph structures where nodes represent key AUs and edges capture their dynamic interactions during G-LOC. Evaluated on centrifuge training data, the framework achieves strong performance with an AUC-ROC of 0.898 and an AP of 0.96.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on AU detection and the application of GCNs in AU recognition.

Section 3 introduces system implementation and hardware architecture.

Section 4 introduces the proposed GC-ViT architecture, designed for accurate recognition of G-LOC-related facial movements.

Section 5 validates the effectiveness of the proposed system through ablation studies and generalization experiments. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the overall work and provides a comprehensive conclusion regarding the model’s performance.

3. System Implementation and Hardware Architecture

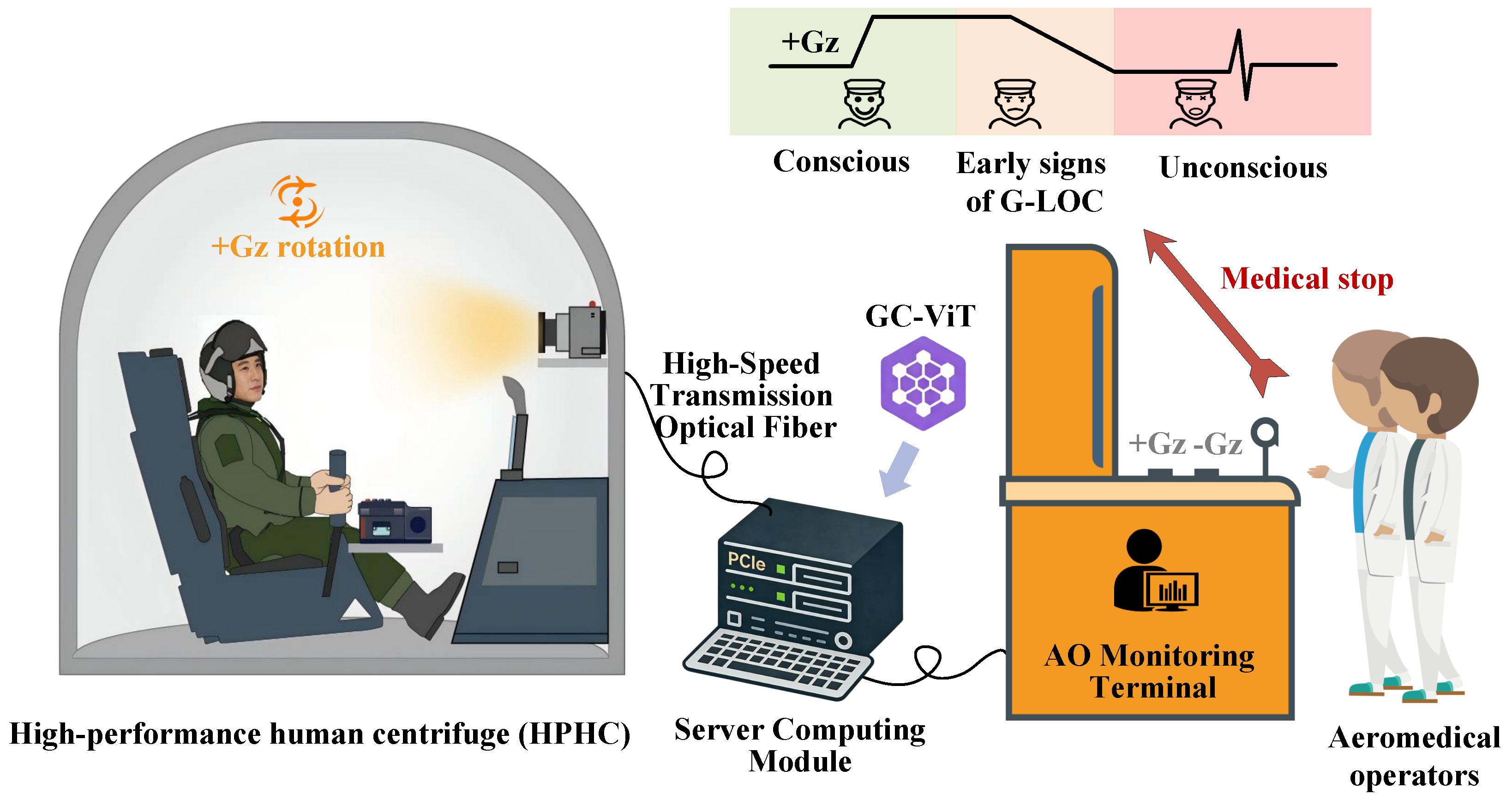

To transform the GC-ViT algorithm from theoretical research into a practically applicable aeromedical monitoring tool, this study designs a modular hardware architecture that requires no modifications to existing HPHC, enabling direct integrated deployment. As illustrated in

Figure 1, this architecture is composed of four core modules—image acquisition, high-speed transmission, server computing, and AO monitoring terminal—and establishes a complete technical closed-loop of “acquisition-transmission-computation-feedback”.

Among these modules, the image acquisition module adopts an industrial-grade RGB high-definition camera, deployed directly in front of the pilot inside the HPHC cabin. Operating at 30 fps, it captures facial images while supporting real-time facial Region of Interest (ROI) cropping and preprocessing. The camera is adaptable to the complex lighting conditions of the training cabin, ensuring the accuracy of subsequent AU feature extraction. The captured image data is efficiently transmitted via a high-speed transmission optical fiber module, which features a transmission rate of no less than 10 Gbps and latency controlled within 5 ms. Equipped with strong anti-electromagnetic interference capabilities, the module effectively avoids data loss and out-of-sequence issues through optimized transmission protocols, guaranteeing the integrity of image sequences.

As the core processing unit of the system, the server computing module is equipped with dual NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPUs, Peripheral Component Interconnect Express (PCIe) 4.0 interfaces, and high-speed storage devices, enabling it to efficiently meet the real-time computing requirements of the GC-ViT algorithm. Meanwhile, the AO monitoring terminal can real-time display the pilot’s facial video, AU feature heatmaps, and G-LOC risk probability. It also supports historical data retrieval and emergency stop triggering functions, providing intuitive decision support for aeromedical operators.

The data processing of the entire system follows a closed-loop logic: after the camera captures and preprocesses facial images, the high-speed optical fiber module transmits the data to the server in real time. The server, with the pre-deployed GC-ViT algorithm, sequentially completes AU feature extraction and G-LOC state judgment. The AO monitoring terminal synchronously receives and displays the analysis results, automatically triggering an early warning when an abnormal state is detected. This facilitates timely intervention by the AOs, which can directly execute a medical stop operation to ensure training safety.

4. Methodology

4.1. Model Architecture Overview

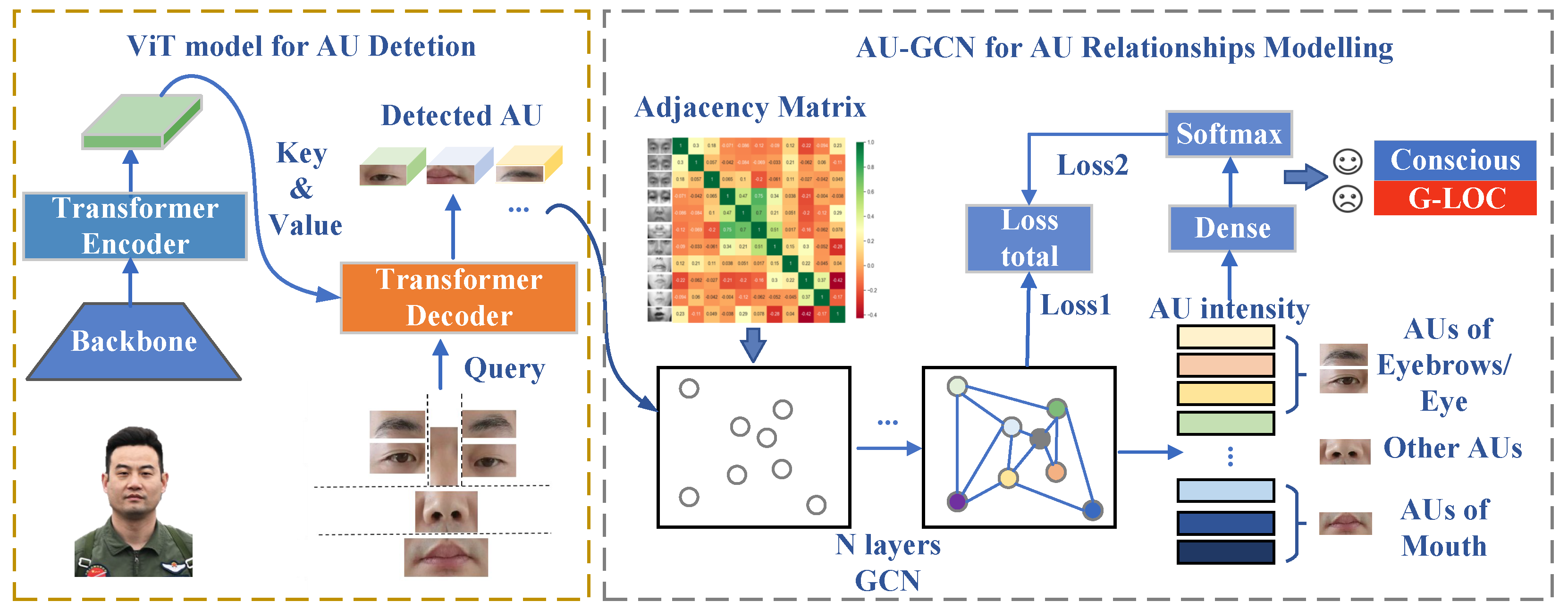

This study presents an enhanced Transformer-based architecture for AU detection, designed to capture subtle facial expressions in HPHC training scenarios. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the proposed GC-ViT architecture adopts an encoder-decoder framework with multi-stage feature extraction and semantic-guided attention mechanisms to achieve precise recognition of G-LOC-related facial movements.

To further exploit inter-dependencies among AUs, we incorporate GCN-based relationship modeling within the GC-ViT framework. The GCN module utilizes the initially detected AU probabilities as node features, while incorporating established AU correlations as prior knowledge for graph construction. Through stacked graph convolution operations performed on this relational graph, the model produces updated feature representations that reflect learned AU interdependencies. These enhanced features are subsequently utilized for the final classification task of determining pilot consciousness states.

As shown in the GC-ViT Architecture, the proposed system systematically integrates visual feature extraction, semantic-visual interaction, and structured AU relationship modeling to enhance the detection of G-LOC in HPHC training scenarios. The refined AU representations, enriched by graph-based dependency learning, serve as discriminative features for assessing the pilot’s G-LOC state. By capturing subtle facial movements and their interdependencies, our GC-ViT Architecture provides a robust framework for real-time consciousness monitoring under high-G conditions.

4.2. ViT for AU Detetion

The encoder module employs a ResNet-50 backbone network to extract hierarchical visual features from the input image . Through five convolutional blocks, the network generates a feature map with spatial dimensions and , where denotes the channel depth. To adapt these features for Transformer-based processing, a convolutional layer reduces the channel dimension to , yielding . The spatial features are then flattened into a sequence representation , where corresponds to the number of spatial positions.

For positional encoding, we implement learnable 2D position embeddings that preserve spatial structure while avoiding potential inductive biases associated with traditional sinusoidal encoding:

where

contains learnable positional parameters. This approach maintains critical spatial relationships between facial regions while allowing flexible adaptation to varying input resolutions.

The encoder’s primary function is to enhance visual features corresponding to key facial regions including eyelids, eyebrows, and perioral areas that exhibit characteristic muscle movement patterns during G-LOC episodes. Through hierarchical feature extraction and spatial encoding, the encoder captures both: Local muscle activation patterns. The encoded features thus contain rich, position-aware representations of facial dynamics essential for subsequent AU-specific decoding. The encoder architecture effectively transforms raw pixel data into a structured, high-level representation suitable for analyzing subtle neuromuscular changes characteristic of G-LOC progression. Subsequent cross-attention mechanisms in the decoder can then focus on clinically relevant spatial-temporal patterns within this optimized feature space.

The decoder module employs a set of C learnable AU query vectors denoted as

, where each query vector

encapsulates the semantic representation of a specific AU (e.g.,

encodes “AU01 = inner brow raiser”). These query vectors interact with the encoded visual features

through a cross-attention mechanism, formally expressed as:

Here,

denotes the baseline ocular region embedding and

represents a learnable displacement vector. The model further employs multi-head attention (with 8 parallel attention heads) to capture heterogeneous feature subspace relationships, where each attention head computes:

This equation computes the h-th attention head’s output in a multi-head attention layer. Here, , , and are the query, key, and value matrices for head h, while d is the feature dimension and H is the number of attention heads. The scaled dot-product attention first measures similarity between queries and keys, then applies softmax to get attention weights, which are used to weight the values.

This section presents a Transformer-based framework for AU feature extraction. The model employs learnable AU query vectors to enhance visual feature encoding through self-attention mechanisms in the encoder module. Subsequently, cross-attention operations are applied to extract AU-specific semantic representations from the encoded visual features. The incorporation of multi-head attention further enables the model to capture heterogeneous interactions across different feature subspaces, thereby strengthening its discriminative capacity for G-LOC-relevant micro-expression AUs.

4.3. GCN for AU Relationships Modelling

AUs are controlled by facial muscles and constrained by facial anatomy, resulting in inherent relationships between their intensities. During anti-G straining maneuvers under high-G conditions, pilots activate specific AUs. To assess training effectiveness, this study develops an intensity correlation model to capture the interactions between different AUs. Co-occurrence relationships arise when certain AUs are frequently activated together due to muscle interactions, such as cheek raising and lip corner pulling. Conversely, mutual exclusion relationships describe AUs that rarely co-occur, such as brow lowering and lip corner stretching in natural expressions. The structural dependencies among AUs influence not just their activation but also their intensity relationships. For instance, AU01 (inner brow raiser) and AU02 (outer brow raiser), both controlled by the muscle, typically activate together with correlated intensities. The Pearson correlation coefficient

is calculated as:

where

Y denotes facial action unit indices,

and

are the standard deviation and mean of sample

X, respectively. The Pearson correlation coefficient is derived from the covariance divided by the product of standard deviations.

The coefficient ranges from −1 to 1. Values approaching 1 indicate strong co-activation relationships, while values near −1 suggest mutual exclusion. A coefficient of 0 implies no linear relationship between AU intensities. Based on centrifuge training video data of pilots performing anti-G straining maneuvers, we computed a heatmap of Pearson correlation coefficients to visualize these inter-AU relationships. This quantitative analysis enables objective evaluation of G-force respiratory training effectiveness through facial muscle activation patterns.

The inputs

,

, …,

are fed into the graph convolutional network of the facial action unit learning module. Through learning in the two-layer graph convolutional network, the outputs

,

, …,

are obtained. The formula for the graph convolutional network is as shown in:

Here, represents the output of the graph convolutional network, i.e., , , …, . represents the input of the graph convolutional network, i.e., , , …, . denotes the adjacency matrix, which is a dependency matrix derived from statistical analysis of facial action unit dependencies in the dataset. and are the parameters of the graph convolutional network, and Relu represents the activation function.

The 12 × 1 AU feature vector learned through graph convolutional networks is fed into a fully connected layer for feature transformation. This dense layer linearly maps the 12 dimensional AU feature space to a 2-dimensional space, corresponding to the binary classification task of determining whether a pilot experiences G-LOC. The output of the fully connected layer represents unnormalized class scores. These logits are then processed by a softmax layer for probability normalization. The softmax function applies exponential transformation and normalization to the logits, ensuring that the sum of the two output class probabilities strictly equals 1, thereby generating precise probabilistic estimates of G-LOC occurrence.

The GCN of the AU learning module further incorporates a dynamic graph modeling mechanism to adapt to the time-varying characteristics of AU interaction patterns during high-G training. Its core lies in designing dynamic update logic based on the phased features of the G-LOC training process—unlike update methods driven by video frame sampling frequency, this study treats 20 consecutively extracted AU-specific semantic representations (each containing 12-dimensional AU intensity features, anatomical weight features, and timestamp information) as a dynamic update unit. That is, the adjacency matrix weights are dynamically adjusted once per input batch of AU semantic sequences (corresponding to a continuous action phase in G-LOC training, such as the anti-G force maintenance phase or overload increment adaptation phase). This design not only aligns with the non-instantaneous characteristics of facial muscle responses under high-G overload (the evolution of muscle synergy patterns requires a certain time window to manifest) but also avoids noise accumulation caused by frame-by-frame updates, ensuring the model focuses on physiologically meaningful trends in AU association evolution.

The construction of the dynamic adjacency matrix integrates a hierarchical strategy of anatomical prior initialization, data-driven weight update, and adaptive sparsification filtering: First, constrained by facial muscle anatomical associations (e.g., frontalis muscle synergy for

-

, zygomaticus muscle linkage for

-

), an initial adjacency matrix

is constructed by combining the Pearson correlation coefficients of AU intensities in the training set. The element

is defined as the weighted fusion of the anatomical association weight

and statistical correlation coefficient

between

and

:

where

denotes the fusion coefficient (set to

via 5-fold cross-validation to balance anatomical priors and data statistical features). Subsequently, for each input batch of AU semantic representation sequences

, the dynamic association strength

between AUs within the current batch is calculated, which fuses cosine similarity in the feature space and mutual information in the time series to capture spatiotemporal correlations:

where

represents the cosine similarity of AU feature vectors, and

denotes the mutual information of the intensity sequences of

and

(

indicates the probability distribution). The adjacency matrix weights are then updated as follows:

where

is the Sigmoid function (utilized to normalize the association strength to the interval

). Finally, top-

K sparsification filtering is implemented not by predefining a fixed range for

K, but by adaptively determining

K based on the feature discriminability criterion of each AU node in the current batch

, where lower entropy indicates more focused node associations. Experimental validation across multiple groups demonstrates that when retaining the top-

K connections for each AU node by association strength, the node discriminability entropy reaches a minimum at

; thus,

is ultimately determined. The filtered adjacency matrix

satisfies:

where

denotes the set of the top three AU nodes with the strongest association to

. The calculation of dynamic graph convolution remains based on the original framework, but the adjacency matrix is replaced with the real-time updated sparsified matrix

:

This design enables the model to dynamically capture synergistic and antagonistic relationships between AUs throughout the G-LOC training process, avoiding the over-smoothing problem caused by fully connected graph structures while anchoring key physiological associations through the combination of anatomical priors and data-driven learning. This provides more discriminative feature representations for the subsequent G-LOC binary classification task.

4.4. Loss Function for the Model

The complete loss function consists of two components: AU detection loss and graph-based G-LOC state prediction loss. The first component measures the discrepancy between predicted AU intensities and ground truth labels using visual Transformer features:

where

represents the continuous ground-truth intensity of facial action units,

denotes the visual Transformer’s output features for the

i-th sample, and

is the sigmoid activation function.

The second component

represents the graph classification loss for G-LOC state prediction, computed using the predicted AU vectors as input features:

where

indicates the true G-LOC state (0 for non-G-LOC, 1 for G-LOC), and

is the predicted probability of G-LOC state derived from graph neural network processing of AU features.

The total loss combines both components with balancing coefficients:

where

controls the relative importance between AU detection and G-LOC state prediction tasks. This multi-task learning framework enables joint optimization of facial action unit recognition and G-LOC state classification through feature sharing between the visual Transformer and graph neural network.

5. Discussion

5.1. Dataset Processing and Model Training

The DISFA dataset [

19] consists of video recordings from 27 participants (12 females and 15 males), containing over 100,000 annotated frames. Each frame is annotated with intensity scores ranging from 0 to 5 for 12 AUs. Following the experimental protocols established in [

20,

21], we conduct subject-exclusive 3-fold cross-validation on all 12 AUs (AU01, AU02, AU04, AU05, AU06, AU09, AU12, AU15, AU17, AU20, AU25, AU26, etc.). For binary classification, samples with intensity ≥2 are designated as positive instances, while others are considered negative.

Our own dataset comprises 40 real-world videos capturing 32 pilots undergoing centrifuge training, during which G-LOC incidents were recorded. These videos, acquired at 30 fps, yielded a total of 15,000 frames, with 10% randomly selected for evaluation in the test set. Both datasets were constructed following standardized protocols to ensure data consistency and reliability. Notably, the limited dataset size is primarily due to the inherent challenges in acquiring G-LOC-related data: First, G-LOC may cause potential irreversible damage to pilots’ nervous and cardiovascular systems, so aeromedical operators closely monitor pilots in real-time during high-G centrifuge training and immediately halt sessions upon detecting early precursors, resulting in very few recordable valid cases. Second, even suspected G-LOC incidents require rigorous screening of raw video data—only frames with clear facial regions, recognizable action units, and correspondence to G-LOC precursor phases are retained, leading to 15,000 valid frames (far fewer than the original recording volume). This constrains the model’s generalization ability, as the small dataset cannot fully cover individual heterogeneities among pilots, potentially reducing adaptability to unseen samples. Nevertheless, the model has achieved reliable performance on the current dataset, validating its core effectiveness. In future work, we will expand the dataset with more diverse pilots (across age, flight experience, and physiological status) to further enhance generalization and robustness.

The experimental framework was implemented using PyTorch, a widely adopted deep learning platform. To accelerate model training, we utilized a high-performance computing system equipped with dual NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPUs, each featuring 32 GB of video memory.

5.2. Analysis of Backbone Architectures for ViT Models

In this ablation study, we systematically investigate the impact of different backbone networks on the performance of ViT models. To comprehensively evaluate the feature extraction capabilities, computational efficiency, and real-time applicability of backbone networks, we selected five representative architectures for comparison: ResNet50, DenseNet169, MobileNetV3, VGG-16, and EfficientNetB0. As shown in

Table 1, these networks exhibit distinct performance characteristics in terms of accuracy, computational overhead, and inference speed in our experiments. ResNet50, as a classical residual network, offers excellent feature extraction capability and training stability but incurs considerable computational costs. DenseNet169 achieves feature reuse through dense connections, theoretically enhancing feature propagation efficiency yet introducing higher latency. MobileNetV3 employs lightweight designs like depthwise separable convolutions, making it suitable for examining the trade-off between computational efficiency and model performance. VGG-16, as an early deep network, helps analyze the impact of network depth on feature extraction through its simple stacked structure but suffers from significant parameter redundancy and inefficient computation. EfficientNetB0 represents the state-of-the-art compound scaled network, validating how advanced network designs can enhance Transformer performance while maintaining computational efficiency.

The experimental results demonstrate that different backbone networks significantly impact Transformer model performance, computational overhead, and real-time responsiveness. ResNet50 and DenseNet169 achieve a good balance between accuracy and computational cost, with DenseNet169 particularly excelling in few-shot learning tasks due to its dense connection properties. However, ResNet50—consistent with literature observations—exhibits high computational intensity, which would hinder real-time early warning for time-critical onboard systems. Notably, EfficientNetB0 achieves the best accuracy among all compared models (Val AUC = 0.934, Val F1 = 0.819) while maintaining the lowest computational overhead: its inference time (47 ms) is only 42% of ResNet50 and 24% of VGG16, and its peak memory usage (96 MB) is 54% of ResNet50, verifying the effectiveness of compound scaling strategy in feature extraction and efficiency balancing. VGG-16 performs relatively poorly, which relates to its shallower feature extraction capability and significant parameter redundancy, further confirming the importance of modern network architecture design for reducing computational burden.

To further enhance the applicability of the GC-ViT architecture for onboard deployment, we implemented two targeted optimization strategies for the EfficientNetB0 backbone: INT8 post-training quantization and L1-norm based channel pruning. For INT8 quantization, we used TensorRT 8.4 to convert FP32 weights to INT8 with calibration on 10,000 representative frames from the centrifuge dataset, reducing memory bandwidth usage and accelerating computation without modifying the network structure. For channel pruning, we removed 40% of redundant channels in EfficientNetB0’s MBConv blocks and GCN layers (determined via 5-fold cross-validation to balance efficiency and accuracy), followed by 30 epochs of fine-tuning to recover minimal performance loss. As shown in

Table 2, the combined optimization achieves a 48.9% reduction in inference time (24 ms) and 53.1% reduction in peak memory usage (45 MB) compared to the original FP32 model, while maintaining high detection performance (Val AUC = 0.918, Val F1 = 0.805)—a negligible accuracy drop of only 1.71% that does not compromise G-LOC early warning reliability.

In summary, EfficientNet-B0 is the optimal backbone for ViT due to its exceptional balance of accuracy and efficiency. With only 0.39 G FLOPs and 5.3 M parameters, its compound scaling optimizes depth, width, and resolution synergistically, while MBConv blocks with depthwise convolutions and squeeze-excitation ensure robust feature extraction at minimal computational cost. To enhance the GC-ViT architecture’s suitability for onboard deployment, targeted optimization strategies—INT8 post-training quantization and 40% channel pruning—have been implemented and validated. These optimizations yield a 48.9% reduction in inference time (to 24 ms) and 53.1% reduction in peak memory usage (to 45 MB), with only a negligible 1.71% drop in Val AUC (to 0.918), ensuring the model retains robust G-LOC precursor detection capability while minimizing resource consumption. Complementing this efficiency, the optimized GC-ViT achieves an end-to-end latency of just 300 ms (0.3 s) for early warning, and alert signal generation—well within the 2–3 s window required for timely intervention in high-G scenarios.

5.3. Dynamic Correlation Characteristics, and Physiological Mechanisms of Key AU Pairs for G-LOC Prediction

While existing studies have explored the relevant characteristics of AUs, a critical research gap persists: the specific AU combinations that are most indicative of impending G-LOC have not been thoroughly identified, nor have their underlying physiological mechanisms been fully elaborated. The core objective of this study is to clarify which AU pairs can most reliably predict the onset of G-LOC. Accordingly, this section first identifies core AU combinations through a rigorous screening process, then systematically analyzes their dynamic correlation patterns during the G-LOC prodromal period, and ultimately reveals the physiological basis of these patterns by integrating aerospace physiology principles. This work aims to enhance the scientific insights of the research and provide practical biological markers for the early warning of G-LOC.

Based on the FACS standards and aerospace medicine research consensus, 12 core AUs related to hypoxic stress, respiratory compensation, and facial muscle coordination were selected as the research objects (AU01, AU02, AU04, AU05, AU06, AU09, AU12, AU15, AU17, AU20, AU25, AU26). All possible AU pair combinations were first generated, totaling 66 pairs. Subsequently, a two-step screening method (“data pre-screening + physiological validation”) was adopted to identify core combinations with research value.

In the data pre-screening phase, the correlation characteristics of AU intensities in the normal group (no G-LOC risk, acceleration ) were used as the criterion. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (r) was employed to quantify the linear correlation strength of AU pairs, and only those with Pearson in the normal group were retained. This step excluded “inherently strongly correlated” combinations, which exhibit tight correlations even in normal states and thus cannot reflect dynamically enhanced correlations induced by G-LOC.

In the physiological validation phase, based on anatomical principles and referring to the corresponding relationships between AUs and controlling muscles in FACS standards, only AU pairs controlled by the same muscle or synergistic muscles were retained. Specifically, three types of synergistic relationships were considered: (1) Control by different branches of the same muscle (e.g., the medial and lateral branches of the frontalis muscle control AU01 and AU02, respectively); (2) Control by functionally synergistic muscles (e.g., the orbicularis oculi muscle and zygomaticus major muscle control AU06 and AU12, respectively, which synergistically participate in stress responses and respiratory assistance); (3) Control by functionally associated muscles (e.g., the zygomaticus major muscle and orbicularis oris muscle control AU12 and AU25, respectively, which jointly participate in respiratory compensation during hypoxia).

Through the above screening process, five core AU pairs were finally identified: AU06-AU12, AU01-AU02, AU12-AU25, AU06-AU05, and AU04-AU15. These combinations not only meet the data analysis requirement of “weak correlation in normal states” but also have clear anatomical synergistic foundations. Moreover, they are frequently studied AU combinations in FACS research and aerospace medicine, providing reliable objects for subsequent dynamic correlation analysis and physiological mechanism interpretation.

To accurately capture the changing patterns of AU pair correlation strength as G-LOC approaches, the G-LOC prodromal period was divided into two key time windows: the early prodromal period (, 3–6 s before loss of consciousness) and the immediate prodromal period (, 0–3 s before loss of consciousness), with the normal group (C) as the control. The Pearson correlation coefficient mean (M) ± standard deviation () was used to quantify the linear correlation strength of AU pairs in each window, and the trend -value (slope) and t-test were employed to verify the significance of the increasing trend in correlation strength.

As shown in

Table 3, the correlation strength of all five core AU pairs exhibits an extremely significant linear increase as G-LOC approaches (all

t-values correspond to

,

), confirming that the synergistic interactions between specific AUs are closely associated with the physiological progression of G-LOC. Among these pairs, AU06 (eye closure)-AU12 (lip corner pulling) shows the most prominent increasing trend: the correlation strength is only

in the normal group, rises to

in

, and reaches

in

(

), making it the most sensitive to G-LOC-related physiological changes. AU01 (inner brow raiser)-AU02 (outer brow raiser) follows, with the correlation strength gradually increasing from

to

(

), reflecting the enhanced synergistic activation of the frontalis muscle branches. AU12-AU25 (lip corner pulling-lips parting), AU06-AU05 (eye closure-upper lid lowering), and AU04-AU15 (brow lowering-lip corner depression) all show weak correlations in the normal group (

to

), increase to

to

in

, and further rise to

to

in

(

to

). Notably, the correlation strength of all core AU pairs in

(3–6 s before loss of consciousness) has reached 1.5–2.0 times that of the normal group, providing a critical time window for the early warning of G-LOC.

The enhanced correlation of core AU pairs is not an accidental data association but an external manifestation of physiological stress responses induced by cerebral hypoxia before G-LOC, which is highly consistent with the human physiological regulation mechanisms under high-G loads. The synergistic activation of AU06-AU12 is the most indicative: when oxygen supply to the retina is insufficient, the orbicularis oculi muscle controls the contraction of AU06 to focus vision, while the zygomaticus major muscle regulates AU12 to assist respiratory muscle exertion. This pair corresponds to the core process of “hypoxia-visual compensation-respiratory regulation,” resulting in the most significant increase in correlation. AU01-AU02 is controlled by the branches of the frontalis muscle; cerebral hypoxia induced by high-G loads activates the sympathetic nervous system, triggering the body’s inherent stress response. The contraction of the frontalis muscle leads to brow raising, which is associated with hypoxia-induced anxiety and serves as a typical manifestation of physiological discomfort, with the enhanced correlation reflecting the intensification of stress. AU12-AU25 focuses on the respiratory compensation mechanism: the relaxation of the orbicularis oris muscle enables AU25 (lips parting) to expand the airway cross-sectional area, and its synergy with the contraction of the zygomaticus major muscle (controlling AU12) optimizes respiratory efficiency, with the increased correlation reflecting the deepening of hypoxia and enhanced compensation. The synergistic activation of the eye-related pair AU06-AU05 is closely linked to hypoxia-induced visual dysfunction; both AUs are controlled by the synergistic action of the orbicularis oculi muscle and levator palpebrae superioris muscle. When hypoxia reduces visual sensitivity, their contraction regulates eyelid opening to reduce ineffective light stimulation, and the enhanced correlation objectively reflects the strengthened ocular compensatory response. The synergistic activation of AU04-AU15 is mainly related to hypoxia-induced stress and discomfort: AU04 is controlled by the corrugator supercilii muscle, and AU15 by the depressor anguli oris muscle. Their synergistic contraction not only reflects the pilot’s subjective feeling of discomfort but also embodies the excitatory response of the central nervous system under hypoxia, with the increasing correlation further confirming the abnormal physiological changes before G-LOC.

5.4. AU-GCN Performance in G-LOC State Classification

5.4.1. Context-Aware Fused Dynamic Graph Enhances Facial AU Clustering: t-SNE Analysis

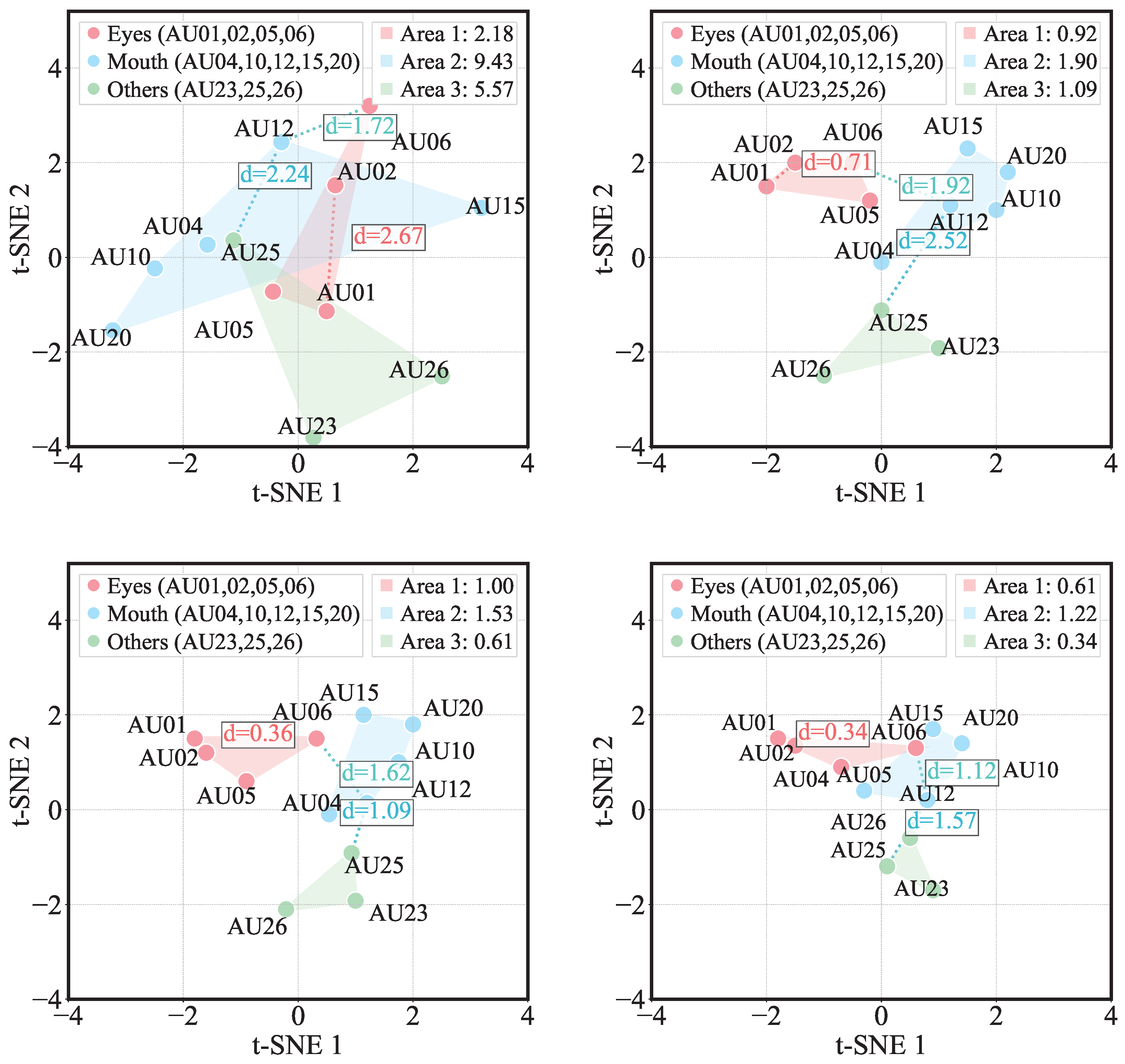

To validate the architectural design of AU-GCN, we conducted systematic ablation studies by comparing its performance against traditional MLP baselines (which lack explicit modeling of AU dependencies) and evaluating three graph initialization strategies (fixed correlation-based, fully connected, and identity matrix), while further introducing an optimized dynamic graph variant that fuses biologically inspired AU prior correlations with G-LOC context-aware adjacency matrices. This comprehensive experimental design aimed to assess whether integrating data-driven relational priors, physiological knowledge, and scenario-specific constraints could outperform rigid static graph or unstructured MLP/CNN feature processing approaches, with t-SNE visualizations and convex hull area quantifications providing intuitive and quantitative insights into AU clustering performance across different models.

In

Figure 3, the top-left corresponds to the MLP baseline, which exhibits severe convex hull overlap among three predefined AU groups—Eyes (AU01, 02, 05, 06), Mouth (AU10, 12, 15, 23, 26), and Others (AU04, 20, 25)—accompanied by excessively large convex hull areas (Eyes: 2.18, Mouth: 9.43, Others: 5.57). This dispersion confirms that MLPs treat AUs as isolated features, lacking the capacity to model either anatomical groupings (e.g., co-activated eyebrow-eye muscles) or G-LOC contextual associations. Notably, the Mouth group—comprising physiologically synergistic actions was the most scattered, highlighting traditional neural networks’ inherent inability to leverage natural facial muscle coordination patterns. In contrast, the top-right denotes the fixed-adjacency GCN initialized via Pearson correlations, which demonstrates significant improvements in clustering compactness with drastically reduced convex hull areas (Eyes: 0.92, Mouth: 1.90, Others: 1.09). This validates that static graph structures encoding biologically plausible AU relationships (e.g., AU01-AU02 co-activation in eyebrow movement) effectively constrain feature learning toward anatomically meaningful groupings. However, the static nature of the adjacency matrix introduces inherent limitations: it cannot adapt to dynamic interactions such as the coordination between AU06 (eye closure) and AU12 (lip corner raising) in G-LOC scenarios, revealing a critical trade-off between prior knowledge encoding and dynamic adaptability.

The bottom-left represents the vanilla dynamic graph model, which further compresses intra-group dispersion through adaptive edge updates, achieving convex hull areas of Eyes: 1.00, Mouth: 1.53, and Others: 0.61. It selectively strengthens physiologically meaningful connections while suppressing spurious correlations, enabling superior isolation of infrequent AUs in the “Others” group. Nevertheless, its reliance solely on data-driven dynamic learning occasionally overlooks stable anatomical priors, leading to marginal compromises in the clustering consistency of core AU pairs. More importantly, the bottom-right corresponds to the optimized dynamic graph fusing AU biological priors with G-LOC context-aware adjacency matrices, which achieves the optimal clustering performance. It exhibits the smallest and most compact convex hull areas across all groups (Eyes: 0.61, Mouth: 1.22, Others: 0.34) with non-overlapping convex hulls. This breakthrough stems from its dual mechanism: leveraging physiological priors to preserve stable anatomical synergies and integrating G-LOC scenario constraints to adaptively model dynamic, context-dependent interactions (e.g., AU06-AU12 coordination during impending consciousness loss).

Collectively, these findings underscore the critical role of structured graph modeling in capturing facial AU synergies, as unstructured MLP and locally constrained CNN approaches fail to model non-local dependencies and anatomical groupings. The optimized AU-GCN architecture, in particular, achieves structured clustering aligned with human facial anatomy, dynamic adaptability to scenario-specific AU interactions, and efficient noise suppression that avoids the over-smoothing of fully connected graphs and spurious correlations of vanilla dynamic graphs. By integrating biological priors and G-LOC context, this model effectively captures both stable anatomical dependencies and dynamic, non-local interactions, laying a critical foundation for accurate detection of impending loss of consciousness via facial muscle coordination patterns.

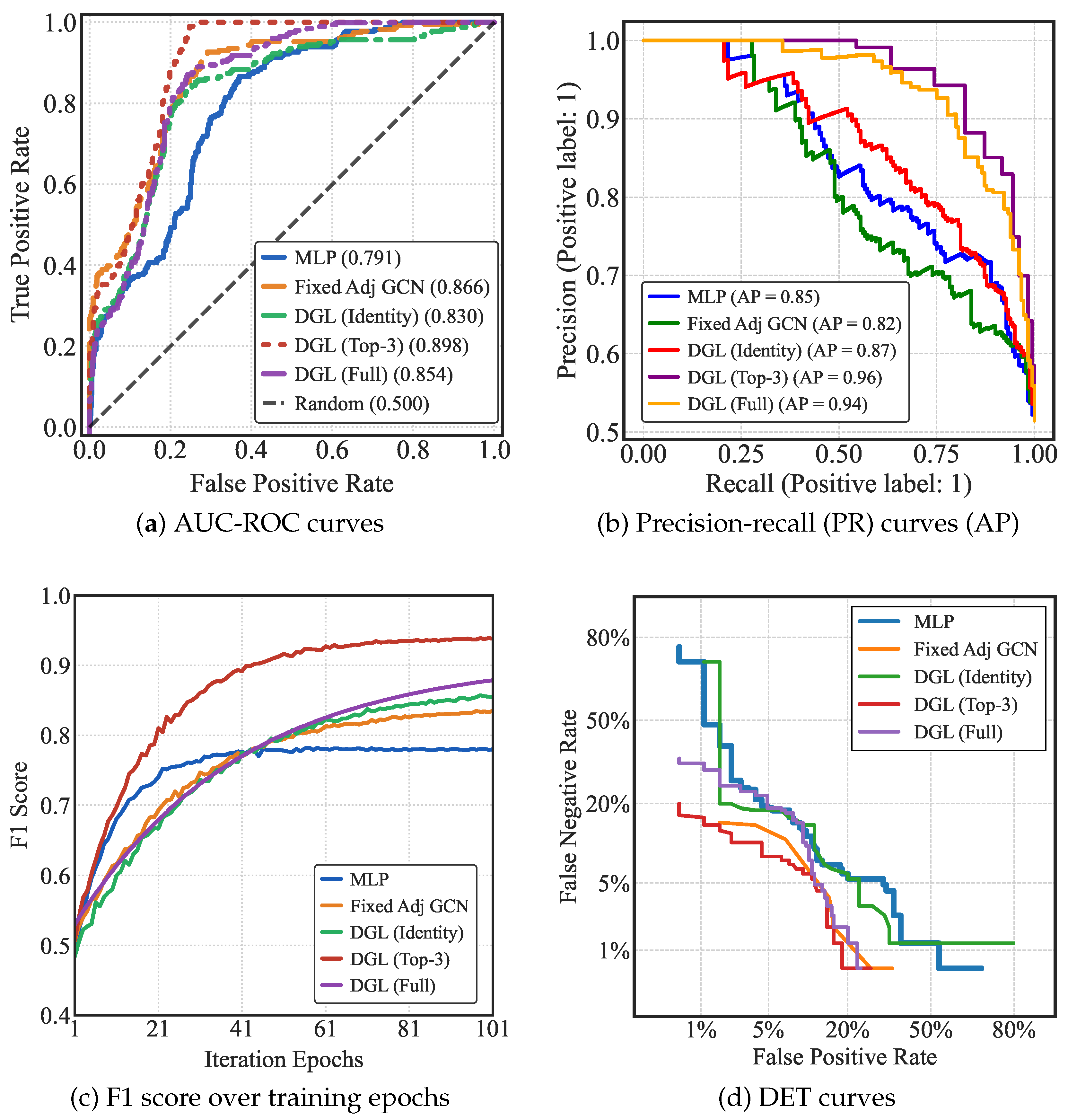

The comprehensive evaluation results illustrated in

Figure 4 (encompassing F1 Score, AUC-ROC, PR, and DET metrics) demonstrate substantial performance disparities among the five models MLP, Fixed Adj GCN, DGL (Identity), DGL (Top-3), and DGL (Full) across all evaluation dimensions, with graph-based models consistently outperforming the baseline MLP model. Notably, the dynamic Top-3 graph convolution model DGL (Top-3) achieves the most prominent performance across all metrics, supported by robust quantitative and qualitative evidence.

In terms of the AUC-ROC metric (

Figure 4 AUC-ROC panel), the DGL (Top-3) model achieves the highest AUC value of 0.898, with the random baseline serving as a reference. This indicates that graph-based models possess stronger capability in distinguishing critical action unit (AU) combinations associated with impending loss of consciousness from normal facial movements compared to the conventional MLP, and the dynamic Top-3 graph structure further optimizes this discriminative power.

The PR curve analysis (

Figure 4 PR panel) complements the AUC-ROC results by quantifying the model’s precision-recall trade-off, with the Average Precision (AP) serving as a key indicator. The DGL (Top-3) model attains an exceptional AP of 0.96, outperforming all other models. This high AP value robustly validates the model’s ability to accurately identify critical AU combinations while minimizing false positive predictions, which is crucial for distinguishing subtle transitional facial movements preceding loss of consciousness from irrelevant facial activities.

Regarding the F1 Score evolution with training iterations (

Figure 4 F1 Score panel), the DGL (Top-3) model exhibits remarkable convergence efficiency and superior final performance: it rapidly converges to a high F1 Score as the training epochs progress (from 1 to 101), maintaining a leading position among all models. In contrast, the DGL (Identity) model, which adopts the identity matrix as the adjacency matrix, suffers from excessively slow convergence, failing to reach the F1 Score level of DGL (Top-3) even after extensive training. The MLP, Fixed Adj GCN, and DGL (Full) models demonstrate intermediate convergence rates and final F1 Scores, all of which are lower than those of the DGL (Top-3) model, highlighting the advantage of the dynamic Top-3 graph construction strategy in accelerating model convergence and enhancing classification performance.

Furthermore, the DET curve (

Figure 4 DET panel) confirms the operational reliability of the DGL (Top-3) model. In practical scenarios where both false alarms (False Positive Rate) and missed detections (False Negative Rate) incur significant consequences, the DGL (Top-3) model exhibits the optimal DET curve, indicating superior balance between reducing false positives and avoiding missed detections compared to the other four models. This reliability is particularly critical for the detection of impending loss of consciousness, where operational robustness directly impacts clinical or safety outcomes.

Collectively, these results collectively indicate that the dynamic graph architecture effectively learns the transitional facial muscle coordination patterns that signal impending loss of consciousness, outperforming conventional approaches in detecting this specific physiological state.

5.4.2. Dynamic Graph Learning Improves AU Modeling for G-LOC Detection

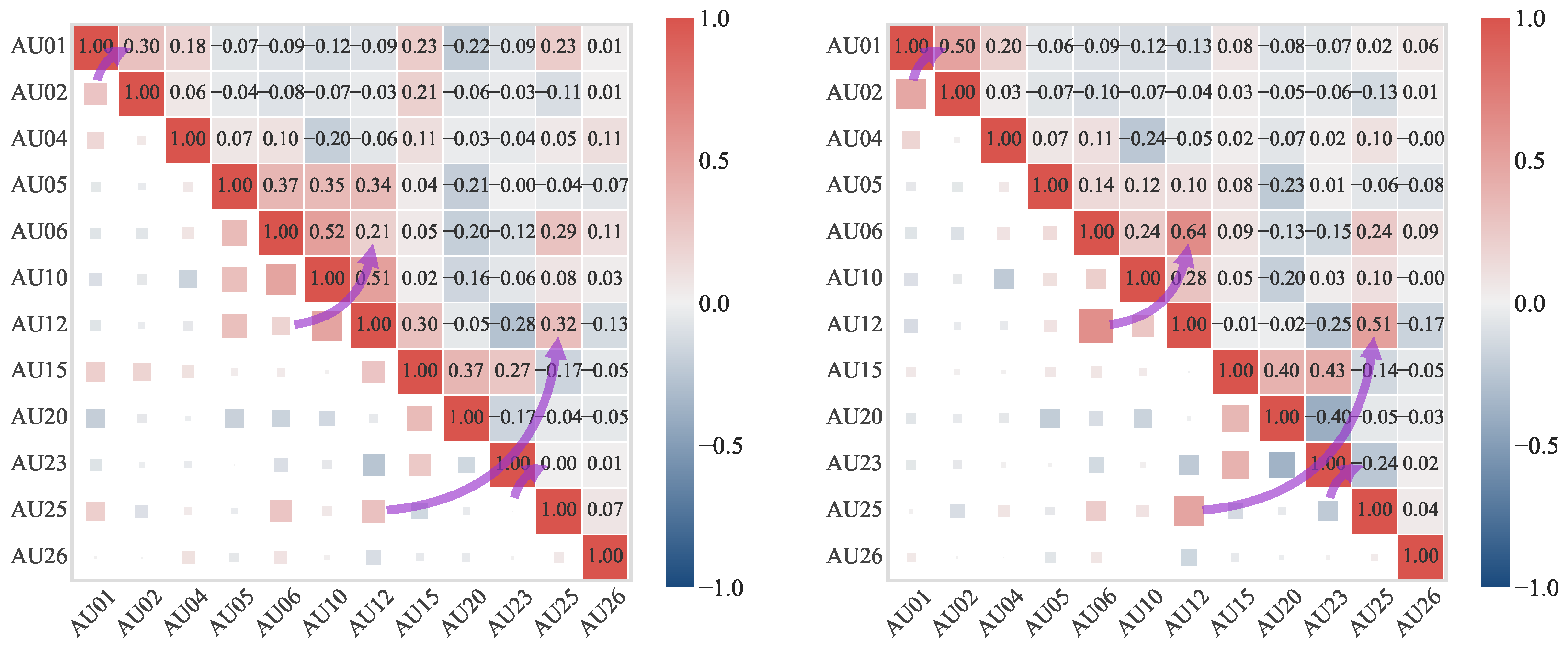

Through comparative analysis of AU relationship heatmaps, we examined the differences between fixed AU adjacency matrices and those generated by dynamic AU graph convolutional methods upon model convergence. The heatmaps visually represent the association strength between AU pairs through color coding (red for positive correlation/synergistic effects, blue for negative correlation/antagonistic effects) and grid size.

As shown in

Figure 5, the fixed AU adjacency matrix computed from the dataset highlights four key AU pairs (AU01-AU02, AU06-AU12, AU12-AU25, and AU23-AU25) with purple arrows. Based on prior knowledge in aerospace medicine, we focused on analyzing these key AU pairs relevant to pilots’ facial movements. In contrast, the

Figure 5 Right presents the learned AU adjacency matrix obtained via dynamic AU-GCN upon model convergence.

Experimental results demonstrate that while the fixed adjacency matrix precomputed from static datasets exhibits global positive correlations, it shows two notable limitations: the lack of significantly discriminative action unit combinations, and the inclusion of numerous weakly correlated relationships with low signal-to-noise ratios that may interfere with G-LOC state recognition. More importantly, its learnable adjacency matrix parameterization mechanism automatically achieves feature space sparsification, effectively suppressing interference from non-significant AU correlations while capturing nonlinear interaction patterns across varying G-load conditions through time-varying characteristics.

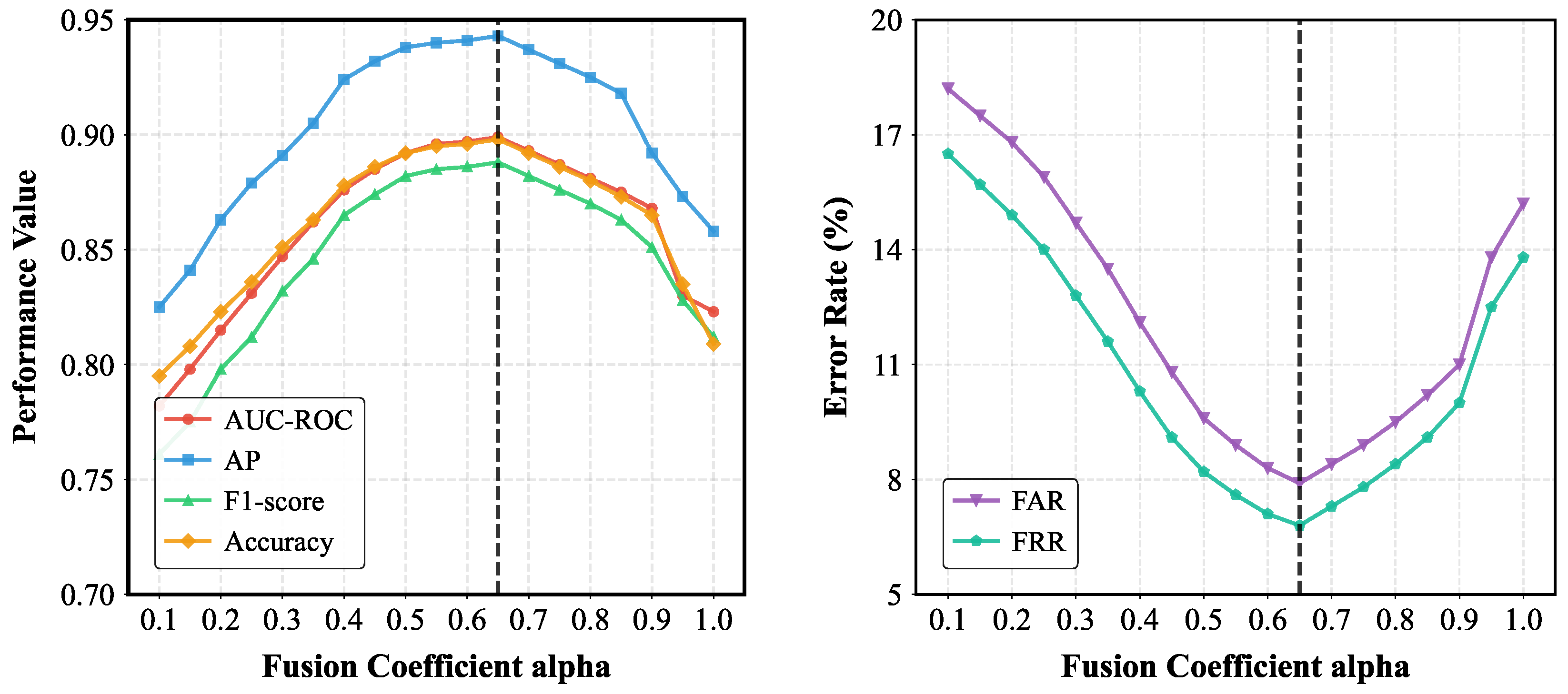

5.4.3. Nonlinear Impact of Fusion Coefficient on Model Performance

The fusion coefficient

mediates the balance between the adjacency matrix weight derived from the Pearson correlation coefficient

and the physiologically meaningful anatomical weight of facial muscles 1-

. As shown in

Figure 6,

varies from 0.1 to 1.0 with a step size of 0.05, the model’s classification performance metrics (AUC-ROC, AP, F1-score, Accuracy) and early warning reliability metrics (FAR, FRR) exhibit a consistent “rise-first-then-fall” nonlinear trend, fully revealing regulatory role in model performance. When

ranges from 0.1 to 0.65, all classification performance metrics show a steady upward trend, while the early warning reliability metrics continuously decline—FAR decreases from 18.2% to 7.9% and FRR drops from 16.5% to 6.8%. This performance improvement stems from the synergistic effect of the two weights: the adjacency matrix derived from the Pearson correlation coefficient captures the statistical association patterns of AUs in high-G training data, while the anatomical weight anchors physiologically plausible AU combinations (e.g., AU01-AU02 controlled by the frontalis muscle and AU06-AU12 linked to the zygomaticus muscle). Their balanced collaboration enhances the model’s ability to distinguish G-LOC precursor features from normal facial movements. The core cause of this performance degradation is that an excessively high

overemphasizes statistical correlations in the data, which may include spurious associations unrelated to G-LOC physiological mechanisms. Meanwhile, the weakened anatomical weight 1-

can no longer constrain the model through facial muscle synergy priors, leading to a reduction in the model’s generalization ability for dynamic AU interactions under varying G-load conditions.

Experimental results confirm = 0.65 as the optimal configuration, where the model achieves the peak of comprehensive performance—attaining the highest classification accuracy and the lowest error rates (FAR = 7.9%, FRR = 6.8%). This ratio means allocating 65% of the weight to the Pearson correlation-derived adjacency matrix fully leverages data-driven statistical patterns, while 35% of the anatomical prior weight ensures the model’s consistency with physiological reality. Mechanistically, this optimal balance addresses two key challenges in G-LOC detection: the Pearson correlation-based weight captures dynamic AU co-activation patterns observed in centrifuge training data, and the anatomical weight constrains the model to prioritize biologically meaningful AU combinations, avoiding overfitting to noise in the training data.

This nonlinear influence law provides important guidance for the practical deployment of G-LOC early warning systems: when is below 0.65, insufficient utilization of data-driven patterns results in suboptimal classification performance and high error rates, which may impair the system’s ability to detect subtle G-LOC precursors. In contrast, when is above 0.65, over-reliance on statistical correlations increases the risk of false alarms and missed detections in real-world aviation scenarios—outcomes that could trigger unnecessary flight interventions or fail to alert to impending G-LOC. In summary, the fusion coefficient exerts a significant nonlinear impact on model performance by mediating the balance between data-driven statistical patterns and physiology-based anatomical priors, with the optimal configuration = 0.65 maximizing the synergy of these two weights.