Fastener Flexibility Analysis of Metal-Composite Hybrid Joint Structures Based on Explainable Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

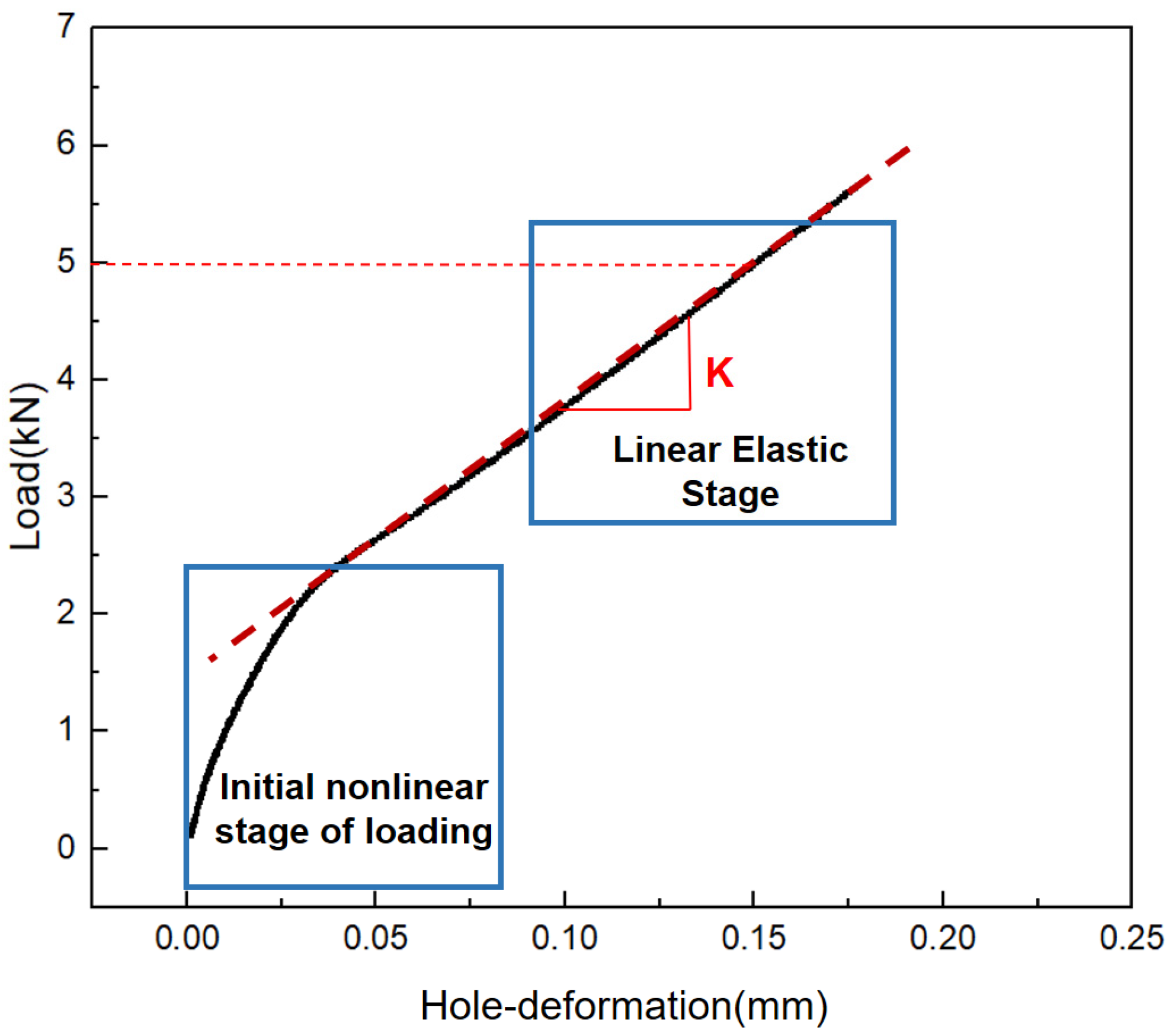

2. Numerical Modeling and Experimental Validation

3. Machine Learning-Based Flexibility Prediction Model

3.1. Database Generation

3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.3. ML-Based Flexibility Prediction Model Construction

3.4. Validation of the ML-Based Flexibility Prediction Model

4. Model Explanation

4.1. Model Explanation by SHAP

4.2. SHAP Result Analysis

4.3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, X.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Guo, X. Study on Axial Compression Performance of CFRP-Aluminum Alloy Laminated Short Tubes. Materials 2025, 18, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Fu, K.; Huang, T.; Liu, H.; Yang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y. Highly conductive CFRP composite with Ag-coated T-ZnO interlayers for excellent lightning strike protection, EMI shielding and interlayer toughness. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 279, 111448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.K.; Dong, Y.; Sarker, P.K.; Uddin, M.S.; Littlefair, G.; Dixit, A.R.; Chattopadhyaya, S. Joining of carbon fibre reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites and aluminium alloys—A review. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 101, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islami, D.P.; Muzaqih, A.F.; Adiputra, R.; Prabowo, A.R.; Firdaus, N.; Ehlers, S.; Braun, M.; Jurkovič, M.; Smaradhana, D.F.; Carvalho, H. Structural design parameters of laminated composites for marine applications: Milestone study and extended review on current technology and engineering. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delzendehrooy, F.; Akhavan-Safar, A.; Barbosa, A.Q.; Beygi, R.; Cardoso, D.; Carbas, R.J.C.; Marques, E.A.S.; da Silva, L.F.M. A comprehensive review on structural joining techniques in the marine industry. Compos. Struct. 2022, 289, 115490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, H.; Zhou, H.; Wei, Z.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, W.; Cheng, H.; Luo, B.; Zhang, K. Degradation mechanisms and mechanical behavior of composite-metal bolted/riveted joints in complex service conditions: A comprehensive review. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 182, 110037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, X. Analytical and experimental study on fastener connection compliance. Eng. Mech. 2013, 30, 470–475+480. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Q.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y. Research on typical connection structure fastener flexibility coefficient calculation method. Aeronaut. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Huth, H. Influence of fastener flexibility on the prediction of load transfer and fatigue life for multiple-row joints. In Fatigue in Mechanically Fastened Composite and Metallic Joints; ASTM STP: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1986; Volume 927, pp. 221–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, M.B.; Rosenfeld, S.J. Preliminary Investigation of the Loads Carried by Individual Bolts in Bolted Joints; NACA Technical Note: Boston, MA, USA, 1946; Volume 1051. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, G. Defining a Standard Formula and Test-Method for Fastener Flexibility in Lap-Joints. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, T.; Huang, Q.; Yin, Z.; Su, X. The modification of the formula for the aircraft structural fastener’s flexibility. Mech. Strength 2014, 36, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, Q.; Yin, Z.; Ma, K. Analysis of influence factors to the flexibility of aircraft structural fasteners. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aerosp. Eng. 2013, 32, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarringol, M.; Patel, V.I.; Liang, Q.Q. Artificial neural network model for strength predictions of CFST columns strengthened with CFRP. Eng. Struct. 2023, 281, 115784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.-T. Machine learning for structural engineering: A state-of-the-art review. Structures 2022, 38, 448–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lei, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, G.; Qiu, B. Fatigue life analysis of high-strength bolts based on machine learning method and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) approach. Structures 2023, 51, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, I.; Richards, N.; Ogasawara, T.; Tan, K.T. Machine learning algorithms for deeper understanding and better design of composite adhesive joints. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, D.S.; Sivasuriyan, A.; Devarajan, P.; Stefańska, A.; Wodzyński, Ł.; Koda, E. Carbon fibre-reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites in civil engineering application—A comprehensive review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, E.; Çalık, A. Failure load prediction of single lap adhesive joints using artificial neural networks. Alex. Eng. J. 2016, 55, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birecikli, B.; Karaman, Ö.A.; Çelebi, S.B.; Turgut, A. Failure load prediction of adhesively bonded GFRP composite joints using artificial neural networks. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2020, 34, 4631–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.K.; Mustapha, K.B.; Pagwiwoko, C.P. Delamination detection in composite plates using random forests. Compos. Struct. 2021, 278, 114676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, S. Neural networks and deep learning: Part II. In Machine Learning, 3rd ed.; Theodoridis, S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2026; pp. 997–1102. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals/book-companion/9780443292385 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Staniak, M.; Biecek, P. Explanations of model predictions with live and breakdown packages. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Soloviev, M.; Hooker, G.; Wells, M.T. Tree Space Prototypes: Another Look at Making Tree Ensembles Interpretable. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1611.07115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, B.; Lyu, Q.; Xie, W.; Guo, Z.; Wang, B. Compression after multiple impact strength of composite laminates prediction method based on machine learning approach. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 136, 108243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yossef, M.; Noureldin, M.; Alqabbany, A. Explainable artificial intelligence framework for FRP composites design. Compos. Struct. 2024, 341, 118190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Nasiri, H.; Ghorbani, O.; Friswell, M.I.; Castro, S.G.P. Explainable Artificial Intelligence to Investigate the Contribution of Design Variables to the Static Characteristics of Bistable Composite Laminates. Materials 2023, 16, 5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, H. Machine learning-based prediction and interpretability analysis of flexural capacity for CFRP-strengthened RC beams. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Qiu, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, J.; Feng, Z.; Long, J. An interpretable machine learning model for predicting bond strength of CFRP-steel epoxy-bonded interface. Compos. Struct. 2023, 326, 117639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapidžić, Z.; Nylander, A.M. Fatigue and failure testing of a hybrid CFRP-aluminum wing box at elevated temperature. Compos. Struct. 2023, 305, 116469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, P. Effects of hygrothermal ageing and temperature on the mechanical behavior of aluminum-CFRP hybrid (riveted/bonded) joints. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2023, 121, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ren, F.; Yan, G.; Tang, J.; Cai, C.; Zhang, C.; Gu, X.; Xu, X. Compressive behavior of composite stiffened panels with hybrid bonded-bolted stiffener terminations: Experimental and numerical investigations. Thin-Walled Struct. 2026, 219, 114160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Special Metals Corporation. INCONEL® Alloy 718. In Technical Bulletin; Special Metals Corporation: Huntington, WV, USA, 2007; Available online: https://www.specialmetals.com/documents/technical-bulletins/inconel/inconel-alloy-718.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2007).

- ASTM D5961M-23; Standard Test Method for Bearing Response of Polymer Matrix Composite Laminates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Sahoo, P.; Barman, T.K. ANN modelling of fractal dimension in machining. In Mechatronics and Manufacturing Engineering; Paulo Davim, J., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 159–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Kwak, H.M.; Choi, J.M.; Eom, J.G.; Kim, H.J.; Chung, W.J.; Joun, M.S. Experimental and numerical study on fillet rolling of a Ti6Al4V alloy aircraft bolt focusing on fatigue life. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 151, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Guimarães, B.; Bartolomeu, F.; Miranda, G.; Silva, F.S.; Carvalho, O. Multi-material Inconel 718—Aluminium parts targeting aerospace applications: A suitable combination of low-weight and thermal properties. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 158, 108913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Lv, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Xue, Y. Influence of creep on preload relaxation of bolted composite joints: Modeling and numerical simulation. Compos. Struct. 2020, 245, 112332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.-B.; Xu, H.; Zhu, Y.-T.; Bu, G.-Y. Experimental and numerical investigation on thermomechanical behavior of diverse plain-woven CFRP bolted joint configurations. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 218, 114155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, T. Dependence of slip behavior of bolted connection on contact pressure and splice plate thickness. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2025, 237, 110123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocchi, C.; Robinson, P.; Pinho, S.T. A detailed finite element investigation of composite bolted joints with countersunk fasteners. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2013, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussnain, S.; Sajid, Z.; Shah, S.; Megat-Yusoff, P.; Hussain, M. Effect of bolt size and fibre orientation on the bearing performance of resin-infused thermoplastic and thermoset 3D woven composite double-lap joints. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2024, 38, 1818–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Sabbrojjaman, M.; Tafsirojjaman, T. Effect of bolt size on the bearing strength of bolt-connected orthotropic CFRP laminate. Polym. Test. 2023, 118, 107894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. Research on Pin Load Distribution of Mechanically Connected Composites Under Shear Load. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Material | Property | Value | Material | Property | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laminae [31] | E11 | 134,600 MPa | Al [32] | E | 72,000 MPa |

| E22 | 8700 MPa | 0.33 | |||

| E33 | 8700 MPa | 2.32 × 10−5 | |||

| 12 | 0.27 | Ti [33] | E | 113,000 MPa | |

| G12 | 3900 MPa | 0.34 | |||

| G13 | 3900 MPa | 9.0 × 10−6 | |||

| G23 | 2900 MPa | Inconel [34] | E | 199,000 MPa | |

| 11 | 2.0 × 10−7 | 0.28 | |||

| 22/33 | 2.8 × 10−5 | 7.42 × 10−6 |

| Strain | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test () | 836 | 1008 | 842 | 1076 | 681 | 287 | 772 | 261 |

| FE () | 897 | 1045 | 897 | 1044 | 771 | 262 | 771 | 261 |

| Error (%) | −7.30% | −3.67% | −6.53% | 2.97% | −13.22% | 8.71% | 0.13% | 0.00% |

| Feature | Name/Value |

|---|---|

| Bolt material | Ti-6Al-4V/Inconel 718 |

| Preload (N·m) | 2.5/5 |

| Temperature (°C) | −55/20/45 |

| Plate thickness ratio | 0.4/0.6/1 |

| Bolt diameter (mm) | 3.97/4.76/6.35 |

| Type of bolt | Dome/Countersunk |

| Mean Square Error (MSE) | R-Squared (R2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Training set | 0.0015 | 0.9984 |

| Test set | 0.0033 | 0.9968 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Niu, X.; Zhang, X. Fastener Flexibility Analysis of Metal-Composite Hybrid Joint Structures Based on Explainable Machine Learning. Aerospace 2026, 13, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010058

Niu X, Zhang X. Fastener Flexibility Analysis of Metal-Composite Hybrid Joint Structures Based on Explainable Machine Learning. Aerospace. 2026; 13(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Xinyu, and Xiaojing Zhang. 2026. "Fastener Flexibility Analysis of Metal-Composite Hybrid Joint Structures Based on Explainable Machine Learning" Aerospace 13, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010058

APA StyleNiu, X., & Zhang, X. (2026). Fastener Flexibility Analysis of Metal-Composite Hybrid Joint Structures Based on Explainable Machine Learning. Aerospace, 13(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010058