1. Introduction

Laminated composite (LC) smart skin, with numerous advantages such as light weight, high strength, and corrosion resistance, has found broad applications in various engineering fields, including aerospace [

1], aircraft [

2,

3], navigation [

4,

5], and more. As a result, a significant number of researchers have been drawn to the development of laminated composite structures and the accurate prediction of their structural responses. This paper cites only a select few representative references, and for more comprehensive details, the reader is referred to [

6]. The assessment of structural conditions is crucial in ensuring the safe operation of industrial equipment. Safety is particularly critical in aviation, where structural integrity is paramount, as a failure can often result in catastrophic consequences. For this reason, the structural health monitoring (SHM) technique is proposed for real-time assessment of structures. It utilizes real-time measurements, such as strain, acceleration, and temperature, from discrete sensors mounted on the structure to predict the health state of the structure [

7,

8]. This approach is effective in reducing operating costs and manpower, while improving overall structural safety [

9]. Shape sensing technology is a critical component of SHM systems, providing robust technical support for the development of monitoring and control strategies for deformed structures. Structural shape sensing allows for real-time displacement reconstruction through discrete strain measurements, which highlights its nature as an inverse problem.

In recent years, various methods for anti-shape sensing problems have become a core research focus. This paper provides a brief overview and comparison of their main contributions. The structural kinematic variables, i.e., displacements and rotations, are predicted by integrating measured strains [

10]. This methodology was originally proposed for plate elements and has been improved for beam and plate structures [

11,

12]. Additionally, the structural deformation field can also be regarded as a weighted superposition of basis functions [

13]. However, this approach requires a priori interpolation basis functions or the vibrational mode shapes of the estimated structures [

14], from which displacements can be determined by calculating the unknown weight coefficients from the discrete strain measurements [

15]. In order to reduce the dependence of deformation monitoring on mathematical models and prior experience, an FBG-based approach, along with a data-driven and finite element model, has been proposed [

16]. Among the various algorithms derived from existing literature, the inverse finite element method (iFEM) uses mathematical models to calculate structural displacement fields based on strain measurement results. Furthermore, this approach does not require any prior knowledge of material parameters or load conditions, but rather performs analysis based solely on strain measurement data. Moreover, it is convenient for the iFEM methodology to obtain strain measurements, where the strain sensors are typically bonded to the external surface of beam or plate structures [

17]. Compared to the reconstruction methods mentioned above, the iFEM formulation has likely received the most widespread attention and recognition, as it is independent of interpolated shape functions or prior knowledge of the modal characteristics of structures and does not require an extensive model to produce reliable projections [

18].

The iFEM approach was originally presented for shape sensing of plate and shell elements. As a result, many inverse-shell elements have been developed, including the three-node shell element (iMIN3) [

19], four-node shell element (iQS4) [

20], and the 8-node curved shell element [

21]. These efforts have been further enhanced and applied to analyze composite structures, with engineering applications in wing-shaped geometries [

22,

23], stiffened panels [

24,

25], and marine structures [

26,

27]. Moreover, in order to avoid the non-invertibility of the reconstruction matrix, strain sensor placement optimization models have been established through a multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm [

28,

29]. Specifically, Ghasemzadeh et al. coupled iFEM with the genetic algorithm (GA) to reduce the number of sensors while maintaining displacement reconstruction accuracy [

30]. Furthermore, the iFEM formulation has also been applied to detect damage in metallic and composite structures [

31,

32]. In addition, researchers such as Gherlone developed a theoretical method based on 1D iFEM to address the limitations of the 2D iFEM method in accurately reconstructing deformation in beams and frame structures [

33]. Subsequently, this approach has been utilized to tackle cross-sectional complexities and composite structures [

34]. The engineering performance of the 1D iFEM formulation has been demonstrated based on circular and airfoil beams [

34], radio telescope reflectors [

35], and subsea pipelines [

36], among others.

In recent years, Zhao et al. coupled the iFEM with strain gradient theory to address geometrically nonlinear deformation problems of the Timoshenko beam, Euler-Bernoulli beam, and composite beam [

37,

38,

39]. Li et al. developed an iterative linearization iFEM formulation based on the iQS4 unit, which predicts geometric nonlinear deformation by linearizing nonlinear responses [

40]. To enhance the computational capability of nonlinear iFEM models, Wu et al. proposed an element-by-element iFEM approach constructed from the absolute nodal coordinate formulation (ANCF) [

41].

Although previous shape sensing methods have been proven effective in many studies and supported by numerical calculations and experimental validations, their applicability to smart skin structures with warping deformations has not been thoroughly explored. This is particularly true for smart skin structures, especially in composite material structures, which exhibit different properties. Under loading, the anisotropic behavior of the materials leads to the simultaneous occurrence of bending, torsion, and warping. Due to the shear deformation of these multilayer materials, the cross-section undergoes warping, which significantly affects the overall deformation. However, traditional iFEM beam and shell models are typically based on classical beam theory (such as Euler–Bernoulli beam or Timoshenko beam theory), which assumes that the beam cross-section remains planar during deformation and does not account for warping deformations. In contrast, the method presented in this paper incorporates a more detailed geometric description and material response model, introducing a warping function that considers the effects of warping deformation on the cross-section.

To address this issue, a new iFEM method is proposed in this paper, specifically designed for modeling warping deformations in smart skin structures. This method effectively describes warping deformations in smart skins by defining a warping function and integrating it into the deformation theory of laminated smart skin structures. Validation results on a smart skin composite airfoil structure demonstrate that the proposed shape sensing model can accurately capture warping deformations, providing a new and more precise solution for shape sensing in smart skins.

The structure of the manuscript is delineated as follows:

Section 2 reviews the displacement field theory, defines the warping function, and derives the constitutive equations. In

Section 3, the shape sensing model is formulated based on the variational approach.

Section 4 presents the determination of the reconstruction input, including the displacement interpolation functions and experimental section strain functions.

Section 5 elaborates on the numerical calculations and experimental tests to validate the reconstruction accuracy of the proposed iFEM. The conclusions of this work, along with potential avenues for future investigation, are discussed in

Section 6.

2. Basic Theory

Consider a straight-line smart skin wing-shaped beam with a constant cross-sectional geometry. For the global structure, an orthogonal Cartesian coordinate system (

x,

y,

z) is employed as the reference frame; for the local shell wall, a curvilinear coordinate system (

x,

s,

n) is adopted, as presented in

Figure 1. In each reference system, displacement and rotation are defined according to the forward direction of the coordinate axis. The pole

P with coordinate (

xp,

yp,

zp) is the shear center of the airfoil cross-section (see

Figure 1b). For the deformation description of the airfoil structure, the following assumptions are made:

- (i)

The cross-section contour of the airfoil structure is assumed to remain rigid within its own plane, with no consideration given to sectional distortion.

- (ii)

After deformation, the normal on the undeformed median plane remains perpendicular to the deformed median plane.

- (iii)

The warping function is defined with respect to point P or the central shear.

- (iv)

The stress components σxx, σxs, and σxn, as well as the strains and curvature components εx, γxs, and γxn, are considered the most significant, and other components are assumed to be negligible.

According to small strain assumption theory, the mid-plane deformation of the shell wall can be expressed in terms of three Cartesian components of the displacement vector as follows:

where

y,s and

z,s are the trigonometric functions

and

, respectively. Angle α represents the orientation between

n- and

y-axes, as shown in

Figure 1b. (

,

,

,

,

) are the kinematic variables of the shell mid-plane; (

u,

v,

w,

θx,

θy,

θz) are the global kinematic variables, which represent the displacements and rotations of the shell. The symbols

rn and

rt represent the normal and tangential coordinates of point P (

x,

y,

z) on the shell mid-plane along

n- and

s-axes, respectively. By iterating through the local coordinates along the airfoil cross-section, the normal coordinate

rn and tangential coordinate

rt of any point can be calculated.

is an additional kinematic variable and is used to describe the warping deformation of the cross-section, which can be defined as follows:

where the functions

rn and

rt are expressed in the following form:

with

The functions

Z(s) and

Y(s) are defined by the relationship between the arc length coordinate

s and the global coordinates

y and

z, with the explicit form provided in the following sections. The coordinates

y(

s) and

z(

s) of a generic point in the cross-section are defined relative to the middle-line coordinates

Y(

s) and

Z(s). Pursuant to the small-strain–displacement theory, the strain field is obtained

with

where transverse coordinates (

y,

z) can be expressed in terms of arc length coordinate

s, such as

z =

f(

s),

y =

g(

s), which can be determined based on the cross-sectional shape of the specific airfoil structure.

G0 and

F0 are the distribution functions of the shear strains. Due to the two transverse shear loads,

and

refer to the maximal shear strains present at the contour coordinates of the cross-section, respectively. Furthermore, based on our previous research results [

42], the strain terms

and

can be described by the section strains (

e4 and

e5) as follows:

where

and

.

and

are constant and are determined according to the presented calculation procedure in the literature [

42]. Meanwhile, Equation (3a) can be expressed in another manner as follows:

where

e(

u) = {

e1,

e2,

e3,

e4,

e5,

e6}

T are the theoretical section strains and are presented as

According to classical thin plate theory, the correlation between the resultant stress, stress coupling, and shell strain is given as follows [

43]:

where

N,

M, and

V represent the resultant stress and couple of the laminated structure;

ε contains the strains and shear strains in the

x-

s plane;

κ represents the curvatures of the airfoil structure;

γ is the shear strain in the

x-

n plane. The symbol

k is the shear correction coefficient.

Aij,

Bij, and

Dij are the reduced stiffness components of materials referenced to the

x-

s-

n coordinate system, which can be expanded in the following form:

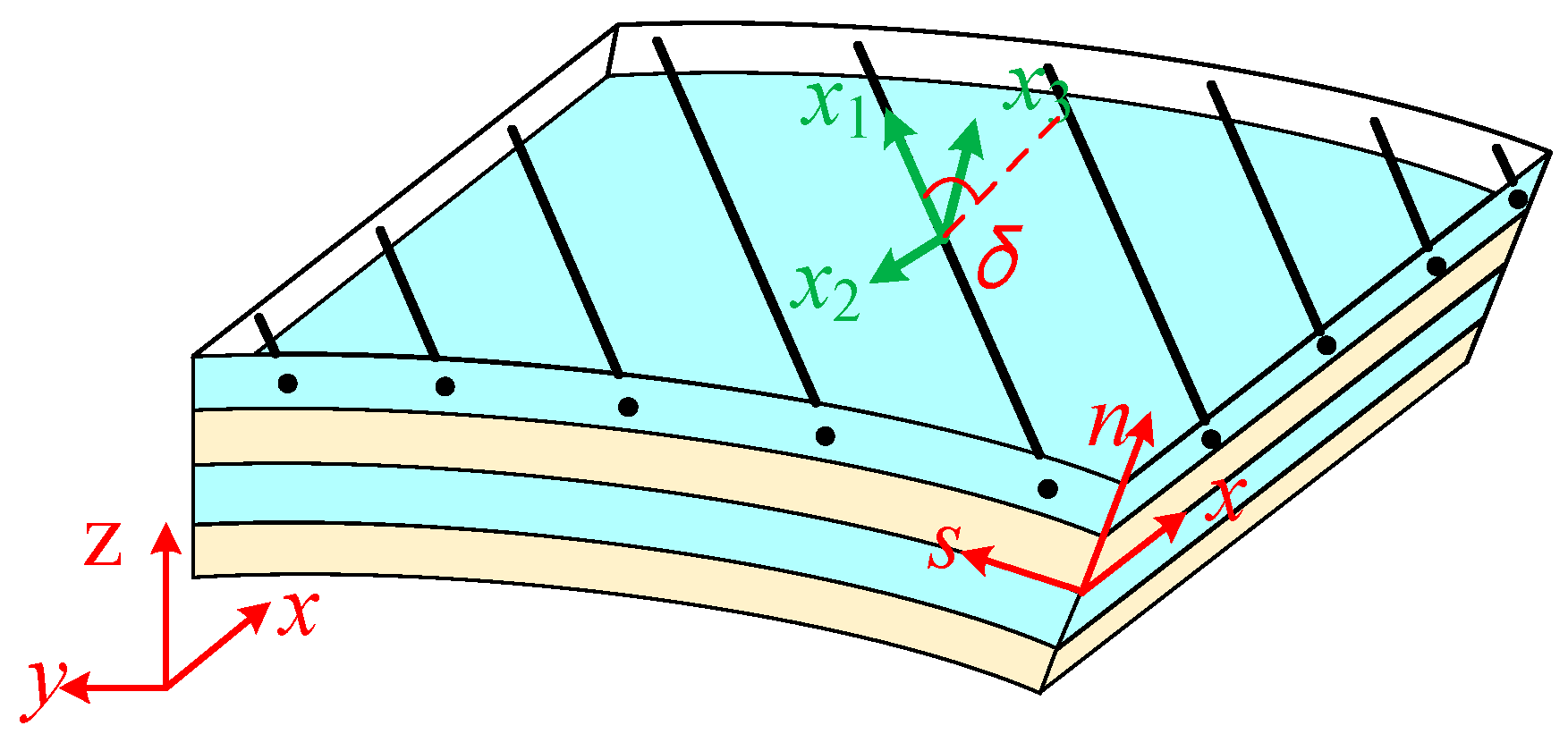

where n represents the overall number of layers in the wing structure; h

r and h

r−1 indicate the spacing from the shell reference surface to the outside and inside surfaces of the rth layer;

is the transformed stiffness depending on the ply stiffness and fiber orientation δ, as shown in

Figure 2, the specific matrix form can be found in [

44]

These elastic material constants

Qij are defined in the material coordinates (

x1,

x2,

x3) and are calculated based on the engineering constants, such as

where

E is Yong’s modulus, G stands for the shear modulus, and

μ stands for the Poisson ratio.

Furthermore, in the Cartesian coordinate system, the cross-section forces can be described in terms of the generalized beam strain and stiffness matrix (the derivative process can be found in reference [

45]) as follows:

in which

Here,

K is a (7 × 7) rearranged stiffness matrix, and non-zero elements can be defined as follows:

where

b is the airfoil’s chord length. When the distributed loads

qx,

qy, and

qz are applied to the beam, the equilibrium equations are

Combining Equations (6a) and (7a), the transformation relation can be obtained, as given by

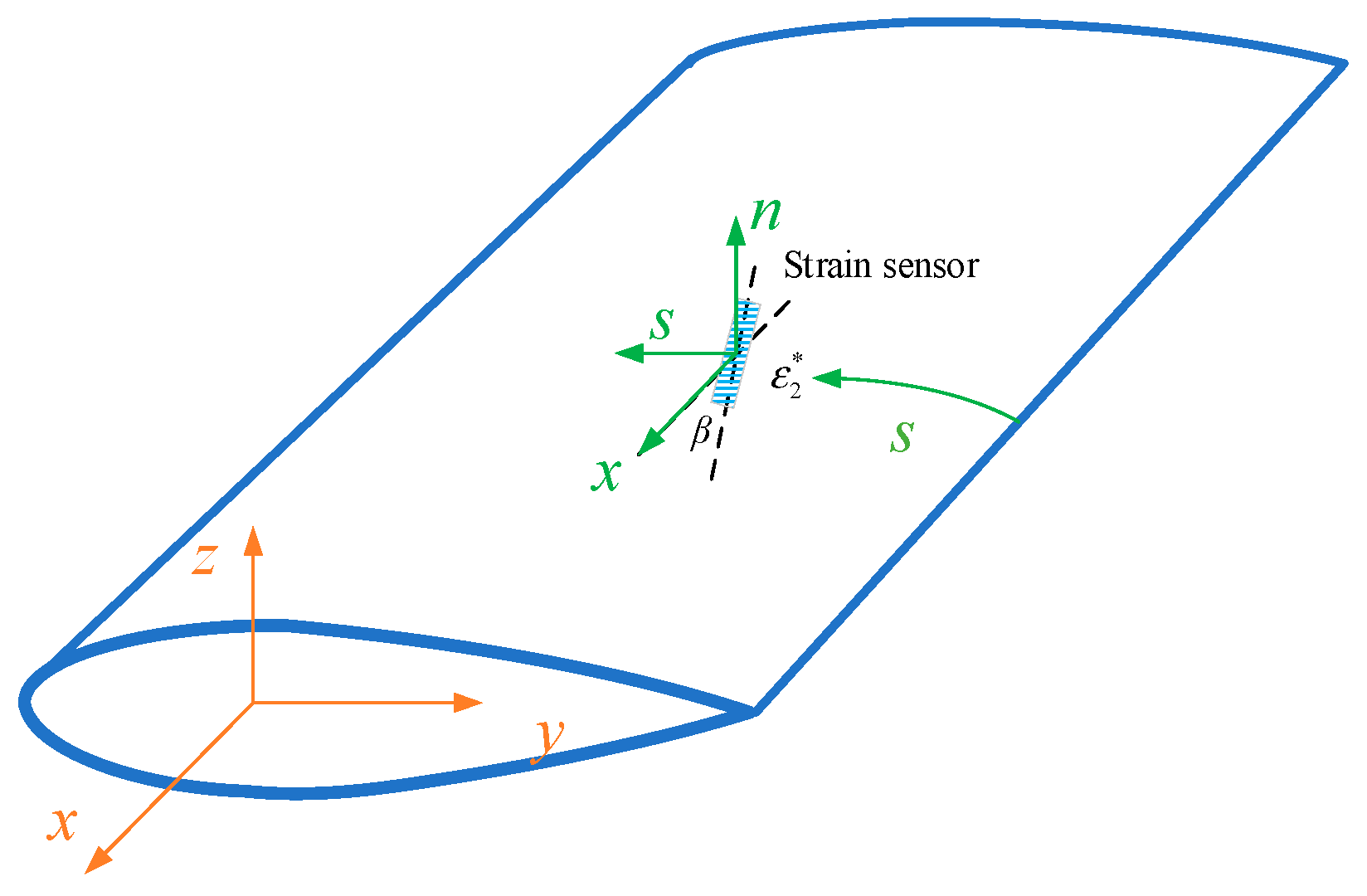

3. iFEM Formulation for Airfoil Beams

In order to monitor the deformed shape of the airfoil beam structure, a least squares functional that matches the complete set of theoretical section strains,

e(

u), to the practical section strains,

eε, is minimized with respect to the kinematic variables,

u, which can be expressed as follows:

The airfoil beam can be discretized into elements. Thus, the element kinematic field in the pole-axes is calculated from an interpolation based on

C0—continuous shape interpolation functions, i.e.,

where

N(

x) is the interpolation shape function, and

ue is the nodal degrees of freedom (DOF).

Then, plugging Equation (9) into Equation (4) yields the theoretical section strains in terms of DOF as

where the matrix

J includes the first derivatives of the shape function

N(

x). Equation (8) can be reformulated after the beam structure is discretized into n inverse-elements, as follows:

where

L stands for the length of the beam;

x is the coordinate location for theoretical section calculation; the exponent

εi represents the measured section strains, which are derived from the discrete surface strain measurements. Plugging Equation (10) into Equation (11) and then Equation (11) is able to be presented in quadratic form as follows:

where the parameter c

e is invariant. Meanwhile, matrices

ke and

fe are given by

and

where matrices

K and

F are analogous stiffness matrix and load vectors, respectively. Matrix

K is a function of section strain location

xi; the vector

F is solely affected by the strain measurements. By minimizing function Φ and differentiating with respect to the nodal degrees of freedom

ue, a shape perception model can be obtained as follows:

The solution of the above equation for the unknown node DOF is efficient, which can be obtained based on the inverse operation of matrix K and the matrix–vector multiplication, ue = K−1F, where K−1 remains unchanged for a set of determined strain sensor schemes.

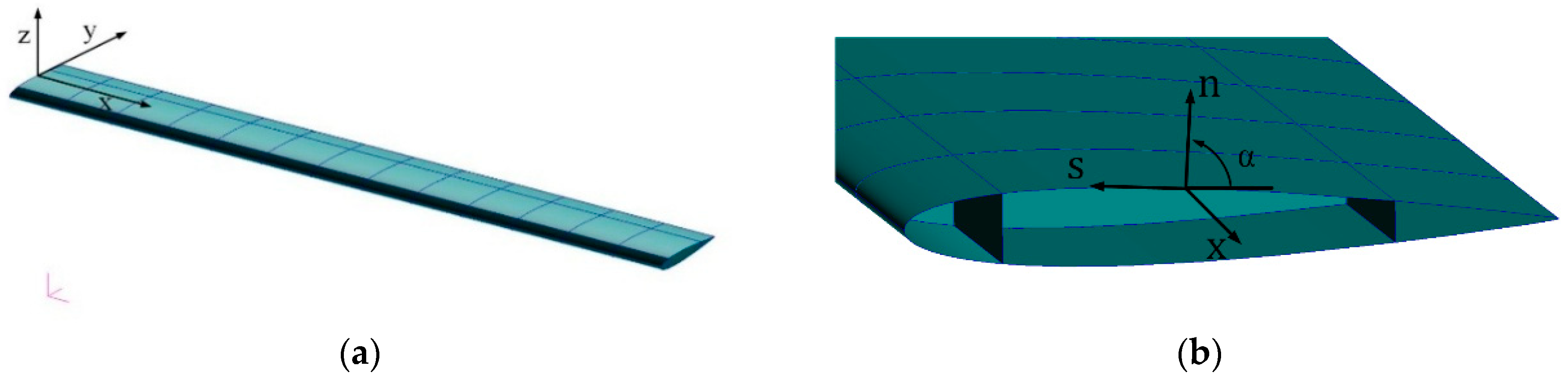

5. Applications

In this part, the finite element software is exploited to analyze the airfoil structure and thus verify the reconstruction accuracy of the proposed iFEM algorithm. The size of the airfoil is

L = 2125 mm, width

b = 200 mm, and height

h = 25 mm. As presented in

Figure 4, the airfoil structure is composed of a skeleton member and a skin, in which the composite stack is

3s, and each layer is 0.3 mm thick. The mechanical property characteristics of the material are shown in

Table 1, where

Ei (

i =

x,

y,

z) is the elastic modulus,

Eij (

i,

j =

x,

y,

z) is the shear modulus, and

is Poisson’s ratio.

After modeling the composite airfoil in MSC Patran 2020 and establishing the 3D coordinate system (

x,

y,

z) and local coordinate system (

x,

s,

n) (shown in

Figure 4a,b), shear and torsional loads are applied to the airfoil structure. The deformation field information can then be extracted from the analysis results.

5.1. Numerical Method for Calculating Coefficients and Variation Function

For a given airfoil structure, these variable functions {f1, f2, f3} and parameters {kεy, kεz} can be further determined based on the results of the FE analysis, and their values are independent of the type and magnitude of external loads.

This section describes the specific solution steps: first, based on geometric principles, the transformation between the circumferential distance

c of the airfoil and the coordinate

y can be determined, as described by Equation (25).

For the airfoil cross-sectional structure, the airfoil’s cross-sectional profile is represented by the function

d(

y), and the arc length

c can be determined by the derivative of

d(

y). In this study, the coordinates of the nodes (

xi,

yi) on the section extracted from the finite element model are used to interpolate and fit

d(

y) using a 5/2 rational piecewise function. The geometric characteristics of the function

d(

y) and its mathematical expression are shown in

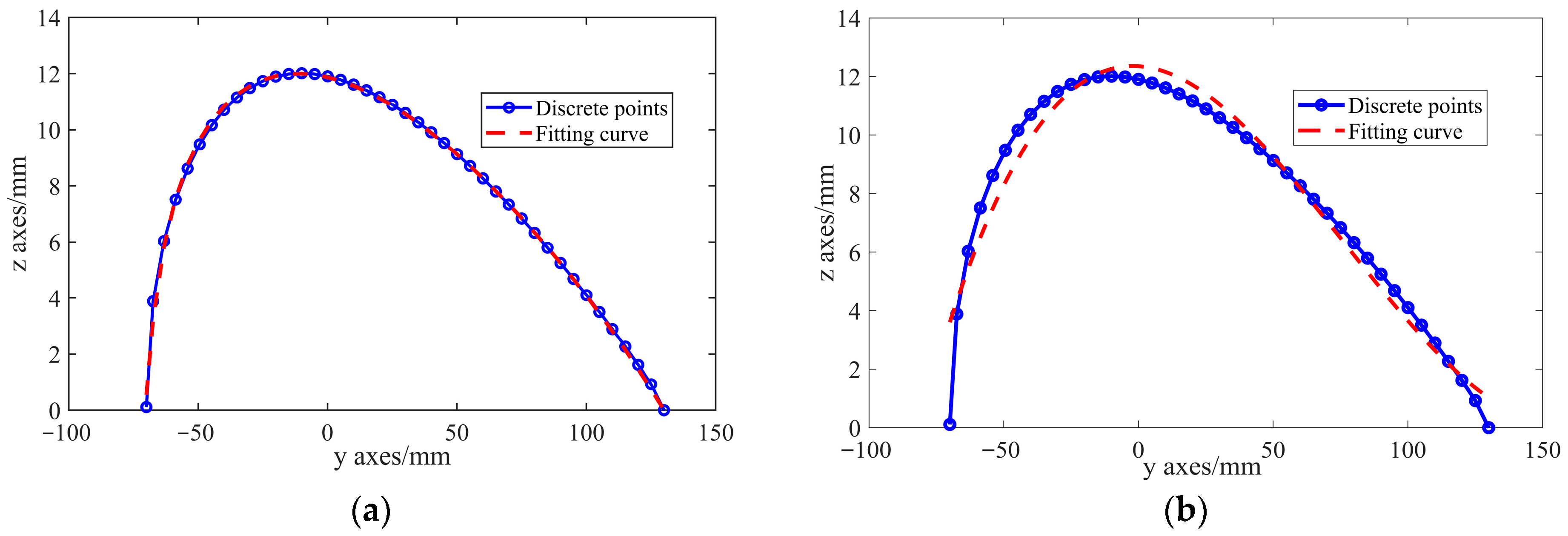

Figure 5 and described by Equation (26) (

). Compared to traditional polynomial fitting methods, such as a third-order polynomial function, which exhibit significant errors in regions with large airfoil curvature, the 5/2 rational function provides a more accurate fit for complex airfoil geometries, particularly in regions with sharp bends and significant local geometric changes.

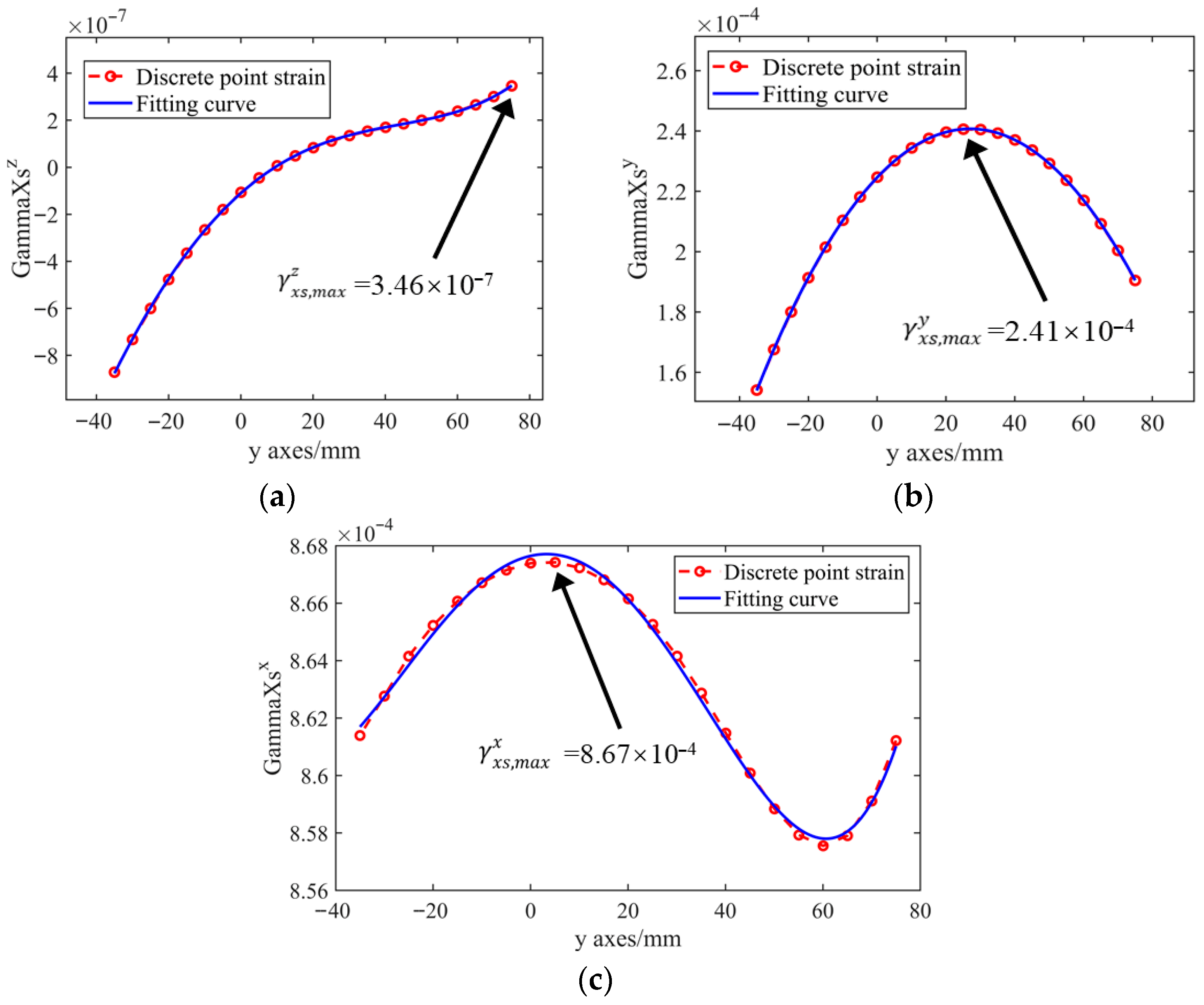

When shear loads and bending loads act separately on the wing structure, the shear strains

,

, and

can be obtained at

xi = 1060 mm. By substituting the above shear strains and the cross-section angle function

into Equation (27),

Here, the shear strains

and

can be computed at all the nodes (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). For obtaining {

f1(

c),

f2(

c),

f3(

c)} specifically, when load

Fy or

Fz is applied, the maximum value from the results of one iteration cycle is selected as

or

. Combining this with Equation (28) allows

f2 and

f3 to be calculated;

f1 is obtained similarly.

Apply a unit torsional load Mx to the model and calculate f1 using Equations (27) and (28).

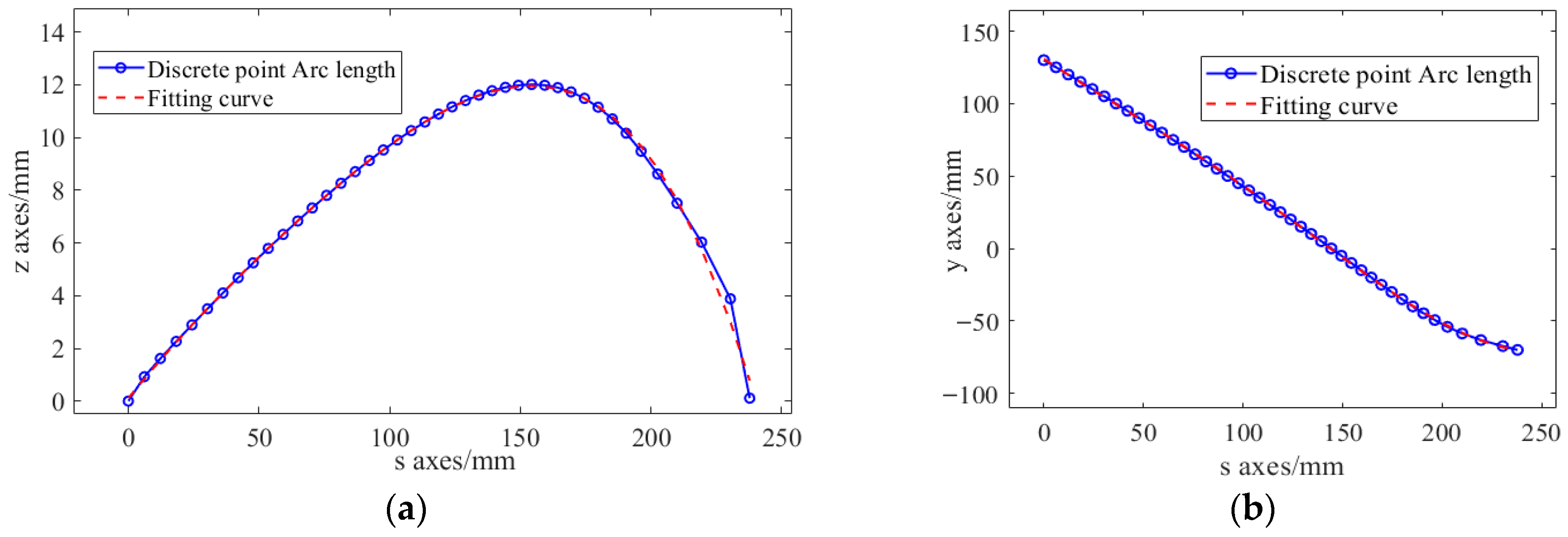

Using the arc length formula, the arc length value corresponding to any point on the curve can be calculated. By associating this arc length value with the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the wing section, the functional relationships between arc length and the

z-axis (

Z(

s)) and between arc length and the

y-axis (

Y(

s)) are established and fitted with quartic polynomial curves, as shown in Equations (29) and (30). The fitting results are presented in

Figure 6. Subsequently, substituting Equations (29) and (30) into Equation (2b), the

rn and

rt coordinates of any point

P on the plane can be determined, thereby enabling the further derivation of the deformation function

.

where

s represents the arc length, while

Z(

s) and

Y(

s) represent the coordinate relationships of the cross-section along the

z and

y directions, respectively, as they vary with the arc length. The aforementioned polynomials are obtained through fitting and are used to describe the geometric distribution characteristics of the structure along the arc length direction.

By substituting the variational functions

=

G0 and

=

F0, and the

kεy,

kεz obtained from [

42] into Equation (24), the transformation relationship between the surface strain and the neutral axis strain can be established.

5.2. Verification of the iFEM Reconstruction Method

To validate the iFEM method, experimental studies were conducted on the airfoil structure under static loading conditions. Surface strain data were collected from the high-precision finite element model shown in

Figure 4, with the extraction locations provided in

Table 2. Using the deformation reconstruction model developed in this study, the wing displacement was reconstructed. To evaluate the load conditions that may be encountered in practical applications, two experimental setups involving shear and torsional loads were implemented to assess the reconstruction accuracy of the iFEM model under different loading conditions.

The sensor arrangement covers the entire span of the airfoil, including the leading edge, midsection, and trailing edge. This arrangement helps capture strain data at different locations on the airfoil, reflecting the varying load conditions experienced by the structure.

To comprehensively evaluate the reconstruction performance of the iFEM model proposed in this paper, this paper compares the Non-Warping-iFEM approach (based on classical beam theories such as Euler–Bernoulli and Timoshenko beams without considering warping deformation) with the Warping-iFEM approach (which accounts for warping deformation in this paper) under multiple loading conditions. The comparisons are conducted using displacement data extracted from Patran 2020 software. Additionally, this paper establishes evaluation criteria for reconstruction accuracy to quantify performance differences between the methods:

Here, the maximum absolute displacement error is denoted as MER, and disp(x) shows the displacement of each observation point along the longitudinal axes at the midpoint of the upper surface of the wing. The superscripts “reconstruction” and “PATRAN” refer to displacement data obtained using the deformation reconstruction method and Patran 2020 analysis, respectively. To further assess the accuracy of displacement estimation, the root mean square error (RMS) serves as an indicator; additionally, the relative root mean square error (RRMS) is introduced, defined as the proportion of the RMS value to the maximum displacement value in PATRAN analysis.

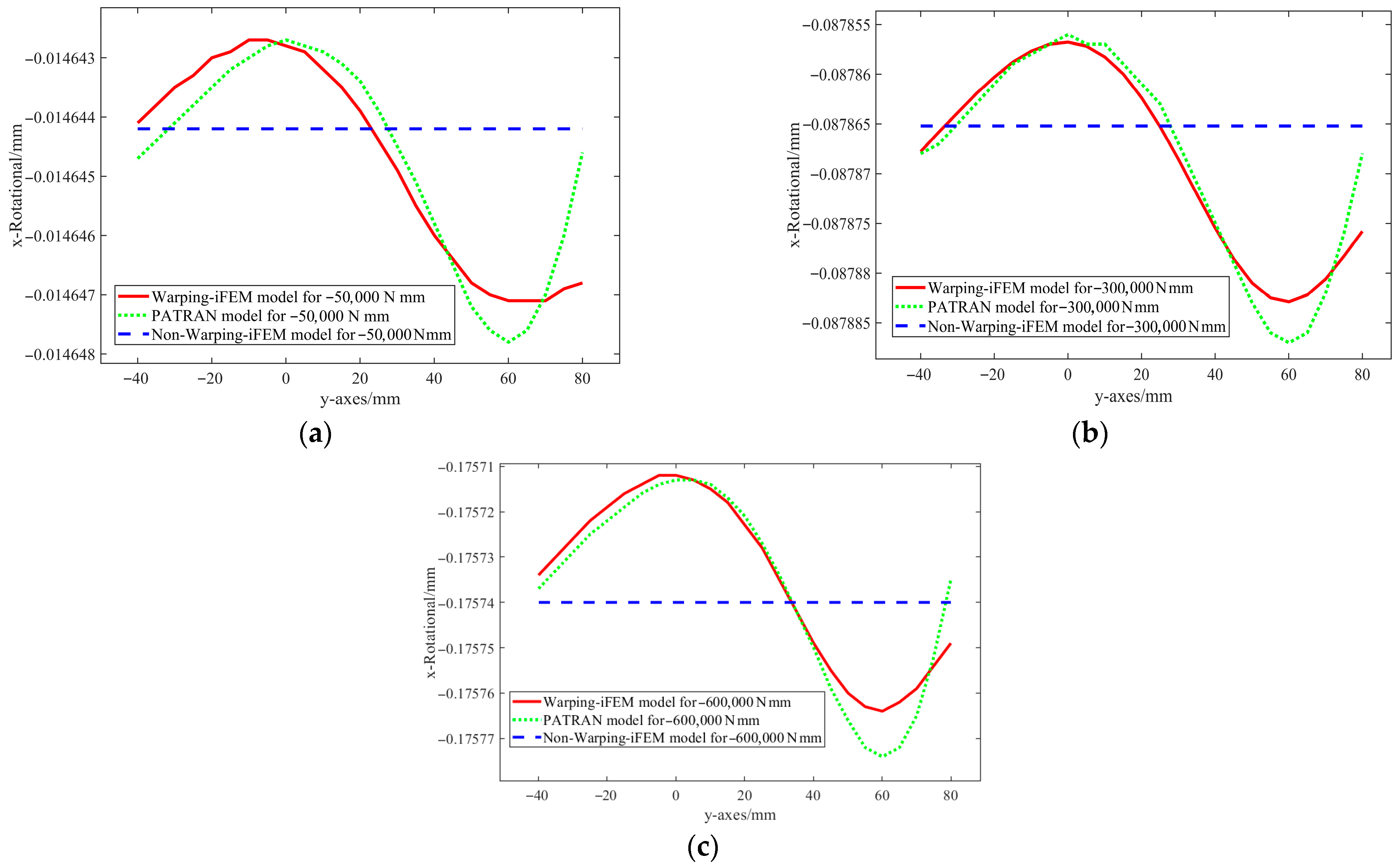

Under torsional loads,

Figure 8a–c show significant warping deformation characteristics in the wing cross-section. According to the sectional twist angle results, the Warping-iFEM calculation exhibits a non-uniform distribution along the

y-axis, which is highly consistent with the Patran 2020 results. In contrast, the Non-Warping-iFEM results approach a horizontal distribution, with significant deviations from the finite element solution, indicating that neglecting the warping effect underestimates the local torsional deformation. Furthermore, under different loading conditions (Mx = −50,000 N·mm, −300,000 N·mm, and −600,000 N·mm), the fluctuations in the twist angle caused by warping increase with increasing load, in accordance with the physical laws of structural twist deformation. Therefore, considering the warping effect is crucial for accurately predicting the torsional deformation of wing cross-sections.

When applying concentrated loads, the Warping-iFEM method developed in this study and the conventional Non-Warping-iFEM method reconstruct displacement based on the obtained independent stress information (typically predicting times less than one second).

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 and

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3,

Table A4,

Table A5 and

Table A6 show the reconstruction accuracy analysis.

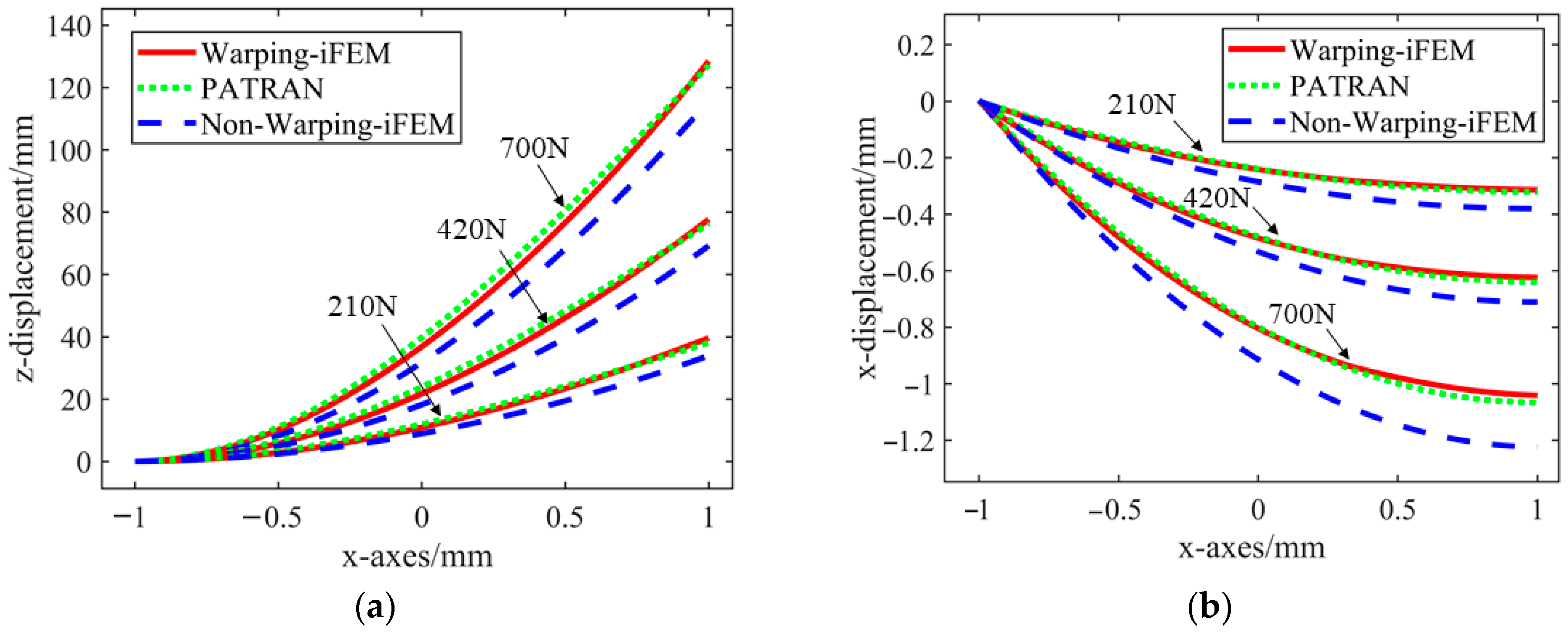

The figure shows a comparison of shear displacement in the Z direction.

Figure 9a,b show that the reconstructed displacement is close to the theoretical displacement under the three applied loads.

Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3 show that the proposed Warping-iFEM method achieves significantly higher accuracy compared to the Non-Warping-iFEM strategy. Specifically, both

MER and

RRMS are significantly reduced. In the

x-direction,

MER decreased from approximately 0.16 mm to 0.013 mm, and

RRMS decreased from nearly 12% to 1.78%; in the

z-direction,

MER decreased from approximately 12.63 mm to 3.85 mm, and

RRMS decreased from 7.5% to 1.75%. Additionally,

RRMS continued to decrease with increasing load, indicating that the influence of iFEM error weakens as deformation increases, with the error level ultimately converging to within 2%.

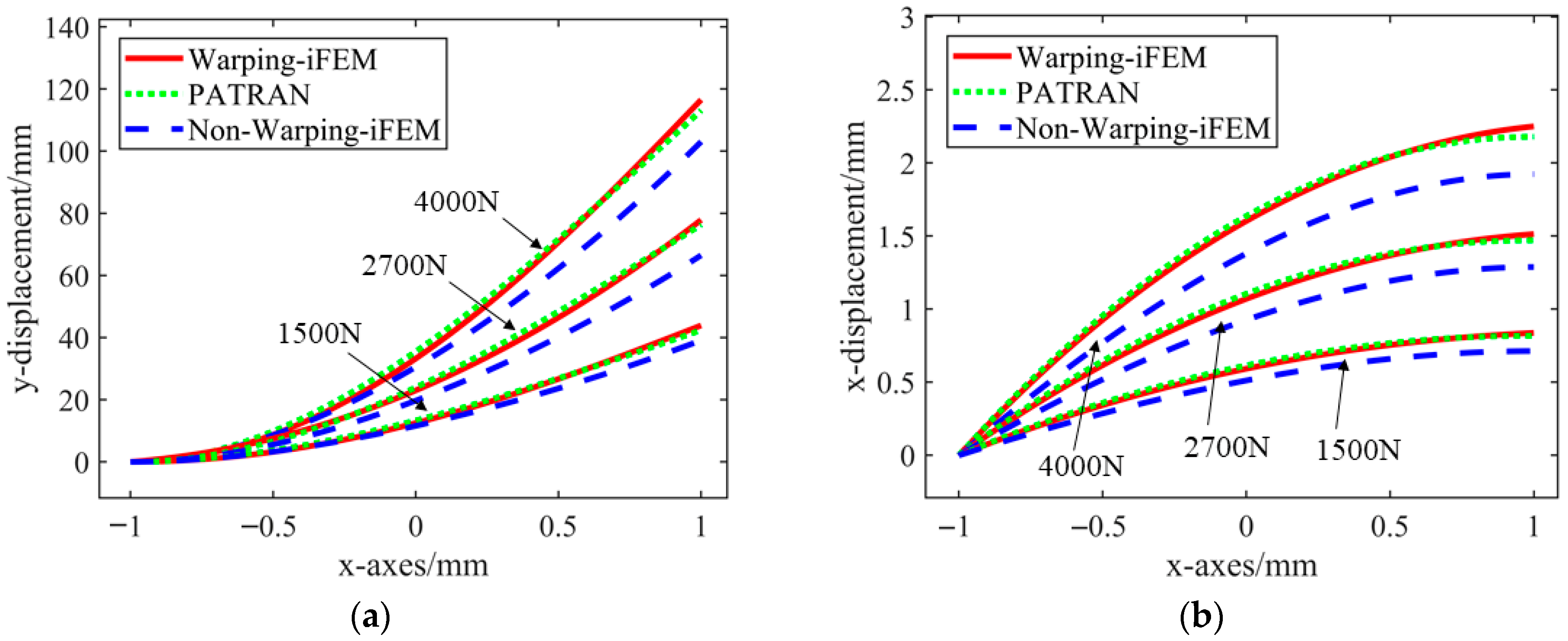

Figure 10 shows a comparison of shear displacement in the Y direction.

Figure 10a,b show that the reconstructed displacement is close to the theoretical displacement under the three applied loads.

Similarly, as shown in

Table A4,

Table A5 and

Table A6, the proposed Warping-iFEM significantly improves reconstruction accuracy. Specifically, both

MER and

RRMS are significantly reduced: in the

x-direction,

MER decreases from approximately 0.27 mm to 0.07 mm, and

RRMS decreases from nearly 11% to 1.77%; in the

y-direction,

MER decreases from approximately 10.63 mm to 3.43 mm, and

RRMS decreases from 7.58% to 1.77%. Additionally, as the load increases,

RRMS continues to decrease, indicating that the iFEM error influence weakens as deformation increases, ultimately converging to within 2%.

In addition,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 reveal that the Warping-iFEM method proposed in this paper more accurately matches the theoretical displacement curves in three directions (

x,

y, and

z) compared to the conventional Non-Warping-iFEM strategy. In contrast, in the Non-Warping-iFEM method, the blue curve deviates significantly from the theoretical displacement. This is because the effects of distortion deformation on shear strain and wing beam section deformation have not been taken into account.

Due to unavoidable measurement errors caused by noise or the acquisition system in strain gauge measurements, to validate the reliability and robustness of the proposed Warping-iFEM method, measurement errors were simulated by introducing a randomly distributed normal noise signal into the extraction of surface strain information, as shown in Equation (33):

where

εnoisy and

εture represent strain data with and without noise influence, respectively; Δ

r denotes a Gaussian random number with mean 0 and standard deviation

σ(Δ

r). Based on the method proposed in this paper, under the operating condition of

Fz = 700 N, normally distributed noise signals with a mean of 0 and standard deviations of 1% and 2% of the strain were added. The reconstruction comparison results are shown in

Table 3.

The comparison results demonstrate that the Warping-iFEM method maintains high reconstruction accuracy even after introducing 1% and 2% noise. Although the MER and RMS in the x and z directions slightly increased with the elevated noise levels, the RRMS consistently remained between 1.90% and 2.07%. This demonstrates the method’s strong robustness to noise, enabling it to effectively handle measurement errors and validating its reliability and robustness for practical applications.

Based on all the analysis results presented above, it can be concluded that the Warping-iFEM model proposed in this paper demonstrates exceptional reconstruction capabilities, making it a reliable and precise tool for predicting the spatial state of UAV wing structures.