Big Data Empowering Civil Aircraft Health Management: A Full-Cycle Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

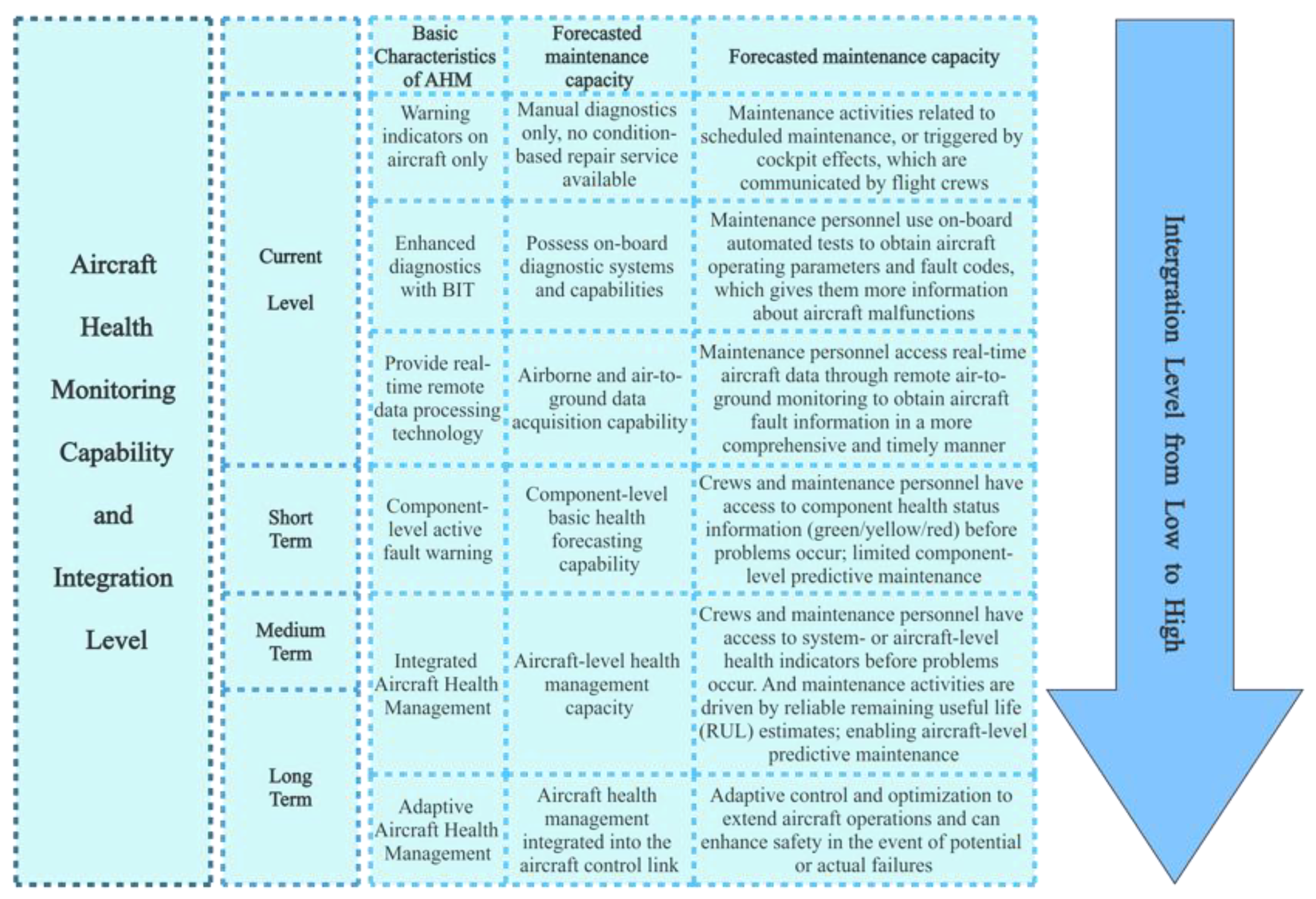

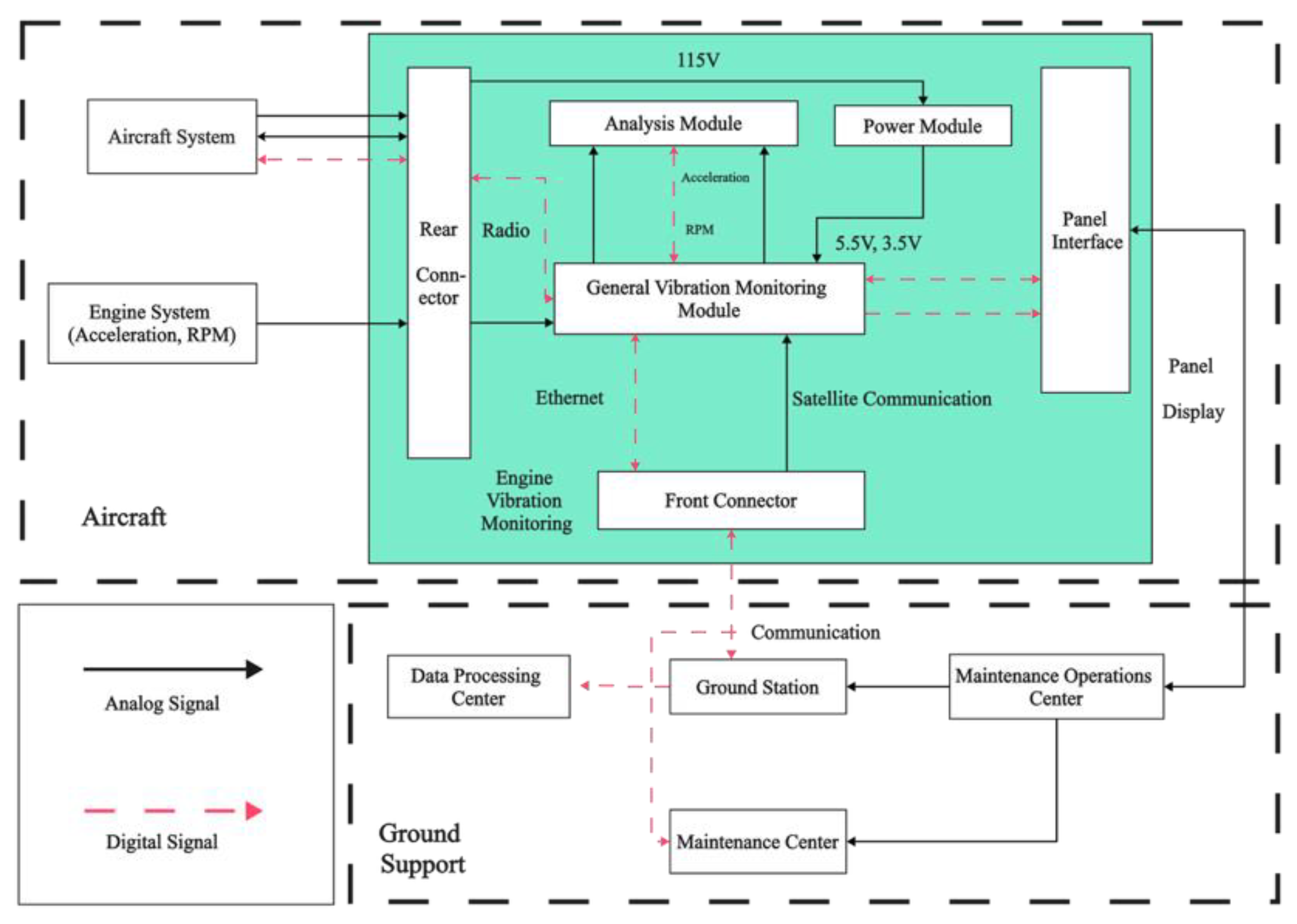

2. Current Status of Big Data Application in Civil Aircraft Intelligent Maintenance Field

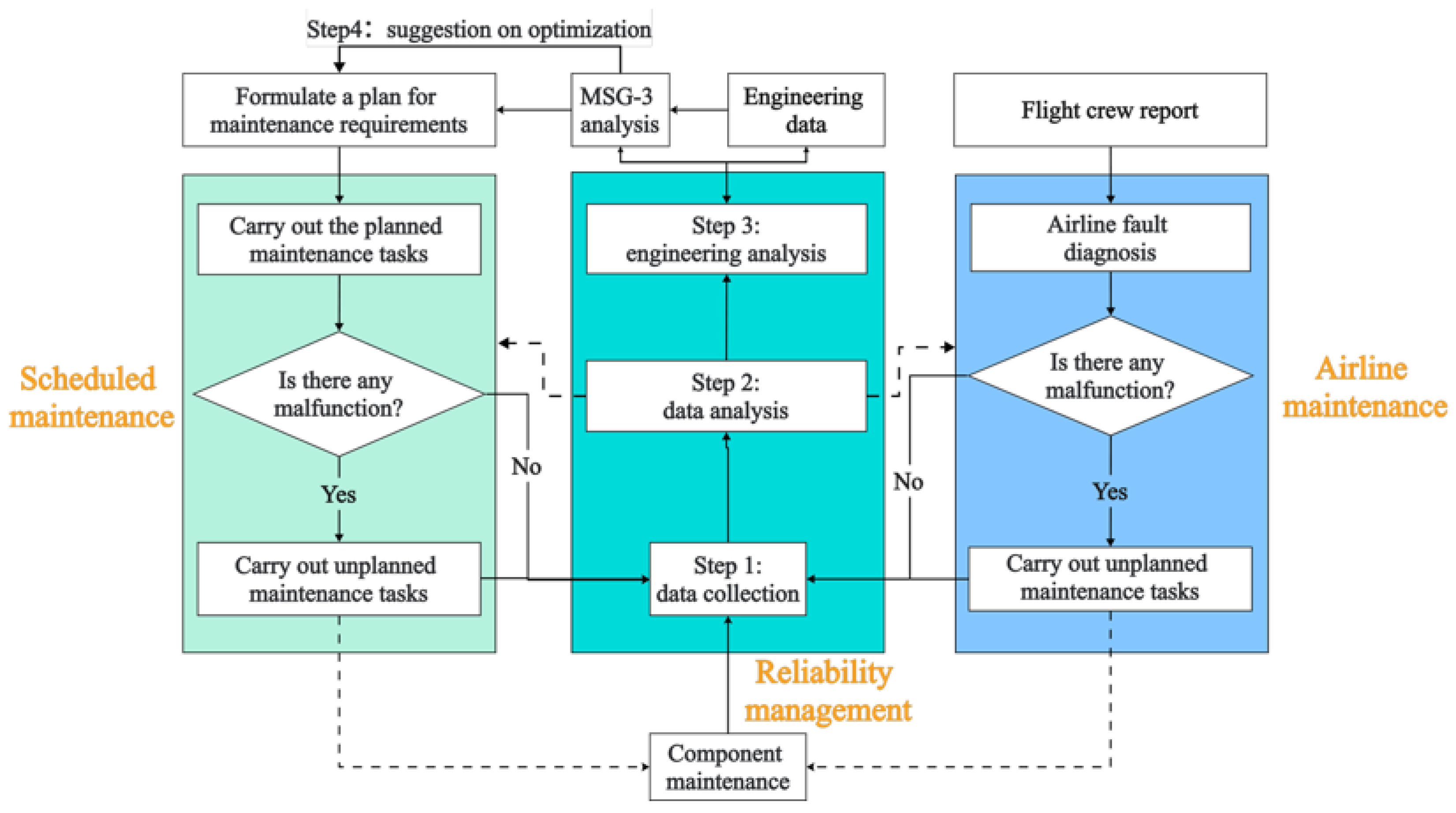

2.1. Maintenance Strategy Design Based on Data Analysis and Optimization Methods

2.1.1. Data-Driven Scheduled Maintenance Strategy

2.1.2. Maintenance Strategy Optimization via Statistical and Operational Research Methods

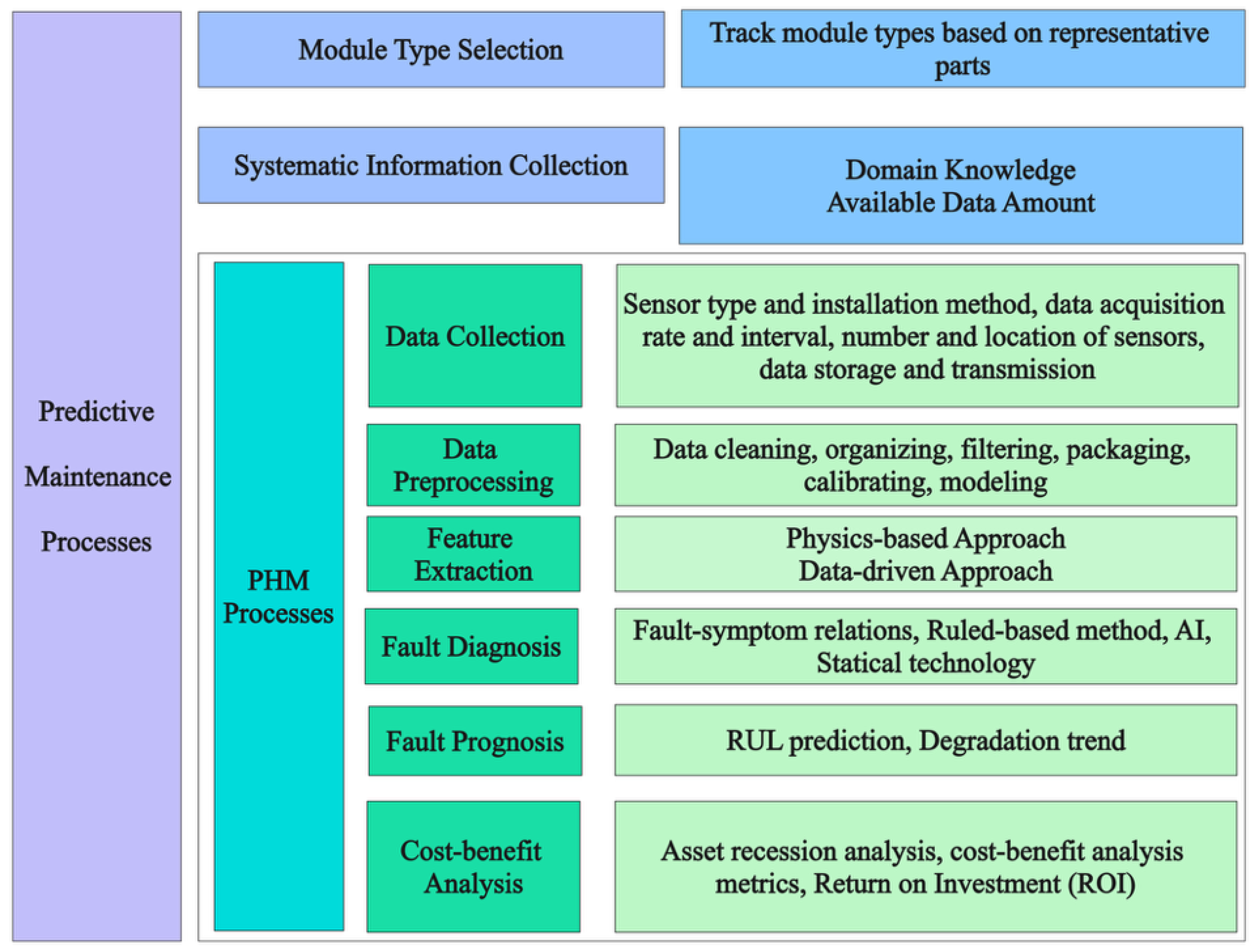

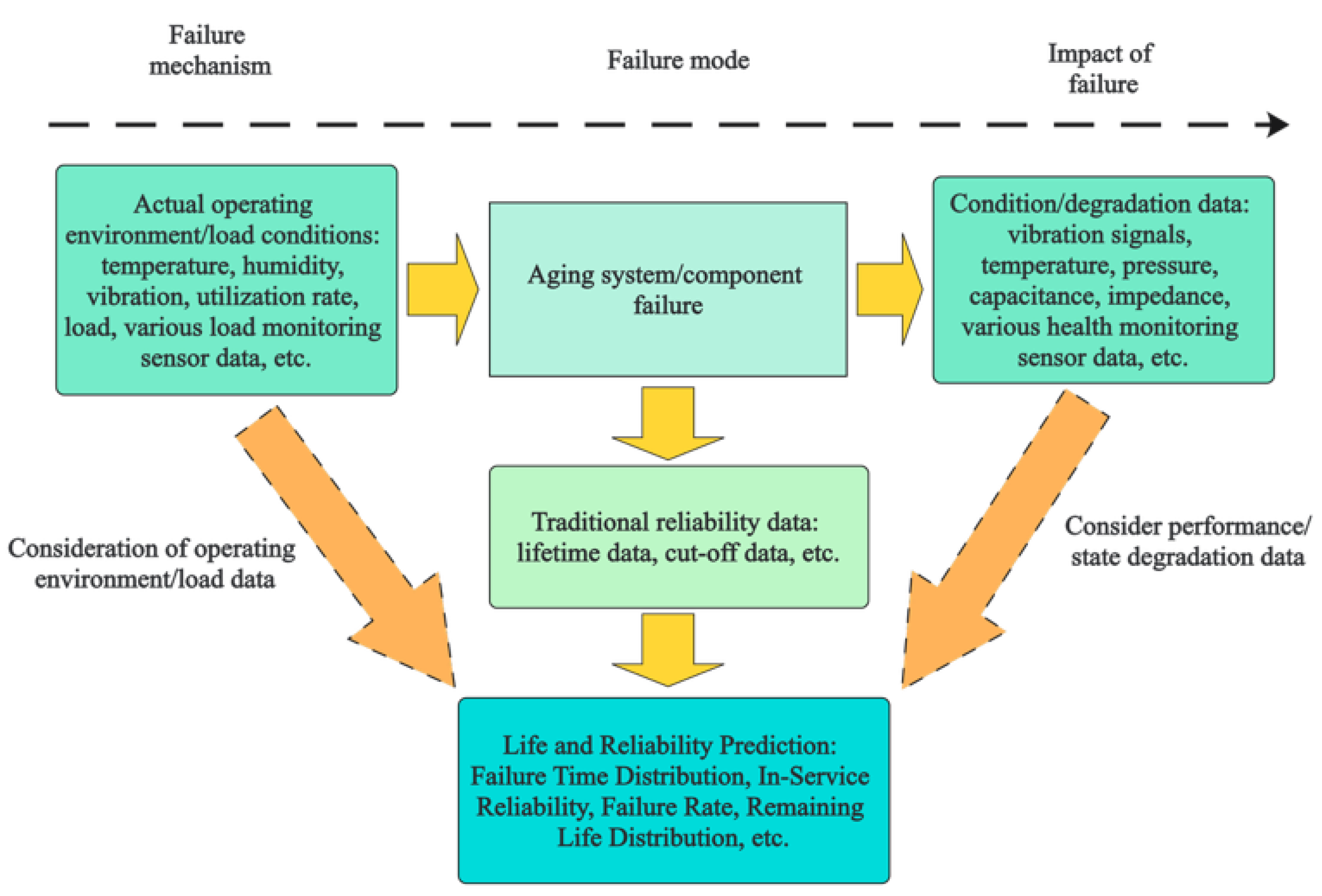

2.2. Big Data-Driven Real-Time Fault Diagnosis and Remaining Service Life Prediction Methods

2.2.1. Fault Diagnosis Methods Based on Real-Time Data

2.2.2. Fault Diagnosis and Prediction Supported by Quick Access Recorder Data

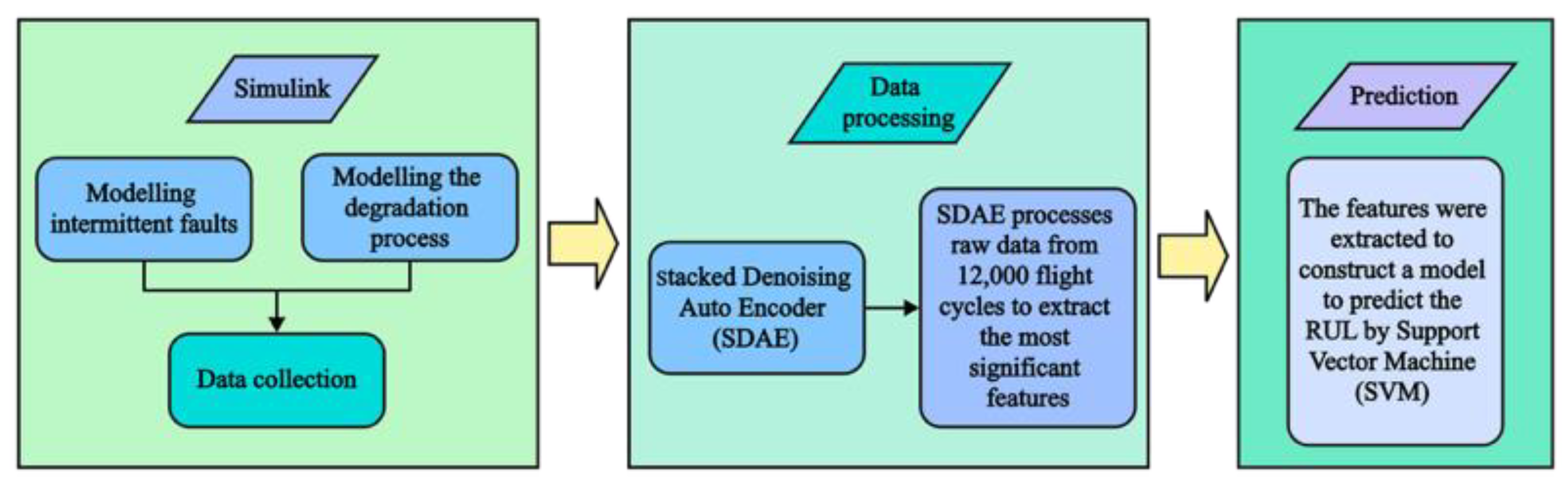

2.2.3. Data-Driven Remaining Useful Life Prediction Model and Application

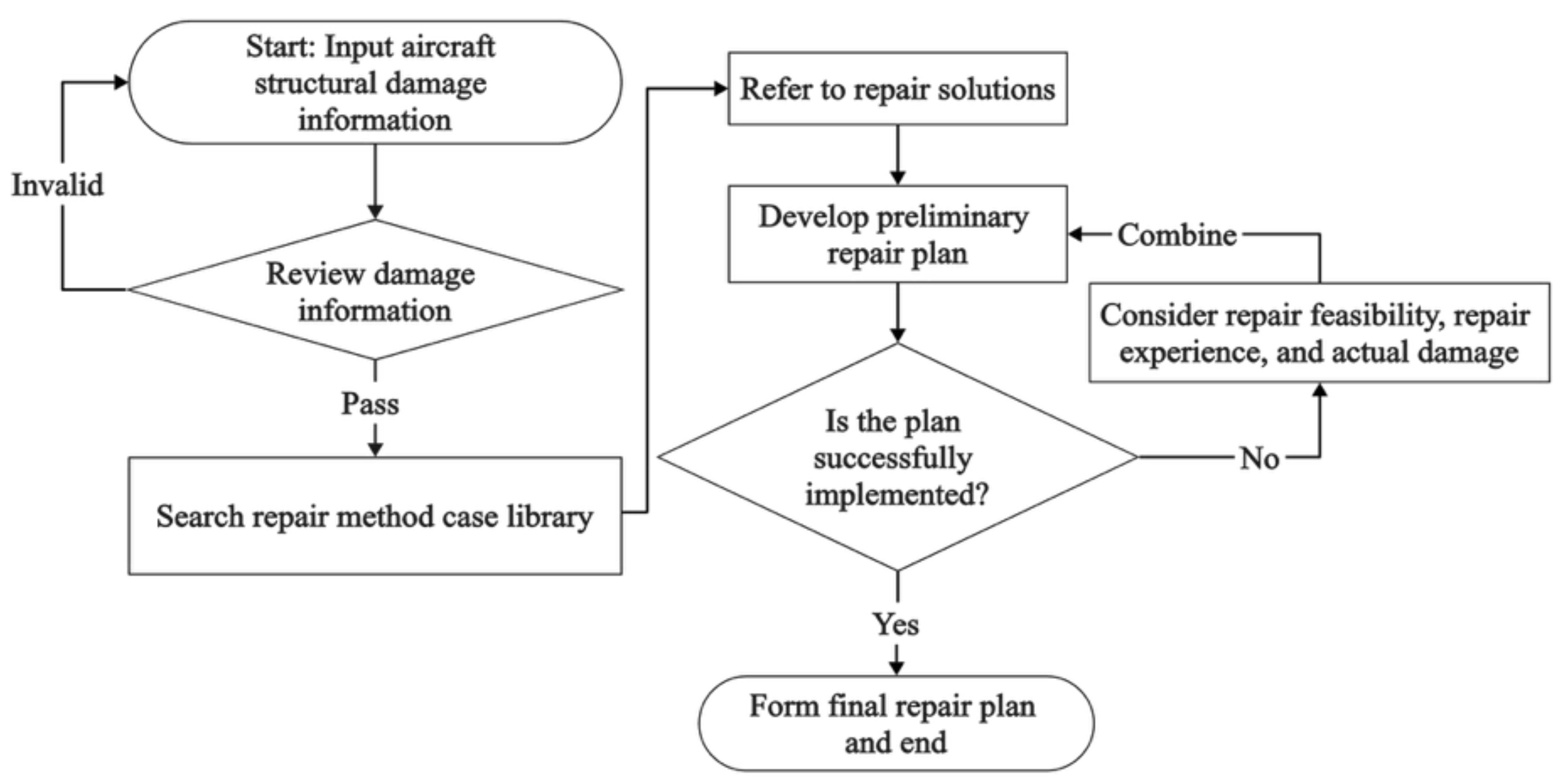

2.3. Corrective Maintenance Based on Massive Fault Data Information

2.3.1. Fault Data Detection Technology

2.3.2. Fault Information Extraction Techniques

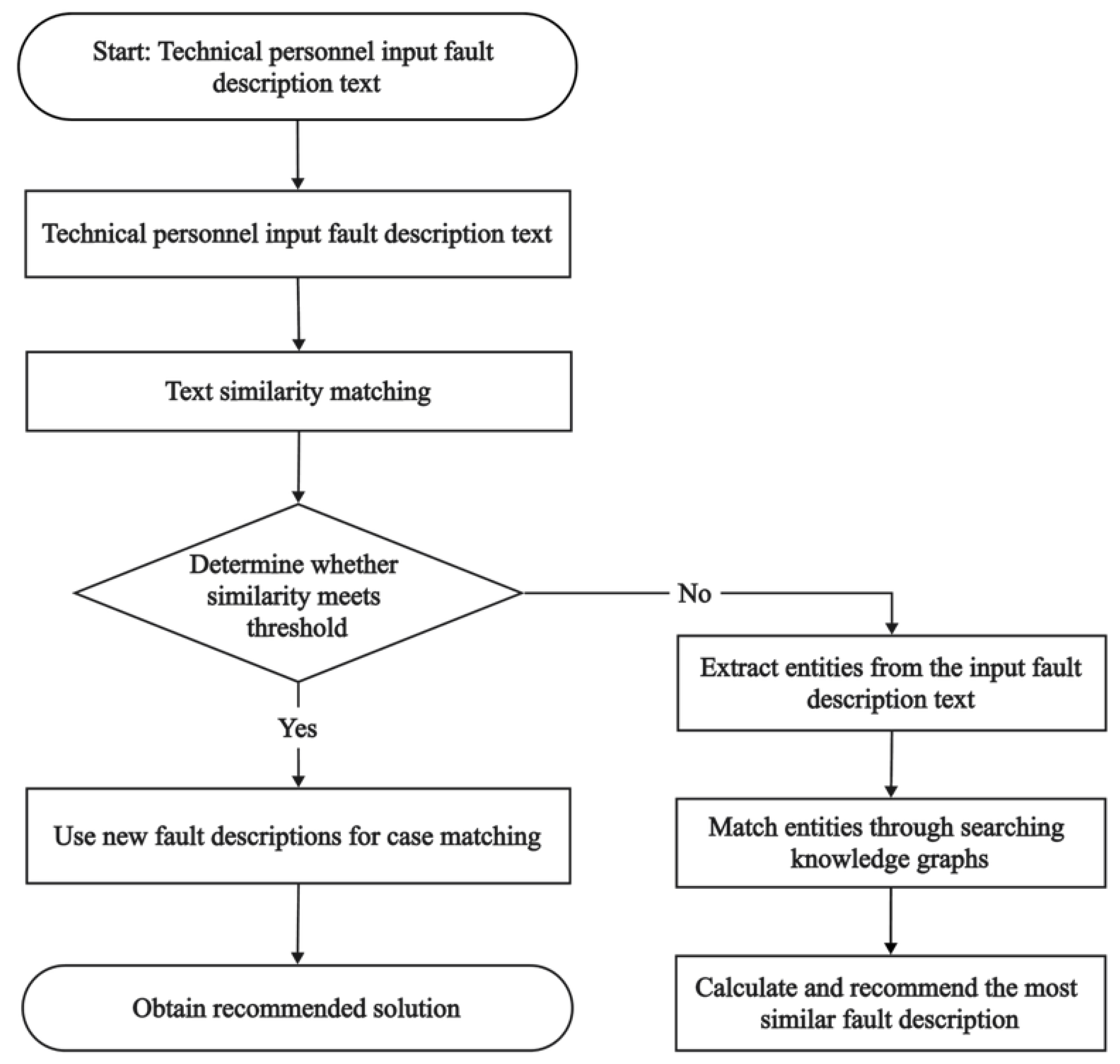

2.3.3. Constructing Knowledge Graph Based on Fault Data and Fault Information

3. Prospect of Big Data Application in the Field of Civil Aircraft Intelligent Maintenance

3.1. Maintenance Equipment and Platform Supported by Big Data Technology

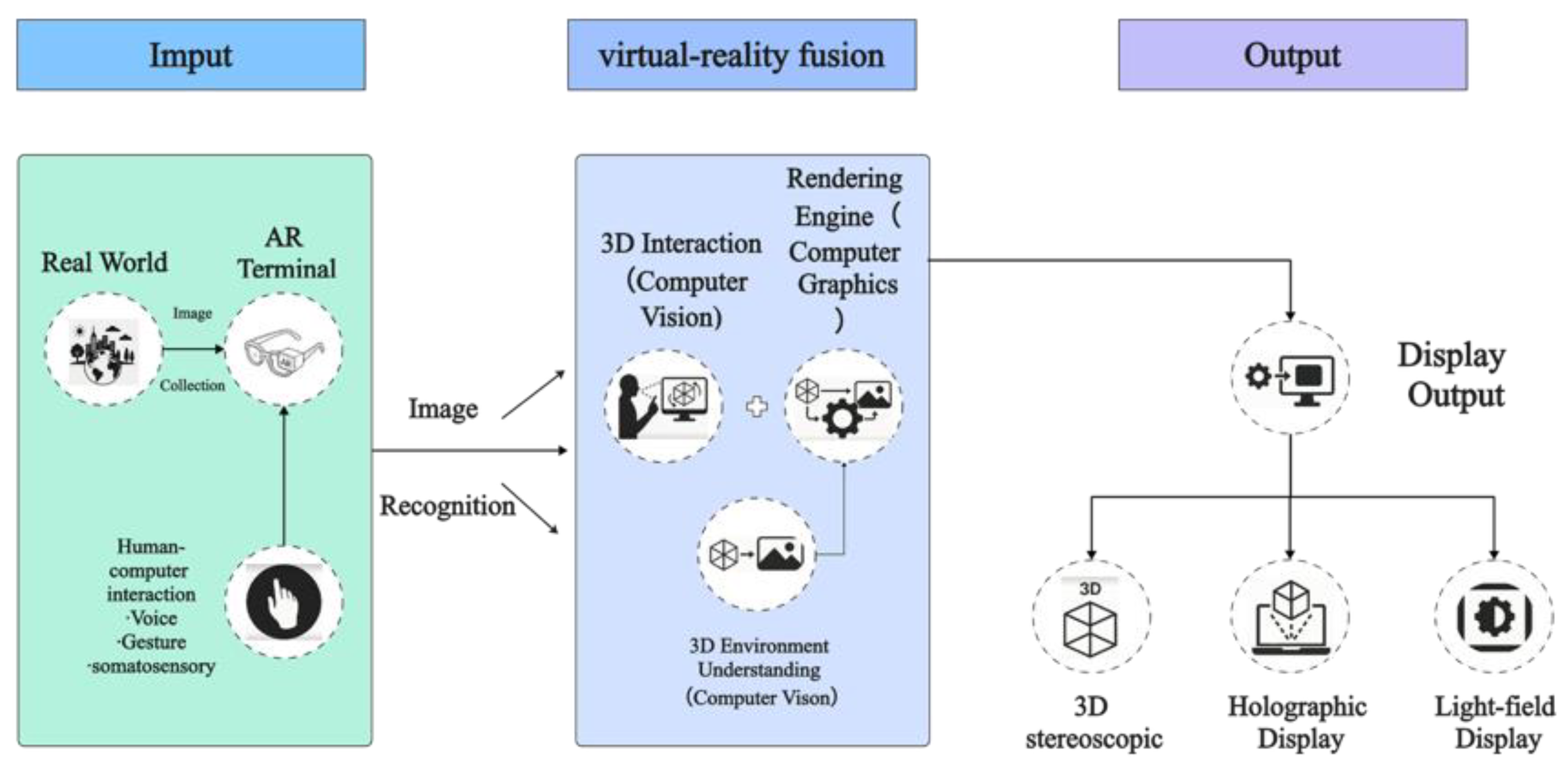

3.1.1. Augmented Reality Supported by Big Data

3.1.2. Data-Based Remote Support Platform for Civil Aviation Maintenance

3.1.3. Operation and Maintenance Assisted Decision Making Based on Image Data

4. Challenges and Potential Response Strategies for the Application of Big Data in the Field of Intelligent Maintenance of Civil Aircrafts

4.1. Big Language Modeling Enabled Intelligent Maintenance of Civil Aviation Aircraft

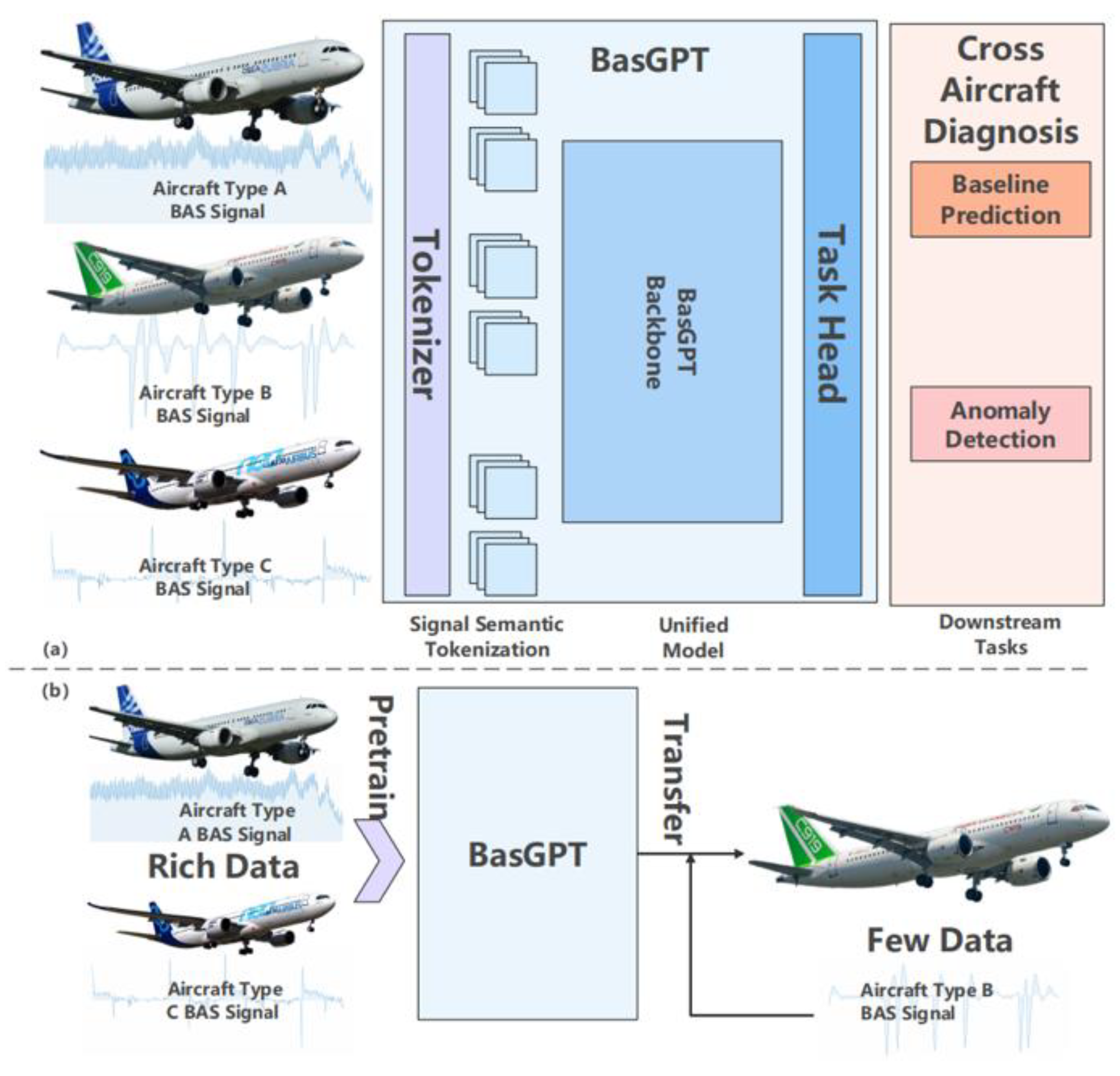

4.2. Potential Novel Artificial Intelligence Techniques in Civil Aviation Maintenance

4.3. Data Quality, Uncertainty, and Reliability Challenges in Data-Driven Aircraft Health Management

5. Discussion, Summary and Prospect

5.1. Discussion: Advantages, Constraints, and Practical Implications

5.2. Summary and Prospect

- Data-driven scheduled maintenance optimizes maintenance cycles and task allocation by analyzing real-time data and historical maintenance records, based on mathematical statistics and operations research theory.

- Real-time fault diagnosis relies on sensors and big data to monitor parameters and locate anomalies in real-time, supported by data analysis and machine learning to improve fault response speed.

- Predictive maintenance uses machine learning to warn of potential failures in advance, predict the RUL of components and systems, and reduce unplanned downtime.

- Data-driven corrective maintenance improves maintenance efficiency by summarizing after-action maintenance data, optimizing the repair process in combination with knowledge graph technology, and using intelligent maintenance equipment and platforms to assist in maintenance. Image recognition technology can also effectively detect the damage of civil aircraft by analyzing unstructured image data.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IVHM | Integrated Vehicle Health Management |

| CBM+ | Condition-Based Maintenance plus |

| HUMS | Health and usage monitoring system |

| CAW | Continuing Airworthiness |

| RUL | Remain useful life |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| MSG-3 | Maintenance steering group-3 |

| IMRBPB | International maintenance review board policy board |

| IP44 | Issue paper 44 |

| MRB | Maintenance review board |

| AHP | Analytic hierarchy process |

| PHM | Predictive and health management |

| UEVM | Universal engine vibration monitor |

| ARMA | Auto-regressive moving average |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| DAE | Deep auto encoder |

| DBN | Deep belief network |

| MCNN | Multiple channel convolutional neural network |

| DPM | Dynamic predictive maintenance |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| BP | Back propagation |

| RMBP | Random modified back propagation |

| QAR | Quick access recorder |

| ACARS | Aircraft communications addressing and reporting system |

| CNN | Convolutional neural networks |

| HDFS | Hadoop distributed file system |

| ADS | Aircraft detection system |

| PDM | Predictive maintenance |

| ECM | Expectation conditional maximization |

| SDAE | Stacked denoising autoencoder |

| IMA | Integrated modular avionics |

| KNN | K-nearest neighbors |

| LOF | Local outlier factor |

| CRF | Conditional random field |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional long short-term memory |

| BERT | Bidirectional encoder representations from transformers |

| BiGRU | Bidirectional gated recurrent unit |

| TF-IDF | Term frequency-inverse document frequency |

| BM | Boyer–Moore |

| BMEO | Beginning, Middle, End, Outside |

| NLR | Netherlands Aerospace Center |

| DNN | Deep neural networks |

| SSD | Single-shot detector |

| YOLO | You only look once |

| LLM | Large language model |

References

- NASA. Research and Technology Goals and Objectives for Integrated Vehicle Health Management (IVHM); NASA-CR-192656; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1992.

- Ezhilarasu, C.M.; Skaf, Z.; Jennions, I.K. The application of reasoning to aerospace Integrated Vehicle Health Management (IVHM): Challenges and opportunities. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2019, 105, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Defense (DoD). Condition-Based Maintenance Plus (CBM+) Guidebook (Updated Edition); Defense Acquisition University: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.dau.edu/sites/default/files/2024-08/CBM%2B%20Guidebook%20August%202024%20-%20Stamped.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- VAST. Health and Usage Monitoring Systems (HUMS) Toolkit; Vibration Analysis and Signal Processing Toolbox (VAST); International Helicopter Safety Team: Fairfax, VI, USA, 2013; Available online: https://vast.aero/archives/Toolkits/Toolkit_HUMS.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Part-M and Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC). EASA Regulations and Guidance Material 2023. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/acceptable-means-compliance-and-guidance-material-group/part-m-continuing-airworthiness (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- del Amo, I.F.; Erkoyuncu, J.A.; Roy, R.; Palmarini, R.; Onoufriou, D. A systematic review of Augmented Reality content-related techniques for knowledge transfer in maintenance applications. Comput. Ind. 2018, 103, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Jing, B.; Wang, S.; Pan, J.; Huang, Y.; Jiao, X. Fault Knowledge Graph Construction and Platform Development for Aircraft PHM. Sensors 2024, 24, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Tang, X.; Gu, S.; Cui, L. An intelligent guided troubleshooting method for aircraft based on HybirdRAG. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Yao, H.G.; Gu, Y.B.; Zhang, Y.Q. Optimization ideas of aircraft maintenance pro-gram based on digitization. Aviat. Maint. Eng. 2023, 139, 25–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.H.; Gui, H.; Jiang, H. Optimisation Guidelines for Civil Aircraft Maintenance Syllabus IMRBPB IP44 and Application Research. Aeronaut. Stand. Qual. 2018, 47, 42–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Air Transport Association. From Aircraft Health Monitoring to Aircraft Health Management. Available online: https://www.iata.org/contentassets/bf8ca67c8bcd4358b3d004b0d6d0916f/ahm-wp-2nded-2023.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Delta TechOps. Delta TechOps Expanding Predictive Maintenance Capabilities with New Airbus Partnership. Available online: https://deltatechops.com/delta-techops-expanding-predictive-maintenance-capabilities-with-new-airbus-partnership/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Ahsan, S.; Lemma, T.; Gebremariam, M. Reliability analysis of gas turbine engine by means of bathtub- shaped failure rate distribution. Process Saf. Prog. 2020, 39, E12115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudholkar, G.S.; Asubonteng, K.O.; Hutson, A.D. Transformation of the bathtub failure rate data in reliability for using Weibull-model analysis. Stat. Methodol. 2009, 6, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonge, B. Discretizing continuous-time continuous-state deterioration processes, with an application to con-dition-based maintenance optimization. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 188, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Weide, T.; Deng, Q.; Santos, B.F. Robust long-term aircraft heavy maintenance check scheduling optimization under uncertainty. Comput. Oper. Res. 2022, 141, 105667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Jang, Q.; Zhou, Y. Schedule maintenance task interval optimization method based on in-service da-ta. Adv. Aeronaut. Sci. Eng. 2020, 11, 572–576. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ying, S.Q. Research on Optimization Method of Civil Aircraft Maintenance Interval Based on Reliability Data. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sriram, C.; Haghani, A. An optimization model for aircraft maintenance scheduling and re-assignment. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2003, 37, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozanidis, G.; Liberopoulos, G.; Pitsilkas, C. Flight and maintenance planning of military aircraft for maximum fleet availability. Mil. Oper. Res. 2010, 15, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moudani, W.; Mora-Camino, F. A dynamic approach for aircraft assignment and maintenance scheduling by airlines. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2000, 6, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başdere, M.; Bilge, Ü. Operational aircraft maintenance routing problem with remaining time consideration. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 235, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Santos, B.F.; Verhagen, W.J. A novel decision support system for optimizing aircraft maintenance check schedule and task allocation. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 146, 113545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Liu, Y.; Lu, X.; Tong, S. Model of determination maintenance intervals of aircraft structural with low utilization. Acta Aeronaut. Et Astronaut. Sin. 2018, 39, 221516. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, N.; Coit, D.W.; Song, S.; Feng, Q. Optimization of on condition thresholds for a system of degrading components with competing dependent failure processes. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 192, 106547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, N.; Tsianikas, S.; Coit, D.W. Dynamic maintenance model for a repairable multicomponent system using deep reinforcement learning. Qual. Eng. 2022, 34, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, N.; Tsianikas, S.; Coit, D.W. Reinforcement earning for dynamic condition based maintenance of a system with individually repairable components. Qual. Eng. 2020, 32, 388–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pater, I.; Reijns, A.; Mitici, M. Alarm-based predictive maintenance scheduling for aircraft engines with im-perfect Remaining Useful Life prognostics. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 221, 108341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongsheng, Y. Research on Maintenance Optimization Method and Key Technology of Civil Aircraft Based on Operation Data. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Walter, G.; Flapper, S.D. Condition-based maintenance for complex systems based on current component status and Bayesian updating of component reliability. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 168, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Santos, B.E. A stochastic aircraft maintenance and crew scheduling problem with multiple check types and aircraft avail ability constraints. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 299, 814–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzén, M.; Bandaru, S.; Ng, A.H.C. Digital-twin-based decision support of dynamic maintenance task prioriti-zation using simulation-based optimization and genetic programming. Decis. Anal. J. 2022, 3, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodieci, A.; Caricato, A.; Carlucci, A.P.; Ficarella, A.; Mainetti, L.; Vergallo, C. Using different machine learning approaches to evaluate perfor-mance on spare parts request for aircraft engines//E3S Web of Conferences. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 197, 11014. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, T.; Kim, N.H. Cost-Effectiveness of Structural Health Monitoring in Fuselage Maintenance of the Civil Aviation Industry. Aerospace 2018, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, W.J.C.; Santos, B.F.; Freeman, F.; van Kessel, P.; Zarouchas, D.; Loutas, T.; Yeun, R.C.K.; Heiets, I. Condition-Based Maintenance in Aviation: Challenges and Opportunities. Aerospace 2023, 10, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarin, P.; Macchi, M.; Roda, I.; Sala, G.; Baldi, A.; Airoldi, A. Economic impact assessment of structural health monitoring systems on helicopter blade beginning of life. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2024, 2024, 2865576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Mitici, M.; Blom, H.A.P.; Bieber, P.; Freeman, F. Analyzing Emerging Challenges for Data-Driven Predictive Aircraft Maintenance Using Agent-Based Modeling and Hazard Identification. Aerospace 2023, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, P.; Rao, H.G.; Buderath, M. Machine learning based data driven diagnostics & prognostics framework for aircraft predictive maintenance. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on NDT in Aerospace, Dresden, Germany, 24–26 October 2018; pp. 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, O.; Wang, Q.; Svensen, M.; Dersin, P.; Lee, W.J.; Ducoffe, M. Potential, challenges and future directions for deep learning in prognostics and health management applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 92, 103678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basora, L.; Bry, P.; Olive, X.; Freeman, F. Aircraft Fleet Health Monitoring with Anomaly Detection Techniques. Aerospace 2021, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangut, M.D.; Jennions, I.K.; King, S.; Skaf, Z. A rare failure detection model for aircraft predictive maintenance using a deep hybrid learning approach. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 2991–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.A.O.; Zhang, Y.; Jianfei, F.E.N.G. Failure rate analysis and maintenance plan optimization method for civil aircraft parts based on data fusion. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103219. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, D.; Boyacı, B.; Zografos, K. An optimisation framework for airline fleet maintenance scheduling with tail assignment considerations. Trans. Res. B Methodol. 2019, 133, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chan, F.T.; Chung, S.H.; Niu, B.; Qu, T. A two-stage optimization approach for aircraft hangar maintenance planning and staff assignment problems under MRO outsourcing mode. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 146, 106607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseremoglou, I.; van Kessel, P.J.; Santos, B.F. A Comparative Study of Optimization Models for Condition-Based Maintenance Scheduling of an Aircraft Fleet. Aerospace 2023, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, J.; Sanchez de Leon, L.; Montañes, J.L.; Vega, J.M. A Reduced Order Model for Monitoring Aeroengines Condition in Real Time. Aerospace 2023, 10, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Avdelidis, N.P. Prognostic and Health Management of Critical Aircraft Systems and Components: An Overview. Sensors 2023, 23, 8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molęda, M.; Małysiak-Mrozek, B.; Ding, W.; Sunderam, V.; Mrozek, D. From Corrective to Predictive Maintenance—A Review of Maintenance Approaches for the Power Industry. Sensors 2023, 23, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Yu, D.S.; Ding, K.Y.; Liu, P.P. Research and application trends of predictive techniques in aircraft maintenance. Prog. Aeronaut. Eng. 2021, 12, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Yan, H.; Li, Z.; Duan, S.; Hu, H.; Zuo, H. Research advances in aircraft predictive maintenance. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2025, 46, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Huang, J.Q.; Zhou, J.; Chen, X.F.; Lu, F.; Wei, F. Current status, challenges and opportunities of civil aero-engine diagnostics & health management Ⅰ: Diagnosis and prognosis of engine gas path, mechanical and FADEC. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2022, 43, 9–41. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, I.; Munir, K.; Ikram, A.; El-Bakry, M. Predictive maintenance analytics and implementation for aircraft: Challenges and opportunities. Syst. Eng. 2023, 26, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llasag Rosero, R.; Silva, C.; Ribeiro, B. Remaining Useful Life Estimation of Cooling Units via Time-Frequency Health Indicators with Machine Learning. Aerospace 2022, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulansky, V.; Raza, A. Predictive maintenance: A historical survey of models with imperfect inspections. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 268, 111939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabashkin, I.; Fedorov, R.; Perekrestov, V. Decision-Making Framework for Aviation Safety in Predictive Maintenance Strategies. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Wang, P.; Zuo, H.F.; Zeng, H.; Sun, J.; Yang, W.; Wei, F.; Chen, X. Current status, challenges and opportunities of civil aero-engine diagnostics & health management Ⅱ: Comprehensive off-board diagnosis, life management and intelligent condition based MRO. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2022, 43, 34–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lima Lopes, L.; Travé-Massuyès, L.; Jauberthie, C.; Alcalay, G. A review of fault diagnosis techniques applied to aircraft air data sensors. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Principles of Diagnosis and Resilient Systems (DX 2024), Schloss Dagstuhl, Vienna, Austria, 4–7 November 2024; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ranasinghe, K.; Sabatini, R.; Gardi, A.; Bijjahalli, S.; Kapoor, R.; Fahey, T.; Thangavel, K. Advances in Integrated System Health Management for mission-essential and safety-critical aerospace applications. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2022, 128, 100758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G. Aviation PHM system research framework based on PHM big data center. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management (ICPHM), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 20–22 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Land, J.E. HUMS-the benefits-past, present and future. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings, Big Sky, MT, USA, 10–17 March 2001; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 3083–3094. [Google Scholar]

- GEGGITT. Engine Health and Vibration Monitoring. 2023. Available online: https://www.meggitt.com/products-services/engine-health-and-vibration-monitoring/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Çınar, Z.M.; Abdussalam Nuhu, A.; Zeeshan, Q.; Korhan, O.; Asmael, M.; Safaei, B. Machine learning in predictive maintenance towards sustainable smart manufacturing in industry 4.0. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roadmap, A.I. A Human-Centric Approach to AI in Aviation; European Aviation Safety Agency: Cologne, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karaoğlu, U.; Mbah, O.; Zeeshan, Q. Applications of machine learning in aircraft maintenance. J. Eng. Manag. Syst. Eng. 2023, 2, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

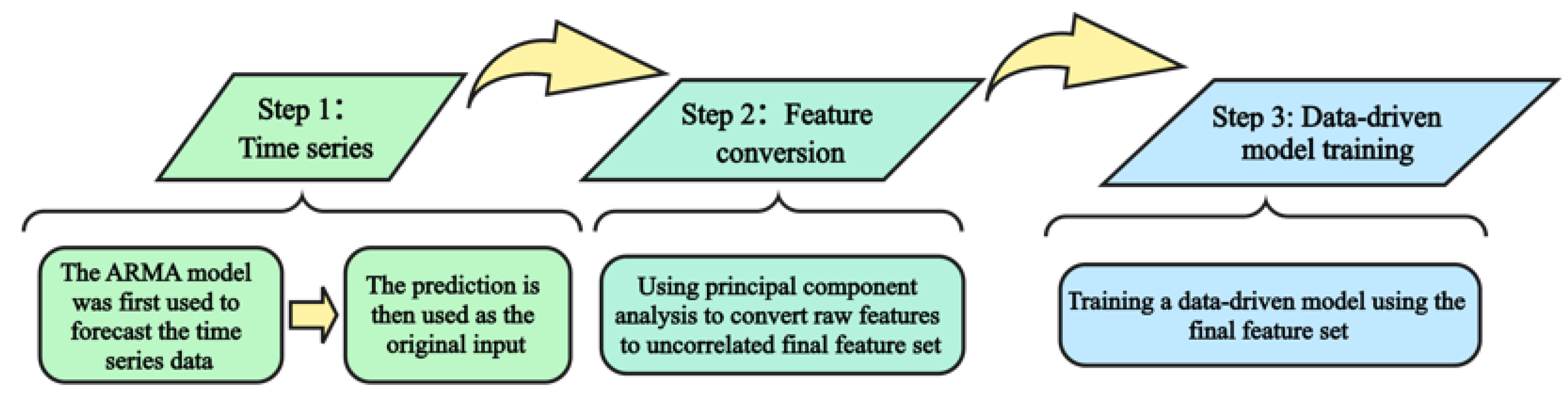

- Baptista, M.; Sankararaman, S.; De Medeiros, I.P.; Nascimento, C., Jr.; Prendinger, H.; Henriques, E.M. Forecasting fault events for predictive maintenance using data-driven techniques and ARMA modeling. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 115, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. Research of Fault Diagnosis and Safety Forecast of Civil Aircraft Based on Big Bata. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.M.; Ren, P.; Huang, Y.X. Baseline Equation Fitting of Aeroengine. Mech. Eng. Autom. 2016, 45, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.L.; Luo, L.X.; Qu, C.G.; Kang, L.P. Study of the surge fault diagnosis of an aeroengine based on the LS-SVM (Least Square-Supporting Vector Machine). J. Eng. Therm. Energy Power 2013, 28, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

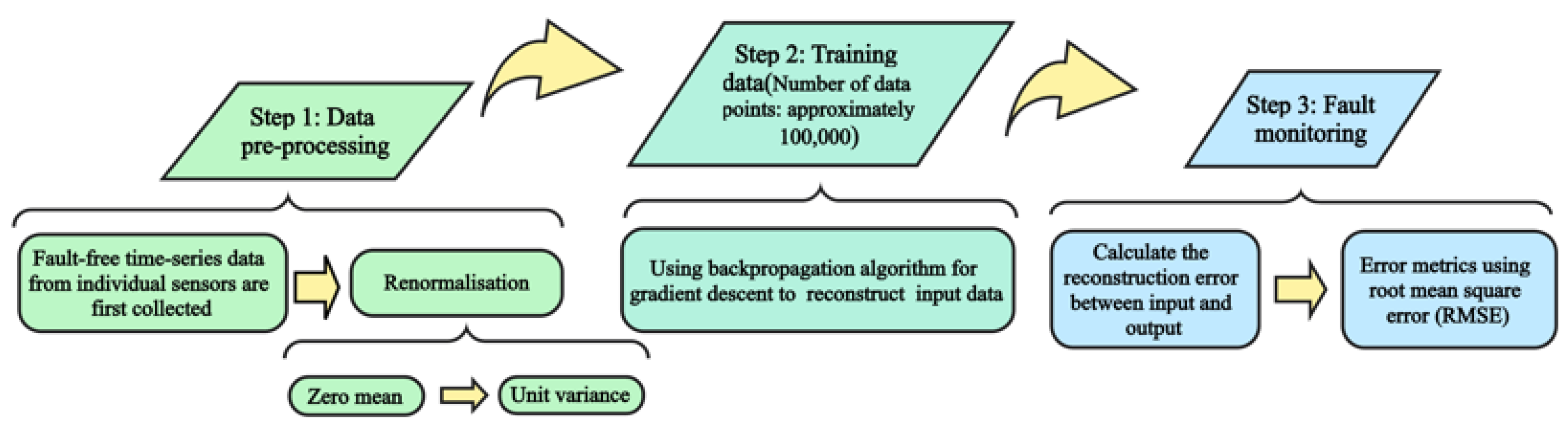

- Reddy, K.K.; Sarkar, S.; Venugopalan, V.; Giering, M. Anomaly detection and fault disambiguation in large flight data: A multi-modal deep auto-encoder approach. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the PHM Society, Denver, CO, USA, 2–6 October 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P. Commercialization of prognostics systems leveraging commercial off-the-shelf instrumentation, analysis, and data base technologies. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the PHM Society 2011, Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–29 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Dong, E.; Wang, R.; Li, S.; Han, Y. Research progress and development trend of prognostics and health management key technologies for equipment diesel engine. Processes 2023, 11, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, F.; Regattieri, A.; Bortolini, M.; Gamberi, M.; Pilati, F. Predictive Maintenance: A Novel Framework for a Data-Driven, Semi-Supervised, and Partially Online Prognostic Health Management Application in Industries. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabashkin, I.; Perekrestov, V. Ecosystem of aviation maintenance: Transition from aircraft health monitoring to health management based on IoT and AI synergy. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Zhong, S.S.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Y.J. Gas turbine fault diagnosis method under small sample based on transfer learning. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 27, 3450–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.S.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.J. Fault diagnosis of civil aero-engine driven by unbalanced samples based on DBN. J. Aerosp. Power 2019, 34, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngui, W.K.; Leong, M.S.; Shapiai, M.I.; Lim, M.H. Blade fault diagnosis using artificial neural network. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2017, 12, 519–526. [Google Scholar]

- Keng, N.W.; Leong, M.S.; Shapiai, M.I.; Hee, L.M. Blade fault localization with the use of vibration signals through artificial neural network: A data-driven approach. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 31, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H.; Lu, S.D.; Hsieh, C.C.; Hung, C.C. Fault detection of wind turbine blades using multi-channel CNN. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

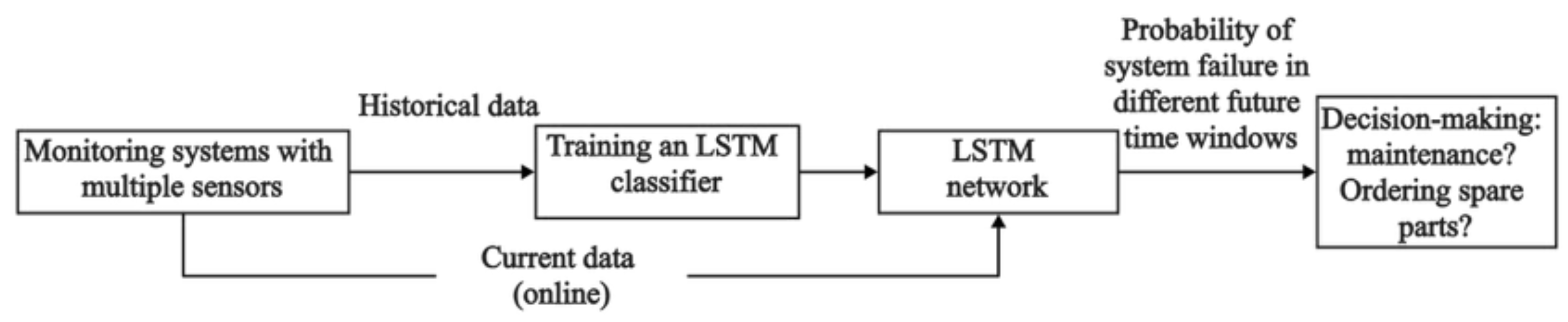

- Nguyen, K.T.; Medjaher, K. A new dynamic predictive maintenance framework using deep learning for failure prognostics. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 188, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Selesnick, I.; Cai, G.; Feng, Y.; Sui, X.; Chen, X. Nonconvex sparse regularization and convex optimization for bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 7332–7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Liu, Z.; Yi, S. Intelligent diagnosis of aircraft electrical faults based on rmbp neural network. J. Syst. Simul. 2019, 30, 3493–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.Y.; Jiang, C.Y.; Lu, M.W.; Ye, C.; Li, S. Fault diagnosis of aircraft landing gear hydraulic system based on TSFFCNN-PSO-SVM. J. Aerosp. Power 2024, 39, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.X.; Liu, Y.Y.; Huang, J.Y.; Chen, X. Fault Diagnosis of Landing Gear System Based on Bayesian Network Inference. Comput. Meas. Control. 2016, 24, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarselli, G.; Nicassio, F. Machine Learning for Structural Health Monitoring of Aerospace Structures: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ma, R.; Zou, C.Z.; Wang, Z.Y. ACARS data protection technology based on national secret algorithm. J. Inform. Secur. Res. 2021, 7, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.L.; Gao, Y. Research on QAR data knowledge and application in civil aviation field. Mech. Eng. Autom. 2018, 47, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanff, E.; Feldman, K.; Ghelam, S.; Sandborn, P.; Glade, M.; Foucher, B. Life cycle cost impact of using prognostic health management (PHM) for helicopter avionics. Microelectron. Reliab. 2007, 47, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.G.; Han, P.P.; Wu, R.B. QAR data processing based on data mining. Inform. Electron. Eng. 2012, 10, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

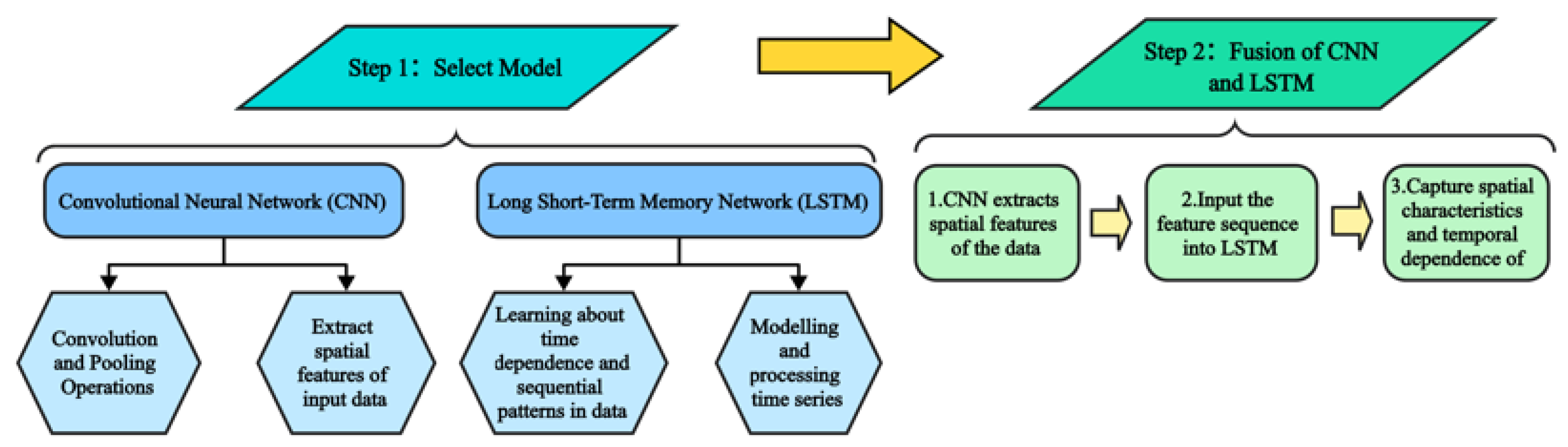

- Zhang, P.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.N.; Fan, Z.Y.; Duan, Z.B. Feature extraction and prediction of QAR data based on CNN-LSTM. Appl. Res. Comput. 2019, 36, 2958–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, T.X.; Li, R.; Xiong, Y.; Fang, H.Z. Civil aircraft fault prediction and verification based on QAR data. Comput. Meas. Control 2019, 27, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Zhang, C.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q. Data evidence-based aircraft continuing airworthiness management assistant system and applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 4th International Conference on Civil Aviation Safety and Information Technology (ICCASIT), Dali, China, 12–14 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 579–586. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.X.; Jiang, C.S.; Ma, C. Vibration fault analysis of low pressure rotor of civil aero-engine based on ARIMA model. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2019, 19, 362–368. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. Research on QAR Data Mining Algorithm Based on Grey System Theory; Civil Aviation University of China: Tianjin, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zuo, H.; Sun, J.; Liu, Z. Research on on-line monitoring method of lubricating oil consumption rate of aeroengine based on QAR data. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Sensing, Diagnostics, Prognostics, and Control (SDPC), Shanghai, China, 16–18 August 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.L.; Yang, L.; Lin, Y.S.; Luo, L.; Qu, C. Aero-engine anomaly detection using support vector regression. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aerosp. Eng. 2013, 32, 1616–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Research on Key Techniques of Real-Time Monitoring for Aircraft Flight Safety; Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Nanjing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, K.; Zuo, H.F.; Sun, J.Z.; Li, H.Y.; Ding, X.; Liu, R.C.; Wang, R.H. QAR data health monitoring method of civil aircraft bleed air system. J. Mech. Eng. 2015, 51, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.N. The Research of Health Assessment and Fault Diagnosis Method of Civil Aircraft Flight Control System; Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Nanjing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Memarzadeh, M.; Matthews, B.; Avrekh, I. Unsupervised anomaly detection in flight data using convolutional variational auto-encoder. Aerospace 2020, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.W.; Mo, L.P.; Wang, Y.S.; Yin, K.; Zhao, Q.; Qing, X.L. Aero-engine status identification based on full-segment QAR data and convolutional neural network. J. Aerosp. Power 2021, 36, 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.G.; Li, J.L.; Wang, H.F. Civil aircraft long touchdown exceedance detection based on autoencoder and HMM. J. Beijing Univ. 2022, 48, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.B.; Du, H.L.; Zhang, P. Feature extraction of QAR data based on QAR2Vec model. China Saf. Sci. J. 2021, 31, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.Q.; Li, N.; Liu, K.L.; Fu, Z.Z.; Ji, P.F.; Zhang, S.L.; Dong, L.W.; Sun, Y.T. Damage state evaluation method of service turbine blades based on MAML-LSTM. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin 2024, 45, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

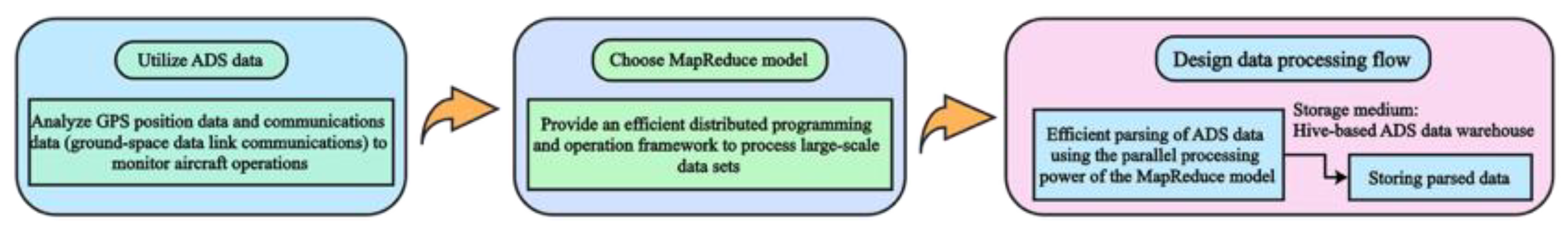

- Feng, X.J.; Wu, X.Y.; Zhao, J.; He, Y.; Fang, S. Construction of QAR data warehouse in Hive. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2017, 53, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.J.; Liu, F. ADS-B data parsing and storage method based on Hadoop. Aerosp. Control. 2017, 35, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Y. A LSTM and Cost-Sensitive Learning-Based Real-Time Warning for Civil Aviation Over-limit. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Sensors, Electronics and Computer Engineering (ICSECE), Jinzhou, China, 29 October–1 November 2023; pp. 550–556. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Hu, C.H.; Ren, Z.Q.; Xiong, W. Performance deoradation modelino and remainino useful lifte orediction foaero-engine based on nonlinear Wiener process. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2020, 41, 223291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ding, Q.; Sun, J.Q. Remaining useful life estimation in prognostics using deep convolution neural networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 172, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Ma, C.; Luo, Y. Rul prediction for IMA based on deep regression method. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 10th International Workshop on Computational Intelligence and Applications (IWCIA), Hiroshima, Japan, 11–12 November 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, D.; Ribeiro, B.; Cardoso, A. Web-based tool for predicting the Remaining Useful Lifetime of Aircraft Components. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th Experiment International Conference, Funchal, Portugal, 12–14 June 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 231–232. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Yu, J.; Siegel, D.; Lee, J. A similarity-based prognostics approach for remaining useful life estimation of engineered systems. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management, Denver, CO, USA, 6–9 October 2008; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kabashkin, I. The Iceberg Model for Integrated Aircraft Health Monitoring Based on AI, Blockchain, and Data Analytics. Electronics 2024, 13, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, X.; Luo, S.; Song, M.; Li, W. Towards Domain-Specific Knowledge Graph Construction for Flight Control Aided Maintenance. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Yang, W. Knowledge Graph Construction Method for Commercial Aircraft Fault Diagnosis Based on Logic Diagram Model. Aerospace 2024, 11, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basora, L.; Olive, X.; Dubot, T. Recent Advances in Anomaly Detection Methods Applied to Aviation. Aerospace 2019, 6, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.Z.; Qu, J.L.; Yuan, T.; Gao, F.; Fu, Z. Flight data novelty detection method based on improved SVDD. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2014, 35, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, S.; Huo, L.; Wang, L.; Lu, W. Anomaly detection method for flight data based on cluster analysis. In Proceedings of the 2015 Aeronautical Experiment and Test Technology Academic Exchange Conference, Measurement and Control Technology Editorial Board, Cairns, Australia, 25–27 November 2015; Society of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X. Spacecraft anomaly detection method based on regression analysis. J. Telem. Track. Command 2022, 43, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasra, S.K.; Valentino, G.; Muscat, A.; Camilleri, R. Hybrid machine learning-statistical method for anomaly detection in flight data. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Sun, Y.Z.; Wu, H.L. Information extraction for aircraft fault text. Comput. Mod. 2024, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collobert, R.; Weston, J.; Bottou, L.; Karlen, M.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Kuksa, P. Natural language processing (almost) from scratch. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2493–2537. Available online: http://jmlr.org/papers/v12/collobert11a.html (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Qi, Y.D.; Ding, H.Q.; Wu, J.Y.; Si, W. Military Named Entity Identification Method Combining Ontology and BiLSTM-CRF. J. Ordnance Equip. Eng. 2020, 41, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Chen, M.M.; Wang, H.J.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, A. Chinese named entity recognition method based on ALBERT-BGRU-CRF. Comput. Eng. 2022, 48, 89–94, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, H.; Li, H.F. Research of relationship extraction method of civil aviation emergency domain ontology. J. Front. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Huang, H.S.; Yao, L.G. Entity extraction for aero-engine fault knowledge graph. Modular Mach. Tool Automat. Manuf. Tech. 2021, 63, 69–73, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.G.; Liu, K.N.; Wang, S. Fault knowledge graph construction for aviation equipment based on BiGRU-Attention improvement. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2024, 45, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, C.; Tang, X.L.; Shaolin, F. A method of recognizing aero-engine fault entity and its application. J. Air Force Eng. Univ. 2022, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.Q.; Ding, Y.T.; Xia, T.B.; Pan, E.S.; Xi, L.F. Integrated modeling of commercial aircraft maintenance plan recommendation system based on knowledge graph. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 2023, 57, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L.; Wang, Y.W.; Ding, C.; Chen, H. The design and realization of aircraft maintenance and repair’s knowledge system based on knowledge graph. Intern. Combust. Engine Parts 2019, 40, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, T.; Zeng, J.; Cheng, Y.; Liang, M. Knowledge graph construction technology and its application in aircraft power system fault diagnosis. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2022, 43, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, J.; Wu, T.; Liu, J. Information Extraction of Aviation Accident Causation Knowledge Graph: An LLM-Based Approach. Electronics 2024, 13, 3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, X. MBJELEL: An end-to-end knowledge graph entity linking method applied to civil aviation emergencies. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, T.A.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Abdullah, H.B.; Jan, S.; Namoun, A.; Alzahrani, A.; Nadeem, A.; Alkhodre, A.B. In-Depth Review of Augmented Reality: Tracking Technologies, Development Tools, AR Displays, Collaborative AR, and Security Concerns. Sensors 2023, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Xu, F.; Liu, J.; Dai, Z.; Zhou, W.; Li, S.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, H. Holographic Three-Dimensional Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality Display Based on 4K-Spatial Light Modulators. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, P.A.; Simon, A. The good news, the bad news, and the ugly truth: A review on the 3D interaction of light field displays. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Chen, M.Y.; Shan, Q.; Sun, L.M. Application of AR technology in virtual maintenance of aircraft parts. Logist. Sci. Tech. 2021, 44, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ceruti, A.; Liverani, A.; Marzocca, P. A 3D user and maintenance manual for UAVs and commercial aircrafts based on augmented reality. In Proceedings of the SAE 2015 AeroTech Congress & Exhibition, Seattle, WA, USA, 22–24 September 2015; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, T.; Bischof, J.; Geyman, M.; Lise, E. Reducing maintenance error with wearable technology. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), Reno, NV, USA, 22–25 January 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, G.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y. A method for EWIS connector image identification in AR-based aircraft assembly process. Equip. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 49, 57–60,71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Research and application of China southern airlines new maintenance mode based on AR technology. Aviat. Maint. Eng. 2022, 11, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzis, D.; Siatras, V.; Angelopoulos, J. Real-Time Remote Maintenance Support Based on Augmented Reality (AR). Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utzig, S.; Kaps, R.; Azeem, S.M.; Gerndt, A. Augmented reality for remote collaboration in aircraft maintenance tasks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2–9 March 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.W.; Yan, H.; Lu, C.; Xiaofeng, X.; Zhibin, X. Design and implementation of civil aircraft structure maintenance platform based on B/S. Prog. Aeronaut. Eng. 2021, 12, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G. China Telecom’s 5G Customized Network Project Has Surpassed 2500 Cloud-Network Integration Practices and Continues to Progress. Available online: https://www.c114.com.cn/news/117/a1199116.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Qian, Y.X.; Tong, B.W.; Ding, H.Y. Aircraft maintenance of China Southern Airlines enters the Smart Maintenance Era. Air Transp. Bus. 2020, 20, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Gogolák, L.; Sárosi, J.; Fürstner, I. Augmented Reality Based Distant Maintenance Approach. Actuators 2023, 12, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Méndez, G.; del Cerro Velázquez, F. Augmented Reality in Industry 4.0 Assistance and Training Areas: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Electronics 2024, 13, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J. Artificial intelligence may change the MRO industry. Jetliner 2024, 13, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.F., Jr.; Hoskere, V.; Narazaki, Y. Advances in computer vision-based civil infrastructure inspection and monitoring. Engineering 2019, 5, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, T.; Abdollahzadeh, M.; Nejati, H.; Cheung, N.-M. Aircraft fuselage defect detection using deep neural networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.09213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.; Larnier, S.; Herbulot, A.; Devy, M. UAV-based inspection of airplane exterior screws with computer vision. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2019), Prague, Czech Republic, 25–27 February 2019; pp. 421–427. [Google Scholar]

- Avdelidis, N.P.; Tsourdos, A.; Lafiosca, P.; Plaster, R.; Plaster, A.; Droznika, M. Defects Recognition Algorithm Development from Visual UAV Inspections. Sensors 2022, 22, 4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouarfa, S.; Doğru, A.; Arizar, R.; Aydoğan, R.; Serafico, J. Towards Automated Aircraft Maintenance Inspection. A use case of detecting aircraft dents using Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2020 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–10 January 2020; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; p. 398. [Google Scholar]

- Brandoli, B.; de Geus, A.R.; Souza, J.R.; Spadon, G.; Soares, A.; Rodrigues, J.F., Jr.; Komorowski, J.; Matwin, S. Aircraft Fuselage Corrosion Detection Using Artificial Intelligence. Sensors 2021, 21, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Sun, C.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Yan, R. Deep learning-based borescope image processing for aero-engine blade in-situ damage detection. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 107473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Li, J.; King, S.; Addepalli, S. A Deep-Learning-Based Approach for Aircraft Engine Defect Detection. Machines 2023, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maggio, L.G. Toward Autonomous LLM-Based AI Agents for Predictive Maintenance: State of the Art, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Karigiannis, J.; Gao, R.X. Ontology-integrated tuning of large language model for intelligent maintenance. CIRP Ann. 2024, 73, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Ye, J.Y.; Cui, X.L.; Pang, W.; Li, Y.S.; Ni, P.C.; Feng, J.K. The challenges and exploration in the application of generative LLM key technologies for the civil aviation maintenance. Aviat. Maint. Eng. 2024, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Chou, J.; Tien, A.; Zhou, X.; Baumgartner, D. AviationGPT: A large language model for the aviation domain. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation Forum and Ascend 2024, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 29 July–2 August 2024; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2024; p. 4250. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi Kumar, G.V.V.; Kiran, K.; Devaraja Holla, V.; Venugopal, R.; Senthil, S.M.; Krishnasagar, M.K. Transforming Aviation Maintenance with the Infosys Generative AI Solution Built on Amazon Bedrock. 2023. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/cn/blogs/apn/transforming-aviation-maintenance-with-the-infosys-generative-ai-solution-built-on-amazon-bedrock (accessed on 2 September 2025).

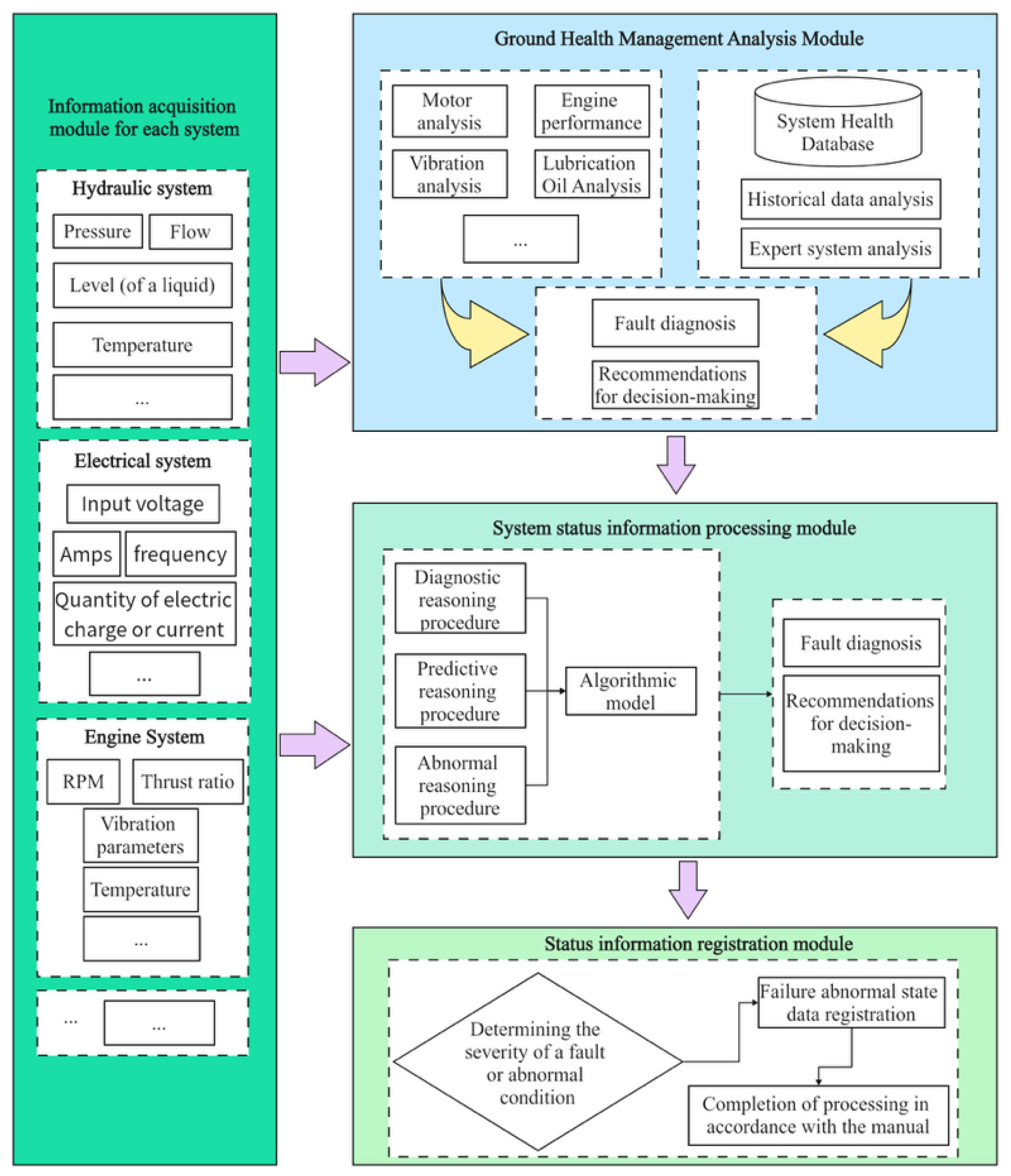

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cui, S. Application architecture and typical cases of big data technology in health management of civil aircraft system. Vib. Proced. 2019, 22, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J. Civil aircraft health management research based on big data and deep learning technologies. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management (ICPHM), Dallas, TX, USA, 19–21 June 2017; pp. 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani, M.; Yazdanparast, Z. From distributed machine to distributed deep learning: A comprehensive survey. J. Big Data 2023, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Y. An overview of Hadoop applications in transportation big data. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 10, 900–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Huang, S.; Su, C. Elevating Smart Manufacturing with a Unified Predictive Maintenance Platform: The Synergy between Data Warehousing, Apache Spark, and Machine Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattach, O.; Moussaoui, O.; Hassine, M. End-to-End Architecture for Real-Time IoT Analytics and Predictive Maintenance Using Stream Processing and ML Pipelines. Sensors 2025, 25, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Rouf, R.; Mazur, K.; Kontsos, A. The Industry Internet of Things (IIoT) as a Methodology for Autonomous Diagnostics in Aerospace Structural Health Monitoring. Aerospace 2020, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HACARUS Inc. Sparse Modeling Delivers Fast, Energy Efficient and Explainable AI Solutions for Cutting-Edge Medical Applications. 2021. Available online: https://media.nature.com/original/magazine-assets/d43747-021-00040-y/d43747-021-00040-y.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Lei, P.; Wang, X.; Jiang, L.; Xuan, L.; Cheng, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Leveraging large self-supervised time-series models for transferable diagnosis in cross-aircraft type Bleed Air System. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Ge, Y.J.; Liu, P.F. Aircraft predictive maintenance: A combination of data exploration and explainable data models. Stat. Appl. 2023, 12, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Ven, G.M.; Soures, N.; Kudithipudi, D. Continual learning and catastrophic forgetting. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.05175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Air Transport Association. Aircraft Operational Data. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/programs/ops-infra/techops/aircraft-operational-data (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Aerospace Industries Association. Considering Security of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Essential in Aviation. Available online: https://www.aia-aerospace.org/wp-content/uploads/Securing-Artificial-Intelligence-Machine-Learning-Aviation.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Jung, J.S.; Son, C.; Rimell, A.; Clarkson, R.J.; Karl, A.H. Impact of data quality on predictive engine health model using machine learning. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2024 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–12 January 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Si, X. A review on physics-informed data-driven remaining useful life prediction: Challenges and opportunities. Mech. Syst. Sig. Process. 2024, 209, 111120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. EASA Artificial Intelligence (AI) Concept Paper Issue 2: Guidance for Level 1&2 Machine Learning Application. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/document-library/general-publications/easa-artificial-intelligence-concept-paper-issue-2 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

| Comparison Items | Data-Driven Real-Time Fault Diagnosis and Maintenance | Data-Driven Predictive Maintenance |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Analyzing current status using real-time data and machine learning models to trigger maintenance [50] | Using historical and real-time data to predict future conditions and plan long-term maintenance [50] |

| Objective | Real-time anomaly detection and immediate maintenance decisions | Early warning of potential issues to optimize resource and time allocation |

| Time Dimension | Current state analysis | Future state prediction |

| Method | Classification or anomaly detection models for real-time data analysis | Regression models and time series analysis for forecasting future states [56] |

| Data Requirement | Driven by real-time data | Driven by both historical and real-time data |

| Decision Mode | Reactive decision-making: triggered by condition monitoring models | Planned decision-making: based on trend prediction models |

| Typical Application | Real-time analysis of engine vibration signals to detect anomalies and trigger maintenance [56] | Training regression models with historical data to predict the remaining useful life of components and systems [50] |

| Advantages | Strong real-time capability; ideal for systems with rich monitoring data | Excellent performance for complex systems; suitable for data-rich forecasting scenarios |

| Limitations | Requires large volumes of real-time data; may lack interpretability regarding physical mechanisms | High requirements for historical data quality and quantity |

| Classification of Methods | Author (Source of Literature) | Object of Study | The Specific Application of Fault Diagnosis or Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curve-fitting | Xu et al. [92] | Prediction of aircraft Engine vibration faults | The vibration and rotational speed parameter curves in QAR data are used for fitting to predict the vibration fault trend of the engine |

| Grey system theory | Yang [93] | Fault diagnosis of aero engines | The grey system theory combined with QAR data analysis improves the effect of engine fault diagnosis |

| Regression analysis | Wang et al. [94] | Diagnosis of engine fuel consumption and oil leakage faults | The multiple linear regression model using QAR data is used to monitor engine oil leakage faults in real-time |

| Cao et al. [95] | Abnormal fault diagnosis of aircraft engines | A healthy gas path regression model is established based on QAR data to achieve real-time diagnosis of abnormal engine conditions | |

| Wang [96] | Real-time fault diagnosis of engine status | A support vector regression model is established based on QAR data to diagnose the engine failure status in real-time | |

| Control Chart Analysis | Liang et al. [97] | Fault diagnosis of the air intake system | The QAR data are processed by using the exponentially weighted moving average control chart to improve the accuracy of fault diagnosis and early warning ability of the gas intake system |

| Machine learning method | Jiang [98] | Health assessment and fault diagnosis of posterior edge flaps | Principal component analysis and GRU neural network model were conducted using QAR data to diagnose flap performance faults |

| Zhang et al. [89] | QAR data fault diagnosis | The CNN-LSTM dual-channel model extracts the features of QAR data and is used for fault diagnosis of aircraft systems | |

| Memarzadeh et al. [99] | Fault diagnosis during the take-off stage of commercial flights | The CVAE deep generative model processes QAR data and identifies abnormal states during the takeoff phase for fault diagnosis | |

| Wang [100] | Fault diagnosis of flight cycle decay state | After the QAR data are visualized, different flight decay states are diagnosed by CNN | |

| Huo [101] | Fault diagnosis of abnormal parameters in QAR data | The sliding window combined with HMM is used to analyze QAR data, discover abnormal parameters, and assist in the analysis of fault causes | |

| Duan [102] | Flight data fault diagnosis and prediction | The Transformer network processes QAR data and extracts features to achieve fault prediction | |

| Huang [103] | QAR data fault diagnosis | Damage state evaluation method of service turbine blades based on MAML-LSTM |

| Method | Main Principle | Typical Algorithms | Advantages | Limitations | Related Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical | Assumes that data follows a certain distribution (e.g., normal distribution); identifies outliers based on statistical features such as mean, variance, and skewness | 3σ Rule | Simple to compute, highly interpretable, suitable for data with known or approximately standard distribution | Limited performance on high-dimensional or non-linear data | Traditional methods |

| Classification | Treated as a supervised learning task; trains a classification model on labeled normal/anomalous s data and classifies new data | SVM, Decision Tree, Neural Network | High accuracy, suitable when anomalous samples are abundant | Requires a large amount of labeled data; anomalies are often rare and hard to label in practice | Sun et al. [116] proposed an improved SVDD method for detecting anomalies in flight data |

| Clustering | Uses unsupervised learning to divide data into clusters and identifies data points far from cluster centers as anomalies | K-Means, Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN) | No need for labelled data, suitable for detecting unknown patterns | Heavily influenced by clustering parameters and data dimensions | Fei et al. [117] proposed a clustering-based anomaly detection method to improve anomaly detection efficiency in flight data |

| Regression | Builds mapping relationships among normal data to predict variable values; detects anomalies based on deviations | Linear Regression, Polynomial Regression, ARIMA, LSTM | Suitable for data with clear correlations | Sensitive to noise and difficult to handle complex non-linear data | Shi et al. [118] studied regression analysis of spacecraft telemetry parameters for anomaly detection |

| Proximity-based | Detects anomalies based on density distribution of data points in feature space | K-Nearest Neighbors, Local Outlier Factor | No distribution assumptions needed; works well with high-dimensional data | High computational complexity; inefficient for large datasets | Kumar et al. [119] proposed an unsupervised hybrid statistical–local outlier factor algorithm to detect anomalies in time-series flight data |

| Fault Description | On 4 July 2020, while the JZ-9 aircraft was flying over Shanghai, a burn occurred at the 12 o’clock direction of the engine nozzle insulation screen. Inspection revealed circumferential cracks on the outer ring of the booster oil ring. The engine was manufactured by Factory 0123. | ||||

| Extracted Information | Aircraft Model | Location | Date of Occurrence | Fault Part Name | Manufacturer of Fault Part |

| JZ-9 | Shanghai | 2020-07-04 | Engine Nozzle Insulation Screen and Booster Oil Ring | Factory 0123 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, C.; Gu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ba, X.; Sun, D.; Xu, J. Big Data Empowering Civil Aircraft Health Management: A Full-Cycle Perspective. Aerospace 2026, 13, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010024

Ma C, Gu Z, Wu Y, Ba X, Sun D, Xu J. Big Data Empowering Civil Aircraft Health Management: A Full-Cycle Perspective. Aerospace. 2026; 13(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Chao, Zhengbo Gu, Yaogang Wu, Xiang Ba, Donglei Sun, and Jianxin Xu. 2026. "Big Data Empowering Civil Aircraft Health Management: A Full-Cycle Perspective" Aerospace 13, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010024

APA StyleMa, C., Gu, Z., Wu, Y., Ba, X., Sun, D., & Xu, J. (2026). Big Data Empowering Civil Aircraft Health Management: A Full-Cycle Perspective. Aerospace, 13(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010024