Aerospike Aerodynamic Characterization at Varying Ambient Pressures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Approach

3. Geometry

4. Simulation Settings

4.1. Domain Size

4.2. Mesh

4.3. Boundary and Initial Conditions

- Inlet: The total pressure at the inlet linearly increases from the ambient pressure to the working conditions ( ) in the first 33 . The temperature rises smoothly, reaching the combustion chamber value of 3340 . If the flow moves into the domain, the velocity adapts according to the pressure difference between the inlet and the cell centre that has a face belonging to this boundary, while, otherwise, a zero gradient condition is imposed. and k have been obtained using Equations (5)–(9).Equation (6) was introduced by Menter in [35]. Equation (7) is explained in Appendix B.2. The turbulence intensity has been estimated using the empirical law shown in [48] (its derivation is explained in Appendix B.1), according to [35,36,49], , and the characteristic length has been chosen as the hydraulic diameter of the inlet :and are, respectively, the internal and the external inlet radii, while is the inlet perimeter. can be estimated by solving the following equation for the inlet Mach number .where is the inlet section area, is the throat section area, and is the heat capacity ratio at the throat section.is the speed of sound in the combustion chamber, and it is one of the CEA outputs.

- Walls: The normal pressure gradient on the wall has been set to zero. Then, a no slip condition has been applied to the velocity and the adiabatic wall condition has been set for the temperature. Turbulence specific dissipation and turbulent kinetic energy k have been modelled using wall functions [50]. They allow us to describe the behaviour of these two variables and to have a coarser grid resolution close to the wall as long as the first cell centre starting from it falls in the log-layer region. Otherwise, the height of these cells should be smaller than the viscous sublayer thickness, which is very small. The wall functions employed herein are reported in the OpenFOAM Guide [50]. A stepwise switch has been adopted between the inertial sublayer and the viscous one.

- Outlet: The flow velocity adapts accordingly to the pressure difference between the last cell centre close to the outlet and the pressure imposed at the outlet itself. Regarding pressure, a boundary condition that damps the wave reflection, imposing an advection velocity, has been used,where is the advection speed, is the flow velocity in the direction normal to the boundary, is the distance normal to the boundary at which the pressure should reach , and is the partial derivative along a direction normal to the boundary. This boundary condition was introduced by Poinsot and Lele [51], and it has been used in other scientific works [45,52,53]. has been imposed: this value is a compromise between wave reflection and the need to have the desired ambient pressure at the outlet. has been set equal to . Regarding T, , and k, a zero flux has been imposed when the flow exits the domain, while they have been set to given values, respectively, , , and , when the flow enters the domain. and have been evaluated using the following formula, where the characteristic length employed to estimate the turbulence length scale is the engine external diameter: [54] (ch. 3.7.1). Therefore,where is the external flow speed.

- Farfields: A null flux is imposed when the flow exits the domain, while, in the opposite case, a fixed velocity is set parallel to the engine axis:In static simulations, should be equal to zero, but to avoid the presence of a totally quiescent flow and the consequent numerical issue, a small velocity is applied to have an equivalent Mach number of . For an inflow, the pressure flux is set to zero, while for an outflow the pressure is set to . Regarding the temperature, it is the opposite: the ambient temperature is imposed when the flow enters the domain and a temperature flux equal to zero is imposed when the flow exits it. The same boundary conditions set at the outlet are used for k and ,with .

- lateral surface: OpenFOAM also requires a boundary condition, called wedge, for the lateral surfaces in order to set a 2D axisymmetric simulation.

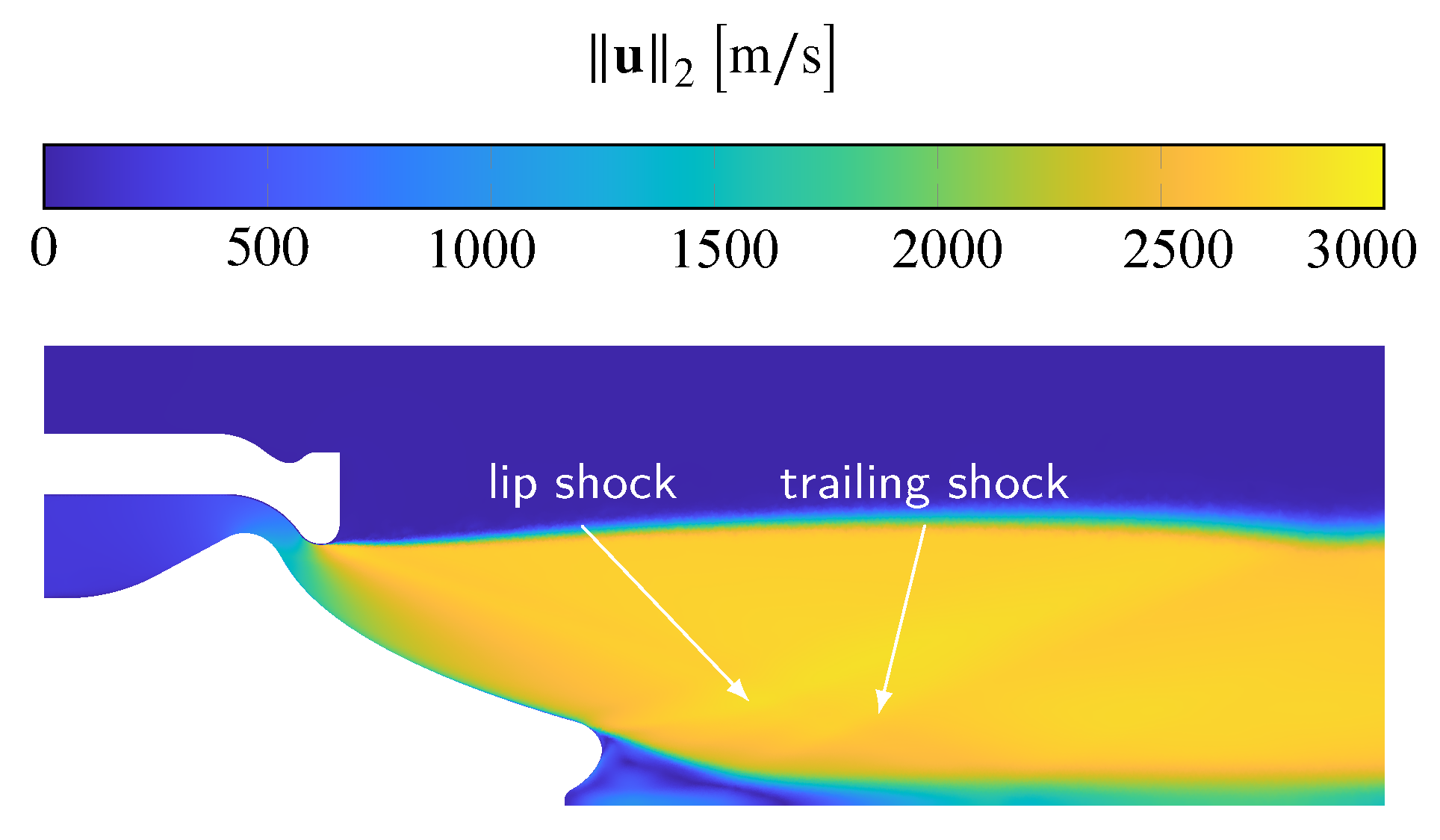

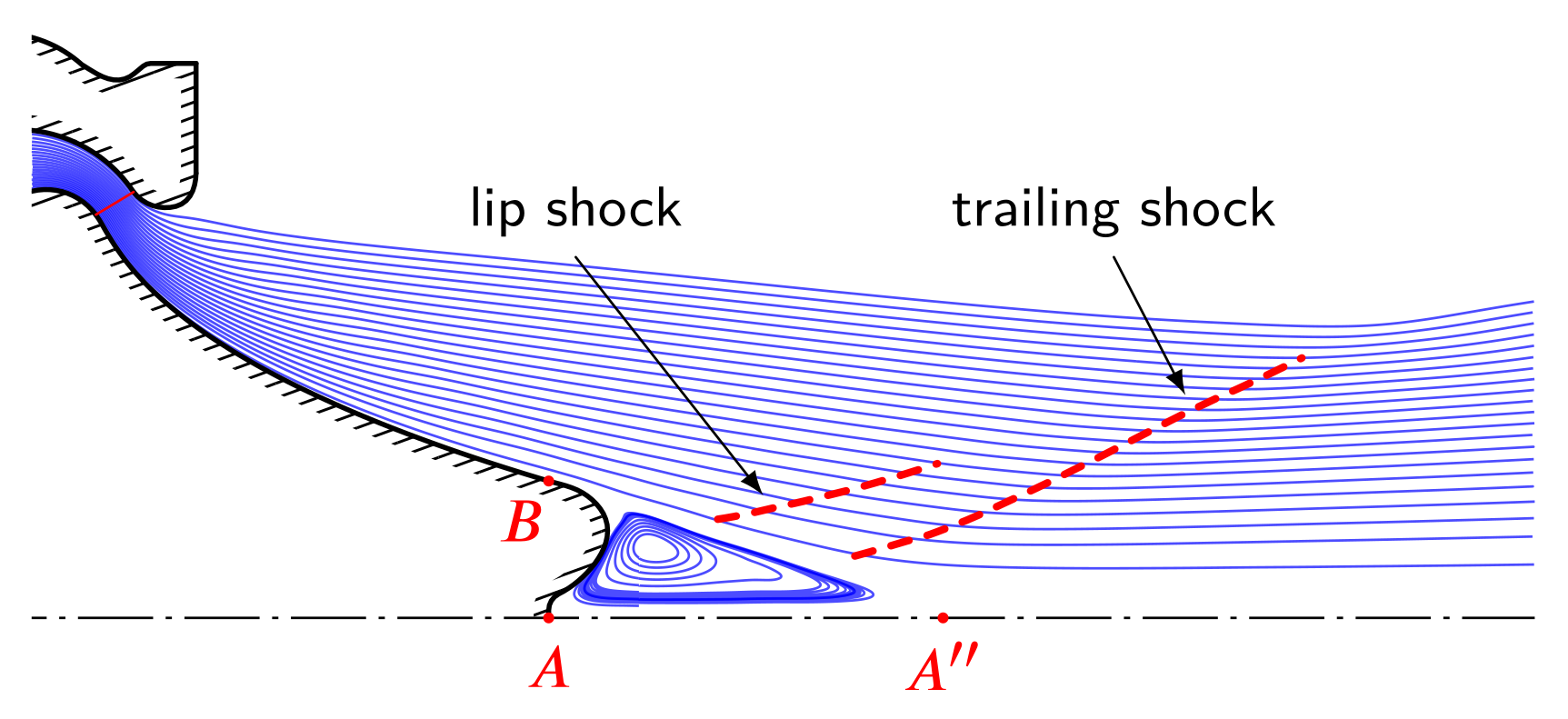

5. Static Simulation Results at Different Ambient Pressures

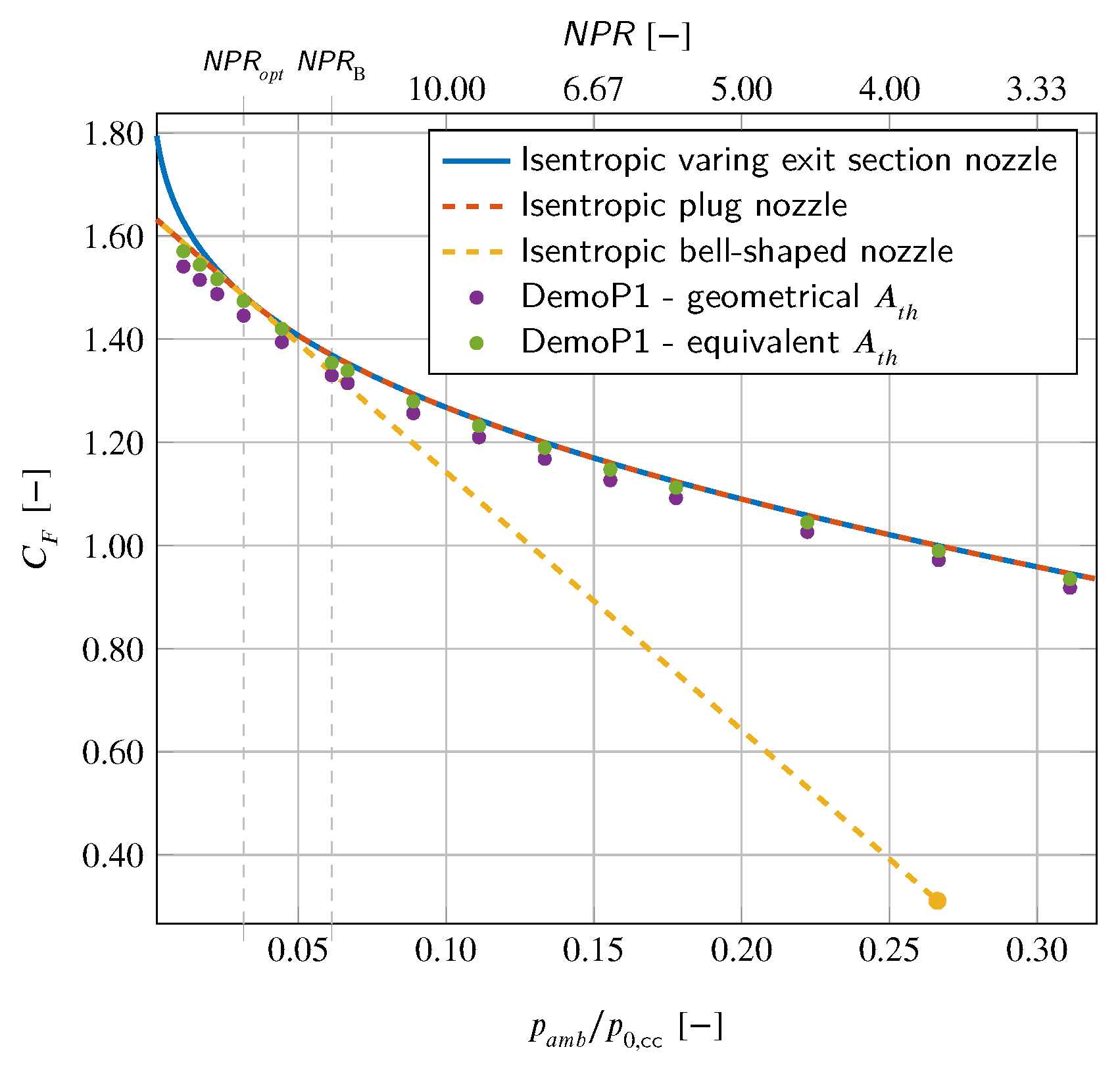

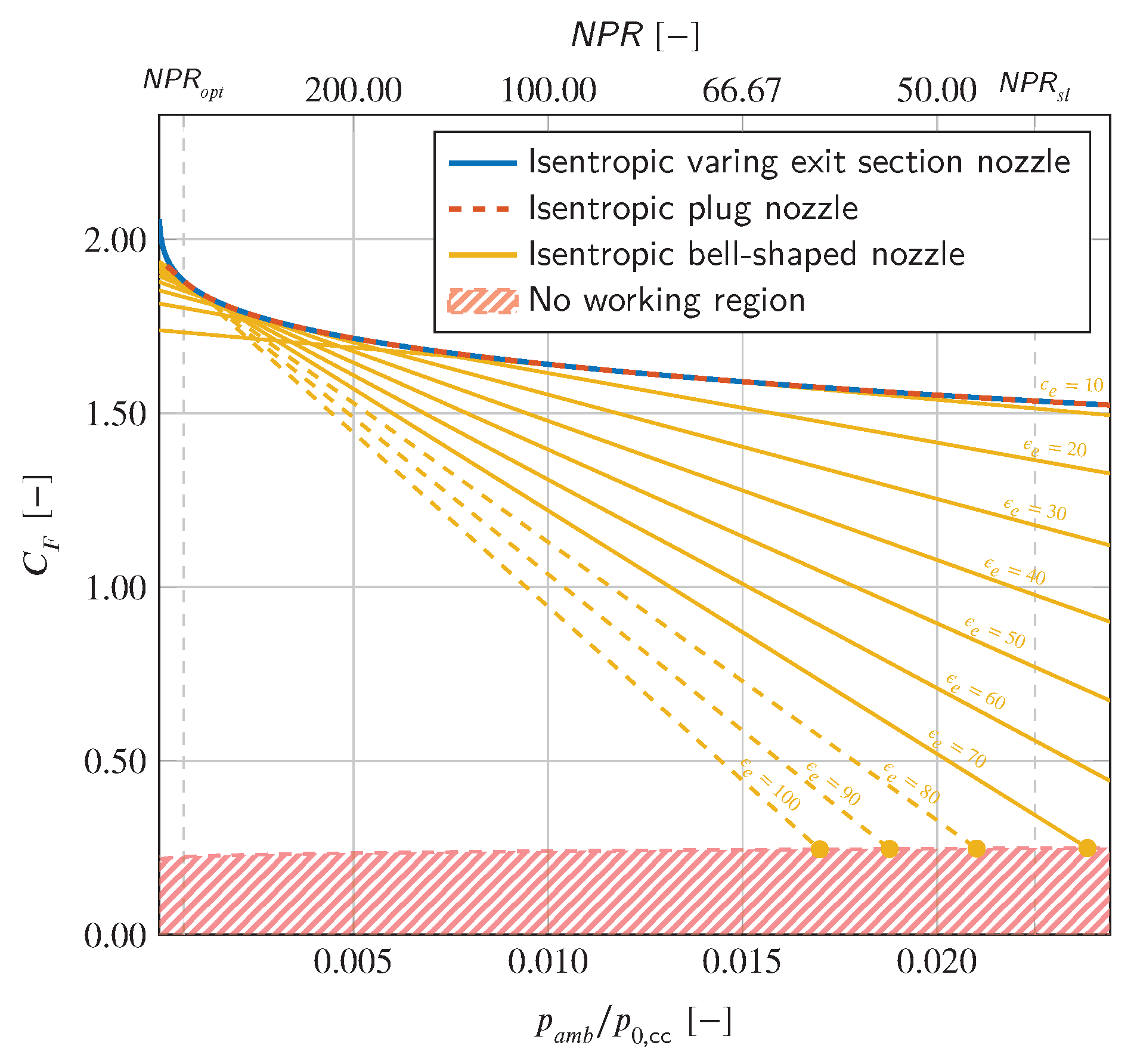

5.1. Aerospike Performance

5.2. Single Stage to Orbit Design

5.3. Thrust Delivered by Individual Engine Surface

5.3.1. Theoretical Thrust Delivered by Each Surface

- : The Prandtl–Meyer expansion ends over the spike;

- : The Prandtl–Meyer expansion ends at the end of the spike or beyond it.

5.3.2. Comparison of the Thrust Coefficients Generated by Each Surface

5.3.3. Theoretical Thrust Coefficient Delivered by the Base

5.4. Spike

Pressure Distribution

5.5. Base

5.5.1. Pressure Distribution

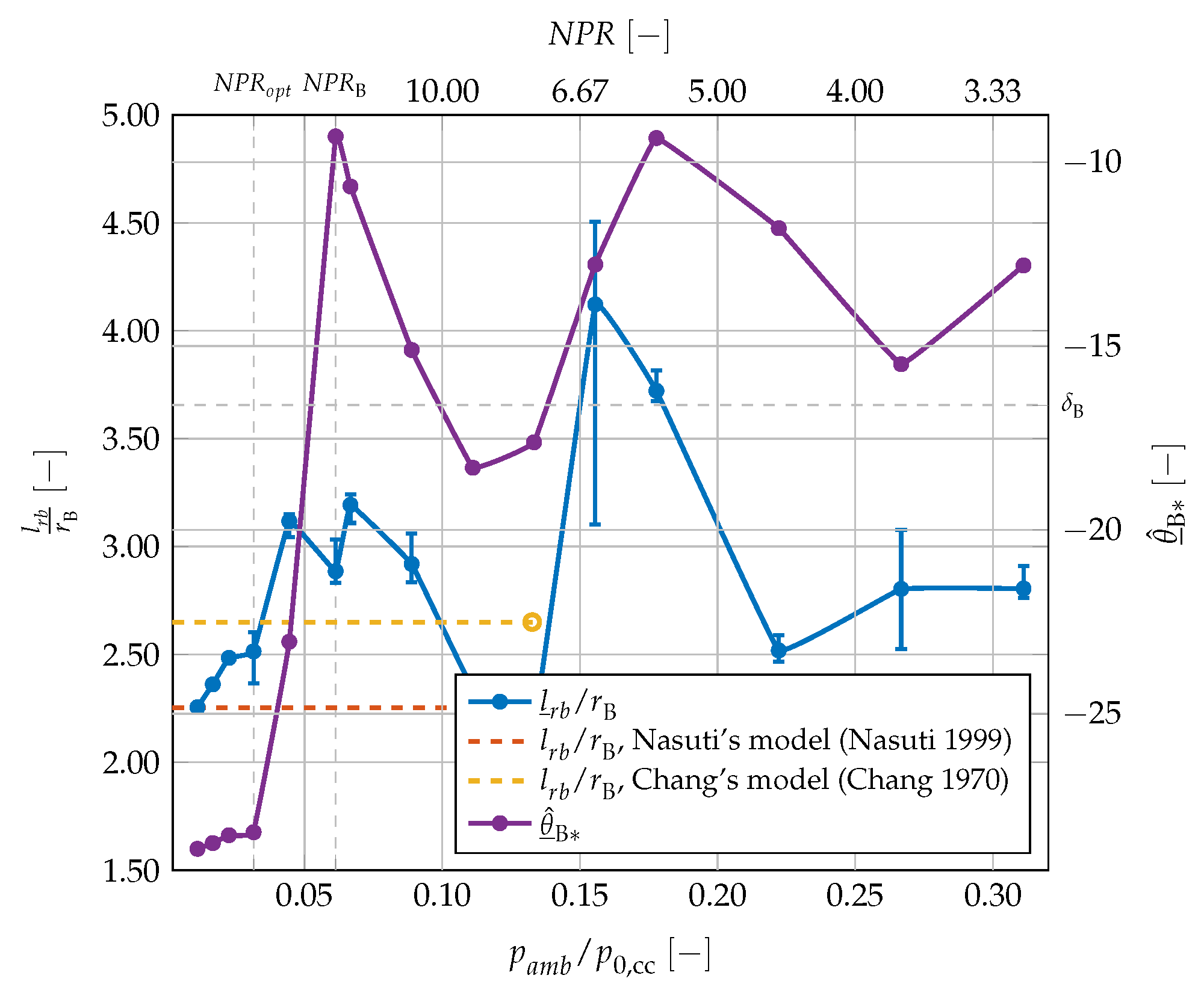

5.5.2. Recirculating Bubble

- : the flow is confined close to the spike wall. Hence, an average pressure value along the segment could be evaluated aswhere is the instantaneous mass flow rate. Point always lies above the shear layer. is used to evaluate an average Mach numberThe new average flow direction could be evaluated by applying the Prandlt–Meyer expansion theory and then averaging over the time,where is the flow direction after the expansion while is calculated using Equations (51) and (52).

- : only the flow close to the aerospike has an influence on the bubble length. Therefore, the procedure is similar to the one presented before, but and are substituted with the pressure at point and , where the latter is the slope of the spike at point itself.

5.5.3. Open- and Closed-Wake Conditions

6. Flow Separation at the Fillet

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| CEA | Chemical Equilibrium with Applications |

| SST | Shear Stress Transport |

| HLLC | Harten, Lax, van Leer, Contact |

| OpenFOAM | Open Field Operation And Manipulation |

| SSTO | Single Stage To Orbit |

| SWBLI | Shock Wave–Boundary Layer Interaction |

| DLR | Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt |

| Nozzle pressure ratio, - | |

| k | Turbulent kinetic energy, |

| Specific dissipation rate, | |

| p | Static pressure, |

| Total pressure, | |

| T | Static temperature, |

| Total temperature, | |

| Specific heat capacity at constant pressure, | |

| Heat capacity ratio, - | |

| Molar mass, | |

| Flow density, | |

| Speed of sound, | |

| Dynamic viscosity, | |

| Prandtl number, - | |

| Simulation time step, | |

| Post-processing time interval, | |

| , | Post-processing time interval extreme value, |

| r | Radial coordinate, |

| Position vector, | |

| t | Time, |

| Aerospike exit section diameter, | |

| Distance of the vertical farfield from the throat section, | |

| Distance between the outlet and the throat section, | |

| Distance of the horizontal farfield from the engine axis, | |

| Aerospike external wall radius, | |

| Aerospike exit section radius, | |

| M | Mach number, - |

| Mach angle, | |

| Effective area, | |

| A | Geometrical area, |

| Safety factor for area estimation, - | |

| Velocity vector, | |

| U | Velocity module, |

| I | Turbulence intensity, - |

| l | Turbulence length scale, |

| L | Engine length scale, |

| k- SST parameter, - | |

| Hydraulic diameter | |

| Reynolds number, - | |

| Perimeter, | |

| Distance from the boundary to the actual farfield region at which the | |

| pressure should be , | |

| Pressure at distance from the boundary, | |

| Advection speed, | |

| External flow speed, | |

| Number of cells in the mesh, - | |

| Execution time, | |

| Execution time in percentage with respect the one required by the finest mesh, - | |

| Thrust calculated from the j-th mesh, | |

| Percentage variation in thrust compared to that calculated from the finest mesh, - | |

| Percentage variation in pressure distribution compared to that calculated from | |

| the finest mesh, - | |

| Mass flow rate difference with respect to the theoretical case, | |

| Standard deviation of the mass flow rate, | |

| Discharge coefficient, - | |

| Aspect ratio, - | |

| Mass flow rate, | |

| Specific gas constant, | |

| Thrust coefficient, - | |

| F | Thrust, |

| Unit normal vector, - | |

| Thrust delivered by the surface j, | |

| j-th surface | |

| I | Identity matrix, - |

| Shear stress tensor, | |

| Angle between flow velocity and engine axis, | |

| Estimated flow angle after the spike end, | |

| Flow direction change, | |

| Averaged momentum variation through the line , | |

| Wall slope, | |

| Thrust coefficient delivered by the surface j, - | |

| Ratio between the aerospike base radius and the exit section radius, - | |

| Unit vector parallel to the engine axis, - | |

| Unit vector parallel to the radial direction, - | |

| Unit vector tangent to the wall, - | |

| Wall shear stress projected along the wall, | |

| Angle through which a flow turns due to Prandtl–Meyer expansion, | |

| cc | Combustion chamber |

| wss | Wall shear stress |

| inlet | Inlet |

| base | Base |

| Throat section | |

| w | Engine wall |

| f | Farfield |

| o | Outlet |

| e | Engine exit section |

| Engine axis | |

| Ambient condition | |

| Sea level | |

| Every underlined symbol refers to a simulation result | |

| Design condition | |

| Time average value of variable | |

| Spatial average value of variable |

Appendix A. Mesh Convergence Analysis

| Mesh | [−] | [h] | [%] | [kN] | [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 26,184 | 34.60 | 7.17 | 21.37 | 0.361 |

| B | 40,157 | 47.92 | 9.92 | 21.40 | 0.202 |

| C | 70,597 | 116.97 | 24.22 | 21.42 | 0.105 |

| D | 93,651 | 227.49 | 47.11 | 21.44 | 0.027 |

| E | 124,670 | 482.92 | 100.00 | 21.45 | 0.000 |

| Surface Name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Combustion chamber | 1.67 × 10−4 | 0.857 | 0.128 |

| Converging nozzle | 1.44× 10−4 | 3.66 | 3.06 |

| Diverging nozzle | 5.00× 10−6 | 1.79 | 0.398 |

| Spike | 1.31 × 10−3 | 3.38 | 1.35 |

| Base | 4.00 × 10−6 | 1.17 × 10−3 | 2.93 × 10−4 |

| Vertical external wall | 2.30 × 10−5 | 2.37 × 10−4 | 1.05 × 10−4 |

| Horizontal external wall | 1.75 × 10−4 | 2.41 × 10−4 | 1.86 × 10−4 |

| External wall extension | 1.79 × 10−4 | 1.83 × 10−4 | 1.81 × 10−4 |

Appendix B. Turbulent Intensity and Length Scale

Appendix B.1. Empirical Turbulence Intensity Law

Appendix B.2. Turbulence Length Scale in Pipes

Appendix B.3. Turbulence Length Scale for Wake Flow

Appendix C. Ideal Plug Nozzle

Appendix D. Flow Inclination at the End of Prandlt–Meyer Expansion

References

- Hagemann, G.; Immich, H.; Van Nguyen, T.; Dumnov, G.E. Advanced Rocket Nozzles. J. Propuls. Power 1998, 14, 620–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, G.P.; Biblarz, O. Rocket Propulsion Elements, 9th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, P.G.; Peterson, C.R. Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Propulsion, 2nd ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Huzel, D.K.; Huano, D.H. Design of Liquid Propellant Rocket Engines, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, G.P.; Biblarz, O. Rocket Propulsion Elements, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S. Performance Characteristics of an Annular Conical Aerospike Nozzle with Freestream Effect. J. Propuls. Power 2009, 25, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, N.; Senthilkumar, P.; Dineshkumar, K.; Purusothaman, M.; Sriharan, B. CFD analysis on flow through nozzle of conical type and truncated conical plug type. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 72, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.P.; Suryan, A.; Kim, H.D. Computational study on flow through truncated conical plug nozzle with base bleed. Propuls. Power Res. 2019, 8, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Wang, J.P. Design and optimization of aerospike nozzle for rotating detonation engine. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 120, 107300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Liu, Y.; Qin, L.Z. Aerospike nozzle contour design and its performance validation. Acta Astronaut. 2009, 64, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Eri, Q.; Kong, B. Flow and thrust characteristics of an expansion–deflection dual-bell nozzle. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 107464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Eri, Q.; Huang, J.; Kong, B. Multi-objective aerodynamic optimization of expansion–deflection nozzle based on B-spline curves. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 147, 109016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xu, J.; Lv, H.; Lv, D.; Song, J. Numerical investigations of the nozzle performance for a rocket-based rotating detonation engine with film cooling. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 136, 108221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xia, H.; Chen, X.; Luan, Z.; You, Y. Shock dynamics and expansion characteristics of an aerospike nozzle and its interaction with the rotating detonation combustor. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 106969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Xu, J.; Li, R.; Zhou, J.; Yu, K. Numerical investigations of different liner lengths of axial film cooling for a rotating detonation engine. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 149, 109172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xu, J.; Lv, H.; Yu, K.; Zhou, J. Numerical investigations of the nozzle performance of a rotating detonation engine with axially adjustable cowl and spike. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 158, 109878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Jiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fan, W. Study on the performance of a rotating detonation chamber with different aerospike nozzles. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 107, 106338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.Z.; Bao, W.; Wang, J.P. Experimental research of the performance and pressure gain in continuous detonation engines with aerospike nozzles. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 140, 108464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Ma, J.Z.; Sheng, Z.; Rong, G.; Wu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Spinning pulsed detonation in rotating detonation engine. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 126, 107661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.; Schwer, D.; Agrawal, A.K. Profiling cross-sectional area of a radial rotating detonation combustor to increase pressure gain. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 133, 108096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Guo, Z.; Hao, Z.; Hedong, L.; Li, C. Numerical and experimental investigation of throttleable hybrid rocket motor with aerospike nozzle. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 105983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geron, M.; Paciorri, R.; Nasuti, F.; Sabetta, F. Flowfield analysis of a linear clustered plug nozzle with round-to-square modules. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2007, 11, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Yang, W.; Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Xv, C. Numerical investigation of thrust vector performance and flow separation in clustered annular aerospike nozzles with differential throttling. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2026, 168, 110919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer-Fischer, E.; Abel, J.; Sieder-Katzmann, J.; Propst, M.; Bach, C.; Scheithauer, U.; Michaelis, A. Study on CerAMfacturing of Novel Alumina Aerospike Nozzles by Lithography-Based Ceramic Vat Photopolymerization (CerAM VPP). Materials 2022, 15, 3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangea Aerospace, 2023. Available online: https://www.pangeapropulsion.com/en/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Rossi, F.; Esnault, G.; Sápi, Z.; Palumbo, N.; Argemi, A.; Bergström, R. Research Activities in the Development of DemoP1: A LOX/LNG Aerospike Engine Demonstrator. In Proceedings of the 7th Edition of the Space Propulsion Conference, Virtual, 17–19 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, F.; Sápi, Z.; Palumbo, N.; Demediuk, A.; Ampudia, M. Manufacturing and Hot-Fire Test Campaign of the DemoP1 Aerospike Engine Demonstrator. In Proceedings of the 8th Edition of the Space Propulsion Conference, Estroil, Portugal, 9–13 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aenium Engineering—High Performance Additive Manufacturing. 2023. Available online: https://aenium.es/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Argemí, A. Flight of the aerospike. Met. Powder Rep. 2021, 76, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadigati, L.; Rossi, F.; Souhair, N.; Ravaglioli, V.; Ponti, F. Development and simulation of a 3D printed liquid oxygen/liquid natural gas aerospike. Acta Astronaut. 2024, 216, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadigati, L. Numerical Simulation of the Flow and Performance Evaluation of an Aerospike Engine. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi, M.D.; Fadigati, L.; Souhair, N.; Ponti, F. Validation of a numerical strategy to simulate the expansion around a plug nozzle. In Materials Research Proceedings; MRF: Padova, Italy, 2023; Volume 37, pp. 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadigati, L.; Sozio, E.; Rossi, F.; Souhair, N.; Ponti, F. Advanced aerodynamic analysis of the supersonic flow field of an aerospike engine. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 158, 109908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, E.F. The HLLC Riemann solver. Shock Waves 2019, 29, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.R.; Kuntz, M.; Langtry, R. Ten Years of Industrial Experience with the SST Turbulence Model. In Proceedings of the Turbulence, Heat, and Mass Transfer, Antalya, Turkey, 12–17 October 2003; pp. 625–632. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, S.; McBride, B.J. Computer Program for Calculation of Complex Chemical Equilibrium Compositions and Applications I. Analysis; NASA Reference Publication; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, B.J.; Gordon, S. Computer Program for Calculation of Complex Chemical Equilibrium Compositions and Applications II. Users Manual and Program Description; NASA Reference Publication; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie, J.M.; Gordon, S. Lewis Research Center Cleveland, Ohio; NASA Reference Publication; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Angelino, G. Approximate method for plug nozzle design. AIAA J. 1964, 2, 1834–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EOS M 290-Mid-Size 3D Printing. 2023. Available online: https://www.eos.info/it?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=brand_emea&utm_term=eos%203d&utm_campaign=%5Bwyn%5D+Brand+%5BIT%5D+%5BS%5D&utm_source=adwords&utm_medium=ppc&hsa_acc=3851378066&hsa_cam=22294787911&hsa_grp=172971710822&hsa_ad=735217097744&hsa_src=g&hsa_tgt=kwd-390601728&hsa_kw=eos%203d&hsa_mt=p&hsa_net=adwords&hsa_ver=3&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22294787911&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIxYSy4PjGkQMVb62DBx0L9iZhEAAYASAAEgI6XPD_BwE (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cooper, K.G.; Lydon, J.L.; LeCorre, M.D.; Jones, Z.C.; Scannapieco, D.S.; Ellis, D.L.; Lerch, B.A. Three-Dimensional Printing GRCop-42; Technical Report; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gradl, P.R.; Greene, S.E.; Protz, C.; Bullard, B.; Buzzell, J.; Garcia, C.; Wood, J.; Osborne, R.; Hulka, J.; Cooper, K.G. Additive Manufacturing of Liquid Rocket Engine Combustion Devices: A Summary of Process Developments and Hot-Fire Testing Results. In Proceedings of the 2018 Joint Propulsion Conference, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 9–11 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soman, S.; Suryan, A.; Nair, P.P.; Dong Kim, H. Numerical Analysis of Flowfield in Linear Plug Nozzle with Base Bleed. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2021, 58, 1786–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, B.; Vevek, U.S.; Tze How, D.N. OpenFOAM based numerical simulation study of an underexpanded supersonic jet. In Proceedings of the 55th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Grapevine, TX, USA, 9–13 January 2017; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jency, A.; Bajpai, A.; Appar, A.; Kumar, R. Comparative analysis of flow field and thrust behaviour of plug nozzles in continuum vs. rarefied conditions. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 157, 109821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, D. Turbulence Modeling for CFD, 3rd ed.; Hardcover; DCW Industries: La Canada, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson, M.A. ANSYS Fluent User’s Guide, 2022 R1. 2022. Available online: https://ansyshelp.ansys.com/public//Views/Secured/corp/v252/en/flu_ug/flu_ug.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Wilcox, D.C. Reassessment of the scale-determining equation for advanced turbulence models. AIAA J. 1988, 26, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenFOAM: User Guide: OmegaWallFunction. 2021. Available online: https://www.openfoam.com/documentation/guides/latest/doc/guide-bcs-wall-turbulence-omegaWallFunction.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Poinsot, T.J.; Lelef, S.K. Boundary conditions for direct simulations of compressible viscous flows. J. Comput. Phys. 1992, 101, 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurashev, D.; Campa, G.; Anisimov, V.V.; Cosatto, E. Two-step approach for pressure oscillations prediction in gas turbine combustion chambers. Int. J. Spray Combust. Dyn. 2017, 9, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchese, L. Implementation of non-reflecting boundary conditions in OpenFOAM. In CFD with OpenSource Software; Chalmers University: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg, H.K.; Malalasekera, W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method, 2nd ed.; Pearson/Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- George, E. Prandtl-Meyer Flow and Shock-Expansion Theory. In Gasdynamics—Theory and Applications; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Nasuti, F.; Onofri, M. Theoretical Analysis and Engineering Modeling of Flowfields in Clustered Module Plug Nozzles. J. Propuls. Power 1999, 15, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofri, M.; Calabro, M.; Hagemann, G.; Immich, H.; Sacher, P.; Nasuti, F.; Reijasse, P. Plug nozzles: Summary of flow features and engine performance-Overview of RTO/AVT WG 10 subgroup 1. In Proceedings of the 40th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting & Exhibit, Aerospace Sciences Meetings, Reno, NV, USA, 14–17 January 2002; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, I.R.; Laín, S.; Lopez, O.D. A Review of Aerospike Nozzles: Current Trends in Aerospace Applications. Aerospace 2025, 12, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutkey, K.; Vasudevan, B.; Balakrishnan, N. Analysis of Annular Plug Nozzle Flowfield. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2014, 51, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.K. Separation of Flow; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Herrin, J.L.; Dutton, J.C. Supersonic base flow experiments in the near wake of a cylindrical afterbody. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, M.; Schmucker, R.H. Performance aspects of plug cluster nozzles. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 1996, 33, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galileo100. 2023. Available online: https://www.hpc.cineca.it/systems/hardware/galileo100/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- De Lemos, M.J. Applications in Hybrid Media. In Turbulence in Porous Media; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 199–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennekes, H.; Lumley, J.L. A First Course in Turbulence; The Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Blasius, H. Das Aehnlichkeitsgesetz bei Reibungsvorgängen in Flüssigkeiten. In Mitteilungen über Forschungsarbeiten auf dem Gebiete des Ingenieurwesens; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1913; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikuradse, J. Laws of Flow in Rough Pipes; National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA): Washington, DC, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Antonialli, L.A.; Silveira-Neto, A. Theoretical Study of Fully Developed Turbulent Flow in a Channel, Using Prandtl’s Mixing Length Model. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 2018, 6, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Thermodynamic Properties | |

|---|---|

| 2.552 | |

| 3140 | |

| 2452 | |

| 1.206 | |

| 19.84 | |

| 3.1089 | |

| 1272 | |

| Transport Properties | |

|---|---|

| 1 × 10−4 | |

| 0.651 | |

| 1 × 10−4 | |

| Boundary Name | p | u | T | k | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inlet | timeVarying TotalPressure | pressureInlet OutletVelocity | timeVarying UniformFixedValue | fixedValue | fixedValue |

| outlet | waveTransmissive | pressureInlet OutletVelocity | inletOutlet | inletOutlet | inletOutlet |

| vertical farfield | waveTransmissive | pressureInlet OutletVelocity | inletOutlet | inletOutlet | inletOutlet |

| horizontal farfield | waveTransmissive | pressureInlet OutletVelocity | inletOutlet | inletOutlet | inletOutlet |

| walls | zeroGradient | fixedValue | zeroGradient | kqRWallFunction | compressible:: omegaWallFunction |

| lateral surface | wedge | wedge | wedge | wedge | wedge |

[kg/s] | [g/s] | [kg/s] | [kg/s] | [−] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.695 | 4.174 | 7.838 | −0.143 | 0.982 |

| Inlet | Combustion Chamber | Converging Nozzle | Fillet | Spike Prandtl–Meyer Expansion | Spike Last Part | Base | External Wall | Total | Theoretical | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under-exp. | 0.01 | 90.00 | −0.41 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 3.38 | −0.29 | −6.35 | −0.11 | 1.52 | −0.37 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.17 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.01 | −0.87 | −2.88 | 1.59 |

| 0.02 | 60.00 | −0.41 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 3.46 | −0.31 | −6.37 | −0.11 | 1.59 | −0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.13 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −1.82 | −1.00 | −2.83 | 1.56 | |

| 0.02 | 44.41 | −0.42 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 3.49 | −0.31 | −6.36 | −0.11 | 1.64 | −0.52 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.12 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −1.73 | −1.02 | −2.75 | 1.53 | |

| Optimal exp. | 0.03 | 31.76 | −0.43 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 3.68 | −0.36 | −6.36 | −0.11 | 1.66 | −0.52 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.12 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −1.55 | −1.09 | −2.64 | 1.48 |

| Over-expansion | 0.04 | 22.50 | −0.43 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 3.75 | −0.28 | −6.27 | −0.10 | 1.75 | −0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.50 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −1.69 | −0.65 | −2.33 | 1.43 |

| 0.06 | 16.32 | −0.45 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 3.94 | −0.30 | −6.13 | −0.10 | 1.82 | −0.21 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −1.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.22 | −0.66 | −2.88 | 1.37 | |

| 0.07 | 15.00 | −0.45 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 3.99 | −0.30 | −6.03 | −0.09 | 1.81 | −0.20 | 0.16 | 0.00 | −1.66 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.16 | −0.66 | −2.82 | 1.35 | |

| 0.09 | 11.25 | −0.46 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 4.21 | −0.31 | −5.71 | −0.09 | 1.56 | −0.19 | 0.33 | 0.00 | −2.17 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.23 | −0.66 | −2.88 | 1.29 | |

| 0.11 | 9.00 | −0.47 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 4.42 | −0.33 | −5.36 | −0.08 | 1.17 | −0.17 | −0.18 | −0.01 | −1.64 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −2.07 | −0.65 | −2.72 | 1.24 | |

| 0.13 | 7.50 | −0.48 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 4.62 | −0.34 | −4.91 | −0.08 | 0.66 | −0.15 | 0.26 | −0.01 | −2.20 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −2.00 | −0.65 | −2.65 | 1.20 | |

| 0.16 | 6.43 | −0.49 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 4.83 | −0.35 | −4.51 | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.14 | 1.11 | −0.01 | −3.31 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.24 | −0.65 | −2.89 | 1.16 | |

| 0.18 | 5.62 | −0.50 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 5.06 | −0.36 | −4.10 | −0.07 | −0.53 | −0.13 | 1.42 | −0.04 | −3.51 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.14 | −0.69 | −2.83 | 1.12 | |

| 0.22 | 4.50 | −0.51 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 5.44 | −0.38 | −3.22 | −0.06 | −1.98 | −0.10 | 0.50 | −0.06 | −2.62 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −2.35 | −0.68 | −3.03 | 1.06 | |

| 0.27 | 3.75 | −0.52 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 5.87 | −0.41 | −2.33 | −0.05 | −3.08 | −0.07 | −0.26 | −0.04 | −1.94 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −2.15 | −0.66 | −2.81 | 1.00 | |

| 0.31 | 3.21 | −0.53 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 6.30 | −0.43 | −1.66 | −0.04 | −4.15 | −0.05 | 0.14 | −0.05 | −2.33 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −2.24 | −0.67 | −2.90 | 0.95 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fadigati, L.; Gagliardi, M.D.; Sozio, E.; Rossi, F.; Souhair, N.; Ponti, F. Aerospike Aerodynamic Characterization at Varying Ambient Pressures. Aerospace 2026, 13, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010012

Fadigati L, Gagliardi MD, Sozio E, Rossi F, Souhair N, Ponti F. Aerospike Aerodynamic Characterization at Varying Ambient Pressures. Aerospace. 2026; 13(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleFadigati, Luca, Marco Daniel Gagliardi, Ernesto Sozio, Federico Rossi, Nabil Souhair, and Fabrizio Ponti. 2026. "Aerospike Aerodynamic Characterization at Varying Ambient Pressures" Aerospace 13, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010012

APA StyleFadigati, L., Gagliardi, M. D., Sozio, E., Rossi, F., Souhair, N., & Ponti, F. (2026). Aerospike Aerodynamic Characterization at Varying Ambient Pressures. Aerospace, 13(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010012