1. Introduction

The environmental impact of the international aviation industry is increasingly under public scrutiny, prompting airlines and aircraft manufacturers to prioritize sustainability in their strategic decisions. The sector’s contribution to climate change and other environmental challenges has become a prominent topic in public discourse [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Aviation is a highly energy-intensive sector. In 2024, global carbon dioxide (CO

2) emissions from air transportation increased by nearly 8%, reaching an estimated 882 million metric tons (Mt CO

2). This increase continues the upward trend observed since the significant reductions in 2020 caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Approximately 60% of these emissions are attributed to international flights [

5]. In addition to CO

2, aircraft engines emit other pollutants, including nitrogen oxides (NO

X), sulfur dioxide (SO

2), water vapor, and particulate matter such as sulfates and soot. When released at high altitudes, these emissions alter physical and chemical properties of the atmosphere, intensifying the greenhouse effect—one of the primary drivers of climate change. Moreover, these emissions can lead to the formation of persistent contrail cirrus clouds, which further contribute to global warming by trapping the Earth’s heat [

6].

To meet the objectives of the European Green Deal—aiming for climate neutrality in Europe by 2050—the aviation sector must transition toward hybrid-electric regional aircraft. Achieving this target requires a 90% reduction in transport-related emissions by mid-century compared to 1990 levels [

7]. This transformation necessitates the development of power distribution networks capable of safely managing high voltage and power levels, often reaching several megawatts. The EU-funded HECATE project addresses key challenges related to system weight, power density, high-voltage phenomena (such as lightning arcs and electromagnetic interference), and optimized thermal management. HECATE aims to develop a suite of enabling technologies and propose a scalability roadmap for CAJU Phase 2 flight demonstration, supporting the deployment of hybrid-electric regional aircraft by 2035 [

8].

In recent decades, the aerospace industry has experienced a profound structural transformation, increasingly embracing the More Electric Aircraft (MEA) concept [

9]. This paradigm shift is primarily driven by two interrelated imperatives: the urgent need to mitigate the environmental impact of aviation—particularly through the reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—and the economic pressure to enhance operational efficiency by lowering fuel consumption and maintenance costs.

The MEA architecture involves the progressive replacement of conventional mechanical, hydraulic, and pneumatic systems with electrically powered alternatives. This transition enables greater energy efficiency, reduced system complexity, and weight savings, all of which contribute to improved aircraft performance and sustainability. From an environmental perspective, MEA technologies support the broader decarbonization goals of the aviation sector, aligning with regulatory frameworks such as the European Green Deal and ICAO’s long-term aspirational targets.

Moreover, the electrification of subsystems—such as environmental control, actuation, and power distribution—paves the way for the integration of hybrid-electric and fully electric propulsion systems, which are expected to play a critical role in next-generation aircraft. This transformation represents a key enabler in achieving the aviation industry’s long-term objective of climate neutrality by mid-century.

Despite significant advancements, the implementation of MEA solutions still presents challenges related to system reliability, thermal management, and the environmental impact of electrical components. These challenges underscore the importance of comprehensive Life Cycle Assessment approaches to guide sustainable design and development. In parallel, contemporary aircraft design trends are shifting away from traditional mechanical systems—such as hydraulics and pneumatics—toward electrical components, particularly Aircraft Electrical Power Distribution Systems. These systems are responsible for the generation, regulation, and distribution of electrical power throughout the aircraft. The overall performance of modern aircraft is increasingly linked to the reliability and efficiency of these electrical systems and their subsystems [

9].

The Electrical Power System (EPS) plays a critical and multifaceted role within the overall system architecture. Its primary functions can be categorized into three core areas:

Power Supply: EPS is responsible for delivering electrical energy to both primary and secondary loads. Primary loads are associated with the propulsion system, secondary loads include various on-board systems such as avionics, thermal control, communication subsystems, and payload instrumentation.

Power Management and Distribution: A key function of the EPS is to efficiently manage the consumption of electrical power by regulating and distributing it across different system components.

Controllability, Fault Detection, and Protection: The EPS ensures system-wide controllability and enables continuous monitoring of its performance. It incorporates fault detection mechanisms and protective features that safeguard the system against potential electrical anomalies, including overvoltage, undervoltage, short circuits, and overloads.

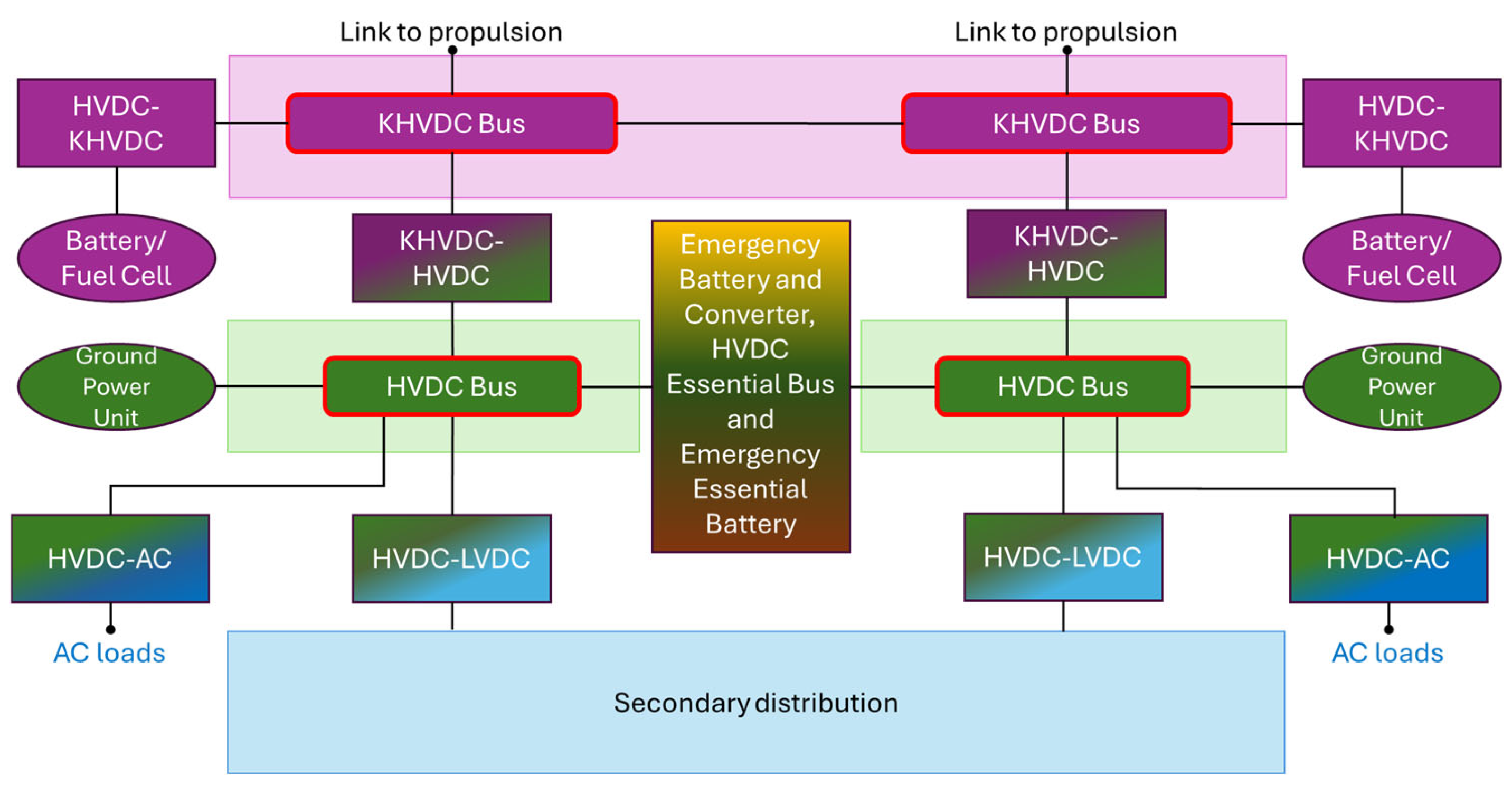

The electrical architecture of the HECATE system is organized into three dedicated subsystems. This modular structure enhances the system’s reliability, scalability, and ease of integration:

Primary Distribution for Propulsive Loads: This subsystem handles the delivery of high-power electrical energy required by the propulsion units. It is designed with a focus on robustness and redundancy, given the central importance of propulsion in achieving mission trajectory and maneuvering capabilities.

Primary Distribution for Non-Propulsive Loads: This segment supplies power to non-propulsive systems, including life-supporting and mission-critical subsystems. The separation of non-propulsive power distribution allows for targeted control and enhanced protection of sensitive components.

Secondary Distribution and Energy Conditioning Subsystem: This subsystem is responsible for fine-grained power regulation and conversion, interfacing with batteries, solar arrays, and power storage units. It ensures that power from variable sources is conditioned to meet the electrical specifications of downstream subsystems. Additionally, it manages charge and discharge cycles of energy storage units, optimizing longevity and performance.

The figure below shows a simplified schematic representation of the Electrical Power Distribution System architecture.

Overall, the EPS in the HECATE system is engineered to provide resilient, efficient, and adaptive electrical support. The Electrical Power System is composed of several key subsystems and components that are responsible for power generation, conversion, and distribution throughout the platform. The main elements of the EPS include the following:

The Electrical Power Source, which may consist of a Fuel Cell or a Battery Pack, serves as the primary source of electrical energy.

Emergency Battery Pack, which provides backup power in case of failure or disconnection of the main source, ensuring system reliability and continuity of operations.

KHVDC (Kilovolt High Voltage Direct Current) Buses, HVDC (High Voltage Direct Current) Buses, and LVDC (Low Voltage Direct Current) Buses, which serve as electrical distribution pathways operating at different voltage levels, optimized for power transfer efficiency and subsystem compatibility.

KHVDC-HVDC Converter, HVDC-LVDC Converter, Emergency Converter, and HVDC-AC Converter, which perform the necessary voltage level transitions and current type conversions to support the power requirements of various subsystems and to ensure interoperability across different power domains.

Solid State Power Controller (SSPC) Modules or SSPC Modules (SSPM), which are integrated within distribution boxes and play a critical role in switching, protecting, and monitoring power distribution lines using solid-state technology.

One of the primary advantages of advanced aircraft electrical power systems is the reduced weight, achieved by decreasing the usage of heavy gauge power feeders. This reduction in weight contributes significantly to the overall efficiency of the aircraft. Additionally, the total amount of power distribution wiring is minimized, further enhancing efficiency. Another benefit is the improved electronic control of load distribution throughout the aircraft, which enhances operational performance [

10].

However, these advanced systems also come with certain disadvantages. The complexity of electrical systems makes them more susceptible to electrical failures. The significant increase in power requirements poses potential dangers if malfunctions occur. Furthermore, the increased number of electrical circuits raises the probability of short circuits and power loss. Higher operating frequencies increase sensitivity to voltage drops, thereby elevating the risk of power loss.

This paper focuses on LCA analysis of the main components of the primary distribution system, namely KHVDC Bus and HVDC Bus (highlighted in red in

Figure 1). The critical components of KHVDC and HVDC Buses are electromechanical contactors, which have been optimized to be lighter and more compact in order to supply power to electrical propulsion units and high-power non-propulsive loads. State-of-the-art primary distribution systems based on electromechanical contactors are not suitable for the high-voltage and high-current conditions required by novel hybrid-electrical architectures. The main object of the presented LCA is the contactor, which can be described as an electromechanical switching device designed to control the flow of electricity in a circuit. A contactor performs the switching of a power circuit in a manner similar to a relay, however with significantly higher current ratings. A typical electromechanical contactor is built from the following components: (1) a coil incorporated to iron core, which generates a magnetic field when current flows through the coil; (2) contacts, which are current-carrying elements that make or break the electrical circuit and may include main (power) contacts or auxiliary (control) contacts; (3) an armature, which is actuated by the magnetic field to switch the contacts; and (4) an enclosure, which provides protection and electrical insulation for the internal components [

11].

Despite the growing importance of sustainable aviation technologies, the current literature lacks Life Cycle Assessment data for advanced primary electrical distribution systems based on contactor technologies developed for next-generation hybrid-electric aircraft. Furthermore, studies specifically addressing the LCA of individual electrical components, such as contactors, remain scarce.

LCAs of automotive electrical subsystems consistently show that the production phase—particularly the extraction and processing of copper and other metals—constitutes the principal environmental burden. For instance, in a recent cradle-to-gate LCA of a vehicle wiring harness, the authors report that raw material production accounts for more than 87% of overall environmental impacts, with copper-based wires representing the largest share [

12]. Additionally, a comparative LCA of a novel copper-tin alloy cable versus conventional copper cable demonstrates that a lighter, alloy-based cable can reduce environmental impacts by roughly 54% relative to the traditional solution.

Studies on power-electronic components also confirm that manufacturing devices such as inverters exerts substantial environmental pressure. In an LCA of a 150 kW traction inverter, the “busbar” and “DC-link capacitor”—both containing significant quantities of copper and other metals—emerge among the major contributors to resource depletion and other impact categories [

13]. The “power module” and aluminum casing further stand out as hotspots, emphasizing that both metal content and manufacturing processes critically influence overall impacts [

14]

These findings imply that, for electric vehicles, enhancing the recyclability of electrical components and increasing the share of recycled or secondary materials (e.g., recycled copper) may substantially reduce the life-cycle environmental footprint. Indeed, several authors suggest material substitution (copper alloys, lighter materials) and design for recyclability as promising strategies for eco-design of wiring harnesses and power electronics. A review of the existing literature reveals that LCA methodologies have predominantly been applied to widely used electronic devices, including personal computers [

15], electric motors [

16], and microprocessors [

17]. Only a limited number of manufacturers—such as ABB [

18], Schneider Electric [

19], and Siemens [

20]—have conducted environmental impact assessments for their contactors. These assessments are typically published in the form of Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) and report Global Warming Potential (GWP) values ranging from approximately 5 to 10.5 kg CO

2-equivalent per kilogram of contactor.

These EPDs, while informative, are not fully representative of contactors developed for aerospace applications, which often involve different design specifications, material compositions, and functional requirements. Consequently, a critical research gap remains in understanding the life cycle environmental impacts of high-performance, aerospace-grade contactors used in hybrid-electric propulsion systems.

The objective of the present study was to perform a comprehensive LCA of the main components of the primary distribution system in hybrid electric aircraft, such as electromagnetic contactors, with a focus on the manufacturing stage of the analyzed products. The study addresses the impact of materials, energy use, and transportation on the environmental performance of the contactors, as well as the contribution of the primary distribution system’s carbon footprint to the overall environmental profile of the energy distribution system in modern aircraft.

2. Methodology

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a science-based methodology used to evaluate the potential environmental impacts of products or services throughout their entire life cycle. This includes the assessment of natural resource use, raw material and energy consumption, and emissions to the environment (air, water, and soil) across all life-cycle phases of the system under study. Initially, all incoming and outgoing flows—both material and energy, whether extracted from or released into the environment—are inventoried for each phase. These flows are then aggregated to quantify environmental impact indicators. The results are expressed through a set of relevant environmental metrics.

LCA enables comparison between different scenarios and helps identify pollution transfers—referred to as “burden shifting”—either between types of environmental impacts or between life-cycle stages. This allows for the evaluation of trade-offs between alternatives, whether they pertain to the same system or different systems. As such, LCA is a valuable tool in “design for the environment” strategies and in supporting environmental decision-making processes.

All LCA studies should adhere to the internationally recognized ISO standards: ISO 14040:2006 (Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework) [

21] and ISO 14044:2006 (Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines) [

22].

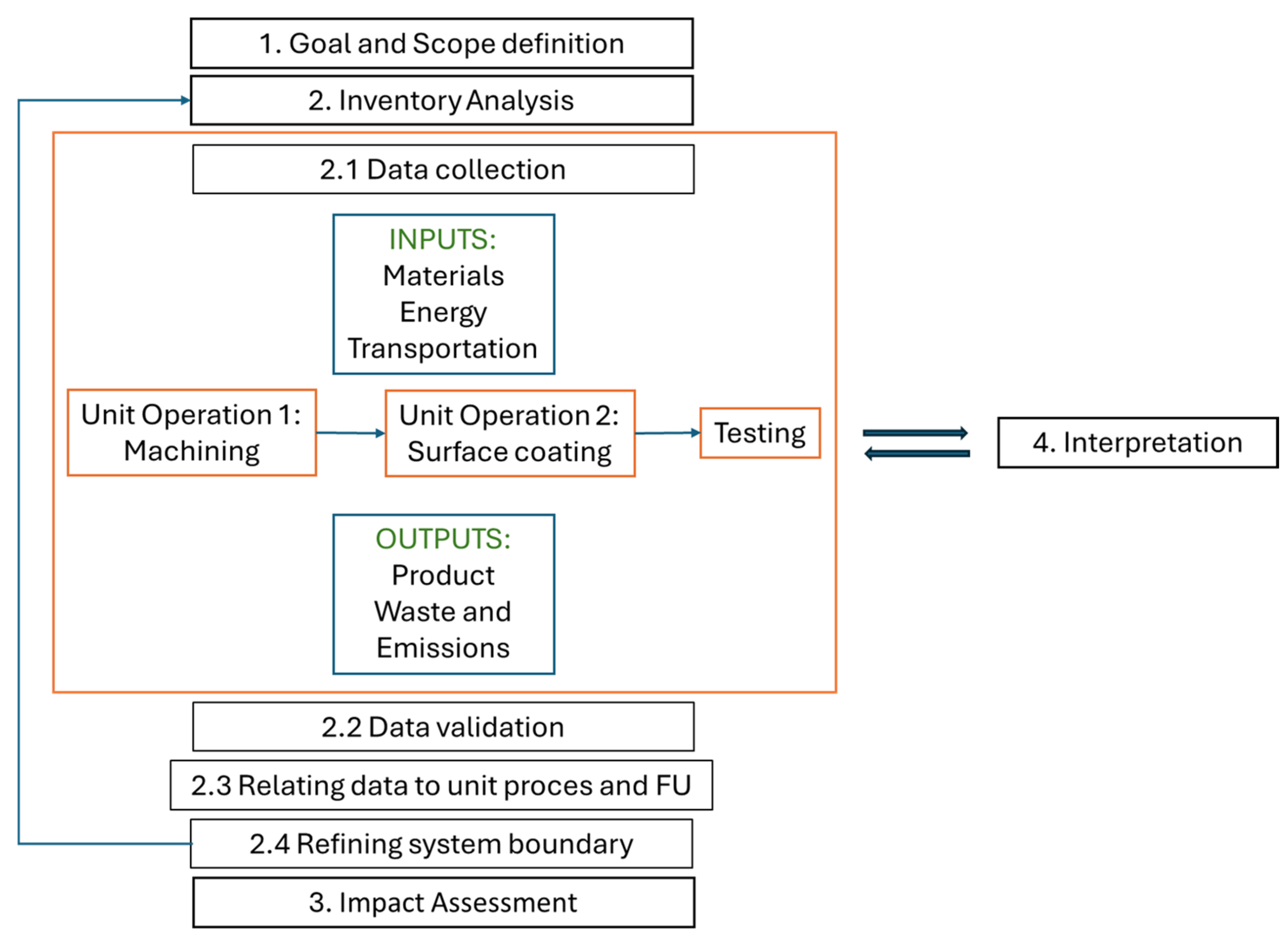

A comprehensive LCA, in accordance with the ISO 14040 series, consists of four interrelated phases:

Goal and Scope Definition: This phase defines the objective of the study and describes the product, process, or system being analyzed. It sets the context, outlines the system boundaries, and identifies the environmental impacts to be assessed. In this study, a Cradle-to-Gate approach was employed to evaluate the primary electrical power distribution system. This method covers the life cycle from raw material extraction (“cradle”) to the point at which the product exits the manufacturing facility (“gate”). The system boundaries include: raw material acquisition and processing, manufacturing (including energy and material use), and transport between production sites up to final assembly. Excluded from the scope are: waste disposal during production (provided in sensitivity analysis in the next section), downstream transportation, end-of-life (EoL) treatment, and the production, maintenance, and decommissioning of supporting infrastructure. A Cradle-to-Gate system boundary implies that the product use phase and the end-of-life stage are excluded from the scope of the analysis.

The functional unit (FU) used in this analysis is one primary distribution system capable of distributing electrical power for 2.0 MW propulsive network for a Hybrid Electrical Regional Aircraft.

- 2.

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis: This technical phase involves the identification and quantification of energy, water, and material inputs, as well as environmental outputs such as emissions, solid waste, and wastewater discharges. Data were collected using structured questionnaires distributed to project partners. In cases where primary data were unavailable, estimates were made based on literature reviews and expert input from HECATE partners. Allocation procedures followed the ISO 14044 guidelines and the GHG Protocol standards, particularly those related to product-level and Scope 3 value chain emissions. Specific Scope 3 categories were considered to ensure alignment with the various stages of the life cycle and to enhance methodological robustness.

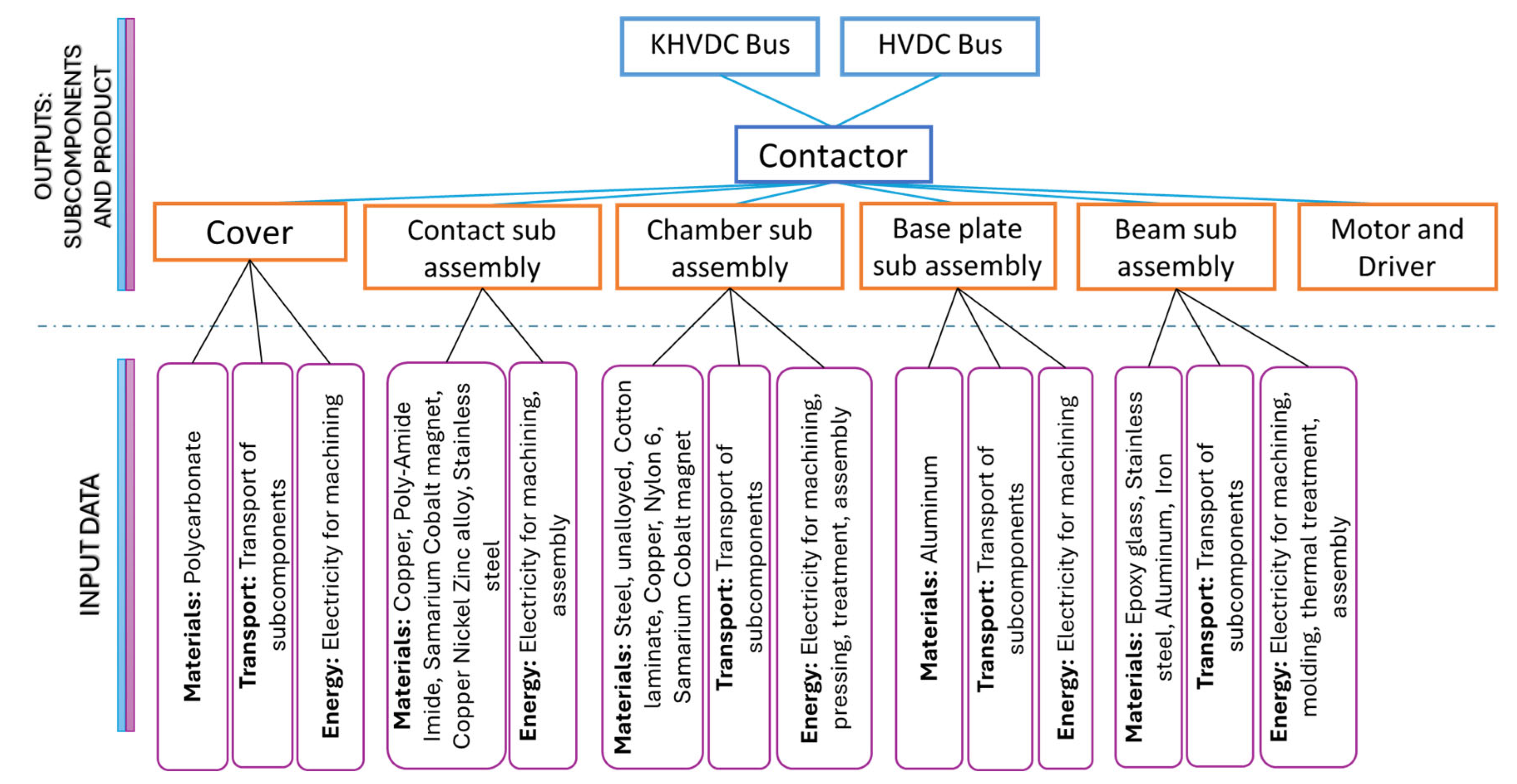

A schematic overview of the system’s inputs and outputs is shown in

Figure 2. Due to the system’s complexity, data for the Motor and Driver components are presented separately in

Figure 3. These data reflect the defined system boundaries and form the basis for the subsequent environmental impact assessment (detailed inventory tables are presented in

Supplementary Material).

The following assumptions were applied to convert the input data into a Life Cycle Inventory (LCI):

The printed circuit board (PCB) applied in the contactor is a Commercial Off-The-Shelf complex part which included 26 different components such as 5 diodes, 3 ceramic capacitors, 1 tantalum capacitor, glass passivated junction, 10 resistors, 2 surface mount fuse, diluent, 2 transistors surface mounted on FR4 base. Due to complexity, the exact weight of each component of PCB was not available, therefore PCB was calculated in the model using the Ecoinvent database entry “PCB, surface mounted, unspecified, Pb-free.”

The copper-nickel-zinc alloy was represented by the Ecoinvent dataset “Copper-rich material.”

The samarium-cobalt magnet was approximated using the Ecoinvent entry “Permanent magnet, for electric motor.”

- 3.

Impact Assessment: This phase evaluates the potential effects of energy and material usage, along with the environmental releases identified in the inventory analysis. It includes both mandatory and optional sub-phases—such as classification, characterization, normalization, and weighting—in accordance with ISO standards. Environmental impact categories and indicators must comprehensively address the relevant environmental issues associated with the system under study. This research assesses a selection of environmental impacts and characterization methods recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its 2021 Version 1.03 guidelines. The IPCC 2021 impact assessment method, which supersedes the IPCC 2013 method, incorporates Global Warming Potential (GWP) factors for climate change over a 100-year timeframe. The outcomes of this assessment are expressed in kilograms of CO

2 equivalent. The general and simplified mathematical formulation of applied LCA methodology may be presented in following equation:

where

LCIMaterials—Life Cycle Inventory for Materials in [kg] or [m3],

GWP FactorMaterials—Emission factor in [kg CO2-eq./kg] or [kg CO2-eq./m3],

LCIEnergy—Life Cycle Inventory for Energy in [kWh],

GWP FactorEnergy—Emission factor in [kg CO2-eq./kWh],

LCITransportation—Life Cycle Inventory for Transportation in [kg*km],

GWP FactorTransportation—Emission factor in [kg CO2-eq./kg*km],

GWP Total—total carbon footprint for Life Cycle Inventory.

- 4.

Interpretation: This final phase involves analyzing the results of the inventory analysis and impact assessment to identify the preferred product, process, or service. It requires a clear understanding of the uncertainties and assumptions underlying the results.

This structured approach ensures that the LCA provides a robust and scientifically sound foundation for decision-making and environmentally conscious design.

By following this methodology (

Figure 4), the LCA provides a thorough evaluation of the carbon footprint of the primary distribution system, offering insights into areas for improvement and strategies for enhancing sustainability.

3. Results and Discussion

The inventory analysis constitutes a critical phase of the Life Cycle Assessment, directly influencing the accuracy and reliability of the results. In this study, life cycle inventory tables for each of the analyzed component of the primary electrical distribution system were continuously refined and critically evaluated in collaboration with industrial partners. This iterative process ensured the inclusion of up-to-date and representative data that reflect current industrial practices.

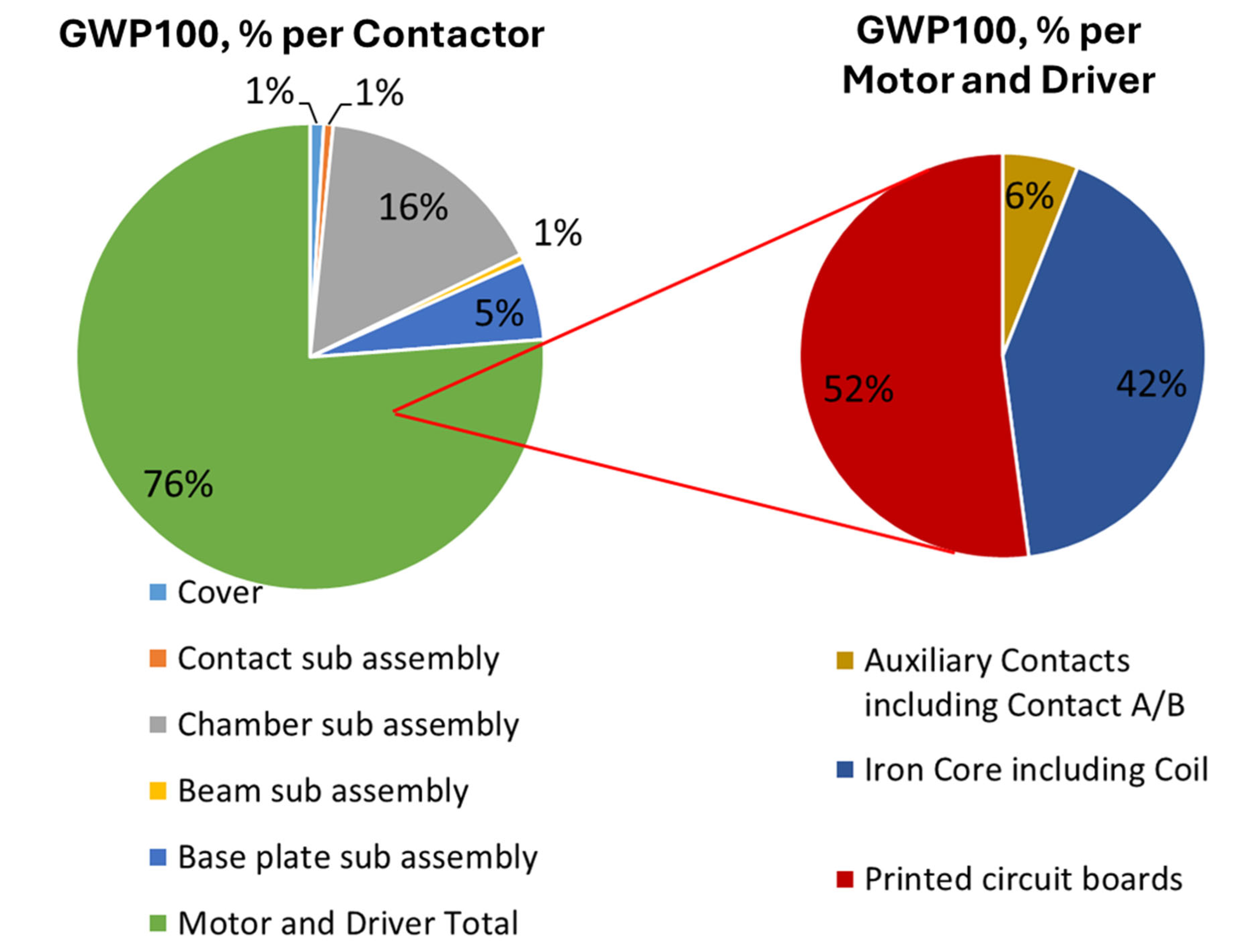

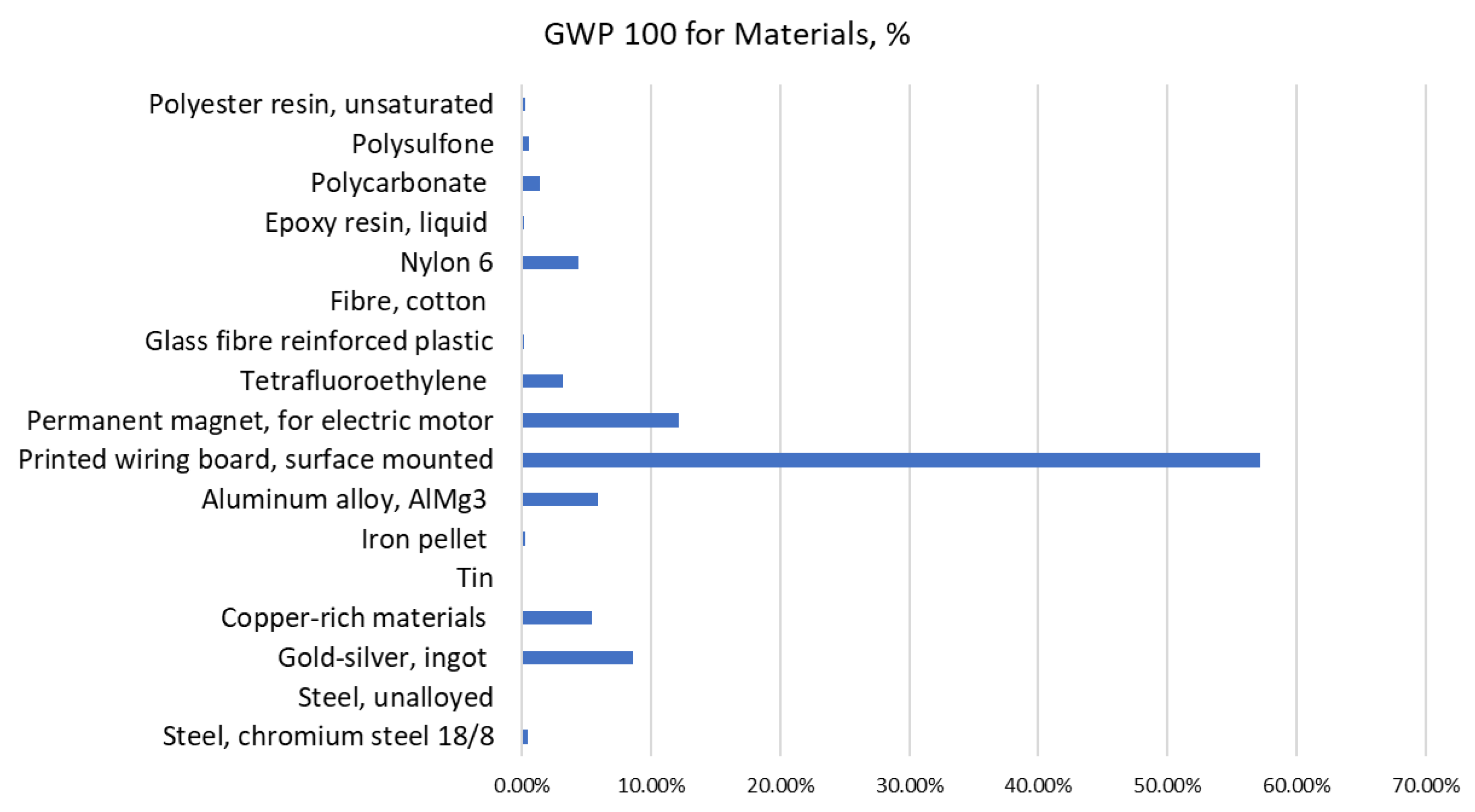

The finalized inventory tables, developed through this rigorous approach, provided a robust foundation for accurate LCA calculations of the electrical distribution system. The LCA results, expressed in terms of Global Warming Potential over a 100-year time horizon (GWP100), were first calculated for each individual component of the contactor and subsequently aggregated to represent the impact per single contactor unit (as presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2). The contribution of each component to the carbon footprint is also illustrated in

Figure 5.

To estimate the total environmental impact of the KHVDC and HVDC Buses, the carbon footprint per contactor must be multiplied by the number of contactors integrated into each system. According to the system design, fulfilling the functional unit requires a total of 16 contactors for the two KHVDC Buses and 10 contactors for the two HVDC Buses.

Table 1 presents the results of the environmental impact assessment for individual components within the Motor and Driver sections of the contactor. The dominant contribution to the overall carbon footprint of each subcomponent originates from raw material extraction and manufacturing processes. In contrast, the influence of transportation on total emissions is negligible, accounting for less than 1% of the total impact for each part.

The highest CO

2 emissions were associated with the printed circuit board (PCB), amounting to 10.41 kg CO

2-eq. per unit, followed by the iron core with coil, generating 8.39 kg CO

2-eq. per unit. These findings are consistent with previous studies [

23], which reported that PCBs contribute approximately 49% of the carbon footprint during the manufacturing phase of a smartphone—representing the most significant impact among all components. The obtained results are also in agreement with the work of Zhang et al., who reported that Flame Retardant 4 (FR4), the main component of PCBs, has the most significant contribution to the environmental impact of a TV remote control [

24].

PCBs serve as essential structural and electrical platforms that interconnect electronic components in virtually all modern electronic devices. Their manufacturing involves a sequence of energy- and material-intensive steps, including:

- (1)

stack-up design (arrangement of conductive and dielectric layers),

- (2)

core engraving,

- (3)

lamination (a highly energy-intensive process),

- (4)

electrolytic copper deposition,

- (5)

photoengraving of outer layers,

- (6)

encapsulation for insulation and mechanical protection, and

- (7)

Accurately quantifying the carbon footprint of a PCB is inherently challenging due to a wide array of influencing factors, such as board type (e.g., surface-mounted vs. through-hole mounted), number of layers, manufacturing techniques, and the complexity and diversity of embedded components [

26]. Consequently, life cycle assessments based on various matches from the Ecoinvent 3.11 database yield a broad range of carbon footprint values, typically ranging from approximately 55 to 376 kg CO

2-eq. per kilogram of PCB material.

For the contact components A and B, materials account for approximately 69% of the total CO2 emissions, primarily due to the use of high-impact metals such as silver and gold. In the case of the coil, the contribution of materials to the production-phase emissions is even more pronounced, reaching 88%, with copper and tetrafluoroethylene identified as the main contributors to the environmental burden.

In contrast, the coil integrated into the iron core exhibits a markedly different emissions profile. In this case, only 18.5% of the total carbon footprint arises from the materials used, while nearly 82% results from the energy-intensive surface coating process applied to iron components. This treatment is carried out at elevated temperatures—approximately 850 °C—over a prolonged duration of around 14 h, leading to substantial electricity consumption and, consequently, high associated greenhouse gas emissions.

These findings highlight the significance of both material selection and energy consumption in thermal processing stages, particularly for components requiring metallurgical surface modifications. The results emphasize the need for targeted improvements in material efficiency and process optimization to reduce the environmental footprint of high-performance electrical distribution components.

Table 2 presents the results of the environmental impact assessment for the remaining components of the contactor, as well as the overall carbon footprint of the contactor assembly. Within the contact subassembly, the materials used accounted for the majority of the impact, contributing approximately 92% of total emissions, with copper identified as the primary contributor. For the chamber subassembly, the main material-related sources of CO

2 emissions were the magnet and nylon 6. Notably, transportation accounted for 17.81% of the total emissions associated with this subassembly, reflecting the inclusion of long-haul air freight in its supply chain. In the beam subassembly, stainless steel and epoxy resin were the dominant contributors to the overall CO

2-equivalent emissions.

Figure 6 illustrates the relative contributions of various materials used in the manufacturing of the contractor to its overall environmental impact. The printed circuit board (PCB) accounts for over 50% of the total material-related carbon footprint, followed by magnets at approximately 12%, precious metals (gold and silver) just under 9%, and copper, contributing more than 5%. According to the literature, samarium-cobalt magnets exhibit a substantial carbon footprint of approximately 66 kg CO

2-eq. per kilogram, primarily due to the energy-intensive extraction and processing of rare earth elements such as samarium and cobalt [

27]. Although the contactor manufacturing process uses only about 70 mg of precious metals (gold and silver), representing a mere 0.014% of the final product mass, these metals contribute disproportionately to the carbon footprint, accounting for nearly 9% of total emissions. This disproportionate impact arises from the inherently high greenhouse gas emissions associated with the gold and silver production. For example, gold production alone is estimated to generate approximately 12,200 kg CO

2 eq. per kilogram [

28]. These emissions results from energy-intensive mining and refining operations, including extensive use of heavy machinery, high ore-processing energy requirements, and the release of potent greenhouse gases such as methane during mining activities.

Among the polymers evaluated, nylon 6 (polyamide 6) and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) exhibit the highest carbon footprints. Nylon 6 is characterized by a notably high environmental impact among fossil fuel–derived polymers, with an estimated carbon footprint of approximately 9 kg CO

2 eq. per kilogram [

29]. This elevated footprint can be attributed to its production process, which relies on petrochemical feedstocks such as benzene or cyclohexane. The synthesis involves energy-intensive chemical reactions, notably the ring-opening polymerization of ε-caprolactam, which requires significant thermal and catalytic inputs. Additionally, upstream processes including raw material extraction, purification, and intermediate synthesis further contribute to the overall greenhouse gas emissions associated with nylon 6 production.

In comparison, PTFE also demonstrates a substantial carbon footprint, largely due to the energy-intensive fluorination processes and the use of fluorinated precursors, which are associated with both high embodied energy and potential environmental concerns related to fluorinated greenhouse gases [

30].

Overall, the significant environmental burdens of these polymers highlight the importance of considering material selection and process optimization in the design of components where polymers play a critical role.

For life cycle assessment (LCA) of complex products such as electrical equipment, it is important to perform a sensitivity analysis, as it can indicate which parameters have the greatest influence on the model or help identify insensitive parameters that do not significantly affect the output. Since the printed circuit board (PCB) contributes the most to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in contactors, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine how different Ecoinvent database entries impact the calculation results (

Table 3). The analysis evaluated how the selection of various PCB-related datasets from the Ecoinvent database influences the calculated Global Warming Potential (GWP100) per single contactor unit. The results demonstrate a notable variation in GWP values depending on the specific dataset used, with results ranging from 1.66 kg CO

2-eq. to 10.41 kg CO

2-eq. per part—a more than 6-fold difference. The substantial differences in CO

2 emissions for PCBs may be attributed to the type of technology used during their manufacturing. The first two rows in

Table 3 refer to PCBs produced using wave soldering and through-hole mounting technology, in which component leads are inserted into holes in the PCB and molten solder flows over the underside of the board, bonding to both the leads and the walls of the through-holes [

31]. The third entry in

Table 3 also represents a through-hole technology PCB. The final row, which shows the highest carbon footprint, corresponds to a PCB manufactured using surface-mount technology (SMT). In SMT, the PCB is coated with solder paste, components are placed by precision machines, and the solder is solidified in an oven. This approach enables higher component density and double-sided assembly. Consequently, the high carbon footprint observed for SMT PCBs can be explained by the more energy-intensive soldering process, the greater raw material demand for solder production, and the higher concentration of electronic components per unit mass of PCB.

Although the treatment of production waste was not included within the system’s boundaries, a sensitivity analysis was carried out to determine the extent to which end-of-life processing of this waste might affect the overall outcomes. The results of the carbon footprint analysis for the end-of-life stage of production waste are presented in

Table 4. Additionally, data on the weight of each waste fraction generated during the contactor manufacturing process is provided. In the applied end-of-life scenario, it was assumed that all production waste material flows are directed to incineration. The analysis shows that the carbon footprint from waste treatment accounts for only 0.23% of the total GWP100 value of the primary distribution system, which can be considered insignificant.

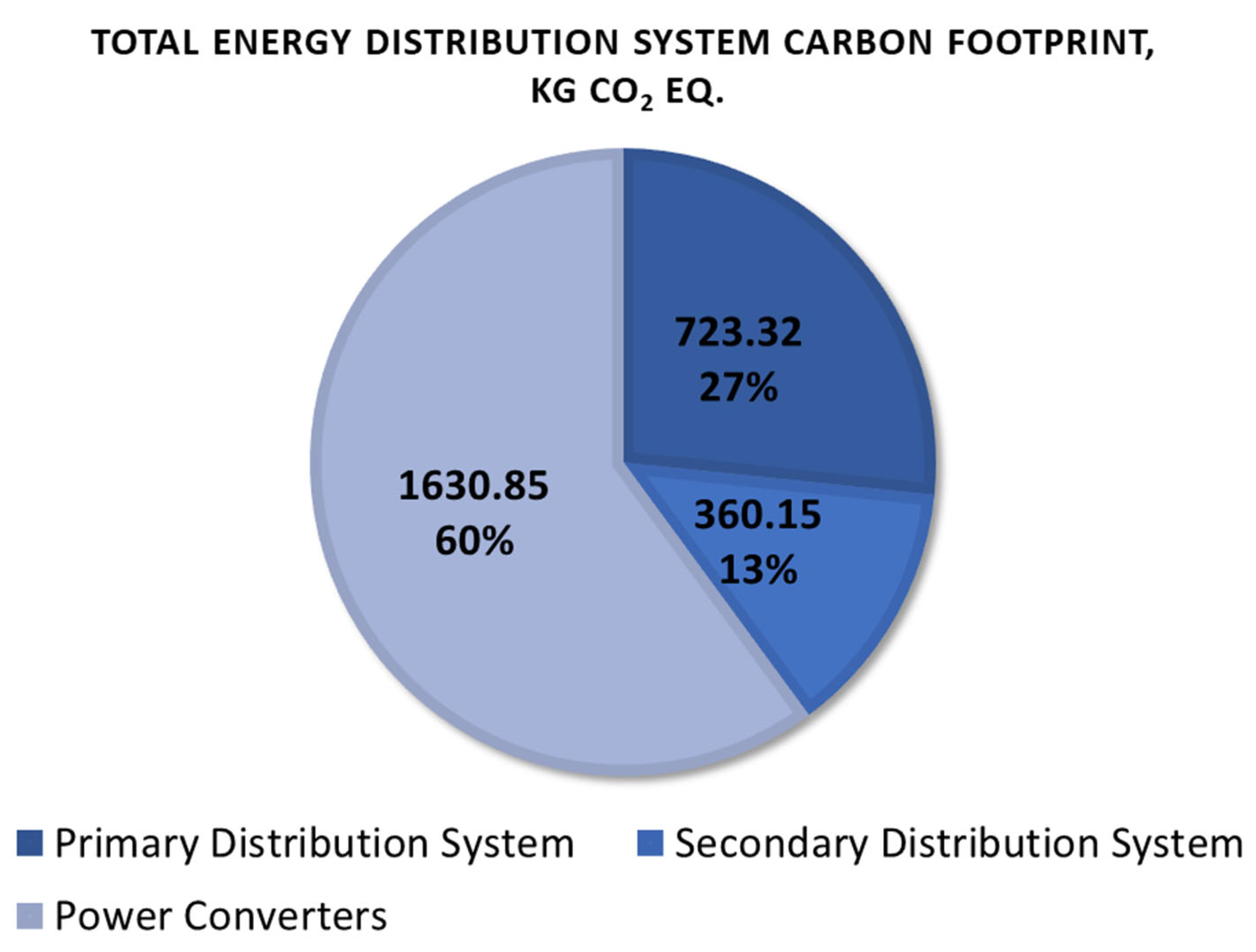

The primary objective of this study was to assess the relative environmental impact of the primary energy distribution system within the broader context of the entire electrical power system architecture of a modern hybrid-electric aircraft.

Figure 7 illustrates the share of the primary distribution system in the total greenhouse gas emissions (expressed as CO

2 equivalents) associated with the full energy distribution architecture. The analysis reveals the extent to which this subsystem influences the environmental performance of next-generation aircraft power systems, where weight reduction, material selection, and energy efficiency are key design drivers. Understanding the environmental role of each subsystem—particularly one as functionally critical as the primary distribution system—is essential for guiding future developments toward more sustainable aerospace technologies.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a detailed LCA of the primary electrical distribution system used in hybrid-electric aircraft, focusing on identifying the key contributors to the system’s overall environmental impact. The iterative development of detailed and critically reviewed life cycle inventory tables, carried out in collaboration with industry partners, enabled a high level of accuracy in quantifying the carbon footprint of individual contactor components. The results, expressed in terms of Global Warming Potential over a 100-year time horizon (GWP100), reveal that the printed circuit board is the most environmentally impactful component, contributing over 50% of the total carbon footprint per contactor. This finding is closely linked to the inherently energy-intensive nature of PCB fabrication, which involves multilayer lamination, high-temperature curing, and precision etching processes, as well as the use of composite materials such as epoxy resins, fiberglass, and copper foils—each of which carries a substantial upstream emissions burden. The analysis also confirms that several additional components exert disproportionate environmental impacts relative to their mass. Among them, samarium-cobalt magnets emerge as a major contributor due to the carbon-intensive mining and metallurgical processing of rare-earth elements. Precious metals, particularly gold and silver, similarly exhibit high emissions intensities, reflecting the energy demands and low ore grades inherent to their extraction and refining. Copper, although more abundant, adds significantly to the overall footprint because of the large quantities used in coils and conductive elements and the substantial energy required for its smelting and purification.

Material-related emissions dominate the environmental profiles of most subassemblies, particularly for the contact and coil components, where raw materials account for up to 88% of the carbon footprint. However, process-related emissions can also be substantial, as demonstrated by the iron core coating stage, where prolonged high-temperature treatment results in 82% of the total emissions for that component.

Additionally, the analysis highlights the disproportionately high environmental burden of small quantities of critical materials—such as precious metals and fluorinated polymers—due to their intensive production pathways. Gold, for example, although present in minimal amounts (0.014% of the product mass), contributes nearly 9% to the total emissions. For gold, the most effective approach involves minimizing the required plating thickness and limiting the number of gold-coated contact surfaces without compromising electrical reliability. The adoption of high-efficiency deposition processes, which reduce material losses during electroplating, further lowers the associated emissions. In parallel, increasing the share of secondary (recycled) gold in the supply chain can significantly reduce GWP, as the carbon intensity of recycled precious metals is substantially lower than that of primary extraction.

Similarly, polymers such as nylon 6 and PTFE exhibit high GWP values, resulting from their fossil-based origins and energy-intensive synthesis routes. For polymers, emission reductions can be achieved through substitution with lower-impact engineering plastics or modified grades with reduced energy requirements during synthesis, provided that thermal and dielectric performance remains compliant with aerospace specifications. In cases where substitution is not feasible, redesigning the affected parts to reduce polymer mass—such as optimizing geometries or integrating multi-functional features—can directly lower their contribution to the overall impact. Together, these targeted measures address the specific high-emission pathways identified in the study and offer practical routes for reducing the environmental footprint of the components without compromising system performance.

Looking ahead, several opportunities exist to reduce the environmental footprint of the system. Material substitution represents a key area of potential improvement—for example, replacing high-impact polymers with lower-carbon alternatives, adopting recycled metals where feasible, or integrating bio-based or recyclable composites. Additionally, optimization of thermal and surface treatment processes, including reducing processing temperatures, shortening treatment times, or utilizing renewable electricity, could substantially lower emissions associated with metallurgical components.

From a design perspective, increasing component modularity, simplifying assembly, and improving the recyclability of electronic and metallic subassemblies can support circularity and reduce end-of-life impacts. For PCBs, future steps should focus on minimizing layer count, adopting low-energy manufacturing methods, and exploring innovative board materials with reduced environmental burdens. Moreover, transportation, while generally a minor contributor, can become significant when globalized supply chains involve long-haul air freight, as observed in the chamber sub-assembly.

Overall, the findings underscore the importance of targeted material and process innovations, improved data quality, and holistic design strategies. These steps are essential for advancing the sustainability of future aerospace electrical systems and aligning next-generation aircraft technologies with long-term environmental objectives.

In addition to the conventional Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) approach applied in this study, advanced computational methods such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) offer promising avenues for further analysis. These techniques can enhance the handling of complex datasets, enable predictive modeling, and identify correlations between design parameters, material choices, and environmental impacts. AI and ML could also support the estimation of missing inventory data, detection of environmental hotspots, and optimization of system design for reduced carbon footprint. Incorporating these methods in future research may significantly improve the efficiency and precision of parametric LCA studies.