1. Introduction

The 2023–2032 “Origins, Worlds, and Life” Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey (OWL) [

1] has recommended a Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission (UOP) [

2] as the highest-priority concept for a new Flagship mission for planetary science and exploration. First discussed in the previous decadal survey [

3], the current decadal suggests that the Uranus Orbiter should launch in the early 2030s, indicating a bold plan that will require out-of-the-box thinking to become successful.

The initial UOP proposal submitted in support of the decadal survey describes a 7200 kg spacecraft to be launched in the early 2030s with a 13-year transfer time along an Earth-Earth-Jupiter-Uranus trajectory and a 4.5 year science mission phase [

2]. The multiple flyby maneuvers would lead to an arrival time of around 2044. This early 2030s launch time frame is becoming increasingly unlikely considering that the launch date is seven years away as of the writing of this paper. However, there are different ways in which we could launch a mission in such a compressed timeline. If the mass of the spacecraft is reduced or the excess energy of the launch vehicle is increased, alternate trajectories become possible. This is because if the launch vehicle has more energy than what is required to place a payload on a certain escape trajectory, it is possible to use that excess energy to turn the orbit into a hyperbolic trajectory, reaching other planetary bodies faster and with higher velocities. This reduces the spacecraft’s fuel requirements, which allows for more aggressive maneuvers further from Earth. Such accelerated trajectories have historical precedent: Voyager 2 reached Uranus approximately 8 years after launch [

4], and New Horizons passed Uranus’s orbit just over 5 years after launch [

5,

6].

In addition to accelerating the transfer time, more direct trajectories also result in fewer maneuvers and thus in a lower complexity and risk for the mission. A shorter transfer time also allows for a longer science mission phase, as the spacecraft will have spent less time in space when it arrives at its destination, decreasing the hardware degradation accumulated before the start of the actual mission. There are also marked scientific benefits to arriving at Uranus faster. The unique axial tilt of Uranus results in a long seasonal pattern: it takes 84 years for Uranus to complete one full cycle from southern solstice to equinox to northern solstice to equinox, and back to southern solstice [

7]. From approximately 2020 until approximately 2040, the northern hemisphere will be facing sunlight while the southern hemisphere will be in darkness [

8], heading into an equinox in 2049 [

9]. Arriving around 2040 would make the spacecraft a spectator of the change from solstice to equinox, allowing us to observe the transition between seasons and providing unique insights that may be lost if the spacecraft were to arrive after the transition had already taken place. In case an Uranus Flagship mission doesn’t become possible for a planetary arrival at or before the upcoming equinox, we believe there is a possibility that a lower-budget pathfinder mission—such as the one described here—could launch in the early 2030’s and support the flagship UOP by collecting data ahead of the Flagship. While the mission proposed here would not completely replace the UOP, it could be a promising contingency option that captures the Uranian behavior in a unique solstice-to-equinox transition while staying under a cost cap significantly lower than that of typical flagship missions. It would also have a shorter mission development timeline, potentially allowing for the early 2030s launch window.

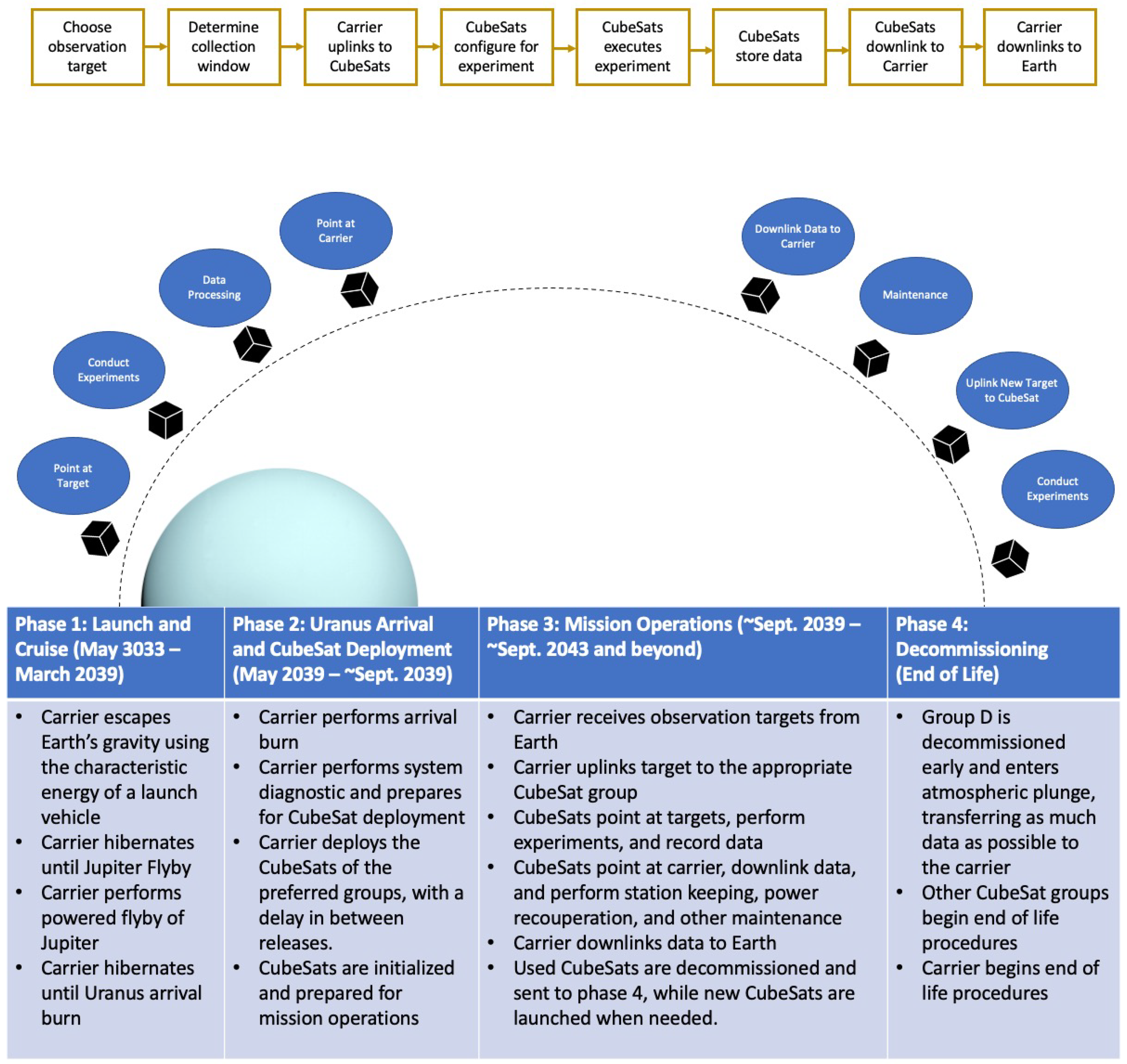

With the goal of answering as many questions from the OWL as possible, our new mission concept to Uranus would be able to supplement and provide bounding measurements ahead of the data collected by the initially proposed UOP spacecraft. Of the twelve thematic questions posed by the most recent decadal, UOP seeks to at least partially address eleven, answering questions about origins, processes, habitability, and interconnection. Of particular interest are the questions about how ice giants like Uranus form, what external factors are altering the planet, satellites, and ring compositions, and what interior structure produces Uranus’s complex magnetosphere. With the goal of supporting the Flagship mission, we propose a constellation of CubeSats be flown to Uranus at an accelerated timeline via a carrier spacecraft, allowing a glimpse into the Uranian system before it enters into equinox.

Despite these ambitious plans, many of the instruments proposed here have space heritage onboard observation satellites, and even CubeSats. The UOP orbiter plans to carry a Magnetometer, a variety of visible and IR cameras, a Spectrometer, a Fields & Particle Suite, and a Radio Science suite. The UOP probe plans to carry an Atmospheric Structure Instrument, a Mass Spectrometer, an UltraStable Oscillator, and a Hydrogen Sensor. Many of these instruments are or can be made relatively light, and even the heavier instruments, such as the spectrometers, have new, miniaturized versions being released [

10].

It is important to note that, although challenging, formation flights among multiple spacecraft have been successfully performed in the past [

11]. One example is the GRACE mission, which used two spacecraft to perform precise measurements of the gravitational potential of the Earth [

12]. Other examples are the DICE mission, which used two CubeSats in formation to measure ionospheric plasma density and magnetic fields [

13], the AeroCube-4 mission, which was composed of three CubeSats and demonstrated changes in orbital position between themselves [

14], ESA’s Cluster II mission, which uses four spacecraft in formation to study Earth’s magnetic field [

15], and the Magnetospheric Multiscale mission (MMS), which also studies Earth’s magnetic field and its interactions with the Sun [

16]. It is also important to note that other missions composed of CubeSats with a carrier spacecraft have been proposed, such as the CROWN Near-Earth Asteroid Surveillance Constellation [

17].

In addition to the unique benefits of CubeSats, there are also unique challenges. These challenges primarily stem from the difficulty of designing CubeSats to be used in deep space due to their small size. However, with current and emerging technologies, there are ways in which deep space CubeSats can be successful, as demonstrated by the MarCO [

18], the LICIACube [

19], and the CAPSTONE [

20] missions. In the following sections of this paper, we will discuss the goals of the proposed mission and how the technical challenges of the proposed CubeSat constellation can be solved.

2. Methods for Trajectory Generation

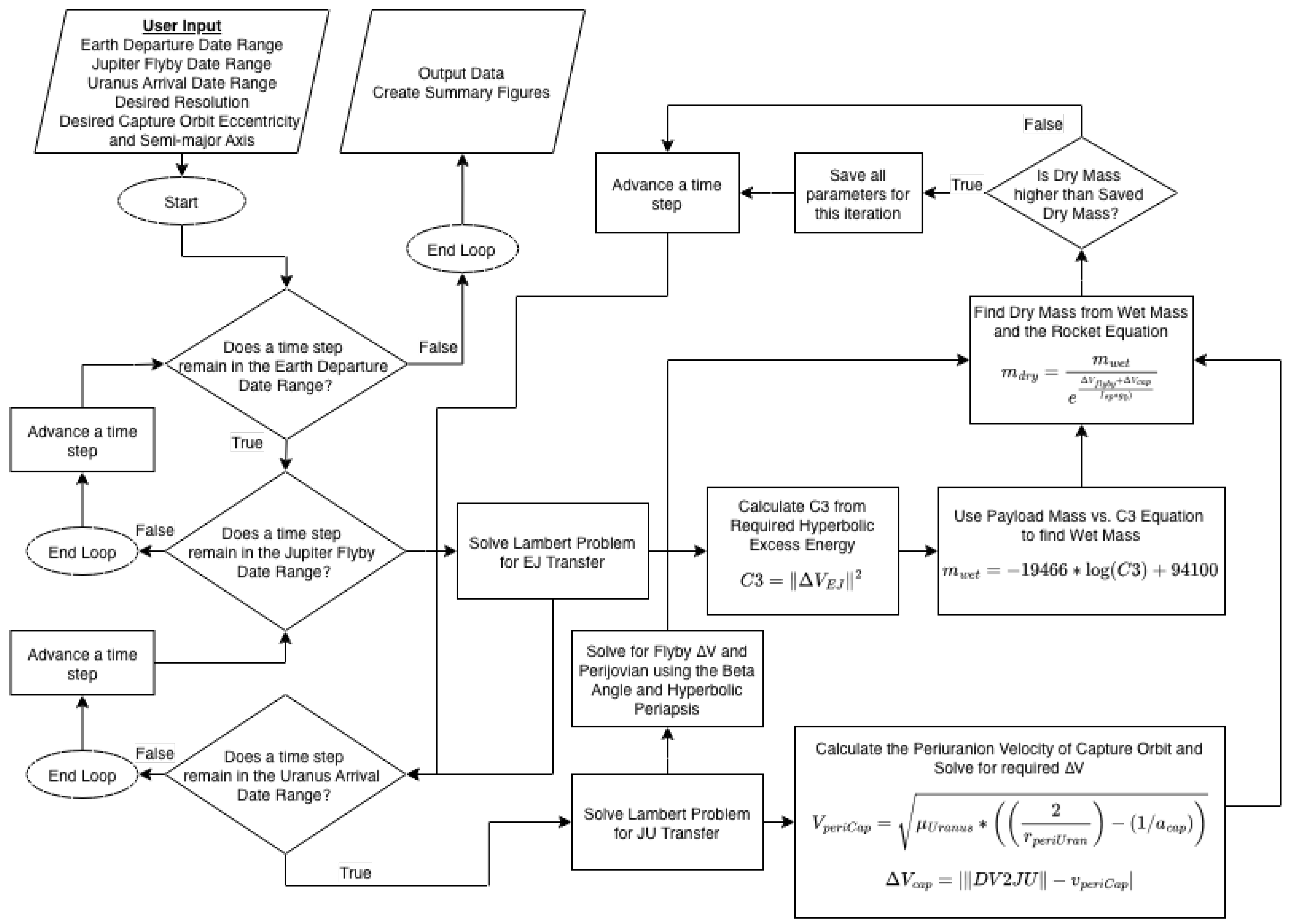

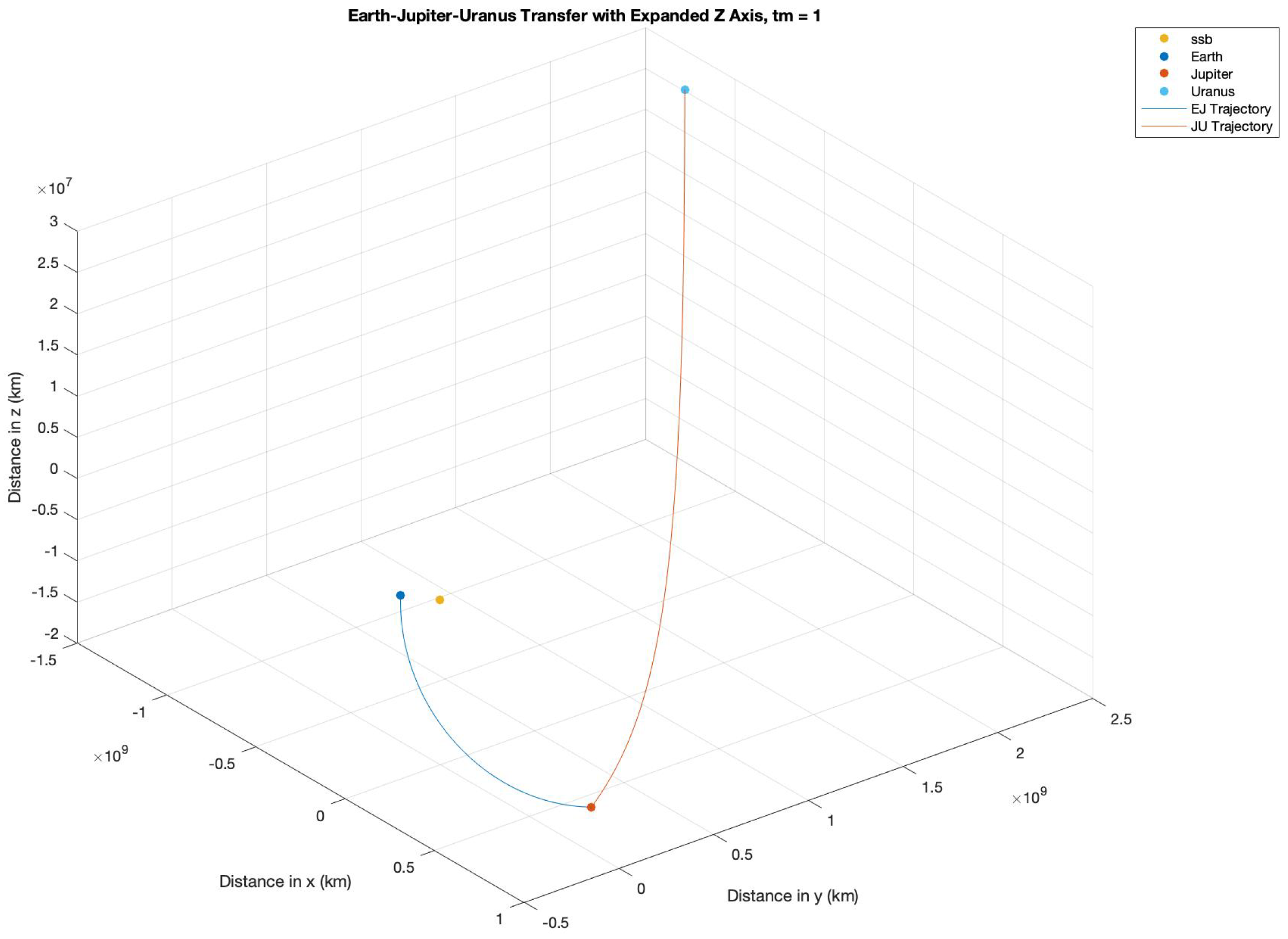

The interplanetary trajectories presented in this paper were generated through a MATLAB script that used the method of patched conics, Lambert’s problem, ref. [

21] and planetary ephemeris data from the NASA/Caltech Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Horizons database [

22]. To operate the script, a user must input their desired range of dates for launch, Jupiter flyby, and Uranus arrival. The script references the ephemerids of Earth, Jupiter, and Uranus for those dates and calculates numerical solutions to Lambert’s problem for each date combination. This generates the initial and final state vectors of a trajectory that achieves the desired transfer between the different planetary spheres of influence.

Next, the script calculates the necessary powered Jupiter flyby for each date combination, connecting the ending state vectors of the first Lambert transfer and starting state vectors of the second Lambert transfer. This step returns both the required and the hyperbolic perijovian where the burn would take place. In the final calculation, the script determines the required retrograde burn to enter a stable Uranus capture orbit for each date pair trajectory, given a user-supplied periuranion and orbital eccentricity, using the vis-viva equation and the definition of elliptical orbits.

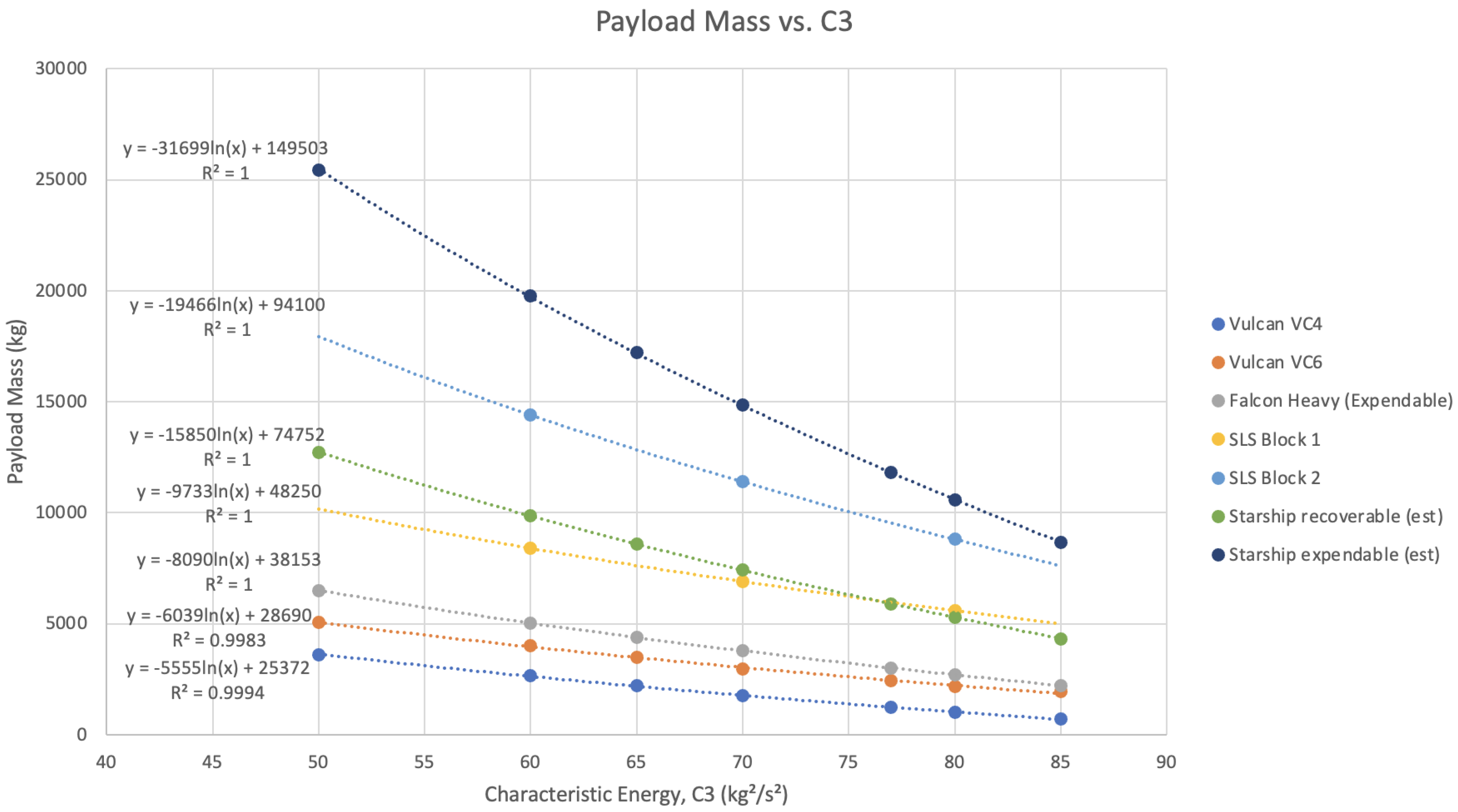

As the script supplies the necessary hyperbolic excess energy for a given trajectory, we are able to calculate the required characteristic energy (C3) that the launch vehicle must impart to the spacecraft. By only using the launch vehicle to supply the C3, we are able to save fuel mass and volume on the spacecraft itself. This C3 allows for the calculation of the maximum feasible wet mass of the spacecraft by using the capabilities of the launch vehicle. The relationship between maximum payload mass and C3 can be seen in

Figure 1 for a variety of different launch vehicles.

These data are available on the public NASA Launch Services Program Performance Website [

23]. Payload mass-to-orbit curves are not publicly available for Starship, so values were approximated based on Falcon Heavy characteristics and comparative lift to LEO.

The maximum mass allowance can then be used to find the required fuel mass for all other necessary

s. By using the rocket equation, we are able to calculate the ratio of wet mass to dry mass, which we can then use to find the maximum allowable dry mass for the spacecraft, and therefore obtain the required fuel mass. This allows for a realistic constraint when designing the payload and bus. The script calculates this information for all possible date combinations and then outputs the solution that maximizes the dry mass of the spacecraft, as well as figures that provide a visual summary. Example of these figures are Figures 4 and 5. A block diagram visualization of the script can be seen in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

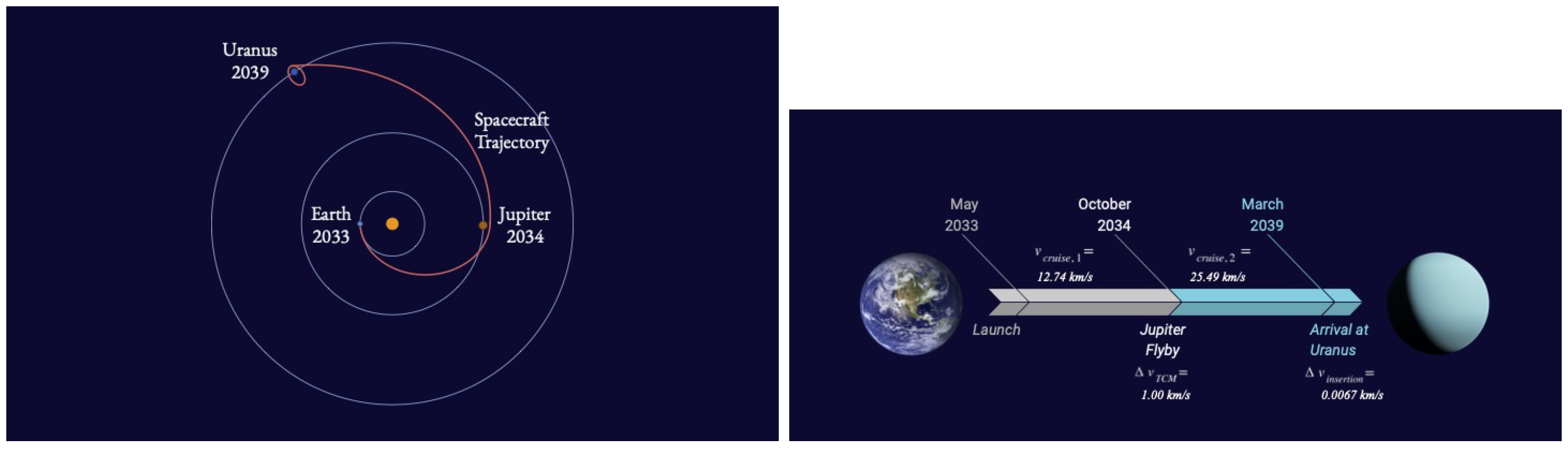

This work demonstrates that a CubeSat constellation mission to Uranus is likely a viable solution for answering many aspects of the 2023–2032 Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey’s thematic questions and can support the UOP by collecting data that the UOP cannot. We have shown that there is a unique scientific benefit to launching a lighter spacecraft on a lower fuel and cruise time trajectory, arriving at Uranus in around six years so that we can observe the shift from the northern solstice to the equinox and thus observing a planet wide change in climate. Arriving in time to observe such phenomenon is only possible with an early launch date, efficient flyby strategies, and a low spacecraft mass—all of which are crucial features of the mission we are proposing here. This timeline acceleration also results in a mission with lower complexity, lower personnel upkeep costs, and more potential of high-return scientific mission extensions.

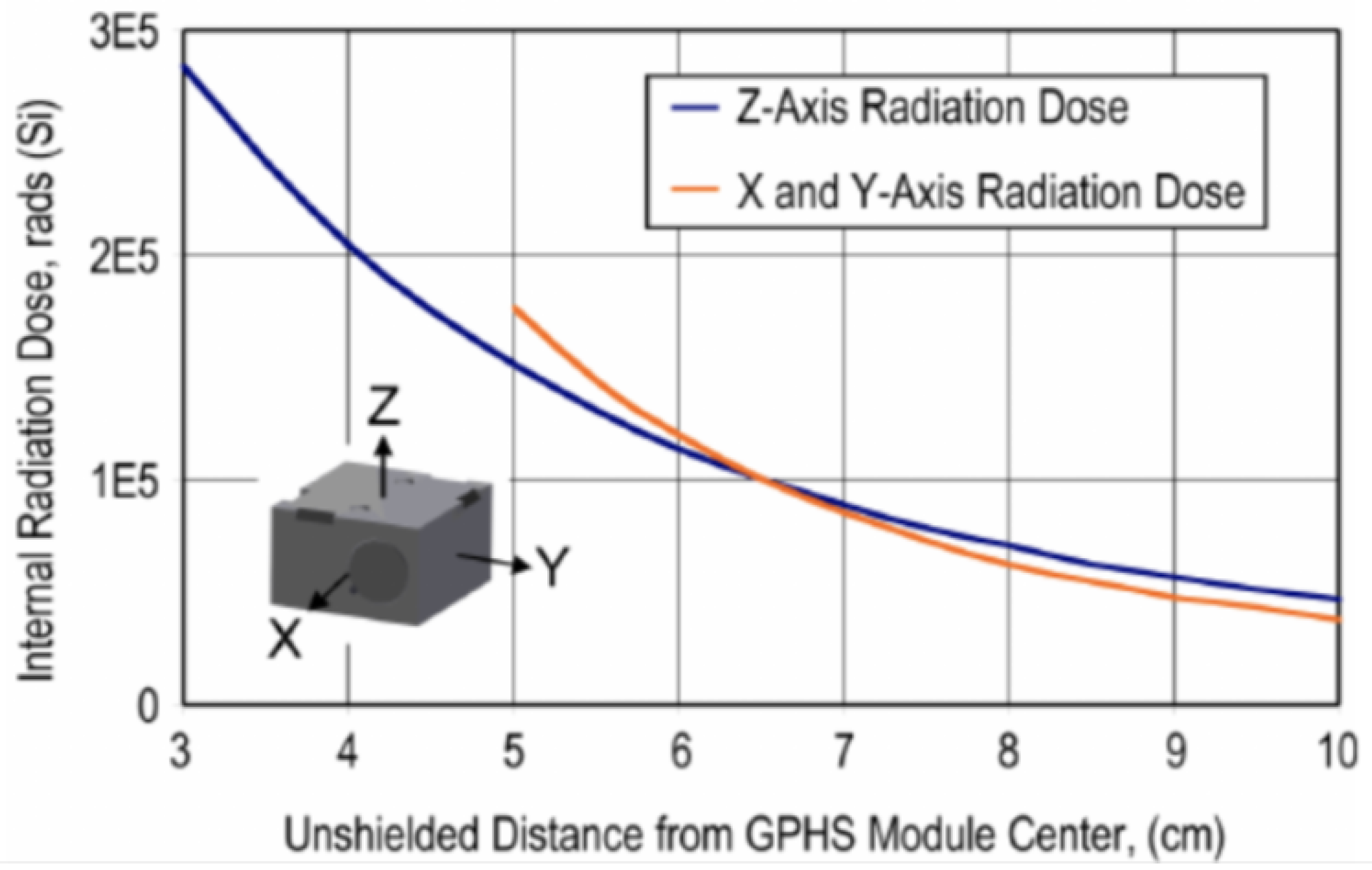

We have shown that a constellation of CubeSats can return valuable data using similar types of instruments as those of larger spacecraft. We also argue that using a constellation of smaller spacecraft presents improvements over the coverage and revisit rates of the planetary surface compared to a traditional spacecraft. Additionally, using a constellation allows the distributed system to collect data that would otherwise be inaccessible or much more difficult to obtain, such as mapping the gravitational field of Uranus or creating a three-dimensional representation of phenomena by observing it from multiple angles using multiple spacecraft. Finally, we have shown that the standard technical budgets (electrical energy, radiation, thermal balance, communications link, data volume, pointing, fuel, mass, and volume) for this mission appear to close with adequate margins, confirming the potential feasibility of the mission architecture.

Moving forward, we plan on gathering more concrete information regarding the instruments that could become the satellite payloads, finalizing the STM, and reaching realistic values on the power, size, data, and pointing constraints of the payloads of each group of CubeSats. We also plan to dive deeper into the mission development process, bringing the concept from a Pre-Phase A level of detail into a more mature Phase A concept, with mission plans and requirements. Potential future directions include studying the constellation dynamics to create navigation plans that include autonomous maneuvers and station keeping.