Abstract

This paper focuses on the issue of unmodeled dynamics and large-range parametric uncertainties in air-breathing hypersonic vehicles (AHV), proposing an adaptive dynamic surface control method based on radial basis function (RBF) neural networks. First, the hypersonic longitudinal model is transformed into a strict-feedback control system with model uncertainties. Then, based on backstepping control theory, adaptive dynamic surface controllers incorporating RBF neural networks are designed separately for the velocity and altitude channels. The proposed controller achieves three key functions: (1) preventing “differential explosion” through low-pass filter design; (2) approximating uncertain model components and unmodeled dynamics using RBF neural networks; (3) enabling real-time adjustment of controller parameters via adaptive methods to accomplish online estimation and compensation of system uncertainties. Finally, stability analysis proves that all closed-loop system signals are semi-globally uniformly bounded (SGUB), with tracking errors converging to an arbitrarily small residual set. The simulation results indicate that the proposed control method reduces steady-state error by approximately 20% compared to traditional controllers.

1. Introduction

Air-breathing hypersonic vehicles (AHV) are characterized by their exceptional speed, rapid response time, and strong penetration capability [1]. As a type of high-tech weapon, AHV plays an important strategic role in national security and benefits. It has now become a research hotspot in the field of aerospace, and the competition is becoming increasingly fierce all over the world [2]. However, the inherent strong nonlinearity and high coupling characteristics of the vehicle, combined with uncertainties and unknown disturbances caused by the flight environment, pose significant challenges to flight control system design. The core technologies of hypersonic vehicles, as a convergence point of aerospace engineering, encompass multiple disciplines and represent a highly integrated system of cutting-edge technologies [3]. The unknown flight environments and variable mission profiles during operation impose dual requirements on vehicle control technology: it must simultaneously ensure maneuverability flexibility while maintaining necessary robustness and adaptability [4]. Consequently, advanced flight control technologies and control system design constitute the fundamental challenge for guaranteeing safe and effective vehicle operation.

The emergence and rapid development of artificial intelligence have led to the widespread application of intelligent control in the field of hypersonic vehicle control. Compared with traditional control methods, intelligent control exhibits unique advantages in addressing control problems of non-modeled systems [5,6]. Therefore, intelligent control has been widely applied to hypersonic vehicles characterized by parameter uncertainties, high nonlinearity, and complex mission requirements [7,8]. The design methodology for vehicle control systems proceeds as follows: First, approximation techniques are employed to estimate unknown functions arising from uncertain influences in the vehicle model. Specifically, the controller utilizes approximated model functions to substitute the unknown functions. Subsequently, based on Lyapunov stability theory, adaptive control laws are constructed to guarantee stability and convergence of the overall control system.

In reference [9], the authors developed a non-singular direct neural network control system. By employing neural networks to estimate both virtual and actual control laws, they achieved stable tracking control of velocity and altitude for hypersonic vehicles under mismatched disturbance conditions. The study in reference [10] utilized neural approximation to construct a nonlinear disturbance observer. This observer effectively estimated unknown disturbances, including coupling effects between flexible and rigid-body states of hypersonic vehicles, resulting in satisfactory tracking performance. In reference [11], the authors addressed the challenge of maintaining stable control for hypersonic vehicles under conditions involving flexible modes, parametric uncertainties, and external disturbances by developing a neural adaptive control strategy. The work presented in reference [12] introduced a novel robust adaptive neural network controller specifically designed to overcome the non-minimum phase characteristics inherent in hypersonic vehicles. Reference [13] proposed a concise fuzzy neural control framework for waverider vehicles with input constraints, which not only guarantees spurred prescribed performance but also avoids the fragility problem associated with existing prescribed performance control (PPC) methods. Reference [14] utilized neural network technology to approximate unknown non-affine dynamics, and combined funnel control with a low-pass filter to propose a control strategy that eliminates the need for virtual control laws. This approach ensures both transient and steady-state performance of the tracking error, though the design is relatively complex and requires numerous parameters. The authors of reference [15] developed a finite-time neural network-based optimal control law for aircraft, which effectively addresses the tracking control problem under angle-of-attack constraints.

The Dynamic Surface Control (DSC) method represents an enhancement of the backstepping approach. Its fundamental principle involves incorporating low-pass filters at each design step of traditional backstepping control, whereby algebraic operations replace differential computations in the design process, thereby effectively circumventing the issue of “differential explosion” [16,17]. Reference [18] designed an adaptive controller based on a Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFNN) to suppress uncertainties and disturbances. In reference [19], the authors developed a novel backstepping control method that eliminates the need for online differentiation of virtual control variables by directly designing control laws for their first-order derivatives using high-order differentiators. Concurrently, a tracking differentiator-based observer was constructed to estimate various uncertain terms in the model. This approach significantly improved the tracking accuracy of the controller, with its effectiveness being rigorously validated through theoretical analysis and numerical simulations. Reference [20] proposed a dynamic surface control method with arbitrarily small tracking error for a class of nonlinear systems with strict-feedback form and unmatched uncertainties. Reference [21] developed an adaptive dynamic surface control method for the velocity and flight path angle of generic hypersonic vehicles, achieving satisfactory control performance. In reference [22], the authors proposed a novel adaptive dynamic surface controller that achieves trajectory tracking control for hypersonic vehicles through neural network approximation.

In addressing the control challenges associated with uncertainties in hypersonic vehicles, the authors of reference [23] developed a fixed-time control law incorporating an adaptive disturbance estimation law and an anti-windup compensator, taking into account factors such as parameter uncertainties and additional disturbances. This approach effectively enhances tracking accuracy. In reference [24], addressing the uncertainty issues in hypersonic vehicles, the authors proposed a composite control strategy incorporating an extreme learning machine-based disturbance observer. Compared with control schemes based on extended state observers, this approach significantly improves the tracking accuracy of both velocity and altitude. In reference [25], addressing the attitude control problem of hypersonic vehicles with stochastic parameter perturbations, the authors designed an error stabilization regulator through a predictive sliding mode control method, which enhanced the system’s robustness against parameter perturbations and nonlinear disturbances. In reference [26], focusing on the flight state during the reentry glide phase of hypersonic vehicles, the authors proposed a fixed-time convergent terminal sliding mode controller to address attitude control challenges involving external disturbances, model uncertainties, and input saturation. In reference [27], the authors developed an output feedback controller based on backstepping control methodology with nonlinear observer compensation, achieving stable tracking control for hypersonic vehicles under both parametric uncertainties and external disturbances.

It should be emphasized that although the aforementioned control strategies demonstrate outstanding tracking performance, their simulation validations were predominantly conducted under conditions where model parameter uncertainties were maintained below 3%. Leveraging the global approximation capability, rapid convergence, simple structure, and online learning capacity of Radial Basis Function (RBF) neural networks, this paper proposes an adaptive dynamic surface control method based on RBF neural networks. The proposed approach aims to address critical challenges in hypersonic vehicle control, including unmodeled dynamics and parametric uncertainties ( and ), with an anticipated 20% reduction in steady-state error. By leveraging the characteristic of RBF neural networks to approximate any continuous nonlinear function on compact sets, this method effectively handles complex unknown nonlinear dynamics in hypersonic vehicles. Compared with multilayer perceptrons, RBF neural networks exhibit faster convergence rates, enabling real-time tracking of system dynamic changes and meeting the stringent real-time requirements of hypersonic flight control. By designing appropriate weight adaptation laws, RBF neural networks can dynamically adjust weight parameters online, enabling real-time compensation for system uncertainties and enhancing the controller’s robustness against parameter variations and external disturbances. The contribution of this paper can be concluded as follows:

- (1)

- Considering the unmodeled dynamics and large-range parametric uncertainties of hypersonic vehicles, a strict-feedback control system with model uncertainties is proposed.

- (2)

- For both velocity and altitude subsystems, adaptive dynamic surface controller design methodologies incorporating RBF neural networks are presented, respectively.

- (3)

- Through stability analysis, while proving that all closed-loop system signals are semi-globally uniformly bounded (SGUB) and the tracking errors converge, design rules for controller parameters are established.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The hypersonic longitudinal model in strict-feedback form with model uncertainties is presented in Section 2. In Section 3, the design methodology for the RBF neural network-based adaptive dynamic surface controller is presented in detail. The nonlinear AHV model simulations and discussions are provided in Section 4, followed by the conclusion in Section 5.

2. AHV Model Description

Based on the longitudinal model of generic air-breathing hypersonic vehicles released by NASA Langley Research Center [28,29,30,31], the nonlinear equations can be formulated as follows:

where , , , and represent the flight velocity, the flight altitude, the flight path angle, the attack angle and the pitch angle rate, respectively. , , represent the throttle setting, the natural frequency, and the damp ratio, respectively. , , represent the gravitational acceleration, the vehicle mass, and the moment of inertia about the y-axis. The lift , the drag , the thrust , and the pitching moment are given as

where , , represent the air density, the reference area and the aerodynamic chord, respectively. The coefficients are modeled by data fitting, the approximations are given as

The hypersonic vehicle model (1) exhibits strong nonlinearity and high coupling characteristics. To facilitate control law design, feedback linearization principles must be applied for linearization treatment. By defining variables and in model (1) as inputs, and velocity and altitude h as outputs, the explicit expressions of the input terms emerge after differentiating and three and four times, respectively, based on the relationship between relative degree and system order, then we can get

where is the state variable of the system. , , , , , .

To validate the controller’s robustness against parameter variations and disturbance rejection capability, this study also considers large-range parametric uncertainties of AHV. The system’s parametric uncertainties primarily stem from time-varying model parameters and aerodynamic coefficients. Specifically, the following uncertain parameters are investigated:

The parametric uncertainties are all bounded quantities, satisfying the following condition: , , , , , ; , , , , , are bounded positive real numbers. When further accounting for unmodeled dynamics , the system state Equation (4) can be more comprehensively described as:

The system output equation is given by:

In the system state Equation (7), , , , , , , represent unknown terms accounting for the system uncertainties, denotes unmodeled dynamics, are functions of the flight state. In the output Equation (8), , .

The control objective is to design an RBF neural network to approximate the model uncertainties and develop an adaptive neural controller that achieves stable tracking control for both velocity and altitude channels. That is ,.

3. Controller Design

3.1. RBF Neural Networks

RBF neural networks can effectively approximate any continuous nonlinear function, where an n-input single-output RBF network with hidden-layer neurons is expressible as . Where is the network’s input vector, denotes the output, represents the adjustable weight vector, is a nonlinear vector function satisfying , and is a Gaussian basis function with the following form:

where , represents the center of the -th Gaussian basis function, while denotes its width parameter.

denotes the approximation error with . Since is unknown, an adaptive law must be designed for online estimation, under the assumption that is bounded with a known positive constant satisfying .

3.2. Design of the Adaptive Neural Network Dynamic Surface Controller

According to the AHV model (7), the velocity channel can be described as the following nonlinear system.

where is the functions of the flight state. , , represent unknown terms accounting for system uncertainties, denote unmodeled dynamics of the velocity channel.

Step 1: Define the first error surface: , we can get

Since is unknown, the first RBF neural network is employed to approximate the function , then have

denotes the ideal weight vector, , represents the approximation error, . By defining , , the virtual control law and RBF adaptive law are designed as follows:

where is a positive real number, is an arbitrarily small positive constant, a nonlinear damping term to counteract the unmodeled dynamics , the estimate of the weight , and a positive real number, .

Step 2: Define the second error surface: , we can get

Since is unknown, the second RBF neural network is employed to approximate the function , then have

denotes the ideal weight vector, , represents the approximation error, . By defining , , the virtual control law and RBF adaptive law are designed as follows:

where is a positive real number, is an arbitrarily small positive constant, a nonlinear damping term to counteract the unmodeled dynamics , the estimate of the weight , and a positive real number, .

Step 3: Define the third error surface: , we can get

Since is unknown, the second RBF neural network is employed to approximate the function , then have

denotes the ideal weight vector, , represents the approximation error, . By defining , , the real control law and RBF adaptive law are designed as follows:

where is a positive real number, is an arbitrarily small positive constant, a nonlinear damping term to counteract the unmodeled dynamics , the estimate of the weight , and a positive real number, .

The variables and in Equations (17) and (20) can be obtained through the following low-pass filter:

Similarly, according to the AHV model (7) altitude subsystem, one has

where is the functions of the flight state. , , , represent unknown terms accounting for system uncertainties, denote unmodeled dynamics.

The virtual control law , the real control law , and the RBF adaptive law are designed as follows:

3.3. Stability Analysis

The stability analysis is primarily conducted in the following three steps.

Step 1: The Lyapunov function is defined and is composed of three parts, respectively: the system state error surfaces , the filtering errors , and the weight estimation errors .

Step 2: The derivative of the Lyapunov function is taken, and the system dynamics, control laws, and adaptation laws are substituted. Cross-terms are handled using Young’s inequality, and the resulting expression is further upper-bounded into the standard form .

Step 3: By selecting appropriate parameters, solving the differential inequality yields . Since is uniformly bounded, it follows from its definition that the tracking error , the filter error , and the weight estimation error are all uniformly bounded. Consequently, the weight estimates are bounded, the virtual control law is bounded, and thus the system states and control input are also bounded.

The filtering error is defined as , , , can be obtained from Equation (21). The weight estimation error is defined as , , , the derivatives of each error surface are:

The derivative of the filtering error is:

According to Equations (17), (20), and (24)–(27), there exists a non-negative continuous function , satisfying:

Then have

The Lyapunov function is defined as follows:

Assumption 1.

The reference trajectory

is bounded, and its first-order and second-order derivatives exist and satisfy , where is a positive real number.

Theorem 1.

Consider the closed-loop system composed of system (11) and the real controller (20). If Assumption 1 holds and the initial conditions satisfy , where is an arbitrary positive constant, then there exist adjustable parameters ,

such that all signals of the closed-loop system are semi-globally uniformly bounded, and the system tracking error can converge to an arbitrarily small residual set.

Proof of Theorem 1.

According to Equation (30), we can get

When the condition A is satisfied, the following compact set may be defined:

Thus, is likewise a compact set. When condition holds, admits its maximum value on the compact set . Moreover, incorporating and invoking (29)–(31), we obtain:

Considering and applying Young’s inequality, we have:

Furthermore, the following can be obtained:

where is the maximum eigenvalue of . The parameters are designed as follows: , , , , , , , , is a positive parameter to be designed. Taking into account , , , we have:

Design parameter such that condition is satisfied. When , we have ; when , then follows. Since constitutes an invariant set, under the premise condition , we obtain , which yields with the solution:

It can be observed that when condition holds (), then under condition (), all error signals in the closed-loop system are semi-globally uniformly bounded (SGUB) within the compact set .

The proof is completed. □

4. Simulation and Discussion

Due to experimental constraints, this study could not conduct hardware-in-loop testing or wind tunnel validation, and the effectiveness of the controller was primarily verified through software simulation.

In this section, numerical simulations are conducted to verify the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed control method. The mathematical model of the AHV is built on the MATLAB (2019)/Simulink platform, and the designed controller is also simulated and verified with MATLAB (2019).

Numerical simulations are performed based on the air-breathing hypersonic vehicle model (1), with initial conditions as shown in Table 1. The control input constraints used in the AHV are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Initial flight condition and uncertainty boundary.

Table 2.

Control input constraints of the AHV.

The reference trajectories for velocity and altitude are set as step signals of 50 m/s and 50 m, respectively, and are generated through the following filter:

Based on the method proposed in this paper, RBF neural network structures are employed to approximate the unknown terms , , in the velocity channel and the unknown terms , , , in the altitude channel, respectively. The configurations of the RBF networks selected for approximation are shown in Table 3. The tuning guidelines of some controller parameters are provided in Table 4.

Table 3.

RBF Network Structure.

Table 4.

The tuning guidelines of some controller parameters.

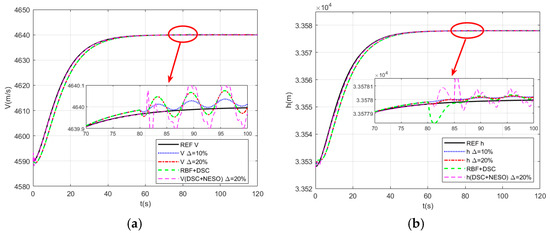

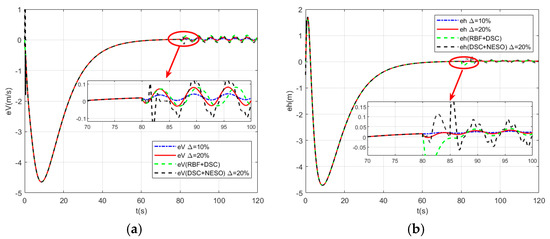

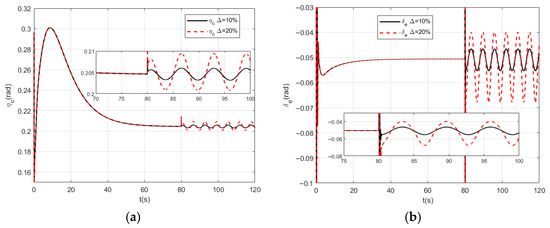

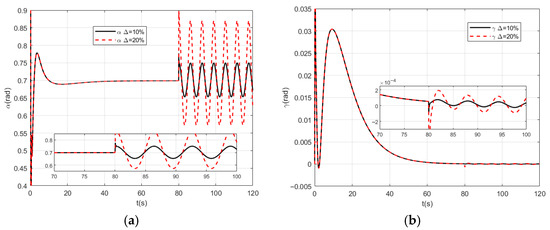

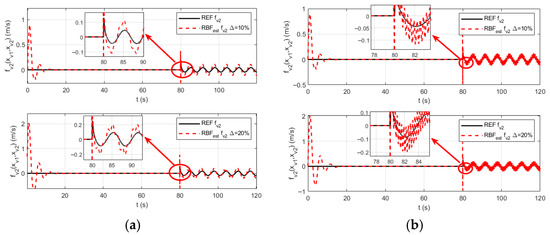

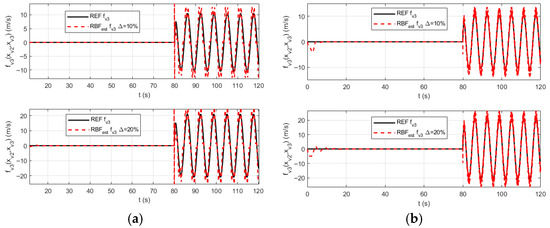

To better validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, parameter uncertainties of and were introduced at t = 80 (s), respectively. The simulation results are shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Figure 1.

(a) Responses of the velocity; (b) Responses of the altitude.

Figure 2.

(a) Responses of the velocity error; (b) Responses of the altitude error.

Figure 3.

(a) Responses of the throttle setting; (b) Responses of the elevator deflection.

Figure 4.

(a) Responses of the attack angle; (b) Responses of the flight path angle.

Figure 5.

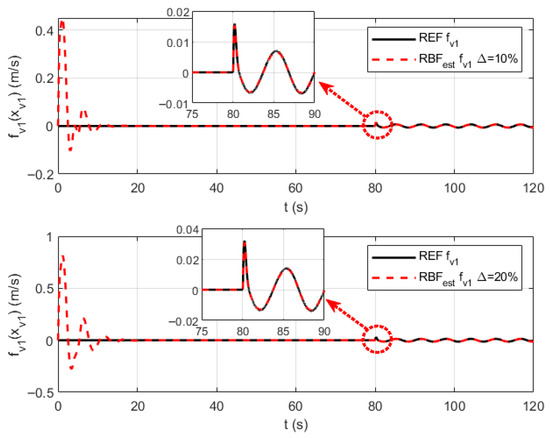

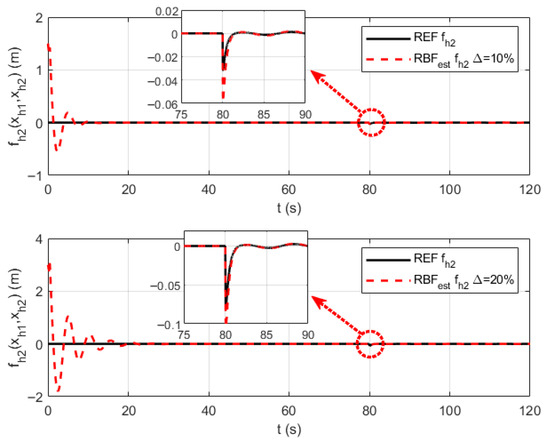

The RBF neural network approximation curves for parameter uncertainties .

Figure 6.

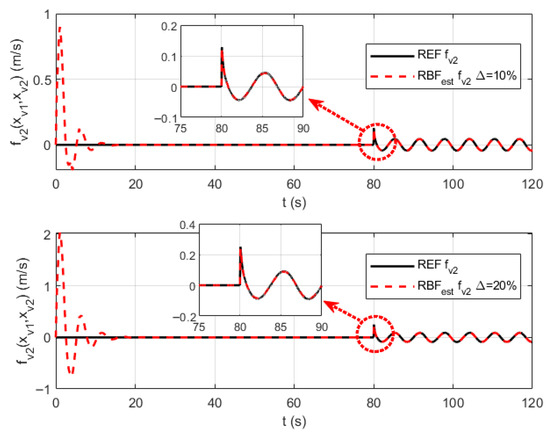

The RBF neural network approximation curves for parameter uncertainties .

Figure 7.

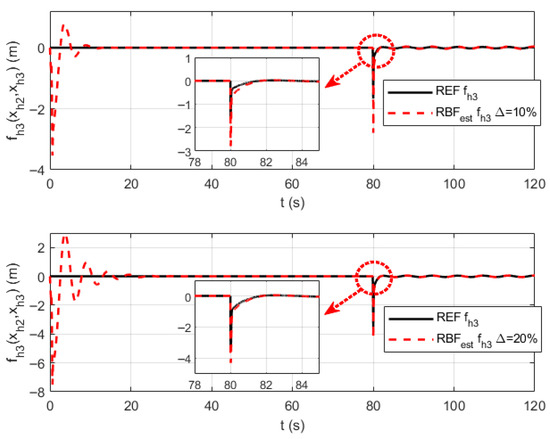

The RBF neural network approximation curves for parameter uncertainties .

Figure 8.

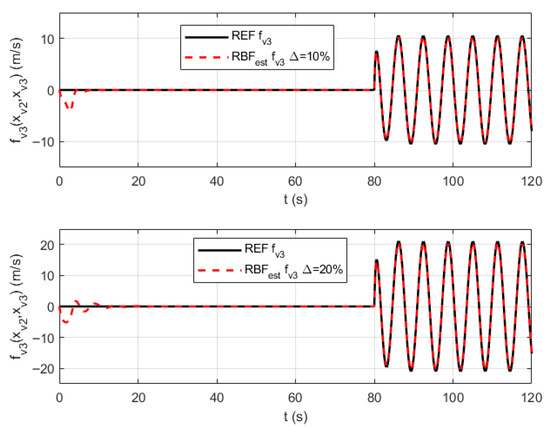

The RBF neural network approximation curves for parameter uncertainties .

Figure 9.

The RBF neural network approximation curves for parameter uncertainties .

Figure 10.

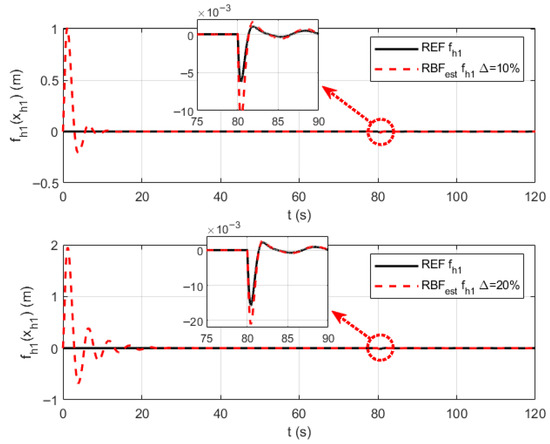

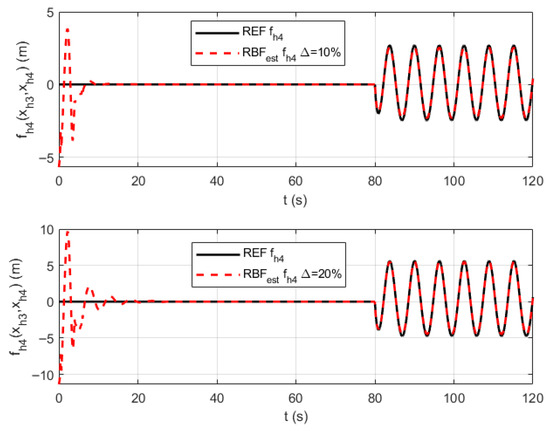

The RBF neural network approximation curves for parameter uncertainties .

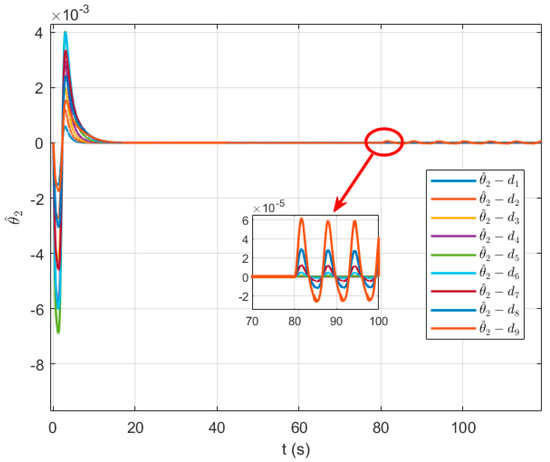

Figure 11.

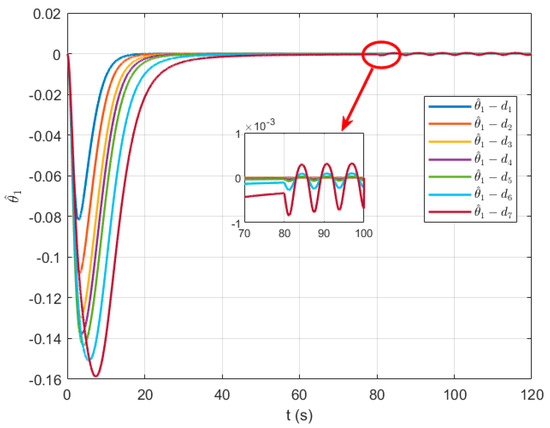

The RBF neural network approximation curves for parameter uncertainties .

Figure 12.

Variation curve of the RBF adaptive parameter .

Figure 13.

Variation curve of the RBF adaptive parameter .

Figure 14.

Variation curve of the RBF adaptive parameter .

Figure 1 shows the response curves of velocity and altitude, and it can be seen from the curves that the proposed control method achieves stable tracking control of the aircraft’s velocity and altitude. The entire response curve is smooth and free of overshoot, with only minor oscillations occurring after the introduction of parameter uncertainties. The oscillation amplitude for is slightly larger than that for . Figure 2 displays the velocity error response curve and the altitude error response curve. As observed in the figure, under a 10% parameter perturbation, the velocity tracking error remains below 0.05, while the altitude tracking error stays under 0.02. When the parameter perturbation increases to 20%, the velocity tracking error is less than 0.08, and the altitude tracking error does not exceed 0.05. In contrast, the traditional DSC control method exhibits a velocity tracking error of approximately 0.1 and an altitude tracking error of about 0.06. Table 5 provides a performance comparison of different control schemes. From the table, it can be seen that under parameter perturbation, the root mean square errors for velocity and altitude of the traditional DSC control method are 0.089 and 0.052, respectively. The control method (RBF+DSC) proposed in Reference [22] shows significant improvement in steady-state performance, with root mean square errors for velocity and altitude of 0.078 and 0.044, respectively. Compared to Reference [22], the control scheme proposed in this paper still achieves a slight improvement, with root mean square errors for velocity and altitude of 0.074 and 0.038, respectively. Experimental results demonstrate that, compared to traditional control methods, the proposed method significantly enhances the tracking accuracy of the system under parameter perturbations, with a steady-state accuracy improvement of approximately 20%. When compared to Reference [22], the performance improvement is about 5%. Figure 3 shows the response curves of the control signals for throttle setting and elevator deflection angle. Throughout the entire control process, the curves remain smooth without high-frequency oscillations. Figure 4 shows the response curves of the angle of attack and flight path angle.

Table 5.

Performance Comparison of Different Control Schemes.

Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 respectively present the RBF neural network approximation curves for parameter uncertainties , , and in the velocity channel. Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively, present the RBF neural network approximation curves for parameter uncertaintie , , , and in the altitude channel. As can be seen from the approximation curves, the proposed control method achieves rapid convergence to unknown parameters under both 10% and 20% parameter uncertainties, with smooth approximation curves and minimal error throughout the process. From an overall perspective, the RBF approximation curves successfully capture the main changing trends of the reference curves, with no instances of runaway or divergence, verifying their stability. Under model parameter perturbations of and , the approximation error does not significantly worsen, demonstrating that the designed RBF network has a good adaptability to variations in data. More notably, in Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, when the unknown functions are bivariate functions, the RBF network successfully learns such complex coupling relationships, enabling the approximation curves to closely track the reference curves. This indicates the effectiveness of the RBF network in handling multi-input nonlinear mapping problems.

Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 present the variation curves of the adaptive laws in the velocity channel. Overall, all adaptive parameters eventually converge to stable constant values, demonstrating the controller’s capability to online adjust parameters in response to system dynamics and uncertainties while maintaining closed-loop system stability. The adaptive parameters , , and exhibit high-frequency oscillations only during the initial stage (approximately 0–20 s), after which they rapidly converge to steady-state values. When a parameter perturbation is introduced at 80 s, the adaptive parameters promptly readjust, showing high-frequency, low-amplitude oscillations and converging to a bounded region of minor fluctuations. This behavior enables the controller to effectively approximate unknown functions and unmodeled dynamics.

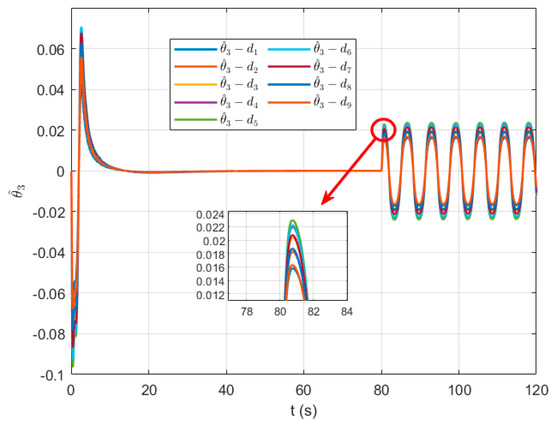

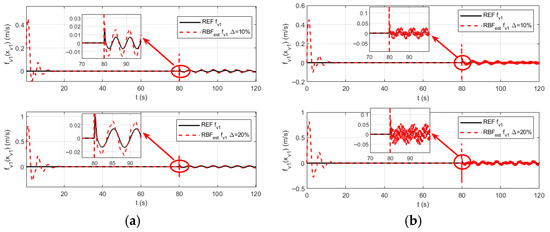

Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17 present the approximation curves of the RBF neural network under parameter perturbation conditions, where subplot (a) represents a 30% reduction in Gaussian width with a 30% increase in center points, and subplot (b) represents a 30% increase in Gaussian width with a 30% reduction in center points. The figures demonstrate that when the Gaussian width decreases and the center points increase, the network’s approximation capability becomes insufficient, leading to increased approximation errors and curve distortion. Conversely, when the Gaussian width increases and the center points decrease, it equates to using numerous wide basis functions for curve fitting, resulting in an over-parameterized system that is highly sensitive to noise and numerical errors, ultimately causing output instability and oscillations. Further simulation studies reveal that simultaneous increases or decreases in Gaussian width and center points within a small range result in negligible changes to the approximation curves. Therefore, in the design of RBF networks, it is essential to ensure moderate and smooth overlapping between neurons to achieve accurate approximation without blind spots while avoiding oscillations.

Figure 15.

The approximation curve of by the RBF neural network under parameter perturbations: (a) The Gaussian width is decreased by 30%, and the center points are increased by 30%; (b) The Gaussian width is increased by 30%, and the center points are decreased by 30%.

Figure 16.

The approximation curve of by the RBF neural network under parameter perturbations: (a) The Gaussian width is decreased by 30%, and the center points are increased by 30%; (b) The Gaussian width is increased by 30%, and the center points are decreased by 30%.

Figure 17.

The approximation curve of by the RBF neural network under parameter perturbations: (a) The Gaussian width is decreased by 30%, and the center points are increased by 30%; (b) The Gaussian width is increased by 30%, and the center points are decreased by 30%.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses control challenges such as unmodeled dynamics and wide-range parameter uncertainties in air-breathing hypersonic vehicles by proposing an adaptive dynamic surface control method based on RBF neural networks. Targeting the longitudinal model of an uncertain hypersonic vehicle, the system is transformed into a strict-feedback control system with model uncertainties. The RBF neural network is employed to approximate the unmodeled dynamics, while the dynamic surface control technique prevents differential explosion. The simulation results verify that the RBF-based approximation scheme can accurately capture the dominant dynamics of all functions to be estimated and exhibits strong robustness against model uncertainties. This approach significantly improves the system’s tracking accuracy under parameter perturbations, achieves the expected performance, and confirms the effectiveness of the proposed method. In summary, the RBF neural network-based adaptive dynamic surface control method proposed in this paper is effective and successful.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.L. and L.D.; methodology, O.L.; software, O.L. and L.D.; validation, O.L. and L.D.; formal analysis, O.L.; investigation, L.D.; resources, L.D.; data curation, O.L.; writing—original draft preparation, O.L.; writing—review and editing, L.D.; visualization, O.L.; supervision, L.D.; project administration, O.L. and L.D.; funding acquisition, O.L. and L.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62461017, in part by the Science and Technology Project of Huzhou City under Grant 2025GY010, and in part by the Doctoral Foundation of Chengdu Technological University under Grant 2024RC043.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the colleagues for their assistance throughout this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Lu, K. Research progress and prospect of the hypersonic flight vehicle control technology. J. Astronaut. 2022, 43, 866–879. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C. Development status, challenges and trends of strength technology for hypersonic vehicles. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2022, 43, 527590. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Xia, H. A Learning-based Intelligent Control Method for Hypersonic Flight Vehicle. J. Astronaut. 2023, 44, 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Li, S.; Sun, C.; Guo, L. Nonlinear Disturbance Observer Based Robust Flight Control for Airbreathing Hypersonic Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2013, 49, 1263–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Qi, Q. Fuzzy optimal tracking control of hypersonic flight vehicles via single-network adaptive critic design. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 30, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Qi, Q.; Jiang, B. A Simplified Finite-time Fuzzy Neural Controller with Prescribed Performance Applied to Waverider Aircraft. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 30, 2529–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, Q. Fuzzy Adaptive Non-Affine Attitude Tracking Control for a Generic Hypersonic Flight Vehicle. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yi, J.; Pu, Z. Adaptive fuzzy Nonsmooth Backstepping Output Feedback Control for Hypersonic Vehicles with Finite Time Convergence. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 28, 2320–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Wu, X.; Zhen, M. Nonsingular Direct Neural Control of Air-breathing Hypersonic Vehicle via Back-Stepping. Neurocomputing 2015, 153, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. DOB-Based Neural Control of Flexible Hypersonic Flight Vehicle Considering Wind Effects. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 8676–8685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Shao, X. Neural Adaptive Appointed-time Control for Flexible Air-breathing Hypersonic Vehicles: An Event Triggered Case. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 9545–9563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Shi, Z. Robust Adaptive Neural Control of Nonminimum Phase Hypersonic Vehicle Model. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 51, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Jiang, B.; Lei, H. Low-Complexity Fuzzy Neural Control of Constrained Waverider Vehicles via Fragility-Free Prescribed Performance Approach. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 2127–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X. Air-breathing hypersonic vehicles funnel control using neural approximation of non-affine dynamics. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2018, 23, 2099–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, L. Finite-Time Neural Optimal Control for Hypersonic Vehicle With AOA Constraint. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 867–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yang, C.; Pan, Y. Global Neural Dynamic Surface Tracking Control of Strict-Feedback Systems With Application to Hypersonic Flight Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 26, 2563–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yang, H.; Sun, J.; Xu, S. Adaptive neural dynamic surface control for nonstrict feedback systems with state delays. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2024, 34, 9515–9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Guo, Z.; Wang, G.; Wang, C. Neural adaptive control of air-breathing hypersonic vehicles robust to actuator dynamics. ISA Trans. 2021, 116, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Jia, Z.; Liu, X.; Lu, K. Backstepping Control for Hypersonic Vehicles without Online Differentiation. J. Astronaut. 2022, 43, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Swaroop, D.; Hedrick, J.; Yip, P. Dynamic Surface Control for a Class of Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2002, 45, 1893–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, W.; Yan, L.; Kendrick, A. Adaptive Dynamic Surface Control of a Hypersonic Flight Vehicle with Improved Tracking. Asian J. Control 2013, 15, 594–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J. Adaptive Dynamic Surface Control for a Hypersonic Aircraft Using Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2017, 55, 2277–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Gu, X.; Li, L. Fixed-time Anti-saturation Control for Hypersonic Morphing Flight Vehicle. J. Astronaut. 2025, 46, 731–740. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Chen, Z.; Cai, Y.; Tang, W. Disturbance Compensation and Decoupling Optimal Backstepping Control Strategy for Hypersonic Vehicle. J. Xi’An Jiaotong Univ. 2025, 59, 170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, R. Attitude control of hypersonic vehicle with random parameter perturbations. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2024, 46, 703–714. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; E, B.; Wang, X.; Cui, N. A Fixed-time Sliding-mode Control Method for Hypersonic Vehicle. J. Astronaut. 2024, 45, 560–570. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, J.; Sharma, M.; Polycarpou, M. Backstepping-Based Flight Control with Adaptive Function Approximation. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2005, 28, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolender, M.; Doman, D. Nonlinear longitudinal dynamical model of an air-breathing hypersonic vehicle. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2007, 44, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Baris, F.; Jang, J.; Mohamed, K. Adaptive mode switching of hypersonic morphing aircraft based on type-2 TSK fuzzy sliding mode control. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2015, 58, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, C. Approximate Back-Stepping Fault-tolerant Control of the Flexible Airbreathing Hypersonic Vehicle. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2016, 21, 1680–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhen, Z. Adaptive backstepping control for air-breathing hypersonic vehicle subject to mismatched uncertainties. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 107, 106244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).