Although the hose–drogue aerial refueling system has been widely adopted for its structural simplicity and operational flexibility, the drogue remains highly susceptible to disturbances such as tanker wake turbulence, receiver bow-wave effects, and atmospheric gusts. Such disturbances often result in unstable drogue motion, increased probe–drogue misalignment, and reduced refueling success rates. To address these challenges, active stabilization of the drogue has been proposed as a promising solution. By integrating actuation mechanisms and control strategies into the drogue design, the system can enhance positional stability and improve docking reliability.

3.1. Structural Design of the Active Stabilization Drogue

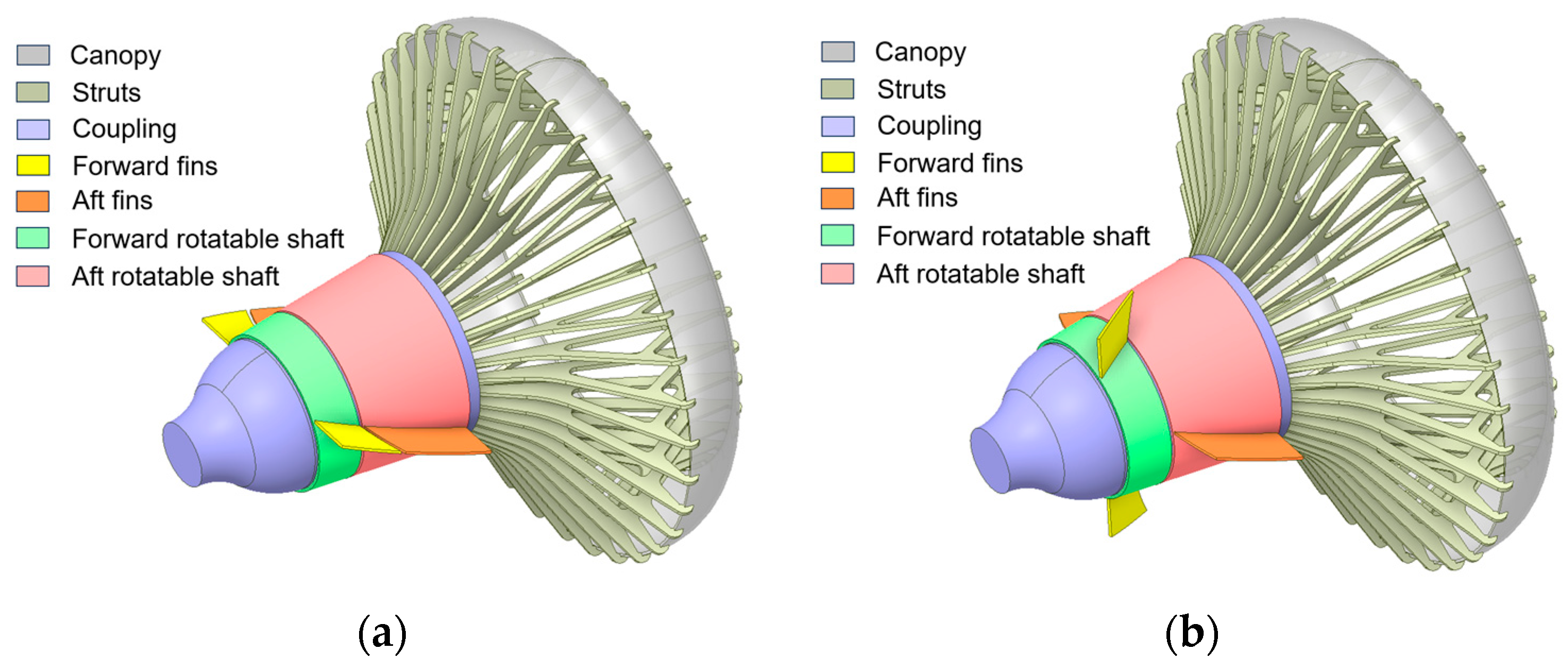

To enhance the aerodynamic stability of the drogue, two pairs of strake-type control fins are mounted on the outer surface of the conventional drogue shell, as shown in

Figure 9. Each side consists of a single flat plate aligned along the shell and then axially split into a forward and an aft segment. These two segments are installed on independent coaxial rotating shafts, enabling differential deflection between the forward and aft fins and thereby generating controllable aerodynamic forces. The arrangement on the opposite side is a mirror image to maintain geometric and aerodynamic symmetry. It is assumed that the total mass of the drogue remains constant after the inclusion of the strake-fins, as their added weight is negligible compared with the overall drogue mass.

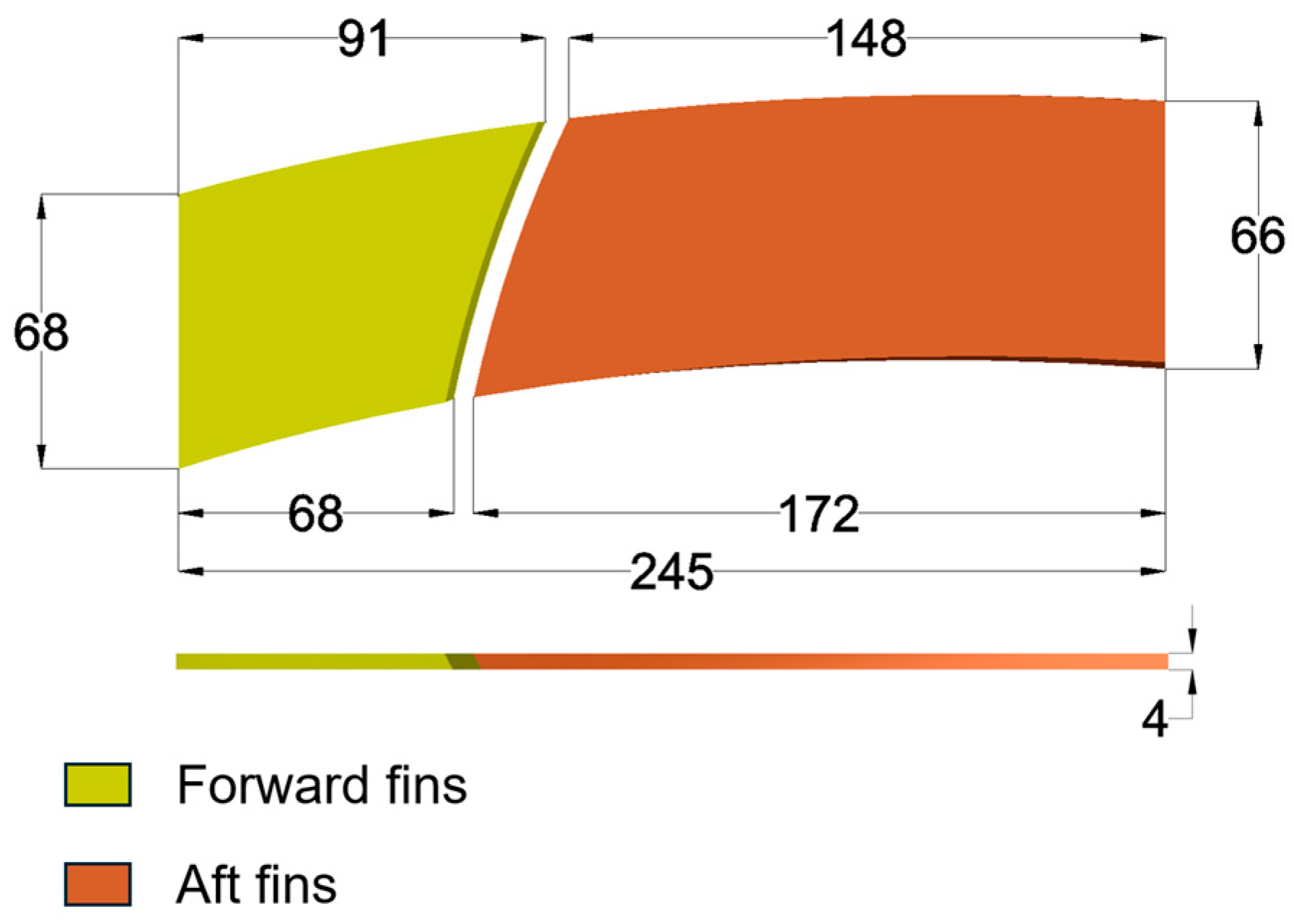

The term “strake-type” refers to slender, low-aspect-ratio aerodynamic surfaces aligned with the drogue shell. The fins adopt a rectangular–tapered planform, with their size determined by the available axial length of the drogue shell. To maximize control authority, the fins span nearly the full usable axial length of the drogue while remaining compatible with refueling pod retraction. The geometric configuration of the single-side strake-fin assembly is illustrated in

Figure 10. Each single-side strake-fin assembly has a total axial length of 245 mm and a thickness of 4 mm. The forward fin has a root chord length of 68 mm and a span of 68 mm, while the aft fin has a root chord length of 172 mm and a span of 66 mm. These dimensions were obtained through CFD-based parametric studies to balance aerodynamic performance, flow quality, and structural integration.

The strake-type control fins generate lift, drag, and side forces, as well as the corresponding pitching and yawing moments acting on the drogue. By adjusting the deflection angles of the forward and aft fins, the magnitude and direction of these aerodynamic forces and moments can be effectively controlled, providing sufficient control authority to stabilize the drogue against various external disturbances. Importantly, the use of two axially distributed fin pairs rather than a single larger pair allows for greater control flexibility and finer aerodynamic modulation. By tuning the relative deflections of the forward and aft fins, the system can adjust not only the total magnitude of forces and moments but also their distribution along the drogue axis. This enhances the ability to regulate attitude precisely and improves the disturbance rejection capability under complex aerodynamic environments.

The functional principle is as follows:

1. Aft fins, located near the canopy rim, provide a longer effective moment arm and thus offer stronger control authority and faster dynamic response.

2. Forward fins, positioned near the mid-cone region, provide fine-tuning capability and enhance stability.

3. By adjusting the relative deflection angles of the forward and aft fins, the system can generate the required aerodynamic forces and moments to actively stabilize the drogue and suppress its oscillatory motion under disturbed flight conditions.

In addition to its active control capability, the strake-fin layout also enhances the drogue’s passive aerodynamic stability in quiescent flow by increasing restoring moments through its distributed fin arrangement.

3.2. Aerodynamic Data Analysis

CFD simulations were performed to establish an aerodynamic database for the drogue. An unstructured computational mesh containing approximately 2.1 million cells was employed. Local mesh refinement was applied around both the drogue surface and the strake-fin control surfaces to accurately resolve boundary-layer development, fin-induced vortical structures, and wake flow characteristics. Pressure far-field boundary conditions were imposed at the outer domain boundaries, and no-slip wall conditions were applied to all solid surfaces.

The resulting aerodynamic coefficients were organized into a multi-dimensional lookup table parameterized by angle of attack (), sideslip angle (), and the relative deflection angle between the forward and aft fins (). For each input triplet (), the lookup table returns the corresponding aerodynamic forces and moments of the drogue and fins for use in the dynamic simulation.

Because the drogue is specifically designed to operate within a defined flight speed range, its effective aerodynamic angles remain small under steady-state conditions. Therefore, the CFD sampling was limited to the range (). Within this range, aerodynamic quantities during the simulation were obtained using trilinear interpolation between tabulated data points. For queries slightly outside the tabulated bounds, linear extrapolation was applied to ensure continuity while minimizing computational cost.

This small-angle assumption significantly reduces the computational effort required for database construction while remaining valid within the drogue’s operational envelope. The resulting database provides a high-fidelity and computationally efficient description of the drogue aerodynamics, enabling accurate force and moment prediction during dynamic simulations.

Figure 11 summarizes the dependence of lift on

,

, and

. In

Figure 11a, lift acting on the drogue body itself increases nearly linearly with

in the range

, whereas its sensitivity to

is weak, indicating that

is the dominant factor.

Figure 11b plots the lift coefficient generated by the strake-type fins as a function of

for the four boundary cases. The curves exhibit a pronounced minimum near

and maxima near

and

, with approximate symmetry about

. Increasing

primarily shifts the entire curve upward, while varying

produces only minor changes.

Figure 12 summarizes the dependence of drag on

,

, and

. As shown in

Figure 12a, drag decreases gradually with increasing

and

; however, the overall reduction is less than 1%, indicating a relatively minor influence.

Figure 12b plots the drag coefficient versus

for the four boundary cases. The drag coefficient exhibits a periodic trend, first decreasing, then increasing, and finally decreasing again, with approximate symmetry about

.

Figure 11b and

Figure 12b illustrate the lift and drag coefficients of the strake-type fins as functions of the relative fin deflection angle (

), which is defined as the angular difference between the forward and aft strake fins. The coefficients are nondimensionalized using the drogue reference area (

) and the dynamic pressure (

). These figures explicitly show how the aerodynamic coefficients vary with the fin deflection angle, providing a clear representation of the lift and drag trends required for the control system design. Both (

) and (

) show near-symmetry about

, which reflects the geometric symmetry of the fin configuration. Increasing the angle of attack primarily shifts the entire

–

and

–

curves upward, while the sideslip angle introduces only minor deviations.

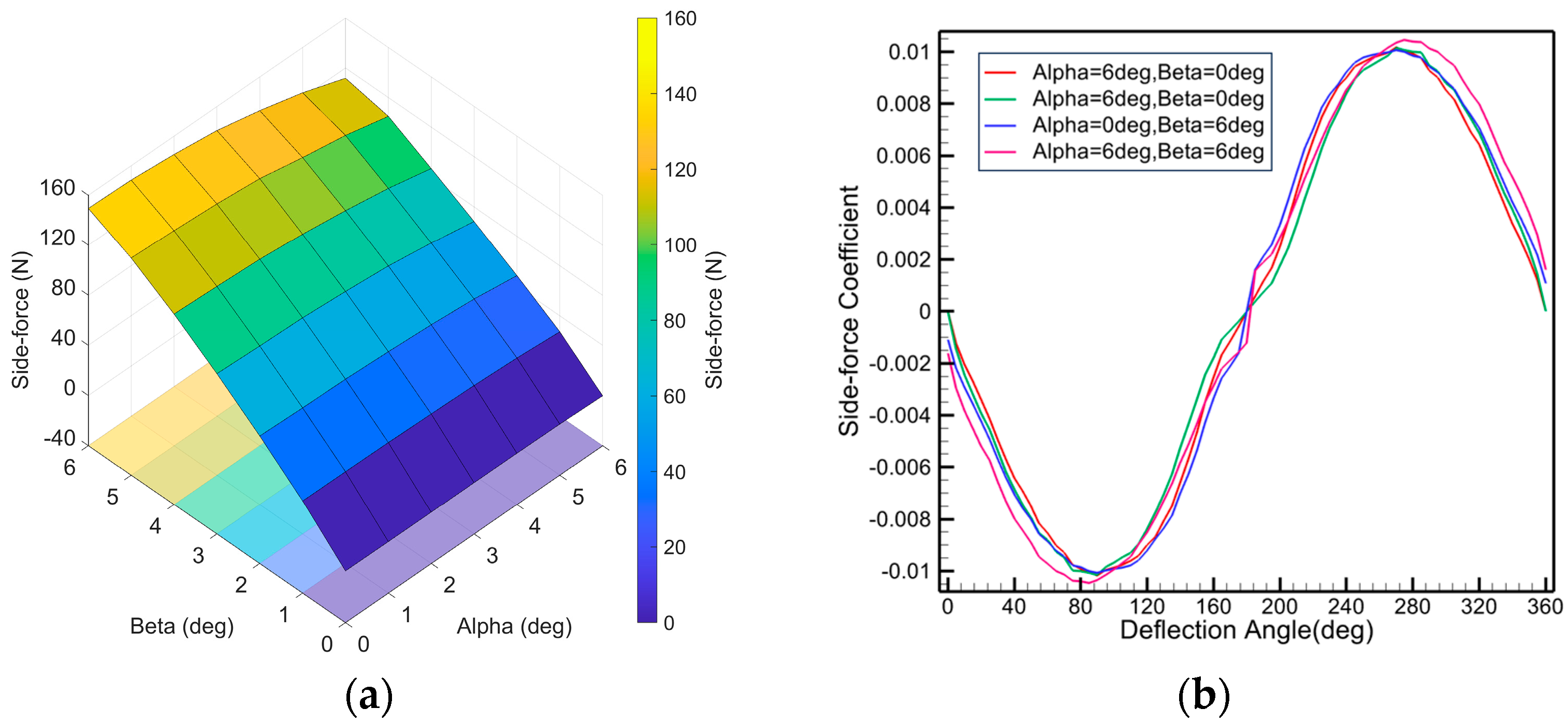

Figure 13 summarizes the dependence of side force on

,

, and

. In

Figure 13a, side force increases nearly linearly with

in the range

, whereas its sensitivity to

is weak, indicating that

is the dominant factor.

Figure 13b shows that the lateral force coefficient varies approximately in a sinusoidal manner with the deflection angle from

to

, reaching a negative peak near

, returning to zero around

, attaining a positive peak near

, and again approaching zero near

. This periodic trend highlights the geometric symmetry of the strake-fin configuration.

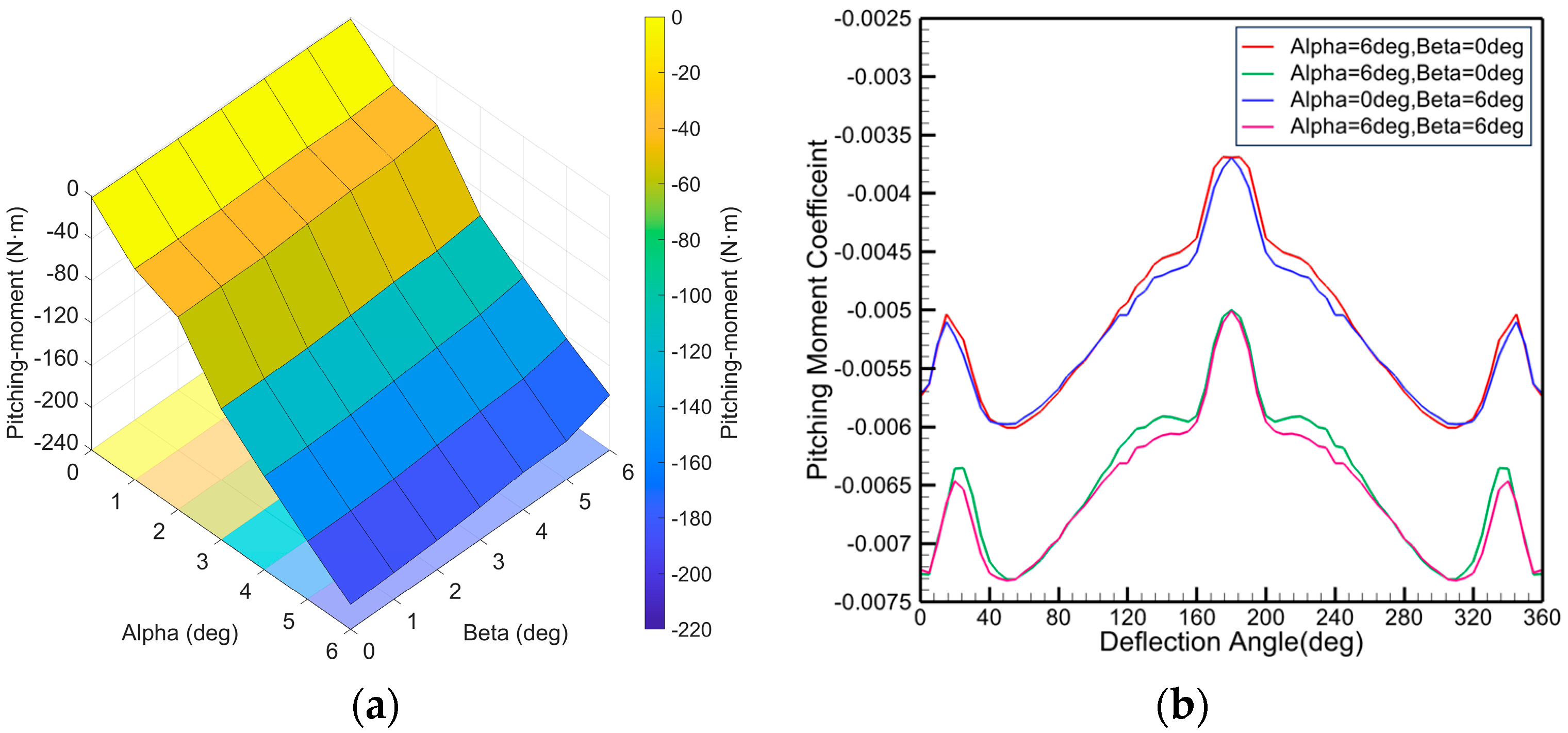

Figure 14 summarizes the dependence of pitching moment on

,

, and

. In

Figure 14a, pitching moment increases nearly linearly with

in the range

, whereas its sensitivity to

is weak, confirming that

is the dominant factor.

Figure 14b plots the pitching-moment coefficient versus

for the four boundary cases. The curves exhibit a periodic distribution: a pronounced maximum occurs near

, while local peaks appear near

and

. The variation is approximately symmetric about

. Increasing

shifts the curves downward, thereby strengthening the nose-down moment, while the effect of

remains minor, producing only small amplitude changes.

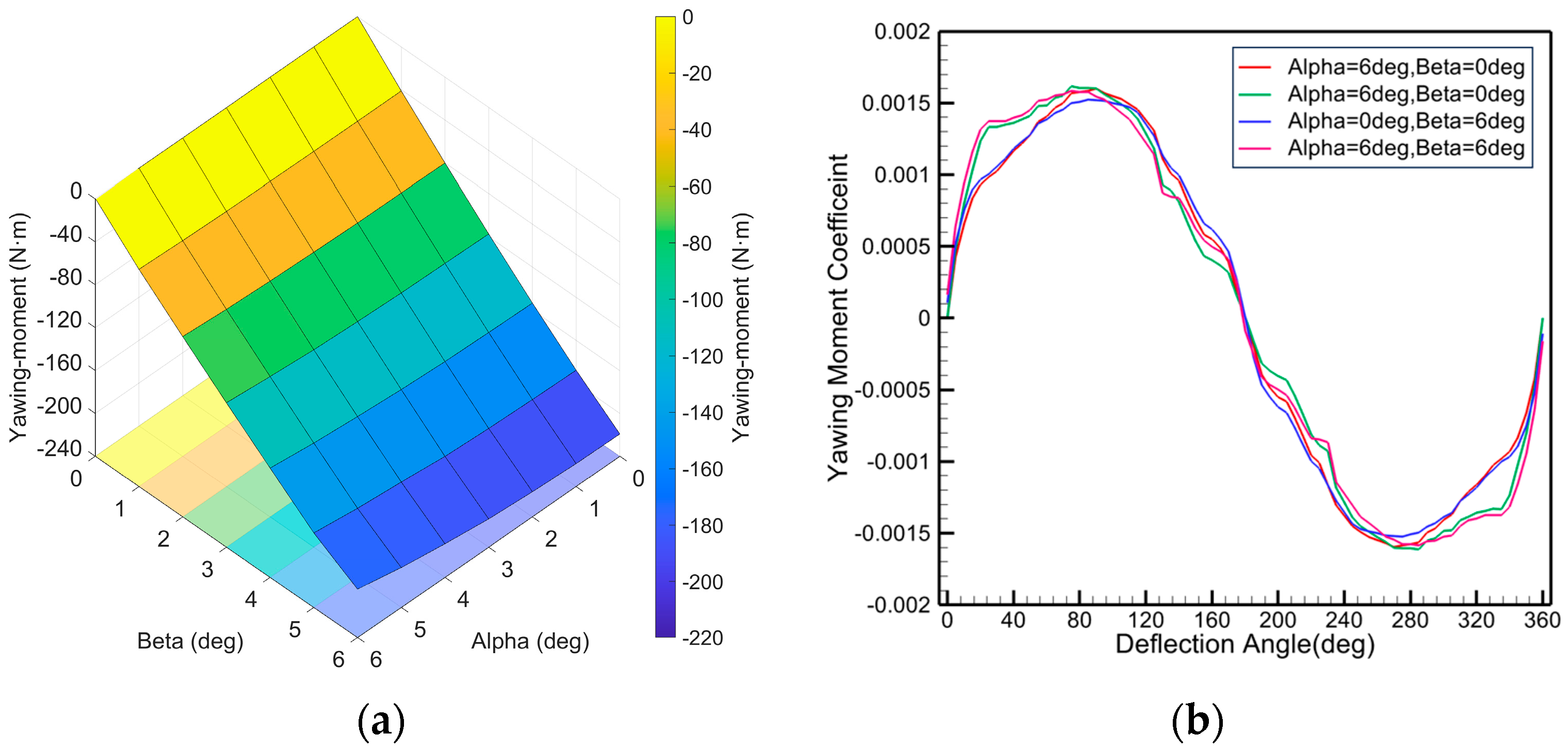

Figure 15 summarizes the dependence of yawing moment on

,

, and

. In

Figure 15a, yawing moment increases nearly linearly with

in the range

, whereas its sensitivity to

is weak, indicating that

is the dominant factor.

Figure 15b shows that the yawing moment coefficient varies approximately in a sinusoidal manner with the deflection angle from

to

, reaching a positive peak near

, returning to zero around

, attaining a negative peak near

, and again approaching zero near

.

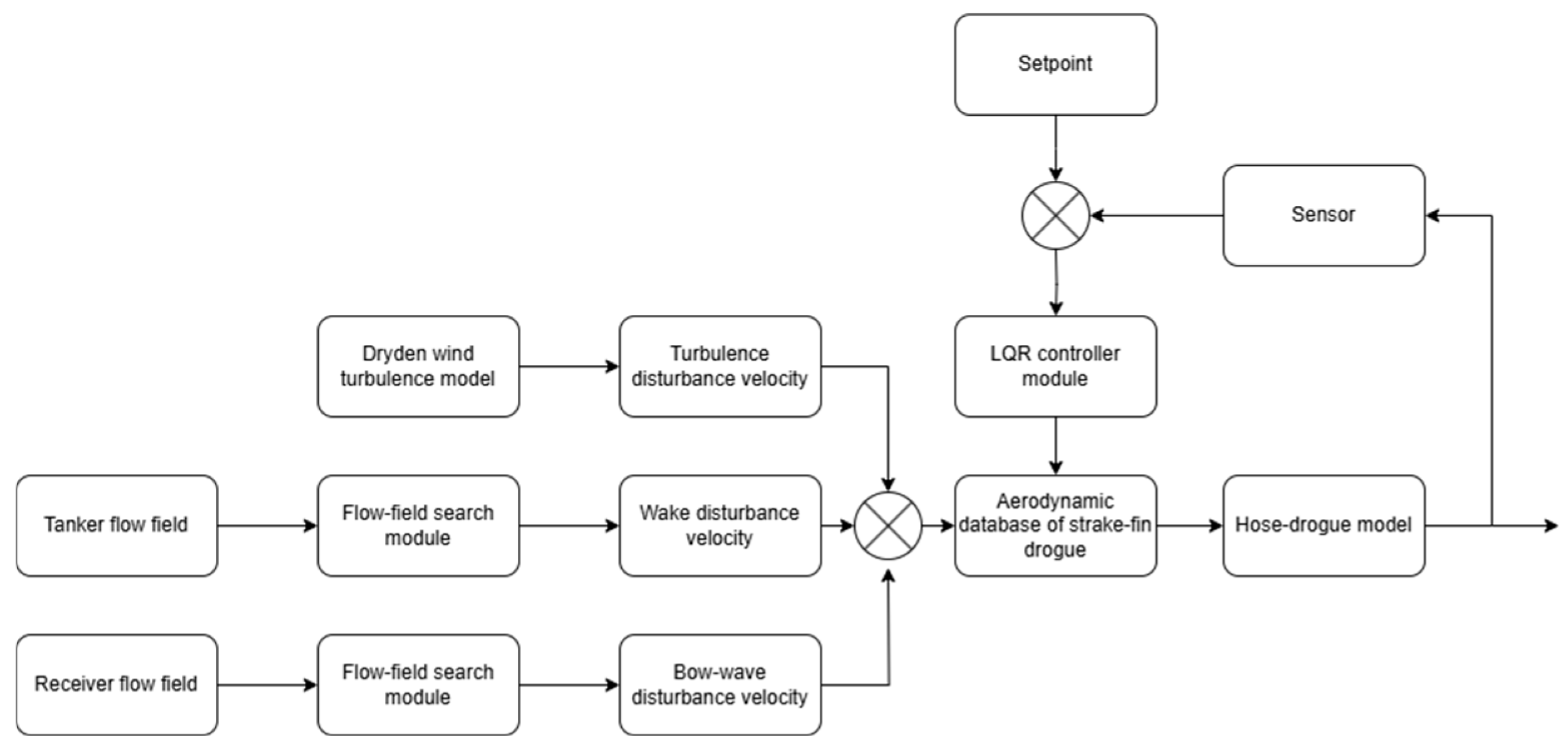

3.4. Design of LQR Control System

An LQR-based control strategy is employed to actively regulate the aerodynamic forces acting on the stabilized drogue by adjusting the deflection angles of the forward and aft strake fins through servo actuators. The objective of the controller is to minimize the drogue’s position and attitude deviations caused by external disturbances—such as tanker wake, receiver bow wave, and atmospheric turbulence—thereby maintaining stable relative positioning between the drogue and the receiver probe.

The Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) is selected because it provides an optimal state-feedback control law that minimizes a quadratic cost function balancing system deviation and control effort. In real time, the drogue’s position, velocity, attitude, and angular rate are continuously fed back into the controller. Based on this state information, the LQR controller computes the optimal fin deflections required to counteract disturbance-induced motion. These commands are then transmitted to the fin actuators, which adjust the forward and aft fins’ deflection angles to generate corrective aerodynamic forces and moments. This closed-loop control mechanism ensures rapid disturbance rejection, suppresses drogue oscillations, and maintains the drogue within the required operational envelope for successful aerial refueling.

Compared with conventional PID control, which requires manual gain tuning and offers limited stability guarantees in coupled multivariable systems, the LQR formulation ensures global stability and smooth control allocation through the algebraic Riccati solution. Although Model Predictive Control (MPC) could handle constraints explicitly, its computational cost limits real-time applicability. The LQR approach therefore represents an effective balance between theoretical optimality, numerical efficiency, and practical implementation feasibility for active drogue stabilization.

The simulation workflow of the LQR control system is illustrated in

Figure 16. The model integrates aerodynamic and disturbance modules, including the tanker wake, receiver bow-wave, and atmospheric turbulence, with the LQR controller and drogue actuator dynamics.

The feedback signals required by the LQR controller include the drogue’s position, attitude, and angular rate. These quantities are assumed to be measured by an onboard Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) and a Differential GPS (DGPS) system or a vision-based photogrammetric method. The IMU provides angular velocity and attitude information, while DGPS or optical tracking supplies the drogue’s relative position with respect to the tanker. For control design and simulation purposes, the sensor data are modeled as ideal (noise-free and delay-free) measurements, enabling assessment of the controller’s intrinsic performance.

The state vector in the LQR controller is defined as the deviation of the drogue’s motion variables from their equilibrium values,

Here, and represent lateral and vertical positions, , denote velocity components, , are aerodynamic angles, and , are angular rates. The overbarred quantities denote the desired target values corresponding to the commanded drogue position and attitude. The control input vector is defined as , where and are the forward and aft fin deflections.

The weighting matrices in the LQR controller are designed as follows:

Here, the first block in Q corresponds to the drogue’s lateral and vertical position errors, which dominate the control objective. The remaining blocks represent the velocities, angles of attack and sideslip, and angular velocities, which receive significantly smaller weights. The relatively large ratio between Q and R ensures precise position tracking while limiting fin deflection amplitude and maintaining smooth actuator dynamics.

The LQR controller operates at an update rate of 100 Hz (). This update frequency enables real-time correction of drogue motion under aerodynamic disturbances.

The forward and aft strake fins are actuated by independent rotary motors that allow continuous 360° rotation about the drogue surface; thus, no mechanical angle saturation is applied. The LQR controller outputs the desired relative deflection angle () between the two fin pairs, which can vary freely within 0–360°. To ensure smooth and realistic actuation, a symmetric rate limiter is introduced, constraining the maximum angular velocity to . This implementation maintains control smoothness and avoids unrealistic high-frequency responses while preserving full-range maneuverability of the strake fins.

The LQR controller operates in a pure feedback mode, where the control inputs are derived from real-time state deviations of the drogue. No feedforward term is introduced in the present framework; however, future extensions may include disturbance-prediction-based feedforward control to further improve the system’s transient performance.

3.5. Control Performance Evaluation of the Stabilized Drogue Under Atmospheric Turbulence and Bow-Wave Disturbances

Based on the preceding sections, a dynamic simulation platform for the hose–drogue system was developed. The platform integrates the hose–drogue model, LQR controller, disturbance modules, and an aerodynamic module, and was employed to evaluate the performance of the strake-fin-stabilized drogue in mitigating the effects of atmospheric turbulence and receiver bow-wave disturbances.

To investigate the effect of the receiver bow wave during the docking phase and to evaluate the performance of the strake-fin-stabilized drogue under realistic approach conditions, a dynamic simulation procedure was established. The simulation couples the tanker wake field, the receiver-induced bow-wave disturbance, and the hose–drogue dynamic model. The main computational steps are summarized as follows:

1. Flow field preparation: The steady flow fields of both the tanker and the receiver are computed using CFD methods.

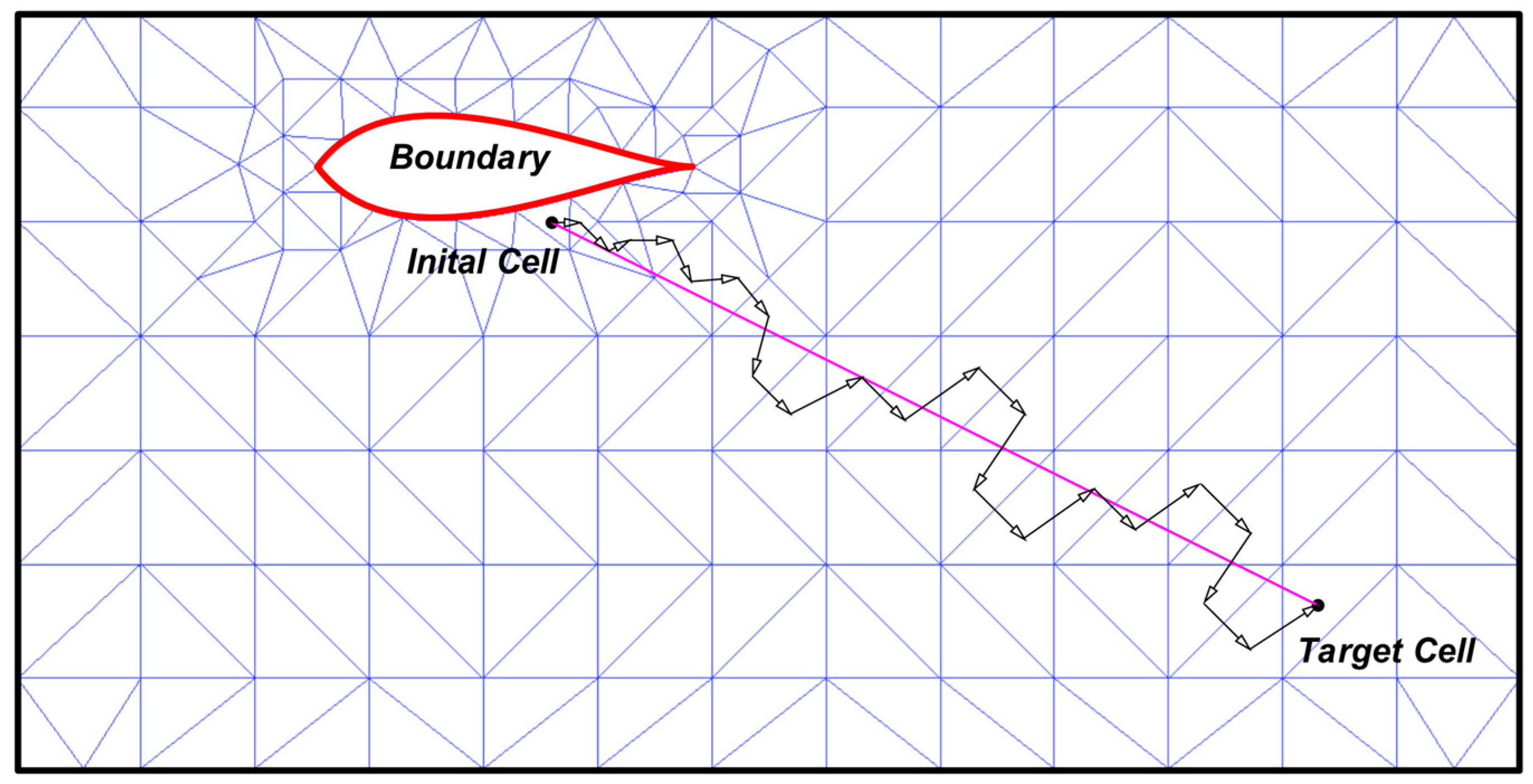

2. Baseline configuration: Using the neighboring-cell search algorithm (

Section 2.4), the tanker wake field is mapped onto the hose–drogue model to determine the initial equilibrium position of the system in the tanker wake.

3. Receiver approach modeling: At the start of the simulation (), the receiver probe is located at position . The drogue’s initial relative position is defined by ). As the receiver approaches, its position evolves according to a prescribed trajectory , driving a time-varying bow-wave disturbance field.

4. Force calculation: The local aerodynamic forces on each hose node and the drogue are obtained by mapping their instantaneous positions into the receiver flow field using the neighboring-cell algorithm.

5. Dynamic update: These disturbance forces are incorporated into the hose–drogue dynamic equations within the tanker wake, and the new node and drogue positions are solved at each time step.

6. Iteration: Steps 4 and 5 are repeated as the receiver moves closer according to , resulting in the continuous evolution of the drogue’s displacement under the combined influence of the tanker wake and receiver bow wave.

The simulation parameters used in this section are summarized in

Table 6 to ensure clarity and reproducibility. This configuration reflects a typical medium-speed flight regime used to evaluate the dynamic response and control performance of the proposed strake-fin drogue system. The simulations assumed that atmospheric conditions, as well as the drogue’s position and attitude, were measured with high accuracy to provide a reliable assessment of control effectiveness.

It is worth noting that the CFD flow fields are precomputed and stored as aerodynamic databases, and only neighbor-cell search and flow-field interpolation are performed during dynamic simulations. This approach minimizes computational overhead while preserving the key aerodynamic interactions. For a typical 7 s simulation with 40 hose nodes, the total CPU time is approximately 1 h on a 24-core workstation, which is orders of magnitude more efficient than fully coupled CFD–FSI methods.

To quantitatively assess drogue stabilization performance, the peak displacement amplitude in both the vertical and lateral directions was used as the primary evaluation metric. The suppression ratio was defined as the relative reduction in the maximum displacement amplitude after control activation.

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed stabilization system, the simulations were carried out under four disturbance scenarios, including tanker wake, receiver bow wave, atmospheric turbulence, and their combined effects.

The simulation results are presented in the following figures to illustrate the stabilized drogue response under different disturbance environments.

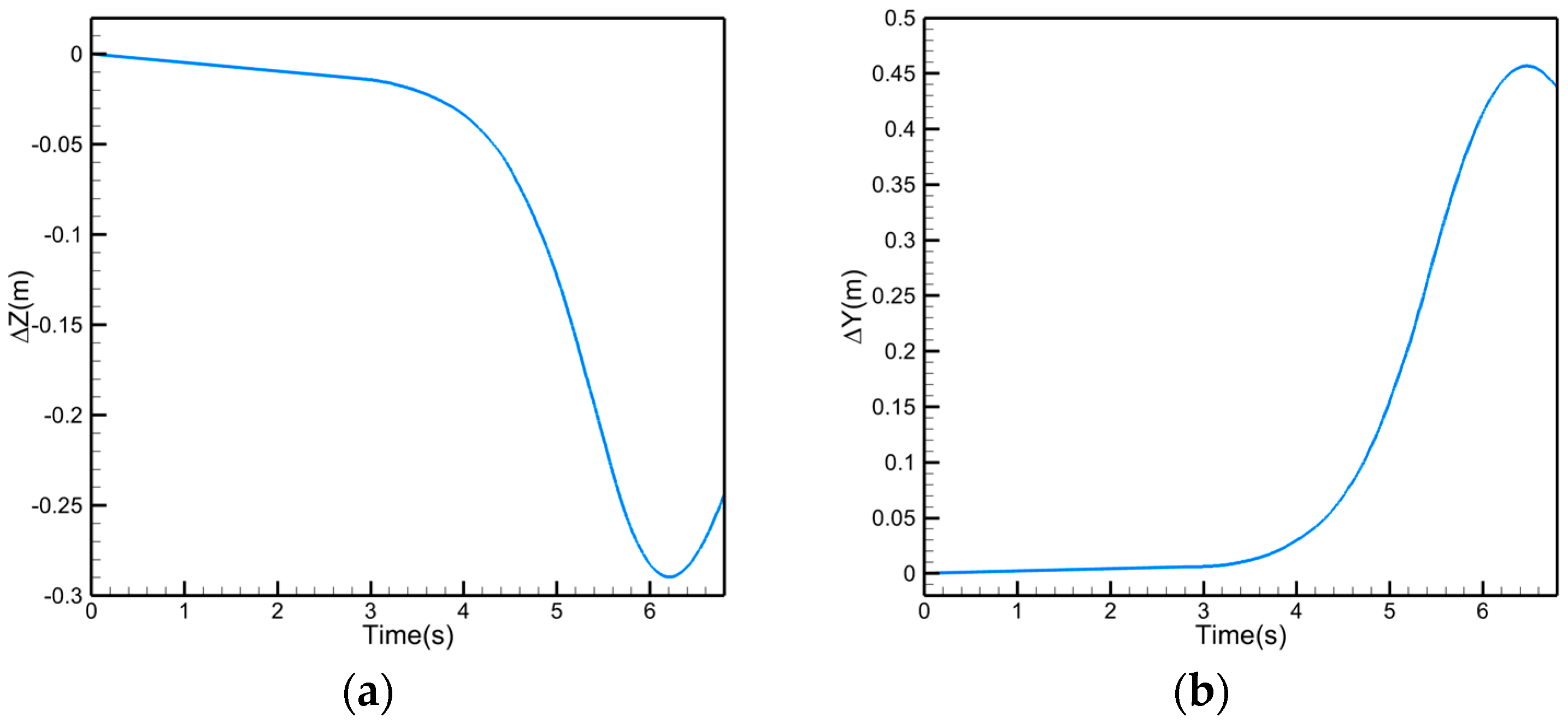

Figure 17 shows the vertical and lateral displacements of the drogue under the combined influence of tanker wake and receiver bow-wave disturbances. At

, the receiver aircraft begins to approach the drogue from an initial distance of

at a velocity of

. As the probe moves closer, the airflow around the receiver nose pushes the drogue away, causing it to drift upward and outward (with the positive

-axis directed downward and the positive

-axis directed to the right). This shift is attributed to the pressure rise and flow acceleration around the receiver nose, which modifies the local velocity field near the drogue.

Unlike the steady superposed flow field applied in

Section 2.7, this simulation resolves the time-accurate evolution of drogue displacement during the moving receiver’s approach. The results indicate that the bow wave effect induces a gradual but significant displacement, with the drogue drifting by approximately 0.3 m vertically and 0.45 m laterally at the end of the approach. This highlights the directional and cumulative nature of bow-wave disturbances, which can substantially degrade docking accuracy if not compensated for by active control mechanism.

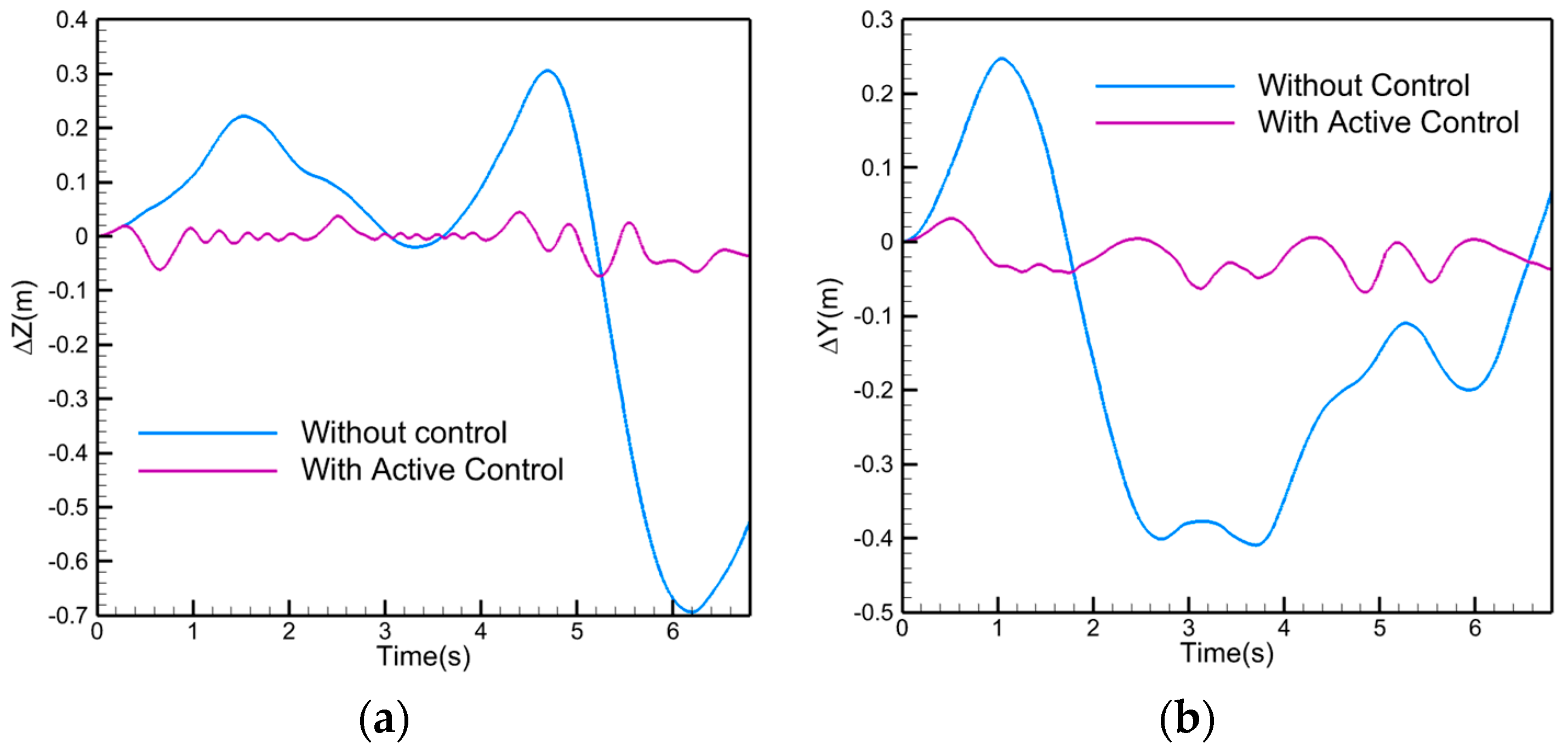

Figure 18 illustrates the time histories of drogue displacement under severe atmospheric turbulence, both with and without active control. Without control, turbulence induces oscillation amplitudes exceeding

m in the vertical direction and

m laterally, which are sufficient to push the drogue outside the acceptable capture envelope. With the proposed LQR-based control strategy, the oscillation amplitudes are effectively suppressed to below

m, demonstrating a significant enhancement in disturbance resistance. This result confirms that atmospheric turbulence plays a dominant role in destabilizing the drogue, and effective active stabilization is crucial to ensure successful docking under realistic operational conditions.

To evaluate the performance of the stabilization system under the most adverse operational conditions,

Figure 19 illustrates the drogue response when subjected simultaneously to tanker wake, receiver bow wave, and severe atmospheric turbulence. Without active control, the drogue exhibits large-amplitude oscillations, with maximum deviations reaching approximately

in the vertical direction and

in the lateral direction, indicating a high level of instability during docking. When the LQR-based active control system is activated, the drogue exhibits only small-amplitude oscillations, with deviations from the reference position remaining within

. This corresponds to an 80% reduction in peak displacement amplitude relative to the uncontrolled case, representing the decrease in the maximum observed deviations before and after control activation.

The stabilized drogue maintains its positional deviation within ±0.1 m under all combined disturbance conditions. This tolerance is consistent with the NASA Autonomous Aerial Refueling Demonstration (AARD) capture region criterion [

31], which defines a cylindrical capture radius (

) around the drogue axis as the spatial envelope for successful docking. When the receiver probe remains within this radius, a 90% docking success rate can be achieved with minimal lateral and vertical velocities, whereas motion beyond the miss distance (

) is classified as failed capture.

As shown in

Figure 20, the present study adopts a capture radius of (

) for the actively stabilized drogue, corresponding to the effective engagement envelope of the refueling system. The simulated positional deviations remain well within this limit, confirming compliance with established safety tolerances for probe–drogue docking.

The significance of this displacement suppression is twofold. First, reducing drogue oscillation amplitudes by more than ensures that the drogue remains inside the capture envelope during docking, directly improving engagement reliability. Second, the reduction in positional deviations minimizes the required corrective maneuvers by the receiver, improving operational safety margins and tolerance to external disturbances.

Therefore, the proposed active stabilization strategy not only suppresses drogue oscillations by more than 80%, but also ensures safe and reliable aerial refueling operations under complex disturbance environments.