Spitzer Resurrector Mission: Advantages for Space Weather Research and Operations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mission Objectives

2.1. SRM-Science Objectives

- Demonstrate remote sensing and reconstruction of CME magnetic fields (Faraday rotation);

- Understand the evolution of CME plasma and magnetic field in the inner heliosphere (Imager, Faraday rotation);

- Improve solar energetic particles (SEP) time-of-arrival, peak, and fluence predictions for cislunar space (SEP suite);

- Improve CME time-of-arrival predictions (Imager, Faraday rotation);

- Test real-time monitoring of solar wind impacting Earth (Imager, Faraday rotation);

- Improve forecasting of CME and SEP events (Imager, SEP suite).

3. Mission Design

3.1. Orbit, Trajectory Past Earth-Sun L4, and Station-Keeping near Earth-Sun L3

3.2. Strawman Payloads

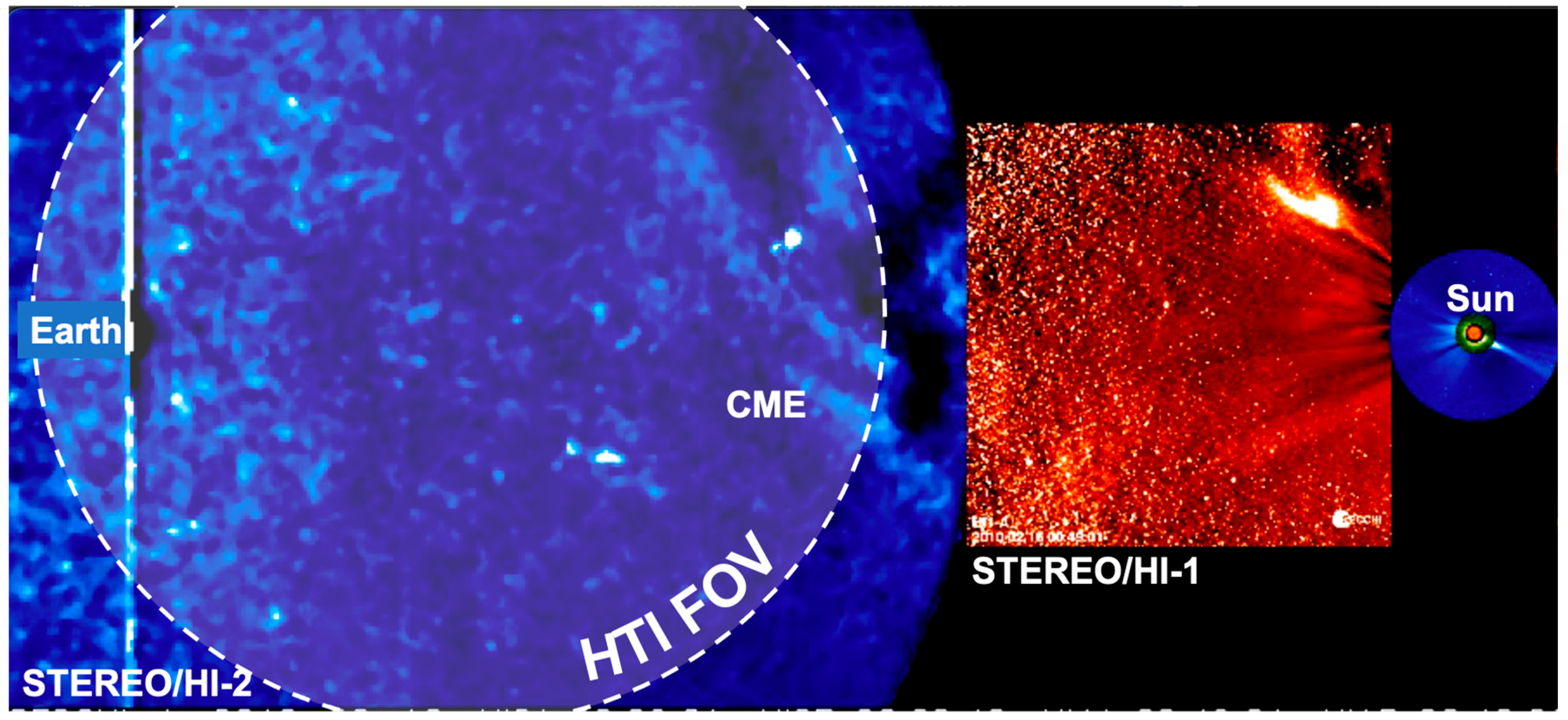

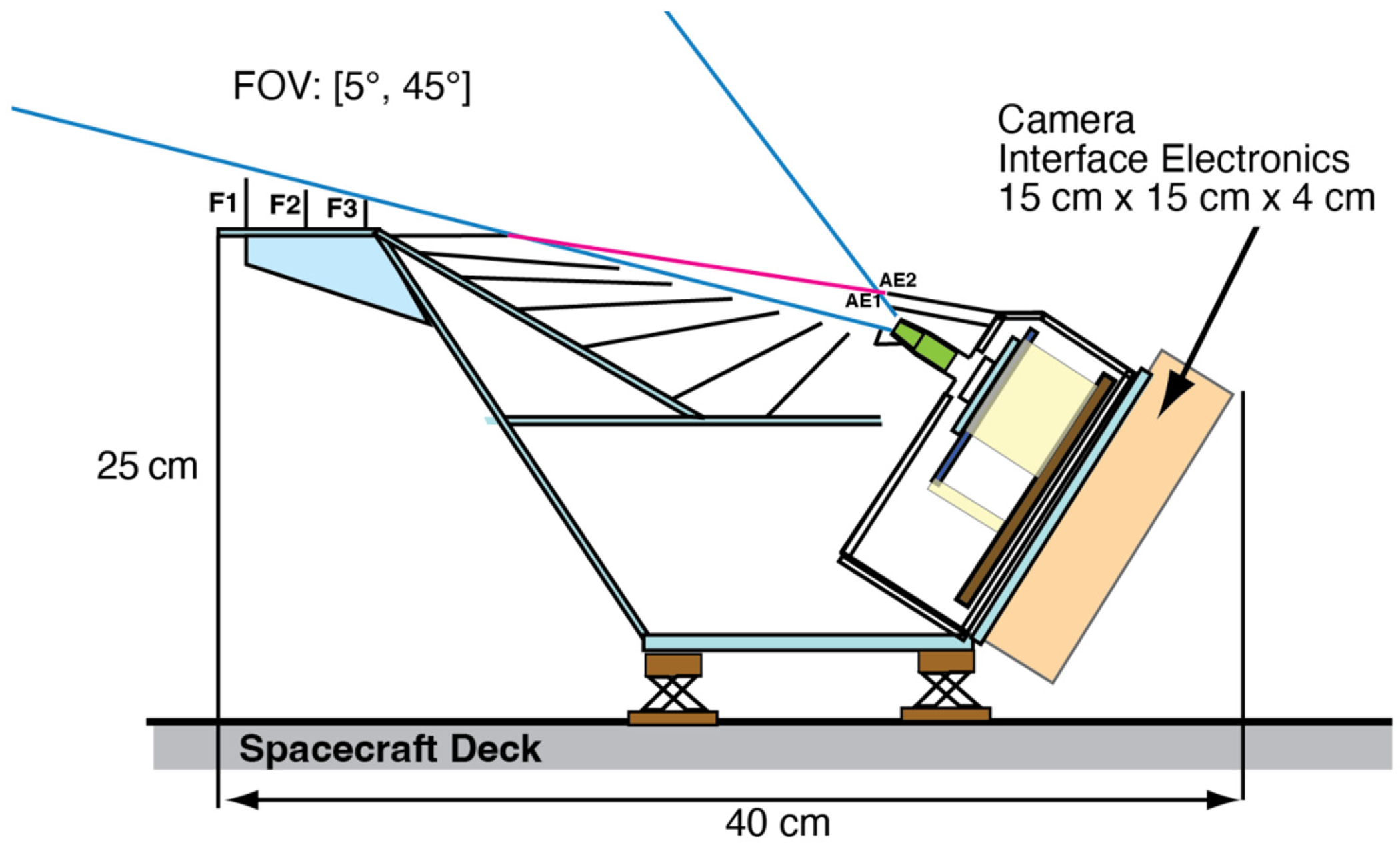

3.2.1. Heliospheric Transient Imager (HTI) Image

3.2.2. Faraday Rotation Experiment (FRE)

3.2.3. Solar Energetic Particles Suite (SEPS)

3.3. Concept of Operations

3.4. Technology Development

3.4.1. Virtual Machine Language Sequencing 3.0 [TRL-9] and AutoNav Mark 4 [TRL-6]

3.4.2. High Delta-V Maneuvering

3.5. Programmatics

3.5.1. Operational Readiness of Spitzer

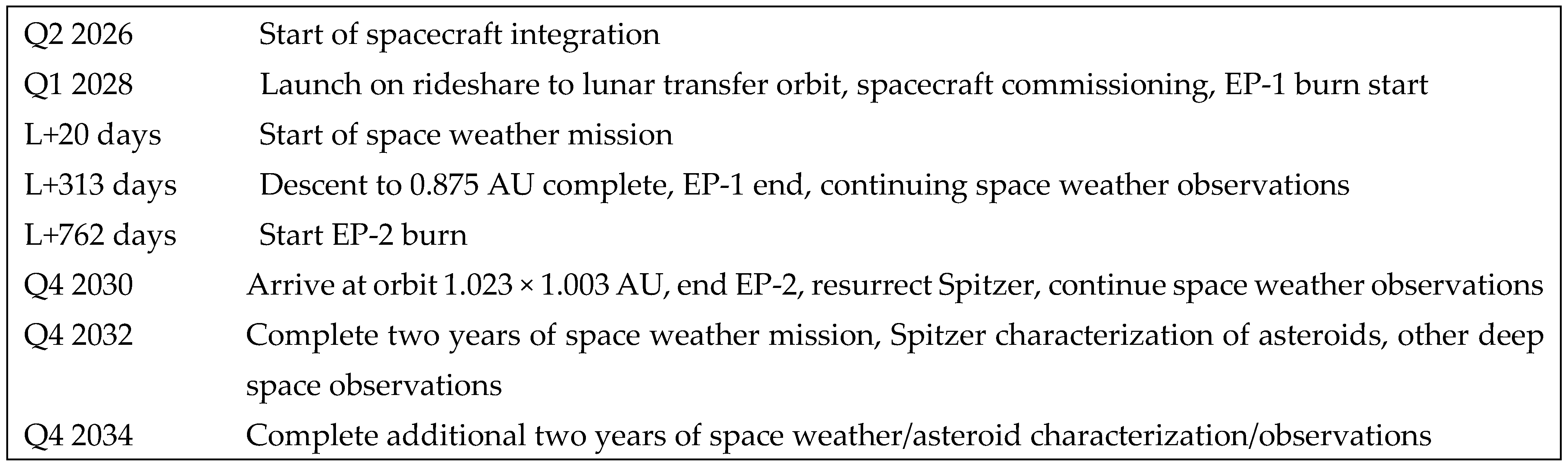

3.5.2. Schedule

3.5.3. Rideshare

3.5.4. Cost

3.5.5. Public/Private Partnership

4. Conclusions

- This is a ‘short fuse’ opportunity. To provide SWx observations for Artemis III, SRM needs to launch by 2027. This timeline is too short to maneuver through the usual NASA proposal cycle. Our proposed cross-agency government/public/private collaboration has the additional advantage of facilitating rapid procurement of scientific instrumentation, as well as providing quick access to technical, scientific, and public resources;

- SRM-SWx should be of interest to NOAA or others since its operational structure naturally enables innovative participation via ‘data buy,’ guest observer, and/or other options.

- Facilitate information exchange among the various Program Officers of government organizations involved in space projects. For example, being aware of potentially useful calls (or selections) to Heliophysics in other agencies should help with planning across the Division;

- Consider a ‘rapid response’ space hardware development program. It could be an agile version of the Mission-of-Opportunity program able to respond to launch/rideshare/host opportunities from other agencies with a short proposal/evaluation cycle (1–2 months, instead of years). DoD experience may be particularly useful for this type of program;

- Consider co-funding missions/hardware calls with DoD and NOAA so that successful Heliophysics concepts can be developed more efficiently and rapidly;

- Finalize a ‘data-buy’ policy and implementation document to engage the space industry in closing the SWx infrastructure gaps in the next decade and beyond.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grasso, C.A. Virtual Machine Language (VML) NASA Board Award; NASA Technical Report 40365; NASA Inventions and Contributions Board: Pasadena, CA, USA, 7 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United States Government. Space Weather Research-To-Operations and Operations-to-Research Framework. March 2022. Available online: https://testbed.swpc.noaa.gov/r2o2r/space-weather-r2o2r-framework (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Planning the Future Space Weather Operations and Research Infrastructure: Proceedings of a Workshop; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lock, P.D.; Grasso, C.A. Flight-ground integration: The future of operability. In Proceedings of the SpaceOps 2014 Conference, Pasadena, CA, USA, 5–9 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, M.W.; Roellig, T.L.; Low, F.J.; Rieke, G.H.; Rieke, M.; Hoffmann, W.F.; Young, E.; Houck, J.R.; Brandl, B.; Fazio, G.G.; et al. The Spitzer Space Telescope Mission. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2004, 154, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, C.A. Spitzer-Resurrector: Reviving the Last Great Observatory. 2024; Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Vourlidas, A.; Howard, R.; Plunkett, S.; Korendyke, C.; Thernisien, A.; Wang, D.; Rich, N.; Carter, M.; Chua, D.; Socker, D.; et al. The Wide-Field Imager for Solar Probe Plus (WISPR). Space Sci. Rev. 2015, 204, 83–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, G.S.; Sato, T.; Seidel, B.L.; Stelzried, C.T.; Ohlson, J.E.; Rusch, W.V. Pioneer 6: Measurement of Transient Faraday Rotation Phenomena Observed during Solar Occultation. Science 1969, 166, 596–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooi, J.E.; Fischer, P.D.; Buffo, J.J.; Spangler, S.R. VLA Measurements of Faraday Rotation through Coronal Mass Ejections. Sol. Phys. 2017, 292, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooi, J.E.; Wexler, D.B.; Jensen, E.A.; Kenny, M.N.; Nieves-Chinchilla, T.; Wilson, L.B.; Wood, B.E.; Jian, L.K.; Fung, S.F.; Pevtsov, A.; et al. Modern Faraday Rotation Studies to Probe the Solar Wind. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2022, 9, 841866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooi, J.E.; Ascione, M.L.; Reyes-Rosa, L.V.; Rier, S.K.; Ashas, M. VLA Measurements of Faraday Rotation Through a Coronal Mass Ejection Using Multiple Lines of Sight. Sol. Phys. 2021, 296, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E.A.; Russell, C.T. Faraday rotation observations of CMES. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L02103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlson, J.E.; Levy, G.S.; Stelzried, C.T. A Tracking Polarimeter for Measuring Solar and Ionospheric Faraday Rotation of Signals from Deep Space Probes. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 1974, 23, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, A.; Arge, C.N.; Staub, J.; StCyr, O.C.; Folta, D.; Solanki, S.K.; Strauss, R.D.T.; Effenberger, F.; Gandorfer, A.; Heber, B.; et al. A multi-Purpose Heliophysics L4 Mission. Space Weather 2021, 19, e2021SW002777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pacheco, J.; Wimmer-Schweingruber, R.F.; Mason, G.M.; Ho, G.C.; Sánchez-Prieto, S.; Prieto, M.; Martín, C.; Seifert, H.; Andrews, G.B.; Kulkarni, S.R.; et al. The Energetic Particle Detector: Energetic particle instrument suite for the Solar Orbiter mission. Astronomy Astrophys. 2020, 642, A7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, C.A. Techniques for simplifying operations using vml (virtual machine language) sequencing on mars odyssey and SIRTF. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings (Cat. No.03TH8652), Big Sky, MT, USA, 8–15 March 2003; pp. 8_3603–8_3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, C.A.; Riedel, J.E.; Vaughn, A.T. Reactive Sequencing for Autonomous Navigation Evolving from Phoenix Entry, Descent, and Landing. In Proceedings of the AIAA Space Operations Conference Proceedings, Huntsville, AL, USA, 25–30 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, C.A. VML 3.0 reactive rendezvous and Docking Sequencer for Mars Sample Return. In Proceedings of the SpaceOps 2014 Conference, Pasadena, CA, USA, 5–9 May 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peer, S.; Grasso, C.A. Spitzer Space Telescope Use of Virtual Machine Language. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 5–12 March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Riedel, J.; Eldred, D.; Kennedy, B.; Kubitscheck, D.; Vaughan, A.; Werner, R.; Bhaskaran, S.; Synnott, S. AutoNav Mark 3: Engineering the Next Generation of Autonomous Onboard Navigation and Guidance. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Keystone, CO, USA, 21–24 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Riedel, J.; Werner, R.; Vaughan, A.; Mastrodemos, N.; Huntington, G.; Grasso, C.; Wang, T.-C.; Myers, D.; Gaskell, R.; Bayard, D. Configuring the Deep Impact AutoNav System for Lunar, Comet and Mars Landing. In Proceedings of the AIAA Astrodynamics Specialist Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 18–21 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Usman, S.M.; Fazio, G.G.; Grasso, C.A.; Hickox, R.C.; Lance, C.; Rideout, W.B.; Singh, D.M.; Smith, H.A.; Vourlidas, A.; Hora, J.L.; et al. Spitzer Resurrector Mission: Advantages for Space Weather Research and Operations. Aerospace 2024, 11, 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11070560

Usman SM, Fazio GG, Grasso CA, Hickox RC, Lance C, Rideout WB, Singh DM, Smith HA, Vourlidas A, Hora JL, et al. Spitzer Resurrector Mission: Advantages for Space Weather Research and Operations. Aerospace. 2024; 11(7):560. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11070560

Chicago/Turabian StyleUsman, Shawn M., Giovanni G. Fazio, Christopher A. Grasso, Ryan C. Hickox, Cameo Lance, William B. Rideout, Daveanand M. Singh, Howard A. Smith, Angelos Vourlidas, Joseph L. Hora, and et al. 2024. "Spitzer Resurrector Mission: Advantages for Space Weather Research and Operations" Aerospace 11, no. 7: 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11070560

APA StyleUsman, S. M., Fazio, G. G., Grasso, C. A., Hickox, R. C., Lance, C., Rideout, W. B., Singh, D. M., Smith, H. A., Vourlidas, A., Hora, J. L., Melnick, G. J., Ashby, M., Tolls, V., Willner, S., & Benitez, S. (2024). Spitzer Resurrector Mission: Advantages for Space Weather Research and Operations. Aerospace, 11(7), 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11070560