Comprehensive Tool for Assessing Farmers’ Knowledge and Perception of Climate Change and Sustainable Adaptation: Evidence from Himalayan Mountain Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

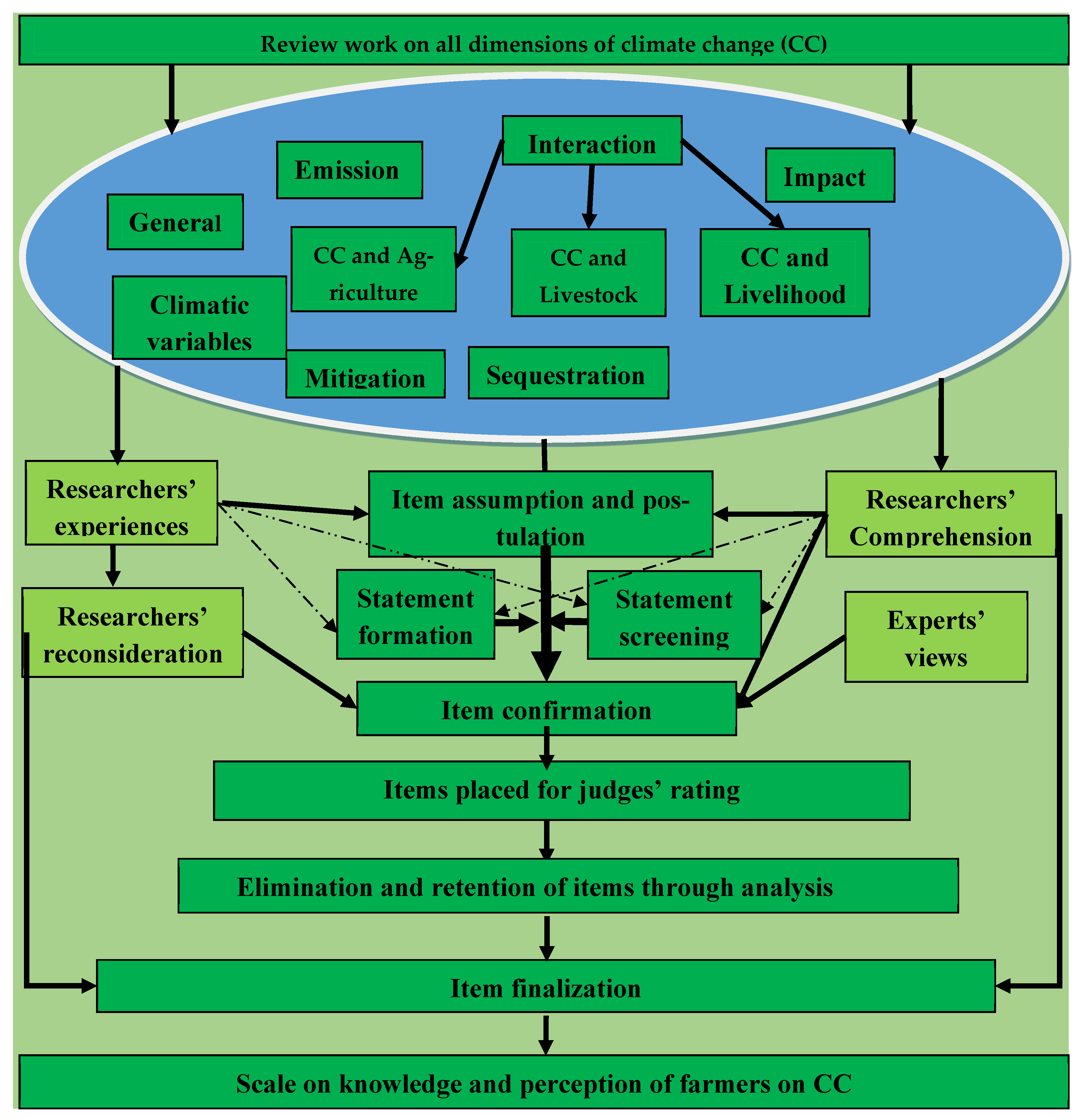

2.1. Item/Statement Selection

2.2. Scoring

2.3. Construction of Questionnaire

2.4. Criteria for Selection of Judge

2.5. Collection of Judges’ Responses

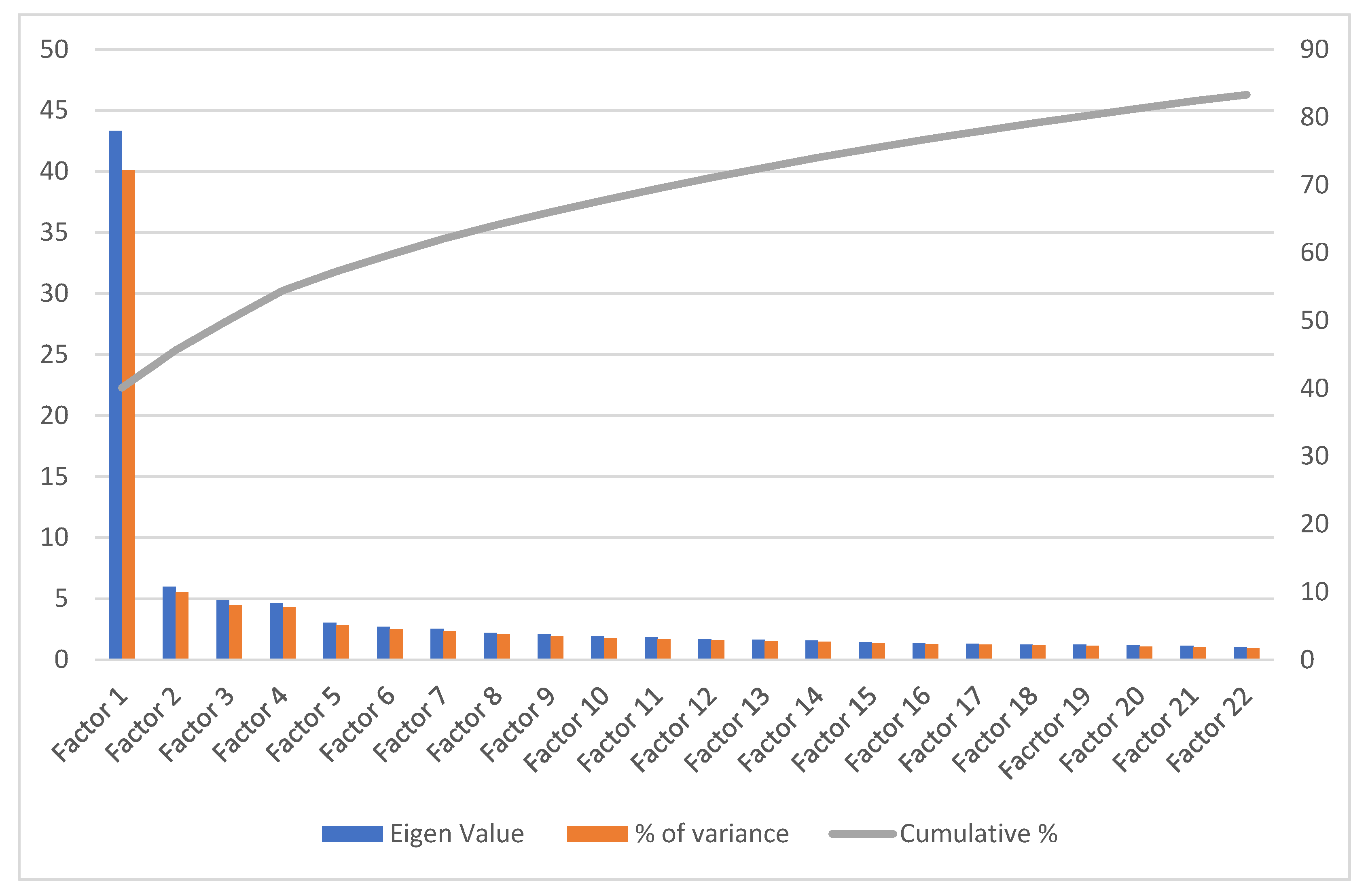

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Consistency Assessment

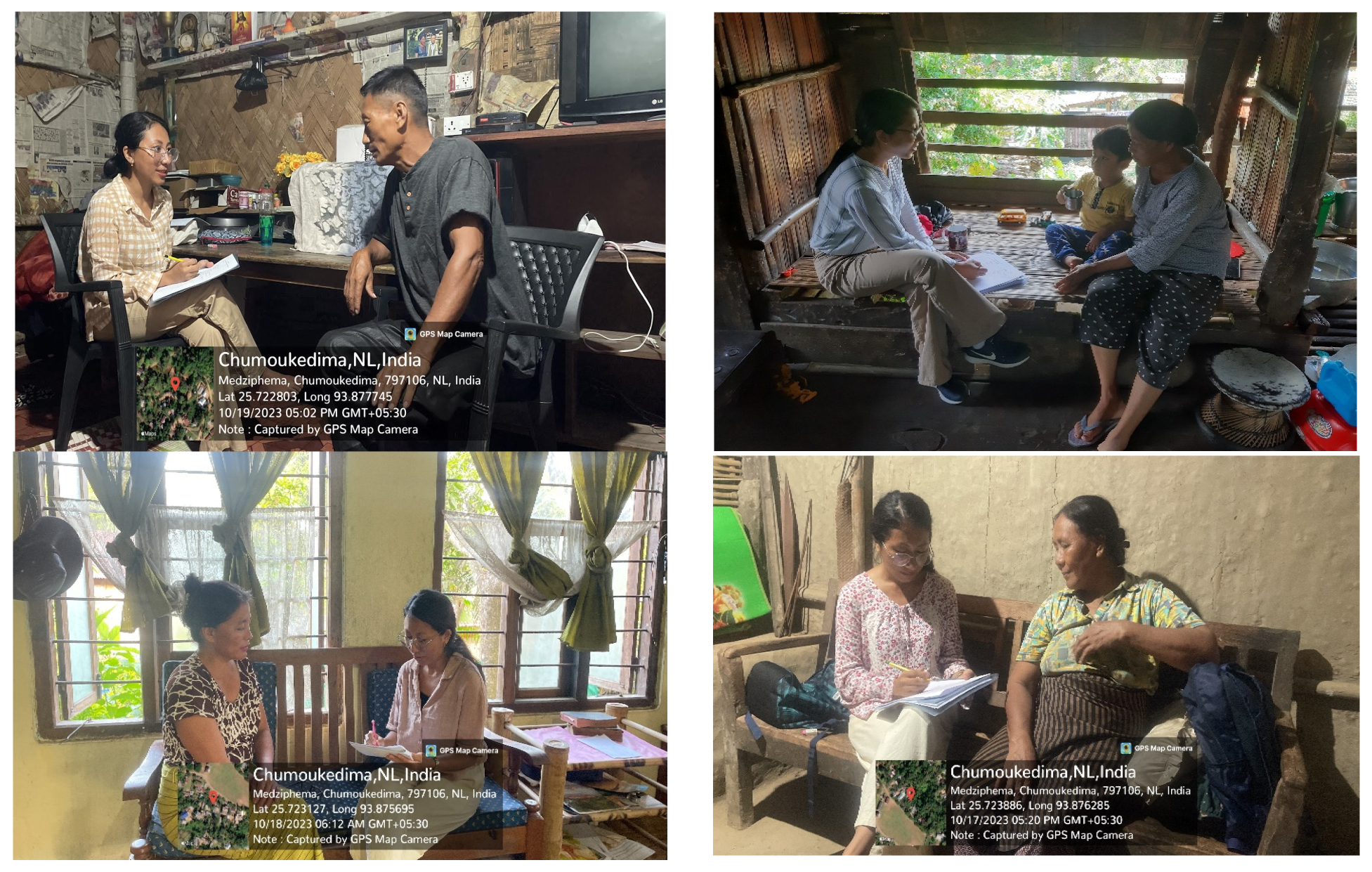

2.8. Application of Scale for Assessment of Farmers’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Climate Change

2.9. Criteria for Selection of Farmers

2.10. Ethical Statement

3. Results

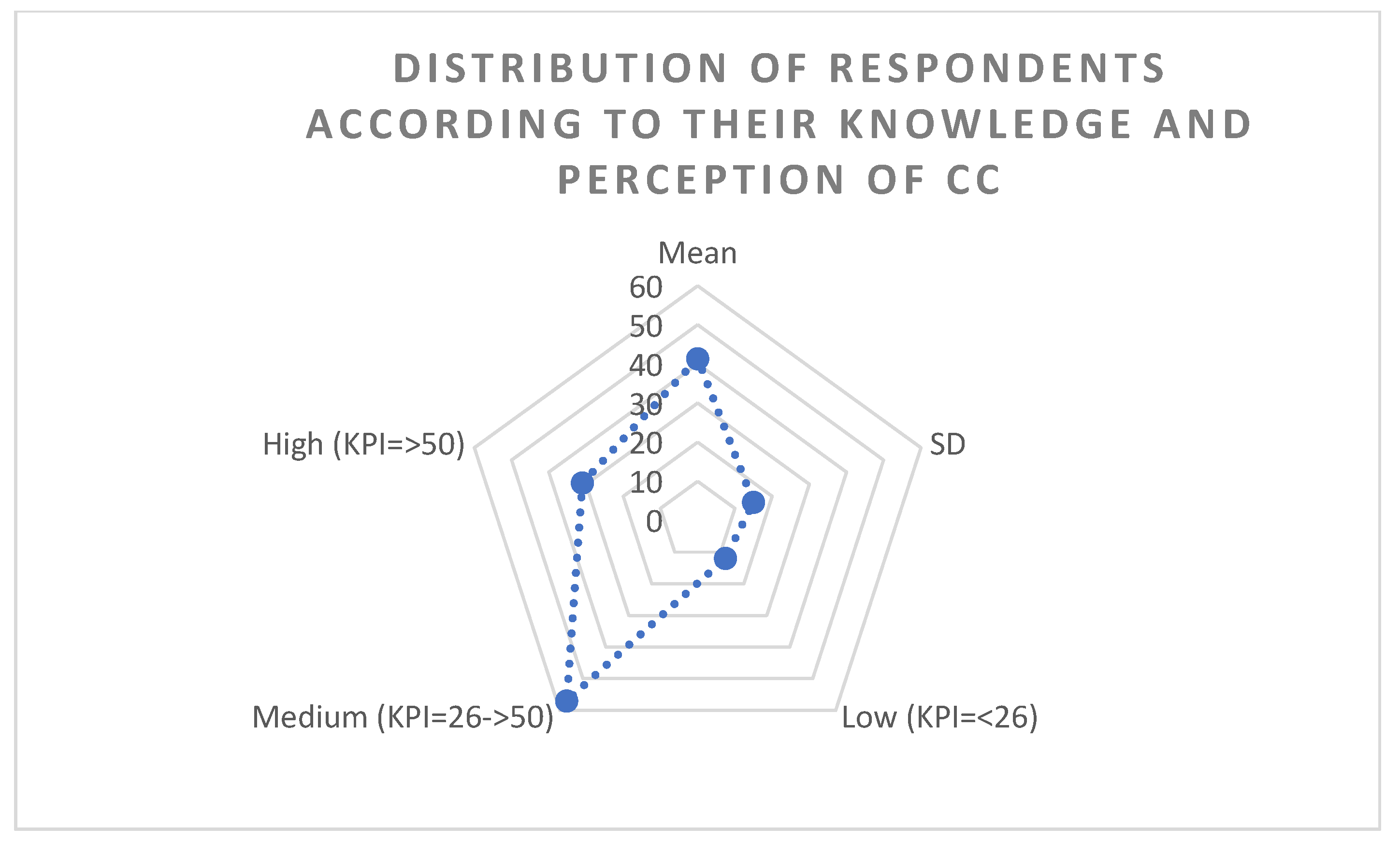

Application of Scale for Assessment of Farmers’ Awareness, Knowledge, and Perceptions of CC

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge and Perception

4.2. Sustainable Adaptation

4.3. Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture

4.4. Occurrence of Climate Hazards

4.5. Awareness/Knowledge of Climate Change

4.6. Impact of Climate Change on Livelihood

4.7. Enhancing the Capacity of Farmers

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC; Portner, H.O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Okem, K., Rama, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; p. 3056. Available online: https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6/wg2/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Chanda, N.; Chintalacheruvu, M.R.; Choudhary, A.K. Exploring climate-change impacts on streamflow and hydropower potention: Insights from CMIP6 multi-GCM analysis. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Oshiro, K.; Zhao, S.; Sasaki, K.; Takakura, J.; Takahashi, K. Potential side effects of climate change mitigation on poverty and countermeasures. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 2245–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, J.D.; Pirzadeh, A.; Irfan, M.; Solorzano, J.; Stone, B.; Xiong, Y.; Hanna, T.; Hughes, B.B. How many people will live in poverty because of CC? A macro-level projection analysis to 2070. Clim. Change 2023, 176, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L.A., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, N.K.; Babu, S.C. Mapping Indian Agricultural Emissions Lessons for Food System Transformation and Policy Support for Climate-Smart Agriculture. IFPRI Discuss. Pap. 2017, 01660. Available online: www.ifpri.org (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Stewart, S.A.; Arbuthnott, K.D.; Sauchyn, D.J. Climate change perceptions and Associate Sharacteristics in Canadian Prairie Agricultureal Producers. Challenges 2023, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.; Wreford, A.; Knook, J.; Teixeira, E.; Monge, J.; Parker, A. Diversification as a climate change adaptation strategy in viticulture systems: Winegrowers’ insights from Marlboroug, New Zealand. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 49, 494–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, S.; Chaudhary, R.; Sharma, S.; Janjhua, Y.; Thakur, P.; Sharma, P.; Keprate, A. Exploring the dynamics of climate-smart agriculture practices for sustainable resilience in a changing climate. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 24, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, S.; Burton, P.; Mackey, B. The experience and perceptions of farmers about the impact of climate change and variability on crop production: A review. Clim. Dev. 2019, 12, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayadas, A.; Ambujam, N.K. Research and design of a farmer resilience index in coastal farming communities of Tamil Nadu, India. J. Water Clim. Change 2021, 12, 3143–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugambiwa, S.S.; Makhubele, J.C. Indigenous knowledge systems based climate governance in water and land resource management in rural Zimbabwe. J. Water Clim. Change 2021, 12, 2045–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, N.; Feit, B.; Kihara, J.; Luttermoser, T.; May, W.; Midega, C.; Öborn, I.; Poveda, K.; Sileshi, G.W.; Zewdie, B.; et al. Climate change and ecological intensification of agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa—A systems approach to predict maize yield under push-pull technology. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 352, 108511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesam, M.; Roshan, G.; Grab, S.W.; Shabahrami, A.R. Comparative assessment of farmers’ perception on drought impacts: The case of a coastal lowland versus adjoining mountain foreland region of northern Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 143, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Tiwari, P. climate change vulnerability assessment for adaptation planning in Uttarakhand, Indian Himalaya. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 114, 104938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Kumar, V.; Saharia, M. Analysis of rainfall and temperature trends in northeast India. Int. J. Clim. 2013, 33, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimri, A.P.; Niyogi, D. Regional climate model application at subgrid scale on Indian monsoon over the western Himalyas. Int. J. Climatol. 2013, 33, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgaonkar, H.; Ram, S.; Sikder, A. Assessment of tree-ring analysis of high-elevation Cedrus deodara D. Don from Western Himalaya (India) in relation to climate and glacier fluctuations. Dendrochronologia 2009, 27, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, P.; Shrestha, S.; Babel, M.S. Forecasting climate change impacts and evaluation of adaptation options for maize cropping in the hilly terrain of Himalayas: Sikkim, India. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2015, 121, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of India. Governance for Sustaining Himalayan Ecosystem. GSHE Guidelines and Best Practices; Ministry of Environment & Forests, Govind Ballabh Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment & Development, Government of India: Almora, India, 2006. Available online: http://gbpihed.gov.in/PDF/Publication/G-SHE_Book.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Dahal, K.R.; Dahal, P.; Adhikari, R.K.; Naukkarinen, V.; Panday, D.; Bista, N.; Helenius, J.; Marambe, B. climate change Impact and Adaptation in a Hill Farming System of the Himalayan Region: Climate Trends, Farmers’ Perceptions and Practices. Climate 2023, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, N.K.; Benjongtoshi. Sustainable performance of French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivation, a livelihood component in Eastern Himalayan Region. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2247784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ado, A.M.; Leshan, J.; Savadogo, P.; Bo, L.; Shah, A.A. Farmers’ awareness and perception of climate change impacts: Case study of Aguie district in Niger. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 2963–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadwal, S.; Sharma, G.; Gorti, G.; Sen, S.M. Livelihoods, gender and climate change in the Eastern Himalayas. Environ. Dev. 2019, 31, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, O.W.; du Pont, P.; Gueguen-Teil, C. Perception of climate-related risk in Southeast Asia’s power sector. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.A.; Netherton, C.; Benson, D.; Rahman, R.M.; Salehin, M.A. Governance Perspective for climate change Adaptation: Conceptualizing the Policy-Community interface in Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 137, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeiryte, A.; Krikstolaitis, R.; Liobikiene, G. The differences of climate change perception, responsibility and climate-friendlybehaviour among generations and the main determinants of youth’s climate-friendly actions in the EU. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sertse, S.F.; Khan, N.A.; Shah, A.A.; Liu, Y.; Naqvi, S.A.A. Farm households’ perceptions and adaptation strategies to climate change risks and their determinants: Evidence from Raya Azebo district, Ethiopia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 60, 102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijndam, S.J.; Botzen, W.W.; Endendijk, T.; de Moel, H.; Slager, K.; Aerts, J.C.J.H. A look into out future under climate change? Adaptation and mitigation intentions following extreme flooding in the Netherlands. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 95, 103840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, N.K.; Rilung, T.; Das, L.; Kumar, P. Assessing climate change and its impact on kiwi (Actinidia deliciosa Chev.) production in the Eastern Himalayan Region of India through a combined approach of people perception and meteorological data. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 2347–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemandez Lopez, J.A.; Puerta-Cortes, D.X.; Andrade, H.J. Predictive analysis of Adaptation to Drought of Farmers in the central Zone of Colombia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, P.; Behera, B. Do farmers perceive climate change clearly? An analysis of meteorological data and farmers’ perceptions in the sub-Himalayan West Bengal, India. J. Water Clim. Change 2022, 13, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolletti, M.; Maschietto, F.; Moreno, T. Integrating social learning into climate change adaptation public policy cycle: Building upon from experiences in Brazil and the United Kingdom. Environ. Dev. 2020, 33, 100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Radke, J.; Chen, F.S.; Sachdeva, S.; Gershman, S.J.; Luo, Y. How do we reinforce climate action? Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 1503–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B.S.; Engelhart, M.D.; Furst, E.J.; Hill, W.H.; Krathwohl, D.R. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. In Handbook I: Cognitive Domain; David Mckay Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Government of India. Census Data. 2011. Available online: www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-common/censusdataonline.html (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Lalthamawii; Patra, N.; Sailo, Z. Knowledge and Adoption Status of Recommended Practices of Rice by Farmers in Mizoram, India. Indian Res. J. Ext. Educ. 2022, 22, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, N.; Lalthamawii; Rohith, G.; Das, S. Socio-economic and Psychological Status of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Growers and Constraints in Cultivation: Evidence from Mizoram, India. J. Community Mobilization Sustain. Dev. 2023, 18, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiller, R.; Booth, A.M.; Cowan, E. Risk Perception and Risk Realities in Forming Legally Blinding Agreements: The Governance of Plastics. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 134, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijhani, A.; Sinha, V.S.P.; Vishwakarma, C.A.; Singh, P.; Pandey, A.; Govindan, M. Study of stakeholders’ perceptions of climate change and its impact on mountain communities in central Himalaya, India. Environ. Dev. 2023, 46, 100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitew, A.B.; Minale, A.S. Smallholder farmers’ perceptions of climate variability and its risks across agroecological zones in the Ayehu watershed, Upper Blue Nile. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 25, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.O.; Carlisle, L.; Lloyd, M.G.; Sayre, N.F.; Bowles, T.M. Understanding farmers knowledge of soil and soil management: A case study of 13 organic farms in an agricultural land scape of northern California. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 48, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valkengoed, A.; Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G. Development and validation of a climate change perceptions scale. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 76, 101652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounis, M.; Madani, A.; Boutebal, S.E. Perception and Knowledge of Algerian Students about Climate change and its Putative Relationship with the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Preliminary Cross-Sectional Survey. Climate 2023, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudet, H.; Giordono, L.; Zanocco, C.; Satein, H.; Whitley, H. Event attribution and partisanship shape local discussion of climate change after extreme weather. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Poortinga, W.; Butler, C.; Pidgeon, N.F. Perception of climate change and willingness to save energy related to flood experience. Nat. Clim. Change 2011, 1, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, I.; Faria, S.H.; Neumann, M.B. climate change Perception: Driving Forces and Their Interactions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 108, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayamajhee, V.; Guo, W.; Bohara, A.K. The perception of climate change and the demand for weather- index microinsurance: Evidence from a contingent valuation survey in Nepal. Clim. Dev. 2021, 14, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheval, S.; Bulai, A.; Croitoru, A.-E.; Dorondel, Ș.; Micu, D.; Mihăilă, D.; Sfîcă, L.; Tișcovschi, A. climate change perception in Romania. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 149, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, A.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Nalakurthi, S.-R.; Gharbia, S. Public perceptions of climate risks, vulnerability, and adaptation strategies: Fuzzy cognitive mapping in Irish and Spanish living labs. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 26, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Zwickle, A.; Walpole, H. Developing a Broadly Applicable Measure of Risk Perception. Risk Anal. 2019, 39, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, A.G.; Pearce, S. A Beginner’s Guide to Factor Analysis Focusing on Exploratory Factor Analysis. Tutor. Quant. Meth. Psychol. 2013, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, A.; O’Connor, R.E.; Böhm, G.; Hanss, D.; Bodi, O.; Ekström, F.; Halder, P.; Jeschke, S.; Mack, B.; Qu, M.; et al. Casual thinking and support for climate change policies: International survey findings. Glob. Environ. Change 2012, 22, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, S.; Kashima, Y.; Walker, I.; O’Neill, S. Investigating the effects of knowledge and ideology on climate change beliefs: Knowledge, ideology, and climate change beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Y.; Gifford, R. Free Market ideology environmental degradation: The case of belief in global climate change. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S. Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: A cross-European analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 55, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S. The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Brewer, M.B.; Hayes, B.K.; McDonald, R.I.; Newell, B.R. Predicting climate change risk perception and willingness to act. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, J.A.; Stok, F.M.; de Wit, J.B.; Bal, M. Climate change skepticism questionnaire: Validation of a measure to assess doubts regarding CC. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 89, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaker, J.; Richardson, L.M.; Holmes, D.C. Australians’ perceptions about health risks associated with CC: Exploring the role of media in a comprehensive climate change risk. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 89, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, A.K.; Burman, R.R.; Lenin, V.; Sajesh, V.K.; Sharma, P.R.; Sarkar, S.; Sharma, J.P.; Iquebal, A. Scale construction to measure the attitude of farmers towards IARI_post Office Linkage Extension Model. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2019, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, N.K.; Babu, S.C. Institutional and policy process for climate-smart agriculture: Evidence from Nagaland State, India. J. Water Clim. Change 2022, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, N.K.; Nina, N.; Pathak, T.B.; Karak, T.; Babu, S.C. Nutrition Security and Homestead Gardeners: Evidence from the Himalayan Mountain Region. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2499. Available online: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 (accessed on 27 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Abunyewah, M.; Erdiaw-Kwasie, O.M.; Acheampong, O.A.; Arhin, P.; Okyere, S.A.; Zanders, K.; Frimpong, L.K.; Byrne, K.M.; Lassa, J. Understanding climate change adaptation in Ghana: The role of climate change anxiety, experience and knowledge. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 150, 103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, N.K. Extension Management by Agricultural Development Officers of West Bengal. Ph.D. Thesis, Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Nadia, India, 2004. Available online: http://krishikosh.egranth.ac.in/handle/1/5810007465 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Patra, N.K.; Odyuo, M.N.; Mondal, S. Indicators of Effective Management of Development Work by Non Government Organizations in Nagaland, India. Int. J. Ext. Educ. 2015, XI, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- The Land of Opportunity-Chumoukedima. 2025. Available online: https://chumoukedima.nic.in/about-district (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Gateway of Nagaland-District Dimapur. 2025. Available online: https://dimapur.nic.in/about-district/#:~:text=A%20large%20area%20of%20the,44%E2%80%B2%2030%E2%80%9D%20E%20Longitude (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Okafor, C.C.; Ajaero, C.C.; Madu, C.N.; Nzekwe, C.A.; Otunomo, F.A.; Nixon, N.N. Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Nigeria: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’SOuvi, K.; Adjakpenou, A.; Sun, C.; Ayisi, C.L. climate change perceptions, impacts on the catches, and adaptation practices of the small-scale fishermen in Togo’s coastal area. Environ. Dev. 2024, 49, 100957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.J.; Metzger MJMacleod, C.J.A.; Helliwell, R.C.; Pohle, I. Understanding knowledge needs for Scotland to become a resilient Hydro Nation: Water stakeholder perspectives. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, M.; Hannay, J.; Feick, R.D.; Caldwell, W. Social psychological factors drive farmers’ adoption of environmental best management practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 350, 119491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J.E., Calvo Buendia, V., Masson-Delmotte, H.O., Portner, P., Zhai, R., Slade, S., Connors, R., van Diemen, M., Ferrat, E., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhou, W.; Guo, S.; Deng, X.; Song, J.; Xu, D. The influence of peer effects on farmers’ response to climate change: Evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Clim. Change 2022, 175, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrat, P.; Simane, B. Framers’ perception of climate change and adaptation strategies in the Dabus watershed, North-West Ethiopia. Ecol. Process. 2018, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaki, M.Y.; Muench, S.; Kaechele, H.; Bavorova, M. climate change knowledge and perception among farming households in Nigeria. Climate 2023, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuvanshi, R.; Ansari, M.A. A scale to measure farmers’ risk perceptions about climate change and its impact on agriculture. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2019, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, N.; Terre, S. On the Nature of Naturalness? Theorizing Nature for the Study of Public Perceptions of Novel Genomic Technologies in Agriculture and Conservation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaican, D.; Nichersu, I.; Nichersu, I.I.; Peerce, A.; Wilhelmi, O.; Laborgrie, P.; Bratfanof, E. Creating Knowledge about Food-Water-Energy Nexus at local scale: A participatory approach in Tulcea Romania. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 141, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Protection Issues Faced by Women Farmers in Pakistan-Study and Strategy Solutions, Islamabad. 2024. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/c59fd3200c16-4411-9840-b076fdd67c64/content (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Gutman, V.; Frank, F.; Monjeau, A.; Peri, P.L.; Ryan, D.; Volante, J.; Apaza, L.; Scardamaglia, V. Stakeholder-based mdelling in climate change planning for the agriculture sector in Argentina. Clim. Policy 2023, 24, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehola, A.; Malkamaki, A.; Kosenius, A.-K.; Hurmekoski, E.; Toppinen, A. Risk Perception and Political Leading Explain the Preferences of Non-industries Private landowners for Alternative climate change Mitigation Strategies in Finnish Forests. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 137, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, S.; Begum, R.A.; Maulud, K.N.A.; Yaseen, Z.M. Households’ perceptions and socio-economic determinants of climate change awareness: Evidence from Selangor Coast Malaysia. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, S.; Gentle, P.; Khanal, U.; Wilson, C.; Rimal, B. A systematic review of Nepalese farmers’ climate change adaptation strategies. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockney, M.P. Farmers adapt to climate change irrespective of stated belief in CC: A California case study. Clim. Change 2022, 173, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, N.K.; Chophi, V.S.; Das, S. Knowledge level and adoption behavior of maize growers in selected districts of Nagaland, India. Indian J. Ext. Educ. 2023, 59, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, N.K.; Kense, P.-U. Study on Knowledge and Adoption of Improved Cultivation Practices of Mandarin (Citrus reticulata blanco) Growers in Nagaland, India. Indian J. Ext. Educ. 2020, 56, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, N.K.; Moasunep; Sailo, Z. Assessing socioeconomic and modernization status of rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) Growers: Evidence from Nagaland, North Eastern Himalayan Region, India. Indian Res. J. Ext. Educ. 2020, 20, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

| Items/Statements |

|---|

| * X14 Solar and renewable energy are emission-neutral/climate-friendly |

| * X33 The environment is getting warmer day by day |

| * X34 Frequency of unexpected climatic events has increased |

| * X37 Erratic precipitation during monsoon |

| * X41 Duration of the rainy season has shortened |

| * X50 Jhum (shifting cultivation) burning is emitting/adding GHGs |

| * X78 Climatic uncertainty has increased |

| Indicator (Name of Indicator) | Factor | Items/Statements | Factor Loading | Eigenvalue | Communality | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Overall = 0.985) Each Factor | ||||||

| I (Respondents’ Knowledge and perception of agricultural CC, emission of GHGs and mitigation strategy) | 1 | * x46 Proper composting of crop residue is a/an mitigation/adaptation strategy to climate change (CC) | 0.408 | 43.33 | 0.745 | 0.938 |

| x52 Rice cultivation is also adding N2O to the environment | 0.556 | 0.813 | ||||

| x54 Alternative dry and wet spells of rice fields is a mitigation measure to reduce the emission of GHGs from rice field | 0.545 | 0.879 | ||||

| x55 SRI has the potential to reduce the emission of GHGs from rice field | 0.526 | 0.790 | ||||

| ** x57 Root zone placement of Nitrogenous fertiliser is a mitigation measure to reduce the emission of N2O from crop field | 0.465 | 0.871 | ||||

| ** x59 Proper handling of animal urine is a measure to reduce the emission of GHG | 0.461 | 0.818 | ||||

| x60 Earth’s surface is an enormous reservoir of Carbon | 0.637 | 0.857 | ||||

| x61 Exposing/disturbing the soil surface is used to expose soil carbon, which is also a reason for CC | 0.778 | 0.877 | ||||

| x62 Ploughing is a means to expose soil carbon | 0.759 | 0.850 | ||||

| x63 Grazing is a reason to expose the earth’s surface | 0.713 | 0.881 | ||||

| x64 Zero or minimum tillage is desirable to adapt the emission due to disturbance of soil surface | 0.763 | 0.822 | ||||

| x65 Are you aware of C-sequestration | 0.564 | 0.826 | ||||

| ** x66 Crop cultivation is a practice of C-sequestration | 0.474 | 0.833 | ||||

| x67Agriculture (except some crops) is used to consider as GHG emission neutral | 0.566 | 0.854 | ||||

| x68 Eastern Himalayan region is more vulnerable to CC | 0.552 | 0.772 | ||||

| 13 | x43 Agriculture is highly vulnerable to CC | 0.743 | 1.63 | 0.888 | - | |

| 14 | ** x40 Annual rate of rainfall is inconsistent (with respect to previous years) | 0.451 | 1.59 | 0.774 | 0.759 | |

| * x53 Waterlogging rice cultivation is greatly responsible for CC | 0.444 | 0.828 | ||||

| x56 Split application of nitrogenous fertiliser is a mitigation measure to reduce the emission of N2O from rice field | 0.502 | 0.859 | ||||

| 15 | * x42 Agriculture is also emitting GHGs | 0.430 | 1.45 | 0.827 | 0.765 | |

| * x45 Proper composting can reduce the emission from animal dropping | 0.421 | 0.804 | ||||

| x58 Animal urine is a source of nitrogen gas and emitting/adding N to the environment | 0.538 | 0.840 | ||||

| 20 | x17 Deforestation is responsible for CC | 0.606 | 1.16 | 0.764 | - | |

| 22 | * x44 Livestock (ruminant) are greatly emitting GHG | 0.3848 | 1.01 | 0.783 | ||

| II (Sustainable Adaptation to Agricultural CC) | 2 | x90 CC may be the reason for the increased cost of cultivation | 0.505 | 5.97 | 0.806 | 0.939 |

| ** x91 CC is the reason for the early maturity/harvesting of crops | 0.481 | 0.775 | ||||

| ** x92 Change in planting time is a mitigation measure to CC | 0.442 | 0.760 | ||||

| x94 CC has influenced the increased occurrence of disease attacks in the crop | 0.527 | 0.865 | ||||

| x102 Change from long-duration to short-duration crop varieties is an adaptation strategy to CC | 0.725 | 0.883 | ||||

| x103 Change to more cash crops is an adaptation strategy to CC | 0.711 | 0.876 | ||||

| x104 Change of planting/sowing time as per weather conditions is an adaptation strategy to CC | 0.790 | 0.855 | ||||

| x105 Integrated water management for scarcity (during the winter) is an adaptation strategy to CC | 0.650 | 0.880 | ||||

| x106 Intercropping is an adaptation strategy to CC | 0.708 | 0.847 | ||||

| x107 Construction of farm ponds is an adaptation strategy to CC | 0.531 | 0.737 | ||||

| x108 Mulching is an adaptation strategy to CC | 0.606 | 0.840 | ||||

| * x109 Resort to terrace/settled cultivation in place of shifting cultivation is an adaptation strategy to CC | 0.401 | 0.767 | ||||

| III (Effect of CC on Agriculture) | 4 | x7 CC is mostly anthropogenic | 0.529 | 4.61 | 0.764 | 0.937 |

| ** x77 Occurrence of strong wind has increased | 0.484 | 0.814 | ||||

| * x93 CC has influenced the increased occurrence of insect attacks in the crop | 0.416 | 0.846 | ||||

| x96 (Due to CC) Increased occurrence of incidence of disease in animals | 0.698 | 0.822 | ||||

| x97 (Due to CC) Increased mortality rate of the animals | 0.731 | 0.850 | ||||

| x98 CC is the reason for the reduction in the species of forest trees | 0.665 | 0.910 | ||||

| x99 High temperature is the reason for the reduction in milk production of animal | 0.773 | 0.878 | ||||

| x100 High temperature is the reason for the restricted growth of livestock | 0.675 | 0.851 | ||||

| x101 Collection of water for livestock during summer/drought is a difficult task | 0.665 | 0.860 | ||||

| 6 | x86 Agricultural losses have increased due to CC | 0.704 | 2.69 | 0.899 | 0.930 | |

| x87 CC has influenced the reduction of yield | 0.654 | 0.896 | ||||

| x88 Unfavorable weather is responsible for crop failure | 0.613 | 0.856 | ||||

| x89 CC is a tremendous threat to food security | 0.665 | 0.854 | ||||

| x95 Owing to CC (drought/flood), the availability of fodder for livestock has decreased | 0.502 | 0.808 | ||||

| IV (Impact of CC Or Occurrences of CC consequences) | 3 | x73 CC has a substantial negative impact on cold-loving (temperate) crops (like apples) | 0.533 | 4.84 | 0.880 | 0.939 |

| x79 Occurrence of natural disasters has increased | 0.569 | 0.890 | ||||

| x80 Occurrence of the landslide has increased | 0.785 | 0.896 | ||||

| x81 Occurrence of thunderstorms has increased | 0.709 | 0.857 | ||||

| x82 Phenomenon of drought occurrence has increased | 0.621 | 0.888 | ||||

| x83 Phenomenon of flood occurrence has increased | 0.765 | 0.883 | ||||

| x84 Phenomenon of cyclone occurrence has increased | 0.649 | 0.880 | ||||

| ** x85 Frequency of dry spells has increased | 0.459 | 0.828 | ||||

| * x51 Rice cultivation is emitting CH4 gas | 0.378 | 0.790 | ||||

| 8 | * x1 CC is a natural process | 0.404 | 2.21 | 0.721 | 0.893 | |

| x3 CC is also a reason for global warming | 0.598 | 0.829 | ||||

| x4 CC is the reason for the rise of sea level | 0.848 | 0.850 | ||||

| x5 CC is the reason for mountain glacier melting | 0.819 | 0.930 | ||||

| x6 CC is the reason for pole glacier melting | 0.775 | 0.879 | ||||

| 11 | * x36 Unpredictable occurrence of rainfall has increased | 0.417 | 1.83 | 0.773 | 0.916 | |

| x38 Unpredictable onset of monsoon rain | 0.790 | 0.930 | ||||

| x39 Unpredictable cessation of monsoon rain | 0.741 | 0.870 | ||||

| 19 | x35 The Frequency of heavy rain has increased | 0.648 | 1.23 | 0.785 | - | |

| V (Basic/general awareness/knowledge of CC) | 5 | ** x12 Burning of fuel by vehicle is adding GHGs (and harmful gases) to the environment | 0.408 | 3.04 | 0.833 | 0.892 |

| ** x13 Modernization of society, i.e., better civilization, is also a reason for CC | 0.460 | 0.834 | ||||

| x18 Have you heard about GHGs? | 0.533 | 0.752 | ||||

| x19 Emission of GHGs is the reason for CC | 0.651 | 0.839 | ||||

| x20 CO2 is a GHG | 0.813 | 0.836 | ||||

| x21 CH4 is a GHG | 0.868 | 0.895 | ||||

| x22 N2O is a GHG | 0.803 | 0.840 | ||||

| x23 CFC is also a GHG | 0.504 | 0.803 | ||||

| 7 | x26 Rainfall is a climatic factor/variable | 0.800 | 2.53 | 0.861 | 0.889 | |

| x27 Temperature is a climatic factor/variable | 0.759 | 0.862 | ||||

| x28 Humidity is a climatic factor/variable | 0.730 | 0.850 | ||||

| ** x32 Temperature is rising during the daytime | 0.482 | 0.854 | ||||

| 9 | x8 Overpopulation is also a reason for CC | 0.785 | 2.05 | 0.850 | 0.844 | |

| x9 Urbanisation is a driver for CC | 0.788 | 0.900 | ||||

| ** x10 Generation/production of electricity is a reason for CC | 0.474 | 0.793 | ||||

| x11 Fossil fuel burning is a major driver for CC | 0.560 | 0.821 | ||||

| * x49 Jhum (shifting cultivation) is a reason for CC | 0.403 | 0.750 | ||||

| 16 | x29 Have you ever heard the term CC (CC) | 0.577 | 1.38 | 0.874 | 0.897 | |

| x30 Have you ever heard the term global warming | 0.592 | 0.876 | ||||

| x31 Have you heard about ozone layer depletion | 0.511 | 0.870 | ||||

| * x47 Crop residue burning is adding GHGs | 0.3571 | 0.830 | ||||

| 17 | ** x15 Industry is a responsible driver for CC | 0.479 | 1.33 | 0.802 | 0.693 | |

| x16 Construction (road and building) work is a driver for CC | 0.626 | 0.729 | ||||

| VI (Impact of CC on life and livelihood) | 10 | x69 CC has a huge negative impact on human well-being | 0.731 | 1.90 | 0.827 | 0.908 |

| x70 CC has a huge negative impact on human health | 0.557 | 0.838 | ||||

| x71 CC has a substantial negative impact on livelihood | 0.639 | 0.877 | ||||

| ** x72 CC has a substantial negative impact on livestock | 0.460 | 0.847 | ||||

| 12 | * x25 H2O-vapour is also a reason for local-level warming | 0.434 | 1.72 | 0.740 | 0.805 | |

| * x48 Household (including kitchen waste) waste is also releasing/emitting GHGs | 0.447 | 0.788 | ||||

| x74 Owing to CC (warming), the cold place is more comfortable to live | 0.534 | 0.764 | ||||

| x75 Owing to CC (warming), warm places (tropical zone) are more uncomfortable to live | 0.705 | 0.823 | ||||

| x76 Owing to CC (warming), coastal zones are more vulnerable to sea level rise | 0.550 | 0.814 | ||||

| 18 | x24 CO2 is harmful to the human and mammal kingdom | 0.679 | 1.25 | 0.853 | - | |

| 21 | x2 Owing to increasing population, some extent of CC is unavoidable | 0.761 | 1.14 | 0.832 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Patra, N.K.; Jamir, L.A.; Pathak, T.B. Comprehensive Tool for Assessing Farmers’ Knowledge and Perception of Climate Change and Sustainable Adaptation: Evidence from Himalayan Mountain Region. Climate 2026, 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010020

Patra NK, Jamir LA, Pathak TB. Comprehensive Tool for Assessing Farmers’ Knowledge and Perception of Climate Change and Sustainable Adaptation: Evidence from Himalayan Mountain Region. Climate. 2026; 14(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010020

Chicago/Turabian StylePatra, Nirmal Kumar, Limasangla A. Jamir, and Tapan B. Pathak. 2026. "Comprehensive Tool for Assessing Farmers’ Knowledge and Perception of Climate Change and Sustainable Adaptation: Evidence from Himalayan Mountain Region" Climate 14, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010020

APA StylePatra, N. K., Jamir, L. A., & Pathak, T. B. (2026). Comprehensive Tool for Assessing Farmers’ Knowledge and Perception of Climate Change and Sustainable Adaptation: Evidence from Himalayan Mountain Region. Climate, 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010020