Bridging Economic Development and Environmental Protection: Decomposition of CO2 Emissions in a Romanian Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Methodology and Data

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. CO2 Emissions

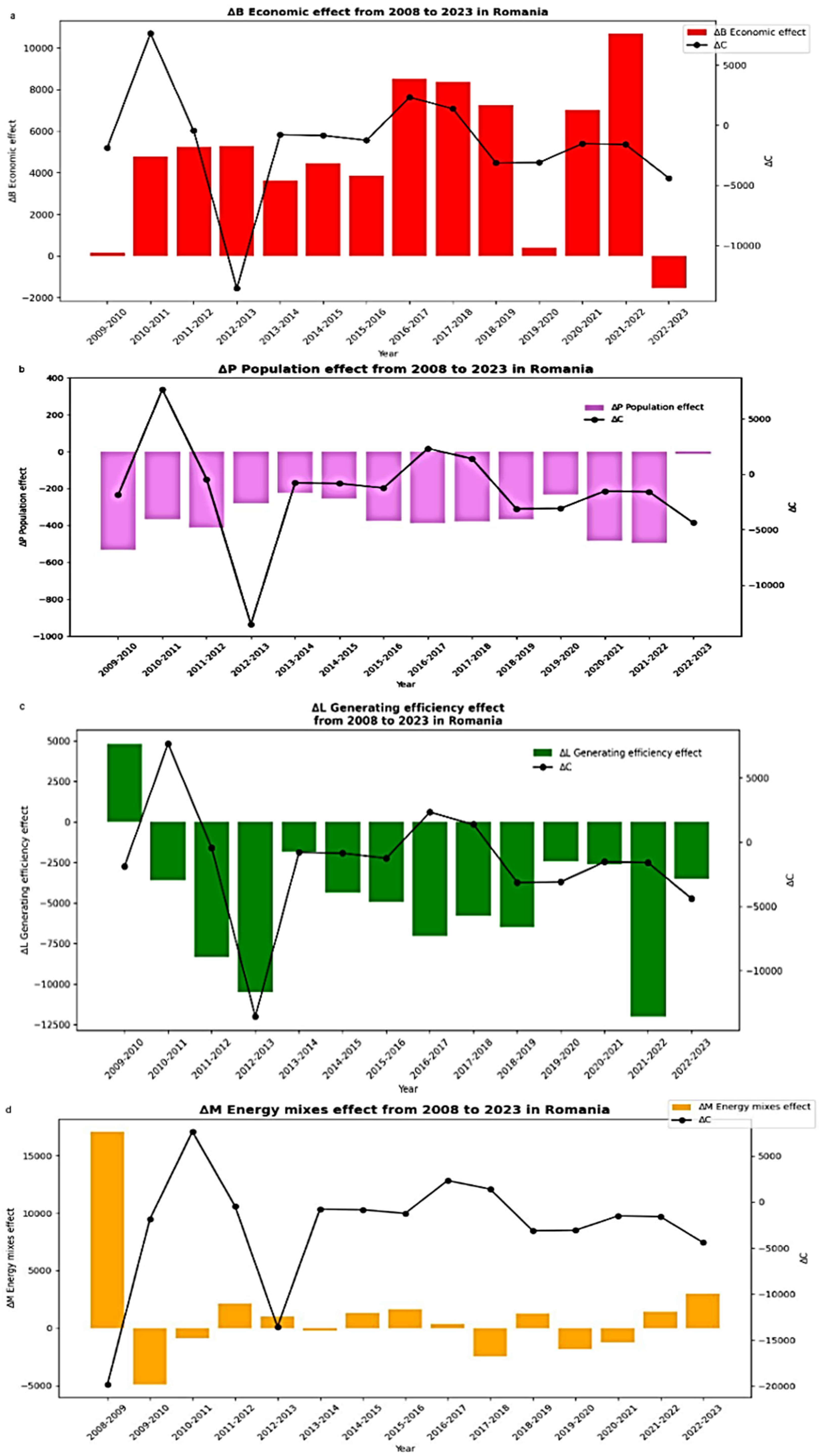

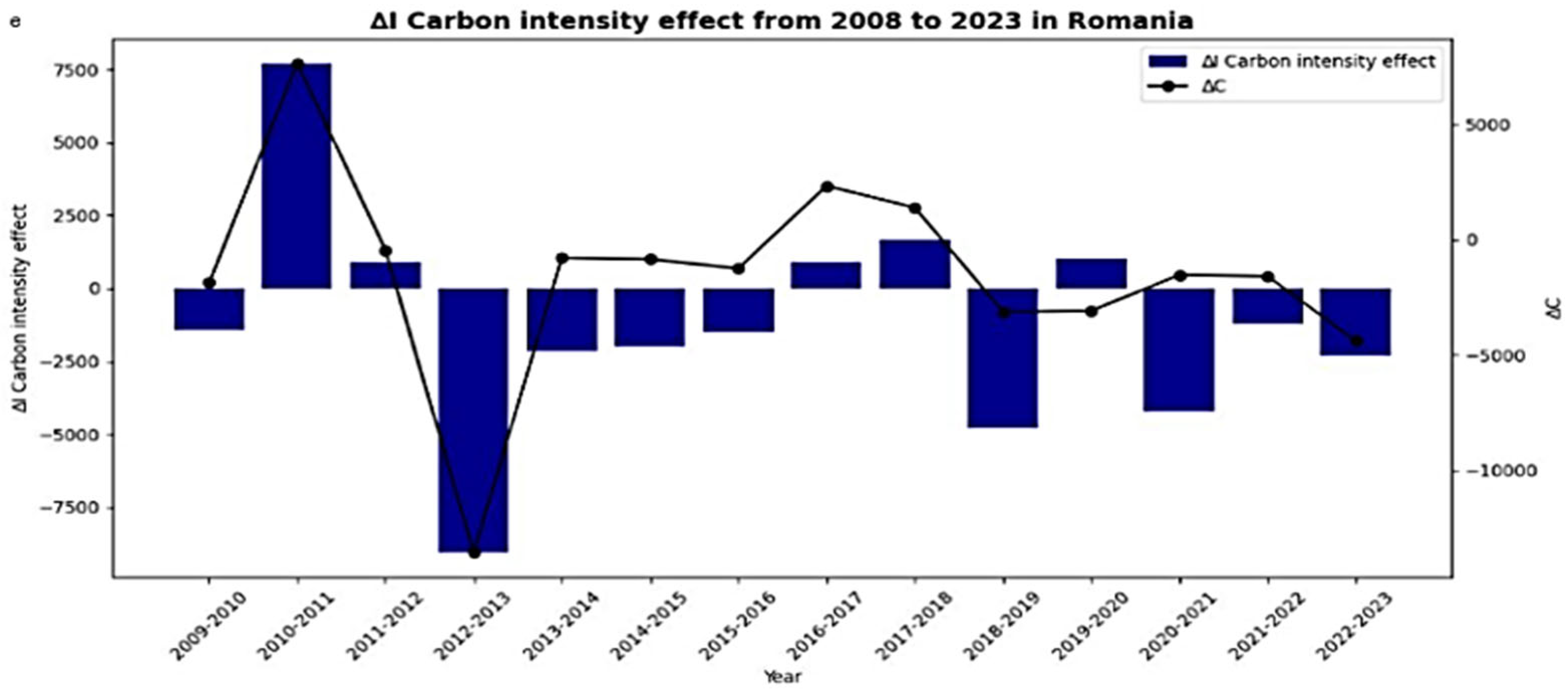

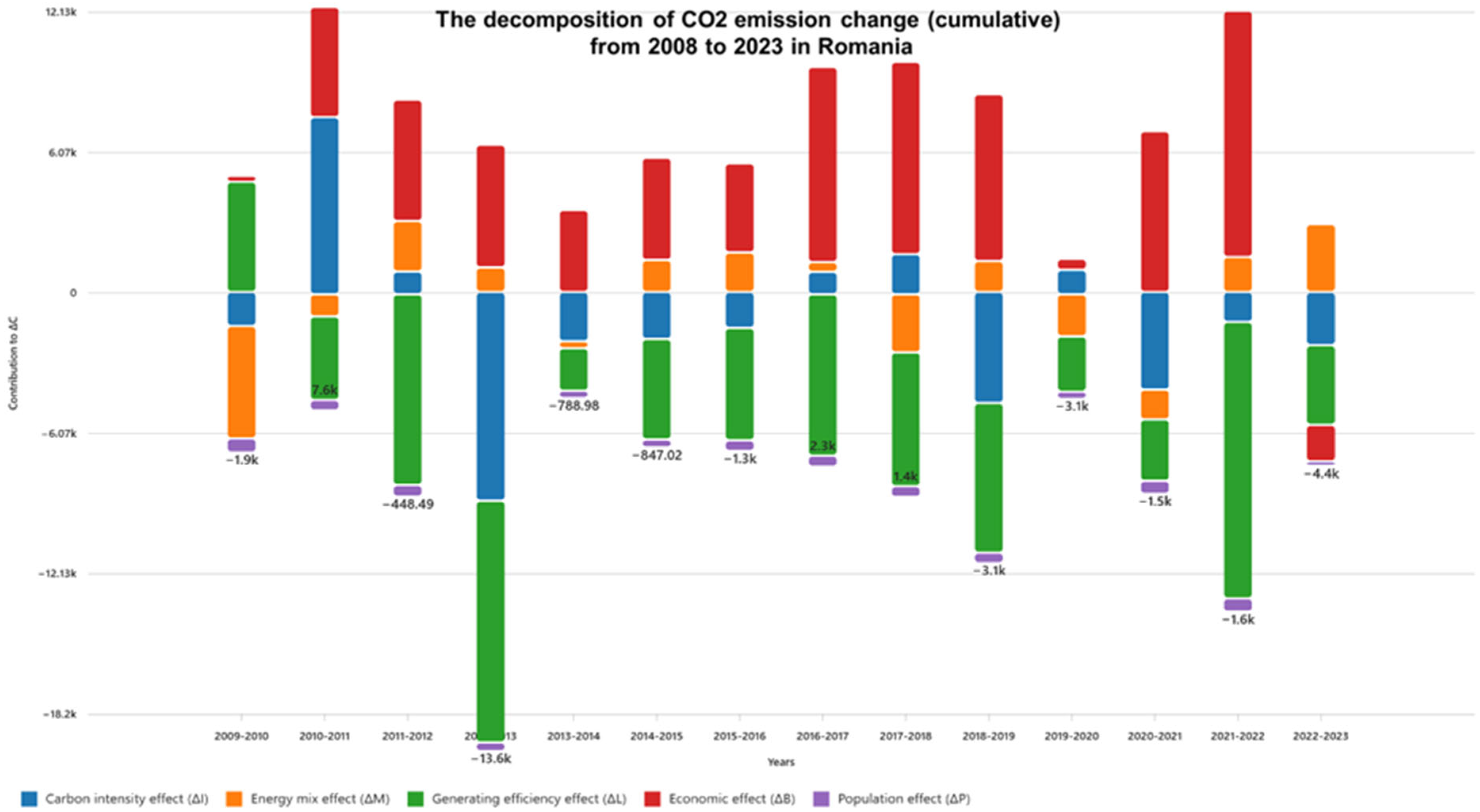

4.2. Contributing Indexes

5. Policy Implications, Limitations, and Recommendations

Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EEA. Annual European Union Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990–2021 and Inventory Report 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/annual-european-union-greenhouse-gas-2 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Paris Agreement. OJ L 282, 19.10.2016, p. 4. 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:22016A1019(01) (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- EC. European Green Deal: Research & Innovation Call; Directorate-General for Research and Innovation; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; ISBN 978-92-76-42387-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yang, X.; Tian, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, T. Decomposition analysis of CO2 emissions of electricity and carbon-reduction policy implication: A study of a province in China based on the logarithmic mean Divisia index method. Clean Energy 2023, 7, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Exploring the impact of transition in energy mix on the CO2 emissions from China’s power generation sector based on IDA and SDA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 30858–30872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.W.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, M. Using LMDI method to analyze transport sector CO2 emissions in China. Energy 2011, 36, 5909–5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.; Casler, S. Input-output structural decomposition analysis: A critical appraisal. Econ. Syst. Res. 1996, 8, 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth, R.B.; Schipper, L.; Duerr, P.A.; Strom, S. Manufacturing energy use in eight OECD countries. Energy Econ. 1991, 13, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, M.A.; Ingebritsen, S.E.; Janik, C.J.; Kauahikaua, J.P. Use of precipitation and ground water isotopes to interpret regional hydrology on a tropical volcanic island: Kilauea Volcano area, Hawaii. Water Resour. Res. 1996, 32, 3525–3537. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, R.M.; Timilsina, G.R. Factors affecting CO2 intensity of power sector in Asia: A divisia decomposition analysis. Energy Econ. 1996, 18, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Decoupling China’s carbon emissions increase from economic growth: An economic analysis and policy implications. World Dev. 2000, 28, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, B.W.; Liu, N. Handling zero values in the logarithmic mean Divisia index decomposition approach. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Bhattacharya, R.N. CO2 emissions from energy use in India: A decomposition analysis. Energy Policy 2004, 32, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenhof, P.A. Decomposition of electricity demand in China’s industrial sector. Energy Econ. 2006, 28, 370–384. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, L.; Ran, Q.Y.; Wu, H.T. A LMDI decomposition analysis of carbon dioxide emissions from the electric power sector in Northwest China. Nat. Resour. Model. 2020, 33, e12284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmann, U.; Wood, R.; Lenzen, M.; Schaeffer, R. Structural decomposition of energy use in Brazil from 1970 to 1996. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R. Structural decomposition analysis of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 4943–4948. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. LMDI Decomposition Analysis of Energy Consumption in the Korean Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability 2017, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira-De Jesus, P.M. Effect of generation capacity factors on carbon emission intensity of electricity in Latin America & the Caribbean—A temporal IDA-LMDI analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 516–526. [Google Scholar]

- İpek Tunç, G.; Türüt-Aşık, S.; Akbostancı, E. A decomposition analysis of CO2 emissions from energy use: Turkish case. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 4689–4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, J.V.; Avram, S.; Băncescu, I.; Gâf Deac, I.I.G.; Gheorghe, C. Evolution of Romania’s economic structure and environment degradation—An assessment through LMDI decomposition approach. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 3505–3521. [Google Scholar]

- Năstase, G.; Șerban, A.; Năstase, A.F.; Dragomir, G.; Brezeanu, A.I. Air quality, primary air pollutants and ambient concentrations inventory for Romania. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 184, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Suo, R.; Han, Q. A study on natural gas consumption forecasting in China using the LMDI-PSO-LSTM model: Factor decomposition and scenario analysis. Energy 2024, 292, 130435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, Z. Improving urban ecological welfare performance: An ST-LMDI approach to the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Land 2024, 13, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Lei, Y.; Wu, S.; Cui, Y.; Dong, Z.; Ren, C. Synergistic emission reductions and health effects of energy transitions under carbon neutrality target. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyab, H.; Saberi-Kamarposhti, M.; Hashim, H.; Yusuf, M. Carbon dynamics in agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and removals: A comprehensive review. Carbon Lett. 2024, 34, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrei, M.; Vintilă, G.; Dascalu, E.D.; Roman, A.; Firtescu, B.N. The Impact of Environmental Tax Reform on Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Empirical Evidence from European Countries. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2017, 16, 2843–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Gill, A.R.; Ghosal, K.; Al-Dalahmeh, M.; Alsafadi, K.; Szabó, S.; Harsanyi, E. Assessment of the environmental Kuznets curve within EU-27: Steps toward environmental sustainability (1990–2019). Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 2024, 18, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firtescu, B.N.; Brinza, F.; Grosu, M.; Doaca, E.M.; Siriteanu, A.A. The effects of energy taxes level on greenhouse gas emissions in the environmental policy measures framework. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 965841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ou, X.; Zhang, X. Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index decomposition of CO2 emissions from urban passenger transport: An empirical study of global cities from 1960–2001. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, B.W. The LMDI approach to decomposition analysis: A practical guide. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y. Impact of Carbon Dioxide Emission on GNP Growth: Interpretation of Proposed Scenarios; IPCC Energy and Industry Subgroup: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- NISR. National Institute of Statistics Romania, 2024. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Li, K. Influencing Factors and Emission Reduction Paths of Industrial Carbon Emissions Under Target of “Carbon Peaking”: Evidence from China. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2025, 34, 2715–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, V.; Cascetta, F.; Nardini, S. Analysis of the carbon emissions trend in European Union—A decomposition and decoupling approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Raza, N.; Sun, D.; Akmal, M.; Nayab, F. Energy and social factor decomposition to identify drivers impeding sustainable environmental transition in emerging countries: SDGs-2030 progress assessment using LMDI analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 24599–24618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, E.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Sun, S.; Wang, S. Factors Influencing Energy Consumption from China’s Tourist Attractions: A Structural Decomposition Analysis with LMDI and K-Means Clustering. Environ. Model. Assess. 2024, 29, 569–587. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Li, R.; Sun, J. Does artificial intelligence promote energy transition and curb carbon emissions? The role of trade openness. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Term | Definition and Formula | Units | Effect Name and Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Carbon Emissions | Total CO2 emissions from fuel combustion | Gg tons CO2/year | Dependent variable |

| F | Fossil Energy | Total fossil energy resources | ktoe | – |

| E | Total Energy | Total energy consumption before transformation | ktoe | – |

| P | Population | Total population | Persons | ΔP → Population effect |

| G | GDP | Gross Domestic Product (constant currency) | RON million | ΔB → Economic effect |

| C/F | Carbon Intensity | CO2 emissions per unit of fossil energy | MtCO2/ktoe | ΔI → Carbon intensity effect |

| F/E | Energy Mix | Share of fossil energy in total energy | % | ΔM → Energy mix effect |

| E/G | Energy Efficiency | Energy use per unit of GDP | ktoe/RON million | ΔL → Energy efficiency effect |

| G/P | GDP per Capita | GDP divided by population | RON/person | ΔB → Economic effect |

| ΔC | Change in Emissions | Ct–C0 (difference between year t and base year) | MtCO2 | Total change |

| ΔI, ΔM, ΔL, ΔB, ΔP | Decomposition Effects | Contributions of each factor to ΔC | MtCO2 | Interpret as drivers of change |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dragomir Bălănică, C.M.; Sirbu, C.G.; Ioan, G.; Pirju, I.S. Bridging Economic Development and Environmental Protection: Decomposition of CO2 Emissions in a Romanian Context. Climate 2026, 14, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010010

Dragomir Bălănică CM, Sirbu CG, Ioan G, Pirju IS. Bridging Economic Development and Environmental Protection: Decomposition of CO2 Emissions in a Romanian Context. Climate. 2026; 14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleDragomir Bălănică, Carmelia Mariana, Carmen Gabriela Sirbu, Gina Ioan, and Ionel Sergiu Pirju. 2026. "Bridging Economic Development and Environmental Protection: Decomposition of CO2 Emissions in a Romanian Context" Climate 14, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010010

APA StyleDragomir Bălănică, C. M., Sirbu, C. G., Ioan, G., & Pirju, I. S. (2026). Bridging Economic Development and Environmental Protection: Decomposition of CO2 Emissions in a Romanian Context. Climate, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010010