Abstract

Agricultural financing is crucial for economic development and sustainability. However, little is known about how bankers’ concerns about climate change influence their decision-making for agricultural financing and development and how these concerns are related to possible future performance. This study investigates a research question “how do bankers’ climate concerns and value orientation influence agricultural financing and development?” and the hypotheses “bankers’ climate concerns are negatively related to agricultural financing and development, whereas their value orientation for future generations is positively associated with these endeavors”. We conduct questionnaire surveys and collect data on climate concerns, prosocial attitude for future generations and sociodemographic & bank related information from 596 bankers at three areas in Bangladesh. The results reveal three main findings. First, bankers who have high levels of climate concerns tend to be less optimistic about agricultural financing and development. Second, bankers who live in high climate-change areas tend to have more severe climate concerns and darker prospectives in agricultural financing and development than those in low climate-change areas. Third, bankers who have a high value orientation for future generations are likely to be positive about future agricultural financing and development. Overall, our findings suggest that future agricultural financing and development shall be discouraged as climate change becomes severe, hitting low-land areas, such as Bangladesh, through the lens of bankers’ perceptions, unless the bankers possess high concerns for future generations. To counter such negative possibilities, a new agricultural financing scheme, such as “agricultural green banking”, shall be necessary to implement.

1. Introduction

Agriculture and climate are crucial to human existence; however, ongoing environmental and climate change challenges pose significant threats to ensuring global food security in the 21st century [1]. The effects of climate change are particularly evident in the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, which have far-reaching consequences for both natural ecosystems and human life [2,3]. The year 2023 set new records for the highest temperature ever recorded on a warming planet, with extreme floods, storms, droughts, wildfires and outbreaks of pests and diseases increasingly dominating global headlines [4]. As a low-lying country, Bangladesh is particularly vulnerable to rising temperatures, floods, droughts, salinity, cyclones and sea level changes caused by climate change, creating severe risks for agricultural development and economic stability [5,6,7]. In this context, banking institutions can play a significant role by supporting diverse eco-friendly strategies that promote both agricultural and economic sustainability [8,9]. To ensure sustainability, it is crucial to understand employees’ perceptions and cognitions, their consciousness of environmental & climate change issues and their attitudes toward future generations in banking operations [10,11,12]. Therefore, this study examines the concerns of bankers, as decision-makers in agricultural financing and development, regarding climate change and future generations and how these concerns and value orientation are related to possible future performance.

Numerous studies document that current investments and commitments are vastly inadequate to meet the necessary requirements for sustaining agriculture under climate change, particularly in developing countries [13,14]. According to a climate change report in 2013, the banking industry is the lowest-ranked industry in climate change performance [15]. Moreover, banks in Asia receive the lowest scores of any region across all categories of climate change strategies and actions [8]. A global assessment by the World Bank reveals that insufficient investment in agriculture has significantly contributed to the decline in agricultural productivity since the 1980s, and this sector is expected to encounter even greater challenges in the future due to climate change [16]. It is also evident that banks and other financial institutions are reluctant to finance the agricultural sector because of concerns about low returns and high investment risks associated with climate change [17]. Some studies show that access to agricultural credit plays a crucial role in enhancing farming production and reducing the adverse effects of climate change [18,19,20]. Aiello [21] reports that insufficient financial investments restrict farmers’ capacity to handle and recover from adverse events, ranging from global events to natural disasters. Thus, it is crucial for the banking industry to develop effective strategies and to make investments that address the impacts of climate change and help mitigate its effects.

Bangladesh is recognized as a leading emerging economy that offers significant investment opportunities and economic growth prospects, positioning it to play a major role in the 21st century [22]. As a developing and agriculture-based country, Bangladesh remains highly susceptible to the impacts of climate change, which pose serious threats to food security and limit prospects for sustainable economic development [23]. The banking sector is essential for climate change adaptation, enhancing food security and supporting economic development; however, insufficient access to credit facilities, limited banking operations, biased selection of target areas and inappropriate credit disbursement continue to undermine the effectiveness of banking systems in Bangladesh [24,25]. Alauddin and Biswas [24] document that the agricultural credit scenario, particularly institutional credit coverage, needs improvement to ensure that farmers receive adequate credit for timely production. In the banking industry, managers’ psychological behaviors play a crucial role in long-term credit distribution, collateral setting, credit assessment and loan sanctioning [26]. While previous studies highlight the importance of bankers’ behaviors in promoting economic and environmental sustainability, it remains unclear how their attitudinal orientations influence possible future performance in the banking sector. Therefore, this study examines how bankers’ attitudes and value orientation could impact future agricultural financing and development.

Past studies reveal that employees’ climate concerns, especially at the top management level, are linked to organizational decision-making, actions and financial performance [27,28,29,30,31]. For example, Buranatrakul and Swierczek [8] find that directors and bank executives from North America, Europe and Australia are more proactive in incorporating climate change initiatives into decision-making and risk management due to their heightened concerns about climate change and environmental awareness; however, strategic actions vary across regions. Kartadjumena and Rodgers [32] document that sustainability concerns, such as environmental and climate change issues, have significant effects on the financial health and market performance of banking companies. A group of studies suggests that people’s value orientation for future generations motivates proenvironmental actions, supports environmental policies and influences financial performance [33,34,35,36]. For example, Syropoulos and Markowitz [37] identify a correlation between perceived responsibility for future generations and decision-making as well as prosocial behaviors within an intergenerational context. Syropoulos and Markowitz [12] find that those who feel a strong sense of responsibility for future generations are more likely to take significant measures to address climate change and protect the environment. Therefore, climate concerns and value orientation for future generations are powerful factors in understanding decision-making processes and actions aimed at addressing various environmental and financial issues.

A growing body of research highlights the importance of people’s concerns about climate change and future generations in decision-making, proenvironmental behaviors and economic performance [38,39,40,41,42]. However, there is still a limited understanding of how employee’s concerns about climate change and future generations influence their decisions and potential future performance, particularly in the financial sector. In this paper, we seek to address these issues by exploring the question “how do bankers’ climate concerns and value orientation influence agricultural financing and development”? To this end, we conduct questionnaire surveys and collect data on climate concerns, prosocial attitude for future generations and sociodemographic & bank related information from 596 bankers at three areas in Bangladesh. The aim of this study is to understand how bankers’ climate concerns and value orientation influence agricultural financing and development and to explore potential solutions for improving agricultural financing through the development of new loan designs and risk assessment strategies within banking policies.

1.1. Agriculture and Banking System in Bangladesh

Agriculture plays a crucial role in the overall economic performance of Bangladesh, employing a large share of the labor force, generating substantial foreign exchange earnings, supplying food nationwide and making a significant contribution to the gross domestic product (GDP) [43,44]. To promote agricultural development and strengthen the national economy, agricultural financing is indispensable, and the involvement of formal banking institutions plays a pivotal role in achieving these goals [45]. The Bangladesh Bank (BB), the central regulatory authority, supervises the banking systems and regulates all scheduled banks, such as nationalized commercial banks, privately owned commercial banks, foreign commercial banks and specialized banks that provide essential financial services to farmers [46,47]. According to agricultural credit policy, all these banks must disburse at least 2% of their total loans as agricultural credit, offering short-term loans for seasonal farming, intermediate-term loans for equipment and infrastructure and long-term loans for larger projects such as land development and the establishment of agro-based industries [48,49]. In line with the country’s development agenda, BB formulates the “agricultural and rural credit policy” each year to ensure that funds are allocated and distributed effectively, efficiently and promptly to agricultural and rural sectors, benefiting farmers at the grassroots level [49]. The amount of agricultural credit is increasing every year, but it is insufficient to meet the enormous demand generated by farmers [50]. Moreover, the credit disbursement, oversight and monitoring services from lender banks, such as nationalized and other commercial banks, are still inadequate for advancing the agricultural sector in Bangladesh [45].

1.2. Theoretical Perspective and Hypothesis Development

Social cognitive theory suggests that both cognitive and environmental factors play critical roles in decision-making [51,52]. For example, financial institutions consider environmental challenges, such as climate change and ecological balance, to promote sustainable development [23]. Teo et al. [53] report that individuals with heightened climate concerns tend to hold a more negative outlook about the future. The value-belief-norm theory postulates that human values, concerns, beliefs and personal norms are influencial in shaping proenvironmental actions and behaviors [54,55,56]. For example, concerns about climate change can help explain and predict risk perception as well as future decision-making [57]. Brügger et al. [58] highlight that understanding how experiences of climate change shape motivation to act is crucial for predicting future decision-making and formulating effective responses to climate-related challenges. The value-orientation theory suggests that people’s decisions and behaviors are guided by their values related to different times, relationships, natures and motives [59,60]. This study focuses on a psychological factor, the future-oriented attitude of managers, which influences their decision-making in banking performance. For example, a future-oriented attitude is a prosocial attitude for future generations that reflects concern for both current and upcoming generations and guide individuals in making long-term and forward-looking decisions [61]. Based on the above theories, we develop the following hypotheses: “bankers’ climate concerns are negatively related to agricultural financing and development, whereas their value orientation for future generations is positively associated with these endeavors”.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area, Sample and Sampling Strategy

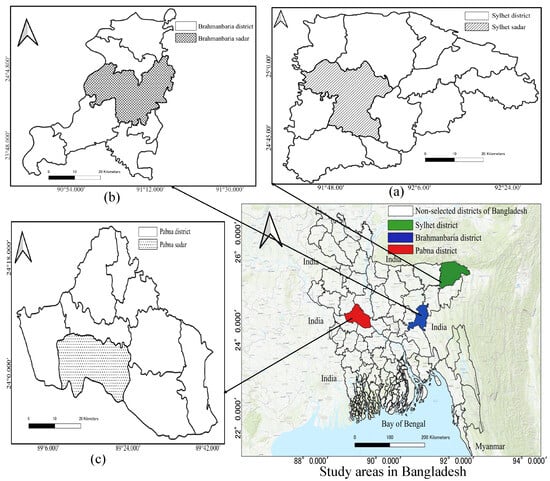

A cross-sectional design was applied to collect necessary data from bankers via a predefined questionnaire in three districts, namely, Sylhet, Brahmanbaria and Pabna, which belong to the Sylhet, Chittagong and Rajshahi divisions, respectively, in Bangladesh between April 2024 and May 2024. Figure 1 represents the location of the study areas (districts) in Bangladesh. Bangladesh has long been exposed to a range of hazards, including climatological hazards such as droughts and sea-level rise; hydrometeorological hazards such as floods and cyclones; and geophysical hazards such as landslides and erosion [62]. The districts of Sylhet and Brahmanbaria are located in the eastern part, whereas Pabna is located in the northwestern part of Bangladesh, and all three districts are highly vulnerable to heavy rainfall and flooding during the monsoon and premonsoon seasons according to the climate vulnerability index. Moreover, the Brahmanbaria district is additionally vulnerable to threats from climate change, such as cyclone hazard and flash flood, as indicated by various indices [62]. The Pabna district is further vulnerable to both surface and ground water droughts and erosion risk [63]. Compared to these two districts, Sylhet is less vulnerable to cyclone hazards, erosion and drought indices [62,63]. Considering the different climatic conditions, we classify the Sylhet district as a low climate-change area, whereas Brahmanbaria is considered a high hazard-prone area, and Pabna is regarded as a high drought-prone area. The total agricultural credit provided by banks in Bangladesh is 26.03%, whereas the figures are 32.48%, 31.32% and 20.06% in the Sylhet, Chittagong and Rajshahi divisions, respectively, indicating that the studied areas reflect the national profile of banking practices in Bangladesh [64]. Collectively, these three regions encompass 42% of all bank branches in Bangladesh [65].

Figure 1.

The locations of the study areas (districts) in Bangladesh: (a) Sylhet (low-climate change area), (b) Brahmanbaria (high hazard-prone area) and (c) Pabna (high drought-prone area). The map also shows the locations of the subdistricts in the selected districts.

To perform random sampling, we collected lists of all banks with their branches in each selected area. We then randomly identified the selected number of bankers, mainly bank managers, by using the list and a random number generator from each area. The current study randomly identified 596 bankers, more specifically, 181 from a low climate-change area, 166 from a high hazard-prone area and 249 from a high drought-prone area. A sample size of 500 or more is generally sufficient to produce statistics that accurately reflect the parameters of the targeted population [66]. A post hoc power analysis with a significance level of 0.05, a total sample size of 596 and a medium effect size indicates that the study achieved 99% power, suggesting a strong ability to detect the anticipated effects and ensure the robustness and reliability of the results. Several pilot surveys were conducted prior to the main survey to ensure that bankers did not encounter any difficulties in responding to the questionnaire items. The second author was the chief administrator of this survey and provided training to the research assistants about data collection and conducting the surveys. Trained research assistants contacted each bank and collected necessary information from bankers through face-to-face interviews. All bankers willingly participated in this survey and presented signed written consent before providing data. The survey process included a detailed account of ethical clearance, anonymization procedures and data quality control to maintain the integrity and ethical standards of the study.

2.2. Key Variables

Table 1 provides an overview of the key dependent and independent variables along with their definitions. A baseline questionnaire survey was conducted to gather information on bankers’ future agricultural financing and development, their climate concerns, prosocial attitude for future generations and sociodemographic & bank characteristics. This paper uses bankers’ future agricultural financing (FAF) and future agricultural development (FAD) as dependent variables. Each banker is asked to provide their perception regarding FAF, stating “How do you perceive that agricultural financing will be profitable from now to the next 30 years?” and the evaluations are provided on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Likewise, to understand bankers’ perceptions related to FAD, we pose the following question: “How do you perceive that agriculture in Bangladesh will develop from now to the next 30 years?” and the responses are recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Later, we categorize bankers’ responses into two groups for each question. If bankers do not disagree about FAF (FAD), we assign a value of 1; otherwise, it is 0.

Table 1.

Definitions of the variables.

To assess banker’s climate concerns, we collect data on temperature and sunlight, precipitation, seasonality and topography factors by asking, “How much consideration do you allocate to each climate factor when providing loans to farmers?” and the responses are recorded on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (no concern) to 5 (high concern). To incorporate practical experiences of climate change, we include three different climate-change areas: low climate-change, high hazard-prone and high drought-prone areas. The prosocial attitude for future generations is measured via a social generativity scale (see, e.g., [67,68]). This scale has 6 items, including the following statements: (1) “I carry out activities in order to ensure a better world for future generations”, (2) “I have a personal responsibility to improve the area in which I live”, (3) “I give up part of my daily comforts to foster the development of next generations”, (4) “I think that I am responsible for ensuring a state of well-being for future generations”, (5) “I commit myself to do things that will survive even after I die” and (6) “I help people to improve themselves”. The items are rated from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” on a 5-point Likert scale. The score of prosocial attitude for future generations is calculated by summing the scores for all 6 items. Additional information is collected on sociodemographic & bank related variables, such as age, gender, educational background, bank type, bank collateral system and agricultural loan.

The internal reliability of the prosocial attitude for future generations is relatively low (Cronebach’s = 0.52). According to Nunnally [69], a reliability coefficient of 0.50 or higher may be considered adequate during the early stages of scale development. In this context, the construct of prosocial attitude for future generations is relatively new and has only recently been applied within the banking sector in Bangladesh. Furthermore, Schmitt [70] notes that Cronbach’s alpha should not be the sole criterion for evaluating a scale, especially when the construct being measured is conceptually broad. Given the limited number of items in the scale, Cronbach’s alpha is likely to underestimate internal consistency, as noted by Briggs and Cheek [71], suggesting that the calculation of the mean interitem correlation is another appropriate measure for scales with few items. In this study, the item-total correlations range from 0.22 to 0.32, exceeding the acceptable threshold (>0.20). To assess the scale’s structure, a confirmatory factor analysis is performed, revealing that the factor loadings exceed > 0.30 and are significant at the 1% significance level. According to Field [72], factor loadings below 0.3 should be suppressed to ensure the clarity and interpretability of the factor structure. The model fit test results are as follows: = 18.98, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.04 (acceptable range ), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.03 (acceptable range ), normed fit index (NFI) = 0.90 (acceptable range ) and comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.94 (acceptable range ), indicating good model fit.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Different nonparametric tests, such as chi-squared, Kruskal-Wallis are applied to compare the differences in the key variables among various climate-change areas. This study applies logit regressions to quantitatively identify the influences of bankers’ climate concerns and value orientation for future generations on FAF and FAD. Banker’s FAF and FAD are expressed as binary values 0 or 1. Let s be the dependent variables of FAF and FAD such that if banker i does not disagree about FAF and FAD, respectively, and otherwise. The probability for banker i to positively perceive FAF (FAD), denoted by , is assumed to follow the distribution function F evaluated at , where is a vector of explanatory variables for banker i () and is a vector of parameters (). The distribution function of the logit regression model is as follows:

A specification of Equation (1) enables us to compute via maximum likelihood methods to characterize [73,74,75]. A series of logit regressions are applied step by step to check the robustness of our results. First, the relationships between climate concerns and FAF are examined. Second, the prosocial attitude for future generations and climate-change areas are added. Finally, certain sociodemographic & bank characteristics are included in the model. The same procedure is applied for FAD. Overall, we assess the relationships of climate concerns and value orientation with FAF and FAD by controlling for sociodemographic & bank characteristics through logit regressions. We also estimate ordered probit regressions for FAF and FAD separately, and the results remain consistent with the results of logit regressions (see the ordered probit regression results in Table A1 and Table A2 in Appendix A). However, we present the logit results as the main analysis in the manuscript, as they offer more straightforward interpretations, facilitate clearer evaluation of variable contributions within the model and are more commonly used in applied research for policy-relevant insights [76].

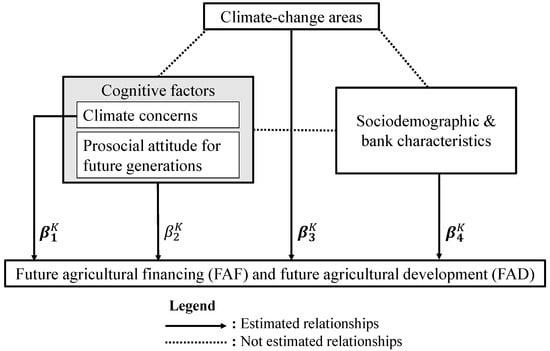

The conceptual framework in Figure 2 illustrates the relationships of cognitive factors such as climate concerns and prosocial attitude for future generations with FAF and FAD, along with certain sociodemographic & bank characteristics in various climate-change areas. The relationships among the variables in Figure 2 represented by solid arrows, are examined in this study, whereas other relationships, shown by dashed arrows, have been documented or tested in other studies [12,38,42,77]. With this framework in mind, we focus on estimating the coefficients of , , and in Figure 2. In this framework, a coefficient of each independent variable is considered to represent the association of that variable with FAF and FAD, respectively, after the effects of all other variables have been netted out. Based on social cognitive, value-belief-norm and value-orientation theories, the conceptual framework in Figure 2 contextualizes the associations to clarify the mechanisms underlying agricultural financing and development, hypothesizing that certain cognitive factors, such as climate concerns and prosocial attitude for future generations matter for future possible performance. The estimated coefficients of and are the key parameters enabling us to address not only the research questions but also the hypotheses. Thus, cognitive factors, including climate concerns and prosocial attitude for future generations, are expected to significantly influence FAF and FAD, even after controlling for sociodemographic & bank characteristics, irrespective of various climate-change areas.

Figure 2.

A conceptual framework describing the relationships of cognitive factors, climate-change areas and sociodemographic & bank characteristics with bankers’ future agricultural financing (FAF) and future agricultural development (FAD), where , , are vectors of coefficients and is a coefficient of corresponding factors; and .

3. Results

Table 2 summarizes the basic statistics of the major independent variables for various climate-change areas and overall bankers in the sample. Bankers residing in high climate-change areas (hazard-prone and drought-prone) are more concerned about temperature and sunlight, precipitation, seasonality and topography than those living in low climate-change areas. The median values of overall bankers’ concerns about temperature and sunlight, precipitation, seasonality and topography are 3, 4, 4 and 4, respectively, indicating a high level of concern about climate change. The average values of bankers’ prosocial attitude for future generations in low climate-change, high hazard-prone and high drought-prone areas are 25.14, 25.16 and 25.73 points, respectively, and these values significantly differ among climate-change areas. The overall average age of bankers is 38 years and the mean age varies according to various climate-change areas. The percentages of male bankers in low climate-change, high hazard-prone and high drought-prone areas are 86%, 96% and 95%, respectively. The educational background of bankers does not vary among climate-change areas, and they have mainly business-related educational background. Most bankers are from private banking institutions, with percentages of 72%, 68% and 64% in low climate-change, high hazard-prone and high drought-prone areas, respectively. The banks follow a fixed-asset collateral system, and the percentages of this system varies according to climate-change areas. The amount of agricutural loan in high drought-prone area (hazard-prone area) is almost eight times (two times) greater than that in low climate-change area. In summary, bankers living in high climate-change areas have greater climate concerns than bankers in low climate-change area do, and all other factors, such as prosocial attitude for future generations and most sociodemographic & bank characteristics, vary among climate-change areas.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of the independent variables by areas.

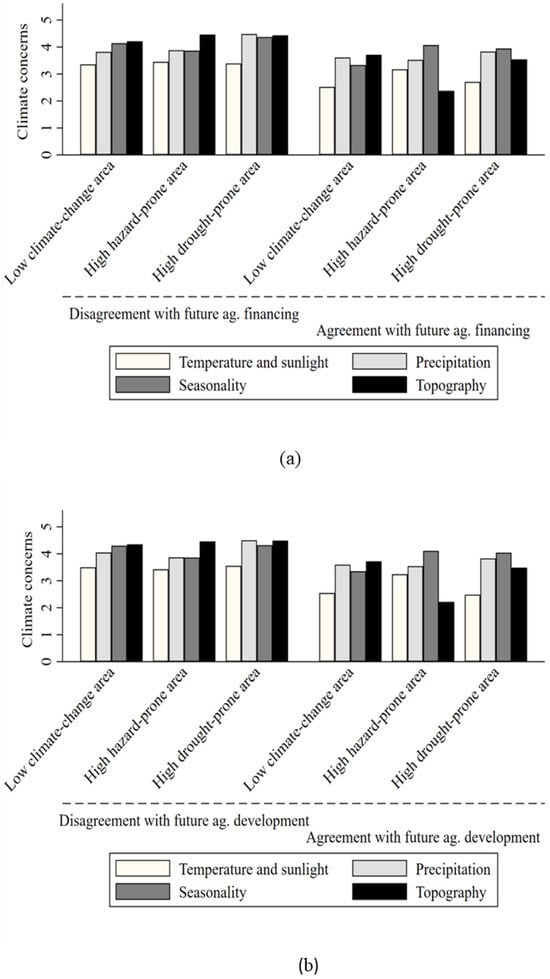

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics, such as the mean, median, standard deviation, minimum and maximum, of the major dependent variables for various climate-change areas and overall bankers in the sample. Major differences are observed in the means of future agricultural financing (FAF) and future agricultural development (FAD) across various climate-change areas: low climate-change, high hazard-prone and high drought-prone. The percentages of bankers who do not disagree with FAF (FAD) are 85%, 24% and 39% (89%, 22% and 40%) in low climate-change, high hazard-prone and high drought-prone areas, respectively. These findings suggest that bankers in low climate-change area have a more positive outlook on FAF and FAD than do those in high hazard-prone and high drought-prone areas. Moreover, in Figure 3, bankers who have high concerns about temperature and sunlight, precipitation, seasonality and topography tend to disagree with the perceptions of FAF and FAD, whereas those with low climate concerns tend to agree with these endeavors across all climate-change areas. In most cases, the level of concern about temperature and sunlight, precipitation, seasonality and topography is greater in high climate-change areas (hazard-prone and drought-prone) than in low climate-change area, regardless of agreement or disagreement regarding FAF and FAD in Figure 3. Overall, bankers living in high climate-change areas and who are highly concerned about climate change tend to be less optimistic about future agricultural financing and development.

Table 3.

Summary statistics of the dependent variable by climate-change areas.

Figure 3.

Bar diagrams of climate concerns in different climate-change areas by (a) future agricultural financing (FAF) and (b) future agricultural development (FAD).

The logit models in Table 4 present the regression results for FAF and FAD, respectively. We apply different regression model specifications to check the robustness of our analyses, and we confirm that the main results in Table 4 remain the same in all models. Models 1-1 and 1-3 (2-1 and 2-3) report the estimated coefficients of the independent variables for FAF (FAD) in the logit models. Models 1-2 and 1-4 (2-2 and 2-4) indicate the estimated marginal effects of each independent variable based on the estimated coefficients in each model, representing a change in the likelihood of bankers’ nondisagreement with FAF (FAD), when the independent variable increases by one unit, with the other factor fixed at the sample mean. Model 1-4 (2-4) is the full model that includes all independent variables for FAF (FAD). We focus mainly on reporting the marginal effects of climate concerns, climate-change areas and prosocial attitude for future generations because they have been identified as remaining significant at the 1% to 10% significance levels in all models. However, the estimations also reveal other significant independent variables, such as the bank collateral system, that significantly influence FAF and FAD. The results suggest that banks with fixed-asset collateral are 43% and 28% less likely to positively perceive FAF and FAD, respectively, than those with no collateral system. One plausible explanation for this difference could be that the banks introduce a collateral system where the loan default rate cases are high.

Table 4.

Regression coefficients and marginal effects of the independent variables for future agricultural financing (FAF) and future agricultural development (FAD) in the logit regressions.

The likelihoods of bankers’ nondisagreement with FAF and FAD decrease by 5% and 9%, respectively, with a one-point increase in their concern about temperature and sunlight. Wit respect to precipitation, a one-point increase in concern leads to a decrease in the probabilities of bankers’ nondisagreement with FAF and FAD by 6% and 8%, respectively. These results suggest that bankers who are greatly concerned with climate change tend to be less optimistic about future agricultural endeavors. Previous studies suggest that fluctuations in temperature, irregular precipitation and overall climate uncertainty pose challenges to financing [78,79]. Similarly, a one-point increase in concern about topography decreases the likelihood of bankers’ nondisagreement with FAF and FAD by 12% and 18%, respectively, suggesting that heightened concern about topography may reflect reduced optimism in this area. The literature indicates that topography directly influences land productivity and farming practices, highlighting its crucial role in agricultural financing [80]. However, we do not find any significant associations of seasonality concern with FAF or FAD. This result may be attributed to the reduced seasonal variation in Bangladesh, where the number of seasons has decreased from six to four [81]. The bankers who live in high hazard-prone and drought-prone areas are 64% and 49% less likely to positively perceive FAF than those who live in low climate-change area. The probabilities of bankers’ nondisagreement with FAD decrease by 73% and 54% for those in high hazard-prone and drought-prone areas compared with those in low climate-change area. This result indicates that bankers who live in high climate-change areas tend to have a darker outlook on agricultural prospects than those who live in low climate-change areas. In terms of value orientation, the probabilities of bankers’ nondisagreement with FAF and FAD increase by 3% and 3%, respectively, with a one-point increase in value orientation for future generations. This result indicates that bankers with a high value orientation for future generations are more likely to have a positive outlook on future agricultural financing and development.

Overall, the summary statistics, tests and diagrams indicate that bankers who reside in areas vulnerable to climate change and who express heightened concern about climate change tend to be less optimistic about FAF and FAD. These future endeavors are characterized by climate concerns, climate-change areas, prosocial attitude for future generations and sociodemographic & bank characteristics as described in the conceptual framework in Figure 2, providing insights for our research question and hypotheses. The regression results show that bankers who have high levels of climate concern tend to be less optimistic about FAF and FAD. Bankers who live in high climate-change areas tend to have more severe climate concerns and more negative perspectives on FAF and FAD than those in low climate-change areas. Moreover, bankers who have a high value orientation for future generations are likely to be positive about FAF and FAD. The results suggest that strengthening bankers’ value orientation for future generations is essential to reducing negative possibilities in agricultural financing and development in the financial sector.

4. Discussion

Environmental issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution and the misuse of natural resources have long-term impacts that necessitate enduring strategies and actions grounded in conscious thinking and planning [82]. The associations among climate concerns, prosocial attitude for future generations and possible future performance can be explained through various theoretical frameworks. Our research reveals that high levels of climate concern and living in high climate-change areas lead to be less optimistic outlook on agricultural financing and development, aligning with the mechanisms proposed by social cognitive and value-belief-norm theories. Prospect theory also helps to explain these associations by suggesting that decisions under uncertainty are driven by the desire to either secure gains or avoid losses [83,84,85,86]. Managers make decisions based on how a problem is framed, which may deviate from economic rationality and instead rely on cognitive processes, leading to potential biases [11,87]. In practice, cognitive biases are consistently present in managers’ strategic decision-making because they often make decisions in complex situations [88,89,90,91]. We argue that managers make decisions under conditions of uncertainty and hence place greater emphasis on potential losses than on gains. In contrast, prosocial attitude for future generations motivates managers to adopt sustainable strategies to improve financial performance in the banking sector, which is consistent with the value-orientation theory. This situation can also be interpreted through stakeholder theory, which posits that a responsible institution, such as a bank, meets societal expectations and promotes environmental values, including sustainability [92,93,94,95]. Normative stakeholder theory asserts that managers bear a moral obligation to acknowledge the interests of particular corporate constituent groups [96,97]. Thus, it is crucial to maintain a sense of responsibilities for the future and future generations through different approaches.

Several future-studies approaches such as visioning, backcasting, scenario planning and future design, have been widely used across different fields, demonstrating how individuals’ and organizations’ prospective thinking and experiences related to the future and future generations influence their strategies and decision-making [98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105]. Studies suggest that some future-studies approaches, such as scenario planning, foresighting, backcasting and future design, can improve the identification of future challenges and promote sustainable decision-making through forward-thinking strategies, thereby cultivating a strong orientation for future generations and environmental sustainability [106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114]. Our research indicates that a high value orientation for future generations enhances future possible performance. Many financial organizations aim to achieve environmental and economic sustainability by adopting various initiatives, such as green financing, to promote long-term sustainability. Green financing is considered a new monetary phenomenon that integrates economic benefits with environmental outcomes, prioritizing investments in eco-friendly activities such as climate change adaptation and mitigation, green industry development, and biodiversity protection [23,115]. It encompasses all forms of investments that consider environmental effects and promote sustainability [116,117]. For the banking sector, advancing green financing is essential in enabling the transition to a green economy and addressing pressing climate and environmental issues. Thus, incorporating future-studies approaches into well-structured green financing schemes, specifically agricultural green banking, will enhance the value orientation for future generations and encourage managers to adopt a visionary mindset regarding sustainable finance by identifying and addressing future challenges. The findings of this study provide critical insights into the value orientation of bankers, which is essential for the development of effective “agricultural green banking” reforms and incentives. Understanding how bankers’ attitudes influence their decisions provides a foundation for designing targeted reforms. Specifically, incentives can be structured to align with the value orientation, encouraging banks to prioritize environmentally responsible practices. Additionally, the findings support the development of policy frameworks and training programs that integrate value orientation attributes into banking operations, ensuring the adoption of developmental and environmentally sustainable practices within the banking sector. Through collaboration with banks, farmers can secure the necessary capital to implement climate-resilient technologies in the face of changing weather patterns and shifting growing seasons. Managers can further strengthen collaboration by designing financial solutions that align with farmers’ specific needs and capacities, enabling long-term sustainability and resilience in agriculture. The partnership between farmers and banks fosters a continuous cycle of adaptation and innovation, strengthening farmers’ resilience to environmental uncertainty and enhancing the agricultural sector’s capacity to respond effectively to climate challenges.

5. Conclusions

This study examines how bankers’ concerns about climate change influence their decision-making for agricultural financing and development and how these concerns are related to possible future performance. This research investigates a research question “how do bankers’ climate concerns and value orientation influence agricultural financing and development?” and the hypotheses “bankers’ climate concerns are negatively related to agricultural financing and development, whereas their value orientation for future generations is positively associated with these endeavors”. To this end, we implement questionnaire surveys to collect data on climate concerns, prosocial attitude for future generations and sociodemographic & bank related information from 596 bankers at three areas in Bangladesh. The analyses reveal that bankers who have high levels of climate concerns tend to be less optimistic about agricultural financing and development. Moreover, bankers who live in high climate-change areas tend to have more severe climate concerns and darker prospectives in agricultural financing and development than those in low climate-change areas. The findings also show that bankers who have a high value orientation for future generations are likely to be positive about future agricultural financing and development. Overall, it is suggested that agricultural financing and development shall be discouraged as climate change becomes severe, particularly affecting low-laying areas, such as Bangladesh, through the lens of bankers’ perceptions, unless the bankers possess high concerns for future generations. To address these challenges, a new agricultural financing scheme, such as “agricultural green banking”, shall be necessary to implement.

We note several limitations of this study and provide directions for future research opportunities. First, this research focuses mainly on bankers’ climate concerns with respect to future agricultural financing and development; however, the perceptions of other stakeholders who might have significant impacts are not addressed in this study. Future research should collect detailed data on stakeholders’ perceptions to provide a comprehensive understanding of these endeavors. Second, we do not account for borrowers’ perspectives, specifically how farmers’ concerns about climate change influence their ability to secure and repay loans. Emphasizing farmers’ climatic concerns regarding the securing and repaying of agricultural loans can be a focus of future studies. Third, our study examines bankers’ concerns reagrding climate change and value orientation for future agricultural financing and development from a short-term perspective, uses cross-sectional data, and does not account for potential issues of endogeneity and reverse causality. Future research could benefit from longitudinal and experimental methodologies using panel data to explore these relationships more comprehensively. Fourth, we consider climate conerns and prosocial attitude for future generations as cognitive factors influencing future agricultural financing and development; however, other cognitive and noncognitive factors, such as the knowledge level regarding various environmental aspects and prosociality, are not considered in this study. Future studies should consider key cognitive and noncognitive factors to capture the evolving dynamics of future banking performance more comprehensively. Despite these limitations, we believe that this research provides clear evidence that bankers’ concerns about climate change and their value orientation for future generations are crucial to future performance. This research is the first attempt to clarify bankers’ concerns about climate change and future generations and assess how these concerns impact future agricultural financing and development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M.A., M.R.M. and K.K.; methodology, K.M.A. and M.R.M.; software, K.M.A. and M.R.M.; validation, K.M.A., M.R.M. and K.K.; formal analysis, K.M.A. and M.R.M.; investigation, K.M.A., M.R.M. and K.K.; resources, M.R.M. and K.K.; data curation, K.M.A. and M.R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.A.; writing—review and editing, K.M.A., M.R.M. and K.K.; visualization, K.M.A., M.R.M. and K.K.; supervision, K.K.; Project administration, K.M.A. and M.R.M.; funding acquisition, M.R.M. and K.K. All authors have read and agreed to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by the International Joint Research Acceleration Fund (Strengthening International Joint Research B (22KK0020)), Research Institute for Future Design, Kochi University of Technology and JDS program, JICA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Kochi University of Technology (Approval Numbers: 38-C2 and 248).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous referees, Mitsuhiko Kataoka, Makoto Kakinaka, Kyohei Yamada and Seunghoo Lim for their helpful comments, advice and support. We extend our sincere gratitude to the Bangladesh Bank for facilitating access to valuable data from various banks and for their continued support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A presents the tables of ordered probit regressions for future agricultural financing (FAF) and future agricultural development (FAD), demonstrating the consistency of the quantitative results with those obtained from logit regressions.

Table A1.

Regression coefficients and marginal probabilities of the independent variables on future agricultural financing (FAF) in the ordered probit regression.

Table A1.

Regression coefficients and marginal probabilities of the independent variables on future agricultural financing (FAF) in the ordered probit regression.

| Future Agricultural Financing (FAF) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Marginal Probability of Responses by a Five-Point Likert-Scale | |||||

| Model 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Cognitive factors | ||||||

| Climate concerns | ||||||

| Temperature and sunlight | *** | 0.02 *** | 0.03 *** | ** | *** | ** |

| Precipitation | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Seasonality | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| Topography | *** | 0.04 *** | 0.06 *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Prosocial attitude for future generations | 0.13 *** | *** | *** | 0.01 *** | 0.04 *** | 0.01 *** |

| Climate-change areas (r a = Low climate-change area)) | ||||||

| High hazard-prone area | *** | 0.38 *** | 0.18 *** | *** | *** | *** |

| High drought-prone area | *** | 0.23 *** | 0.25 *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Sociodemographic & bank characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 0.005 | 0.0003 | 0.001 | 0.0002 | ||

| Gender () | 0.29 | * | 0.02 | 0.08 * | 0.01 * | |

| Educational background () | 0.002 | 0.003 | ||||

| Bank type () | 0.06 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.003 | ||

| Bank fixed-asset collateral () | *** | 0.10 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.002 | *** | *** |

| Agricultural loan b | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.001 | ||

*** significant at the 1 percent level, ** at the 5 percent level and * at the 10 percent level. Marginal probability indicates how much the probability of being in one number within a five-point Likert-scale measurement for a response changes when one independent variable increases by one unit, holding other factors fixed at the sample mean. a r stands for the base group, b The ordered probit regression is computed with the natural logarithm of agricultural loan.

Table A2.

Regression coefficients and marginal probabilities of the independent variables on future agricultural development (FAD) in the ordered probit regression.

Table A2.

Regression coefficients and marginal probabilities of the independent variables on future agricultural development (FAD) in the ordered probit regression.

| Future Agricultural Development (FAD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Marginal Probability of Responses by a Five-Point Likert-Scale | |||||

| Model 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Cognitive factors | ||||||

| Climate concerns | ||||||

| Temperature and sunlight | *** | 0.01 *** | 0.04 *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Precipitation | ** | 0.01 ** | 0.03 ** | * | ** | ** |

| Seasonality | 0.005 | 0.02 | ||||

| Topography | *** | 0.03 *** | 0.11 *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Prosocial attitude for future generations | 0.07 *** | *** | *** | 0.004 *** | 0.02 *** | 0.01 *** |

| Climate-change areas (r a = Low climate-change area) | ||||||

| High hazard-prone area | *** | 0.30 *** | 0.32 *** | *** | *** | *** |

| High drought-prone area | *** | 0.12 *** | 0.33 *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Sociodemographic & bank characteristics | ||||||

| Age | * | 0.001 | 0.004 * | * | * | |

| Gender () | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | ||

| Educational background () | 0.03 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.002 | ||

| Bank type () | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||

| Bank fixed-asset collateral () | *** | 0.04 *** | 0.21 *** | *** | *** | |

| Agricultural loan b | * | 0.002 * | 0.01 * | * | * | * |

*** significant at the 1 percent level, ** at the 5 percent level and * at the 10 percent level. Marginal probability indicates how much the probability of being in one number within a five-point Likert-scale measurement for a response changes when one independent variable increases by one unit, holding other factors fixed at the sample mean. a r stands for the base group, b The ordered probit regression is computed with the natural logarithm of agricultural loan.

References

- Durán-Sandoval, D.; Uleri, F.; Durán-Romero, G.; López, A. Food, climate change, and the challenge of innovation. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, N.; Alexander, L. Has the climate become more variable or extreme? Progress 1992–2006. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2007, 31, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumel, D. Assessing climate change vulnerability: A conceptual and theoretical review. J. Sustain. Environ. Manag. 2022, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The Impact of Disasters on Agriculture and Food Security 2023— Avoiding and Reducing Losses Through Investment in Resilience; Technical Report; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, G.; Alam, K.; Mushtaq, S. Climate change perceptions and local adaptation strategies of hazard-prone rural households in Bangladesh. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 17, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma, K.; Kotani, K. Salinity and water-related disease risk in coastal Bangladesh. EcoHealth 2021, 18, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Siddik, A.; Zheng, G.; Masukujjaman, M.; Bekhzod, S. The effect of green banking practices on banks’ environmental performance and green financing: An empirical study. Energies 2022, 15, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buranatrakul, T.; Swierczek, F. Climate change strategic actions in the international banking industry. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2018, 19, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Siddik, A.; Masukujjaman, M.; Fatema, N.; Alam, S. Green finance development in Bangladesh: The role of private commercial banks (PCBs). Sustainability 2021, 13, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Al Amin, M.; Moon, Z.; Afrin, F. Role of environmental sustainability, psychological and managerial supports for determining bankers’ green banking usage behavior: An integrated framework. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 3751–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmucci, D.; Ferraris, A. Climate change inaction: Cognitive bias influencing managers’ decision making on environmental sustainability choices. The role of empathy and morality with the need of an integrated and comprehensive perspective. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1130059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syropoulos, S.; Markowitz, E. Responsibility towards future generations is a strong predictor of proenvironmental engagement. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N. Foreign Aid to Agriculture: Review of Facts and Analysis; Technical Report; IFPRI Discussion Paper No. 01053; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Wang, Y. Financing sustainable agriculture under climate change. J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 13, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis; Technical Report, Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessement Report; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development; Technical Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. Green Finance in Bangladesh: Policies, Institutions, and Challenges; Technical Report; Working Paper No. 892; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, M. Agrarian Transition and Livelihoods of The Rural Poor: Agricultural Credit Market; Technical Report; Unnayan Onneshan; The Innovators: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M. Policies and performances of agricultural/rural credit in Bangladesh: What is the influence on agricultural production? Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 6440–6452. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, T.; Fonta, W. Climate change and financing adaptation by farmers in northern Nigeria. Financ. Innov. 2018, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, F. Experiences with Traditional Compensatory Finance Schemes and Lessons from FLEX; Technical Report; Working Paper No. 12; Department of Economics and Statistics, University of Calabria: Calabria, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, M.; Seshadri, U.; Kumar, P.; Aqdas, R.; Patwary, A.; Riaz, M. Nexus between green finance and climate change mitigation in N-11 and BRICS countries: Empirical estimation through difference in differences (DID) approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 6504–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Fatema, N. Factors affecting the sustainability performance of financial institutions in Bangladesh: The role of green finance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alauddin, M.; Biswas, J. Agricultural credit in Bangladesh: Trends, patterns, problems and growth impacts. Jahangirnagar Econ. Rev. 2014, 25, 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Alauddin, M.; Sarker, M. Climate change and farm-level adaptation decisions and strategies in drought-prone and groundwater-depleted areas of Bangladesh: An empirical investigation. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 106, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Sen, K.; Riva, F. Behavioral determinants of nonperforming loans in Bangladesh. Asian J. Account. Res. 2020, 5, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzi, M.; Schminke, M. Assembling fragments into a lens: A review, critique, and proposed research agenda for the organizational work climate literature. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 634–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N. Organisational sustainability policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.; Parker, S.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N. Employee green behavior: A theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. The relationship between pro-environmental attitude and employee green behavior: The role of motivational states and green work climate perceptions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 7341–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasebrook, J.; Michalak, L.; Wessels, A.; Koenig, S.; Spierling, S.; Kirmsse, S. Green behavior: Factors influencing behavioral intention and actual environmental behavior of employees in the financial service sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartadjumena, E.; Rodgers, W. Executive compensation, sustainability, climate, environmental concerns, and company financial performance: Evidence from Indonesian commercial banks. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhan, A.; Rahmanti, W. The impact of sustainability reporting on company performance. J. Econ. Bus. Account. Ventur. 2012, 15, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.; Archuleta, W.; Cantu, C. Politics, concern for future generations, and the environment: Generativity mediates political conservatism and environmental attitudes. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoarde-Segot, T. Sustainable finance. A critical realist perspective. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2019, 47, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syropoulos, S.; Markowitz, E. Our responsibility to future generations: The case for intergenerational approaches to the study of climate change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 87, 102006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syropoulos, S.; Markowitz, E. Perceived responsibility towards future generations and environmental concern: Convergent evidence across multiple outcomes in a large, nationally representative sample. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 76, 101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienes, C. Actions and intentions to pay for climate change mitigation: Environmental concern and the role of economic factors. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 109, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.; Akhtar, R.; Afroz, R.; Al-Amin, A.; Kari, F. Pro-environmental behavior and public understanding of climate change. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2015, 20, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, V.; Can, Y. Impact of knowledge, concern and awareness about global warming and global climatic change on environmental behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 6245–6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijndam, S.; Beukering, P. Understanding public concern about climate change in Europe, 2008–2017: The influence of economic factors and right-wing populism. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.; Rauvola, R.; Rudolph, C.; Zacher, H. Employee green behavior: A meta-analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. Role of agriculture in Bangladesh economy: Uncovering the problems and challenges. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. 2017, 6, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, A.; Hossain, M. Bangladesh’s agricultural growth and development over fifty years. In Towards a Sustainable Economy: The Case of Bangladesh; Hossain, M., Ahmad, Q., Islam, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Yeasmin, S.; Haque, S.; Adnan, K.; Parvin, M.; Rahman, M.; Rahman, K.; Salman, M.; Hossain, M. Factors influencing demand for, and supply of, agricultural credit: A study from Bangladesh. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, Y. The development of banking sector in Bangladesh. Southeast Univ. J. Bus. Stud. 2006, 2, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Y.; Adhikary, B. A ‘bank rent’ approach to understanding the development of the banking system in Bangladesh. Contemp. South Asia 2010, 18, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BB. Agricultural & Rural Credit Policy and Programme for the FY 2013–2014; Technical Report; Bangladesh Bank: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- BB. Annual Report 2022–2023; Technical Report; Bangladesh Bank: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Azad, A.; Choudhury, N.; Wadood, S. Impact of agricultural credit on agricultural production: Evidence from Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2023, 40, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.; Carins, J.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Can social cognitive theory influence breakfast frequency in an institutional context: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, S.; Gao, C.; Brennan, N.; Fava, N.; Simmons, M.; Baker, D.; Zbukvic, I.; Rickwood, D.; Brown, E.; Smith, C.; et al. Climate change concerns impact on young Australians’ psychological distress and outlook for the future. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Stren, P. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.; Nguyen, B.; Mutum, D.; Yap, S. Pro-environmental behaviours and value-belief-norm theory: Assessing unobserved heterogeneity of two ethnic groups. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, S. The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Demski, C.; Capstick, S. How personal experience affects perception of and decisions related to climate change: A psychological view. Weather Clim. Soc. 2021, 13, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluckhohn, F.; Strodtbeck, F. Variations in Value Orientations; Row, Peterson: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Gajanayake, R.; Johnson, L.; Daronkola, H.; Perera, C. Impact of households’ future orientation and values on their willingness to install solar photovoltaic systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafizur, R.; Asma, K.; Islam, M.; Kotani, K. Drivers for sustainable food purchase intentions: Prosocial attitudes for future generations and environmental concerns. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADB. Bangladesh Climate and Disaster Risk Atlas: Hazards—Volume 1; Technical Report; Planning Commission, Ministry of Planning and Asian Development Bank: Dhaka, Bangladesh; Manila, Philippines, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman, K.; Ahmed, F.; Nazrul, I. Modeling on climate induced drought of north-western region, Bangladesh. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2016, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBS. Report on Agriculture and Rural Statistics 2018; Technical Report; Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- BB. Introduction—Bangladesh Bank; Technical Report; Bangladesh Bank: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bujang, M.; Sa’at, N.; Bakar, T.; Joo, L. Sample size guidelines for logistic regression from observational studies with large population: Eemphasis on the accuracy between statistics and parameters based on real life clinical data. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 25, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morselli, D.; Passini, S. Measuring prosocial attitudes for future generations: The social generativity scale. J. Adult Dev. 2015, 22, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.; Vleet, S.; Cantu, C. Gratitude mediates perceptions of previous generations’ prosocial behaviors and prosocial attitudes toward future generations. J. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 16, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, N. Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychol. Assess. 1996, 8, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, S.; Cheek, J. The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. J. Personal. 1986, 54, 106–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 4th ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A.; Trivedi, P. Microeconometrics Using Stata: Cross-Sectional and Panel Regression Methods; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2022; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2006; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.; Kotani, K.; Managi, S. Nature dependence and seasonality change perceptions for climate adaptation and mitigation. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dong, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, N. The effect of climate change on firms’ debt financing costs: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Shahbaz, M.; Kyriakou, I. Temperature fluctuations, climate uncertainty, and financing hindrance. J. Reg. Sci. 2025, 65, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E. The economic determinants of land degradation in developing countries. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. Biol. Sci. 1997, 352, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Kotani, K. Changing seasonality in Bangladesh. Reg. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadilha, S.; Vaz, S. Prospection as a sustainability virtue: Imagining futures for intergenerational ethics. Z. Ethik Moralphilosophie 2023, 6, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N. Thirty years of prospect theory in economics: A review and assessment. J. Econ. Perspect. 2013, 27, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making: Part I; World Scientific: Singapore, 2013; pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Osberghaus, D. Prospect theory, mitigation and adaptation to climate change. J. Risk Res. 2017, 20, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ramirez, J.; Arora, P.; Podesta, G. Using insights from prospect theory to enhance sustainable decision making by agribusinesses in Argentina. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefroid, M.; Plattfaut, R.; Niehaves, B. How to measure the status quo bias? A review of current literature. Manag. Rev. Q. 2023, 73, 1667–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazutis, D.; Eckardt, A. Sleepwalking into catastrophe: Cognitive biases and corporate climate change inertia. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2017, 59, 74–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keh, H.; Foo, M.; Lim, B. Opportunity evaluation under risky conditions: The cognitive processes of entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 27, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, C. Implicit bias training is dead, long live implicit bias training: The evolving role of human resource development in combatting implicit bias within organisations. In The Emerald Handbook of Work, Workplaces and Disruptive Issues in HRM; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2022; pp. 381–396. [Google Scholar]

- Enke, B.; Gneezy, U.; Hall, B.; Martin, D.; Nelidov, V.; Offerman, T.; Van, J. Cognitive biases: Mistakes or missing stakes? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2023, 105, 818–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprengel, D.; Busch, T. Stakeholder engagement and environmental strategy—The case of climate change. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Fowler, H.; Slater, D.; Johnson, J.; Ellstrand, A.; Romi, A. Beyond “Does it pay to be green?” A meta-analysis of moderators of the CEP—CFP relationship. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bătae, O.; Dragomir, V.; Feleagă, L. The relationship between environmental, social, and financial performance in the banking sector: A European study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 290, 125791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosbois, D.; Fennell, D. Determinants of climate change disclosure practices of global hotel companies: Application of institutional and stakeholder theories. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakhem, A.; Palmer, D. Normative stakeholder theory. In Stakeholder Management (Business and Society 360); Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017; Volume 1, Chapter 3; pp. 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Valentinov, V.; Hajdu, A. Integrating instrumental and normative stakeholder theories: A systems theory approach. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2021, 34, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, W. Foundations of Futures Studies: Human Science for a New Era; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Helm, R. The vision phenomenon: Towards a theoretical underpinning of visions of the future and the process of envisioning. Futures 2009, 41, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phdungsilp, A. Futures studies’ backcasting method used for strategic sustainable city planning. Futures 2011, 43, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.; Daim, T.; Jetter, A. A review of scenario planning. Futures 2013, 46, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpunar, K.; Spreng, R.; Schacter, D. A taxonomy of prospection: Introducing an organizational framework for future-oriented cognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 18414–18421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ricoy, I.; Gosseries, A. Institutions for Future Generations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bibri, S.; Krogstie, J. Generating a vision for smart sustainable cities of the future: A scholarly backcasting approach. Eur. J. Futur. Res. 2019, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, R.; Oliveira, L. Backcasting for sustainability—An approach to education for sustainable development in management. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchiato, R. Environmental uncertainty, foresight and strategic decision making: An integrated study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2012, 79, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.; Inayatullah, S.; Burgman, M.; Sutherland, W.; Wintle, B. Strategic foresight: How planning for the unpredictable can improve environmental decision-making. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, A.; Tapio, P.; Varho, V.; Järvi, T.; Banister, D. Pluralistic backcasting: Integrating multiple visions with policy packages for transport climate policy. Futures 2014, 60, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, J.; Neale, T. A critical review of the application of environmental scenario exercises. Futures 2015, 73, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Lara, J.; Banister, D. Collaborative backcasting for transport policy scenario building. Futures 2018, 95, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, D.; Laurent, L.; Menthière, N.; Schmitt, B.; Béthinger, A.; David, B.; Didier, C.; Châtelet, J. Multiple visions of the future and major environmental scenarios. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, R.; Nakagawa, Y.; Kotani, K. Exploring the possibility of linking and incorporating future design in backcasting and scenario planning. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, A.; Nakagawa, Y.; Timilsina, R.; Kotani, K.; Saijo, T. Taking the perspectives of future generations as an effective method for achieving sustainable waste management. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1526–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahen, M.; Kotani, K.; Saijo, T. Intergenerational sustainability is enhanced by taking the perspective of future generations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.; Murtaz, M. Green financing in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Finance for Sustainable Growth and Development; Jahur, M., Uddin, S., Eds.; Department of Finance, Faculty of Business Administration, University of Chittagong: Chittagong, Bangladesh, 2018; pp. 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Volz, U.; Böhnke, J.; Knierim, L.; Richert, K.; Roeber, G.; Eidt, V. Financing the Green Transformation: How to Make Green Finance Work in Indonesia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khairunnessa, F.; Vazquez-Brust, D.; Yakovleva, N. A review of the recent developments of green banking in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).