Decreasing Snow Cover and Increasing Temperatures Are Accelerating in New England, USA, with Long-Term Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How temperatures are changing in each of the New England states annually and seasonally, if the warming in New England is accelerating like other areas in the world, and if there are variations in the warming between different parts of New England.

- (2)

- The research explores how snow cover is changing in New England annually and seasonally as the temperatures warm, if there are variations in snow cover loss between different parts of New England, and if there is a relationship between declining snow cover and increasing temperatures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Air Temperature Analysis

2.2. Land Surface Temperature Analysis

2.3. Snow Cover Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Air Temperature Change

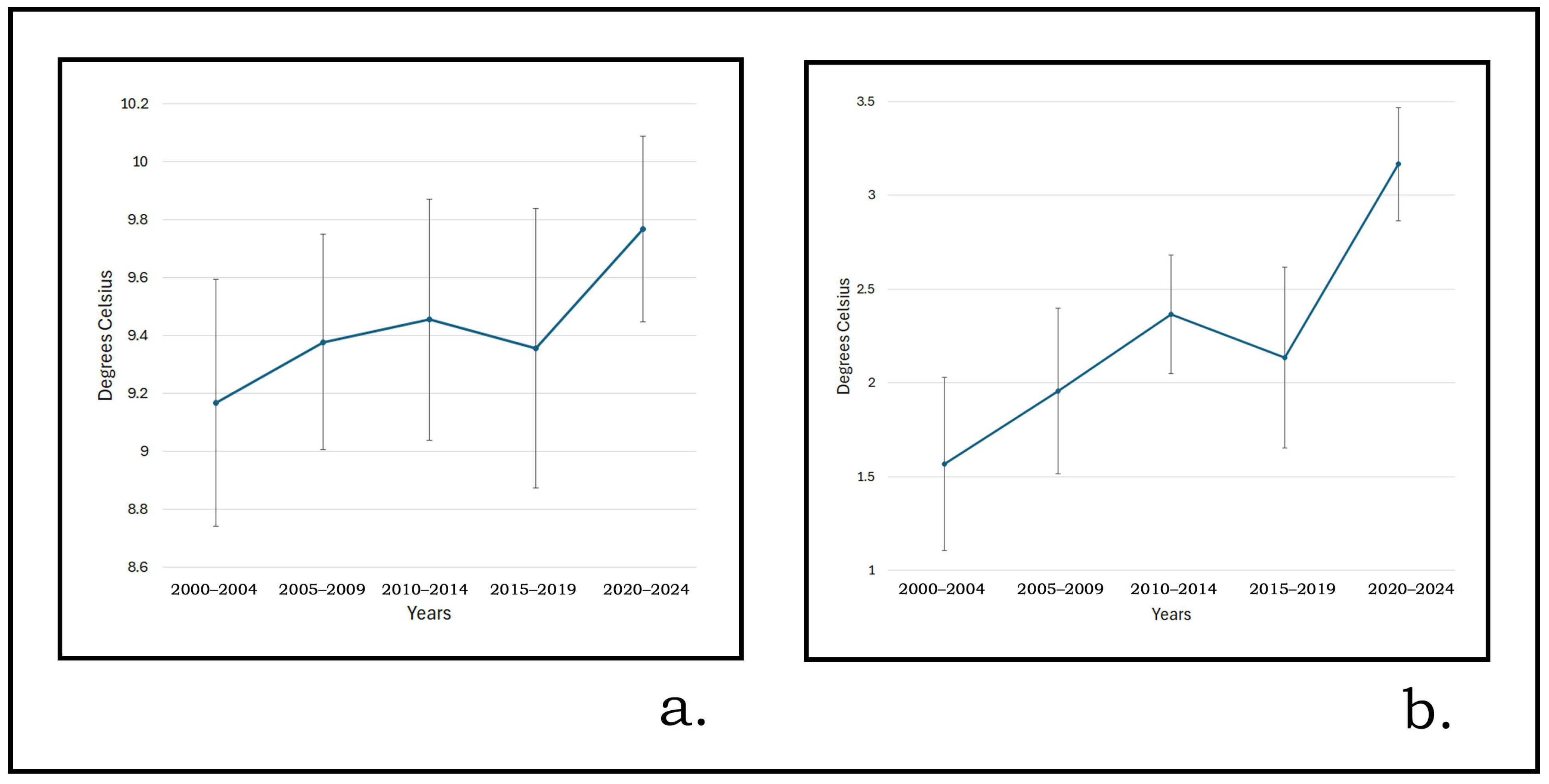

3.2. Land Surface Temperature Change

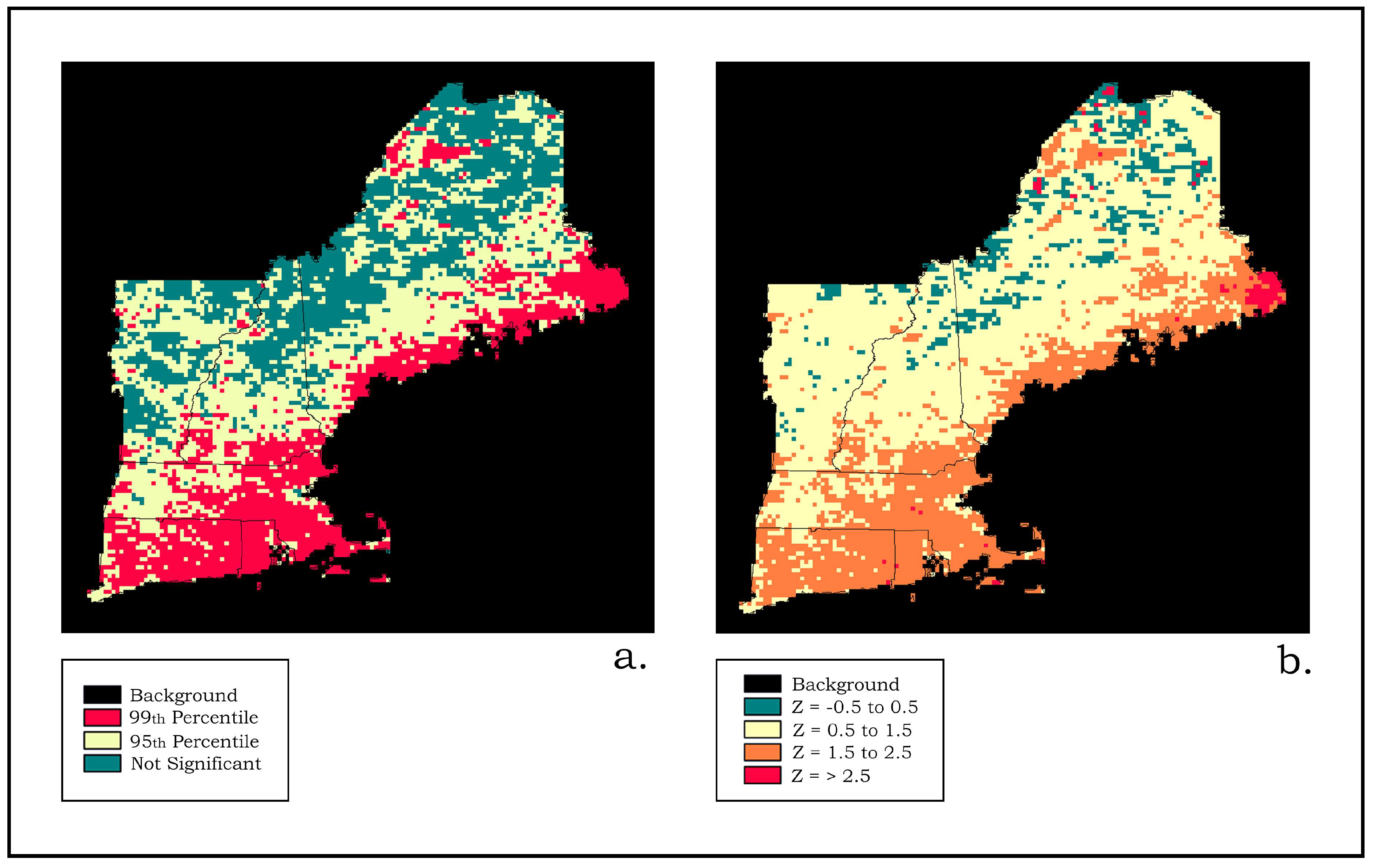

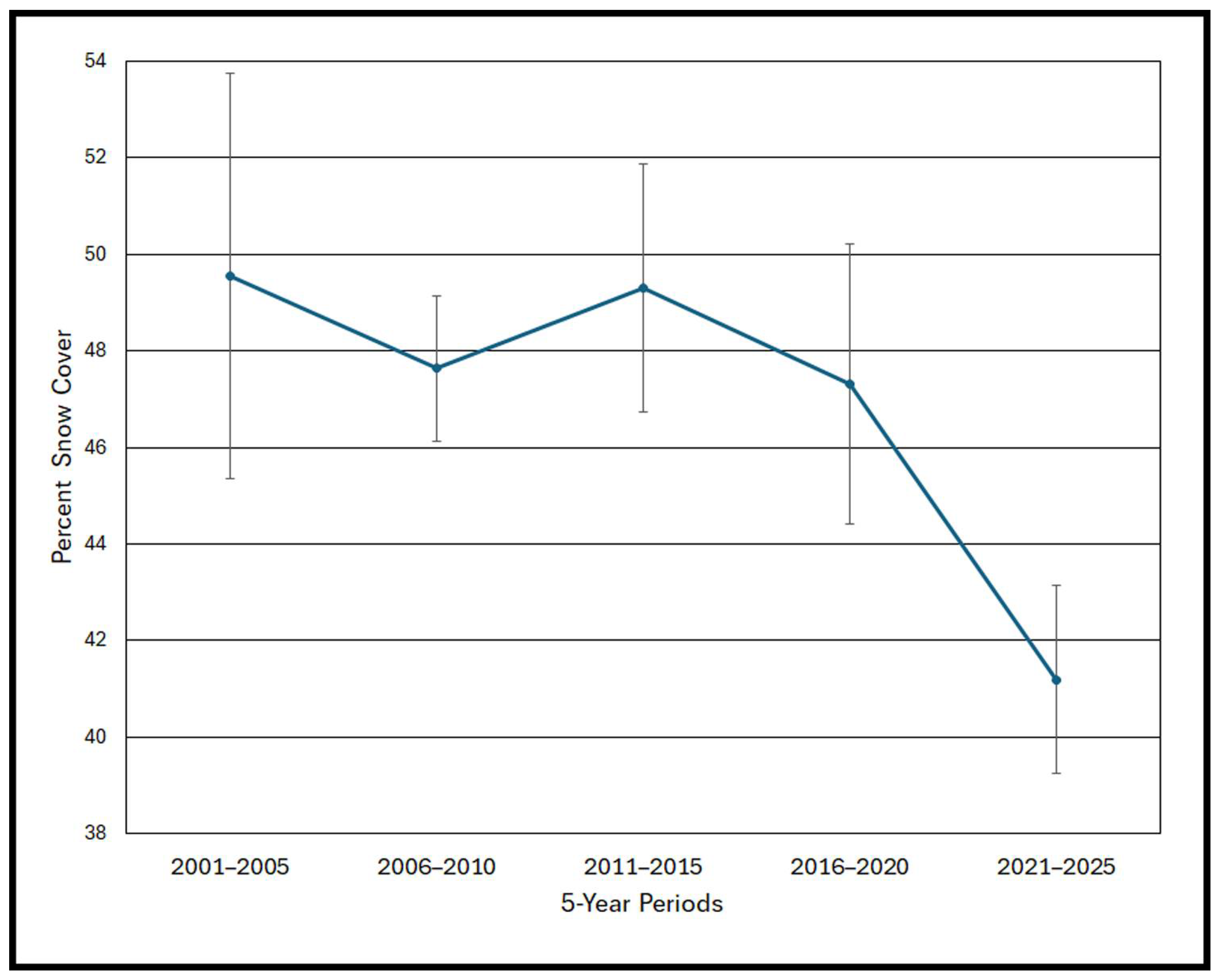

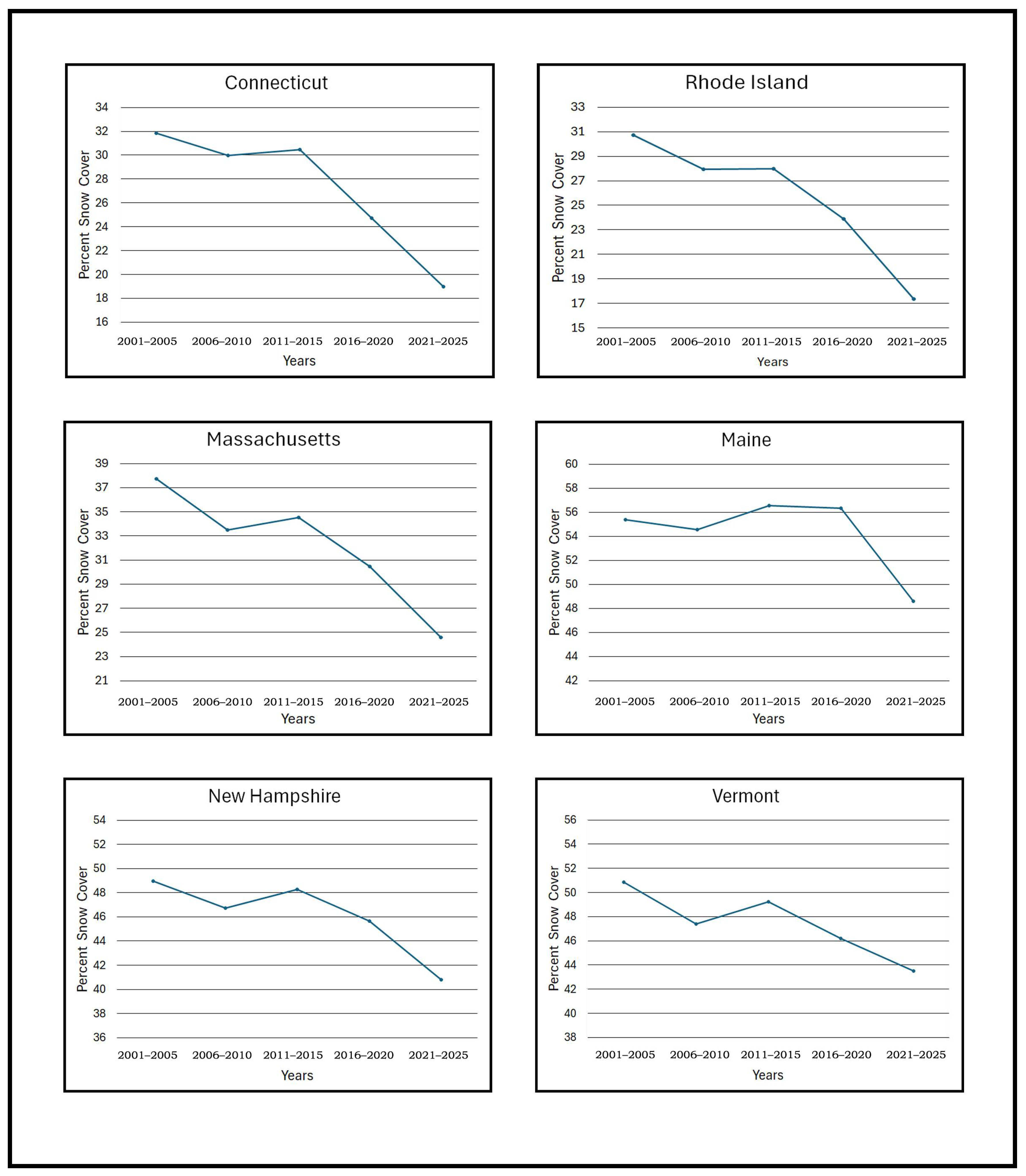

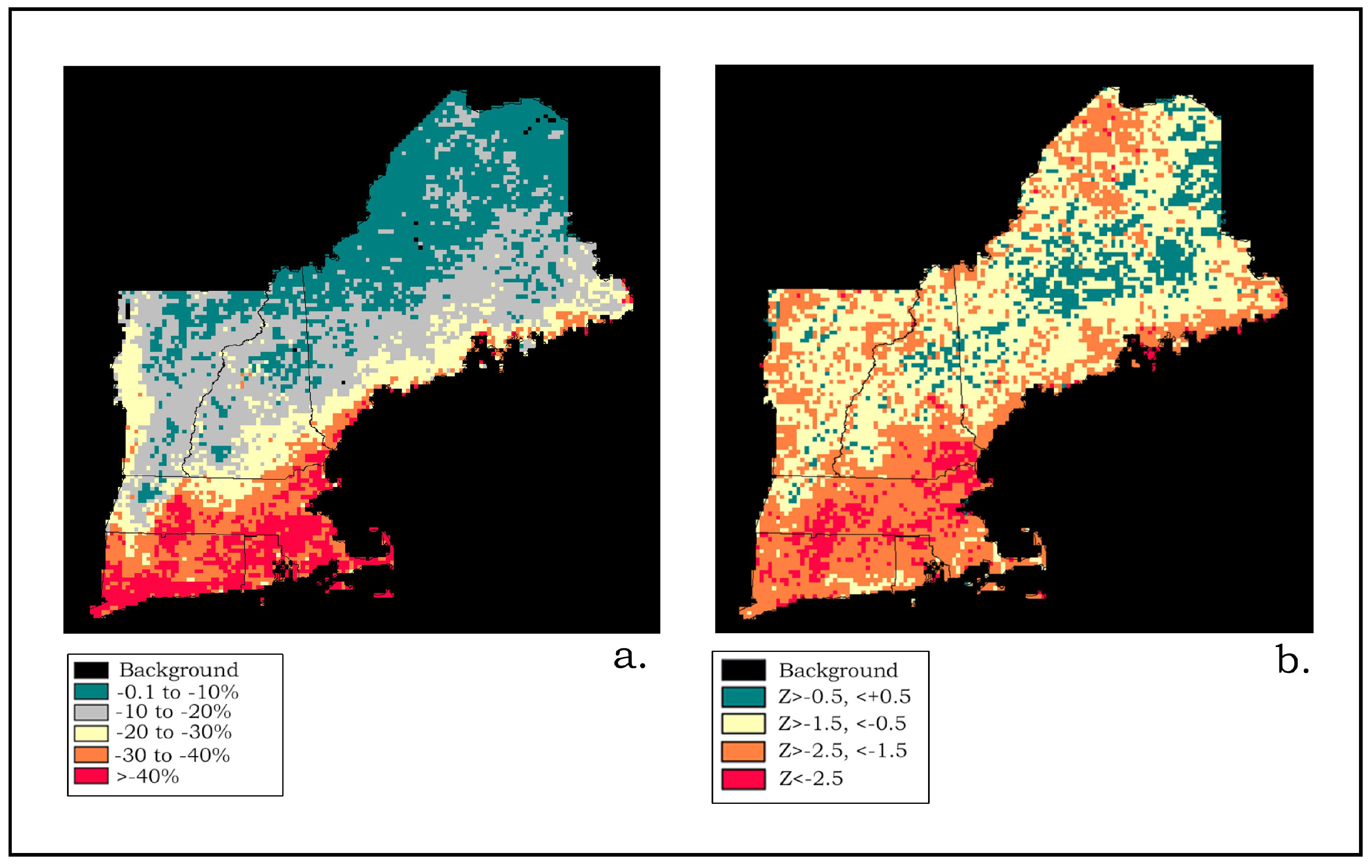

3.3. Snow Cover Change

4. Discussion

4.1. Important Observations

- (1)

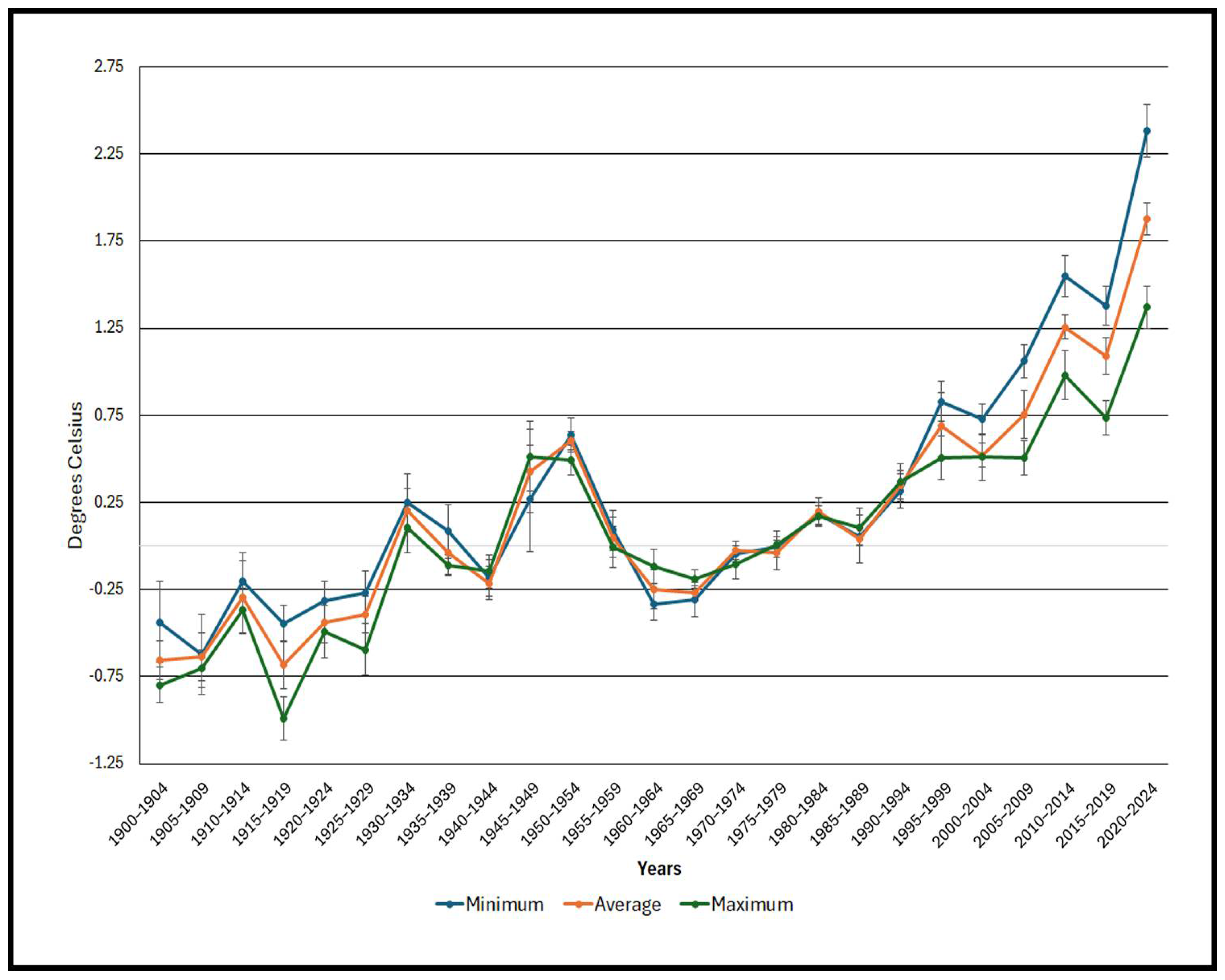

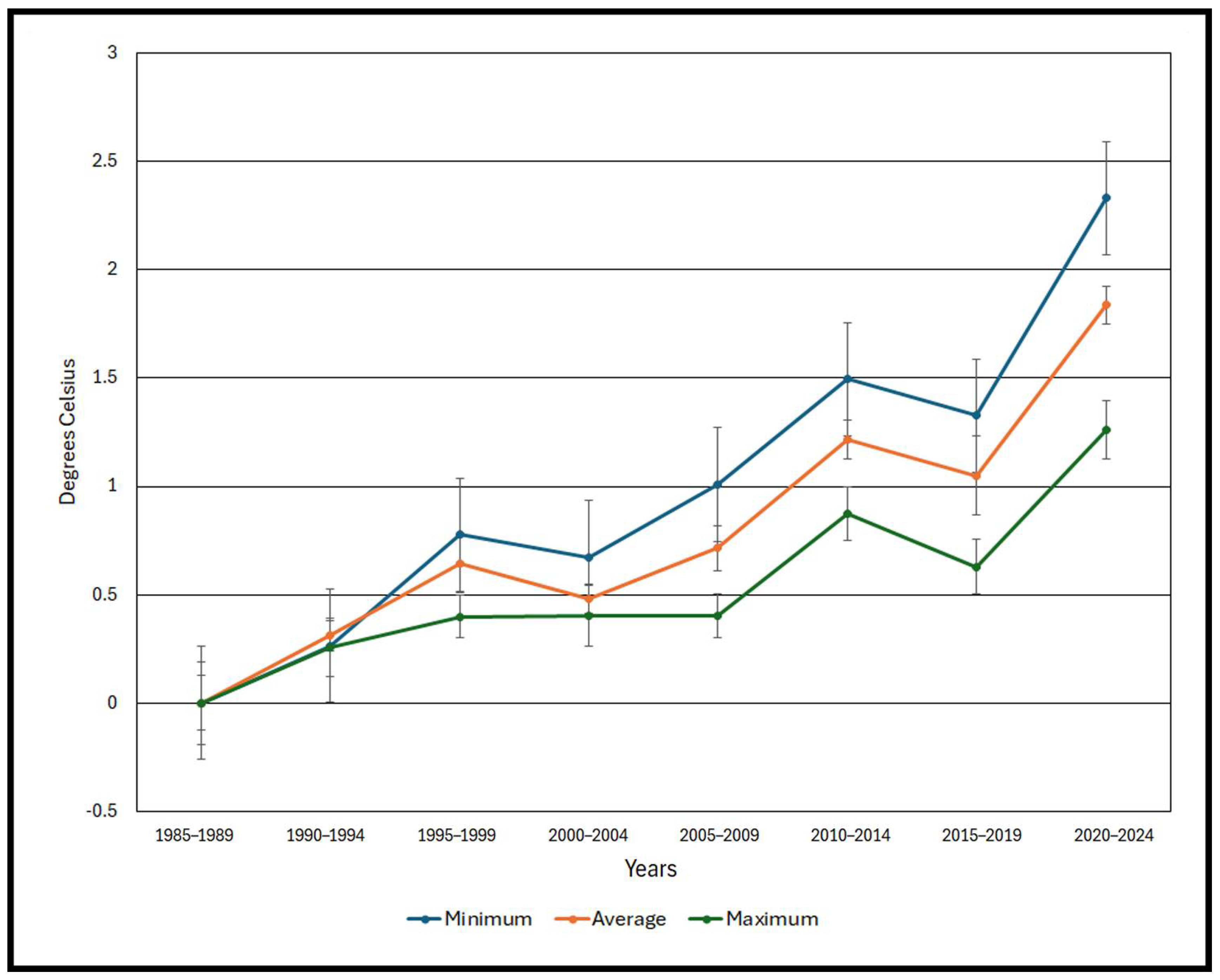

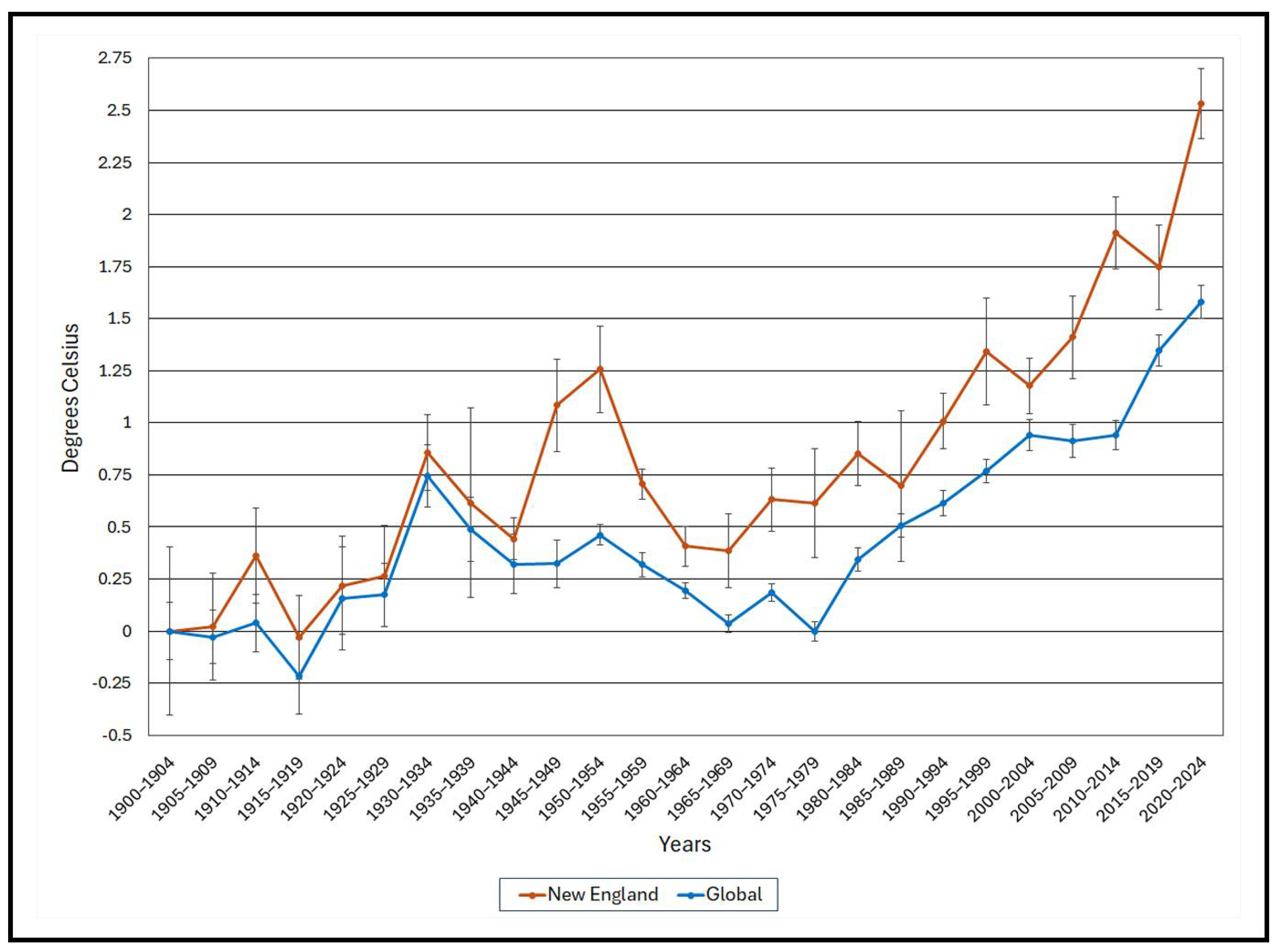

- The existence of three major periods of change in New England are as follows: (1) 1900 to the early 1950s with about a 1 °C temperature rise, (2) the 1950s to the late 1960s with a decline of about 0.5 °C, and (3) the 1970s to 2024 with a rise of about 2 °C, with a sharp rise in temperature since the mid-1980s. New England’s pattern of change roughly parallels the global patterns of change, though New England warms more quickly overall. The early warming period from 1900 to 1950 was driven by both natural factors (higher solar irradiance, volcanic activity, internal variability) and early anthropogenic forcing, from greenhouse gases and land-use changes [88]. The decline in temperatures from the early 1950s to the 1970s is due to air pollution and increased aerosols in the atmosphere [89], which reflected incoming solar radiation out of the Earth system and affected New England more than the globe. The last period of warming from the 1970s to 2025 has been driven largely by human activity, especially the burning of fossil fuels as well as land cover change increasing atmospheric greenhouse gases along with declining atmospheric aerosols [3].

- (2)

- There are strong seasonal variations in the warming of New England where winter is warming almost twice as fast as any other season, and the winter season shows more consistent significant changes than any of the seasons as indicated in both the air temperature and LST data sets. Europe, across the Atlantic Ocean from New England, which is warming just as fast, saw minimal variations between seasons, though spring and summer are warming faster than the other seasons and the European winter exhibits more variation than in New England [11,84]. Other regions of the world that once experienced prominent winter warming are now warming faster in the spring including Central Asia and northwest China [85,90]. With New England warming the fastest in winter, snow cover has been declining throughout the region, paralleling the warming temperatures. The seasonal changes occurring in New England reflect global and hemispheric models which show spring arriving earlier and autumn arriving later, and projections estimate that summer will last nearly half a year and winter less than 2 months by 2100 [21]. Changes in temperature for different seasons not only alter the boundaries between seasons but also change crop phenology, disrupt migration and animal reproductive periods, expand the range of invasive species, and lead to various risks and disasters, such as increasing heatwaves, wildfires, floods, and early snowmelt among other climate-induced seasonal problems [91].

- (3)

- In New England, annual minimum air temperatures are rising faster than maximum air temperatures and nighttime LST are rising faster than daytime LST, reducing the diurnal temperature range (DTR), especially since the 1980s for the air temperatures. Minimum air temperatures in every season, except springtime, are rising faster than maximum air temperatures, especially in the winter when they have warmed almost 5 °C. In every state, except RI, annual, fall and winter minimums have been rising faster than maximum temperatures, and in all states except RI and VT summer, minimums are rising fastest. Globally, the opposite is happening where maximum temperatures are rising faster with a major reversal happening around 1988, which affected nearly half of the world’s land areas, particularly in central Eurasia, South America, Western Australia, Northern Europe, and Greenland [92]. Interestingly, in the late 1980s is when the minimum temperatures in New England started to increase much faster than maximum values. With minimum air temperatures in New England rising faster than maximum temperatures, particularly in late autumn, winter, and early spring, results in precipitation arriving as rain instead of snow more often [93,94]. This is reflected in the loss of snow cover seen throughout New England in this study. The LST data showed a similar pattern to the air temperature data with nighttime temperatures (minimum) rising faster, and more significantly, than the daytime (maximum) temperatures. Other LST studies have found nighttime LST warming faster and more significantly than daytime LST [50].

- (4)

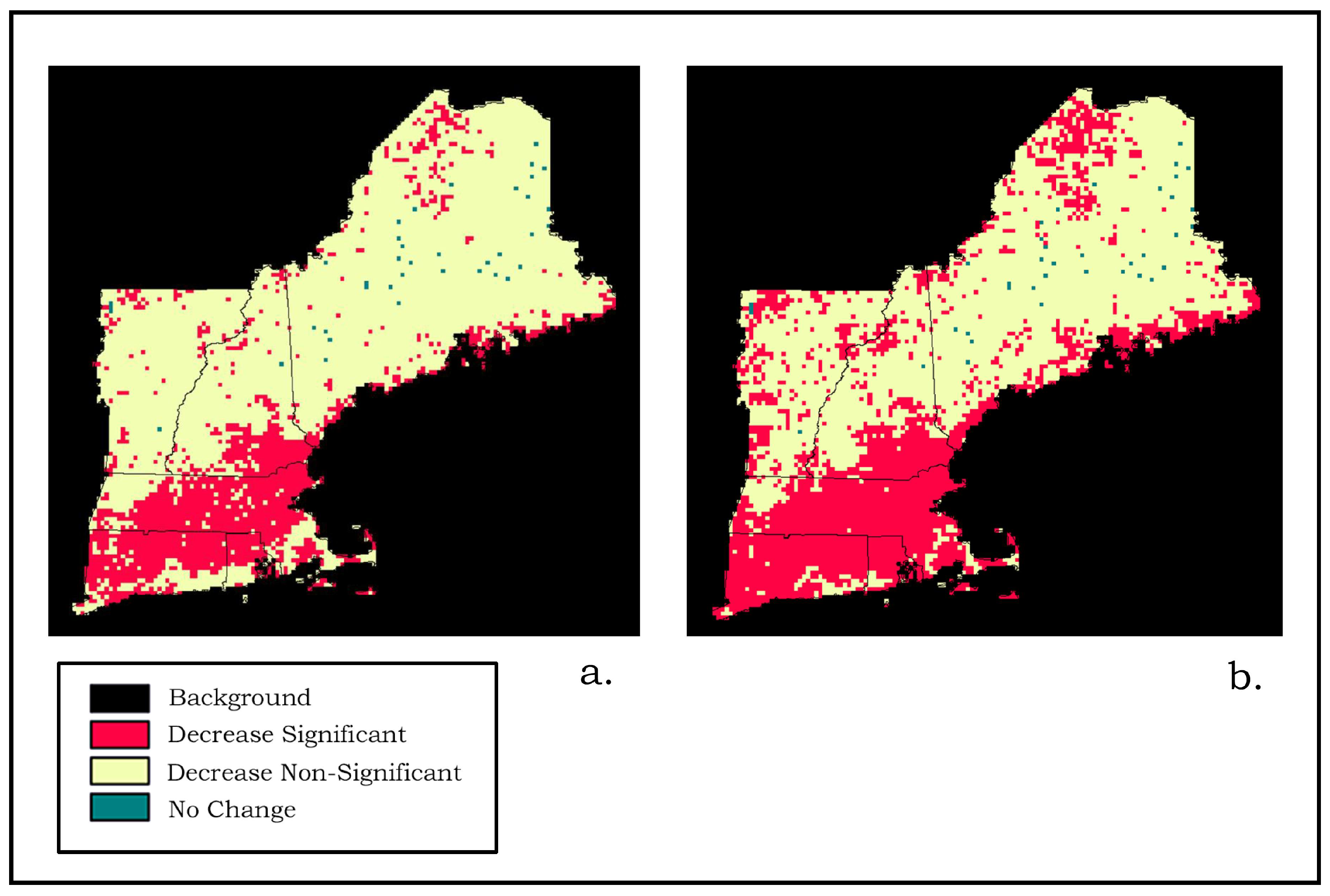

- Snow cover is decreasing throughout New England, especially in southern New England (CT, RI, MA). Although snow cover has been declining quicker in southern New England, snow cover decline is now also accelerating in northern New England (ME, NH, VT). Snow cover has broadly been declining across the globe, especially in the spring season [26,95]. Southern New England is a global hot spot of snow cover decline being in the top 5% of regions losing snow cover between 2000 and 2020, which also includes the Andes of South America, Northeast China, and Southeast Europe [26]. The warming that New England has been experiencing, especially the increasing minimum and nighttime temperatures, has allowed the snow/rain ratio to decline where cold weather snow is now falling as rain more often [96]. Global studies have shown that at the mid- and low-latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, the snow/rain ratio has a decreasing trend, with latitude and altitude being strong predictors of changes in this ratio [97,98]. The ratio of snow to total precipitation (s/p) is a hydrologic indicator that is sensitive to climate variability, and this ratio has been declining in New England for some decades [93].

- (5)

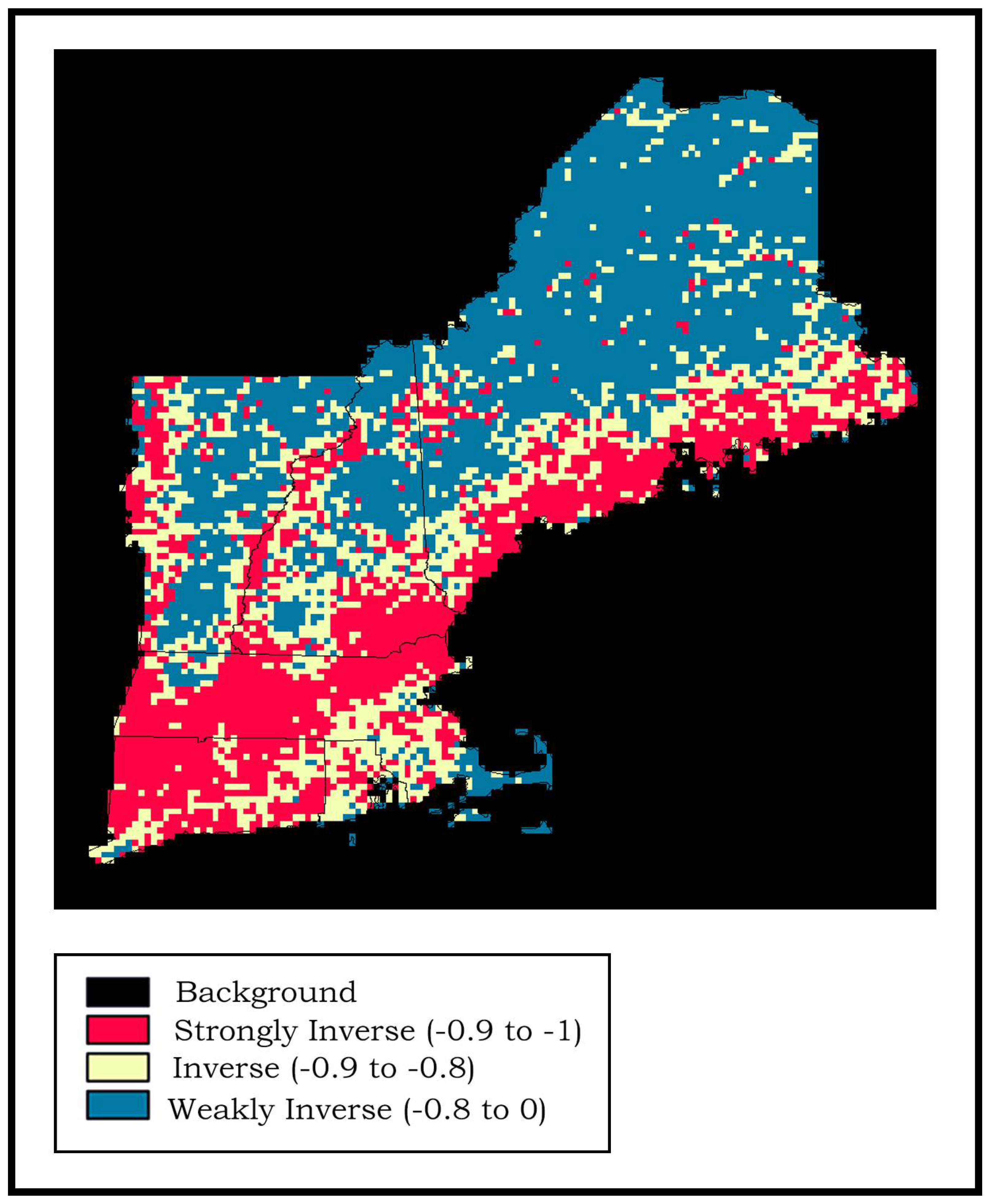

- Declining snow cover appears to be a factor in the warming of some areas in New England. A time series regression between snow cover data and LST data showed a widespread strong inverse relationship across southern New England and coastal ME, areas of intense snow cover loss. An inverse relationship means that as snow cover declines, land surface temperatures increase. Southern New England sits at the sweet spot of the mid-latitudes where warming is driving the snow/rain ratio to decline, and thus, snow cover days are declining, which, in turn, might be warming New England with the snow albedo feedback [99]. Snow is highly reflective and sends incoming solar radiation back to space. In the absence of snow, more of the incoming solar radiation gets absorbed and not reflected, thus warming the land [23,99]. The close relationship between areas of snow cover loss and LST warming, as revealed in the time series regression, indicates that the decline of snow cover might be influencing the warming of New England. Not only are snow cover days disappearing in New England, but snowpack is decreasing as well. Steep snowpack reductions, between 10% and 20% per decade, have occurred in New England along with snowpack declines in Southwestern United States, as well as in Central and Eastern Europe [100,101].

- (6)

- Perhaps the most striking result from this study is the acceleration of air temperature warming, LST warming, and snow cover decline in New England. Global temperatures have been consistently rising since the 1970s [102] and accelerating since the 1980s [3], which we also see in the New England data, but even more striking is the acceleration over the last five years in both air temperature warming and LST warming as well as in snow cover decline. Annual air temperatures for New England and every state have accelerated in the past five years, New England’s nighttime and daytime LST has accelerated in the past five years, and annual snow cover decline for every state, except VT, has accelerated in the past five years while VT’s acceleration has been over the past ten years. Even ME, which has had a relatively consistent high percentage of annual snow cover, saw an acceleration of snow cover decline.

4.2. Implications for Temperature and Snow Cover Change

- (1)

- Warming temperatures and health concerns

- (2)

- Sea-level rise and coastal flooding

- (3)

- Extreme precipitation events, flooding, and drought

- (4)

- Impacts on agriculture, fisheries, and ecosystems

- (5)

- Impacts on forests

- (6)

- Economic and social costs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, M.R.; Friedlingstein, P.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Jenkins, S.; Malhi, Y.; Mitchell-Larson, E.; Peters, G.P.; Rajamani, L. Net zero: Science, origins, and implications. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 849–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghussain, L. Global warming: Review on driving forces and mitigation. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2019, 38, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.E.; Kharecha, P.; Sato, M.; Tselioudis, G.; Kelly, J.; Bauer, S.E.; Ruedy, R.; Jeong, E.; Jin, Q.; Rignot, E.; et al. Global warming has accelerated: Are the united nations and the public well-informed? Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 67, 6–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation strategies, and mitigation options in the socio-economic and environmental sectors. J. Environ. Sci. Econ. 2023, 2, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, R.K.; Allen, M.R.; Barros, V.R.; Broome, J.; Cramer, W.; Christ, R.; Church, J.A.; Clarke, L.; Dahe, Q.; Dasgupta, P.; et al. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Dey, A.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, R.; Singh, H.P. Socio-economic impacts of climate change. In Climate Impacts on Sustainable Natural Resource Management; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 237–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.; Beverley, J.D.; Bracegirdle, T.J.; Catto, J.; McCrystall, M.; Dittus, A.; Freychet, N.; Grist, J.; Hegerl, G.C.; Holland, P.R.; et al. Emerging signals of climate change from the equator to the poles: New insights into a warming world. Front. Sci. 2024, 2, 1340323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus. Why Are Europe and the Arctic Heating up Faster than the Rest of the World? 14 July 2025. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/why-are-europe-and-arctic-heating-faster-rest-world (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Clima, T.H.E.R.; Te, W. State of the Climate in Asia; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Karmalkar, A.V.; Horton, R.M. Drivers of exceptional coastal warming in the northeastern United States. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus. The 2024 Annual Climate Summary: Global Climate Highlights. 10 January 2025. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/global-climate-highlights-2024?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Tran, D.X.; Pla, F.; Latorre-Carmona, P.; Myint, S.W.; Caetano, M.; Kieu, H.V. Characterizing the relationship between land use land cover change and land surface temperature. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 124, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.S.; Young, J.S. Overall Warming with Reduced Seasonality: Temperature Change in New England, USA, 1900–2020. Climate 2021, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, A.R.; Avery, C.W.; Easterling, D.R.; Kunkel, K.E.; Stewart, B.C.; Maycock, T.K. Fifth National Climate Assessment; U.S. Global Change Research Program, United States National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhoe, K.; Wake, C.P.; Huntington, T.G.; Luo, L.; Schwartz, M.D.; Sheffield, J.; Wood, E.; Anderson, B.; Bradbury, J.; DeGaetano, A.; et al. Past and future changes in climate and hydrological indicators in the US Northeast. Clim. Dyn. 2007, 28, 381–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, T.G.; Richardson, A.D.; McGuire, K.J.; Hayhoe, K. Climate and hydrological changes in the northeastern United States: Recent trends and implications for forested and aquatic ecosystems. Can. J. For. Res. 2009, 39, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresser, C.A.L.E.B.; Gentile, E.; Lyons, R.; Sullivan, K.; Balsari, S. Climate change and health in New England: A review of training and policy initiatives at health education institutions and professional societies. RI Med. J. 2021, 104, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.; Baker, S.; Young, S.S. Preserving History: Assessments and Climate Adaptations at the House of the Seven Gables in Salem, Massachusetts, USA. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World map of Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinski, G.A.; Keim, B.D. New England Weather, New England Climate; University Press of New England: Lebanon, NH, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Guan, Y.; Wu, L.; Guan, X.; Cai, W.; Huang, J.; Dong, W.; Zhang, B. Changing lengths of the four seasons by global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL091753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ma, M.; Wu, X.; Yang, H. Snow cover and vegetation-induced decrease in global albedo from 2002 to 2016. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mote, T.L. On the role of snow cover in depressing air temperature. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2008, 47, 2008–2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bormann, K.J.; Brown, R.D.; Derksen, C.; Painter, T.H. Estimating snow-cover trends from space. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 924–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebault, K.; Young, S. Snow cover change and its relationship with land surface temperature and vegetation in northeastern North America from 2000 to 2017. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 8453–8474. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.S. Global and regional snow cover decline: 2000–2022. Climate 2023, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, B.D.; Wilson, A.M.; Wake, C.P.; Huntington, T.G. Are there spurious temperature trends in the United States Climate Division database? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menne, M.J.; Williams, C.N., Jr.; Palecki, M.A. On the reliability of the US surface temperature record. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115, D11108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods; Griffin: London, UK, 1975; ISBN 9780852641996. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric Tests Against Trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H.; Marofi, S.; Aeini, A.; Talaee, P.H.; Mohammadi, K. Trend analysis of reference evapotranspiration in the western half of Iran. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2011, 151, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandersson, H.A. A homogeneity test applied to precipitation data. J. Climatol. 1986, 6, 661–675. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandersson, H.; Moberg, A. Homogenization of Swedish Temperature Data Part I: Homogeneity Test for Linear Trends. Int. J. Climatol. 1997, 17, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, M.N.; Ouarda, T.B. On the critical values of the standard normal homogeneity test (SNHT). Int. J. Climatol. A J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2007, 27, 681–687. [Google Scholar]

- Elagib, N.A.; Mansell, M.G. Recent trends and anomalies in mean seasonal and annual temperatures over Sudan. J. Arid. Environ. 2000, 45, 263–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, M.; Doherty, R.; Ngara, T.; New, M.; Lister, D. African climate change: 1900–2100. Clim. Res. 2001, 17, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runkle, J.; Kunkel, K.E.; Easterling, D.; Stewart, B.C.; Champion, S.; Stevens, L.; Frankson, R.; Sweet, W. State Climate Summaries: Rhode Island; NOAA Technical Report NESDIS 149-RI; NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information: Asheville, NC, USA, 2017; 4p. [Google Scholar]

- Gille, S.T. Decadal-scale temperature trends in the Southern Hemisphere ocean. J. Clim. 2008, 21, 4749–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.S.; Krishnamurti, T.N.; Pattnaik, S.; Pai, D.S. Decadal surface temperature trends in India based on a new high-resolution data set. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenssen, N.; Schmidt, G.A.; Hendrickson, M.; Jacobs, P.; Menne, M.; Ruedy, R. A GISTEMPv4 observational uncertainty ensemble. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD040179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Ruedy, R.; Glascoe, J.; Sato, M. GISS analysis of surface temperature change. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1999, 104, 30997–31022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GISTEMP Team. GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP); Version 4; NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies: Columbia University Earth Institute: New York, NY, USA. Available online: https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Wan, Z. Collection-6 MODIS Land Surface Temperature Products Users’ Guide. ERI. Santa Barbara: University of California. 2013. Available online: https://icess.eri.ucsb.edu/modis/LstUsrGuide/MODIS_LST_products_Users_guide_C6.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Wan, Z. New Refinements and Validation of the Collection-6 MODIS Land-surface Temperature/emissivity Product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, C.; Caselles, V.; Galve, J.M.; Valor, E.; Niclos, R.; Sánchez, J.M.; Rivas, R. Ground measurements for the validation of land surface temperatures derived from AATSR and MODIS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 97, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adão, F.; Fraga, H.; Fonseca, A.; Malheiro, A.C.; Santos, J.A. The relationship between land surface temperature and air temperature in the Douro Demarcated Region, Portugal. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Tang, B.H.; Wu, H.; Ren, H.; Yan, G.; Wan, Z.; Trigo, I.F.; Sobrino, J.A. Satellite-derived land surface temperature: Current status and perspectives. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 131, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark Labs. TerrSet liberaGIS, Version 20.04; Clark University: Worcester, MA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.clarku.edu/centers/geospatial-analytics/terrset/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Wang, Y.R.; Hessen, D.O.; Samset, B.H.; Stordal, F. Evaluating global and regional land warming trends in the past decades with both MODIS and ERA5-Land land surface temperature data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 280, 113181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriou, D.; Kiachidis, K.; Kalmintzis, G.; Kalea, A.; Bantasis, C.; Koumadoraki, P.; Spathara, M.E.; Tsolaki, A.; Tzampazidou, M.I.; Gemitzi, A. Determination of annual and seasonal daytime and nighttime trends of MODIS LST over Greece-climate change implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Ma, M.; Wang, X.; Geng, L.; Tan, J.; Shi, J. 2014. Evaluation of MODIS LST Products Using Longwave Radiation Ground Measurements in the Northern Arid Region of China. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 11494–11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, G.A.; Hall, D.K.; Román, M.O. MODIS Snow Products User Guide for Collection. 2019. Available online: https://modis-snow-ice.gsfc.nasa.gov/?c=userguides (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Frei, A.; Tedesco, M.; Lee, S.; Foster, J.; Hall, D.K.; Kelly, R.; Robinson, D.A. A review of global satellite-derived snow products. Adv. Space Res. 2012, 50, 1007–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, T.; Dumont, M.; Mura, M.D.; Sirguey, P.; Gascoin, S.; Dedieu, J.P.; Chanussot, J. An assessment of existing methodologies to retrieve snow cover fraction from MODIS data. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, K.R.; Houser, P.R.; De Lannoy, G.J. Evaluation of the MODIS snow cover fraction product. Hydrol. Process. 2014, 28, 980–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, M.; Pulliainen, J.; Metsämäki, S.; Kontu, A.; Suokanerva, H. The behaviour of snow and snow-free surface reflectance in boreal forests: Implications to the performance of snow covered area monitoring. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Miao, X.; Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Qiu, B.; Ge, J.; Guo, W. Dynamic identification of snow phenology in the Northern Hemisphere. Cryosphere 2025, 19, 2733–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, H. Distribution and attribution of terrestrial snow cover phenology changes over the Northern Hemisphere during 2001–2020. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarenistanak, M.; Dhorde, A.G.; Kripalani, R.H.; Dhorde, A.A. Trends and projections of temperature, precipitation, and snow cover during snow cover-observed period over southwestern Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2015, 122, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Xu, L. MODIS/Terra observed snow cover over the Tibet Plateau: Distribution, variation and possible connection with the East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM). Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2009, 97, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.K.; Riggs, G.A.; Salomonson, V.V.; DiGirolamo, N.E.; Bayr, K.J. MODIS Snow-cover Products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.K.; Riggs, G.A. Accuracy Assessment of the MODIS Snow Products. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 1534–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roessler, S.; Dietz, A.J. Development of Global Snow Cover—Trends from 23 Years of Global SnowPack. Earth 2022, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.O. Statistical Methods for Environmental Pollution Monitoring; Van Nostrand Reinhold Company Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Helsel, D.R.; Hirsch, R.M. Statistical Methods in Water Resources; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Subash, N.; Sikka, A.K.; Ram Mohan, H.S. An investigation into observational characteristics of rainfall and temperature in Central Northeast India—A historical perspective 1889–2008. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2011, 103, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.M.; Santos, C.A.; Moreira, M.; Corte-Real, J.; Silva, V.C.; Medeiros, I.C. Rainfall and river flow trends using Mann–Kendall and Sen’s slope estimator statistical tests in the Cobres River basin. Nat. Hazards 2015, 77, 1205–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déry, S.J.; Brown, R.D. Recent Northern Hemisphere snow cover extent trends and implications for the snow-albedo feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwed, M.; Pińskwar, I.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Graczyk, D.; Mezghani, A. Changes of snow cover in Poland. Acta Geophys. 2017, 65, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Review article digital change detection techniques using remotely-sensed data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1989, 10, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafat, S. Land Surface Temperature Change between Coastal and Inlands Areas: A Case Study from the Persian Gulf. Northeast. Geogr. 2022, 13, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, J.; Holden, N.M.; Connolly, J.; Seaquist, J.W.; Ward, S.M. Detecting recent disturbance on Montane blanket bogs in the Wicklow Mountains, Ireland using the MODIS enhanced vegetation index. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 32, 2377–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, Z.L. Scale issues in remote sensing: A review on analysis, processing and modeling. Sensors 2009, 9, 1768–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aplin, P. On scales and dynamics in observing the environment. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 27, 2123–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Dube, O.P.; Solecki, W.; Aragón-Durand, F.; Cramer, W.; Humphreys, S.; Kainuma, M. Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 C; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 677, p. 393. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, D.; Wang, G.; Ahmed, K.F. Hydrological changes in the US Northeast using the Connecticut River Basin as a case study: Part 2. Projections of the future. Glob. Planet. Change 2015, 133, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake Champlain Basin Program. Climate Data Trends. Available online: https://www.lcbp.org/our-goals/clean-water/climate-change-impacts/climate-data-trends/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Giorgi, F. Climate change hot-spots. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L08707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P.; Scarascia, L. The relation between climate change in the Mediterranean region and global warming. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.; He, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Pang, H.; Gu, J. Regional structure of global warming across China during the twentieth century. Clim. Res. 2004, 27, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.B.; Tignor, M.; Miller, H.L. (Eds.) Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen, M.; Karpechko, A.Y.; Lipponen, A.; Nordling, K.; Hyvärinen, O.; Ruosteenoja, K.; Vihma, T.; Laaksonen, A. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.C.; Boeke, R.C.; Boisvert, L.N.; Feldl, N.; Henry, M.; Huang, Y.; Langen, P.L.; Liu, W.; Pithan, F.; Sejas, S.A.; et al. Process drivers, inter-model spread, and the path forward: A review of amplified Arctic warming. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 9, 758361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twardosz, R.; Walanus, A.; Guzik, I. Warming in Europe: Recent trends in annual and seasonal temperatures. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2021, 178, 4021–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yuan, X.; Jing, C.; Hamdi, R.; Ochege, F.U.; Dong, P.; Shao, Y.; Qin, X. The decreased cloud cover dominated the rapid spring temperature rise in arid Central Asia over the period 1980–2014. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL107523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittis, G.; Almazroui, M.; Alpert, P.; Ciais, P.; Cramer, W.; Dahdal, Y.; Fnais, M.; Francis, D.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Howari, F.; et al. Climate change and weather extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2021RG000762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuebbles, D.J.; Fahey, D.W.; Hibbard, K.A.; Dokken, D.J.; Stewart, B.C.; Maycock, T.K. (Eds.) 2017: Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment; U.S. Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume I, 470p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegerl, G.C.; Brönnimann, S.; Cowan, T.; Friedman, A.R.; Hawkins, E.; Iles, C.; Müller, W.; Schurer, A.; Undorf, S. Causes of climate change over the historical record. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 123006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, L.J.; Highwood, E.J.; Dunstone, N.J. The influence of anthropogenic aerosol on multi-decadal variations of historical global climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 024033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fang, G.; Duan, W.; Li, B.; Li, Z.; Hao, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X. The dominant warming season shifted from winter to spring in the arid region of Northwest China. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupigny-Giroux, L.A.L.; Mecray, E.L.; Lemcke-Stampone, M.D.; Hodgkins, G.; Lentz, E.; Mills, K.E.; Lane, E.D.; Miller, R.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Solecki, W.D.; et al. Northeast; US Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 669–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Guo, Y.; Xia, H.; Liu, X.; Song, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y. Increase asymmetric warming rates between daytime and nighttime temperatures over global land during recent decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL112832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, T.G.; Hodgkins, G.A.; Keim, B.D.; Dudley, R.W. Changes in the proportion of precipitation occurring as snow in New England (1949–2000). J. Clim. 2004, 17, 2626–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Bradley, R.S. Snow occurrence changes over the central and eastern United States under future warming scenarios. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.R.; Zwiers, F.W.; Gillett, N.P. Attribution of the spring snow cover extent decline in the Northern Hemisphere, Eurasia and North America to anthropogenic influence. Clim. Change 2016, 136, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakowski, E.A.; Contosta, A.R.; Grogan, D.; Nelson, S.J.; Garlick, S.; Casson, N. Future of winter in Northeastern North America: Climate indicators portray warming and snow loss that will impact ecosystems and communities. Northeast. Nat. 2022, 28, 180–207. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, K.S.; Winchell, T.S.; Livneh, B.; Molotch, N.P. Spatial variation of the rain–snow temperature threshold across the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Liu, G. The latitudinal dependence in the trend of snow event to precipitation event ratio. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, M. Impact of snow-albedo feedback termination on terrestrial surface climate at midhigh latitudes: Sensitivity experiments with an atmospheric general circulation model. Int. J. Clim. 2022, 42, 3838–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, A.R.; Mankin, J.S. Evidence of human influence on Northern Hemisphere snow loss. Nature 2024, 625, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkins, G.A.; Dudley, R.W. Changes in late-winter snowpack depth, water equivalent, and density in Maine, 1926–2004. Hydrol. Process. Int. J. 2006, 20, 741–751. [Google Scholar]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I.; et al. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). The state of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere based on global observations through 2024. In Greenhouse Gas Bulletin No. 21; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; ISSN 2078-0796. [Google Scholar]

- Jutras, M.; Dufour, C.O.; Mucci, A.; Talbot, L.C. Large-scale control of the retroflection of the Labrador Current. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2623. [Google Scholar]

- Smeed, D.A.; Josey, S.A.; Beaulieu, C.; Johns, W.E.; Moat, B.I.; Frajka-Williams, E.; Rayner, D.; Meinen, C.S.; Baringer, M.O.; Bryden, H.L.; et al. The North Atlantic Ocean is in a state of reduced overturning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershing, A.J.; Alexander, M.A.; Hernandez, C.M.; Kerr, L.A.; Le Bris, A.; Mills, K.E.; Nye, J.A.; Record, N.R.; Scannell, H.A.; Scott, J.D.; et al. Slow adaptation in the face of rapid warming leads to collapse of the Gulf of Maine cod fishery. Science 2015, 350, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Delworth, T.L.; Koul, V.; Ross, A.; Stock, C.; Yang, X.; Zeng, F.; Wittenberg, A.; Zhao, J.; Gu, Q.; et al. Skillful multiyear prediction of flood frequency along the US Northeast Coast using a high-resolution modeling system. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Yang, Y. Spring snow-albedo feedback from satellite observation, reanalysis and model simulations over the Northern Hemisphere. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2022, 65, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, A.; Catalano, F.; De Felice, M.; Van den Hurk, B.; Balsamo, G. Varying snow and vegetation signatures of surface-albedo feedback on the Northern Hemisphere land warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 034023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackeray, C.W.; Fletcher, C.G. Snow albedo feedback: Current knowledge, importance, outstanding issues and future directions. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2016, 40, 392–408. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, R.K.; Pretis, F. An empirical estimate for the snow albedo feedback effect. Clim. Change 2023, 176, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control, Regional Health Effects—Northeast. 3 June 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/climate-health/php/regions/northeast.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Barnes, C.S. Impact of climate change on pollen and respiratory disease. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018, 18, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkishe, A.; Raghavan, R.K.; Peterson, A.T. Likely geographic distributional shifts among medically important tick species and tick-associated diseases under climate change in North America: A review. Insects 2021, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S. Climate change and mental health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2021, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, K.; Licker, R.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Declet-Barreto, J. Increased frequency of and population exposure to extreme heat index days in the United States during the 21st century. Environ. Res. Commun. 2019, 1, 075002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lin, Z.; Beardsley, R.C.; Shyka, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Qi, J.; Lin, H.; Xu, D. Impacts of sea level rise on future storm-induced coastal inundations over Massachusetts coast. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, J.F.; Narinesingh, V.; Towey, K.L.; Jeyaratnam, J. Storm surge, blocking, and cyclones: A compound hazards analysis for the northeast United States. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2021, 60, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, T.L.; Lin, N. Climate change impacts to the coastal flood hazard in the northeastern United States. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2022, 36, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runkle, J.; Kunkel, K.E.; Frankson, R.; Easterling, D.R.; DeGaetano, A.T.; Stewart, B.C.; Sweet, W.; Spaccio, J. Massachusetts State Climate Summary 2022 (NOAA Technical Report NESDIS 150-MA). NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. 2022. Available online: https://statesummaries.ncics.org/chapter/ma/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Fant, C.; Gentile, L.E.; Herold, N.; Kunkle, H.; Kerrich, Z.; Neumann, J.; Martinich, J. Valuation of long-term coastal wetland changes in the U.S. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 226, 106248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Westen, R.M.; Kliphuis, M.; Dijkstra, H.A. Physics-based early warning signal shows that AMOC is on tipping course. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Patricola, C.M.; Winter, J.M.; Osterberg, E.C.; Mankin, J.S. 2021: Rise in Northeast US extreme precipitation caused by Atlantic variability and climate change. Weather. Clim. Extrem. 2021, 33, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakauer, N.Y.; Lakhankar, T.; Hudson, D. Trends in drought over the northeast United States. Water 2019, 11, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, D.W.; DeGaetano, A.T.; Peck, G.M.; Carey, M.; Ziska, L.H.; Lea-Cox, J.; Kemanian, A.R.; Hoffmann, M.P.; Hollinger, D.Y. Unique challenges and opportunities for northeastern US crop production in a changing climate. Clim. Change 2018, 146, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.A.; Skific, N.; Vavrus, S.J.; Cohen, J. Measuring “weather whiplash” events in North America: A new large-scale regime approach. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2022JD036717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L.A.; Griffin, R.; Young, T.; Fuller, E.; Martin, K.S.; Pinsky, M.L. Shifting habitats expose fishing communities to risk under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershing, A.J.; Alexander, M.A.; Brady, D.C.; Brickman, D.; Curchitser, E.N.; Diamond, A.W.; McClenachan, L.; Mills, K.E.; Nichols, O.C.; Pendleton, D.E.; et al. Climate impacts on the Gulf of Maine ecosystem: A review of observed and expected changes in 2050 from rising temperatures. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2021, 9, 00076. [Google Scholar]

- Northeast Fisheries Science Center, United States (NEFSC). State of the Ecosystem 2022: New England; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Washington, DC, USA; National Marine Fisheries Service: Silver Spring, MD, USA; Northeast Fisheries Science Center: Woods Hole, MA, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Foster, D.; Johnson, E.E.; Hall, B.R.; Leibowitz, J.; Thompson, E.H.; Donahue, B.; Faison, E.K.; Sayen, J.; Publicover, D.; Sferra, N.; et al. Wildlands in New England. Past, Present, and Future; Harvard Forest Paper 36; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, K.L.M.; Wang, D.; Waite, C.; Scherbatskoy, T. Snow removal and ambient air temperature effects on forest soil temperatures in northern Vermont. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2003, 67, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, K.J.; Aoki, C.F.; Arango-Velez, A.; Cancelliere, J.; D’Amato, A.W.; DiGirolomo, M.F.; Rabaglia, R.J. Expansion of southern pine beetle into northeastern forests: Management and impact of a primary bark beetle in a new region. J. For. 2018, 116, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L.; Ollinger, S.V.; Flerchinger, G.N.; Wicklein, H.; Hayhoe, K.; Bailey, A.S. Past and projected future changes in snowpack and soil frost at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, New Hampshire, USA. Hydrol. Process. 2010, 24, 2465–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, E.P.; Cinquino, E. The climatological rise in winter temperature-and dewpoint-based thaw events and their impact on snow depth on Mount Washington, New Hampshire. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2021, 60, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, J.E.; Price, J.; Chinowsky, P.; Wright, L.; Ludwig, L.; Streeter, R.; Jones, R.; Smith, J.B.; Perkins, W.; Jantarasami, L.; et al. Climate change risks to US infrastructure: Impacts on roads, bridges, coastal development, and urban drainage. Clim. Change 2015, 131, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Dawson, J.; Jones, B. Climate change vulnerability of the US Northeast winter recreation–tourism sector. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2008, 13, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contosta, A.R.; Casson, N.J.; Garlick, S.; Nelson, S.J.; Ayres, M.P.; Burakowski, E.A.; Campbell, J.; Creed, I.; Eimers, C.; Evans, C.; et al. Northern forest winters have lost cold, snowy conditions that are important for ecosystems and human communities. Ecol. Appl. 2019, 29, e01974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, S.J.; Elliott, R.; Lehtonen, T.K. Climate change and insurance. Econ. Soc. 2021, 50, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, M. An inconvenient cost: The effects of climate change on municipal bonds. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 135, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautner, Z.; Van Lent, L.; Vilkov, G.; Zhang, R. Pricing climate change exposure. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 7540–7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, A.; Reidmiller, D. 2023: Status of State-Level Climate Action in the Northeast Region: A Technical Input to the Fifth National Climate Assessment; Gulf of Maine Research Institute: Portland, ME, USA, 2023; Available online: https://gmri.org/commitments/strategic-initiatives/climate-center/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Whitehead, J.C.; Mecray, E.L.; Lane, E.D.; Kerr, L.; Finucane, M.L.; Reidmiller, D.R.; Bove, M.C.; Montalto, F.A.; O’Rourke, S.; Zarrilli, D.A.; et al. Chapter 21. Northeast. In Fifth National Climate Assessment; Crimmins, A.R., Avery, C.W., Easterling, D.R., Kunkel, K.E., Stewart, B.C., Maycock, T.K., Eds.; U.S. Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita-Emlinger, A. Challenges to address climate adaptation actions in coastal New England—Insights from a web survey. Rev. Geográfica América Cent. 2018, 3, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.S.; Rao, S.; Dorey, K. Monitoring the erosion and accretion of a human-built living shoreline with drone technology. Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, N.; Young, S.S.; Nafa, F.; Waddington, G. Impact of Solar Farm Expansion on Forest Cover in Massachusetts: An Analysis Using Artificial Intelligence and Remote Sensing. Prof. Geogr. 2025, 77, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi’kmaq Nation—Thirteen Moons: Climate Change Adaptation Plan. Mi’kmaq Nation. Available online: https://www.usetinc.org/departments/oerm/climate-change/tribal-climate-planning-documents/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

| State | Annual a | Spring b | Summer c | Fall d | Winter e | Over 1.5 °C f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | ||||||

| (4 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 1.48 ** | 1.40 * | 0.30 | 0.89 | 2.99 ** | 10/15 |

| Average | 2.46 ** | 1.30 * | 1.72 * | 1.95 ** | 4.48 ** | |

| Minimum | 3.69 ** | 2.38 ** | 3.60 ** | 2.92 ** | 5.24 ** | |

| Maine | ||||||

| (12 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 1.73 ** | 1.10 | 1.59 * | 0.62 | 3.22 ** | 11/15 |

| Average | 2.63 ** | 1.48 * | 2.02 ** | 2.18 ** | 4.38 ** | |

| Minimum | 3.07 ** | 1.49 * | 2.40 ** | 2.44 ** | 5.41 ** | |

| Massachusetts | ||||||

| (12 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 2.62 ** | 1.70 * | 2.30 * | 2.23 ** | 3.84 ** | 14/15 |

| Average | 2.75 ** | 1.64 ** | 2.57 ** | 2.24 ** | 4.26 ** | |

| Minimum | 2.92 ** | 1.28 * | 2.78 ** | 2.33 ** | 5.03 ** | |

| New Hampshire | ||||||

| (5 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 1.88 ** | 1.17 | 1.55 * | 1.37 * | 2.97 ** | 12/15 |

| Average | 2.41 ** | 1.36 * | 2.03 ** | 1.91 ** | 3.86 ** | |

| Minimum | 2.95 ** | 1.57 * | 2.63 ** | 2.34 ** | 4.76 ** | |

| Rhode Island | ||||||

| (3 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 2.73 ** | 1.95 ** | 2.00 * | 2.51 ** | 4.41 ** | 13/15 |

| Average | 2.38 ** | 1.42 * | 2.12 ** | 1.95 ** | 3.80 ** | |

| Minimum | 1.89 ** | 0.89 | 1.93 ** | 1.68 * | 3.30 ** | |

| Vermont | ||||||

| (8 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 2.55 ** | 1.91 * | 2.14 ** | 2.31 ** | 3.38 ** | 13/15 |

| Average | 2.55 ** | 1.40 | 2.07 ** | 2.21 ** | 4.01 ** | |

| Minimum | 2.65 ** | 0.73 | 1.89 ** | 2.47 ** | 5.53 ** | |

| New England | ||||||

| (44 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 2.17 ** | 1.54 * | 1.65 * | 1.66 ** | 3.42 ** | 13/15 |

| Average | 2.53 ** | 1.43 * | 2.09 ** | 2.07 ** | 4.13 ** | |

| Minimum | 2.77 ** | 1.33 ** | 2.50 ** | 2.21 ** | 4.74 ** |

| State | Annual a | Spring b | Summer c | Fall d | Winter e | Significance f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | ||||||

| (4 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 0.60 | 1.01 | 0.36 | −0.35 | 1.00 | 3/15 |

| Average | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.15 | −0.10 | 0.66 | |

| Minimum | 1.04 *** | 1.03 ** | 1.38 *** | 0.43 | 0.91 | |

| Maine | ||||||

| (12 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 0.55 ** | 1.14 * | 0.33 | −0.58 | 1.24 | 5/15 |

| Average | 1.04 *** | 1.35 *** | 0.46 | 0.56 | 1.72 * | |

| Minimum | 1.07 *** | 1.18 ** | 0.60 | 0.40 | 2.03 * | |

| Massachusetts | ||||||

| (12 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 0.77 *** | 1.11 * | 0.19 | 0.59 | 1.01 | 7/15 |

| Average | 0.89 *** | 1.05 ** | 0.46 | 0.53 | 1.30 * | |

| Minimum | 1.05 *** | 0.71 ** | 0.78 ** | 0.65 * | 1.83 ** | |

| New Hampshire | ||||||

| (5 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 0.46 | 0.85 | −0.29 | 0.10 | 0.98 | 5/15 |

| Average | 0.94 *** | 1.19 ** | 0.54 | 0.44 | 1.38 * | |

| Minimum | 1.22 *** | 1.38 *** | 1.12 *** | 0.40 | 1.70 * | |

| Rhode Island | ||||||

| (3 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 0.65 | 0.87 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 1.29 ** | 3/15 |

| Average | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.41 | 0.17 | 1.01 | |

| Minimum | 0.64 ** | 0.77 * | 0.67 ** | −0.15 | 1.28 * | |

| Vermont | ||||||

| (8 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 0.77 ** | 1.40 ** | 0.30 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 5/15 |

| Average | 0.95 *** | 1.28 * | 0.63 * | 0.57 * | 1.20 | |

| Minimum | 0.88 *** | 1.11 ** | 0.79 * | 0.68 | 0.77 | |

| New England | ||||||

| (44 USHCN stations) | ||||||

| Maximum | 0.63 * | 1.06 * | 0.15 | 0.12 | 1.04 * | 5/15 |

| Average | 0.79 *** | 1.00 * | 0.44 ** | 0.36 | 1.21 * | |

| Minimum | 0.90 *** | 0.97 ** | 0.81 *** | 0.33 | 1.27 * |

| Area | Minimum | Average | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT | 66% | 55% | 41% |

| RI | 87% | 72% | 60% |

| MA | 79% | 64% | 55% |

| ME | 91% | 84% | 67% |

| NH | 84% | 81% | 51% |

| VT | 80% | 80% | 70% |

| NE | 80% | 75% | 68% |

| Region | Day/Night | Spring a | Summer b | Fall c | Winter d | Annual e | USHCN f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | Day | 0.370 | 0.982 | 1.224 | 1.600 * | 0.457 | −0.07 |

| Night | 1.114 | 1.283 * | 1.458 * | 1.749 ** | 1.429 ** | 1.80 * | |

| Rhode Island | Day | 0.218 | 0.809 | 0.847 | 1.270 * | 0.248 | 1.39 |

| Night | 1.238 | 1.307 * | 1.462 * | 1.635 ** | 1.297 ** | 0.95 | |

| Massachusetts | Day | 0.621 | 0.899 | 1.208 | 1.536 | 0.749 | 0.92 * |

| Night | 1.367 | 1.280 * | 1.624 * | 1.792 ** | 1.454 ** | 1.38 * | |

| Maine | Day | 0.813 | 0.917 | 0.883 | 0.929 | 0.586 | 0.88 |

| Night | 1.595 * | 1.483 * | 1.445 * | 2.129 ** | 1.694 ** | 2.29 ** | |

| New Hampshire | Day | 0.583 | 0.786 | 1.188 | 1.215 | 0.558 | 0.81 |

| Night | 1.445 | 1.103 | 1.553 ** | 1.706 ** | 1.498 ** | 1.96 * | |

| Vermont | Day | 0.971 | 0.733 | 1.171 | 1.638 | 0.702 | 1.22 * |

| Night | 1.679 * | 1.061 * | 1.615 ** | 1.659 ** | 1.529 ** | 1.57 * | |

| New England | Day | 0.738 | 0.873 | 1.030 | 1.199 * | 0.600 | 0.86 * |

| Night | 1.52 ** | 1.327 ** | 1.510 ** | 1.911 ** | 1.599 ** | 1.66 ** |

| Region | Spring | Fall | Winter | Annual |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT-2000-04 a | 13.48 | 5.83 | 62.27 | 81.59 |

| CT-2020-24 a | 7.25 | 2.00 | 42.04 | 51.28 |

| Difference b | 6.24 | 3.83 | 20.23 | 30.30 |

| % Change c | −46% | −66% | −33% | −37% |

| RI-2000-04 a | 13.79 | 7.51 | 57.71 | 79.00 |

| RI-2020-24 a | 5.40 | 2.49 | 39.02 | 46.92 |

| Difference b | 8.39 | 5.01 | 18.68 | 32.09 |

| % Change c | −61% | −67% | −32% | −41% |

| MA-2000-04 a | 19.91 | 7.76 | 69.78 | 97.44 |

| MA-2020-24 a | 11.05 | 3.97 | 51.34 | 66.36 |

| Difference b | 8.86 | 3.79 | 18.44 | 31.09 |

| % Change c | −45% | −49% | −26% | −32% |

| ME-2000-04 a | 44.38 | 17.37 | 85.93 | 147.68 |

| ME-2020-24 a | 35.34 | 14.41 | 81.49 | 131.24 |

| Difference b | 9.04 | 2.96 | 4.45 | 16.44 |

| % Change c | −20% | −17% | −5% | −11% |

| NH-2000-04 a | 35.00 | 11.73 | 82.21 | 128.93 |

| NH-2020-24 a | 26.06 | 8.51 | 75.64 | 110.21 |

| Difference b | 8.94 | 3.22 | 6.57 | 18.73 |

| % Change c | −26% | −28% | −8% | −15% |

| VT-2000-04 a | 39.35 | 12.34 | 84.58 | 136.27 |

| VT-2020-24 a | 29.38 | 9.28 | 79.16 | 117.82 |

| Difference b | 9.97 | 3.06 | 5.42 | 18.45 |

| % Change c | −25% | −25% | −6% | −14% |

| NE-2000-04 a | 36.74 | 13.69 | 81.06 | 131.49 |

| NE-2020-24 a | 27.70 | 7.57 | 73.10 | 108.37 |

| Difference b | 9.04 | 6.12 | 7.96 | 23.12 |

| % Change c | −25% | −45% | −10% | −18% |

| CT | MA | ME | NH | RI | VT | NE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–2004 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2005–2009 | −1.87 | −4.22 | −0.82 | −2.22 | −2.80 | −3.48 | −1.92 |

| 2010–2014 | 0.48 | 1.04 | 2.01 | 1.54 | 0.02 | 1.85 | 1.66 |

| 2015–2019 | −5.72 | −4.08 | −0.21 | −2.59 | −4.05 | −3.02 | −1.98 |

| 2020–2024 b | −5.75 | −5.87 | −7.74 | −4.86 | −6.53 | −2.68 | −6.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Young, S.S.; Young, J.S. Decreasing Snow Cover and Increasing Temperatures Are Accelerating in New England, USA, with Long-Term Implications. Climate 2025, 13, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120246

Young SS, Young JS. Decreasing Snow Cover and Increasing Temperatures Are Accelerating in New England, USA, with Long-Term Implications. Climate. 2025; 13(12):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120246

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoung, Stephen S., and Joshua S. Young. 2025. "Decreasing Snow Cover and Increasing Temperatures Are Accelerating in New England, USA, with Long-Term Implications" Climate 13, no. 12: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120246

APA StyleYoung, S. S., & Young, J. S. (2025). Decreasing Snow Cover and Increasing Temperatures Are Accelerating in New England, USA, with Long-Term Implications. Climate, 13(12), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120246