Adaptation and Coping Strategies of Women to Reduce Food Insecurity in an Era of Climate Change: A Case of Chireya District, Zimbabwe

Abstract

1. Introduction

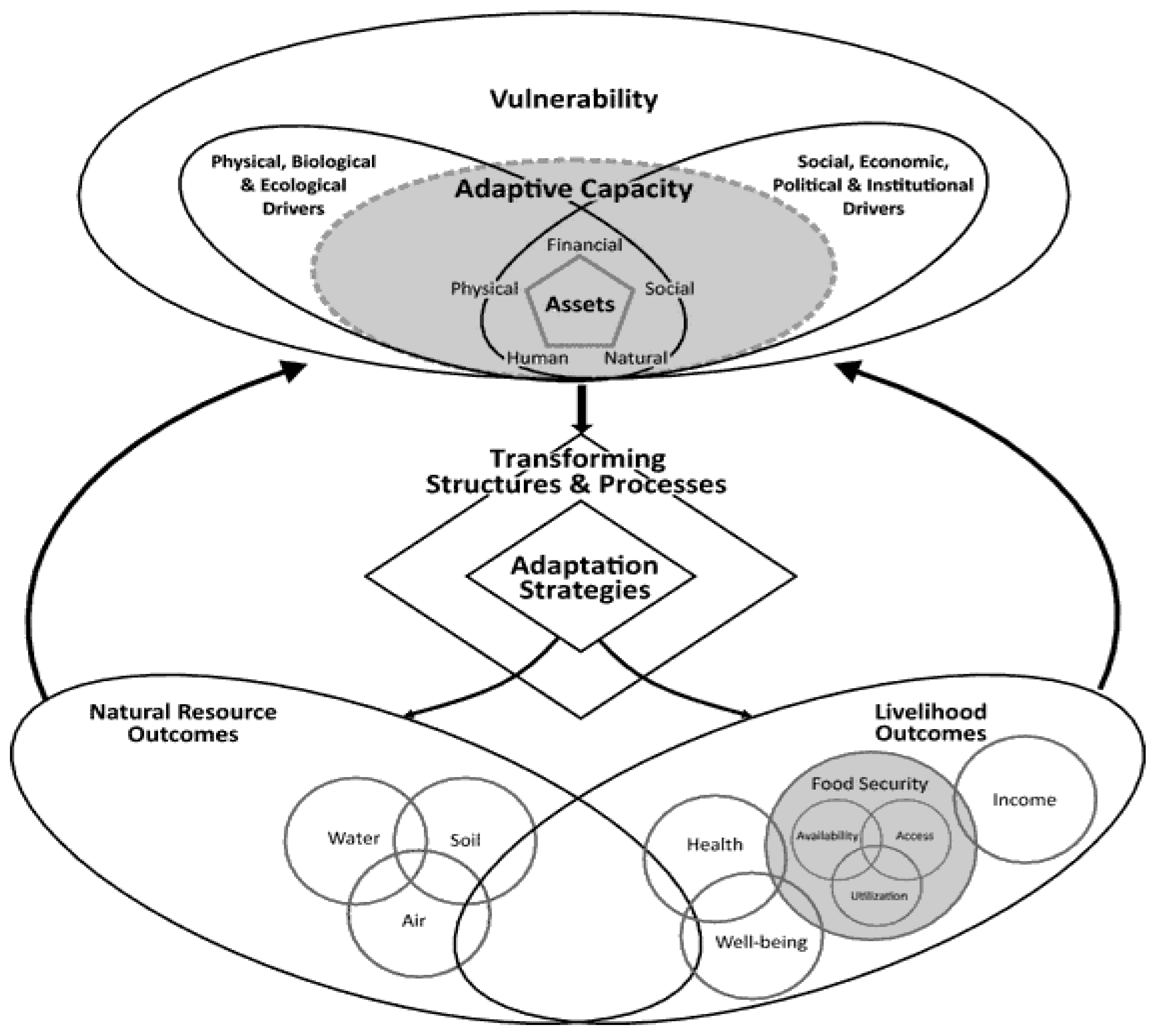

Framework for Climate Change, Food Security, and Sustaining Livelihoods

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Data Presentation and Analysis

3.1.1. Respondents’ Gender Distribution

3.1.2. Respondent Ages

3.1.3. Respondents’ Number of Years in Farming Experience

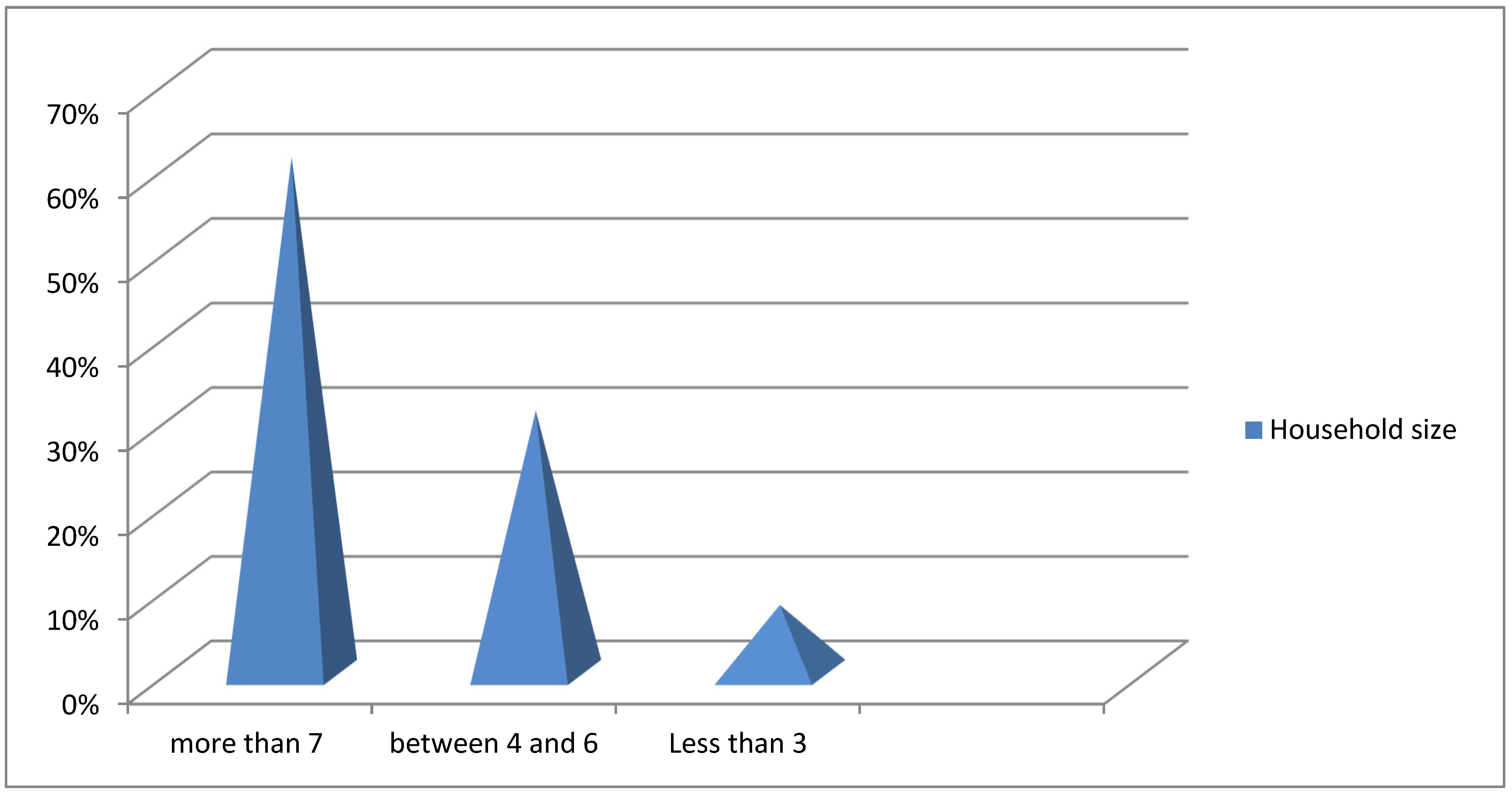

3.2. Family Size of the Residents

3.3. The Effects of Climate Change on Livelihoods

3.4. Coping and Effectiveness of Strategies to Reduce Food Insecurity

3.5. Effectiveness of the Coping Strategies

3.6. Stakeholders Assisting the Communities to Cope with the Effects of Food Insecurity

- Changing planting dates;

- Switching to early maturity drought-resistant crops;

- Crop rotation and diversification;

- Increasing the amount of land under cultivation;

- Digging the wells along the flood plains;

- Gardening (growing vegetables) to supplement diet;

- Water harvesting/dam construction;

- Income generating projects (IGPs) for both men and women.

3.7. Implications of the Findings

- The need for awareness among farmers regarding the harmful effects of environmental practices such as deforestation, veld fires, stream bank cultivation, and overuse of inorganic chemicals is emphasized. Government institutions responsible for environmental management should actively engage with rural communities to provide this awareness. Additionally, there is a call for the integration and implementation of a comprehensive framework for capacity building. This involves collaboration among government bodies such as the Ministry of Agriculture, Environmental Management Agency, and Local Government to educate farmers about the adverse impacts of environmental degradation.

- The Agriculture Research and Extension Services (Agritex) requires improvement to provide guidance on various drought-resistant crops, such as sorghum, and animals like donkeys. Additionally, there is a necessity to educate farmers about the significance of organic fertilizers and equip them with skills to adapt to fluctuations in precipitation and temperature. Furthermore, integrating indigenous knowledge systems is crucial for addressing climate challenges effectively.

- Government institutions, in collaboration with local communities, should implement improved water harvesting methods. These initiatives would assist communities in accessing domestic and drinking water for both humans and animals in the aftermath of rainfall. Additionally, this harvested water could be utilized for gardening purposes, thereby enhancing food supplies and dietary diversity.

- Early warning systems utilizing efficient information and communication technology are essential to swiftly distribute information to rural communities at the village level. Additionally, it is advisable to provide comprehensive training to farmers on managing various diseases.

- The Agriculture Research and Extension Services (Agritex) should promote the expansion and enhancement of non-farming income streams. This could involve implementing projects aimed at generating income, enhancing skills, and improving living standards for many individuals, enabling households to better withstand the impacts of climate change.

- To combat livestock illnesses, it is imperative to enhance production capabilities swiftly to mitigate losses and enhance productivity. Increasing veterinary extension services and providing training to existing personnel are highly recommended actions to decrease livestock mortality rates and enhance production levels.

- The Ministry of Women’s Affairs, along with its partners, must raise awareness about the significance of empowering girls, and work towards diminishing instances of gender-based violence.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. In Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Chapter 24; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Mikhaylov, A.; Moiseev, N.; Aleshin, K.; Burkhardt, T. Global climate change and greenhouse effect. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, K.; Nhliziyo, M.; Madzivire, S.; Sithole, M.; Nyathi, D. Understanding climate smart agriculture and the resilience of smallholder farmers in Umguza district, Zimbabwe. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2021, 7, 1970425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanza, N.; Musakwa, W. Ecological and hydrological indicators of climate change observed by dryland communities of Malipati in Chiredzi, Zimbabwe. Diversity 2022, 14, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangarirai, W.; Marnani, C.; Rahmat, A. Analyzing the impact of community-based approaches on disaster preparedness to the risk of tropical cyclone induced flooding in Chimanimani district, Zimbabwe. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1173, 012070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govere, S.; Nyamangara, J.; Nyakatawa, E. Review: Climate change and the water footprint of wheat production in Zimbabwe. Water SA 2019, 45, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsa, M. Climate change and lessons from world indigenous minority communities. In Climate Change and Agriculture in Zimbabwe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mushore, T.D.; Mhizha, T.; Manjowe, M.; Mashawi, L.; Matandirotya, E.; Mashonjowa, E.; Mutasa, C.; Gwenzi, J.; Mushambi, G.T. Climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies for small holder farmers: A case of Nyang district in Zimbabwe. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 676495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waha, K.; Müller, C.; Bondeau, A.; Dietrich, J.P.; Kurukulasuriya, P.; Heinke, J.; Lotze-Campen, H. Adaptation to climate change through the choice of cropping system and sowing date in sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2012, 23, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujakhu, N.; Ranjitkar, S.; He, J.; Schmidt-Vogt, D.; Su, Y.; Xu, J. Assessing the livelihood vulnerability of rural indigenous households to climate changes in central Nepal, Himalaya. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, A.K. “The poor feel it the most”: The Antilles bishops, the poor, and climate change. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 80, 1155–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, K.H.; Sari, D.P.; Latifa, A. Sustainability of climate change issues in Indonesia: The voices of women’s NGOs. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1105, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlahla, S. Gender perspectives of the water, energy, land, and food security nexus in sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 719913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Exelle, B.; Riedl, A. Gender inequality and resource sharing: Evidence from rural Nicaragua. J. Dev. Perspect. 2018, 2, 62–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigabie, A.; Teferra, B.; Abe, A. Access and control of resources by rural women in north Shewa zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Res. World Agric. Econ. 2022, 3, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amporfu, E.; Grépin, K. Measuring and explaining changing patterns of inequality in institutional deliveries between urban and rural women in Ghana: A decomposition analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otu, J.; Anam, B. The role of women in food production and poverty reduction in rural communities in cross river state. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rahman, M.M.; Dana, L.; Moral, I.H.; Anjum, N.; Rahaman, M.S. Challenges of rural women entrepreneurs in Bangladesh to survive their family entrepreneurship: A narrative inquiry through storytelling. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2022, 13, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Gupta, A.; Agrawal, A.; Gandhi, A.; Gupta, M.; Das, M. Women and tobacco use: Discrepancy in the knowledge, belief and behavior towards tobacco consumption among urban and rural women in Chhattisgarh, central India. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 6365–6373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shukla, R.; Kanaan, M.; Siddiqi, K. Tobacco use among 1,310,716 women of reproductive age (15–49 years) in 42 low- and middle-income countries: Secondary data analysis from the 2010–2016 demographic and health surveys. SSRN Electron. J. 2021, 23, 2019–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füssel, H.M.; Kein, R. Climate change vulnerability assessments: An evolution of conceptual thinking. Clim. Chang. 2006, 75, 301–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füssel, H. Vulnerability: A generally applicable conceptual framework for climate change research. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007, 17, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongolo, M.; Dlamini, D.K. Small-scale livestock farming in developing areas of Swaziland and South Africa. AFRREV STECH An Int. J. Sci. Technol. Bahir Dar Ethiop. 2012, 1, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zenda, M.; Malan, P.J. The sustainability of small-scale sheep farming systems in the Northern Cape (Hantam Karoo), South Africa. S. Afr. J. Agric. Extension 2021, 49, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, R.; Colbourn, T.; Lauriola, P.; Leonardi, G.; Hajat, S.; Zeka, A. A critical analysis of the drivers of human migration patterns in the presence of climate change: A new conceptual model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z. A review of research on the dilemma of motherhood in contemporary China. In 2022 6th International Seminar on Education, Management and Social Sciences; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniw, M.; James, T.D.; Ruth Archer, C.; Römer, G.; Levin, S.; Compagnoni, A.; Che-Castaldo, J.; Bennett, J.M.; Mooney, A.; Childs, D.Z.; et al. The myriad of complex demographic responses of terrestrial mammals to climate change and gaps of knowledge: A global analysis. J. Anim. Ecol. 2021, 90, 1398–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertel, T.W.; Rosch, S. Climate change, agriculture, and poverty. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2010, 32, 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Anttila-Hughes, J. Characterizing the contribution of high temperatures to child undernourishment in sub-Saharan Africa. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abid, M.; Scheffran, J.; Schneider, U.A.; Ashfaq, M. Farmers’ perceptions of and adaptation strategies to climate change and their determinants: The case of Punjab province, Pakistan. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2015, 6, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Impact of relocation in response to climate change on farmers’ livelihood capital in minority areas: A case study of Yunnan province. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2023, 15, 790–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlophe-Ginindza, S.; Mpandeli, N.S. The role of small-scale farmers in ensuring food security in Africa. In Food Security in Africa; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challinor, A.J.; Wheeler, T.; Garforth, C.; Craufurd, P.; Kassam, A. Assessing the vulnerability of food crop systems in Africa to climate change. Clim. Chang. 2007, 83, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.F.; Rodriguez, A.V.C. Emerging advanced technologies to mitigate the impact of climate change in Africa. Plants 2020, 9, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickson, R.B.; Boateng, E. Climate change: A friend or foe to food security in Africa? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 24, 4387–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adepoju, A.O.; Obialo, A. Agricultural labour productivity growth and food insecurity transitions among maize farming households in rural Nigeria. Ekon. Poljopr. 2022, 69, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.K.; Schilizzi, S. The nexus between food security and livelihoods: A study on the determinants of food security in rural areas of Pakistan. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 327–337. [Google Scholar]

- Schnitter, R.; Berry, P. The climate change, food security and human health nexus in Canada: A framework to protect population health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; IDS Working Paper 72; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, D.; Drinkwater, M.; Rusinow, T.; Neefjes, K.; Wanmali, S.; Singh, N. Livelihoods Approaches Compared; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999.

- Murniati, K.; Mutolib, A. The impact of climate change on the household food security of upland rice farmers in Sidomulyo, Lampung province, Indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toimil, A.; Camus, P.; Losada, Í.J.; Cozannet, G.L.; Nicholls, R.J.; Idier, D.; Maspataud, A. Climate change-driven coastal erosion modelling in temperate sandy beaches: Methods and uncertainty treatment. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 202, 103110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houessou, M.D.; Cassee, A.; Sonneveld, B. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security in rural and urban settlements in benin: Do allotment gardens soften the blow? Sustainability 2021, 13, 7313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okesanya, O.J.; Alnaeem, K.F.H.; Hassan, H.K.; Oso, A.T.; Adigun, O.A.; Bouaddi, O.; Olaleke, N.O.; Kheir, S.G.M.; Haruna, U.A.; Shomuyiwa, D.O.; et al. The intersectional impact of climate change and gender inequalities in Africa. Public Health Chall. 2024, 3, e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.V.; Davis, M.D. Climate change and the epidemiology of selected tick-borne and mosquito-borne diseases: Update from the international society of dermatology climate change task force. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 56, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Suranny, L.E.; Gravitiani, E.; Rahardjo, M. Impact of climate change on the agriculture sector and its adaptation strategies. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1016, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidazada, M.; Cruz, A.M.; Yokomatsu, M. Vulnerability factors of Afghan rural women to disasters. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2019, 10, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, F. Climate change and violence against women: Study of a flood-affected population in the rural area of sindh, pakistan. Pak. J. Women Stud. Alam-E-Niswan 2020, 27, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretz, E.; Itaru, A.; Glas, M.; Waswa, L.; Jordan, I. Is responsive feeding difficult? a case study in teso south sub-county, kenya. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris-Fry, H.; Nur, H.; Shankar, B.; Zanello, G.; Srinivasan, C.; Kadiyala, S. The impact of gender equity in agriculture on nutritional status, diets, and household food security: A mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Global Health 2020, 5, e002173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridge, J. Barriers to accessing medical services: A review of economic and cultural factors. J. Health Econ. 2008, 15, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, W.; Seager, R.; Baethgen, W.E.; Cane, M.A.; You, L. Synchronous crop failures and climate-forced production variability. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, M.A.; Duguay, C.; Ost, K. Charting the evidence for climate change impacts on the global spread of malaria and dengue and adaptive responses: A scoping review of reviews. Glob. Health 2022, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- True, J. Gendered violence in natural disasters: Learning from New Orleans, Haiti and Christchurch. Aotearoa N. Z. Soc. Work 2016, 25, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, E.; Wilson, R. Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Below, T.B.; Mutabazi, K.D.; Kirschke, D.; Franke, C.; Sieber, S.; Siebert, R.; Tscherning, K. Can farmers’ adaptation to climate change be explained by socio-economic household-level variables? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2012, 22, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, H.; Skoufias, E. Testing Theories of Consumption Behaviour Using Information on Aggregate Shocks: Income Seasonality and Rainfall in Rural India. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1997, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochar, A. Explaining household vulnerability to idiosyncratic income shocks. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Morduch, J. Income smoothing and consumption smoothing. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoufias, E.; Rabassa, M.; Olivieri, S.; Brahmbhatt, M. The poverty impacts of climate Change. PREM Policy Brief 2011, 51, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

| Gender Distribution | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Women | 62 |

| Men | 33 |

| Village heads | 5 |

| Ages | |

| 50–60 | 58 |

| 61–70 | 40 |

| 75+ | 2 |

| Education level | |

| Never went to school | 3 |

| Finished primary education | 58 |

| Secondary education | 36 |

| Tertiary education | 3 |

| Farming experience in years | |

| 0–4 | 9 |

| 5–9 | 12 |

| 10–20 | 22 |

| 21 and above | 57 |

| Coping Strategy | Percentage of Women Using the Coping Strategy | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Selling items such as plows, harrows, and cultivators. | 100% | 60% |

| Altering the time of planting. | 90% | 80% |

| Selling domestic animals like cattle and goats, as well as domestic birds like chickens. | 90% | 65% |

| Borrowing from kins, friends, and from the chief. | 90% | 60% |

| Transitioning to drought-tolerant varieties of crops such as sorghum. | 88% | 75% |

| Informal employment. | 80% | 50% |

| Decreasing the frequency of daily meals. | 80% | 50% |

| Bartering pieces of land for grains. | 80% | 50% |

| Unlawful trade of firewood. | 72% | 35% |

| Buying on credit and paying after harvests or selling an asset. | 70% | 50% |

| Exchanging livestock and assets in return for crops. | 70% | 50% |

| Illegal mining activities. | 70% | 45% |

| Adding wild fruits to their diet as a supplement. | 70% | 30% |

| Depending on funding bodies or contributors. | 67% | 55% |

| Excavating deep wells alongside the flood plains. | 60% | 55% |

| Reducing the quantity and quality of meals. | 60% | 40% |

| Vending untamed fruits in rural hubs and urban areas. | 50% | 40% |

| Food for work and money for work programs. | 36% | 42% |

| Temporarily relocating children to more prosperous relatives, such as in-laws. | 26% | 20% |

| Consuming grains left aside as seeds. | 26% | 20% |

| Help from friends. | 20% | 20% |

| Arranging marriages for their daughters. | 12% | 10% |

| Stakeholder | Duties |

|---|---|

| Local Government |

|

| Agritex |

|

| Grain Marketing Board |

|

| Women affairs |

|

| NGOs | Food and money distribution during the period in food insecurity situations. |

| Social welfare |

|

| Environmental Management | Protect the environment from being exploited. They reported that it helped to mitigate veld fires; land degradation; siltation; deforestation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magwegwe, E.; Zivengwa, T.; Zenda, M. Adaptation and Coping Strategies of Women to Reduce Food Insecurity in an Era of Climate Change: A Case of Chireya District, Zimbabwe. Climate 2024, 12, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli12080126

Magwegwe E, Zivengwa T, Zenda M. Adaptation and Coping Strategies of Women to Reduce Food Insecurity in an Era of Climate Change: A Case of Chireya District, Zimbabwe. Climate. 2024; 12(8):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli12080126

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagwegwe, Everjoy, Taruberekerwa Zivengwa, and Mashford Zenda. 2024. "Adaptation and Coping Strategies of Women to Reduce Food Insecurity in an Era of Climate Change: A Case of Chireya District, Zimbabwe" Climate 12, no. 8: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli12080126

APA StyleMagwegwe, E., Zivengwa, T., & Zenda, M. (2024). Adaptation and Coping Strategies of Women to Reduce Food Insecurity in an Era of Climate Change: A Case of Chireya District, Zimbabwe. Climate, 12(8), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli12080126