Abstract

The interest in sustainability and energy efficiency is constantly increasing, and the noticeable effects of climate change and rising energy prices are fueling this development. The residential sector is one of the most energy-intensive sectors and plays an important role in shaping future energy consumption. In this context, modeling has been extensively employed to identify relative key drivers, and to evaluate the impact of different strategies to reduce energy consumption and emissions. This article presents a detailed literature review relative to modeling approaches and techniques in residential energy use, including case studies to assess and predict the energy consumption patterns of the sector. The purpose of this article is not only to review the research to date in this field, but to also identify the possible challenges and opportunities. Mobility, electrical devices, cooling and heating systems, and energy storage and energy production technologies will be the subject of the presented research. Furthermore, the energy upgrades of buildings, their energy classification, as well as the energy labels of the electric appliances will be discussed. Previous research provided valuable insights into the application of modeling techniques to address the complexities of residential energy consumption. This paper offers a thorough resource for researchers, stakeholders, and other parties interested in promoting sustainable energy practices. The information gathered can contribute to the development of effective strategies for reducing energy use, facilitating energy-efficient renovations, and helping to promote a greener and more sustainable future in the residential domain.

1. Introduction

Residential energy consumption plays a crucial role in the overall energy landscape, and it accounts for a significant portion of global energy demand [1]. This sector encompasses various energy-intensive activities, including space heating, water heating, lighting, and the operation of electric appliances and devices in millions of households worldwide [2]. The global population continues to grow [3], which leads to an increase in the number of residential units, and subsequently to higher energy requirements in meeting basic living needs. Additionally, rapid urbanization [4] and improved living standards in many regions have resulted in increased energy consumption per household. The sector’s energy demand is further influenced by factors such as population density, climate conditions, building characteristics, and socio-economic factors [5]. It is therefore crucial to understand and address the complexities of energy consumption to transition to a low-carbon future.

Energy fuels economic growth by powering industries, transportation, and essential services. As societies continuously evolve and technology becomes more pervasive, energy needs continue to increase. Nevertheless, the world is grappling with the adverse consequences of excessive energy use [6], such as greenhouse gas emissions, climate change, and resource depletion. It is therefore imperative to recognize that energy use is inextricably linked to global challenges [7], which makes it vital to explore diverse sustainable practices to find those that balance economic growth with environmental responsibility.

Improving energy efficiency and promoting sustainable energy practices have emerged as critical global priorities to reduce energy consumption in the residential sector [8]. The understanding of residential energy consumption patterns is a crucial step to design effective policies [9], implement targeted interventions, develop sustainable energy systems [10], and reduce our environmental footprint. Mitigating energy consumption in the residential sector requires a multi-faceted approach. Key strategies include the promotion of energy-efficient technologies, behavioral changes, and policy interventions. Adopting energy-efficient appliances, optimizing heating and cooling systems, implementing better insulation, and utilizing renewable energy sources are all effective measures through which to reduce energy consumption.

During our research, we studied many tools and technologies that facilitate the reduction in energy consumption in households. For example, smart meters can, depending on the technology and legal situation, enable real-time energy monitoring [11], which empowers homeowners to track and improve their consumption. Home energy management systems [12] allow for the automatic control and adjustment of energy demand and price signals based on electrical equipment. In addition, the development of energy storage and distributed energy resources offer opportunities to efficiently integrate renewable energy sources in residential systems [13].

Modeling plays an important role in shaping our understanding of energy use patterns and potential pathways toward sustainability [14]. It also provides a systematic framework through which to analyze the complex interplay of the various factors influencing residential energy use. The developed mathematical and computational models [15] that simulate energy use offer a systematic and structured approach in studying this field.

While previous studies have explored residential energy consumption and employed various modeling techniques, there remains a need for comprehensive and context specific approaches that consider the diverse factors that influence the energy use in different building types. This paper aims to address this gap by presenting a thorough examination of modeling approaches for residential energy consumption, which are divided into two main parts: (i) approaches for causal models, and (ii) models and approaches of relevance to the residential sector.

In this study, we review the existing literature on residential energy modeling and identify key studies that have contributed to the understanding of energy consumption in this sector. We highlight the advancements in modeling techniques and the insights gained from previous research.

Specifically, Section 2 will analyze the research approaches for causal models, as well as the research on models and approaches of relevance to the residential sector; meanwhile, Section 3 will provide a summary with the highlights of the research, and Section 4 will include a discussion of the findings.

2. Review of Modeling Techniques in Residential Energy Consumption

2.1. Causal Modeling

Causal models based on causal interference and analysis are powerful analytical tools that have been mainly used to identify and understand the cause and the effect relationships between the system variables. Unlike correlation, which only shows the association between the variables, causal models aim to determine the underlying mechanisms that lead to certain outcomes. In the context of modeling energy consumption in the residential sector, causal models can discover the complex interactions between various factors that influence household energy usage. Causal models, including structural equation modeling (SEM) [16], Bayesian networks [17], time series causal models [18], quasi-experimental designs [19], and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [20], have emerged as powerful tools through which to understand the complex relationships and interdependencies influencing energy consumption in households.

Causal modeling in residential energy consumption has expanded beyond traditional techniques, with structural causal models (SCMs) [21] gaining traction. SCMs allow researchers to capture both the direct and indirect causal relationships among variables, providing a more comprehensive understanding of energy usage drivers. Additionally, the potential outcome framework (POF) [22], commonly used in causal inference, is employed to estimate causal effects by comparing the observed and the counterfactual scenarios. SCMs and the POF serve as solid foundations as they enable the consistent representation of prior causal knowledge, assumptions, and estimates. The POF takes potential outcomes as a starting point and relates them to observed outcomes, while SCMs define a model based on observed outcomes from which potential outcomes can be derived. Causal models need to fulfill seven essential tasks [23] to be valuable tools for causal inference (Appendix A).

To simulate the effects on the behavior of energy consumption in the residential sector through causal models, researchers must carefully select and collect relevant data about household energy consumption, demographic information, weather data, and details on energy-efficient technologies. Furthermore, survey data can also provide valuable insights into behavioral factors influencing energy usage. Advanced statistical software and programming languages (e.g., R and Python) are indispensable tools for data analysis and for developing causal models. When selecting libraries to build causal models, several implementation aspects should be considered, such as the license type, programming language, documentation quality, and availability of support channels. Libraries that offer support tools for creating, modifying, and converting causal diagrams enhance the usability of causal models and their interpretability. Several libraries (Appendix B) implementing previous aspects have been studied, including DAGitty [24], DoWhy [25], Causal Graphical Models [26], Causality [27], and Causal Inference [28].

Research exploring the application of SCMs and the potential outcome framework to residential energy consumption is growing. For instance, the study of [29] utilized SCMs to analyze the causal relationships between the characteristics of the buildings, occupancy patterns, and energy use in residential buildings. Their findings emphasized the substantial impact of occupant behavior on energy consumption, uncovering valuable insights for energy efficiency initiatives. Another study [30] employed the directed acyclic graph (DAG) when randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were not feasible to assess the causal effects of household energy savings. Their research demonstrated that DAGs lead to a better understanding of the processes underlying intervention programs.

2.2. Modeling of Energy Systems in Buildings

Different models that provide a comprehensive understanding of energy use across different scales are examined. The examination covers a wide range of systems, from individual buildings to complex, large-scale energy supply systems. Generally small-scale system models tend to be far more detailed than large-scale system models, but that strongly depends on their intended use.

From a modeling perspective, energy system models consist of multiple interconnected models that work within a unified framework. The level of detail in these models is different as it depends on the scale of the representation, from complex representations of valves and pipes in a building to simplified representations of building blocks. The accuracy and the quality of the obtained results are greatly influenced by modeling methodology and the available computation time.

Table 1 provides a brief overview of some of the identified models, but the list is not exhaustive. The intention is to offer readers a glimpse into the possibilities and scales of energy system models. Ten different models have been examined, each with unique characteristics and applications.

Table 1.

Comparison of models for Energy Systems at Different Scales.

The above modeling tools do not only contribute to the comprehensive understanding of energy consumption patterns, but can also analyze the impact of various interventions in residential buildings. The utilization of these models can offer valuable insights into the patterns and origins of energy consumption, the optimization of energy usage, and can help to inform the decision-making process related to energy planning and management.

2.3. Modeling the Linkage of Mobility with Residential Energy

The seamless interaction between mobility and residential energy consumption plays a pivotal role in shaping sustainable urban living. As individuals commute to work, access essential services, and partake in recreational activities, their transportation choices directly impact their household’s energy usage. Electric vehicles (EVs) and the integration of smart mobility solutions introduce new dynamics to the energy landscape. With charging points being set up in homes, EVs now directly link the energy consumption for mobility with the household energy consumption.

The ever-increasing importance of sustainable urban living and energy-efficient mobility has paved the way for innovative traffic simulation models that align with the residential sector’s needs. Within this context, four influential simulation models, which are examined in this review—namely SUMO, MATSim, VISSIM, and PRIMES-TREMOVE—have emerged as powerful tools through which to analyze transportation dynamics (Table 2). With a focus on energy-conscious mobility and enhanced accessibility, these models offer valuable insights to the interplay between residential mobility patterns and energy consumption.

Table 2.

Noteworthy projects and models in traffic simulation and transportation modeling.

These methodologies have many proven success stories, but they have a fundamental limitation in capturing social behavior, which influences the decision of using specific transport modes. Thus, social behavior affects (i.e., time cost, comfort, monetary cost, or environmentally friendly awareness) are not included in the models. Actual platforms for road simulation do not cover these needs, either due to the impossibility to parameterize the initial system configuration according to social variables, or due to the distribution of such modules as additional commercial packages.

2.4. Modeling Approaches for Enhancing Energy Efficiency in Buildings

Improving energy efficiency in buildings is a pivotal issue for sustainable development. Modeling energy efficiency involves the use of various software tools and methodologies to simulate and analyze the energy performance of buildings. Some of the key measures that current tools consider are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Key measures considered in energy efficiency modeling tools.

Energy efficiency modeling tools in buildings encompass diverse categories, each tailored to address specific aspects of energy consumption. Whole-building simulation tools, like EnergyPlus [45] and DesignBuilder [46], offer dynamic simulations of overall building energy performance, thus allowing for the comprehensive analysis of heating, cooling, ventilation, lighting, and other systems. Energy labeling models [47] incorporate energy labels and certificates to assess and rate the buildings based on their energy performance and compliance with specific standards. Retrofit assessment models [48] focus on assessing the impact of renovation measures on building energy efficiency, thus aiding in identifying cost-effective retrofit strategies.

While modeling tools have advanced significantly, they do have limitations such as data accuracy and integration complexity. Accurate input data [49], such as occupancy patterns [50] and weather conditions, are crucial for reliable results, but obtaining them is challenging. Moreover, the interactions between building systems might not be fully captured and lead to potential inaccuracies [51]. Nevertheless, these modeling tools have demonstrated successes in performance prediction, cost-effectiveness, and policy support. They enabled informed decision making during the design phase leading to cost savings by identifying energy-efficient measures. Furthermore, many models support policy makers in developing energy efficiency regulations and standards.

Appendix D provides an overview of the energy efficiency measures in buildings, thereby focusing on renovation measures. These measures play a crucial role in improving energy efficiency and reducing energy consumption. Understanding and incorporating these approaches into simulation models is essential for the accurate representation of energy systems. The energy performance of buildings is a crucial factor in reducing emissions.

Energy efficiency measures in residential buildings need to be considered both for renovation measures and energy labels for appliances. Energy performance certificates play a special role, with the u-value being the main factor determining thermal losses [52]. Appendix F describes the effects of different energy-efficient measures on buildings (depending on the starting condition of the building and climate conditions), and refers to two different approaches for assessing the effects of efficiency measures: rough estimation, which provides a quick and approximate assessment; and exact calculation, which involves a more detailed and precise analysis using specialized software and a consideration of multiple parameters and factors.

2.4.1. Modeling Appliances

Modeling electric appliances is crucial for various demand-side energy management applications, as well as for providing simulation results with a high temporal resolution. Accurate and representative models of these appliances are essential for optimizing energy consumption, predicting energy loads, and developing effective strategies for demand response and energy conservation. This literature review explores how electric appliances are modeled, thereby presenting the tools commonly used for appliance modeling.

Analytical models [53] form the bedrock of appliance modeling, whereby mathematical equations based on physical principles to describe appliance behavior are employed. By simplifying the models without compromising essential characteristics, analytical approaches are effective for appliances with well-defined operating patterns, such as refrigerators, air conditioners, and electric heaters. On the other hand, empirical models utilize real-world data gathered from field measurements and surveys [54]. In leveraging machine learning techniques [55], like regression analysis and neural networks, empirical models offer greater flexibility in capturing the diverse operating conditions and behaviors of appliances (such as washing machines, dryers, and dishwashers). Hybrid models [56] represent a promising middle ground, including elements of analytical and empirical approaches to achieve a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. By integrating physics-based principles with data-driven techniques, these models excel at representing appliances with complex operational characteristics, including smart devices and variable-speed appliances.

The literature abounds with studies focused on developing load profiles for residential buildings, which consider aggregated energy consumption from different appliances to predict overall grid load. These models incorporate various factors, such as occupant behavior, the climate, and appliance penetration rates, to enhance their predictive capabilities. Individual appliance models have also been studied. For instance, the modeling of air conditioners [57] has garnered attention due to their substantial impact on peak electricity demand. Additionally, household lighting systems [58], refrigerators, water heaters, and other appliances have been examined to understand their energy consumption patterns. In emphasizing occupant behavior and user interactions with appliances, behavior-based models have emerged to provide more accurate predictions by considering factors such as usage schedules, appliance settings, and consumer preferences.

EnergyPlus stands out as a widely used building energy simulation program that integrates detailed physics-based models for various residential appliances. Through EnergyPlus, researchers can assess the energy performance of buildings and their systems [59], which encompass HVAC, lighting, and appliances. For appliances with complex control logic and non-linear behavior, MATLAB and Simulink [60] are used for developing analytical and empirical models. These platforms offer robust simulation capabilities and provide access to various machine learning algorithms in order to tackle intricate appliance behavior. OpenDSS (distribution system simulator) [61] is instrumental for power distribution system analysis. Researchers frequently incorporate appliance models into OpenDSS to study their impact on the overall grid and to explore demand-side management.

Occupant-Driven Energy Conservation

Modeling energy sufficiency is a complex issue that involves an extensive understanding and quantifying of the energy needed to meet occupant comfort while maintaining sustainable consumption levels. Energy sufficiency entails self-regulation and self-restriction, ensuring access to and consumption of energy without exceeding environmental limits. Unlike energy efficiency, which often relies on modern and expensive equipment, energy sufficiency emphasizes low or no-cost interventions, such as behavioral changes and appropriate adjustments to existing household equipment.

For instance, the study of [62] aimed to assess and model energy sufficiency in the residential sector by analyzing occupant behavior and its impact on energy consumption. In utilizing a behavior-based simulation model, the aforementioned study estimated the energy demand for heating, cooling, lighting, and appliances by considering occupant preferences and schedules. Various energy-saving interventions were included, such as thermostat settings and the adoption of energy-efficient appliances. By comparing the simulated energy consumption with actual usage, the study examined the potential of behavior change interventions to achieve energy sufficiency while maintaining occupant comfort. The findings offer valuable insights into the role of occupants in shaping energy consumption patterns and provide evidence-based strategies for promoting energy sufficiency.

2.4.2. Modeling HVAC Systems

HVAC systems have a substantial potential to (i) provide flexibility to the energy system, and (ii) improve the energy efficiency of a building. In terms of mathematical modeling and simulation, three parts need to be considered: (i) HVAC components, (ii) HVAC control, and (iii) HVAC systems in general. HVAC control is the control mechanism that decides when the devices work, as well as the working parameters. The HVAC system describes how the different components are linked together within the building.

Table 4 provides an overview of the different models that are available for simulating heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC). The listed models encompass a wide range of technologies, from tankless water heaters to air conditioning, as well as ventilation systems. Each model represents a unique approach to simulating different HVAC components.

Table 4.

Overview of HVAC System Models.

2.5. Modeling Energy Management Systems (EMS)

Energy management systems (EMS) utilize measured data, forecasts, and self-learning algorithms to optimize energy consumption by shifting flexible loads to times when it is more economic, ecological, or convenient. There exists a multitude of different EMS options tailored with different consumer ranges, which can be classified into clusters, namely (1) open-source EMS, (2) research EMS, and (3) commercial EMS (Table 5).

Table 5.

A brief overview of the different types of EMS.

Modeling energy management systems involves considering their specific functionalities, integration capabilities, and potential applications in achieving energy sufficiency within the residential sector. The above table demonstrates the diverse range of EMS options available and the benefits they offer in terms of optimizing energy consumption, promoting energy efficiency, and fostering user engagement in energy conservation.

2.6. Modeling Energy Storage

Energy storage provides energy systems with the necessary flexibility to mitigate the effects of an increasing amount of variable renewable energy. Effective energy storage models can help optimize energy usage, improve system resilience, and contribute to a more sustainable and efficient energy system design.

This study focuses on the mathematical representation of the storage system itself and the models describing its control strategy and interactions with other systems. The storage systems considered in this study are clustered according to the technology used. The relevant clusters are as follows:

- Electro-Chemical Storages

- ◦

- Classical Batteries

- ▪

- Li-Ion Technology

- ▪

- Nickel Cadmium Technology

- ▪

- Nickel Metal Hydride Technology

- ▪

- Zinc–Air Technology

- ▪

- Sodium Sulfur Technology

- ▪

- Sodium Nickel Chloride Technology

- ▪

- Lead Acid Technology

- ◦

- Flow Batteries

- ▪

- Vanadium Redox Flow Technology

- ▪

- Hybrid Flow Technology

- Chemical Storages

- ◦

- Hydrogen

- ◦

- Synthetic natural gas

- ◦

- Biomethanation

- Mechanical

- ◦

- Flywheel

- ◦

- Pressure

- Electrical

- ◦

- Supercapacitor

- ◦

- Superconducting Magnetic

- Thermal

- ◦

- Sensible Heat

- ◦

- Latent Heat

- ◦

- Thermo-Chemical

With the above categorization in place, Table 6 sets the technical representation of the storage system. The models presented here show basic simulation approaches that are valid for different technologies.

Table 6.

Technical representation of Energy Storage System Models.

2.7. Modeling Generation Technologies

The increasing prominence of decentralized generation capacities has elevated the significance of accurately simulating these technologies in the household sector. Our study focuses on modeling approaches tailored to generation technologies that are relevant to residential settings, including PV generation (rooftop PV, facade PV, and bifacial PV), small-scale wind turbines, CHP technologies (gas-powered CHP, hydrogen-powered, and CHP fuel cells), and combustion engines. Each technology exhibits distinct characteristics that require unique modeling techniques to ensure accurate representation and performance simulation. To provide a comprehensive overview, as was summarized in Table 7, the different modeling approaches specific for generation technologies were considered.

Table 7.

Different Modeling approaches for specific generation technologies.

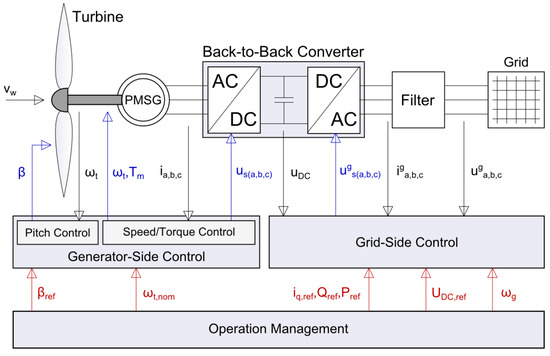

Figure 1.

Detailed Model of a wind turbine [126].

2.8. Modeling Business Models in the Field of Electrical Consumption on a Household Level

The European Union’s energy landscape is experiencing a transformative shift with energy consumers playing a more active role in the energy system. Decentralized generation capacities and controllable flexible loads have unlocked opportunities for consumers to interact with the energy market in innovative ways, triggering the emergence of new business models. Table 8 introduces the concept of business models in the household sector, setting the stage for the exploration of various models that offer consumers greater control over their energy consumption and costs.

Table 8.

Overview of business models available to household energy consumers.

2.9. Urban Energy Modeling and Microclimates

To achieve sustainability in a greater scale however, urban energy modeling techniques are being employed that consider the residential sector a pivotal factor in contributing to the urban energy canvas. The energy requirements of residential buildings such as heating, cooling, lighting, and everyday appliances reflect the city’s energy footprint. Conversely, the density, the infrastructure, and the design of the urban environment exert a tangible influence on residential energy use.

Currently, urban energy modeling is progressing with improved data availability and more sophisticated simulation techniques that encompass diverse factors such as transportation, infrastructure, and land use. Recent research in urban modeling spheres underscores the significance of data acquisition techniques in refining urban building energy models. The study of [133] aggregated and analyzed data from diverse sources to gain models with the appropriate granularity in order to capture the nuances of energy consumption in different urban zones. Upon this, another study [134] explored the pertinent questions that drive the evolution of urban energy modeling. Their inquiries ranged from the impact of urban form in energy demand to the integration of renewable energy sources within urban contexts.

Urban microclimates indeed correlate with both urban and residential modeling. Microclimates are influenced by factors such as building density, vegetation, and surface materials. It impacts energy demand, heat distribution, and cooling strategies in both contexts. The integration of microclimate data enhances the accuracy of energy models for both areas. The study of [135] investigated the relevant techniques in urban thermal and wind environments, concluding that current techniques cannot pave the way for accurate strategies; furthermore, it suggested that future modeling assessments should include urban typologies and data-driven approaches for more accurate decisions. Another study [136] focused on the recent advancements of urban microclimates on urban wind and thermal environments that were found (although field measurements were the most necessary for this type of assessment, the techniques used to achieve the desired accuracy in results were missing).

3. Summary

The modeling of residential energy consumption has gathered significant attention from researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders due to its potential to inform sustainable energy practices and policies. In this study, we examined various modeling approaches and techniques including simulation-based approaches, modeling, statistical methods, machine learning algorithms, and optimization models.

To better structure and classify the different approaches for causal models, a taxonomy of the tasks that causal models carry out is presented (Appendix A), as well as the different libraries (Appendix B) that were used to implement the causal models on these aspects. Following the classification and research conducted for causal models, we continued our research by analyzing and classifying the possibilities to address the energy-related aspects of residential buildings. The different aspects considered were very heterogeneous; thus, no common approach could be identified in how to address them.

The analysis of models for different scales of energy systems provided a deeper understanding of energy consumption (thermal or electric) in different settings. They often work as a framework where multiple different, more or less detailed models are included and soft-linked. A total of 10 different existing models were analyzed and discussed. The large-scale energy system models were neglected as the focus of this paper are residential buildings rather than entire countries (as the case in large-scale energy system models).

The option of shifting loads or using certain loads at certain times is a potential option for residential consumers. But there are certain loads (appliances) that are not available for load shifting due to technical, user behavioral or comfort restrictions. Modeling these loads generally comes down to considering pre-defined load profiles, which are applied once the device is activated. Another important option that affects the energy consumption of residential users are energy efficiency approaches, which include the following: (i) renovation measures of the building envelope, including the replacement or upgrade of windows and wall/roof thermal insulation, and (ii) purchasing and using more energy-efficient appliances with better energy labels (Appendix C).

The latter can be represented in models by using new load profiles for non-flexible appliances or improved parameters in technical models of appliances that can be used flexibly. Simulating renovation measures comes down to changing the technical parameters of buildings (e.g., the u-values of building shells). For this purpose, substantial research of different parameters has been conducted. Different technical parameters for types of insulation, wall material, window types, etc., have been identified and described in detail in this study (Appendix D).

In order to obtain more control over energy consumption and the behavior of devices, residential consumers can make use of energy management systems (EMSs). There are a multitude of different options of EMSs available on the market that differ in their price, applicability, and management options that are provided to the user. This study provides examples of EMSs for three different categories: (1) open-source, (2) research, and (3) commercial. The purpose of this research was to create an understanding of the options these EMSs provide.

Energy storage models are one of the key options to make residential consumption more flexible. In this direction, we identified a wide variety of technologies, from battery storage systems (and subtypes) over thermal storages to mechanical storages. Storage systems are modeled using mathematical equations, but there are many different approaches for the different technologies available; their differentiation is based on the degree of detail and time required to solve the underlying equations. We presented a total of 14 different approaches for 5 different storage types.

Apart from storage systems, there are certain types of devices that can be controlled by EMSs to change their operational behavior in order to meet certain goals. Amongst those, the heating ventilation air conditioning systems (HVAC systems) and electric vehicles (EV) are the most relevant for the residential sector, and these were analyzed extensively. On the one hand, for the HVAC systems, different technologies are relevant, for which a multitude of different modeling approaches exist. This study provides a summary of general approaches for these technologies, followed by a set of libraries with commonly used models for them. On the other hand, for the EVs, a review of different approaches for modeling the mobility needs are also presented and discussed.

One of the key changes to the energy system of past years was the technological advancements in the decentralized generation technologies. They provide residential consumers with the means to generate their own energy for self-consumption or other purposes. The following technologies were deemed relevant for the residential sector and are presented in this paper: (1) PV/solar generation, (2) micro-wind generation, and (3) combined heat and power generation (CHP). For the latter, the two different control strategies (electricity-led or heat-led) and the different fuels (gas-powered, biomass, or hydrogen) were considered. A total of nine different approaches used to model these three types of generation technologies were identified during the research.

The last relevant aspect considered during this research was the business models related to energy use in the residential sector. Formerly passive consumers (especially residential consumers) are slowly transitioning to becoming more active participants in the energy system, as suggested by the EU Climate Policy Package. As such, new businesses are emerging that aim at providing new services to residential consumers to generate profits for the businesses and benefits of residential consumers. The most relevant business models to be considered in this study were as follows: energy as a service, peer-to-peer electricity trading, aggregators, community ownership models, and pay-as-you-go models.

Overall, this study provides an overview of the different aspects to be considered in the modeling of residential energy consumption, as well as provides the reader with a general knowledge on different methodologies and approaches when trying to create a holistic representation of household energy consumption and the underlying decision processes.

4. Discussion

In conclusion, the research presented in this study shows a wealth of modeling approaches and techniques that are able to predict and simulate the energy consumption of the residential sector. Although the presented techniques offer valuable insights in understanding the complexities of energy usage, one question arises regarding the sufficiency of current techniques: are current techniques able to fully evaluate the residential sector’s energy consumption?

The answer to this question has various aspects regarding future development. Energy efficiency is very clearly one of the most important aspects in reducing energy consumption, but the literature shows that renovation measures are often overlooked. Modeling techniques should encompass all aspects of energy efficiency to deliver a holistic understanding regarding the energy savings of residential buildings. During this research, we identified the significant role of energy sufficiency, which has limited references. Behavioral and lifestyle changes have a vital role in achieving sustainability, and modeling efforts should aim to integrate these into the current models that measure energy sufficiency.

Although the existing models address the aspects of mobility and electric appliances, current research suggests that its scope should be broadened to capture more diverse trends and other evolving elements that can accurately represent the impact of EVs and advanced appliances.

This extensive literature review revealed that the existing models are not sufficient on their own. Furthermore, to achieve a sustainable residential energy future, the integration of all approaches should be considered. This means that there is a need to develop an interconnected modeling framework so effective strategies can be developed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.N., R.P., J.G., A.A. and P.F.; methodology, T.N., R.P., J.G., A.S. and P.F.; validation, T.N., R.P., J.G., A.S. and A.A.; formal analysis, T.N., R.P., J.G., A.S. and A.A.; data curation, T.N., R.P. and J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.N., R.P., J.G., A.S., A.A., P.F. and E.Z.; writing—review and editing, T.N., R.P., J.G., A.A., P.F. and E.Z.; visualization, T.N., R.P. and J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 891943.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program under grant agreement no. 891943. We would like to thank Cruz Enrique Borges for his helpful comments in a previous version of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Seven Essential Tasks That Causal Models Need to Fulfill [16] to Be Valuable Tools for Causal Inference

- Encoding Causal Assumptions—Transparency and Testability: Transparency enables analysts to discern whether the assumptions encoded are plausible or whether additional assumptions are warranted. Testability permits one to determine whether the assumptions encoded are compatible with the available data and, if not, identify those that need repair. Testability is facilitated through a graphical criterion, which provides the fundamental connection between causes and probabilities [16].

- Do-calculus and the control of confounding: For models where the “back-door” (the graphical criterion through which to manage confounding) criterion does not hold, a symbolic engine is available called do-calculus, which predicts the effect of policy interventions whenever feasible [137].

- The Algorithmization of Counterfactuals: This task formalizes counterfactual reasoning within graphical representations. Every structural equation model determines the truth value of every counterfactual sentence.

- Mediation Analysis and the Assessment of Direct and Indirect Effects: This task concerns the mechanisms that transmit changes from a cause to its effects, which is essential for generating explanations. Counterfactual analysis must be invoked to facilitate this identification.

- Adaptability, External Validity, and Sample Selection Bias: Robustness is recognized by AI researchers as a lack of adaptability that comes out when environmental conditions change. The do-calculus offers a complete methodology for overcoming bias due to environmental changes. It can be used both for readjusting learned policies to circumvent environmental changes, and for controlling disparities between non-representative samples and a target population [138].

- Recovering from Missing Data: Using causal models of the missingness process can formalize the conditions under which causal and probabilistic relationships can be recovered from in-complete data and, whenever the conditions are satisfied, produce a consistent estimate of the desired relationship.

- Causal Discovery: The d-separation criterion detects and enumerates the testable implications of a given causal model. This opens the possibility of inferring, with mild assumptions, the set of models that are compatible with the data, and to represent this set compactly; in certain circumstances, the set of compatible models can be pruned significantly to the point where causal queries can be estimated directly from that set [139].

Appendix B

Table A1.

Main characteristics of the different libraries that are used to build causal models.

Table A1.

Main characteristics of the different libraries that are used to build causal models.

| Packages | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspects | DAGitty | DoWhy | Causal Graphical Models | Causality | Causal Inference |

| Encoding Causal Assumptions—Transparency and Testability | X | X | X | X | X |

| Do-calculus and the control of confounding | X | X | X | X | X |

| The Algorithmization of Counterfactuals | X | X | X | X | |

| Mediation Analysis and the Assessment of Direct and Indirect Effects | X | X | X | X | X |

| Adaptability, External Validity, and Sample Selection Bias | X | X | |||

| Recovering from Missing Data | X | ||||

| Causal Discovery | X | X | X | X | |

| Support tools to write Causal Diagrams | X | X | X | X | X |

| License | GNU | MIT | MIT | Open | BSD |

| Programming Language | R | R/Python | Python | Python | Python |

| Documentation and support channels | X | X | X | X | |

Appendix C

Table A2.

Energy labels and Certificates.

Table A2.

Energy labels and Certificates.

| LEED (USA) | LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) is a widely recognized green building rating system that provides a framework for highly efficient and sustainable buildings. Available for virtually all building types, it provides a framework for healthy, highly efficient, and cost-saving green buildings. LEED certification is a globally recognized symbol of sustainability achievement and leadership. |

| BREEAM (UK) | BREEAM is an internationally recognized sustainability assessment method that certifies the sustainability performance of buildings, communities, and infrastructure projects. It recognizes and reflects the value in higher performing assets across the built environment lifecycle, from new construction, to currently used, to refurbishment. |

| Energy Star (US) | Energy Star promotes energy efficiency and provides information on energy consumption for various products and devices. The program provides information on the energy consumption of products and devices via different standardized methods. The Energy Star label is found on more than 75 different certified product categories, homes, commercial buildings, and industrial plants. |

| Rescaled EU Labels (EU) | The rescaling of EU energy labels (A–G scales) addresses the appearance of higher energy-efficient products. Class A is initially empty to leave room for technological developments in the future. Every appliance that requires an energy label needs to be registered in EPREL (European Product Registry for Energy Labeling) before being placed on the European market. A QR code is placed on the label for the client to have access to this public information. An important change in the new eco-design rules is the inclusion of elements to further enhance the reparability and recyclability of appliances, e.g., ensuring the availability of spare parts, access to repair, and the maintenance information for professional repairers. |

| Energy Performance Certificates (EU) | Energy performance certificates (EPCs) assess the energy performance of buildings and provide recommendations for energy efficiency improvements. Following the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), an EPC shall include the energy performance of a building and its reference values, as well as the recommendations for the cost-optimal or cost-effective improvements of the energy performance of a building or building unit. Within the national context, it is up to the Member States to decide on the performance rating of the representation (i.e., energy level vs. continuous scale), as well as the type of recommendations (i.e., standardized vs. tailor-made). |

Appendix D

Table A3.

Energy Efficiency Approaches in Buildings (renovation measures).

Table A3.

Energy Efficiency Approaches in Buildings (renovation measures).

| Windows | Installation of Low-Emissivity Glass | Low-e storm windows with multilayer nanoscale coatings are utilized to reduce radiative heat loss and solar heat gain [101]. The primary purpose of a low-e storm window is to reduce the u-values of buildings. These low-e coatings are called solar selective or solar control low-e coatings. |

| Installing Window Shading | Window shades regulate lighting and reduce solar gains, thus contributing to energy efficiency. | |

| Replacement with Multi-Glazed Windows | Upgrading to multiple glazes with insulation gases and efficient framing materials improves energy efficiency. | |

| Insulation | External Thermal Insulation | Adding insulation to the exterior walls of a building with various techniques and materials enhances energy efficiency. A better insulation can be reached through multiple different approaches; for instance, by installing thermal insulation compound systems (a combination of different thermal insulation types), installing a curtain wall (often a wooden wall in front to the core wall of the building with insulation in between), or through implementing a core insulation (insulation is directly injected into the wall of a building). |

| Internal Thermal Insulation | Achieved by applying insulation to the interior walls, floors, or roof of a building to reduce heat transfer. Depending on the area to which the insulation is applied, different methods and materials can be used. Regarding attics, for instance, it makes a difference whether or not it should be accessible, in which case insulation panels (on which you can walk), the installation of a raised floor, or using pour-in insulation is an option. It is important to differentiate between cavity walls, where pour-in insulation or insulation mats can be used, or—if there are solid walls—where insulation panels or insulation mats need to be used. | |

| Floor Insulation | This method involves insulating floors above cellars or on the ground floor, particularly when floor heating is present. The type of insulation and insulation material strongly depends on the specifics of the building and the floor, as well as whether there is floor heating installed or not. Regardless of these specifics, the insulation material must be durable due to the constant strain it has to endure. | |

| Roof Sealing | Thermal losses and gains of the roof area represent a very large proportion of the total losses. As such the thermal insulation of the roof plays an important role when trying to improve the efficiency of a building. Insulation options are below rafters, in between rafters, on rafters, insulation for pitched roofs, as well as internal or external insulation for flat roofs. Currently, there are multiple different materials with different properties available. | |

| Roof Sarking | Roof sarking is the process of installing a thin insulating membrane directly underneath the roof. It works as a sort of “reflective” insulation with the purpose of reflecting radiant heat and thus preventing it from entering the building from outside (summertime) or leaving the building from the inside (wintertime). | |

| Air–sealing | Sealing houses against air leakage is one of the simplest upgrades to increase comfort in a house. Air leakage accounts for 15–25% of winter heat loss in buildings, and it can contribute to a significant loss of coolness in climates where air conditioners are used. The first step is to detect leaks by inspecting the doors, windows, edges, and spots where different materials meet each other, as well as checking vents, skylights, and exhaust fans. A more professional approach is to use a blower door, which reduces the pressure in the house. In this, air from outside will enter the house because of the pressure difference. The air leakage rate can be measured this way and, through using smoke, the actual leaks can be detected. | |

| Insulation of Pipes | Heat losses in the pipes of the heating system account for a large (up to 50% [140,141]) of the total heat losses in central European buildings. This is due to the fact that the pipes have to be kept at operating temperature and are constantly losing thermal energy. Insulation of pipes consists of installing shells or ducts made from a thermal insulator such as glass or rock wool (from basalt) in the pipes. In addition to mineral wool, other materials such as plastic foam or vapor barrier coatings can also be used. |

Appendix E

Table A4.

TRNSYS libraries and tools to simulate different HVAC components.

Table A4.

TRNSYS libraries and tools to simulate different HVAC components.

| Libraries | Description |

|---|---|

| TYPE 753 | Type 753 models involve a heating coil that is used in one of three control modes. The heating coil is modeled using a bypass approach in which the user specifies a fraction of the air stream that bypasses the coil. The remainder of the air stream is assumed to exit the coil at the average temperature of the fluid in the coil. The air stream passing through the coil is then remixed with the air stream that bypassed the coil. In its unrestrained (uncontrolled) mode of operation, the coil heats the air stream as much as possible given the inlet conditions of both the air and the fluid streams. |

| TYPE 917 | Air-to-water heat pump—This component models a single-stage air source heat pump. |

| TYPE 919 | Normalized water source heat pump—This component models a single-stage liquid source heat pump with an optional desuperheater for hot water heating. |

| TYPE 922 | Two-speed air-source heat pump (normalized)—Type 922 models use a manufacturer’s catalog data approach to model an air-source heat pump (air flows on both the condenser and evaporator sides of the device). |

| TYPE 927 | Normalized water-to-water heat pump—This component models a single-stage water-to-water heat pump. |

| TYPE 941 | Air-to-water heat pump—This component models a single-stage air-to-water heat pump. |

| TYPE 954 | Air-source heat pump/split system heat pump—Type 954 models use a manufacturer’s catalog data approach to model an air-source heat pump (air flows on both the condenser and evaporator sides of the device). |

| TYPE 966 | Air-source heat pump—DOE-2 approach —Uses the approach popularized by the DOE-2 simulation program in which the performance of an electric air-source heat pump can be characterized by bi-quadratic curve fits. |

| TYPE 1221 | Normalized two-stage water-to-water heat pump—This component models a two-stage water-to-water heat pump. |

| TYPE 1247 | Water-to-air heat pump section for an air handler—This component models a single-stage liquid-source heat pump. |

| TYPE 1248 | Air-to-air heat pump section for an air handler—Type 1248 models use a manufacturer’s catalog data approach to model an air-source heat pump (air flows on both the condenser and evaporator sides of the device). |

| TYPE 930 | Electric heating coil. |

| TYPE 664 | Electric unit heater with variable speed fan, proportional control, and damper control—Type 664 models involve an electric unit heater whose fan speed, heating power, and fraction of outdoor air are proportionally and externally controlled. |

| TYPE 929 | Gas heating coil—Type 929 models represent an air heating device that can be controlled either externally or set to automatically try and attain a set point temperature, much like the Type 6 models do for fluids. |

| TYPE 967 | Gas-fired furnace—DOE-2 approach—In this model, the performance of a forced-air furnace is characterized by a constant heat input ratio. |

| TYPE 651 | Residential cooling coil (air conditioner)—Type 651 models involve a residential cooling coil, which is more commonly known as a residential air conditioner. |

| TYPE 508 | Cooling coil with various control modes—Type 508 models involve a cooling coil that uses one of four control modes. |

| TYPE 752 | Simple cooling coil—Type 752 models include a cooling coil that use a bypass fraction approach. |

| TYPE 921 | Air conditioner (normalized)—The component models of this type use an air conditioner for residential or commercial applications. |

| TYPE 923 | Two-speed air conditioner (normalized)—The component models of this variety involve a two-speed air conditioner for residential or commercial applications. |

Appendix F

Table A5.

Energy efficiency Impact of Window and Insulation Measures.

Table A5.

Energy efficiency Impact of Window and Insulation Measures.

| Rough Estimation | Exact Calculation | |

|---|---|---|

| Replacing Windows | The effect of replacing windows strongly depends on the starting position. If windows have high u-values, it is highly efficient to change them. The effect depends on the climate and weather conditions. To estimate the effects of changing windows the following rough calculation is quite useful: where is the heat loss of the building in kWh, is the u-value in W/(m2 K), is the total area of the windows in m2, is the temperature difference between inside and outside in K, and is the considered time in hours. Taking this formula, the heat losses and heat gains can be roughly estimated before and after the window change. | In addition to the u-value, many other parameters affect the heat loss and gain through windows. For example, the alignment of the windows and their relative position to the sun, the amount of radiation penetrating through the windows, or the air leakage. Using real climate data (temperature and solar radiation) will improve the estimation accuracy. Detailed, dynamic simulations are supported by building simulation software like TranSys, EnergyPlus, or IdaICE. Simulations with the old windows should be implemented with new ones. |

| Storm Windows | Storm windows are the most effective when they are attached to older, inefficient, single-pane primary windows that are still in decent, operable condition. Adding an interior storm window to a new, dual-pane primary window will not improve performance much, and adding one to a decaying, old primary window will not extend the primary window’s lifespan even though it will give the efficiency rating a boost. As an example, the change in the parameters due to the addition of different types of storm windows to a wood double-hung, single-glazed window is shown below. The study of [142] provided the values shown in Table A6 for the different types of windows and frames. | |

| Improving Insulation | Similar to the effects of changing windows, the effect of adding insulation to a house strongly depends on the starting situation. Adding insulation to a house with old solid bricks in a cold climate will affect the energy efficiency enormously. Insulation protects from heat losses on cold days and from heat gains on hot days. In order to estimate the effects of insulation, the following formula is used: The u-value is the parameter accounting for the heat loss of a building in W/(m2 K). describes the thermal conductivity of the insulation in W/(m·K), and stands for the thickness of the insulation in m. The u-value can then be used to make an estimation of the heat loss through the walls, the roof, and the floor via the formula given for . | In addition to the u-value, other parameters affect the heat loss and gain through walls/roof and floors. For example, the air leakage and the heat transfer resistance at the surfaces. In addition, using real climate data (temperature and solar radiation) will improve the exactness of the estimation. Detailed, dynamic simulations are supported by building simulation software like TrnSys (http://www.trnsys.com/), EnergyPlus (https://energyplus.net/), or IdaICE (https://www.equa.se/en/ida-ice). When estimating the effect of insulating houses, two simulations need to be performed: one with and one without insulation. |

| Adding shading | Adding exterior shades has no effect on the u-value of the building but affects its solar gains [133]. The effects of shading can, according to [134], be calculated with the solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC): where is the heat gain coefficient for external shading, the value for internal shading, and the value for glazing. The solar heat gain coefficient describes the factor of solar radiation/heat that passes into the buildings. The coefficient can reach values between 0 and 1. The solar heat gain is strongly affected by one’s location and the angle at which the sun shines on a building. According to [143], depending on the type of shading and the angle of the shades, the values of 0.39 for horizontal shades, 0.7 for vertical shades, and 0.33 for combined shades can be reached. For internal shades, depending on the type of window glazing and the type of internal shade, values between 0.25 (white reflective, translucent screens in combination with 6 mm single glazing) and 0.94 (dark weave draperies in combination with low-e double-glazing windows) can be reached. | |

Table A6.

Example of the Representative values for different Storm Window Types [101].

Table A6.

Example of the Representative values for different Storm Window Types [101].

| Base Window | Storm Type | u-Value (W/m2K) | SHGC | VT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood Double-Hung, single-glazed | None | 5 | 0.61 | 0.66 |

| Clear exterior | 2.7 | 0.54 | 0.57 | |

| Clear interior | 2.6 | 0.54 | 0.59 | |

| Low-e, exterior | 2 | 0.46 | 0.52 | |

| Low-e, interior | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.54 |

References

- del Pablo-Romero, M.P.; Pozo-Barajas, R.; Yñiguez, R. Global changes in residential energy consumption. Energy Policy 2017, 101, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassileva, I.; Campillo, J. Increasing energy efficiency in low-income households through targeting awareness and behavioral change. Renew. Energy 2014, 67, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdren, J.P. Population and the energy problem. Popul. Environ. 1991, 12, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q. The trends, promises and challenges of urbanisation in the world. Habitat Int. 2016, 54, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Cheng, L.; Li, J.; Hahn, P.R.; Liu, H. A Survey of Learning Causality with Data. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y. Urban Form and Residential Energy Use. J. Plan. Lit. 2013, 28, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 2012, 488, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yelisieieva, O.; Lyzhnyk, Y.; Stolietova, I.; Kutova, N. Study of Best Practices of Green Energy Development in the EU Countries Based on Correlation and Bagatofactor Autoregressive Forecasting. Econ. Innov. Econ. Res. J. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambalid, A. Energy Efficiency in Residential Buildings. Delhi Technological University, 2023. Available online: http://dspace.dtu.ac.in:8080/jspui/handle/repository/20094 (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Kitsopoulou, A.; Zacharis, A.; Ziozas, N.; Bellos, E.; Iliadis, P.; Lampropoulos, I.; Chatzigeorgiou, E.; Angelakoglou, K.; Nikolopoulos, N. Dynamic Energy Analysis of Different Heat Pump Heating Systems Exploiting Renewable Energy Sources. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastry, L.; Karri, S.P.K. Smart Home Energy Management Using Non-intrusive Load Monitoring. In Sustainable Energy Solutions with Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain Technology, and Internet of Things; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; p. 30. ISBN 9781003356639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateen, A.; Wasim, M.; Ahad, A.; Ashfaq, T.; Iqbal, M.; Ali, A. Smart energy management system for minimizing electricity cost and peak to average ratio in residential areas with hybrid genetic flower pollination algorithm. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 77, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkadeem, M.R.; Abido, M.A. Optimal planning and operation of grid-connected PV/CHP/battery energy system considering demand response and electric vehicles for a multi-residential complex building. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsani, G.B.; Casquero-Modrego, N.; Trueba, J.B.E.; Bandera, C.F. Empirical evaluation of EnergyPlus infiltration model for a case study in a high-rise residential building. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, D.; Raftery, P.; Keane, M. A review of methods to match building energy simulation models to measured data. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 37, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Zhao, Z.-Y.; Li, H.; Rehman, A. The influence of consumers’ intention factors on willingness to pay for renewable energy: A structural equation modeling approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 21747–21761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanpour, K.; Nehrir, M.H.; Sheppard, J.W.; Kelly, N.C. Agent-Based Modeling in Electrical Energy Markets Using Dynamic Bayesian Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 4744–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferkingstad, E.; Løland, A.; Wilhelmsen, M. Causal modeling and inference for electricity markets. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Wu, F.; Ye, D.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, L. Exploring the effects of energy quota trading policy on carbon emission efficiency: Quasi-experimental evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2023, 124, 106791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiks, E.R.; Stenner, K.; Hobman, E.V.; Fischle, M. Evaluating energy behavior change programs using randomized controlled trials: Best practice guidelines for policymakers. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, G.; Karagol, E. Structural break, unit root, and the causality between energy consumption and GDP in Turkey. Energy Econ. 2004, 26, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong-gui, M.; Xiao-han, X.; Xue-er, L. Three analytical frameworks of causal inference and their applications. Chin. J. Eng. 2022, 44, 1231–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, J. The seven tools of causal inference, with reflections on machine learning. Commun. ACM 2019, 62, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, J.; van der Zander, B.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Liśkiewicz, M.; Ellison, G.T. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: The R package ‘dagitty’. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinmohammadi, F.; Han, Y.; Shafiee, M. Predicting Energy Consumption in Residential Buildings Using Advanced Machine Learning Algorithms. Energies 2023, 16, 3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, N.; Steg, L.; Albers, C. Studying the effects of intervention programmes on household energy saving behaviours using graphical causal models. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 45, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soytas, U.; Sari, R. Energy consumption and GDP: Causality relationship in G-7 countries and emerging markets. Energy Econ. 2003, 25, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Abualdenien, J.; Singh, M.M.; Borrmann, A.; Geyer, P. Introducing causal inference in the energy-efficient building design process. Energy Build. 2022, 277, 112583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, R.; Yimin, Z.; Supratik, M. Application of Causal Inference to the Analysis of Occupant Thermal State and Energy Behavioral Intentions in Immersive Virtual Environments. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 730474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Ai, B.; Li, C.; Pan, X.; Yan, Y. Dynamic relationship among environmental regulation, technological innovation and energy efficiency based on large scale provincial panel data in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugradt, N.D. Modellierung von Wasser und Energieverbräuchen in Haushalten. Ph.D. Dissertation, Technische Universität Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy. EnergyPlusTM Version 9.4.0 Documentation Guide for Interface Developers; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Lund, H.; Zinck Thellusfen, J. EnergyPLAN—Advanced Energy Systems Analysis Computer Model. 2020. Available online: https://zenodo.org/record/4001541 (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Riederer, P. Ninth International IBPSA Conference Montréal, Canada 15–18 August 2005, Matlab/Simulink for Building and Hvac Simulation—State of the Art, Centre Scientifique et Technique du Bâtiment, 84, Avenue Jean Jaurès, 77421 Marne la Vallée Cedex 2, France. Available online: http://www.ibpsa.org/proceedings/BS2005/BS05_1019_1026.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Simscape™ Electrical™ User’s Guide (Specialized Power Systems)© COPYRIGHT 1998–2019 by Hydro-Québec and The MathWorks, Inc. The MathWorks, Inc.: Apple Hill DriveNatick, MA, USA. Available online: https://toaz.info/doc-view-2 (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Beckman, W.A.; Broman, L.; Fiksel, A.; Klein, S.A.; Lindberg, E.; Schuler, M.; Thornton, J. TRNSYS The most complete solar energy system modeling and simulation software. Renew. Energy 1994, 5, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathissa, P. Design and Assessment of Adaptive Photovoltaic Envelopes. Chapter 3.2.3 RC Model for Building Energy Demand. Ph.D. Thesis, 2017; pp. 33–35. Available online: https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/handle/20.500.11850/212017 (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Beausoleil-Morrison, I.; Kummert, M.; Macdonald, F.; Jost, R.; McDowell, T.; Ferguson, A. Demonstration of the new ESP-r and TRNSYS co-simulator for modelling solar buildings. Energy Procedia 2012, 30, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjrsell, N.; Bring, A.; Eriksson, L.; Grozman, P.; Lindgren, M.; Sahlin, P.; Shapovalov, E.; Ab, B. IDA Indoor Climate and Energy. In Proceedings of the Building Simulation; Volume 2, pp. 1035–1042. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=1505526ddf0183237ed34e83ec1c7011efe0b5bf (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Wetter, M.; Zuo, W.; Nouidui, T.S.; Pang, X. Modelica Buildings library. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2014, 7, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajzewicz, D.; Erdmann, J.; Behrisch, M.; Bieker, L. Recent Development and Applications of SUMO-Simulation of Urban MObility. Int. J. Adv. Syst. Meas. 2012, 5, 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Horni, A.; Nagel, K.; Axhausen, K.W. The Multi-Agent Transport Simulation MATSim; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellendorf, M. VISSIM: A Microscopic Simulation Tool to Evaluate Actuated Signal Control including Bus Priority. In Proceedings of the 64th ITE Annual Meeting, Dallas, TX, USA, 16–19 October 1994; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Siskos, P.; Capros, P. Primes-Tremove: A Transport Sector Model for Long-Term Energy-Economy-Environment Planning for EU. In Proceedings of the 20th Conference of the International Federation of Operational Research Societies, Barcelona, Spain, 13–18 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crawley, D.B.; Lawrie, L.K.; Winkelmann, F.C.; Buhl, W.; Huang, Y.; Pedersen, C.O.; Strand, R.K.; Liesen, R.J.; Fisher, D.E.; Witte, M.J.; et al. EnergyPlus: Creating a new-generation building energy simulation program. Energy Build. 2001, 33, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andarini, R. The Role of Building Thermal Simulation for Energy Efficient Building Design. Energy Procedia 2014, 47, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstić, H.; Teni, M. Review of Methods for Buildings Energy Performance Modelling. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 042049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, L.; Ruggeri, A.G. Developing a model for energy retrofit in large building portfolios: Energy assessment, optimization and uncertainty. Energy Build. 2019, 202, 109356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Yang, Y.; Sa, X.; Wei, X.; Zheng, H.; Shi, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Z. Evaluation of the Impact of Input-Data Resolution on Building-Energy Simulation Accuracy and Computational Load—A Case Study of a Low-Rise Office Building. Buildings 2023, 13, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejadshamsi, S.; Eicker, U.; Wang, C.; Bentahar, J. Data sources and approaches for building occupancy profiles at the urban scale—A review. Build. Environ. 2023, 238, 110375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillich, A.; Saber, E.M.; Mohareb, E. Limits and uncertainty for energy efficiency in the UK housing stock. Energy Policy 2019, 133, 110889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymath, A. What is a U-Value? Heat Loss, Thermal Mass and Online Calculators Explained [WWW Document]. NBS. 2015. Available online: https://www.thenbs.com/knowledge/what-is-a-u-value-heat-loss-thermal-mass-and-online-calculators-explained (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Yilmaz, S.; Prakash, N.; Firth, S.K.; Shimoda, Y. A cross analysis of existing methods for modelling household appliance use. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2018, 12, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Jin, M.; Spanos, C.J. Modeling of end-use energy profile: An appliance-data-driven stochastic approach. In Proceedings of the IECON 2014—40th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Dallas, TX, USA, 29 October–1 November 2014; pp. 5382–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candanedo, L.M.; Feldheim, V.; Deramaix, D. Data driven prediction models of energy use of appliances in a low-energy house. Energy Build. 2017, 140, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, H. (kth Royal Institute of Technology). Hybrid Model Approach to Appliance Load Dis-Aggregation: Expressive Appliance Modelling by Combining Convolutional Neural Networks and Hidden Semi MARKOV Models. Retrieved from Stockholm, Sweden. 2015. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:881880/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Yao, J. Modelling and simulating occupant behaviour on air conditioning in residential buildings. Energy Build. 2018, 175, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keyser, R.; Ionescu, C. Modelling and simulation of a lighting control system. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2010, 18, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priarone, A.; Silenzi, F.; Fossa, M. Modelling Heat Pumps with Variable EER and COP in EnergyPlus: A Case Study Applied to Ground Source and Heat Recovery Heat Pump Systems. Energies 2020, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, C.B.; Hoff, B.; Ostrem, T. Framework for Modeling and Simulation of Household Appliances. In Proceedings of the IECON 2018—44th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Washington, DC, USA, 21–23 October 2018; pp. 3472–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radatz, P.; Rocha, C.H.; Peppanen, J.; Rylander, M. Advances in OpenDSS smart inverter modelling for quasi-static time-series simulations. CIRED-Open Access Proc. J. 2020, 2020, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happle, G.; Fonseca, J.A.; Schlueter, A. A review on occupant behavior in urban building energy models. Energy Build. 2018, 174, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.; Whitacre, G.R.; Crisafulli, J.J.; Fischer, R.D.; Rutz, A.L.; Murray, J.G.; Holderbaum, S.G. TANK Computer Program User’s Manual with Diskettes: An Interactive Personal Computer Program to Aid in the Design and Analysis of Storage-Type Water Heaters; Battelle Memorial Institute: Columbus, OH, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, C.C.; Lowenstein, A.I.; Merriam, R.L. NO-94-11-3--Detailed Water Heating Simulation Model. In Proceedings of the 1994 Winter Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–30 June 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Little (Arthur D.), Inc. Engineering Computer Models for Refrigerators, Freezers, Furnaces, Water Heaters, Room and Central Air Conditioners; Little (Arthur D.), Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, J.; Grant, P.; Kloss, M. Simulation Models for Improved Water Heating Systems; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bünning, F.; Sangi, R.; Müller, D. A Modelica library for the agent-based control of building energy systems. Appl. Energy 2017, 193, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibabaei, N.; Fung, A.S.; Raahemifar, K. Development of Matlab-TRNSYS co-simulator for applying predictive strategy planning models on residential house HVAC system. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, T.P.; Emmerich, S.J.; Thornton, J.B.; Walton, G. Integration of Airflow and Energy Simulation Using CONTAM and TRNSYS. In American Society of Heating, Refregerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Symposium Papers; ASHRAE: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, M.J.; Dols, W.; Mathisen, H. Using Co-simulation between EnergyPlus and CONTAM to evaluate recirculation-based, demand-controlled ventilation strategies in an office building. Build. Environ. 2022, 211, 108737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojić, M.; Kostić, S. Application of COMIS software for ventilation study in a typical building in Serbia. Build. Environ. 2006, 41, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L. Vehicle HVAC System in Sim-Scape. MATLAB Central File Exchange. 2023. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/62811-vehicle-hvac-system-in-simscape (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Seyyed, A. Heat Exchanger Solver. 2021. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/46303-heat-exchanger-solver (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Franke, R.; Casella, F.; Sielemann, M.; Proelss, K.; Otter, M. Standardization of Thermo-Fluid Modeling in Modelica. Fluid. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/988180 (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Burhenne, S.; Wystrcil, D.; Elci, M.; Narmsara, S.; Herkel, S. Building Performance Simulation Using Modelica: Analysis of the Current State and Application Areas. In Proceedings of the 13th Conference of the International Building Performance Simulation Association, Chambery, France, 25–28 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hydronics Library. Available online: https://www.claytex.com/products/dymola/model-libraries/hydronics/ (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Til, Modelica Library for Simulation of Fluid Systems, Developed by TLK-Thermo GmbH and TU Braun-Schweig, Institut für Thermodynamik, 9/2009. Available online: https://2009.international.conference.modelica.org/proceedings/pages/exhibitors/TLK-Thermo/TLK_TIL.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Müller, D.; Lauster, M.; Constantin, A.; Fuchs, M.; Remmen, P. AixLib—An Open-Source Modelica Library within the IEA-EBC Annex 60 Framework. In Proceedings of the BauSIM 2016, Dresden, Germany, 14–16 September 2016; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bouquerel, M.; Ruben Deutz, K.; Charrier, B.; Duforestel, T.; Rousset, M.; Erich, B.; van Riessen, G.; Braun, T. Application of MyBEM, a BIM to BEM Platform, to a Building Renovation Concept with Solar Harvesting Technologies. In Proceedings of the Building Simulation Conference, Bruges, Belgium, 1–3 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Heat pumps Open Modelica. Available online: https://build.openmodelica.org/Documentation/Buildings.Fluid.HeatPumps.html (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- HeatingResistor Open Modelica. Available online: https://doc.modelica.org/om/Modelica.Electrical.Analog.Basic.HeatingResistor.html (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Version 4.0.0. Available online: https://build.openmodelica.org/Documentation/Buildings.UsersGuide.ReleaseNotes.Version_4_0_0.html (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Boiler. Available online: https://build.openmodelica.org/Documentation/BuildSysPro.Systems.HVAC.Production.Boiler.Boiler.html (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Eborn, J.; Tummescheit, H.; Pr¨olß, K. AirConditioning—A Modelica Library for Dynamic Simulation of AC Systems. In Proceedings of the 4th International Modelica Conference, Hamburg, Germany, 7–8 March 2005; Gerhard Schmitz, G., Ed.; pp. 185–192. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=377a2777cbea97cc0b1f566c7215457858595a81 (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- OpenEMS. Available online: https://github.com/OpenEMS/openems (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Open-Source IoT Platform. Available online: https://github.com/openremote/openremote (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Honda Smart Home Projec. Available online: https://www.hondasmarthome.com/tagged/hems (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- FlexiblePower Alliance Network. Available online: https://github.com/flexiblepower (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- openHAB. Available online: https://github.com/openhab (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Uddin, M.; Nadeem, T. EnergySniffer: Home Energy Monitoring System using Smart Phones. In Proceedings of the 2012 8th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Limassol, Cyprus, 27–31 August 2012; pp. 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]