4.1. Data Source and Sample Characteristics

The daily closing prices of Tesla, Inc., Austin, USA (ticker: TSLA) listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange were obtained from Yahoo Finance, covering the period from 3 January 2017 to 16 April 2025. This dataset comprises a total of 2084 trading days, spanning more than eight years of market activity, including periods of significant volatility in the electric vehicle sector and broader stock markets. Let denote the closing price on trading day t.

Based on these prices, daily arithmetic returns were computed as

and the corresponding daily log returns were calculated as

where the factor 100 converts the logarithmic returns to percentage terms. This computation yields 2083 daily log-return observations for empirical analysis. The log-return formulation is preferred in financial econometrics due to its desirable statistical properties, including time-additivity and approximate normality over short intervals, facilitating the modeling of returns and risk.

In this paper, we acknowledge that our current modeling approach assumes log returns are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.), which implies that returns at different time points are uncorrelated and drawn from the same marginal distribution. While this simplification facilitates flexible modeling of skewness, kurtosis, and tail behavior, it necessarily ignores well-documented temporal features in financial data, such as volatility clustering, autocorrelation, and regime-dependent dynamics.

In particular,

Kim (

2024) investigates the volatility clustering of trading-volume turnover ratios in Asia-Pacific stock exchanges using a GARCH framework and demonstrates that periods of high or low volatility tend to persist over time. This highlights that financial time series often exhibit conditional heteroskedasticity, which cannot be captured under the i.i.d. assumption. Consequently, ignoring such temporal dependence may affect both the estimation of tail-related risk measures and the modeling of extreme events.

We note that our current focus is on marginal distributions and tail characteristics; nevertheless, combining the proposed composite distribution framework with time-varying volatility models (e.g., GARCH-type specifications) represents a promising extension for future work. Such integration would allow more accurate estimation of tail risks, Value-at-Risk (VaR), Expected Shortfall (ES), and improved risk assessment during periods of market stress.

The dataset obtained from Yahoo Finance is publicly accessible and widely used in financial research, ensuring transparency and reproducibility. It should be noted that TSLA uniquely identifies Tesla, Inc. on the NASDAQ stock exchange, guaranteeing unambiguous retrieval of stock data in financial databases and avoiding potential confusion with other companies. Given these characteristics of the dataset and the observed statistical properties of TSLA returns, we further justify the selection of TSLA as the asset of analysis. Specifically, its high volatility, heavy-tailed return distribution, and sensitivity to macroeconomic, technological, and speculative factors make it an appropriate case for assessing the performance of the proposed skew-kurtotic distribution in capturing asymmetries and extreme returns. Furthermore, TSLA has experienced a variety of notable corporate events, such as stock splits, earnings announcements, and technological milestones, providing a rich empirical context to test model robustness under realistic market conditions. As our primary objective is to investigate extreme-return dynamics and tail risk rather than general market behavior, TSLA’s characteristics align well with the study’s goals, ensuring that the selection is guided by theoretical, empirical, and methodological considerations rather than convenience.

The chosen period from 2017 to 2025 includes structurally distinct economic and financial regimes: a pre-COVID global expansion phase, the severe market disruptions during 2020–2021 due to the pandemic, and a subsequent post-pandemic recovery phase characterized by volatility, inflation, monetary policy shifts, geopolitical tensions, and changing investment patterns. Returns during this period may exhibit outliers, structural breaks, and time-varying volatility. These features are recognized in the model design to ensure robust parameter estimation and reliable inference. Including years after 2022 further allows observation of long-term economic adjustments, supply chain reconfigurations, and the evolution of market dynamics, providing a comprehensive context for interpreting model results. Relevant external factors, such as oil and energy prices, benchmark interest rates, global inflation, and technological or regulatory changes, are also considered as they directly affect asset performance. Overall, this time span is chosen based on analytical, contextual, and methodological reasoning rather than mere data availability, enhancing the credibility, transparency, and empirical validity of the study.

The empirical analysis focuses on a single asset, Tesla (TSLA), primarily to demonstrate the application and performance of the proposed distribution model on a representative dataset exhibiting non-normal features. This choice is intended for methodological illustration and does not restrict the general applicability of the approach. The manuscript explicitly discusses avenues for future research to extend the empirical validation to additional stocks, indices, and other financial assets, thereby assessing robustness across different markets and asset classes.

For subsequent analysis, the daily log-return series of Tesla, Inc. will be denoted simply as TSLA. Preliminary descriptive statistics reveal that TSLA returns exhibit non-negligible skewness and excess kurtosis, consistent with typical characteristics of equity returns, such as asymmetry and fat tails, which justify the application of heavy-tailed and skewed distribution models in risk modeling and extreme value analysis.

To gain an initial understanding of the data characteristics, we first examine basic descriptive statistics for the daily log returns, as summarized in

Table 4.

As shown in

Table 4, the mean log return is 0.0051, indicating an overall upward trend in the stock price during the sample period. The standard deviation of 5.6163 reflects substantial volatility and a high level of investment risk. More strikingly, the log returns exhibit a skewness of −12.5991 and a kurtosis of 308.5935, deviating drastically from the normal distribution (which has skewness = 0 and kurtosis = 3). The large negative skewness indicates a pronounced left tail with extreme loss events, while the exceptionally high kurtosis signals a sharply peaked distribution with fat tails and numerous outliers.

These features confirm that the TSLA log returns are non-normal, heavily skewed, and leptokurtic. Consequently, traditional models based on normality may fail to capture the actual risk. More flexible distributions that accommodate skewness and heavy tails, such as the skew-normal and skew-t distributions, are therefore more appropriate.

In light of these empirical characteristics, the next step is to construct and evaluate a composite distribution model that can accurately capture the pronounced peaks, skewness, and heavy tails observed in the TSLA daily log returns. This approach allows for more realistic modeling of extreme events and tail behavior, which is crucial for risk management and financial analysis.

4.2. Parameter Estimation and Data Fitting

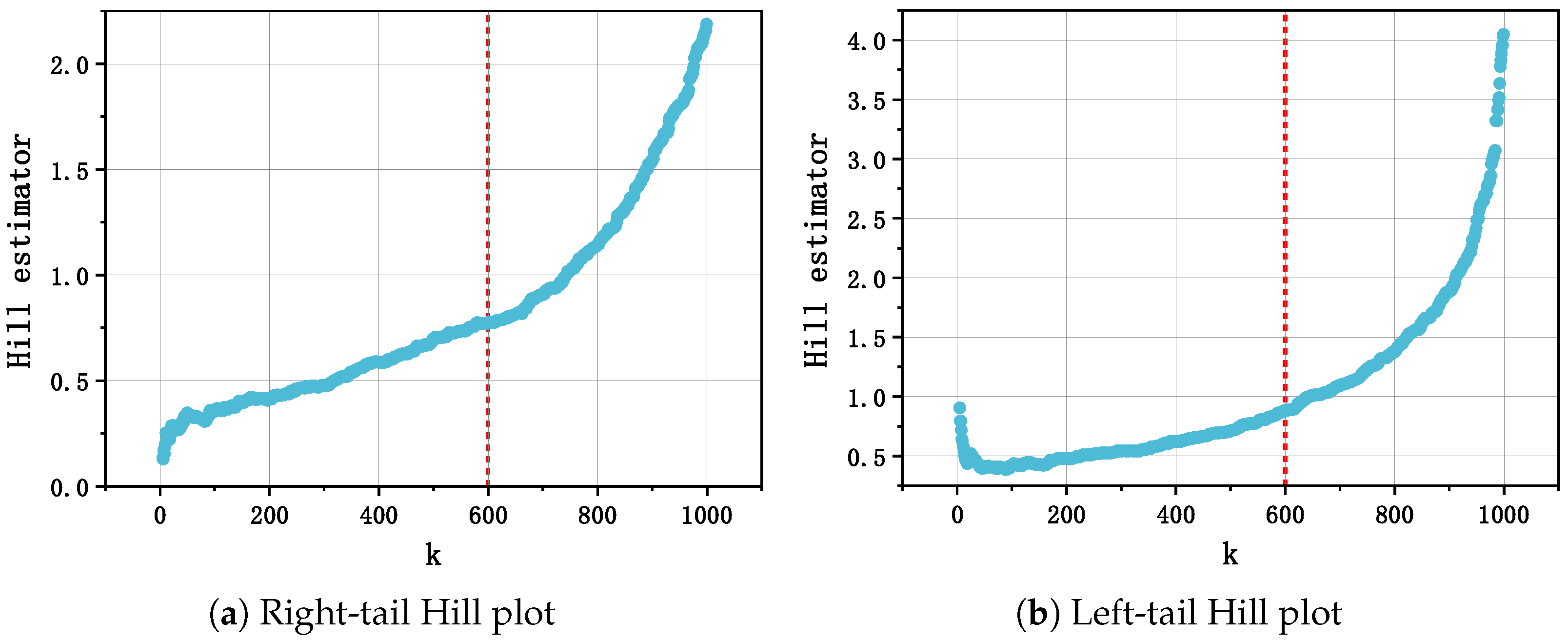

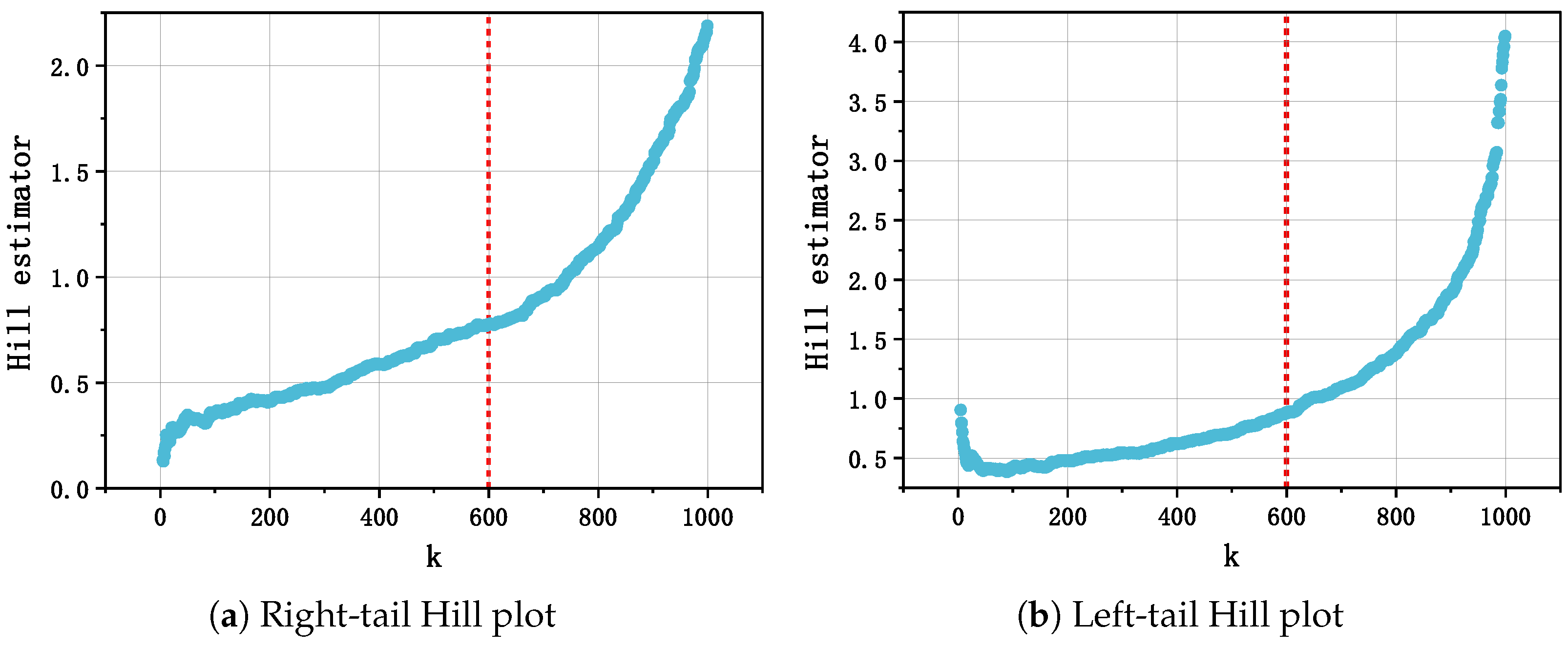

We begin by selecting thresholds for extreme-value analysis using Hill plots. A Hill plot displays the Hill estimator of the tail index across a range of threshold values and is widely used to assess tail heaviness and guide threshold selection. Empirical distributions often exhibit asymmetric behavior in the lower and upper tails, so we analyze the two tails separately. Specifically, we first construct a Hill plot for the left (lower) tail to identify a suitable threshold for negative extremes and then repeat the procedure for the right (upper) tail. This two-sided approach ensures that extreme events on both ends of the distribution are properly captured. By choosing tail-specific thresholds, we strike a balance between including sufficient extreme observations and achieving reliable tail estimation.

Based on the Hill plots (

Figure 3), we select the observation corresponding to

as the threshold separating the left and right tails. To justify the choice of

, we examine the Hill plots in detail to identify the so-called “stable region.” A stable region is defined as a range of

k values over which the estimated tail index

exhibits minimal fluctuation. Within this interval, the tail index estimates are relatively insensitive to the choice of

k, indicating that the threshold reliably captures the tail behavior. For both the left and right tails, visual inspection of the Hill plots shows that

remains approximately constant for

k values between roughly 550 and 650. The selected value

lies near the center of this stable region, ensuring a balance between including sufficient extreme observations and maintaining robust tail index estimation. This procedure provides a transparent and reproducible basis for threshold selection in the empirical analysis.

The resulting thresholds, and , partition the support of the random variable into three regions corresponding to the left tail, central body, and right tail. Observations in the central region are modeled using a skew-normal distribution , which extends the normal family to accommodate asymmetry. Observations in the tails, or , are modeled using a common skew-t distribution , allowing both skewness and heavy-tailed behavior with tail index controlled by the degree-of-freedom parameter . By construction, the same skew-t parameters govern both tails, reflecting a symmetric tail functional form while preserving heterogeneity relative to the central body.

For parameter estimation, we treat the previously determined thresholds

and

as fixed. Let

denote the observed sample, and define the following index sets corresponding to the three regions:

Using the notation

and their corresponding CDFs

and

, the composite PDF is given by

where the composite parameter vector is

and

are determined via the continuity constraints in Equation (

4) rather than being freely optimized.

4.2.1. Log-Likelihood Decomposition

The log-likelihood function for the observed data is

Since the data are partitioned into disjoint regions,

can be written as

where

,

, and

Because the same skew-

t parameters

govern both tails, we can aggregate the tail contributions:

where

and

.

4.2.2. Maximum Likelihood Estimation

The MLE is defined by

subject to the constraints

In practice, estimation proceeds by numerically optimizing the central-parameter block and the tail-parameter block separately:

Because the composite log-likelihood decomposes and each term involves disjoint subsets of the data, this approach yields stable estimation while respecting the design that the same skew-t parameters describe both tails.

4.2.3. Description of Tabled Statistics

Table 5 summarizes the estimation results for the composite, skew-normal, and skew-

t models. For clarity, the table includes the following key statistics:

Parameters: location (), scale (), shape (), and degrees of freedom () for skew-t and composite distributions. Thresholds and are fixed values separating left, central, and right regions.

LOGLIKE: maximized log-likelihood value for each fitted model, indicating overall goodness of fit.

AIC and BIC: Akaike and Bayesian information criteria, balancing model fit and complexity. Lower values indicate a better trade-off between fit and parsimony.

Left-Tail KS and Right-Tail KS: Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistics computed for the left and right tails, respectively. Smaller values indicate that the model better captures the tail behavior of the empirical distribution, which is particularly important in financial risk applications.

Table 5 reports the estimated parameters, maximized log-likelihoods, and information criteria (AIC and BIC) for the three fitted models. In terms of log-likelihood, both the skew-

t and composite distributions achieve comparable fits and are substantially better than the skew-normal distribution, indicating the importance of capturing heavy tails and skewness in financial return data. Specifically, the skew-normal distribution, with only three parameters, fails to adequately model tail thickness, resulting in a lower log-likelihood and correspondingly larger AIC and BIC values. The skew-

t distribution, by introducing the degree-of-freedom parameter, effectively captures tail heaviness, yielding the smallest AIC and BIC. The composite distribution, while achieving a similar log-likelihood to the skew-

t, includes more parameters (nine in total) to separately model the central body and tails, leading to slightly higher AIC and BIC values.

It should be emphasized that information criteria balance goodness of fit with model complexity. In the context of extreme risk modeling in finance, accurate tail fitting is often more critical than overall information criteria. The composite distribution allows precise control over tail behavior by separately modeling the central part and both tails while sharing a common skew-t tail parameter. As a result, it performs particularly well in tail KS tests and in simulations of extreme returns. Therefore, despite slightly higher AIC and BIC compared with the skew-t, the composite distribution provides substantial advantages for applications such as extreme risk measurement, Value-at-Risk, and Expected Shortfall estimation.

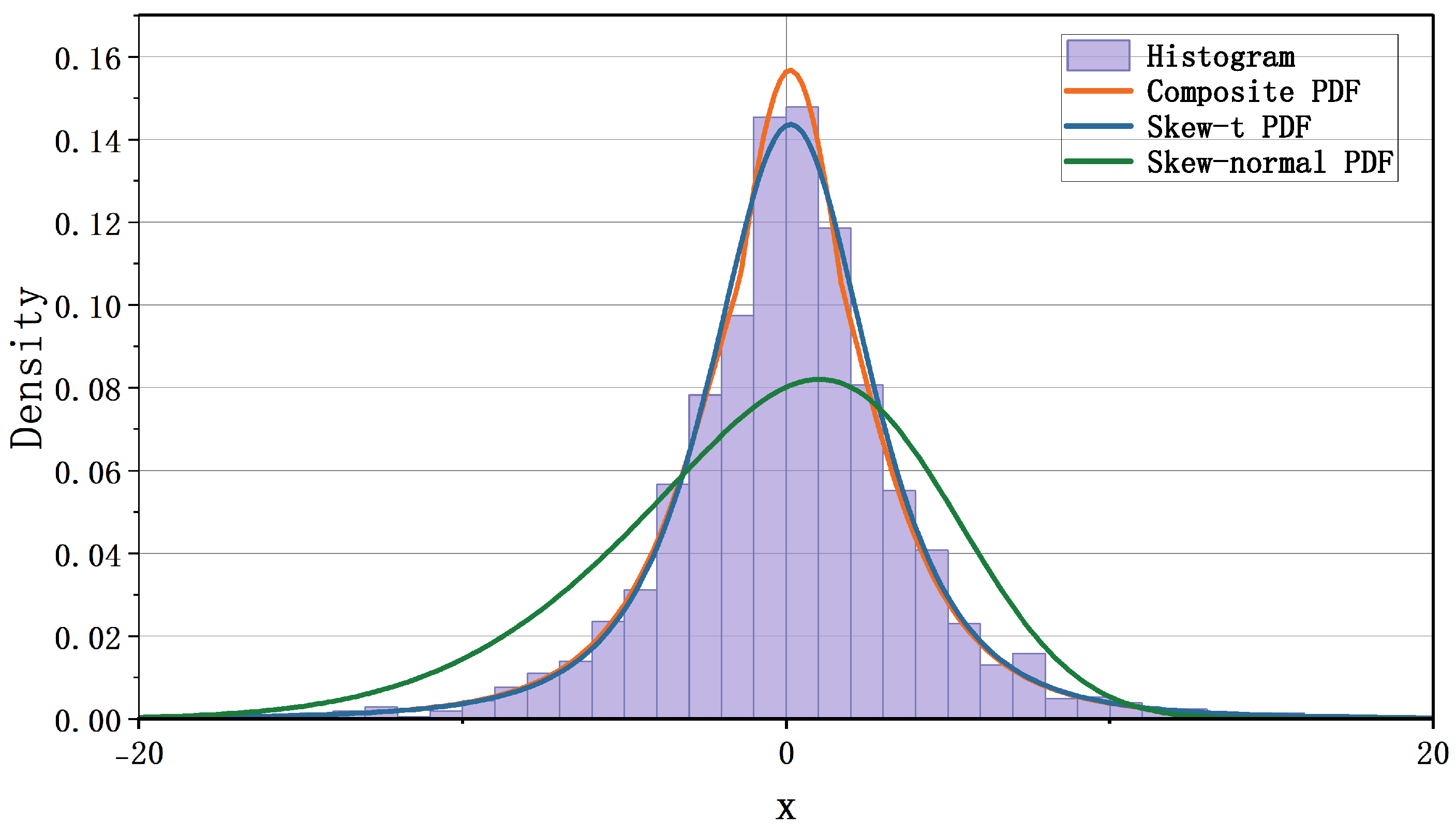

Figure 4 displays the fitted densities for the daily log returns of TSLA. Both the composite and the skew-

t distributions capture the heavy tails and asymmetry of the empirical return distribution, while the composite distribution shows a sharper central peak, indicating greater sensitivity to central-region variation. The skew-normal distribution yields a flatter central shape and fails to capture the extreme-return behavior as effectively. These qualitative observations are consistent with the log-likelihood values in

Table 5.

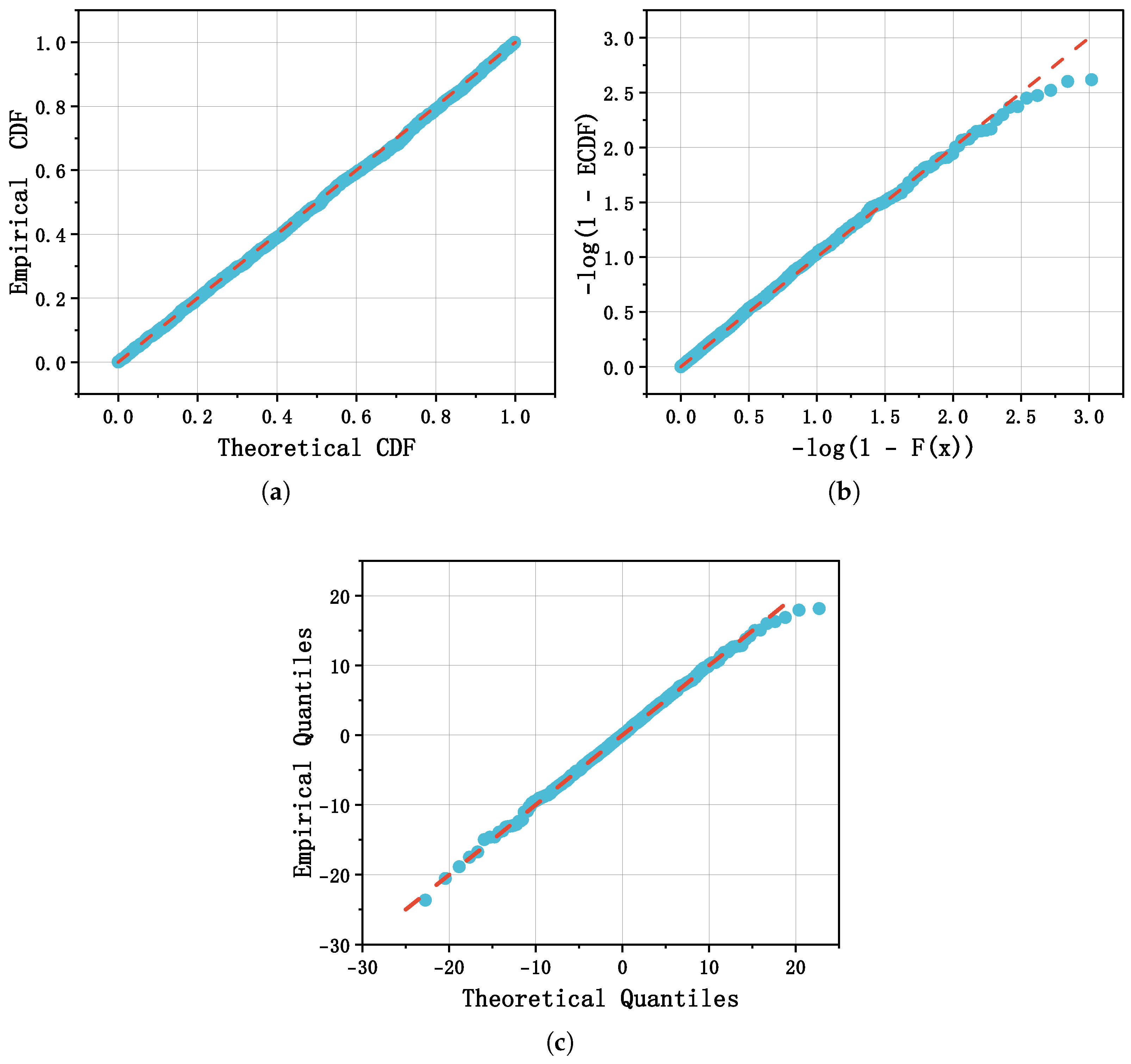

To further assess goodness of fit,

Figure 5 presents diagnostic plots for the composite distribution: (a) the probability–probability (P–P) plot, which compares the fitted CDF and ECDF; (b) the negative log P–P plot, obtained by applying a negative logarithmic transformation to the P–P coordinates so as to magnify small probability differences, thereby making discrepancies in the distribution tails more visible; and (c) the quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot, which compares fitted and empirical quantiles and provides additional insights into tail behavior. The P–P plot primarily evaluates the overall agreement between the fitted and empirical distributions across the support, whereas the Q–Q plot focuses on quantile alignment, with both tools complementing each other in highlighting goodness of fit.

As shown in

Figure 5a,c, most points in the P–P plot lie close to the reference lines, indicating good overall agreement between the fitted and empirical distributions. The Q–Q plot, however, shows a small number of outliers at both ends, particularly in the upper-right corner, highlighting remaining challenges in capturing extreme observations precisely. These deviations likely correspond to rare but significant events in financial markets, such as sudden crashes, liquidity shocks, or macroeconomic disturbances, rather than mere model inadequacy. Although limited in number, such extreme observations can disproportionately affect tail-dependent risk measures, including Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Expected Shortfall (ES), and are therefore important for stress testing and capital allocation. From a statistical perspective, these extreme values can influence likelihood-based estimation and tail-index inference, particularly in models with heavy-tailed or skewed components, underscoring the need for careful interpretation of tail-related results.

Figure 5b confirms that tail fit is reasonable: the upper-right region of the negative log P–P plot does not show large systematic departures, supporting the view that the skew-

t component adequately models tail behavior in our composite specification. A small number of points in this region still deviate slightly from the reference line, reflecting rare extreme observations that may correspond to sudden market events or other tail risks. These deviations, although limited in number, can have a disproportionate impact on tail-dependent measures, such as Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Expected Shortfall (ES), and thus warrant careful consideration in both risk assessment and statistical inference.